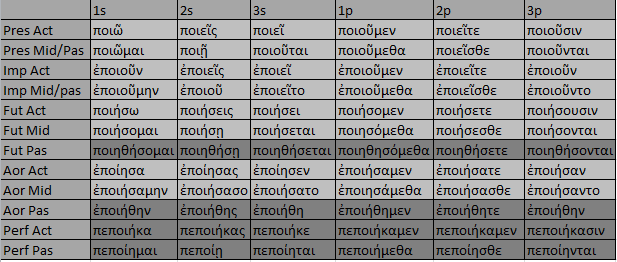

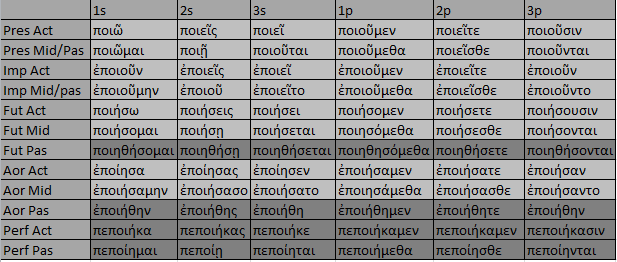

I am assuming that if a verb has the II Aor it has II everything else. Thanks a lot!

(The dark spots are things I'm fairly confident that I'm wrong about)

Totally agreed, I formed this paradigm after finishing Mounce's set of chapters on the indicative and memorizing the list of augments, conn. vowels, etc. for each tense.RandallButh wrote:Memorizing whole paradigms is not the road to fluency, although with fluency you will be able to generate the paradigm, at least as far as the language is internalized.

Both of these statements make sense to me. Writing these tables out really makes it easier to understand how the verb works, and helps you read. If you want to get fluent in Greek (something I'm still working on), then reading, writing, listening, and speaking are all important.Chris Servanti wrote:Totally agreed,RandallButh wrote:Memorizing whole paradigms is not the road to fluency, although with fluency you will be able to generate the paradigm, at least as far as the language is internalized.

!!! SNIP !!!

After spending an hour or two putting together that chart and then typing it, I understand how all the tenses relate WAY better.

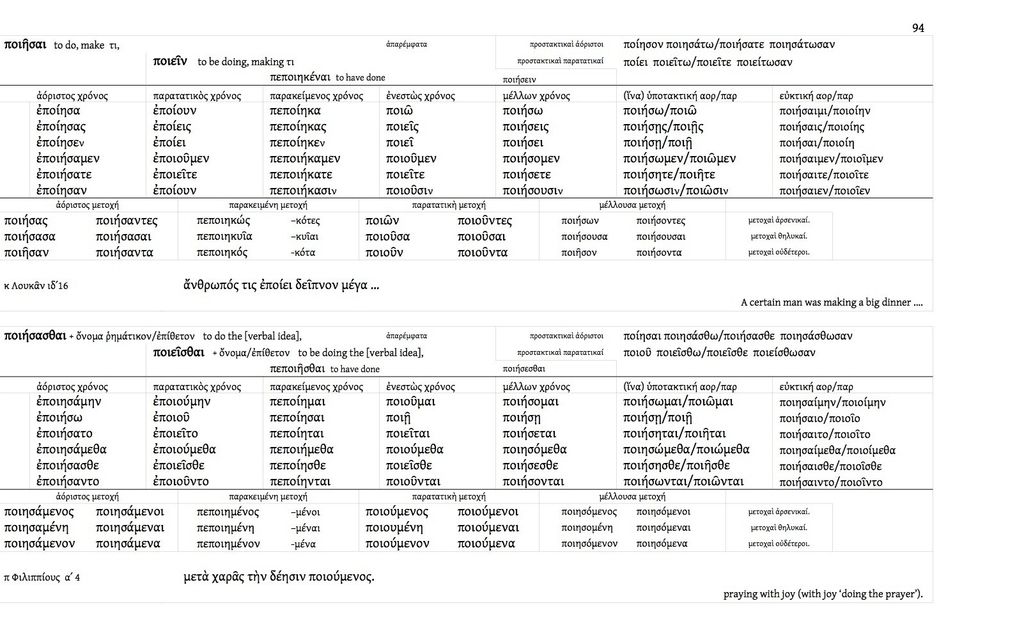

A very useful resource.RandallButh wrote:See the Greek Morphologia, available at http://www.biblicallanguagecenter.com. It has about two hundred of the most common verbs and patterns listed for you in complete tables for a particular voice of a particular verb (not limited to accidental occurrence of NT forms!), along with a helpful English to Greek index (including some necessary/common words not occurring in NT), and all the noun/adj patterns collected at the back.

Good advice.RandallButh wrote:How does one use such a table?

1. for reference one can check and see how the verb handles something or how it appears in a particular form. This is always useful for adult learners.

2. One can bite off a small piece of the paradigm and play with ONLY that piece. E.g. "I was doing, you were doing, he was doing." Use only that piece in multiple situations and communication. Let the accent pattern sink in deeply, with twenty different usages and examples. 3. Only then, if one wants, try connecting to another small piece. Like jumping from 'I was doing' to 'I am doing', again in appropriate contexts. Listen to the accent shifts. Memorizing whole paradigms is not the road to fluency, although with fluency you will be able to generate the paradigm, at least as far as the language is internalized.

Can you write the english names for these greek terms? My book only gives the English tense and aspect namesRandallButh wrote:I will try to paste a page from the morphologia book that has two tables, ποιεῖν to be doing (active) and ποιεῖσθαι to be doing (middle). I will try to paste from a PDF in order to preserve formatting. . . .

--that didn't work.

So I'm trying a JPG, though unsure of the resolution in the final result here:

Looks alot smaller, but maybe that's just my machine.

How does one use such a table?

1. for reference one can check and see how the verb handles something or how it appears in a particular form. This is always useful for adult learners.

2. One can bite off a small piece of the paradigm and play with ONLY that piece. E.g. "I was doing, you were doing, he was doing." Use only that piece in multiple situations and communication. Let the accent pattern sink in deeply, with twenty different usages and examples. 3. Only then, if one wants, try connecting to another small piece. Like jumping from 'I was doing' to 'I am doing', again in appropriate contexts. Listen to the accent shifts. Memorizing whole paradigms is not the road to fluency, although with fluency you will be able to generate the paradigm, at least as far as the language is internalized.

That is a problem.(Also, am I right in assuming that if a verb has the I Aor Act, it will also have I Aor Mid, I Aor Pas, etc.? Like ποιειν takes the I Aor Act form, so I assumed that means it should take the I Future Pas as well)