Tippoo breaks the treaty with the Peishwa – His great preparations – supposed by the English to be intended against them – Nana Furnuwees proposes a defensive alliance, which is declined by Lord Cornwallis – Transactions between the British authorities and Nizam Ally – Guntoor given up – Nizam Ally negociates with the English and with Tippoo – results Lord Cornwallis’s letter to Nizam Ally – Tippoo considers that letter tantamount to an offensive alliance against him – His unsuccessful attack on the lines of Travancore – Alliance of the English, the Peishwa, and Nizam Ally, against Tippoo – its terms – First campaign of the English in this war against Tippoo – Dilatory proceedings of the allies – A British detachment joins Pureshram Bhow – Mahrattas cross the Kistna – Moghuls advance to lay siege to Kopaul and Buhadur Benda – Mahrattas lay siege to Dharwar – operations – Dharwar capitulates after a protracted siege – Capitulation infringed – Lord Cornwallis assumes command of the British army – Capture of Bangalore – Mahratta army marches from Poona under Hurry Punt Phurkay – Sera surrendered – Mahratta armies advance to join the British and Moghuls before Seringapatam – Lord Cornwallis defeats Tippoo at Arikera, but is compelled to abandon his design of besieging Seringapatam – Distress of his army – relieved by the unexpected junction of the Mahrattas – Various operations – A party of Mahrattas surprised and cut off by Kummur-ud-deen – Lord Cornwallis reduces the forts between Bangalore and Gurumcondah – Moghuls unable to reduce Gurumcondah, leave a party to mask it, which is surprised – Pureshram Bhow’s scheme of reducing Bednore – Battle of Simoga – Admirable conduct of Captain Little – Simoga capitulates – Pureshram Bhow advances towards Bednore, but retires with precipitation – Operations at Seringapatam – Peace concluded with Tippoo – Cause of Pureshram Bhow’s retreat explained – The armies return to their respective territories – Distress of Pureshram Bhow’s army

At the period when Sindia retreated to Gwalior, we have observed, that one reason which prevented Nana Furnuwees from supporting him with troops from the Deccan proceeded from fresh aggressions on the part of Tippoo; in fact, the latter scarcely permitted Hurry Punt to re-cross the Kistna, when he retook Kittoor; and an army, assembled at Bednore, threatened a descent on the Mahratta territories in the Concan. As often happens with respect to the capricious conduct of the native princes of India, it is difficult to reconcile this procedure with the reasons which had so recently induced Tippoo to tender hasty proposals of peace. Some of the English, from the various rumours in circulation, concluded that it was a deception, contrived with the consent of Nana Furnuwees, preparatory to a general confederacy against the British; in which the Mahrattas, Nizam Ally, Tippoo, and the French, had become parties. In regard to the Mahrattas, there was no foundation for this supposition, but there was reason to believe that Tippoo had renewed his engagements with the French, and that his designs were more hostile to the British than to the Mahrattas; but he wished to conceal his real object until he could prepare his army and obtain effectual assistance from France. Nana Furnuwees believed that the invasion of the Mahratta territories was his chief object; and in the end of the year 1787, proposed to the governor-general, Lord Cornwallis, through Mr. Malet, to form, on the part of the Peishwa, a defensive alliance with the English, in order to control the

overbearing and ambitious spirit of Tippoo. Lord Cornwallis, though impressed with a belief of the great importance of this offer, as essential to the safety of British India, was prohibited by act of parliament from accepting it, until Tippoo should break through his engagements by some unequivocal act or declaration of hostility. In declining it therefore, he instructed Mr. Malet to offer general assurances of the sincere desire of the governor-general to cultivate the friendship of the Peishwa’s government.

The reports of Tippoo’s hostile intentions became less prevalent during the early part of 1788; and this apparent tranquillity afforded a favourable opportunity of carrying into effect the intentions of the governor-general respecting the district of Guntoor, which, by the treaty concluded with Nizam Ally in 1768, ought to have been ceded to the English upon the death of Busalut Jung in 1782. Captain Kennaway was the agent deputed for the purpose of obtaining its surrender; but the motive of his mission was kept secret until he could reach Hyderabad, and preparations be completed at Madras for supporting the demand. Soon after captain Kennaway’s departure from Calcutta, it was again confidently reported, that Tippoo was engaged in hostile machinations; that an attack made upon Tillicherry, by the Raja of Cherika, was at his instigation; and that he meditated the subjugation of the territories of the Raja of Travancore, the ally of the English, which formed an important preliminary to the conquest of the British settlements in the south of

India. Captain Kennaway, in consequence of these reports, was instructed, to confine his immediate communications to general expressions, of the great desire of the governor-general to maintain, the most amicable understanding with the Soobeh of the Deccan, in all affairs that might arise requiring adjustment. But soon after, as appearances bespoke no immediate hostility on the part of Tippoo, and Nizam Ally seemed disposed to settle everything with the British government in an equitable manner, the demand for Guntoor was made, and the district given over without impediment, and almost without hesitation, in September 1788. Notwithstanding his apparent readiness, Nizam Ally was greatly mortified at finding himself compelled to surrender Guntoor; but he was by this time sensible, that of the four great powers in India, his own was the weakest; and that without a steadfast alliance with some one Of the other three, his sovereignty must be swallowed up. The Mahrattas, from contiguity, and from their claims and peculiar policy, he most dreaded; personally, he was inclined to form an alliance with the Mahomedan ruler of Mysore; but some of his ministers, particularly Meer Abdool Kassim, in whom he had great confidence, strongly advised him to prefer a connection with the English, and endeavoured to show, by what means the late concession might be made instrumental in effecting the desired object. He proposed, that as the English had obtained possession of Guntoor, they should be called upon to fulfil those articles of the treaty of 1768, by which they had agreed to furnish the Hyderabad state,

with two battalions and six pieces of cannon; to reduce the territories of Tippoo, and to pay the Soobeh of the Deccan a certain annual tribute. Nizam Ally, acceding to these suggestions, despatched Meer Abdool. Kassim to Calcutta, for the purpose of obtaining the concurrence of the governor-general. With his habitual duplicity, however, Nizam Ally, at the same time, sent another envoy29 to Tippoo, proposing a strict and indissoluble union between the Mahomedan states; to which Tippoo declared his readiness to subscribe, on condition of an intermarriage in their families but the Moghul haughtily rejected such a connection, and the negotiation terminated.

When the envoy deputed to Calcutta submitted his proposals, the governor-general found himself under considerable embarrassment. No specific revision of the political relations between the English and Nizam Ally, had taken place since the treaty of 1768; but the treaty of Madras, between the English and Hyder in 1769, and that of Mangalore, with Tippoo in 1784, had each recognised both father and son, as lawful sovereigns of that territory; of which, by the treaty with Nizam Ally in 1768, Hyder was declared usurper; and of which the English had then arrogated to themselves the certainty of a speedy reduction. The governor-general was, as already mentioned, prohibited by act of parliament from entering on any new treaty, without express authority from the Court of Directors; but he was

particularly desirous of securing the alliance both of Nizam Ally and the Mahrattas, in consequence of his belief in Tippoo’s hostile proceedings, already commencing, by an attempt to subjugate Travancore, without appearing as a party in the aggression. The proposed affiance of the Mahrattas, Lord Cornwallis had been constrained to decline; but the danger which now more distinctly threatened, and the covert nature of Tippoo’s operations, which precluded proofs wholly sufficient for legal justification, induced Lord Cornwallis to adopt a line of conduct more objectionable than an avowed defensive alliance. In reply to Meer Abdool Kassim’s application, Lord Cornwallis explained the reason of his inability to perform that part of the treaty of 1768, which related to the conquest of the Carnatic Balaghaut; but by a letter which he now wrote to Nizam Ally, which letter he declared equally binding as a treaty, he promised that should the English, at any future period, obtain possession of the territory in question, they would then perform their engagements to him, and to the Mahrattas. This promise certainly implied, at least an eventual intention of subduing Tippoo, and that inference was strengthened, by an explanation of a part of the treaty, relative to the two battalions, which was before equivocal. Instead of being furnished with these battalions, as before expressed, when they could be spared, they were now to be sent, when required, and to be paid for, at the same rate as they cost the Company; merely on condition, that they were never to be employed against the allies of the British government. These

allies were at the same time expressly named; the Mahrattas were included, but Tippoo was omitted. Tippoo considered this letter as a treaty of offensive affiance against him. He was now at less pains to conceal his intended invasion of Travancore, and his unsuccessful attack on the lines, which he headed in person, was of course considered to be a declaration of war.

Nana Furnuwees no sooner heard of it, than he made specific proposals to the governor-general, through Mr. Malet, in name, both of his own master, and of Nizam Ally; which, with slight modifications, were accepted.

A preliminary agreement was settled on the 29th March, and a treaty, offensive and defensive, was concluded at Poona, on the 1st June, between Mr. Malet on the part of the Company, and Nana Furnuwees on the part both of the Peishwa and Nizam Ally; by which, these native powers stipulated that an army of 25,000 horse should attack Tippoo’s northern possessions, before and during the rains, and reduce as much as possible of his territory. That after the rains, they should act against Tippoo with their utmost means, and in case the governor-general should require the aid of 10,000 horse to co-operate with the English army, that number was also to be furnished within one month from the time of their being demanded, but maintained at the expence of the Company’s government. Both states were to be allowed two battalions, and their expence was to be defrayed by the Peishwa and Nizam Ally respectively, at the same rate as

they cost the Company. All conquests were to be equally shared, unless the English, by being first in the field, had reduced any part of the enemy’s territory before the allied forces entered on the campaign, in which case, the allies were to have no claim to any part of such acquisition. The Polygars and Zumeendars, formerly dependant on the Peishwa and Nizam Ally, or those who had been unjustly deprived of their lands by Hyder and Tippoo, were to be re-instated in their territory on paying a Nuzur, at the time of their re-establishment, which should be equally divided among the confederates, but afterwards, they were to be tributary to Nizam Ally and the Peishwa, respectively, It was also stipulated, that if after the conclusion of peace, Tippoo should attack any of the contracting parties, the others became bound to unite against him.

The treaty was not finally concluded by Nizam Ally until 4th July, as he hoped, by procrastination, to obtain the guarantee of the British government, not simply, as he pretended, to ensure protection to his territories from the Mahrattas during the absence of his troops on service, but to procure the interposition of the English in the settlement of the Mahratta claims, which even, where just, he had neither disposition nor ability to pay; and he foresaw that a day of reckoning was at no great distance. Lord Cornwallis, viewing the proposal simply as stated, could not accede to it without giving umbrage to the Mahrattas; but he assured Nizam Ally of his disposition to strengthen the connection between the two governments, when it

could be effected consistently with good faith, and a due regard to subsisting engagements, with other allies.

The first campaign of the English against Tippoo in this war, was conducted by General Medows. It commenced on the 26th May, 1790, and terminated by the return of the army to Madras on the 7th January 1791. The advantages obtained were by no means inconsiderable, but not so great as had been anticipated. General Medows, with the Madras army, invaded Tippoo’s territory from the south, and reduced Caroor, Dindigul, Coimbatoor, and Palghaut; whilst Colonel Hartley30, with a detachment of the Bombay army, assailed it from the west, gallantly attacked and routed a strong corps in the neighbourhood of Calicut, and a reinforcement being brought from Bombay by General Sir Robert Abercromby, who assumed the command, the province of Malabar was soon cleared of Tippoo’s troops31.

The Mahratta and Moghul armies had been declared ready to take the field, before the march of General Medows in May; but Nizam Ally, as we have seen, did not finally sign the treaty till July, and Pureshram Bhow Putwurdhun, the officer appointed to command the Mahratta army, did not receive his commission to raise and equip his troops until 5th May; on which day, he had his audience of leave from the Peishwa, and immediately set out for his own Jagheer

at Tasgaom, to make the necessary arrangements. The two battalions with their artillery32, which by the treaty the English had engaged to furnish, sailed from Bombay about the 20th May, disembarked on the 29th at Sungumeshwur, (the same place where Sumbhajee was made prisoner by the Moghuls upwards of a century before,) and ascended the Ambah Ghaut by the 10th June, although the natural difficulties of that stupendous pass were much increased by the setting in of the monsoon. On the 18th the detachment arrived at Koompta, a village within a few miles of Tasgaom, when the commander, Captain Little, found that not above two thousand horse had as yet assembled. Two carcoons had been sent to meet and accompany the British detachment on its march from the coast, and the many artificial delays and difficulties, raised by these Bramin conductors, to prolong the march, and conceal their want of preparation, were now explained. The dilatoriness of the Mahrattas appeared ambiguous to the English, especially as it was found, that Tippoo’s wukeels were still at Poona, where they were allowed to remain, as subsequently avowed by that court, in the vain hope, that Tippoo would endeavour to purchase their neutrality; for, although the Mahrattas had really no intention of breaking their engagements with the English, this mode of obtaining a supply of money from a tributary

who owed so much, was by them considered wholly justifiable. On the 5th of August, however, the wukeels were finally dismissed, but Pureshram Bhow did not cross the Kistna until the 11th; at which time, in addition to the British detachment, he had only five thousand horse, and about one-third of that number of infantry. In the course of a few days, he was joined by a body of horse, belonging to the Pritee Needhee; and a separate body of one thousand horse, whom it was at first proposed to attach exclusively to the British detachment, also joined, under a partizan officer named Dhondoo Punt Gokla, originally an agent superintending a part of the marine establishment at Viziadroog. His horse were not continued with the detachment as proposed; but the intention of thus employing them, was the commencement of a connection between Gokla’s family and the English; by whose influence, Bappoo Gokla, the nephew of Dhondoo Punt, was raised to high rank at the Peishwa’s court, where we shall ultimately see him, by no uncommon revolution, an active enemy of the British government.

Hostilities, on the part of the Mahrattas against Tippoo, commenced on the 25th August by an attack upon a fortified village, from which the Mahrattas expelled the garrison with trifling loss. As they advanced, the country was rapidly occupied. The inhabitants assisted to expel Tippoo’s Sebundees, but the latter were easily reconciled to a change of masters, enlisted with

Pureshram Bhow, and aided him in collecting the outstanding revenue. The Mahratta force, daily joined by small parties, soon amounted to ten thousand horse and three thousand infantry, exclusive of captain Little’s detachment. With this army Pureshram Bhow arrived before Dharwar on the 18th September, and after much unnecessary exposure, and considerable loss in reconnoitring, commenced the siege by firing cannon from a great distance during the day, and withdrawing them at night; an absurd practice not unusual with Mahrattas.

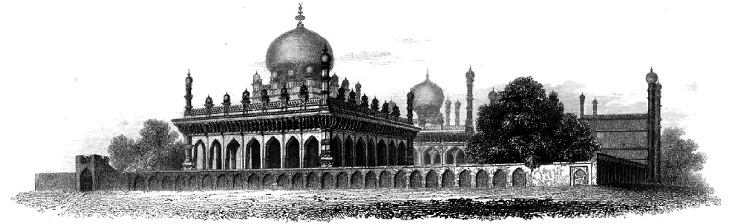

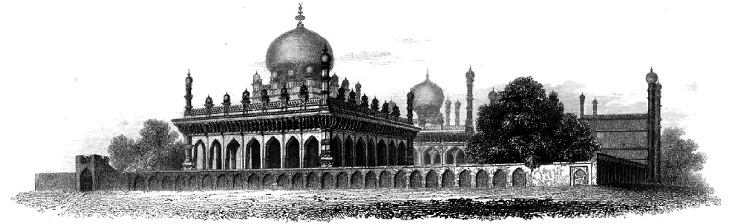

In the Carnatic, south of the Toongbuddra, Tippoo had stationed two officers, Budr-ul-Zeman Khan, and Kootub-ud-deen, at the head of about five thousand men, a few of whom were cavalry, but the greater part regular infantry. The Moghuls, as the Mahrattas were proceeding towards Dharwar, moved from Pangul to cross the Kistna in order to besiege Kopaul and Buhadur Benda; on which Kootub-ud-deen, with the whole of the horse and a part of the infantry, advanced to observe their motions, whilst Budr-ul-Zeman threw himself into Dharwar. The defences of this fortress are principally of mud, and though irregular, and now greatly decayed, were then very strong. It is situated in a, plain, having an outer and an inner ditch from twenty-five to thirty feet wide, and nearly as many feet deep. Adjoining to the fort, on the south side, and outflanking it to the eastward, is a town, or Pettah, defended by a low mud wall, and a ditch of no strength. The garrison, on

being reinforced, consisted of seven thousand regular and three thousand irregular infantry.

The first operation of any consequence, was an attack on a party of the enemy who had advanced outside of the town, but were driven back with the loss of three guns and a considerable proportion of killed and wounded, principally from the fire of the British troops. By their exertions also, the Pettah was stormed and taken; Captain Little the commander, and Lieutenant Forster were the first who mounted the wall, and both were wounded, the former severely, the latter mortally. This acquisition, which cost the British detachment sixty-two men, in killed and wounded, was made over to a body of Mahrattas, under Appa Sahib the son of Pureshram Bhow; but no sooner had the British returned to their camp, than the garrison sallied, and a very severe conflict ensued in the Pettah; five hundred Mahrattas were killed, and a still greater number of the garrison. Although the advantage was rather on the side of the Mahrattas, Appa Sahib withdrew his troops to camp, and permitted the garrison to re-occupy the town. After a truce, in order to allow each party to burn and bury their dead, the Mahrattas, who were ashamed again to call in the aid of the British detachment, attacked and retook the Pettah themselves.

The feeble and absurd operations, however, which generally distinguish Mahratta sieges, were never more conspicuous than on the present occasion. It must ever be a reflection upon those under whose orders the auxiliary force from Bombay was equipped, that there was

no efficient battering train to assist the operations of the Mahrattas: whose aid, if so supplied, might have contributed much more to the success of the war. In the first instance, it was excusable, because it might have been expected that the Mahrattas, if unprepared with battering cannon, would not employ themselves in sieges; but Captain Little had early represented, how necessary it became to send some heavy guns, ammunition and stores, not merely to save the credit of the British arms, but to ensure some useful co-operation on the part of their Mahratta allies. No battering train was sent, but a battalion of Europeans and another native corps were despatched under Lieutenant-colonel Frederick, who arrived in camp, before Dharwar, on the 28th December, and assumed command of the British force.

Every possible exertion was made by Colonel Frederick. Pureshram, Bhow’s artillery was manned by Europeans: but the guns were old, clumsy, and nearly unserviceable; so scanty was the supply of ammunition that they were frequently silent for days together, and the garrison, on these occasions, never failed to make a complete repair in the intended breach.

A considerable quantity of powder was at length obtained, but a prospect of its being again wholly expended, induced Colonel Frederick to attempt the assault before the breach, was, entirely practicable. He would probably have succeeded; but at the moment when the troops were to pass the ditch, the fascines, which they had, thrown into it, were set on fire, and so

rapidly consumed, that it became necessary to retire to the trenches. In this attempt the British detachment lost eighty-five men. The chagrin occasioned by failure, followed by a series of harassing delays, operating on an ardent mind and a debilitated constitution, proved fatal to Colonel Frederick, who died on the 13th March, and was succeeded in the command of the detachment by Major Sartorius. Materials were furnished so sparingly, that little impression was made by the batteries; but the Mahrattas carried on the approaches after their own manner, by running trenches and digging mines under the glacis. Frequent sallies, with various success, were made by the garrison; at length, after a protracted siege of twenty-nine weeks, a lodgement having been effected by the Mahrattas and the English, on the crest of the glacis, the brave veteran Budr-ul-Zeman Khan capitulated. The troops, with all the honours of war, were allowed to march out of the fortress, which was taken possession of by the confederates on the 4th of April. But the late garrison had only moved a short distance, when they were attacked by the Mahrattas, the greater part of them dispersed, and their commandant wounded, overpowered, and, with several others, made prisoner. It appears that Budr-ul-Zeman Khan had stipulated to surrender the fort, ammunition, and stores, in their actual condition, but the Mahrattas, having discovered that he had destroyed them after the capitulation was made, upbraided him with his want of faith; and accused

Hyder, Tippoo, and himself, of habitual violation of their engagements, particularly in regard to Gootee and Nurgoond. Their accusations were just; but Budr-ul-Zeman Khan, enraged at the insult, drew his sword, and his troops followed his example; the result of the fray proved as above related. Though the circumstances may induce us to believe that there was no premeditated treachery, the subsequent confinement of Budr-ul-Zeman Khan and several other prisoners, reflects discredit on the conduct of Pureshram Bhow33.

Before the fall of Dharwar, the British army had been some time in the field. Its first campaign against Tippoo in this war terminated, as we have already briefly mentioned, on the 27th January. On the 29th of the same month, Lord Cornwallis assumed the command of the army, and marched, on the 5th February, towards Vellore, where he concentrated his forces and advanced to Bangalore, which he invested on the 5th March, and carried it by assault on the night of the 21st of that month. This success tended to discourage the enemy, and stimulate the allies to exertion. The fall of Bangalore had some share in influencing the surrender of Dharwar, and also of Kopaul, besieged by the Moghuls, which was shortly afterwards given up, as was Buhadur Benda. The Moghuls, according to the treaty, were supported by two battalions of Madras native infantry, in the same manner as the Mahrattas were aided from Bombay. An army of

thirty thousand Mahrattas, of which 25,000 were horse, marched from Poona, on the 1st January, under the command of Hurry Punt Phurkay; advanced by Punderpoor and Sorapoor, forded the Kistna, where it is joined by the Beema and proceeded to Geddawal, whence Hurry Punt directed the main body of his army to continue its route to Kurnoul, whilst he proceeded to Paungul, with an escort of two thousand cavalry, for the purpose of conferring personally with Nizam Ally, whose court was then held at that frontier position, whence he affected to direct the operations of his field army. At this conference it was agreed, by Nizam Ally, and by Hurry Punt, on the part of his master the Peishwa, that they should abide by the terms of the treaty with the English, but only so far as might humble Tippoo, without absolutely annihilating his power. After the interview, Hurry Punt joined his army at Kurnoul,, where he remained some time, until hearing of the capture of Bangalore, he sent forward 10,000 horse with orders to endeavour to join Lord Cornwallis, in which he had been anticipated by the Moghuls; a body of that strength, having effected a junction with the English army on the 13th of April, after routing the party of Kootub-ud-deen, which we had occasion to mention, before the siege of Dharwar. But the Mahrattas, on arriving some days-afterwards at Anuntpoor, found that Lord Cornwallis had advanced towards Seringapatam. They therefore halted until joined by Hurry Punt with the main army, when the whole moved on to Sera.

It having occurred to the Mahratta commander to try the effect of summoning the place, Sera was most unexpectedly surrendered, and found full of stores and in high order. This success induced Hurry Punt to detach a party under Bulwunt Soob Rao, to besiege Mudgeery, situated twenty miles to the east of Sera; after which, leaving a strong garrison in his new acquisition, he proceeded to join the army at Seringapatam34. The other Mahratta army, acting on the north-western quarter of Tippoo’s territory, whose operations before Dharwar have been detailed, was now also advancing by orders from Hurry Punt towards Seringapatam. After the termination of the siege of Dharwar, a part of the British detachment was recalled to Bombay, and Captain Little, with three native battalions, the two with which/he entered on the campaign having been much weakened by casualties, continued with Pureshram Bow. The possession of Dharwar, and the forts taken by the Moghuls, gave the allies a strong hold on the country situated between the Kistna and Toongbuddra; Kooshgul, and several other places of less note, surrendered to Pureshram Bhow at the first summons; and the occupation of the country, with the consequent realization of revenue, became so inviting to the Mahratta general, that he soon evinced a greater care of his own interests, than those of the confederacy. It was recommended that he should join the Bombay army, under General Abercromby, then on its march from Malabar towards the capital of Mysore, through the territory

of a friendly chieftain, the Raja of Koorg. The Mahratta army, under Pureshram Bhow, had been greatly increased during the siege of Dharwar; he crossed the Toongbuddra on the 22d April, and arrived within twenty-four miles of Chittledroog, on the 29th of that month. Several fortified towns surrendered without resistance, and Mycondah was besieged by a detachment from his army; but when urged by Captain Little to advance in the direction by which General Abercromby was expected, or send on a part of his troops, he objected to it as unsafe, and continued his system of collecting from the surrounding country, until summoned by Hurry Punt to accompany him to Seringapatam35. Whilst Hurry Punt marched southwest, Pureshram Bhow moved south-east. Their armies were united at Nagmungulum, on the 24th of May, and on the ensuing day, they advanced to Mailgotta. But although thus near the capital; where they knew their allies were encamped, they had not been able to convey any intimation of their approach to Lord Cornwallis, as every letter was intercepted by the admirable activity of Tippoo’s mounted Beruds. This circumstance is considered very discreditable to Hurry Punt and Pureshram Bhow, by their own countrymen; and it was matter of most serious regret to Lord Cornwallis, that he had remained ignorant of their approach.

After the Moghul cavalry joined him, as already noticed, Lord Cornwallis resolved to undertake the siege of Seringapatam, and directed General

Abercromby to move forward from the westward, for the purpose of joining him at that capital. As the grand army advanced from the northward, Tippoo burnt the villages, destroyed the forage, and drove of both the inhabitants and their cattle, so that the space on which the army moved was a desert, and the condition of its cattle and horses soon proved the efficacy of this mode of defence.

On the 15th, Tippoo made a stand at Arikera, but was defeated; and, on the 19th, Lord Cornwallis encamped at Caniambaddy, to the west of Seringapatam. But the battle he had gained on the 15th, and his position at the gates of the capital, were advantages more than counterbalanced by the state of his cattle, and the alarming scarcity which prevailed in his camp. The want of forage and provisions, aggravated by the presence of the useless and wasteful Moghul horse, soon became so much felt, that combined with the lateness of the season, Lord Cornwallis abandoned all hope of being able to reduce Seringapatam before the monsoon; he therefore sent orders to General Abercromby to return to Malabar; destroyed his own battering guns and heavy stores, raised the siege, and on the 26th May, marched towards Mailgotta, from which place the Mahrattas had also moved that morning. Great was the surprise of the English army, when large bodies of horse were seen advancing, of whose approach they had no intimation. Conceiving them to be enemies, preparations were at first made to treat them as such; but their real character was soon discovered, and though not unclouded with

regret and disappointment, their arrival was hailed with great joy, as the ample supplies of the Mahratta Bazars afforded immediate relief to the famished camp. That we may not unjustly detract from the merit of the Mahratta commanders, as they have been accused of self-interested motives in the readiness with which they permitted their Bazar followers to sell to all comers: it is proper to mention, that though their followers took advantage of the period to raise the price of grain, their own troops suffered by the scarcity which for a few days ensued. Hurry Punt’s despatches evince a very humane and laudable anxiety to alleviate the distress of his allies. The junction of the Mahrattas near the spot where Trimbuck Rao Manna had gained the victory over Hyder, in 1771, was considered by them an omen particularly propitious.

The confederate armies remained for ten days in the neighbourhood of Seringapatam, in order to allow time for the convoys of grain, expected by the Mahrattas, to join the camp: after which, the whole moved to Nagmungulum. Hurry Punt proposed that they should proceed to Sera and take possession of the whole country between that place and the Kistna. Lord Cornwallis, however, considered it of prior importance to reduce the Baramahal and country in the neighbourhood of Bangalore, in order to facilitate the approach of the necessary supplies from Madras. Hurry Punt urged similar reasons in support of his own proposal, and was naturally seconded by the Moghuls; but as both depended on the English artillery and military stores, they yielded to the wishes of the governor-general. The army moved forward by

very slow marches, necessary to the English, from the exhausted state of their cattle, and the motions of the confederates were regulated accordingly. The fort of Oosoor was evacuated on the approach of the grand army. Pureshram Bhow, accompanied by Captain Little’s battalions, was detached towards Sera far the purpose of keeping open the northern communication, and overawing the country which had already submitted. Nidjigul surrendered to Pureshram Bhow, and the Killidar of Davaraydroog, promised to give it up, provided a part of the British detachment was sent to take possession; but on approaching the fort they were fired upon, and as Pureshram Bhow had not the means of reducing it, he burnt the Pettah in revenge, and proceeded to Sera. Being desirous of returning to the north-west, he assigned want of forage as a reason for hastily withdrawing to Chittledroog, where he surprised and cut off three hundred of its garrison, who happened to be outside and neglected to seek timely protection in the fort. Pureshram Bhow long indulged hopes of obtaining possession of this strong-hold by seducing the garrison; but all his attempts proved abortive; he however took several fortified places in its vicinity.

With regard to the operations of the other troops at a distance from the grand army, Bulwunt Soob Rao, the officer sent by Hurry Punt to besiege Mudgeery, did not succeed in gaining possession of it, but he left a detachment in the Pettah and went on to Makleedroog, Bhusmag, and Ruttengerry, of all which he took possession36. The

army of Nizam Ally, with the two Madras battalions which continued to the northward, took Gandicottah on the Pennar, and laid siege to Gurrumcondah.

The operations of Lord Cornwallis, after his retreat Seringapatam, until the season should admit of his renewing the siege, were chiefly in the Baramahal, the whole of which he reduced, except the strong hill-fort of Kistnagheery, which he intended to blockade, but previous to this arrangement one of Tippoo’s detachments, under Kummur-ud-deen, having surprised and cut off the party of Mahrattas left by Bulwunt Soob Rao at Mudgeery, the report of this circumstance was magnified into the total defeat and dispersion of Pureshram Bhow’s army, and induced Lord Cornwallis to proceed to Bangalore without forming the intended blockade. After hearing the true state of the case, he resolved on reducing the forts between Bangalore and Gurrumcondah, in the siege of which last the Moghul troops were still occupied. The whole tract soon fell; and amongst other places of strength the hill-fort of Nundidroog, when a part of the battering train used in its reduction was sent off to assist the Moghuls at Gurrumcondah, whither also most of their horse repaired.

By the beginning of December, Lord Cornwallis’s army had assembled at Bangalore, and might have advanced to Seringapatam, but the Bombay troops had a difficult march to perform before they could join; and Pureshram Bhow, though directed to be prepared to support their

advance, remained on pretence of sickness near Chittledroog. The Moghuls loitered with the camp at Gurrumcondah; and although Hurry Punt continued with Lord Cornwallis, the greater part of his troops were dispersed on various pretexts, but in reality, to occupy the districts, and to collect as much money as they could. As circumstances thus detained Lord Cornwallis from the main object of reducing the capital, he in the meantime laid siege to the forts in his route. Savendroog and Ootradroog were taken; Ramgheery, Shevingheery and Hooliordroog surrendered.

The Moghul army, after months spent before Gurrumcondah in a series of operations still more feeble than those of the Mahrattas before Dharwar, were at length put in possession of the lower fort by the exertions of Captain Read, the officer who had succeeded to the command of the English detachment37. The Moghuls having resigned all hope of reducing the upper fort, being anxious to join in the siege of Seringapatam, determined to mask it, and for that purpose, a considerable body of troops was left under Hafiz Fureed-u-deen Khan, a part of whom, under his personal command, he kept in the lower fort, and a small body was encamped at a little distance on the south side, under the orders of Azim Khan, the son of the Nabob of Kurnoul, and a Frenchman who had assumed the name of Smith. These arrangements being completed, the main body moved on with the intention of joining Lord Cornwallis, but they were speedily

recalled in consequence of an unexpected attack on the blockading party, many of whom were killed, and Hafiz Fureed-u-deen having been made prisoner, was basely murdered, from motives of revenge; he having been the envoy through whom the proffer of marriage on the part of Tippoo was sent, which was indignantly refused by Nizam Ally. The Frenchman Smith was also taken and put to death. On the return of the main body of the Moghuls, Tippoo’s troops, who were headed by his eldest son Futih Hyder, retired, and left the Moghuls to strengthen their party in the lower fort38. This arrangement being again completed, the Moghul army moved on, and joined Lord Cornwallis at Outradroog on the 25th January, 1792.

We have noticed the delay of the Mahratta commanders in collecting their detachments, and in engaging actively with the English, in the operations against the capital. The object of Hurry Punt was obviously plunder, but that of Pureshram Bhow extended to the long meditated Mahratta scheme of obtaining possession of the district of Bednore. Pureshram Bhow conceived that the present opportunity, whilst aided by a body of British troops at his absolute disposal, was too favourable to be omitted. Though fully informed by Lord Cornwallis of the general plan of operations, in which he was requested to co-operate, he no sooner saw the English army engaged in besieging the fortresses already mentioned, on its route towards Seringapatam, than he directed his

march straight towards Bednore.

Hooly Onore having been assaulted and taken by the British detachment, the Mahratta general continued his advance along the left bank of the Toong, intending to reduce the fort of Simoga. But at that place, besides the regular garrison, there was a force consisting of seven thousand infantry, eight hundred horse, and ten guns, under the command of Reza Sahib, one of Tippoo’s relations, who, on the approach of the Mahrattas, either from not deeming his position advantageous, or with a view to attack Pureshram Bhow when engaged in the siege, quitted his entrenchments close to the walls of the fort, and took post in a thick jungle a few miles to the south-west of it. His position was uncommonly strong, having the river Toong on his right, a steep hill covered with impenetrable underwood on his left, and his front protected and concealed, both by underwood and a deep ravine, full of tall and close bamboos, than which no trees form a stronger defence. One road only ran through this position, but it was more clear and open to the rear. Pureshram Bhow came in sight of the fort on the morning of the 29th December; but instead of attacking, made a considerable circuit to avoid it, and continued his route towards the position occupied by Reza Sahib.. Having arrived in its neighbourhood, the main army took up its ground of encampment; but Appa Sahib advanced towards the enemy with a body of cavalry. Pureshram Bhow requested of Captain Little to leave eight companies for the protection of the camp,

and move on with the rest of the battalions to support his son, which he immediately did. The closeness of the country rendered the attack of cavalry impracticable; and Captain Little’s three battalions, on this memorable occasion, mustered about eight hundred bayonets! Notwithstanding the comparative insignificance of his numbers, he did not hesitate in moving down on the enemy’s position: the irregular infantry of the Mahrattas following in his rear. Captain Little, for the purpose of ascertaining the manner in which the enemy was posted, and aware of the advantage of keeping his strength in reserve in such a situation, went forward with one battalion; and as the fire opened, he directed two companies to advance on the enemy’s right and two other companies to attack their left, whilst the rest were engaged with the centre. Every attempt to penetrate into the jungle was warmly opposed, but the enemy’s right seemed the point most assailable, though defended with obstinacy. Two companies were sent to reinforce the two engaged on the right; but Lieutenants Doolan and Bethune, who led them, were wounded successively. The grenadier company under Lieutenant Moor39 was sent to their support, that officer also fell disabled. Six companies of the 11th battalion were then brought forward, and Brigadier Major Ross, who directed them, was killed. The Sepoys repeatedly penetrated a short distance into the jungle; but most of their European officers being

wounded, they could not keep their ground. The Mahratta infantry, on every advance, rushed forward tumultuously, but were driven back in disorderly flight, which only added to the general slaughter, and contributed to the confusion of the regular infantry; but Captain Little, watching the opportunities when his men’s minds required support, with that admirable judgment and gallantry, which have, on so many occasions, distinguished the officers of British Sepoys, rallied, cheered, and reanimated them; sent on parts of the reserve, and continued the apparently unequal struggle with steady resolution. At last, the whole reserve was ordered up; the action continued with fresh spirit, and a small party got through the jungle into the enemy’s camp. Captain Little, who immediately perceived the importance of this advantage, skilfully prepared a strong body to support them. This reinforcement he headed in person, and arrived in time to secure the retreat of the small advanced party which had given way on their officer being wounded, and were completely overpowered and flying; rallying, however, at Captain Little’s word, and seeing themselves seconded, they turned on their pursuers with fresh energy. The enemy began to waver. The whole detachment was ordered to press forward. Captain Thomson, of the artillery, and the few European officers that remained, imitating the example of their gallant commander, led on with the greatest animation, drove the enemy from every point, and thus gained this well-fought battle. The Mahrattas rushed forward with their usual avidity to share the plunder, and

were useful in the pursuit, which Captain Little continued in the most persevering manner until he had taken every one of the guns, and rendered his victory as dispiriting and injurious to the enemy, as it was creditable and cheering to his own party.

The whole conduct of Captain Little, on this occasion, was most exemplary: it reminds us of the generalship of Lawrence, or of Clive, and of itself, entitles him to a very respectable rank in the military annals of British India. Of the small number of British troops engaged, sixty were killed and wounded, and the loss would have been much greater, but for the judicious conduct of their commander, who exposed them as little as possible until he knew where their strength could be exerted with effect. The Mahrattas, though they contributed but little to the success of the day, lost about five hundred men.

The fort of Simoga did not long hold out after the defeat of the covering army: it surrendered to Captain Little on the 2d January, and it was to him a very humiliating circumstance, that he was compelled to place the principal officers at the disposal of Pureshram Bhow, who, contrary to the terms of capitulation, detained them in the same manner as he had kept Budr-ul Zeman Khan.

Some time was spent in making arrangements for the occupation of the country about Simoga; but towards the middle of January, Pureshram Bhow, to complete his design, advanced through the woods in the direction of Bednore, which he reached on the 28th, and was preparing to invest

it, when, for reasons which will be hereafter explained, he suddenly retreated, and after returning to Simoga, took the straight route towards Seringapatam40. Lord Cornwallis, accompanied by Hurry Punt and the son of Nizam Ally, Sikundur Jah, arrived with the combined army before Tippoo’s capital on the 5th February. On the following day, the well-concerted and brilliant attack made by the English on his camp within the bound hedge, put the allies in possession of the whole of the outworks, and immediate preparations were made for commencing the siege. General Abercromby’s division joined on the 16th, and materially contributed to forward the operations, particularly by the gallant repulse of Tippoo’s attack on their advanced position on the 22d of February.

Tippoo repeatedly endeavoured to open negotiations; but his first overtures were for various reasons considered inadmissible; at last, in consequence of the more becoming form and tone of his proposals, together with the intercession of the allies, particularly of Hurry Punt, two wukeels, Gholam Ali and Ali Reza, were admitted to an audience on the 14th February, whilst in the mean time, the attack and defence were going forward as if no peace had been meditated. The wukeels were met by three agents, appointed by the allies respectively; Sir John Kennaway, on the part of Lord Cornwallis; Buchajee Rugonath, on that of Hurry Punt; and Meer Abdool Kassim, now distinguished by his title of Meer Alum, in behalf

of Sikundur Jah. After considerable discussion, and many references by the wukeels to their master, Tippoo, on the 23d February, the day after his unsuccessful attack on General Abercromby’s division, consented to cede half the territory which he possessed before the war; to pay three krores, and thirty thousand rupees, one half immediately, and the rest by three equal instalments within a year; to release all persons made prisoners from the time of Hyder Ally; and to deliver two of his sons as hostages for the due performance of the conditions. An armistice had taken place for two days, the hostages had already arrived in the English camp, upwards of one krore of rupees of the money had been paid, and the definitive treaty on the point of being concluded, when Tippoo, who appears to have at first overlooked the circumstance, finding that the principality of Koorg was included in the list of cessions, loudly remonstrated against yielding what he termed equivalent to the surrender of one of the gates of Seringapatam. Appearances indicated his determination to break the truce, but the prompt measures adopted by Lord Cornwallis for renewing the siege, and his declared resolution to give up none of the advantages already secured, induced Tippoo to reflect on the consequences, and finally to sign the treaty. Without reference to the condition of the former dependents of the Peishwa and Nizam Ally, or to that clause which secured a greater advantage to the party first in the field, the allies received an equal share of the districts ceded by Tippoo,

amounting annually to about forty lacks of rupees to each.

The share of the Mahrattas lay principally between the Wurdah and Kistna; it also included the valley of Sondoor near Bellary, which was still in possession of the Ghorepuray family. The portion allotted to Nizam Ally included (bootee and Kurpa, with the districts between the Kistna and Toongbuddra, of which Moodgul, Kannikgeeree and Kopaul, may be considered the western boundary, with the exception of a small district about Anagoondy, which Tippoo retained. Dindigul, Baramahal, Koorg and Malabar were assigned to the English.

We now return to explain the cause of Pureshram Bhow’s sudden retreat from Bednore, which was occasioned by his learning that Kummur-ud-deen had marched from Seringapatam with a strong force of infantry, for the purpose of entrapping him in the woods, and although success would have more than excused his proceedings at the Poona court, his failure, should he be afterwards hemmed in, would have ruined both himself and his army; for Nana Furnuwees, though he at first took little notice of the Bhow’s intention, no sooner found that it was generally understood, than he ordered him to desist, and proceed to Seringapatam. Lord Cornwallis, after he laid siege to that fortress, had pressingly written to Pureshram Bhow, describing the manner in which, he had invested it, and pointing out the essential service that might be rendered by his cavalry if posted on the south face of the

fortress; but Pureshram Bhow disregarded the application, until he received the information already mentioned. By the time, however, that he reached Seringapatam, the armistice was signed, and alp though Lord Cornwallis scarcely noticed his faithless conduct, it has been a theme of just censure; nor can Nana Furnuwees be exempted front a share of blame, for when urged by Mr. Malet to expedite the Bhow’s advance to the capital, he started difficulties as to the scarcity which his junction would occasion in the grand army, and would no doubt, have been well pleased to effect a conquest which had been a favourite object with his great master, the first Mahdoo Rao.

By the end of March, after the usual interchange of civilities, the commanders of the allied armies had put their troops in motion towards their respective frontiers. Hurry Punt returned by the eastern route to Poona, where he arrived on the 25th May; but Pureshram Bhow remained with the heavy baggage and stores, which together with his own artillery, and seventeen battering guns presented by Lord Cornwallis to the Peishwa, greatly retarded his progress. The devastation committed by his own troops on their advance rendered grain and forage extremely scarce, and the heat and drought of the season, together with the active annoyance which, notwithstanding the peace, he continued to experience from Tippoo’s Beruds and Pindharees, combined to render Pureshram Bhow’s march from Seringapatam to the Toongbuddra, one of the most distressing the Mahrattas ever experienced. Captain Little’s detachment

fortunately escaped the severe privations to which Pureshram Bhow’s army was subjected, by having been directed to join General Abercromby’s army, which marched to Malabar, and embarked at Cannanore for Bombay41.

29. His name was Hafiz Fureed-ud-deen Khan.

30. This is the same officer with whom the reader is already well acquainted.

31. Bombay and Bengal Records. Col. Wilks, &c.

32. The 8th and 11th battalions of native infantry, one company of European artillery, and two companies of gun Lascars, with six field pieces.

33. Narrative of Capt. Little’s detachment. Wilks, Moor, Bombay Records, Mahratta MSS. and Letters.

34. Hurry Punt’s despatches.

35. Mahratta MS. and Letters. Captain Little’s despatches, &c.

36. Hurry Punt’s despatches.

37. Bombay Records. Col. Wilks.

38. Letter from Lieut. Stewart, 1st assistant to the resident at Hyderabad.

39. Author of the interesting narrative of the operations of Captain Little’s detachment.

40. Moor, Wilks, Mahratta MSS. and letters.

41. Mahratta and English Records. Wilks, Moor, &c, &c.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()