In the year 1644 there was a great commotion in the palace of the Great Mughul at Agra. The clothes of a favourite daughter of the reigning emperor, Shah Jahan, had caught fire, and the princess had been severely burnt before the flames could be extinguished. In vain did native physicians of great learning and celebrity employ their skill and devote their time to effect a cure. To soothe the anxiety of the sorrowing father, some courtiers reminded him of the reputation which certain settlers from a distant country, carrying on their trade at Surat, had acquired for proficiency in the healing art. Catching at the idea, Shah Jahan despatched forthwith a messenger to the town on the Tapti, bearing a request that the foreign settlers would place at his disposal one of their most skilful practitioners.

The settlers hastened to respond, and deputed Mr. Gabriel Boughton, surgeon of the East India Company’s ship Hopewell, to attend the bidding of the ruler of India.

Mr. Boughton reached Agra, and succeeded in completely curing the princess. Asked to name his own reward, the patriotic Englishman allowed the opportunity of enriching himself to pass, and preferred to the Emperor the request that he would issue a firman granting permission to the English to trade in Bengal free of all duties, and to establish factories in the province. The firman was granted, and Mr. Boughton, taking it with him, set off at once to Rajmahal, where the Viceroy of Bengal, Sultan Shuja, second son of the Emperor, held his court.

Seven years before the event just recorded, the Surat merchants had obtained a firman which permitted them to trade in Bengal, but which restricted them to the port of Pipli, in the province of Orisa. The trade to this port had been opened, but the results had been so unsatisfactory that in 1643–4 the question whether the establishment at Pipli should be maintained or broken up was under the serious consideration of the Court of Directors.

The question was still pending when Mr. Boughton arrived with the revivifying firman at Rajmahal. His good fortune accompanied him to that place also. One of the royal ladies of the zenana of Sultan Shuja was lying ill; in the opinion of the native physicians hopelessly ill. Boughton cured her. Thenceforth the gratitude of the prince was unbounded. It displayed itself during the twelve years that followed in the assistance afforded to the Englishman in carrying out his scheme for establishing the trade in Bengal on an efficient and a permanent basis. Under his protection factories were established at Hugh, and agencies at Patna and Kasimbazar, and a little later at Dhakah and Baleshwar (Balasore).

The privilege of free trade throughout the provinces of Bengal

and Orisa was likewise granted for the annual nominal payment of Rs. 8,000.

The violent changes which occurred in the native dynasties during the forty years that followed did not practically affect the position thus secured to the English. But in the beginning of the year 1689, in consequence of the tyrannical conduct of Nuwab Shaista Khan, governor of the province for the Emperor Aurangzib, the Company’s Agent-in-Chief, Mr. Job Charnock, quitted Hugli with his subordinates, and sailed for Madras. Fortunately for English interests, Shaista Khan was succeeded during the same year by Ibrahim Khan. This man, known to our countrymen of that period as “the famously just and good Nuwab,” invited the English to return. Mr. Charnock complied (July 1690), but instead of proceeding to his old quarters at Hugh, he established the English factory at the village of Chatanati, north of the then existing town of Calcutta,7 twenty-seven miles nearer to the sea than the station he abandoned. Mr. Charnock survived the removal only eighteen months.

At this time the English settlers had no permission to fortify Chatanati, and their military establishment consisted of only 100 men. A rebellion against the Nuwab which broke out in Bengal in 1695 under the leadership of Subah Singh, a Hindu zamindar of Bardhwan, forced them to solicit, and enabled them to obtain, permission to defend themselves. They proceeded at once to erect walls of masonry, with bastions or flanking towers at the angles, round their factory. The bastions were made

capable of bearing guns, but in order not to excite the suspicion of the Nimbi), the embrasures were built up on the exterior with a facing of wall, one brick thick. This was the origin of the old fort, also called Fort William. It covered the site of the localities now known as Fairlie Place, the Custom House, and Koilah Ghat Street. Before the walls had been quite completed an attack was made upon it by the insurgents, who had set fire to the villages in the neighbourhood, but they were repulsed.8

On account of the rebellion, Ibrahim Khan was removed by the Emperor, who, after a short interval, sent his grandson, Prince ‘Azim u’sh Shan, to govern the province. From this prince, by means of a present of Rs. 16,000, the English obtained a grant of the three villages of Chatanati, Gobindpur, and Calcutta, with the lands adjacent to their fortified factory. As the wall of fortification occupied a portion of the ground appertaining to the village of Calcutta, that name was, for the first time, applied to the whole settlement (1699). The Company by this cession came to occupy the position of a zamindar, possessing administrative powers within the limits of the grant, and paying a yearly rental to the over-lord. In consequence of these acquisitions the Bengal settlement was raised to the rank of a Presidency, with a governor or, more correctly, a president in council, independent of Madras. The council of the new president was to consist of five members, inclusive of himself.9

In 1699 a new English company made a settlement at Hugli, in rivalry with the old company. The seven years which followed were principally marked by negotiations between the servants of the two companies. These terminated in 1706–7 by their fusion under the title of the United Company of Merchants of England trading to the East Indies. Hugli was

abandoned, and the strength of the United Company was concentrated within the limits of the three villages I have mentioned. Thenceforth, and for the ten years which followed, the contention was between the English settlers and the native lords of Bengal, the former persistently striving to extend free commercial intercourse with Bengal and to strengthen their fortifications, the latter constantly endeavouring to exact larger revenues from the English zamindars.

A circumstance, not dissimilar to that which had procured for the English the permission to establish factories and to trade freely in Bengal, came about this time to improve their fortunes and to extend their influence in the province. In 1713, the President of the Council despatched to the Court of Dihli an embassy composed of two European gentlemen, an Armenian interpreter, and a surgeon. The name of the surgeon was William Hamilton.

When the embassy reached Dihli, Farrakhsiyar, great grandson of Aurangzib, had but recently, by the defeat at Agra of his uncle, Jahandar Shah, obtained the throne of the Mughul. This prince had been suffering for some time from a complaint which had baffled all the skill of his physicians, and which compelled him to defer a marriage upon which he had set his heart, with a Hindu princess of Rajputana. Hamilton cured him. To show his gratitude, the Emperor, after the manner of Shah Jahan, requested him to name his reward. Hamilton, as patriotic and as careless of self-interest as Boughton, asked that the privileges granted to his countrymen in Bengal might be extended, and that they might be relieved from the exactions and oppressions of the Governor of Bengal. The Emperor promised to comply, and, after some delay, issued (1717)10 a firman confirming all previous grants to the English company, authorising them to issue papers which, bearing the signature of the President of the Council, should exempt the goods

named therein from examination or duty, and bestowing upon them the grant of thirty-eight villages about and below Calcutta on both sides of the river, on payment of an annual ground-rent. He likewise placed the use of the mint at Murshidabad at their disposal.

These privileges and this grant greatly increased the prosperity of Calcutta. For the ten years that followed its progress was enormous. Its trade rapidly developed, the shipping belonging to the port increased to 10,000 tons, and, what was of very great importance, the town attracted the wealthy natives of Bengal. These, by degrees, built houses in and near to it, and brought the influence of their wealth to sustain and increase its prosperity. It should be added that the firm rule of the Nuwab of the province, Murshid Kuli Khan, contributed not a little to this result. Originally opposed to the new favours extended to the English settlers, especially to that portion of them which would have given them the command of both sides of the river, he had forced them to agree to a compromise which, whilst it did not interfere with their trade, prevented them from obtaining a position dangerous to the interests of the Mughul. He likewise insisted that the free passes should neither be transferable nor used for the purposes of inland trade, but should be strictly confined to the goods of the Company intended for export. These trade rules were insisted upon, not only by Murshid Kuli Khan, but by his son-in-law, Shuja u’d din Khan, who succeeded him on his death in 1725, and who administered the province for the fourteen years that followed. The firm hand of the Nuwab, and the strict compliance with his reasonable regulations on the part of the settlers, combined throughout this period to augment the influence and increase the wealth of the Company.

Shuja u’d din Khan was succeeded in Bengal in 1739 by his son, Sarfaraz Khan, a debauchee. During his incumbency there occurred that terrible invasion of Nadir Shah, which

gave the most fatal blow to the stability of the rule of the Mughul. The subversive feeling, the result of this catastrophe, extended even to Bengal. Ali Vardi Khan, who had risen from the position of menial servant to the Nuwab of that province to be Deputy-Governor of Bihar, rose in revolt. The despotic conduct of Sarfaraz Khan had alienated the wealthy and respectable classes of the province. The great mercantile family of the Baths, the Rothschilds of Bengal, favoured the rebel.

His very generals betrayed him. When he marched to crush Ali Vardi Khan with a force vastly superior, they arranged that the guns should be loaded with powder only. The consequences were such as might have been expected. When the decisive battle ensued at Gheriah in January 1741, Sarfaraz Khan was slain, and his nobles and soldiers at once saluted Ali Vardi Khan as Nuwab of the three provinces of Bengal, Bihar, and Orisa.

The blow dealt by Nadir Shah at Dihli had so crushed the power of the Mughul that this revolution passed unnoticed. Ali Vardi Khan transmitted a handsome offering in money to the Emperor, Muhammad Shah, and was confirmed as Nuwab of Bengal, Bihar, and Orisa, just as any other adventurer who might have supplanted him, and have forwarded a like sum of money, would have been equally confirmed. It was, in fact, the recognition of force – the same recognition which was claimed, and fairly claimed, by the people who afterwards, also by force, supplanted the successor of Ali Vardi Khan. This prince ruled the three provinces for fifteen years, from 1741 to 1756. His reign was a continued struggle. He had scarcely succeeded to the position gained on the field of Gheriah when he was called upon to make head against a Maratha invasion. This invasion was the prelude to many others. They occurred every year from 1742 to 1750. They brought with them terror, desolation, often despair. Ali Vardi Khan resisted the invaders gallantly, and defeated them often. But

in the end their numbers and their pertinacity wore him out; and when, in 1750, they had mastered a great portion of Orisa he was glad to conclude with them a treaty whereby he yielded to them Katak, and agreed to pay a yearly tribute of twelve lakhs of rupees for Bengal and Bihar.

These invasions had not, however, interfered with the rising prosperity of the English settlement. Its security, in fact, invited more wealthy natives to take up their permanent abode within its bounds. Ali Vardi Khan, whilst continuing the privileges granted by his predecessors, had merely called upon the English, as he called upon all the zamindars of Bengal, to contribute to the expenses of the defence of the province. But such was their prosperity, that in one instance, when the Nuwab was hard pressed, they had paid him without difficulty three lakhs of rupees. Not but that the alarm caused by the Maratha invasion did not reach even Calcutta. But the English, prescient in their policy, took advantage of the universal feeling to ask for permission to dig a ditch and throw up an intrenchment round their settlement. The permission was accorded and the work was begun; but when three miles of it had been completed, and there were no signs of the approach of the Marathas, its further progress was discontinued. The work, some traces of which still remain, gave a permanent name to the locality, and to this day the slang term “the ditch” is often used to express the commercial capital of Bengal. Permission was granted at the same time .to erect a wall of masonry, with bastions at the corners, round the agency at Kasimbazar.

From the peace with the Marathas to 1756 nothing occurred to disturb the tranquillity of the English. On the 9th of April of that year, however, their protector, Nuwab Ali Vardi Khan died, and was succeeded by his favourite grandson, Siraju’d daulah.

This prince, who has been painted by historians in the blackest

colours, was not worse than the majority of Eastern princes born in the purple. He was rather weak than vicious, unstable rather than tyrannical, had been petted and spoilt by his grandfather, had had but little education, and was still a minor. Without experience and without stability of character, suddenly called upon to administer the fairest provinces of India and to assume irresponsible power, what wonder that he should have inaugurated his accession by acts of folly?

Surrounded from his earliest youth by flatterers, he had been encouraged to imbibe a hatred towards the foreign settlers on the coast. Their rising prosperity and their wealth, increased largely by rumour, excited, there can be no doubt, the cupidity of these brainless flatterers, and these, in their turn, worked on the facile nature of the boy-ruler.

The result was that Siraju’d daulah determined to inaugurate his reign by the despoiling of the English settlers. Charging them with increasing their fortifications and with harbouring political offenders, he seized their factory at Kasimbazar, imprisoned the garrison, and plundered the property found there (4th June 1756). Five days later he began his march towards Calcutta with an army 50,000 strong, attacked that place on the 15th, and obtained possession of it on the 19th June.

I would willingly draw a veil over the horrors of the Black Hole. That terrible catastrophe was due, however, not to a love of cruelty on the part of Siraju’d daulah, but to the system which inspired the servants of an absolute ruler with a fetish-like awe for their master. There can be, I think, no doubt that the Nuwab did not desire the death of his English prisoners. Mr. Holwell himself acquits him of any such intention, and attributes the choice of the Black Hole as the place of confinement to the of the subordinates.11 As to the

catastrophe itself, its cause was the refusal of the subordinates to awaken the Nuwab. That refusal might have been caused either by fear or by ill-will; but it was their refusal, not the refusal of the chief who was actually asleep. Thus much, but no more, may, in bare justice, be urged on behalf of Siraju’d daulah. For his conduct after the catastrophe not a word can be said. It is not upon record that he resented it. Most certainly those about him made him believe that the action had been planned with the best motives to draw from the English a confession as to the place where their wealth and treasures were hidden. His first act when he saw Mr. Holwell was to insist upon such confession being made. He expressed no regret, he extended to the captives no compassion, he spoke only of hidden treasures and their place of concealment. By his conduct he placed himself in the position of an accessory after the act.

The political result of the capture of Calcutta was the uprooting of the English settlements in Bengal. Of those who formed the garrison of Calcutta, some had been killed, others had been removed as prisoners to Murshidabad,12 the remainder had taken refuge on board the English vessels which were waiting, at Falta, the arrival from Madras of the troops who should avenge their wrongs and restore the fallen fortunes of the Company.

The news of the surrender of Kasimbazar reached Madras on the 15th July. Five days later a detachment of 280 European troops, commanded by Major Kilpatrick of the Company’s service, sailed from Madras. They reached Falta on the 2nd August. On the 5th of that month only did the story of the capture of Calcutta and its attendant consequences reach Fort St. George. Although the forces at the disposal of the Coast

Presidency were not more than sufficient to meet the attack from the French which was believed inevitable – France and England being on the brink of a rupture – it was resolved, after some hesitation, to despatch with all convenient haste a fleet and army to restore British fortunes in Bengal. The discussions leading to this conclusion, and afterwards those relating to the choice of a commander, caused very great delay, and it was not till the 16th October that the fleet conveying the little army sailed. The first ship reached Feta on the 11th December. All the others, two only excepted, arrived on or before the 20th. Of the two exceptions, one, the Marlborough, laden with stores, was so slow that she reached Calcutta only towards the end of January; the other, the Cumberland, grounding off Point Palmyras, was compelled to bear away to Vishakpatanam (Vizagapatam), and reached the river Hugli in the second week of March.

The commander of the military force was Robert Clive. The victory gained by this officer at Kaveripak had produced the most decisive results. It had enabled the English to relieve Trichinapalli, to force the surrender of the entire French army, to bestow the Nuwabship of the Karnatak upon their own nominee: in fine, it had caused the transfer of the predominance in Southern India south of the river Krishna from the French to our countrymen. In January 1753, Clive put the seal to his victories by the capture of the fortresses of Kovilam and Chengalpatt. In the following month he sailed for England. There he was received and feted as a hero. Of the same age as Bonaparte when Bonaparte made the marvellous campaign of 1796, he had acquired for his country advantages not less solid than those which the great Corsican was to gain in that campaign for France. After a sojourn of more than two years in his native country, Clive, holding the commission of lieutenant-colonel in the King’s army, was sent to the Koromandal coast as Governor of Fort St. David. For a while his services were diverted to Western India, where, in conjunction

with Admiral Watson, he attacked and reduced the piratical stronghold of Gheriah. Thence he proceeded to Madras in time to be selected as the commander of the troops who were to conquer Bengal.

Clive’s force, consisting, exclusive of the men in the Cumberland, of 800 Europeans, 1,200 native soldiers, and a due proportion of artillery, joined the remnants of Major Kilpatrick’s detachment, which had been much reduced by disease, on the 20th December. Just seven days later the fleet ascended the Hugli. On the 29th, the enemy were dislodged from the fort of Bajbaj. The action which took place there, whilst in its details it reflects no credit on the generalship of Clive, was yet so far decisive in its result that it terrified the enemy’s general into the abandonment of Calcutta. That place, left with a garrison of only 500 men, surrendered, without attempting a serious resistance, on the 2nd January. Prompt to strike, and anxious at once to terrify the Nuwab and to replenish the coffers of his countrymen, Clive, three days later, despatched a force to storm and sack Hugli, reputed to be the richest town within a reasonable distance of Calcutta. On the 9th the place was taken. The victors found, to their disappointment, that the more valuable of its stores had been, in anticipation of the attack, removed to the Dutch factory at Chinsurah.

But Siraju’d daulah had not yet been terrified. Raising an army said to have consisted of 18,000 horse, 15,000 foot, 10,000 armed followers, and forty guns, he marched on Calcutta. Clive, who was encamped at Kasipur, observing, on the 2nd February, that advanced parties of the Nuwab’s army were defiling upon the plain to the right of the Damdam road, and there taking up a position threatening Calcutta, made an ineffectual attempt to hinder them. The Nuwab arrived with his main body on the 3rd, and encamped just beyond the general line of the Maratha ditch. The following morning Fortune directed to the happiest results an action which seemed at first

pregnant with destruction to the English. It had been the intention of Clive to surprise the Nuwab’s army and to seize his person; but, misled by a thick fog he found himself at 8 o’clock in the morning in the middle of the enemy’s camp and encompassed by his troops. He extricated himself by simply daring to move forwards. The intrepidity of the attempt so intimidated the Nuwab that he drew off his army, and on the 9th February signed a treaty, by which he restored to the English more than their former privileges, and promised the restoration of the property seized at the capture of Calcutta.

But Clive was not yet satisfied. War had been declared between France and England. His experience in Southern India had shown him how dangerous to English interests would be an active alliance between the French and a strong native power. In the Karnatak he had been able to balance one native force against another. In Bengal such a policy was impossible, for the Nuwab was supreme, and his great officers had not as yet shown themselves impressionable. Then, again, Clive’s orders had been to return with his little army to Madras as soon as he should have reconquered Calcutta. But how, in the face of the possibility of an alliance between the Nuwab and the French, could he abandon Calcutta? To do so would be, he felt, to court for the English settlement permanent destruction. The French general, Bussy, was supreme at Haidarabad, possessed in real sovereignty the northern Sirkars, and rumour had even then pointed to the probability of his entering into negotiations with the Nuwab of Bengal. Under these circumstances the clear military eye of Clive saw but one course consistent with safety. In the presence of two enemies not yet united, but likely to be united, he must strike down one without delay. He would then be able to oppose to the other his undivided forces.

On this policy Clive acted. In spite of the prohibition of the Nuwab, he struck a blow at the French settlement of Chandranagar

(Chandernagor), intimidated or bribed to idleness the Nuwab’s general marching to its relief, and took the French fort (March 23rd).

This high-handed proceeding filled the mind of Siraju’d daulah with anger and fear. It is impossible for a fair-minded reader to examine the circumstances which surrounded this unfortunate Prince from the time when Clive frightened him into signing the treaty of the 9th February until he met his end after Plassey, without feeling for him deep commiseration. His attitude was that of a netted tiger surrounded by enemies whom he feared and hated, but could not crush. Imagine this boy, for he had not yet seen twenty summers, raised in the purple – for his birth was nearly contemporaneous with the accession of his grandfather to power – brought up in the lap of luxury, accustomed to the gratification of every whim, unendowed by nature with the strength of character which would counterbalance these grave disadvantages, invested with a power which he had been taught to regard as uncontrollable – imagine this boy set to play the game of empire against one of the coolest and most calculating warriors of the day, a man perfectly comprehending the end at which he was aiming, who had mastered the character of his rival and of the men by whom that rival was surrounded, who was restrained by no scruples, and who was as bold and decided as his rival was wavering and ready to proceed from one extreme to another. But this does not represent the whole situation. The boy so unevenly pitted against the Englishman was further handicapped by a constant dread of invasion by the Afghans from the north and by the Marathas from the west. He was afraid, therefore, to put out all his strength to crush the English, lest he should be assailed on his flank or on his rear. This dread added to his native uncertainty, and caused him alternately to cringe to or to threaten his rival. But he was more heavily handicapped still. I have said that his rival was restrained by no scruples. The truth of this remark is borne out by the fact that whilst

the unhappy boy Nuwab was the sport of the passion to which the event of the moment gave mastery in his breast, the Englishman was engaged slowly, persistently, and continuously in undermining his position in his own Court, in seducing his generals, and in corrupting his courtiers. When the actual contest came, though individuals here and there were faithful, there was not a single great interest in Murshidabad which was not pledged to support the cause of the foreigner. The Nuwab had even been terrified into removing from his capital and dismissing to Bhagulpur, a hundred miles distant, the one party which would have been able to render him effectual support, a body of Frenchmen commanded by M. Law!

The final crisis was precipitated by a curious accident. Whilst the wordy contest between the Calcutta Council and the Nuwab which marked every day of the three months which followed the capture of Chandranagar was progressing, Siraju’d daulah, always distrustful of the English, had located his army, nominally commanded in chief by his prime minister, Rajah Dulab Ram, and supported by a considerable corps under Mir Jafar Khan – a high nobleman who had married his aunt – at Palasi, a town in the island of Kasimbazar – called an island because whilst the base of the triangle which composed it was watered by the Ganges, the western side on which lies Palasi is formed by the Bhagirathi, and the eastern by the Jalanghi. Palasi is twenty-two miles from Murshidabad.

Clive and the Calcutta Council had taken great offence at the location of the Nuwab’s army at Palasi, and had affected to regard it as a sign of hostile intent towards themselves. When the relations between the two rival parties were in a state of great tension, a messenger arrived in Calcutta, the bearer of a letter purporting to come from the great Maratha chieftain of Birar, and containing a proposal that he should march with 120,000 men into Bengal and co-operate with the English against the Nuwab.

For once the clear brain of the director of the English policy was at fault. Clive could not feel quite sure that the letter might not be a device of the Nuwab to ascertain beyond a doubt the feelings of the English towards himself. Various circumstances seemed to favour this view. But if his vision was for a moment clouded, the political action of Clive was clear, prompt, decided, and correct. Treating the letter as though it were genuine, he sent it to Siraju’d daulah, ostensibly as a proof of his confidence, and as the ground for a request that he would no longer keep his army in the field. The plan succeeded. The letter was genuine. The Nuwab was completely taken in. He recalled his army to Murshidabad. For the first time since he had retreated from Calcutta he believed the friendly protestations of the English.

Never had he less cause to believe them. At that very time the Baths, the great financiers of Murshidabad, were committed against their Native ruler; Mir Jafar had been gained over by the English; the dewan, Rajah Dulab Ram, was a party to the same compact. The bargain with the two latter had been drawn up, and only awaited signature.

The conduct of Siraju’d daulah himself gave the finishing touch to the conspiracy. Up to the moment of the receipt of the Maratha’s letter his fear of the English had somewhat restrained the tyrannical instincts in which he had been wont to indulge at the expense of his own immediate surroundings. But the frankness of Clive in transmitting to him that letter had produced within him a great revulsion of feeling. That revulsion was accompanied by a corresponding change of conduct. Secure now, as he believed, of the friendship of the English, he began to threaten his nobles. Mir Jafar, the most powerful of them all, was the first intended victim. But this chief, quasi-independent, would not be crushed. Taking refuge in his palace, and summoning his friends and followers, he bade defiance to the Nuwab. Whilst thus acting towards his master, he urged upon Mr. Watts,

the English agent at Murshidabad, to press that the English troops should take the field and commence operations at once.

The treaty by which Clive and the English Council had engaged to raise Mir Jafar Khan to the quasi-royal seat of his master, on condition of his co-operation in the field, and of his bestowal upon them of large sums of money, had by this time reached Calcutta, signed and sealed. Clive then had no further reason for temporising. He boldly then threw off the mask, and marched, on the 13th June, from Chandranagar.

The same day Clive dismissed from his camp two agents of the Nuwab, instructing them to notify to their master that he was marching on Murshidabad, with the object of referring the English complaints against him, which he enumerated, to a commission of five officers of his Government. He gave the names of those officers. They were the men who had conspired with him against their master.

Mr. Watts, the English agent, had received, previously, instructions to leave Murshidabad, the moment he should conceive the moment opportune. He and his subordinates fled from that place on the lath June, and reached Clive’s camp in safety. The evasion of Mr. Watts caused the scales to fall from the eyes of the unhappy Siraju’d daulah. He saw on the moment that the English were in league with Mir Jafar. Always in extremes, he was as anxious now to conciliate, as an hour earlier he had been eager to punish, his powerful vassal. His overtures caused Mir Jafar to make a show of submission, whilst he secretly warned Clive. The other conspirators made similar pretences. The Nuwab then ordered the army to march promptly to take up its former position at Palasi. But here again he was met by unlooked-for opposition. When the leaders of an army are disaffected, indiscipline almost invariably permeates the rank and file. So it was now. Large arrears were owing to the men, and they had no great inclination to risk their lives for a personal cause, For it had come to this.

The cause did not present itself to their eyes as one in which the national interests were concerned, as one which involved the independence of Bengal. To the vast majority it seemed merely to balance one chieftain against another – Siraju’d daulah, the grandson of a usurper, against Mir Jafar, the most powerful noble of the province. It took three days to restore order among the soldiers, and this result was effected only by the distribution of large sums of money, and of promises. The delay was unfortunate, for the army did not reach its position at Palasi till the 21st (June).

Meanwhile Clive, marching from Chandranagar on the 13th, arrived, on the 16th, at Palti, a town on the western bank of the Bhagirathi, about six miles above its junction with the Jalanghi. Hence he despatched, on the 17th, a force composed of 200 Europeans, 500 sepoys, with a field gun and a small howitzer, under Major Eyre Coote, of the 39th Foot, to gain possession of Katwa, a town and fort some twelve miles distant. The Occupation of Katwa was important, for not only did the fort contain large supplies of grain and military stores, but its position, covered by the little river Aji, rendered it sufficiently strong to serve as a base whence Clive could operate against the island. The native commander at Katwa surrendered the place to Eyre Coote after only a show of resistance. Clive and the rest of the force arrived there the same evening, and at once occupied the huts and houses in the town and fort. It was a timely shelter, for the periodical rainy season opened with great violence the very next day.

A few miles of ground and the river Bhagirathi now lay between Clive and Siraju’d daulah. Since his departure from Chandranagar, the former had despatched daily missives to Mir Jafar, but up to the time of his arrival at Katwa he had received but one reply, dated the 16th, apprising him of his reconciliation with the Nuwab, and of his resolve to carry out the engagements he had made with the English. On the 20th,

however, two communications, bearing a more doubtful significance, were received. The first was the report of a messenger returned from conveying a message to Mir Jafar. This man’s report breathed so uncertain a sound that Clive wrote to the Select Committee in Calcutta for further orders, expressed his disinclination to risk his troops without the certainty of co-operation on the part of Mir Jafar, and his resolution, if that co-operation were wanting, to fortify himself at Katwa and await the cessation of the rainy season.

The second communication, received the evening of the same day, was in the form of a letter written by Mir Jafar himself the previous day, just as he was starting for Palasi. In this he stated that he was on the point of setting out; that he was to be posted on one flank of the army; that on his arrival at Palasi he would despatch more explicit information. That was positively all. The letter contained no suggestion as to concert between the two confederates.

This letter did not go very far to clear away the embarrassment which the communication of the messenger had caused in the mind of the English leader. The questions “how to act,” “whether to act at all,” had to be solved, and solved without delay. Could he, dare he, with an army consisting, all told, of 8,000 men, of whom about one third only were Europeans, cross the Bhagirathi and attack an army of some 50,000 men, relying on the promises of the commander of less than one-third of those fifty thousand that he would betray his master and join him during the action? That was the question. Should he decide in the negative, two alternatives presented themselves: the one, to fortify himself at Katwa and await the cessation of the rains; the other, to return to Calcutta. But was either feasible? After having announced to all Bengal his intention to depose Siraju’d daulah – for his plans had been the talk of the bazars and of the camp – could he, dare he, risk the loss of prestige which inaction or a retreat would involve? Could he, dare he,

risk the cooling of his relations with his native confederates, their certain reconciliation with their master, a possible uprising in his rear? Advance without the co-operation of Mir Jafar seemed to be destruction; a halt at Katwa would be the middle course – so dear to prudent men – involving always a double danger; the third course, the retreat to Calcutta, meant an eternal farewell to the ambitious and mercenary hopes that had been aroused. Balancing the pros and cons in his mind, Clive, keenly alive to the importance of producing an impression upon the minds of the natives by display and by numbers, despatched that evening a pressing letter to the Rajah of Bardhwan, begging him to join him, if only with a thousand horsemen. He then summoned all the officers in his camp above the rank of subaltern to a council of war.

There came to that council, including Clive, twenty officers, some of them, such as Eyre Coote, of the 89th, and James Kilpatrick, of the Madras army, men of capacity and mental power. The question Clive put before them was whether, under existing circumstances, and without other assistance, the army should at once cross into the island of Kasimbazar, and at all events attack the Nuwab; or whether they should fortify themselves at Katwa and wait till the monsoon was over, trusting then to assistance from the Marathas, or some other native power. Contrary to all custom, Clive gave his own vote first, and invited the others to follow his example in order of seniority. Clive voted against immediate action.

On the same side voted Major Kilpatrick, commanding the Company’s troops, Major Archibald Grant, of the 89th, Captains Waggoner and Corneille, of the same regiment, Captain Fischer, Bengal Service, Captains Gaupp and Rumbold, Madras Service, Captains Palmer and Molitor, Bombay Service, Captain Jennings, commanding the Artillery, and Captain Parshaw, whose service I have been unable to ascertain. Major Eyre Coote took a view totally opposed to theirs. That gallant soldier

showed the capacity for command which he possessed, and which he displayed throughout a long and distinguished military career, when he declared in favour of immediate advance, on the following grounds. First, he argued, they had met with nothing but success; the spirit of the troops was high, and that spirit would be damped by delay. Then he urged that delay would be prejudicial in another sense, inasmuch as it would allow time for the French leader, M. Law, who had been promptly summoned from Bhagalpur to join the Nuwab, to arrive; that his arrival would not only greatly strengthen that ruler, but would impair the efficiency of the English force, because the French who had been enlisted into its ranks after the fall of Chandranagar would take the first opportunity to desert. Finally, he protested with all his force against the half measure of halting at Katwa. If, he declared, it were thought not advisable to come to immediate action – though he held a contrary opinion – it would be more proper to return to Calcutta at once. He dwelt, however, on the disgrace which such a measure would entail on the army, and the injury it would cause to the Company’s interests. Major Eyre Coote was supported in his view by Captains Alexander Grant, Cudmore, Muir, and Carstairs, of the Bengal Service; by Captain Campbell, of the Madras, and by Captain Armstrong, of the Bombay Service. The majority against him, however, was thirteen to seven. By nearly two to one the council of war decided not to fight.

The members of the council separated, and Clive was left alone. The decision had not relieved the anxiety which pressed upon him. Strolling to a piece of ground shaded by a clump of trees, he sat down, and passed in review the arguments which had been urged on both sides. A thorough soldier himself, a man who had proved on more than one field that boldness was prudence, and that bastard-prudence carried within it the germs of destruction, he could not long resist the soundness of the views which had been so forcibly urged by Eyre Coote and his

supporters. At the end of an hour’s reflection, all doubt had disappeared. He was once more firm, self-reliant, and confident. Rising, he set out to return to his quarters. On his way thither he met Major Eyre Coote. Simply informing him that he had changed his mind, and intended to fight, Clive entered his quarters and dictated orders for the passage of the river the following morning.

Deducting the sick and a small guard left at Katwa, the army directed to march against the Nuwab consisted of 95013 European infantry and 100 European artillery, 50 English sailors, a small detail of native lascars, and 2,100 native troops. The artillery train was composed of eight 6-pounders and two small howitzers. Obeying the orders issued the night before, this little force marched down the banks of the Bhagirathi at daybreak of the 22nd June, and began the crossing in the boats which had accompanied it from Chandranagar. It encountered no opposition, and by 4 o’clock the same afternoon it was securely planted on the left bank. Here Clive received another letter from Mir Jafar, informing him that the Nuwab had halted at Mankarah, a village six miles from Kasimbazar, and there intended to entrench himself. The Mir suggested that the English should march up the eastern side of the triangle which forms the island and surprise him.

Such an operation would have cut off Clive from his base, which was now the river Bhagirathi, and have entailed a march round the arc of a circle, whilst his enemy, traversing the chord, could sever him from all his communications. It was not very hopeful to receive such advice from a confederate, himself a soldier who had commanded in many a campaign. Clive met it in the direct and straightforward way calculated to force a decision. He sent back the messenger with the answer that he would march towards Palasi without delay; that the next day he would march six miles further to Daudpur; but that if,

reaching that village, Mir Jafar should not join him, he would make peace with the Nuwab.

The distance to Palasi from the camp on the Bhagirathi, whence this message was despatched, was fifteen miles. To accomplish those fifteen miles the little army marched at sunset the same day, the 22nd, following the windings of the Bhagirathi, up the stream of which their boats, containing their supplies and auxiliary stores, were towed. After eight hours of extreme fatigue, the overflow of recent inundations causing the water to rise often up to their waists, whilst a deluge poured upon them from above, they reached, weary and worn out, at 1 o’clock in the morning of the 23rd, the village of Palasi. Traversing this village, they halted and bivouacked in a large mango grove a short distance beyond it. Here, to their surprise, the sound of martial music reached their ears, plainly signifying that the Nuwab was within striking distance of them.

The mango grove which formed the bivouac of the English force was, in fact, little more than a mile from the Nuwab’s encampment. It was 800 yards in length and 300 in breadth, and was surrounded by an earth-bank and ditch. In its length it was diagonal to the river, for whilst the Bhagirathi flowed about fifty yards from its north-west angle, four times that distance intervened between it and the south-western corner. The trees in it were, as is usual in India, planted in regular rows.14 Just beyond the grove stood a hunting-box belonging to the Nuwab, surrounded by a masonry wall. Of this, Clive, as soon as the sounds of martial music to which I have adverted reached his ears, detached a small force to take possession. It is now time that I should explain how it was that such music came to be in his close vicinity.

The reader will recollect that in consequence of the mutiny of his troops at Murshidabad, the Nuwab had been forced to

delay his march from that place till the 19th June. On that day he set out, but on that same day he heard of the arrival of the English army at Katwa. Judging from his knowledge of the character of their leader that they would cross the Bhagirathi and march on Palasi without delay, he came to the conclusion that he had been forestalled at that place, and that it would be better for him to halt at Mankarah and watch thence the course of events. But when, on the 21st, he learned that Clive was still halting at Katwa, his resolution revived, and he marched at once to his old encampment at Palasi about one mile to the north of the grove of which I have spoken. He had taken his post here twenty-six hours before the English reached the grove.

His army was strong in numbers. It consisted of 35,000 infantry of all sorts; men not trained in the European fashion, but of the stamp of those which may be seen in the present day in and about the chief towns of the territories of native princes of the second or third rank. They were, in fact, men imperfectly trained and imperfectly armed, and, in the rigid sense of the word, undisciplined. His cavalry, said to have amounted to about 15,000, were better. They were mostly Patens from the north, the race of which the Indian irregular horse of the present day is formed, excellent light cavalry, well mounted, armed with swords or long spears. His artillery was better still. It consisted of fifty-three pieces, mostly of heavy calibres, 32, 24, and 18-pounders. But what constituted its greatest strength was the presence with that arm, to support the native gunners and to work and direct their own field-pieces, of forty to fifty Frenchmen – who had been allowed to remain when Law with the main body had been dismissed – commanded by M. St. Frais, formerly one of the Council of

. Chandranagar. These men were animated by a very bitter feeling against the Englishman who had despoiled their flourishing settlement.

This army thus strong in numbers occupied likewise a strong position. The intrenched works which covered it rested on the river, extended inland in a line perpendicular to it for about 200 yards, and then swept round to the north-east at an obtuse angle for about three miles. At this angle was a redoubt mounted with cannon. Three hundred yards east of this, and in front of the line of intrenchments, was a hillock covered with jungle, and about 800 yards to the south, nearer the grove occupied by the English was a tank, and 100 yards still nearer a larger tank. Both of these were surrounded by large mounds of earth at some distance from their margins. It is important to keep the mind fixed on these points when following the movements of the two armies.

At daybreak on the 23rd, the Nuwab’s army marched out of its intrenchments and took up the following positions. The French, with four field-pieces, took post at the larger tank, nearest the English position, about half a mile from it. Between them and the river, and in a line with them, were placed two heavy guns under a native officer; behind them again, and supporting them, were the Nuwab’s best troops, a body of 5,000 horse and 7,000 foot, commanded by his one faithful general, Mir Mudin Khan, by the side of whom served the prince’s Hindu favourite, Mohan Lid. From the rearmost position of Mir Main, the rest of the army formed a curve in the direction of the village of Palasi, the right resting on the hillock covered with jungle of which I have spoken, the left on a point covering the south-eastern angle of Clive’s grove, at a distance of about 800 yards from it. The intervals were crammed with dense masses of horse and foot, artillery being interspersed between the masses or columns. The troops forming this curve, numbering about 45,000, were commanded by the traitor confederates, Rajah Dulab Ram, Yar Lutf Khan, and Mir Jafar. The first was on the right, the second in the centre, Mir Jafar on the left nearest the English. The position was a strong one,

for the English could not attack the point which barred their progress – that occupied by the French and Mir Main Khan – without exposing their right to a flank attack. In fact, they were almost surrounded, and, unless treason had played her part, they had been doomed.

From the roof of the hunting-box Clive watched the movements, as they gradually developed themselves, of the army of Siraju’d daulah. As Mir Mudin took up his position, as the corps of Mir Jafar, Yar Lutf, and Dulab Ram poured out their myriads until the mango grove his men occupied was not only flanked, but the extreme end of the arc formed by those myriads threatened to even overlap its rear, he could not conceal his astonishment at the numbers against whom he was about to hurl his tiny band. “What if they should all be true to their master!” was a thought which must more than once have traversed his brain as he witnessed that long defiling. It was too late to think of that, however, and Clive, true to his military instinct, which in the time of danger was always sound, resolved to meet this bold display by a corresponding demonstration. Accordingly he ordered his men to advance from the grove, and drew them up in line in front of it, their left resting on the hunting-box, which was immediately on the river. In the centre of the line he placed his Europeans, flanked on both sides by three 6-pounders; on their right and left he posted the native troops in two equal divisions. He detached at the same time a small party with two 6-pounders and two howitzers to occupy some brick-kilns about 200 yards in front of the left (the native) division of his little army.

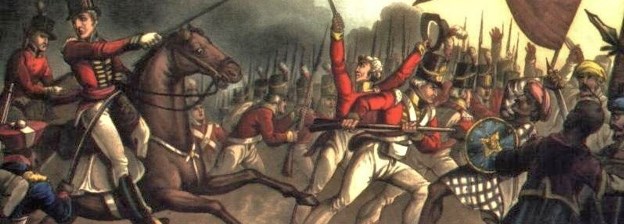

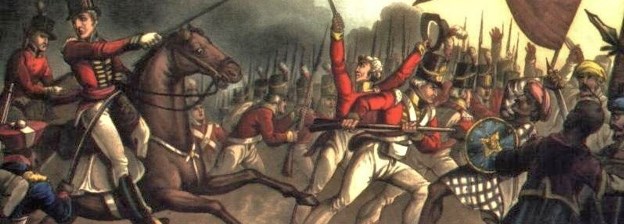

By 8 o’clock in the morning of this memorable day, the preparations on both sides were completed. The French under St. Frais opened the battle by firing one of their guns which, well directed, took effect on the British line. The discharge of this single gun was the signal for the opening of a heavy and continuous fire from the enemy’s whole line, from the guns in

The Battle of Plassey, 23 June 1757

Reference

A. Position of the British army at 8 in the morning.

B. Guns advanced to check the fire of the French.

C. Nuwab’s army in three divisions.

D. The tank occupied up to 3 p.m. by the French supported in the rear by Mudin Khan.

E. F. The redoubt and mound taken, at ½ past 4 o’clock.

G. The Nuwab’s hunting box.

front as well as from those in the curve. The English guns returned the fire with considerable effect. Still, however true might have been the aim of the English gunners, the disparity in numbers, in the weight of metal, and in guns was too great to allow the game to be continued long by the weaker party. Though ten of the enemy’s men might fall to one of the English, the advantage would still be with the enemy. Clive was made to feel this when, at the end of the first half hour, thirty of his men had been placed hors de combat. He accordingly determined to give his troops the shelter which the grove and its bank would afford. Leaving still an advanced party at the brick-kilns, and another at the hunting-box, he effected this withdrawal movement in perfect order, though under the shouts and fire of the enemy. These were so elated that they advanced their guns much nearer and began to fire with greater vivacity. Clive, however, had now found the shelter he desired, and whilst the balls from the enemy’s guns, cutting the air at too high a level, did great damage to the trees in the grove, he made the bulk of his men sit down under the bank, whilst small parties should bore holes to serve as embrasures for his field-pieces. From this new position his guns soon opened fire, and maintained it with so much vigour and in so true a direction that several of the enemy’s gunners were killed or wounded, and every now and again explosions of their ammunition were heard. Protected by the bank, the proportion of the casualties of the English now lessened considerably, whilst there was no abatement of those of the masses opposed to them. Still, at the end of three hours, no great or decisive effect had been produced, the enemy’s fire had shown no signs of diminishing, nor had their position varied. No symptoms of co-operation on the part of Mir Jafar were visible, nor, in the face of such enormous masses of men, who had it in their power, if true to their prince, to surround and overwhelm any party which should attempt the key of the position, held by

Mir Mudin Khan, did any mode of bettering the condition of affairs seem to offer. This was certainly the opinion of Clive when, at 11 o’clock, he summoned his principal officers to his side. Nor could he, after consultation with them, arrive at any other conclusion than this – that it was advisable to maintain the position till after nightfall, and at midnight try the effect of an attack on the enemy’s camp.

The decision was sound under the circumstances, especially as it was subordinate to any incidents which might, in the long interval of twelve hours, occur to alter it. Such an incident did occur very soon after the conference. There fell then, and continued for an hour, one of those heavy pelting showers so common during the rainy season. The English had their tarpaulins ready to cover their ammunition, which in consequence sustained but little injury from the rain. The enemy took no such precautions, and their powder suffered accordingly. The result was soon shown by a general slacking of their fire. Believing that the English were in a similar plight, Mir Mudin Khan advanced with a body of horsemen towards the grove to take advantage of it. The English, however, received him with a heavy grape fire, which not only drove back his men, but mortally wounded their leader.

This was the crisis of the day. As long as Mir Mudin lived, the chances of Siraju’d daulah, surrounded though he was by traitors, were not quite desperate. The fidelity of that true and capable soldier might, under any circumstances, save him. But his death was a loss which could not be repaired. It is probable that some such conviction penetrated the heart of the unfortunate young prince when the news of the calamity reached him. He at once sent for Mir Jafar, and besought him in the most abject terms to be true to him and to defend him. He reminded him of the loyalty he had always displayed towards his grandfather, Ali Vardi Khan, of his relationship to himself; then taking off his turban, and casting it on the ground before him,

he exclaimed, “Jafar, that turban thou must defend.” Those who are acquainted with the manners of Eastern nations will realise that no more pathetic, no more heartrending, appeal could be made by a prince to a subject.

Mir Jafar Khan responded to it with apparent, sincerity. Placing – in the respectful manner which indicates devotion – his crossed hands on his breast, and bowing over them, he promised to exert himself to the utmost. When he made that gesture and when he uttered those words he was lying. Never was he more firmly resolved than at that moment to betray his master. Quitting the presence of the Nuwab he galloped back to his troops, and despatched a letter to Clive, informing him of what had happened, and urging him to push on immediately; or, in no case to defer the attack beyond the night. That the messenger did not reach his destination till too late for Clive to profit by the letter, detracts not one whit from the baseness of the man who, fresh from such an interview, wrote and sent it!

But Mir Jafar was not the only traitor. The loss of his best officer, coinciding with the unfortunate damping of the ammunition, had completely unnerved Siraju’d daulah. Scarcely had Mir Jafar left him, than he turned to the commander of his right wing, Rajah Dulab Ram, for support and consolation. The counsel which this man – likewise one of the conspirators – gave him, was of a most insidious character. Playing upon his fears, he continually urged him to issue orders to the army to retire behind the intrenchment; this order issued, he should quit the field, and leave the result in confidence to his generals. In an evil hour the wretched youth, incapable at such a moment of thinking soundly and clearly, followed the insidious advice, issued the order, and, mounting a camel, rode – followed by 2,000 horsemen – to Murshidabad.

The three traitorous generals were now masters of the position. Their object being to entice the English to come on, they

began the retiring movement which the Nuwab had sanctioned. They had reckoned, however, without St. Frais and his Frenchmen. These gallant men remained true to their master in the hour of supreme peril, and declined to quit a position which, supported by the troops of Mir Mudin, they had maintained against the whole British force. But Mir Mudin had been killed, his troops were following the rest of the army, and St. Frais stood there almost without support. To understand what followed, I must ask the reader to accompany me to the grove.

I left Clive and his gallant soldiers repulsing the attack which cost the Nuwab his one faithful commander. The vital consequences of this repulse never presented themselves for a moment to the imagination of the English leader. It never occurred to him that it might lead to the flight of the Nuwab, and to the retirement of his troops from a position which they had held successfully, and from which they still threatened the grove. There can be no doubt but that, at this period of the action, Clive had made up his mind to hold the grove at all hazards till nightfall, and then, relying upon the co-operation of Mir Jafar and his friends, to make his supreme effort. Satisfied that this was the only course to be followed, he had entered the hunting-box and lain down to take some rest, giving orders that he should be roused if the enemy should make any change in their position. He had not been long absent when Major Kilpatrick noticed the retiring movement I have already described. He did not know, and probably did not care, to what cause to attribute it; he only saw that the French were being deserted, and that a splendid opportunity offered to carry their position at the tank, and cannonade thence the retiring enemy. Quick as the thought he moved rapidly from the grove towards the tank with about 250 Europeans and two field-pieces, sending an officer to Clive to explain his intentions and their reason.

It is said that the officer found Clive asleep. The message, however, completely roused him, and, angry that any officer should have dared to make an important movement without his orders, he ran to the detachment and severely reprimanded Kilpatrick. A glance at the situation, however, satisfied him that Kilpatrick had only done that which he himself would have ordered him to do had he been on the spot. He realised that the moment for decisive action had arrived. He sent back Kilpatrick, then, with orders to bring on the rest of the army, and continued the movement which that officer had initiated.

St. Frais, on his side, had recognised that the retreat of the Nuwab’s army had compromised him, and that he was quite unable, with his handful, to resist the whole British force, which, a few minutes later, he saw issuing from the grove in his direction. Resolved, however, to dispute every inch of the ground, he fired a parting shot, then, limbering up, fell back in perfect order to the redoubt at the corner of the intrenchment. Here he planted his field-pieces ready to act again.

Meanwhile, two of the three divisions of the enemy’s army were marching towards the intrenchment. It was observed, however, that the third division, that on the left, nearest to the grove, commanded by Mir Jafar, lingered behind the rest, and that when its rearmost file had reached a point in a line with the northern end of the grove, the whole division wheeled to the left and marched in that direction. Clive had no means of recognising that these were the troops of his confederate, but, believing that they had a design upon his baggage, he detached a party of Europeans with a field-piece to check them. The fire of the field-piece had its effect, in so far that it prevented a further advance in that direction. But the division continued to remain separate from the rest of the Nuwab’s army.

Clive, himself, meanwhile, had reached the tank from which St. Frais had retreated, and had begun thence a vigorous cannonade of the enemy’s position behind the intrenchment. What followed

can be well understood, if it be borne in mind that whilst the leaders of the Nuwab’s army had been gained over, the rank and file, and the vast majority of the officers, were faithful to their master. They had not been entrusted with the secret, and being soldiers and superior in numbers to the attacking party, they were in no mood to permit that party to cannonade them with impunity. No sooner, then, did the shot from the British cannon begin to take effect in their ranks, than they issued from the intrenchment – cavalry, infantry, and artillery – and opened a heavy fire upon the British force.

The real battle now began. Clive, seriously incommoded by this new move on the part of the enemy, quitted his position and advanced nearer to the intrenchment. Posting then half his infantry and half his artillery on the mound of the lesser tank, the greater part of the remaining moiety on a rising ground 200 yards to the left of it, and detaching 160 men, picked natives and Europeans, to lodge themselves behind a tank close to the intrenchment, he opened from the first and second positions a very heavy artillery fire, whilst from the third the musketry fire should be well sustained and well aimed. This masterly movement, well carried into execution, caused the enemy great loss, and threw the cattle attached to their guns into great confusion. In vain did St. Frais ply his guns from the redoubt, the matchlockmen pour in volley after volley from the hillock to the east of it, and from the intrenchments. In vain did their swarthy troopers make charge after charge. Masses without a leader were fighting against a man whose clearness of vision was never so marked, whose judgment was never so infallible, whose execution was never so decisive as when he was on the battlefield. What chance had they, brave as they were, in a battle which their leaders had sold? As they still fought, Clive noticed that the division of their troops which he had at first believed had designs on his baggage, still remained isolated from the rest, and took no part in the battle. Suddenly it dawned upon

.him that it must be the division of Mir Jafar. Immensely relieved by this discovery, inasmuch as it freed him from all apprehension of an attack on his flank or rear, he resolved to make a supreme effort to carry the redoubt held by St. Frais, and the hill to the east of it. With this object, he formed two strong detachments, and sent them simultaneously against the two points indicated, supporting them from the rear by the main body in the centre. The hill was first gained and carried without firing a shot. The movement against the redoubt was not less successful, for St. Frais, abandoned, isolated, and threatened, had no resource but to retire. The possession of this position decided the day. Thenceforward all resistance ceased. By 5 o’clock the English were in the possession of the whole intrenchment and camp. The victory of Plassey had been won 1 It had cost the victors seven European and sixteen native soldiers killed, thirteen European and thirty-six natives wounded.

Plassey was a very decisive battle. The effects of it are felt this day by more than two hundred and fifty millions of people. Whilst the empire founded by the Mughuls was rapidly decaying, that victory introduced into their richest province, in a commanding position, another foreign race, active, capable, and daring, bringing with them the new ideas, the new blood, the love of justice, of tolerance, of order, the capacity of enforcing these principles, which were necessary to infuse a new and a better life into the Hindustan of the last century. There never was a battle in which the consequences were so vast, so immediate, and so permanent. From the very morrow of the victory the English became virtual masters of Bengal, Bihar, and Orisa. During the century which followed, but one serious attempt was made, and that to be presently related, to cast off the yoke virtually imposed by Plassey, whilst from the base it gave them, a base resting on the sea and, with proper care, unassailable, they were able to extend their authority beyond the Indus, their

influence amongst peoples of whose existence even Europe was at the time profoundly ignorant. It was Plassey which made England the greatest Muhammadan power in the world; Plassey which forced her to become one of the main factors in the settlement of the burning Eastern question; Plassey which necessitated the conquest and colonisation of the Cape of Good Hope, of the Mauritius, the protectorship over Egypt; Plassey which gave to the sons of her middle classes the finest field for the development of their talent and industry the world has ever known; to her aristocracy unrivalled opportunities for the display of administrative power; to her merchants and manufacturers customers whose enormous demands almost compensate for the hostile tariffs of her rivals, and, alas I even of her colonies; to the skilled artisan remunerative employment; to her people generally a noble feeling of pride in the greatness and glory of the empire of which a little island in the Atlantic is the parent stem, Hindustan the noblest branch; it was Plassey which, in its consequences, brought consolation to that little island for the loss of America, and which, whilst, in those consequences, it has concentrated upon it the envy of the other nations of Europe, has given to her children the sense of responsibility, of the necessity of maintaining a great position, the conviction of which underlies the thought of every true Englishman.

Yes! As a victory, Plassey was, in its consequences, perhaps the greatest ever gained. But as a battle it is not, in my opinion, a matter to be very proud of. In the first place, it was not a fair fight. Who can doubt that if the three principal generals of Siraju’d daulah had been faithful to their master Plassey would not have been won? Up to the time of the death of Mir Main Khan the English had made no progress; they had even been forced to retire. They could have made no impression on their enemy had the Nuwab’s army, led by men loyal to their master, simply maintained their position. An advance against

the French guns meant an exposure of their right flank to some 40,000 men. It was not to be thought of. It was only when treason had done her work, when treason had driven the Nuwab from the field, when treason had removed his army from its commanding position, that Clive was able to advance without the certainty of being annihilated. Plassey, then, though a decisive, can never be considered a great battle.

There was that about the events preceding it, occurring during its progress, and following it, which no honourable man can contemplate without disgust and repulsion. Not one actor in the drama was free from the stain which connection with dishonour always causes. The bargaining of Clive and the Calcutta Council with Mir Jafar and the other traitors, the episode with Amichand, though they form no part of the military history of the battle, cannot be wholly ignored when considering its consequences. The greed for money, the ever increasing demand for the augmentation of the sum originally asked for, the dishonouring trick by which a confederate was to be baulked of his share in the spoil; these are actions, the contemplation of which makes, and will always make, the heart of an honest man burn with indignation. Then, to single out one, the chiefest of the conspirators, Mir Jafar Khan. This man had possessed honourable instincts. Ten years before Plassey had been fought, Ali Vardi Khan had removed him from his command because he had retreated before the Marathas. The officer who replaced him advanced and defeated those warriors; then coming to Mir Jafar, offered to make him governor of Bihar if he would aid in deposing Ali Vardi. Mir Jafar refused then: – but in 1757 we see this man – then so loyal – conspiring with a foreign people, of whose power he was conscious, to seat himself on the throne – for virtually it was a throne – of his master. To accomplish this selfish personal end, he hesitates not to become a perjuror of the deepest dye; to doom to a violent death the nephew to whom he had sworn obedience, and to sacrifice the

future of his country. If the people of India do indeed writhe under the sway of their foreign conquerors, they have to thank this Mir Jafar Khan, this man who sold their three richest provinces to the English that he might enjoy the mere pageantry of royalty.

It was indeed the merest pageantry. Soon was he made to learn that bitter truth that, by his own act, dominion in Bengal had departed from the Mughul. A tool, a cypher in the hands of the foreigners for whom he had betrayed his master, he was allowed to govern, never to rule. Well for him that he did not possess the power to dive into futurity and behold the representative of his name and office, an unhonoured pensioner of the people he had called in to subdue his country!

The name of Siraju’d daulah has been justly held up to obloquy in connection with the catastrophe of the Black Hole. Although, as I have shown, the Nuwab had not designed the death of our countrymen, still he made himself an accessory after the act, and must, therefore, bear the blame of the deed. Yet the hearts of those who condemn him most will scarcely steel themselves to the pity which the contemplation of his subsequent fate inspires. From the time when Clive beat up his quarters before Calcutta, to the hour of his death, the life of Siraju’d daulah was one of constant alarm and dread. He knew not whom to trust. He felt that he was betrayed, but he could not feel sure by whom. Confident one day that Clive was his enemy, believing the next that he was his friend – he could not resolve to offer him decided opposition, or to disarm in his presence. His vacillation, the child of uncertainty, completed his ruin. The body of Frenchmen whom, to please Clive, he had sent to Bhagalpur, might have saved Plassey. When he could no longer resist the conviction that Clive was his bitter, his irreconcilable enemy, he called to his councils the very men who had sworn to betray him Could there be a harder fate than this for a young boy suddenly raised to power, and not yet

satiated with the follies of youth? At Plassey, again, he was betrayed; betrayed at a moment when, had he been loyally supported, he might have rid himself for ever of the hated English. Inexorable fate still pursued him. Fleeing from the field, he reached Murshidabad that night, only to learn in the early morn of the defeat of his army. Terrified by the prospect before him, he embarked that night accompanied by his favourite wife, on a boat prepared for him by one still faithful adherent, hoping to reach the French advancing under Law from Bhagalpur. But at Rajmahal the strength of the rowers failed them, and he took refuge for the night in the buildings of a deserted garden. Here he was discovered and betrayed – again betrayed – and brought, bound like a common felon, into the presence of Mir Jafar. Trembling and weeping, he implored his life. It was a scene which recalls to the English reader another scene acted some seventy years previously, between Monmouth and James II. Mir Jafar was as inexorable as James. That night, by the express order of his son, Miran, Siraju’d daulah was stabbed to death in his cell.

He was more fortunate, and certainly less to be despised, than was Mir Jafar. Whatever may have been his faults, Siraju’d daulah had neither betrayed his master nor sold his country. Nay more, no unbiassed Englishman, sitting in judgment on the events which passed in the interval between the 9th February and the 23rd June, can deny that the name of Siraju’d daulah stands higher in the scale of honour than does the name of Clive. He was the only one of the principal actors in that tragic drama who did not attempt to deceive!

6. Long usage has, in this case, as in the cases of Calcutta, Pondichery, and Bombay, sanctioned an incorrect spelling. The proper rendering of the name of this place is Palasi, from the palls tree (Butea frondoea), which used to abound in the vicinity. The A’in-i-Akbari makes special mention of the palate as the wood of which the balls for the game of changan (hockey) by night were made in the time of Akbar. “His Majesty also plays at changan on dark nights, which caused much astonishment, even among clever players. The balls which are used at night are set on fire. For this purpose palls wood is used, which is very light, and burns for a long time.” – Blochmann’s d’in-i-Akbari, page 298.

7. Calcutta, or, as it was spelt by the natives, “Kalikata,” is mentioned in the A’in-i-Akbari of Abul Fazl, written in 1696. The village of Chatanati extended from the present mint to the Sobs bazaar. For these and other details regarding the making of Calcutta, I would refer the reader to a very remarkable pamphlet, Calcutta during the Last Century, written and given as a lecture by the late Professor Blochmann, MA., whose untimely death five years ago was a deadly blow to Oriental investigation. The little pamphlet, which ought to be preserved, was printed by Mr. Thomas Smith, City Press, Bentinck Street, Calcutta.

8. Mr. Wheeler states that the rebels were “routed by fifty English soldiers in front of the factory at Chatanati.” – Early Records of British India.

9. These were – the president, a vice-president and accomptant, a warehouse. keeper, a purser of marine, and a receiver of revenues and general manager.

10. Hamilton died that same year at Calcutta.

11. “I had in all three interviews with him (the Nuwab), the last in Darbar before seven, when he repeated his assurances to me, on the word of a soldier, that no harm should come to us; and, indeed, I believe his orders were only general that for that night we should be secured; and that what followed was the result of revenge and resentment in the breasts of the lower jemadars to whose custody we were delivered, for the number of their order killed during the siege.” – Mr. Holwell’s Narrative.

12. These were subsequently released, and joined the fleet at Falta.

13. In these were included 200 men of mixed native and Portuguese blood.

14. The last of these trees, Mr. Eastwick informs us, fell some years ago, and has been eaten by white ants. – Murray’s Handbook of Bengal, 1882.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()