Sivaji was born in May, 1627, and was thus eight years younger than his great adversary Aurangzib. He was brought up at his father’s jagir of Poona, where he was noted for his courage and shrewdness, while for craft and trickery he was reckoned a sharp son of the Devil, the Father of Fraud.’ He mixed with the wild highlanders of the neighbouring Ghats, and listening to their native ballads and tales of adventure, soon fell in love with their free and reckless mode of life. If he did not join them in their robber raids, at least he hunted through their country, and learnt every turn and path of the Ghats. He found that the hill forts were utterly neglected or miserably garrisoned by the Bijapur government, and he resolved upon seizing them, and inaugurating an era of brigandage on a heroic scale. He began by surprising the fort of Torna, some twenty miles from Poona, and after adding fortress to fortress at the expense of the Bijapur kingdom, without attracting much notice, crowned his iniquity in 1648 by making a convoy of royal treasure ‘bail up,’ and by occupying

the whole of the northern Konkan. A few years later he caused the governor of the more southern region of the Ghats to be assassinated, annexed the whole territory, captured the existing forts, and built new strongholds. Like Albuquerque, but with better reason, he posed as the protector of the Hindus against the Musalmans, whom he really hated with a righteous hatred; and his policy and his superstitious piety alike recommended him to the people, and, in spite of his heavy blackmail, secured their adhesion.

So far Sivaji had confined his depredations to the dominions of the King of Bijapur. The Mughal territory had been uniformly respected, and in 1649 the Maratha had shown his political sagacity, and prevented active retaliation on the part of the Adil Shah, by actually offering his services to Shah-Jahan, who had been pleased to appoint him to the rank of ‘a Mansabdar of 5000.’ The freebooter fell indeed under the temptation set before him by the war between Aurangzib and the Deccan Kings in 1656, and profited by the preoccupation of both sides to make a raid upon Junir. But Aurangzib’s successes soon convinced him that he had made a false move, and he hastened to offer his apologies, which were accepted. Aurangzib was then marching north to secure his crown, and could not pause to chastise a ridiculously insignificant marauder.

During the years of civil war and ensuing reorganization in Hindustan, Sivaji made the best of his opportunities. The young king Sikandar, who had

lately succeeded to the throne of Bijapur, in vain sought to quell the audacious rebel. An expedition sent against him about 1658 was doomed to ignominious failure, and its commander met a treacherous fate. Sivaji knew better than to meet a powerful army in the field; he understood the precise point where courage must give place to cunning, and in dealing with a Muslim foe he had no scruples of honour. When Afzal Khan advanced to the forts and forests of the Ghats at the head of a strong force, the Maratha hastened to humble himself and tender his profuse apologies, and the better to show his submissive spirit he begged for a private audience, man to man, with the general. The story is typical of the method by which the Marathas acquired their extraordinary ascendency. Afzal Khan, completely deluded by Sivaji’s protestations, and mollified by his presents, consented to the interview. Sure of his enemy’s good faith, he went unarmed to the rendezvous below the Maratha fortress, and leaving his attendants a long bowshot behind, advanced to meet the suppliant. Sivaji was seen descending from the fort, alone, cringing and crouching in abject fear. Every few steps he paused and quavered forth a trembling confession of his offences against the King his lord. The frightened creature dared not come near till Afzal Khan had sent his palankin bearers to a distance, and stood quite solitary in the forest clearing. The soldier had no fear of the puny quaking figure that came weeping to his feet. He raised him up, and was

about to embrace him round the shoulder in the friendly oriental way, when he was suddenly clutched with fingers of steel. The Maratha’s hands were armed with ‘tiger’s claws’ – steel nails as sharp as razors – and his embrace was as deadly as the Scottish ‘Maiden’s.’ Afzal died without a groan. Then the Maratha trumpet sounded the attack, and from every rock and tree armed ruffians fell upon the Bijapuris, who were awaiting the return of their general in care-. less security. There was no time to think of fighting, it was a case of sauve qui peut. They found they had to deal with a lenient foe, however. Sivaji had gained his object, and he never indulged in useless bloodshed. He offered quarter, and gained the subdued troopers over to his own standard. It was enough for him to have secured all the baggage, stores, treasure, horses, and elephants of the enemy, without slaking an unprofitable thirst for blood.

Once more the forces of Bijapur came out to crush him, and again they retreated in confusion. After this the Deccan sovereign left him unmolested to gather fresh recruits, build new forts, and plunder as he pleased. His brigandage was colossal, but it was conducted under strict rules. He seized caravans and convoys and appropriated their treasure, but he permitted no sacrilege to mosques and no dishonouring of women. If a Koran were taken, he gave it reverently to some Muhammadan. If women were captured, he protected them till they were ransomed. There was nothing of the libertine or brute about Sivaji. In the

appropriation of booty, however, he was inexorable. Common goods belonged to the finder, but treasure, gold, silver, gems, and satins, must be surrendered untouched to the State60.

Sivaji’s rule now extended on the sea coast from Kaliani in the north to the neighbourhood of Portuguese Goa, a distance of over 250 miles; east of the Ghats it reached from Poona down to Mirich on the Kistna; and its breadth in some parts was as much as 200 miles. It was not a vast dominion, but it supported an army of over 50,000 men, and it had been built up with incredible patience and daring. Like the tiger of his own highland forests, Sivaji had crouched and waited until the moment came for the deadly spring. He owed his success as much to feline cunning as to boldness in attack.

He was freed from anxiety on the score of his eastern neighbour the King of Bijapur, whose lands he had plundered at his will, and he now longed for fresh fields of rapine. The Hindus had become his friends, or bought his favour, and offered few occasions for pillage. He therefore turned to the Mughal territory to the north. Hitherto he had been careful to avoid giving offence to his adopted suzerain, but now he felt himself strong enough to risk a quarrel. His irrepressible thirst for plunder found ample exercise in the Mughal districts, and though he deprecated an assault upon the capital, lest he should provoke the Emperor to a war of extermination, he pushed

his raids almost to the gates of the ‘Throne-City,’ Aurangabad, which was now the metropolis of the Mughal power in the Deccan. Aurangzib’s uncle, Shayista Khan, then Viceroy of the Deccan, was ordered to put a stop to these disturbances, and accordingly proceeded, in 1660, to occupy the Maratha country. He found that the task of putting down the robbers was not so easy as it looked, even with the best troops in India at his back. Every fort had to be reduced by siege, and the defence was heroic. A typical instance may be read in Khafi Khan’s description of the attack on the stronghold of Chakna, one of Sivaji’s chief forts:–

‘Then the royal armies marched to the fort of Chakna, and after examining its bastions and walls, they opened trenches, erected batteries, threw up intrenchments round their own position, and began to drive mines under the fort. Thus having invested the place, they used their best efforts to reduce it. The rains in that country last nearly five months, so that people cannot put their heads out of their houses. The heavy masses cf clouds change day into night, so that lamps are often needed, for without them one man cannot see another man of a party. But for all the muskets were rendered useless, the powder spoilt, and the bows bereft of their strings, the siege was vigorously pressed, and the walls of the fortress were breached by the fire of the guns. The garrison were hard pressed and troubled, but on dark nights they sallied forth into the trenches and fought with surprising boldness. Sometimes the forces of the freebooter on the outside combined with those inside in making a simultaneous attack in broad daylight, and placed the trenches in great danger. After the siege had lasted fifty or

sixty days, a bastion which had been mined was blown up, and stones, bricks, and men flew into the air like pigeons. The brave soldiers of Islam, trusting in God, and placing their shields before them, rushed to the assault and fought with great determination. But the infidels had thrown up a barrier of earth inside the fortress, and had made intrenchments and plans of defence in many parts. All the day passed in fighting, and many of the assailants were killed. But the brave warriors disdained to retreat, and passed the night without food or rest amid the ruins and the blood. As soon as the bun rose, they renewed their attacks, and after putting many of the garrison to the sword, by dint of great exertion and determination they carried the place. The survivors of the garrison retired into the citadel. In this assault 300 of the royal army were slain, besides sappers and others engaged in the work of the siege. Six or seven hundred horse and foot were wounded by stones and bullets, arrows and swords.’

Eventually the citadel surrendered, and Chakna was rechristened ‘Islamabad’: but assaults and sieges like this cost more than the conquest was worth. Even when the Mughals seemed to have brought the northern part of the Maratha country under control, and Sivaji had buried himself in the hills, a fresh outrage dispelled the illusion. Shayista Khan was carousing one night in fancied security in his winter quarters at Poona. Suddenly the sounds of slaughter broke upon the ears of the midnight banqueters, who were regaling themselves after the day’s fast, for it was the month of Ramazan. The Marathas were butchering Shayista’s household. They got into the guardhouse, and killed every one they found on his

pillow, crying, ‘This is how they keep watch!’ Then they beat the Mughal drums so that nobody could hear his own voice. Shayista’s son was killed in the scuffle, and the general himself was dragged away by some of his faithful slave girls, and with difficulty escaped by a window.

This happened in 1663, after the Mughal army had been occupied for three years in subduing the robbers. The prospect was not encouraging, and to make matters worse the Mughal general laid the blame of the midnight surprise upon the treachery of his Rajput colleague Jaswant Singh. The Raja had played the traitor before: he had tried to desert to Shuja on the eve of the most decisive battle in Bengal; he had pledged himself to Dara, and then thrown the unfortunate Prince over for Aurangzib; and he was suspected of being peculiarly susceptible to monetary arguments. Nothing, however, was proved against him in the Poona affair, and Aurangzib found his military science and his gallant following of Rajputs too valuable to be lightly discarded. Accordingly, Shayista was recalled and transferred to Bengal61, and Prince Mu’azzam, the Emperor’s second son, was appointed to the command in the Deccan, with the Raja Jaswant Singh as his colleague. Sivaji celebrated the occasion by sacking Surat for (Fryer says) forty days (Jan.–Feb. 1664): Sir George Oxindon indeed repulsed him from the English factory with much credit, but he carried off a splendid booty from the

city. Nothing more outrageous in the eyes of a good Muslim could be conceived than this insult to Surat, the ‘Gate of the Pilgrimage,’ until the sacrilege was eclipsed by the fleet which Sivaji fitted out at forts which he had built on the coast, for the express purpose of intercepting Mughal ships, many of which were full of pilgrims on their way to or from the Holy City of Mecca. It seemed as though there were no limits to the audacity of this upstart robber, who, now that his father was dead, presumed to style himself Raja, low caste Maratha though he was, and to coin money as an independent sovereign.

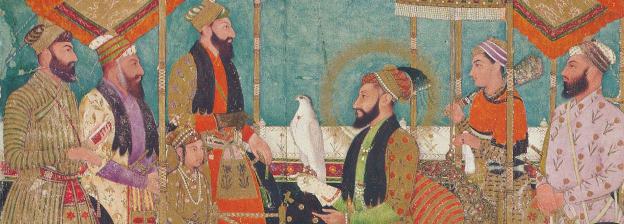

A fresh change of generals was tried. Jaswant Singh’s previous record justified the suspicion that he had turned a blind eye to the doings of his fellow Hindus, the violators of Surat. He was superseded, and Raja Jai Singh and Dilir Khan were appointed joint-commanders in the Deccan. Aurangzib never trusted one man to act alone; a colleague was always sent as a check upon him; and the divided command generally produced vacillating half-hearted action. In the present instance, however, Jai Singh and his colleague appear to have displayed commendable energy. Five months they spent in taking forts and devastating the country, and at length Sivaji, driven to earth, opened negotiations with Jai Singh, which ended in an extraordinary sensation: the Maratha chief not only agreed to surrender the majority of his strongholds, and to become once more the vassal of the Emperor, but actually went to Delhi and appeared

in person at the Court of the Great Mogul, to do homage to his suzerain for no less a feof than the Viceroyalty of the Deccan. No more amazing apparition than. this sturdy little ‘mountain rat ‘ among the stately grandeur of a gorgeous Court could be imagined.

The visit was not a success. Aurangzib clearly did not understand the man he had to deal with, and showed a curious lack of political sagacity in his reception of the Maratha. No prince or general in all India could render the Emperor such aid in his designs against the Deccan kingdoms as the rude highlander who had at last come to his feet. A good many points might well be stretched to secure so valuable an ally. But Aurangzib was a bigot, and inclined to be fastidious in some things. He could not forget that Sivaji was a fanatical Hindu, and a vulgar brigand to boot. He set himself the task of showing the Maratha his real place, and, far from recognizing him as Viceroy of the Deccan, let him stand unnoticed among third rank officers in the splendid assembly that daily gathered before the throne in the great Hall of Audience62. Deeply

affronted, the little Maratha, pale and sick with shame and fury, quitted the presence without taking ceremonious leave. Instead of securing an important ally, Aurangzib had made an implacable enemy.

He soon realized his mistake when Sivaji, after escaping, concealed in a hamper, from the guards who watched his house, resumed his old sway in the Ghats at the close of 1666, nine months after he had set forth on his unlucky visit to Court. He found that the Mughals had almost abandoned the forts in the Ghats, in order to prosecute a fruitless siege of Bijapur, and he immediately re-occupied all his old posts of vantage. No punishment followed upon this act of defiance, for Jaswant Singh, the friend of Hindus and affable pocketer of bribes, once more commanded in the Deccan, and the result of his mediation was a fresh treaty, by which Sivaji was acknowledged as a Raja, and permitted to enjoy a large amount of territory together with a new jagir in Reran The kings of Bijapur and Golkonda hastened to follow the amicable lead of the Mughal, and purchased their immunity from the Marathas by paying an annual tribute. Deprived of the excitements of war and brigandage, Sivaji fixed his capital in the lofty crag of Rahiri,

afterwards Raigarh, due east of Jinjara, and devoted himself to the consolidation of his dominion. His army was admirably organized and officered; and the men were highly paid, not by feudal chiefs, but by the government, while all treasure trove in their raids had to be surrendered to the State. His civil officials were educated Brahmans, since the Marathas were illiterate. Economy in the army and government, and justice and honesty in the local administration, characterized the strict and able rule of this remarkable man.

Aurangzib’s brief attempt at conciliation – if indeed it were such – was soon exchanged for open hostility. He had, perhaps, employed Jaswant Singh in the hope of again luring Sivaji into his power; in any case the plot had failed. Henceforth he recognized the deadly enemy he had made by his impolitic hauteur at Delhi. The Maratha, for his part, was nothing loth to resume his old depredations. He recovered most of his old forts, sacked Surat a second time in 1671, sent his nimble horsemen on raids into Khandesh, even defeated a Mughal army in the open field, brought all the southern Konkan – except the ports and territory held by the English, Portuguese, and Abyssinians – under his sway, and began to levy the famous Maratha chauth or blackmail, amounting to one-fourth of the revenue of each place, as the price of immunity from brigandage. He even carried his ravages as far north as Baroch, where the Marathas set an ominous precedent by crossing the Narbada

(1675). Then he turned to his father’s old jagir in the south, which extended as far as Tanjore, and was now held for the King of Bijapur by Sivaji’s younger brother. After forming an alliance with the King of Golkonda, who was jealous of the predominance of Bijapur; and after visiting him at the head of 30,000 horsemen and 40,000 foot, Sivaji marched south to conquer the outlying possessions of the common enemy, and to bring his brother to a sense of fraternal duty. He passed close to Madras in 1677, captured Jinji (600 miles from the Konkan) and Vellor and Arni, and took possession of all his father’s estates, though he afterwards shared the revenue with his brother. On his return to the Ghats, after an absence of eighteen months, he compelled the Mughals to raise the siege of Bijapur, in return for large cessions on the part of the besieged government. Just as he was meditating still greater aggrandizement, a sudden illness put an end to his extraordinary career in 1680, when he was not quite fifty-three years of age. The date of his death is found in the words Kafir be-jahannam raft, ‘The Infidel went to Hell63.’

‘Though the son of a powerful chief, he had begun life as a daring and artful captain of banditti, had ripened into a skilful general and an able statesman, and left a character which has never since been equalled or approached by any of his countrymen. The distracted state of the neighbouring

countries presented openings by which an inferior leader might have profited; but it required a genius like his to avail himself as he did of the mistakes of Aurangzib, by kindling a zeal for religion, and, through that, a national spirit among the Marathas. It was by these feelings that his government was upheld after it had passed into feeble hands, and was kept together, in spite of numerous internal disorders, until it had established its supremacy over the greater part of India. Though a predatory war, such as lie conducted, must necessarily inflict extensive misery, his enemies bear witness to his anxiety to mitigate the evils of it by humane regulations, which were strictly enforced. His devotion latterly degenerated into extravagances of superstition and austerity, but seems never to have obscured his talents or soured his temper64.’

‘Sivaji always strove to maintain the honour of the people in his territories,’ says a Muhammadan historian. ‘He persisted in rebellion, plundering caravans, and troubling mankind. But he was absolutely guiltless of baser sins, and was scrupulous of the honour of women and children of the Muslims when they fell into his hands.’ Aurangzib himself admitted that his foe was ‘a great captain’; and added ‘My armies have been employed against him for nineteen years, and nevertheless his State has been always increasing.’

60. Khafi Khan, l. c., vol. vii. pp. 260–1.

61. See p. 117. He died in Bengal in 1694, aged 93.

62. There is some mystery about this interview. Khafi Khan says, with little probability, that Aurangzib was not aware of the lavish promises which had been made to Sivaji in his name by Jai Singh. Bernier and Fryer explain Aurangzib’s coldness by the clamour of the women, who, like Shayista’s wife, had lost their sons by the bands of the Marathas. The risk of assassination by the injured relatives of his victims may well have given Sivaji a motive for escape from Delhi, but the vengeful appeals of the women could not have dictated Aurangzib’s policy. He never budged an inch from his set purpose to gratify a woman’s wish. The rumour that he connived at Sivaji’s escape, as mentioned by Fryer, in order to make a friend of the man whose life he thus saved, is improbable. Aurangzib certainly believed that he had more to gain by Sivaji’s death than by his friendship, which he despised; and subsequent events showed that the Maratha did not consider himself at all beholden to the Emperor for his safety.

63. Khafi Khan is proud to be the discoverer of this chronogram. It is, of course, to be interpreted by the numerical values of the consonants: K 20, Alif 1, F 80, R 200, B 2, J 3, H 5, N N 5o, 5o, R 200, F 80, T 400= 1091 A.H. (1680).

64. Elphinstone, History of India, 5th ed. (1866), p. 647.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()