Rana Bhim Singh (the reigning prince), who succeeded his brother in S. 1834 (A.D. 1778), was the fourth minor in the space of forty years who inherited Mewar; and the half century during which he has occupied the throne has been as fruitful in disaster as any period of her history already recorded. He was but eight years of age on his accession, and remained under his mother’s tutelage long after his minority had expired. This subjection fixed his character; naturally defective in energy, and impaired by long misfortune, he continued to be swayed by faction and intrigue. The cause of the Pretender, though weakened, was yet kept alive; but his insignificance eventually left him so unsupported, that his death is not even recorded. [440]

In S. 1840 (A.D. 1784) the Chondawats reaped the harvest of their allegiance and made tic power thus acquired subservient to the indulgence of ancient animosities against the rival clan of Saktawat. Salumbar with his relatives Arjun Singh1395 of Kurabar and Partap Singh1396 of Amet, now ruled the councils, having the Sindi mercenaries under their leaders Chandan and Sadik at their command. Mustering therefore all the strength of their kin and clans, they resolved on the prosecution of the feud, and invested Bhindar, the castle of Mohkam the chief of the Saktawats, against which they placed their batteries.

Sangram Singh, a junior branch of the Saktawats, destined to play a conspicuous part in the future events of Mewar, was then rising into notice, and had just completed a feud with his rival the Purawat, whose abode, Lawa1397, he had carried by escalade; and now, determined to make a diversion in favour of his chief, he invaded the estate of Kurabar, engaged against Bhindar, and

was driving off the cattle, when Salim Singh the heir of Kurabar intercepted his retreat, and an action ensued in which Salim1398 was slain by the lance of Sangram. The afflicted father, on hearing the fate of his son, ‘threw the turban off his head,’ swearing never to replace it till he had tasted revenge. Feigning a misunderstanding with his own party he withdrew from the siege, taking the road to his estate, but suddenly abandoned it for Sheogarh, the residence of Lalji the father of Sangram. The castle of Sheogarh, placed amidst the mountains and deep forests of Chappan, was from its difficulty of access deemed secure against surprise; and here Sangram had placed the females and children of his family. To this point Arjun directed his revenge, and found Sheogarh destitute of defenders save the aged chief; but though seventy summers had whitened his head, he bravely met the storm, and fell in opposing the foe; when the children of Sangram were dragged [441] out and inhumanly butchered, and the widow1399 of Lalji ascended the pyre. This barbarity aggravated the hostility which separated the clans, and together with the minority of their prince and the yearly aggressions of the Mahrattas, accelerated the ruin of the country. But Bhim Singh, the Chondawat leader, was governed by insufferable vanity, and not only failed in respect to his prince, but offended the queen regent. He parcelled out the crown domain from Chitor to Tidaipur amongst the Sindi bands, and whilst his sovereign was obliged to borrow money to defray his marriage at Idar, this ungrateful noble had the audacity to disburse upwards of £100,000 on the marriage of his own daughter. Such conduct determined the royal mother to supplant the Chondawats, and calling in the Saktawats to her aid, she invested with power the chiefs of Bhindar and Lawa. Aware, however, that their isolated authority was insufficient to withstand their rivals, they looked abroad for support, and made an overture to Zalim Singh of Kotah, whose political and personal resentments to the Chondawats,

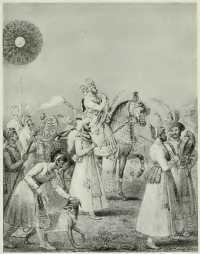

Maharaj Bhim Singh, Prince of Udaipur

as well as his connexion by marriage with their opponents, made him readily listen to it. With his friend the Mahratta, Lalaji Belal, he joined the Saktawats with a body of 10,000 men. It was determined to sacrifice the Salumbar chief, who took post in the ancient capital of Chitor, where the garrison was composed chiefly of Sindis, thus effacing his claim to his prince’s gratitude, whom he defied, while the pretender still had a party in the other principal fortress, Kumbhalmer.

Such was the state of things, when the ascendancy of Mahadaji Sindhia received a signal check from the combined forces of Marwar and Jaipur; and the battle of Lalsot, in which the Mahratta chief was completely defeated, was the signal for the Rajputs to resume their alienated territory1400. Nor was the Rana backward on the occasion, when there appeared a momentary gleam of the active virtue of past days. Maldas Mehta, was civil minister, with Mauji Rani as his deputy, both men of talent and energy. They first effected the reduction of Nimbahera and the smaller garrisons of Mahrattas in its vicinity, who from a sense of common danger assembled their detachments in Jawad, which was also invested. Sivaji Nana, the governor, capitulated, and was allowed to march out with his [442] effects. At the same time, the ‘sons of the black cloud1401’ assembling, drove the Mahrattas from Begun, Singoli, etc., and the districts on the plateau; while the Chondawats redeemed their ancient fief of Rampura, and thus for a while the whole territory was recovered. Elated by success, the united chiefs advanced to Chardu on the banks of the Rarkia, a streamlet dividing Mewar from Malwa, preparatory to further operations. Had these been confined to the maintenance of the places they had taken, and which had been withheld in violation of treaties, complete success might have crowned their efforts; but in including Nimbahera in their capture they drew upon them the energetic Ahalya Bai, the regent-queen of the Holkar State, who unluckily for them was at hand and who coalesced with Sindhia’s partisans to check

this reaction of the Rajputs. Tulaji Sindhia and Sri Bhai, with five thousand horse, were ordered to support the discomfited Siva Nana, who had taken refuge in Mandasor, where he rallied all the garrisons whom the Rajputs had unwisely permitted to capitulate.

On Tuesday, the 4th of Magh S. 18441402, the Rana’s troops were surprised and defeated with great slaughter, the minister slain, the chiefs of Kanor and Sadri with many others severely wounded, and the latter made prisoner1403. The newly made conquests were all rapidly lost, with the exception of Jawad, which was gallantly maintained for a month by Dip Oland, who, with his guns and rockets, effected a passage through the Mahrattas, and retired with his garrison to Mandalgarh. Thus terminated an enterprise which might have yielded far different results but for a misplaced security. All the chiefs and clans were united in this patriotic struggle except the Chondawats, against whom the queen-mother and the new minister, Somji, had much difficulty to contend for the establishment of the minor’s authority. At length overtures were made to Salumbar, when the fair Rampiyari was employed to conciliate the obdurate chief, who condescended to make his appearance at Udaipur and to pay his respects to the prince. He pretended to enter into the views of the minister and to coalesce in his plans; but this was only a web to ensnare his victim, whose talent had diminished his authority, and was a bar to the prosecution of [443] his ambitious views. Somji was seated in his bureau when Arjun Singh of Kurabar and Sardar Singh1404 of Badesar entered, and the latter, as he demanded how he dared to resume his fief, plunged his dagger into the minister’s breast. The Rana was passing the day at one of the villas in the valley called the Sahelia Bari, ‘the garden of nymphs,’ attended by Jeth Singh of Badnor, when the brothers1405 of the

minister suddenly rushed into the presence to claim protection against the murderers. They were followed by Arjun of Kurabar, who had the audacity to present himself before his sovereign with his hands yet stained with the blood of Somji. The Rana., unable to punish the insolent chief, branding him as a traitor, bade him begone; when the whole of the actors in this nefarious scene, with their leader Salumbar, returned to Chi tor. Sheodas and Satidas, brothers to the murdered minister, were appointed to succeed him, and with the Saktawats fought several actions against the rebels, and gained one decisive battle at Akola, in which Arlon of Kurabar commanded. This was soon balanced by the defeat of the Saktawats at Kheroda. Every triumph was attended with ruin to the country. The agriculturist, never certain of the fruits of his labour, abandoned his fields, and at length his country; mechanical industry found no recompense, and commerce was at the mercy of unlicensed spoliation. In a very few years Mewar lost half her population, her lands lay waste, her mines were unworked, and her looms, which formerly supplied all around, forsaken. The prince partook of the general penury; instead of protecting, he required protection; the bonds which united him with his subjects were snapped, and each individual or petty community provided for itself that defence which he could not give. Hence arose a train of evils: every cultivator, whether fiscal or feudal, sought out a patron, and [444] entered into engagements as the price of protection. Hence every Rajput who had a horse and lance, had his clients; and not a camel-load of merchandise could pass the abode of one of these cavaliers without paying fees. The effects of such disorder

were felt long after the cause ceased to exist, and claims difficult to adjust arose out of these licentious times, for the having prescriptive right was deemed sufficient to authorize their continuance1406. Here were displayed the effects of a feudal association, where the powers of government were enfeebled. These feuds alone were sufficient to ruin the country; but when to such internal ills shoals of Mahratta plunderers were added, no art is required to describe the consequences.

The Rana and his advisers at length determined to call in Sindhia to expel the rebellious Chondawats from the ancient capital; a step mainly prompted by Zalim Singh (now Regent of Kotah), who with the Rana’s ministers was deputed to the Mahratta chieftain, then enjoying himself at the sacred lake of Pushkar1407. Since the overthrow of Lalsot he had reorganized his brigades under the celebrated De Boigne1408, through whose conduct he had redeemed his lost influence in Rajputana by the battles of Merta and Patan, in which the brave Rathors, after acts of the most devoted gallantry, were completely overthrown. Sindhia’s plans coincided entirely with the object of the deputation, and he readily acquiesced in the Rana’s desire. This event introduced on the political stage some of the most celebrated men of that day, whose actions offer a fair picture of manners, and may justify our entering a little into details1409.

Zalim Singh had for some years become regent of Kotah, and though to maintain himself in power, and the State he controlled in an attitude to compel the respect of surrounding foes, was no slight task, yet he found the field too contracted for his ambition, and his secret views had long been directed to permanent influence in Mewar. His skill in reading character convinced him that the Rana would be no

bar to his wishes, the attainment of which, by giving him the combined resources of Haraoti and Mewar, would bestow the lead in Rajasthan. The Jaipur court he disregarded, whose effeminate army he had himself defeated single-handed [445] with the Kotah troops, and the influence he established amongst the leading chiefs of Marwar held out no fear of counteraction from that quarter. The stake was high, the game sure, and success would have opened a field to his genius which might have entirely altered the fate of Hindustan; but one false move was irretrievable, and instead of becoming the arbitrator of India, he left only the reputation of being the Nestor of Rajputana.

The restriction of the Rana’s power was the cloak under which he disguised all his operations, and it might have been well for the country had his plans succeeded to their full extent. To re-establish the Rana’s authority, and to pay the charges of the reduction of Chitor, he determined that the rebels chiefly should furnish the means, and that from them and the fiscal lands, mostly in their hands, sixty-four lakhs should be levied, of which three-fifths should be appropriated to Sindhia, and the remainder to replenish the Rana’s treasury. Preliminaries being thus arranged, Zalim was furnished with a strong corps under Ambaji Inglia; while Sindhia followed, hanging on the Marwar frontier, to realize the contributions of that State. Zalim Singh and Ambaji moved towards Chitor, levying front the estates of those obnoxious to Zalim’s views. Hamirgarh, whose chief, Dhiraj Singh, a man of talent and courage, was the principal adviser of Bhim Singh, the Salumbar chief, was besieged, and stood several assaults during six weeks’ vigorous operations, when the destruction of the springs of the wells from the concussion of the guns compelled its surrender, and the estate was sequestrated. The force continued their progress, and after a trifling altercation at Basai, a Chondawat fief, also taken, they took up a position at Chitor, and were soon after joined by the main body under Sindhia.

Zalim, to gratify Mahadaji’s vanity, who was desirous of a visit from the Rana, which even the Peshwa considered an honour, proceeded to Udaipur to effect this object; when the. Rana, placing himself under his guidance, marched for this purpose, and was met at the Tiger Mnimt, within a few miles of his capital, by Sindhia,

who received the Rana, and escorted him to the besieging army. But in this short interval, Ambaji, who remained with the army at Chitor, intrigued with the rebel Chondawat to supplant the predominant influence of his friend Zalim Singh, and seized the opportunity of his absence to counteract him, by [446] communicating his plans to Salumbar; aware that, unless he broke with Zalim, he could only hope to play a secondary part under him. Though the ulterior views of Zalim were kept to his own breast, they could not escape the penetration of the crafty Mahratta; his very anxiety to hide them-furnished Ambaji with the means of detection. Had Zalim possessed an equal share of meanness with his political antagonist, he might have extricated himself from the snare; but once overreached, he preferred sinking to grasping at an unworthy support. Bhim Singh (Salumbar) privately negotiated with Ambaji the surrender of Chitor, engaging to humble himself before the Rana, and to pay a contribution of twenty lakhs, levied on the clans, provided Zalim Singh was ordered to retire. This suggestion, apparently founded on the rebellious chief’s antipathy to Zalim, but in reality prompted by Ambaji, ensured the approbation, as it suited the views, of all-parties, but especially Sindhia, who was desirous of repairing to Poona. Zalim, the sole obstacle to this arrangement, furnished to his enemies the means of escape from the dilemma, and lost the opportunity of realizing his long-cherished scheme of wielding the united resources of Mewar and Haraoti. Zalim had always preserved a strict amity with Ambaji wherever their interests did not clash, and his regard had the cement of gratitude to the Mahratta, whose father Trimbakji had saved Zalim’s life and procured his liberty, when left wounded and a prisoner at the battle of Ujjain. On Zalim’s return with the Rana, Ambaji touched on the terms of Bhim Singh’s surrender, hinting that Zalim’s presence was the sole obstacle to this desirable result; who, the more to mask his views, which any expressed reluctance to the measure might expose, went beyond probability in asseverations of readiness to be no bar to such arrangement, even so far as to affirm that, besides being tired of the business from the heavy expense it entailed on him, he had his prince’s wish for his return to Kotah. There is one ingredient in Zalim’s character, which has never been totally merged in the vices acquired from the tortuous policy of a long life, and which in the vigour

of youth had full sway – namely, pride, one of the few virtues left to the Rajput, defrauded of many others by long oppression. But Zalim’s pride was legitimate, being allied to honour, and it has retained him an evident superiority through all the mazes of ambition. Ambaji skilfully availed himself of this defect in his friend’s political character. “A pretty [447] story, indeed!you tell this to me! it might find credit with those who did not know you.” The sarcasm only plunged him deeper into asseveration. “Is it then really your wish to retire?” “Assuredly.” _ “Then,” retorted the crafty Ambaji, “your wish shall be gratified in a few minutes.” Giving him no time to retract, he called for his horse and galloped to Sindhia’s tent. Zalim relied on Sindhia not acceding to the proposition; or if he did, that the Rana, over whom he imagined he had complete influence, would oppose it. His hopes of Sindhia rested on a promise privately made to leave troops under his authority for the restoration of order in Mewar; and a yet stronger claim, the knowledge that without Zalim he could not realize the stipulated sums for the expulsion of the Chondawat from Chitor. Ambaji had foreseen and prepared a remedy for these difficulties, and upon their being urged offered himself to advance the amount by bills on the Deccan. This argument was irresistible; money, and the consequent prosecution of his journey to Poona, being attained, Sindhia’s engagements with Zalim and the Rana ceased to be a matter of importance. He nominated Ambaji his lieutenant, with the command of a large force, by whose aid he would reimburse himself for the sums thus advanced. Having carried his object with Sindhia, Ambaji proceeded direct from his tent to that of the Rana’s ministers, Sheodas and Satidas, with whom, by the promise of co-operation in their views, and perfect subserviency to the Rana’s interests, he was alike successful. Ambaji, with the rapidity necessary to ensure success, having in a few hours accomplished his purpose, hastened back to Zalim, to acquaint him that his wish to retire had met with general acquiescence; and so well did he manage, that the Rana’s mace-bearer arrived at the same moment to announce that the khilat of leave awaited his acceptance. Zalim being thus outwitted, the Salumbar chief descended from Chitor, and touched the Rana’s feet. Sindhia pursued his march to the Deccan, and Ambaji was left sole arbiter of Mewar. The Saktawats maintained the lead at court,

and were not backward in consigning the estates of their rivals to the incubus now settled on the country: while the mortified Zalim, on his retreat, recorded his expenses, to be produced on some fitting occasion.

Ambaji remained eight years in Mewar, reaping its revenues and amassing those hoards of wealth which subsequently gave him the lead in Hindustan, and enabled him nearly to assert his independence. Yet, although he accumulated [448] £2,000,000 sterling from her soil1410, exacting one-half of the produce of agricultural industry, the suppression of feuds and exterior aggressions gave to Mewar a degree of tranquillity and happiness to which she had long been a stranger. The instructions delivered to Ambaji were

1. The entire restoration of the Rana’s authority and resumption of the crown-lands from rebellious chiefs and mercenary Sindis.

2. The expulsion of the pretender from Kumbhalmer.

3. The recovery of Godwar from the Raja of Marwar.

4. To settle the Bundi feud for the murder of Rana Arsi.

A schedule (pandhri)1411 for the twenty lakhs stipulated was made and levied; twelve from the Chondawat estates and eight from the Saktawats; and the sum of sixty lakhs was awarded, besides the expense of Ambaji’s army, when the other specified objects should be attained. Within two years the pretender was expelled Kumbhalmer, Jahazpur was recovered from a rebellious Ranawat, and the crown-lands1412 were redeemed from

the nobles; the personal domain of the Rana, agricultural and commercial, still realized nearly fifty lakhs of rupees. After these services, though Godwar was still unredeemed, the Bundi feud unappeased, and the lands mortgaged to the Mahrattas were not restored, Ambaji assumed the title of Subahdar of Mewar, and identified himself with the parties of the day. Yet so long as he personally upheld the interests of the Rana, his memory is done justice to, notwithstanding he never conformed to the strict letter of his engagements. The Rana’s ministers, fearing lest their brother’s fate should be theirs in the event of the Chondawats again attaining power, and deeming their own and their sovereign’s security dependent on Ambaji’s presence, made a subsidiary engagement with him, and lands to the amount of 75,000 rupees monthly, or eight lakhs annually, were appropriated for his force; but so completely were the resources of the [449] country diverted from their honest use, that when, in S. 1851, a marriage was negotiated between the Rana’s sister and the prince of Jaipur, the Rana was obliged to borrow £50,000 from the Mahratta commander to purchase the nuptial presents. The following year was marked by a triple event – the death of the queen-mother, the birth of a son and heir to the Rana, and the bursting of the embankment of the lake, which swept away a third of the city and a third of its inhabitants. Superstition attributed this catastrophe to the Rana’s impiety, in establishing a new festival1413 to Gauri, the Isis of Rajasthan.

Ambaji, who was this year nominated by Sindhia his viceroy in Hindustan, left Ganesh Pant as his lieutenant in Mewar, with whom acted the Rana’s officers, Sawai and Shirji Mehta1414; who applied themselves to make the most of their ephemeral power with so rapacious a spirit, that Ambaji was compelled to displace Ganesh Pant and appoint the celebrated Rae Chand. To him they would not yield, and each party formed a nucleus for disorder and misrule. It would be uninteresting

and nauseating to the reader to carry him through all the scenes of villainy which gradually desolated this country; for whose spoil pilfering Mahrattas, savage Rohillas, and adventurous Franks were all let loose. The now humbled Chondawats, many of whose fiefs were confiscated, took to horse, and in conjunction with lawless Sindis scoured the country. Their estates were attacked, Kurabar was taken, and batteries were placed against Salumbar, whence the Sindis fled and found refuge in Deogarh. In this exigence, the Chondawats determined to send an envoy to Ambaji, who was then engaged in the siege of Datia; and Ajit Singh, since prominent in the intrigues of Mewar, was the organ of his clan on this occasion. For the sum of ten lakhs the avaricious Mahratta agreed to recall his deputy from Mewar1415, to renounce Sheodas and the Saktawats, and lend his support to the Chondawats. The Salumbar chief again took the lead at court, and with Agarji Mehta1416 as minister, the Saktawats [450]

were attacked, the stipulated ten lakhs raised from their estates, and two fiefs of note, Hintha and Semari, confiscated. [451]

The death of Mahadaji Sindhia1417, and the accession of his nephew Daulatrao, his murder of the Shenvi Brahmans, and his quarrels with the Bais (‘princesses,’ wives of the deceased Sindhia), all occurred at this time, and materially influenced the events in Mewar. The power of Airtbaji as Subahdar of Hindustan was strengthened by the minority of Sindhia, although contested by Lakwa and the Bais, supported by the Khichi prince, Durjan Sal, and the Datia Raja, who fought and died for the princesses. Lakwa wrote to the Rana to throw off Ambaji’s yoke and expel his lieutenant; while Ambaji commanded his deputy to eject the Shenvi1418 Brahmans,

supporters of Lakwa, from all the lands in Mewar. To this end Ganesh Pant called on the Rana’s ministers and chiefs, who, consulting thereon, determined to play a deep game; and while they apparently acquiesced in the schemes of Ganesh, they wrote the Shenvis to advance from Jawad and attack him, promising them support. They met at Sawa; Nana was defeated with the loss of his guns, and retired on Chitor. With a feint of support, the Chondawats made him again call in his garrison and try another battle, which he also lost and fled to Hamirgarh; then, uniting with his enemies, they invested the place with 15,000 men. Nana bravely maintained himself, making many sallies, in one of which both the sons of Dhiraj Singh, the chief of Hamirgarh, were slain. Shortly after, Nana was relieved by some battalions of the new raised regulars sent by Ambaji under Gulab Rao Kadam, upon which he commenced his retreat on Ajmer. At Musamusi he was forced to action, and success had nearly crowned the efforts of the clans, when a horseman, endeavouring to secure a mare, calling out, [452] “Bhagi! bhagi!” “She flies! she flies!” the word spread, while those who caught her, exclaiming “Milgayi! milgayi!” “She is taken!” but equally significant with ‘going over’ to the enemy, caused a general panic, and the Chondawats, on the verge of victory, disgraced themselves, broke and fled. Several were slain, among whom was the Sindi leader Chandan. Shahpura opened its gates to the fugitives led by the Goliath of the host, the chief of Deogarh1419. It was an occasion not to be lost by the bards of the rival clan, and many a ribald stanza records this day’s disgrace. Ambaji’s lieutenant, however, was so roughly handled that several chiefs redeemed their estates, and the Rana much of the fist, from Mahratta control.

Mewar now became the arena on which the rival satraps Ambaji and Lakwa, contested the

exalted office of Sindhia’s lieutenancy in Hindustan. Lakwa was joined by all the chiefs of Mewar, his cause being their own; and Hamirgarh, still held by Nana’s party, Was reinvested. Two thousand shot had made a practicable breach, when Bala Rao Inglia, Bapu Sindhia, Jaswant Rao Sindhia, a brigade under the European ‘Mutta field1420,’ with the auxiliary battalions of Zalim Singh of Kotah, the whole under the command of Ambaji’s son, arrived to relieve the lieutenant. Lakwa raised the siege, and took post with his allies under the walls of Chitor; whilst the besieged left the untenable Hamirgarh, and joined the relief at Gosunda. The rival armies were separated only by the Berach river, On whose banks they raised batteries and cannonaded each other, when a dispute arose in the victor camp regarding the pay of the troops, between Bala Rao (brother of Ambaji) and Nana, and the latter withdrew and retreated to Sanganer. Thus disunited, it might have been expected that these congregated masses would have dissolved, or fallen upon each other, when the Rajputs might have given the coup de grâce to the survivors; but they were Mahrattas, and their politics were too complicated to end in simple strife: almost all the actors in these scenes lived to contest with, and be humiliated by, the British.

The defection of Nana equalized the parties; but Bala Rao, never partial to fighting, opportunely recollected a debt of gratitude to Lakwa, to whose clemency he owed his life when taken by storm in Gugal Chapra. He also wanted money [453] to pay his force, which a private overture to Lakwa secured. They met, and Bala Rao retired boasting of his gratitude, to which, and the defection of Nana, soon followed by that of Bapu Sindhia, the salvation of Lakwa was attributed. Sutherland1421 with a brigade was detached by Ambaji to aid Nana: but a dispute depriving him of this reinforcement, he called in a partisan of more celebrity, the brave George Thomas1422. Ambaji’s

lieutenant and Lakwa were once more equal foes, and the Rana, his chiefs and subjects being distracted between these conflicting bands, whose leaders alternately paid their respects to him, were glad to obtain a little repose by espousing the cause of either combatant, whose armies during the monsoon encamped for six weeks within sight of each other1423.

Durjan Sal (Khichi), with the nobles of Mewar, hovered round Nana’s camp with five thousand horse to cut off his supplies; but Thomas escorted the convoys from Shahpura with his regulars, and defied all their efforts. Thomas at length advanced his batteries against Lakwa, on whose position a general assault was about taking place, when a tremendous storm, with torrents of rain which filled the stream, cut off his batteries from the main body, burst the gates of Shahpura, his point d’appui, and laid the town in ruins1424. Lakwa seized the moment, and with the Mewar chiefs stormed and carried the isolated batteries, capturing fifteen pieces of cannon; and the Shahpura Raja, threatened at once by his brother-nobles and the vengeance of heaven, refused further provision to Nana, who was compelled to abandon his position and retreat to Sanganer. The discomfited lieutenant vowed vengeance against the estates of the Mewar chieftains, and after the rains, being reinforced by Ambaji, again took the field. Then commenced a scene of carnage, pillage, and individual defence. The whole of the Chondawat estates under the Aravalli range were laid waste, their castles assaulted, some taken and destroyed, and heavy sums levied on all. Thomas besieged Deogarh and Amet, and both fought and paid. Kasital and Lasani were captured, and the latter razed for its gallant resistance. Thus they were proceeding in the work of destruction, when Ambaji [454] was dispossessed of the government of Hindustan, to which Lakwa was nominated1425, and Nana was compelled to surrender all the fortresses and towns he held in Mewar.

From this period must be dated the pretensions of Sindhia to consider Mewar as tributary to him. We have traced the rise of the Mahrattas, and the progress of their baneful influence in Mewar. The abstractions of territory from S. 1826 to 1831 [A.D. 1769–74], as pledges for contributions, satisfied their avarice till 1848 [A.D. 1791], when the Salumbar rebellion brought the great Sindhia to Chitor, leaving Ambaji as his lieutenant, with a subsidiary force, to recover the Rana’s lost possessions. We have related how these conditions were fulfilled; how Ambaji, inflated with the wealth of Mewar, assumed almost regal dignity in Hindustan, assigning the devoted land to be governed by his deputies, whose contest with other aspirants made this unhappy region the stage for constant struggles for supremacy; and while the secret policy of Zalim Singh stimulated the Saktawats to cling to Ambaji, the Chondawats gave their influence and interest to his rival Lakwa. The unhappy Rana and the peasantry paid for this rivalry; while Sindhia, whose power was now in its zenith, fastened one of his desultory armies on Mewar, in contravention of former treaties, without any definite views, or even instructions to its commander. It was enough that a large body should supply itself without assailing him for prey, and whose services were available when required.

Lakwa, the new viceroy, marched to Mewar: Agarji Mehta was appointed minister to the Rana, and the Chondawats again came into power. For the sum of six lakhs Lakwa dispossessed the Shahpura of Jahazpur, for the liquidation of which thirty-six of its towns were mortgaged. Zalim Singh, who had long been manoeuvring to obtain Jahazpur, administered to the necessities of the Mahratta, paid the note of hand, and took possession of the city and its villages. A contribution of twenty-four lakhs was imposed throughout the country, and levied by force of arms, after which first act of the new viceroy he quitted Mewar for Jaipur, leaving Jaswant Rao Bhao as his deputy. Mauji Rain, the deputy of Agarji (the Rana’s minister), determined to adopt the European mode of discipline, now become general amongst all the native powers of India. But when the chiefs were [455] called upon to contribute to the support of mercenary regulars and a field-artillery, they evinced their patriotism by confining this zealous minister. Satidas was

once more placed in power, and his brother Sheodas recalled from Kotah, whither he had fled from the Chondawats, who now appropriated to themselves the most valuable portions of the liana’s personal domain.

The battle of Indore1426, in A.D. 1802, where at least 150,000 men assembled to dispute the claim to predatory empire, wrested the ascendancy from Holkar, who lost his guns, equipage, and capital, from which he fled to Mewar, pursued by Sindhia’s victorious army led by Sadasheo and Bala Rao. In his flight he plundered Ratlam, and passing Bhindar, the castle of the Saktawat chief, he demanded a contribution, from which and his meditated visit to Udaipur, the Rana and his vassal were saved by the activity of the pursuit. Failing in these objects, Holkar retreated on Nathdwara, the celebrated shrine of the Hindu Apollo1427. It was here this active soldier first showed symptoms of mental derangement. He upbraided Krishna, while prostrate before his image, for the loss of his victory; and levied three lakhs of rupees on the priests and inhabitants, several of whom he carried to his camp as hostages for the payment. The portal (dwara) of the god (North) proving no bar either to Turk or equally impious Mahratta, Damodarji, the high priest, removed the god of Vraj from his pedestal and sent him with his establishment to Udaipur for protection. The Chauhan chief of Kotharia (one of the sixteen nobles), in whose estate was the sacred Pane, undertook the duty, and with twenty horsemen, his vassals, escorted the shepherd god by intricate passes to the capital. On his return he was intercepted by a band of Holkar’s troops, who insultingly desired the surrender of their horses. But the descendant of the illustrious Prithiraj preferred death to dishonour: dismounting, he hamstrung his steed, commanding his vassals to follow his example; and sword in hand courted his fate in the unequal conflict, in which he fell, with most of his gallant retainers. There are many such isolated exploits in the records of this eventful period, of which the Chauhans of Kotharia had their full share. Spoil, from whatever source, being welcome to these depredators, Nathdwara1428 remained long abandoned; and Apollo, after

six months’ residence at Udaipur, finding [456] insufficient protection, took another flight to the mountains of Ghasyar, where the high priest threw up fortifications for his defence; and spiritual thunders being disregarded, the pontiff henceforth buckled on the armour of flesh, and at the head of four hundred cavaliers with lance and shield, visited the minor shrines in his extensive diocese.

To return to Holkar. He pursued his route by Banera and Shahpura, levying from both, to Ajmer, where he distributed a portion of the offerings of the followers of Krishna amongst the priests of Muhammad at the mosque of Khwaja Pir. Thence he proceeded towards Jaipur. Sindhia’s leaders on reaching Mewar renounced the pursuit, and Udaipur was cursed with their presence, when three lakhs of rupees were extorted from the unfortunate Rana, raised by the sale of household effects and the jewels of the females of his family. Jaswant Rao Bhao, the Subandar of Mewar, had prepared another schedule (pandhri), which he left with Tantia, his deputy, to realize. Then followed the usual scene of conflict – the attack of the chieftain’s estates, distraining of the husbandman, seizure of his cattle, and his captivity for ransom, or his exile.

The celebrated Lakwa, disgraced by his prince, died at this time1429 in sanctuary at Salurnbar; and Bala Rao, brother to Ambaji, returned, and was joined by the Saktawats and the minister Satidas, who expelled the Chondawats for their control over the prince. Zalim Singh, in furtherance of his schemes and through hatred of the Chondawats, united himself to this faction, and Devi Chand, minister to the Rana, set up by the Chondawats, was made prisoner. Bala Rao levied and destroyed their estates with unexampled ferocity, which produced a bold attempt at deliverance. The Chondawat leaders assembled at the Chaugan (the Champ de Mars) to consult on their safety. The insolent Mahratta had preceded them to the palace, demanding the surrender of the minister’s deputy, Mauji Ram. The Rana indignantly refused them – the Mahratta importuned, threatened, and at length commanded his troops to advance, to the palace, when the intrepid minister pinioned the audacious plunderers, and secured his adherents (including their old enemy, Nana Ganesh), Jamalkar, and Uda Kunwar. The latter, a

notorious villain, had an elephant’s chain put round his neck, while Bala Rao was confined in a bath. The [457] leaders thus arrested, the Chondawats sallied forth and attacked their camp in the valley, which surrendered; though the regulars under Hearsey1430 retreated in a hollow square, and reached Gadarmala in safety. Zalim Singh determined to liberate his friend Bala Rao from peril; and aided by the Saktawats under the chiefs of Bhindar and Lawa, advanced to the Chaija Pass, one of the defiles leading to the capital. Had the Rana put these chiefs to instant death, he would have been justified, although he would have incurred the resentment of the whole Mahratta nation. Instead of this, he put himself at the head of a motley levy of six thousand Sindis, Arabs, and Gosains, with the brave Jai Singh and a band of his gallant Khichis, ever ready to poise the lance against a Mahratta. They defended the pass for five days against a powerful artillery. At length the Rana was compelled to liberate Bala Rao, and Zalim Singh obtained by this interference possession of the fortress and entire district of Jahazpur. A schedule of war contribution, the usual finale to these events, followed Bala’s liberation, and no means were left untried to realize the exaction, before Holkar, then approaching, could contest the spoil.

This chief, having recruited his shattered forces, again left the south1431. Bhindar felt his resentment for non-compliance with his demands on his retreat after the battle of Indore; the town was nearly destroyed, but spared for two lakhs of rupees, for the payment of which villages were assigned. Thence he repaired to Udaipur, being met by Ajit Singh, the Rana’s ambassador, when the enormous sum of forty lakhs, or £500,000, was demanded from the country, of which one-third was commanded to be instantly forthcoming. The palace was denuded of everything which could be converted into gold; the females were deprived of every article of luxury and comfort: by which, with contributions levied on the city, twelve lakhs were

obtained; while hostages from the household of the Rana and chief citizens were delivered as security for the remainder, and immured in the Mahratta camp. Holkar then visited the Rana. Lawa and Badnor were attacked, taken, and restored on large payments. Deogarh alone was mulcted four and a half lakhs. Having devastated Mewar during eight months, Holkar [458] marched to Hindustan1432, Ajit Singh accompanying him as the Rana’s representative; while Bala Ram Seth was left to levy the balance of the forty lakhs. Holkar had reached Shahpura when Sindhia entered Mewar, and their camps formed a junction to allow the leaders to organize their mutual plans of hostility to the British Government. These chieftains, in their efforts to cope with the British power, had been completely .humiliated, and their resources broken. But Rajasthan was made to pay the penalty of British success, which riveted her chains, and it would be but honest, now we have the power, to diminish that penalty.

The rainy season of A.D. 1805 found Sindhia and Holkar encamped in the plains of Badnor, desirous, but afraid, to seek revenge in the renewal of war. Deprived of all power in Hindustan, and of the choicest territory north and south of the Nerbudda, with numerous discontented armies now let loose on these devoted countries, their passions inflamed by defeat, and blind to every sentiment of humanity, they had no alternative to pacify the soldiery and replenish their own ruined resources but indiscriminate pillage. It would require a pen powerful as the pencil of Salvator Rosa to paint the horrors which filled up the succeeding ten years, to which the author was an eye-witness, destined to follow in the train of rapine, and to view in the traces of Mahratta camps1433 the desolation

and political annihilation of all the central States of India1434, several of which aided the British in their early struggle for dominion, but were now allowed to fall without a helping hand, the scapegoats of our successes. Peace between the Mahrattas and British was, however, doubtful, as Sindhia made the restoration of the rich provinces of Gohad and Gwalior a sine qua non: and unhappily for their legitimate ruler, who [459] had been inducted into the seat of his forefathers, a Governor-General (Lord Cornwallis) of ancient renown, but in the decline of life, with views totally unsuited to the times, abandoned our allies, and renounced all for peace, sending an ambassador1435 to Sindhia to reunite the bonds of perpetual friendship.’

The Mahratta leaders were anxious, if the war should be renewed, to shelter their families and valuables in the strongholds of Mewar, and their respective camps became the rendezvous of the rival factions. Sardar Singh, the organ of the Chondawats, represented the Rana at Sindhia’s court, at the head of whose councils Ambaji had just been placed1436. His rancour to the Rana was implacable, from the support given in self-defence to his political antagonist, Lakwa, and he agitated the partition of Mewar amongst the great Mahratta leaders. But whilst his baneful influence was preparing this result, the credit of Sangram Saktawat with Holkar counteracted it. It would be unfair and ungallant not to record that a fair suitor, the Baiza Bai1437, Sindhia’s wife, powerfully

contributed to the Rana’s preservation on this occasion. This lady, the daughter of the notorious Sarji Rao, had unbounded power over Sindhia. Her sympathies were awakened on behalf of the supreme head of the Rajput nation, of which blood she had to boast, though she was now connected with the Mahrattas. Even the hostile clans stifled their animosities on this occasion, and Sardar Singh Chondawat left Sindhia’s camp to join his rival Sangram with Holkar, and aided by the upright Kishandas Paneholi, united in their remonstrances, asking Holkar if he had given his consent to sell Mewar to Ambaji. Touched by the picture of the Rana’s and their country’s distresses, Holkar swore it should not be; advised unity amongst themselves, and caused the representatives of the rival clans ‘to eat opium together.’ Nor did he stop here, but with the envoys repaired to Sindhia’s tents, descanted on the Rana’s high descent, ‘the master of their master’s master1438,’ urging that it did not become them to overwhelm him, and that they should even renounce the mortgaged lands which their fathers had too long unjustly held, himself setting the example by the restitution of [460] Nimbahera. To strengthen his argument, he expatiated with Sindhia on the policy of conciliating the Rana, whose strongholds might be available in the event of a renewal of hostilities with the British. Sindhia appeared a convert to his views, and retained the envoys in his camp. The Mahratta camps were twenty miles apart, and incessant torrents of rain had for some days prevented all intercourse. In this interim, Holkar received intelligence that Bhairon Baklish, as envoy from the Rana, was in Lord Lake’s camp negotiating for the aid of British troops, then at Tonk, to drive the Mahrattas from Mewar. The incensed Holkar sent for the Rana’s ambassadors, and assailed them with a torrent of reproach; accusing them of treachery, he threw the newspaper containing the information at Kishandas, asking if that were the way in which the Mewaris kept faith with him? “I cared not to break with Sindhia in support of your master, and while combating the Farangis (Franks), when all the Hindus should be

as brothers, your sovereign the Rana, who boasts of not acknowledging the supremacy of Delhi, is the first to enter into arms with them. Was it for this I prevented Ambaji being fastened on you?” Kishandas here interrupted and attempted to pacify him, when Alikar Tantia, Holkar’s minister, stopped him short, observing to his prince,” You see the faith of these Rangras1439; they would disunite you and Sindhia, and ruin both. Shake them off: be reconciled to Sindhia, dismiss Sarji Rao, and let Ambaji be Subandar of Mewar, or I will leave you and take Sindhia into Malwa.” The other councillors, with the exception of Bhao Bhaskar, seconded this advice: Sarji Rao was dismissed; and Holkar proceeded northward, where he was encountered and pursued to the Panjab by the British under the intrepid and enterprising Lake, who dictated terms to the Mahratta at the altars of Alexander1440.

Holkar had the generosity to stipulate, before his departure from Mewar, for the security of the Rana and his country, telling Sindhia he should hold him personally amenable to him if Ambaji were permitted to violate his guarantee. But in his misfortunes this threat was disregarded, and a contribution of sixteen lakhs was levied immediately on Mewar; Sadasheo Rao, with Baptiste’s1441 brigade, was detached from the camp in June 1806, for the double purpose of levying it, and driving from [461] Udaipur a detachment of the Jaipur prince’s troops, bringing proposals and preliminary presents for this prince’s marriage with the Rana’s daughter.

It would be imagined that the miseries of Rana Bhim were not susceptible of aggravation, and that fortune had done her worst to humble him; but his

pride as a sovereign and his feelings as a parent were destined to be yet more deeply wounded. The Jaipur cortege had encamped near the capital, to the number of three thousand men, while the Rana’s acknowledgments of acceptance were dispatched, and had reached Shahpura. But Raja Man of Marwar also advanced pretensions, founded on the princess having been actually betrothed to his predecessor; and urging that the throne of Marwar, and not the individual occupant, was the object, he vowed resentment and opposition if his claims were disregarded. These were suggested, it is said, by his nobles to cloak their own views; and promoted by the Chondawats (then ifs favour with the Rana), whose organ, Ajit, was bribed to further them, contrary to the decided wishes of their prince.

Krishna Kunwari (the Virgin Krishna) was the name of the lovely object, the rivalry for whose hand assembled under the banners of her suitors (Jagat Singh of Jaipur and Raja Man of Marwar), not only their native chivalry, but all the predatory powers of India; and who, like Helen of old, involved in destruction her own and the rival houses. Sindhia having been denied a pecuniary demand by Jaipur, not only opposed the nuptials, but aided the claims of Raja Man, by demanding of the Rana the dismissal of the Jaipur embassy: which being refused, he advanced his brigades and batteries, and after a fruitless resistance, in which the Jaipur troops joined, forced the pass, threw a corps of eight thousand men into the valley, and following in person, encamped within cannon-range of the city. The Rana had now no alternative but to dismiss the nuptial cortege, and agree to whatever was demanded. Sindhia remained a month in the valley, during which an interview took place between him and the Rana at the shrine of Eklinga1442. [462]

The heralds of Hymen being thus rudely repulsed and its symbols intercepted, the Jaipur prince prepared to avenge his insulted pride and disappointed hopes, and accordingly arrayed a force such as had not assembled since the empire was in its glory. Raja Man eagerly took up the gauntlet of his rival, and headed the swords of Marti.’ But dissension prevailed in Marwar, where rival claimants for the throne had divided the loyalty of the clans, introducing there also the influence of the Mahrattas. Raja Man, who had acquired the sceptre by party aid, was obliged to maintain himself by it, and to pursue the demoralizing policy of the period by ranging his vassals against each other. These nuptials gave the malcontents an opportunity to display their long-curbed resentments, and following the example of Mewar, they set up a pretender, whose interests were eagerly espoused, and whose standard was erected in the array of Jaipur; the prince at the head of 120,000 men advancing against his rival, who with less than half the number met him at Parbatsar, on their mutual frontier. The action was short, for while a heavy cannonade opened on either side, the majority of the Marwar nobles went over to the pretender. Raja Man turned his poniard against himself: but some chiefs yet faithful to him wrested the weapon from his hand, and conveyed him from the field. He was pursued to his capital, which was invested, besieged, and gallantly defended during six months. The town was at length taken and plundered, but the castle of Jodha ‘laughed a siege to scorn’; in time with the aid of finesse, the mighty host of Jaipur, which had consumed the forage of these arid plains for twenty miles around, began to crumble away; intrigue spread through every rank, and the siege ended in pusillanimity and flight. The Xerxes of Rajwara, the effeminate Kaebhwaha, alarmed at length for his personal safety, sent on the spoils of

Parbatsar and Jodhpur to his capital; but the brave nobles of Marwar, drawing the line between loyalty and patriotism, and determined that no trophy of Rathor degradation should be conveyed by the Kachhwahas from Marwar, attacked the cortege and redeemed the symbols of their disgrace. The colossal array of the invader was soon dismembered, and the ‘lion of the world’ (Jagat Singh), humbled and crestfallen, [463] skulked from the desert retreat of his rival, indebted to a partisan corps for safety and convoy to his capital, around whose walls the wretched remnants of this ill-starred confederacy long lagged in expectation of their pay, while the bones of their horses and the ashes of their riders whitened the plain, and rendered it a Golgotha1443.

By the aid of one of the most notorious villains India ever produced, the Nawab Amir Khan1444, the pretender’s party was treacherously annihilated. This man with his brigade of artillery and horse was amongst the most efficient of the foes of Raja Man; but the auri sacra fames not only made him desert the side on which he came for that of the Raja, but for a specific sum offer to rid him of the pretender and all his associates. Like Judas, he kissed whom he betrayed, took service with the pretender, and at the shrine of a saint of his own faith exchanged turbans with their leaders; and while the too credulous Rajput chieftains celebrated this acquisition to their party in the very sanctuary of hospitality, crowned by the dance and the song, the tents were cut down, and the victims thus enveloped, slaughtered in the midst of festivity by showers of grape.

Thus finished the under-plot; but another and more noble victim was demanded before discomfited ambition could repose, or the curtain drop on this eventful drama. Neither party

would relinquish his claim to the fair object of the war; and the torch of discord could be extinguished only in her blood. To the same ferocious Khan is attributed the unhallowed suggestion, as well as its compulsory execution. The scene was now changed from the desert castle of Jodha to the smiling valley of Udaipur, soon to be filled with funereal lamentation.

Krishna Kunwari Bai, the ‘Virgin Princess Krishna,’ was in her sixteenth year: her mother was of the Chawara race, the ancient kings of Anhilwara. Sprung from the noblest blood of Hind, she added beauty of face and person to an engaging demeanour, and was justly proclaimed the ‘flower of Rajasthan.’ When the Roman father pierced the bosom of the dishonoured Virginia, appeased virtue applauded the deed. When Iphigenia was led to the sacrificial altar, the salvation of her country yielded a noble consolation. The votive victim of Jephthah’s success had [464] the triumph of a father’s fame to sustain her resignation, and in the meekness of her sufferings we have the best parallel to the sacrifice of the lovely Krishna: though years have passed since the barbarous immolation, it is never related but with a faltering tongue and moistened eyes, albeit unused to the melting mood.’

The rapacious and bloodthirsty Pathan, covered with infamy, repaired to Udaipur, where he was joined by the pliant and subtle Ajit. Meek in his demeanour, unostentatious in his habits; despising honours, yet covetous of power, – religion, which he followed with the zeal of an ascetic, if it did not serve as a cloak, was at least no hindrance to an immeasurable ambition, in the attainment of which he would have sacrificed all but himself. ‘When the Pathan revealed his design, that either the princess should wed Raja Man, or by her death seal the peace of Rajwara, whatever arguments were used to point the alternative, the Rana was made to see no choice between consigning his beloved child to the Rathor prince, or witnessing the effects of a more extended dishonour from the vengeance of the Pathan, and the storm of I his palace by his licentious adherents – the fiat passed that Krishna Kunwari should die.

But the deed was left for women to accomplish – the hand of man refused it. The Rawala1445 of an Eastern prince is a world within itself; it is the labyrinth containing the strings that move

the puppets which alarm mankind. Here intrigue sits enthroned, and hence its influence radiates to the world, always at a loss to trace effects to their causes. Maharaja Daulat Singh1446, descended four generations ago from one common ancestor with the Rana, was first sounded ‘to save the honour of Udaipur’; but, horror-struck, he exclaimed, “Accursed the tongue that commands it! Dust on my allegiance, if thus to be preserved!” The Maharaja Jawandas, a natural brother, was then called upon; the dire necessity was explained, and it was urged that no common hand could be armed for the purpose. He accepted the poniard, but when in youthful loveliness Krishna appeared before him, the dagger fell from his hand, and he returned more wretched than the victim. The fatal purpose thus revealed, the shrieks of the frantic mother reverberated through the palace, as she implored mercy, or execrated the murderers of her child, who alone was resigned to her fate. But death was arrested, not averted. [465] To use the phrase of the narrator, “she was excused the steel – the cup was prepared,” – and prepared by female hands! As the messenger presented it in the name of her father, she bowed and drank it, sending up a prayer for his life and prosperity. The raving mother poured imprecations on his head, while the lovely victim, who shed not a tear, thus endeavoured to console her: “Why afflict yourself, my mother, at this shortening of the sorrows of life? I fear not to die! Am I not your daughter? Why should I fear death? We are marked out for sacrifice1447 from our birth; we scarcely enter the world but to be sent out again; let me thank my father that I have lived so long!1448” Thus she conversed till the nauseating

draught refused to assimilate with her blood. Again the bitter potion was prepared. She drained it off, and again it was rejected; but, as if to try the extreme of human fortitude, a third was administered; and, for the third time, Nature refused to aid the horrid purpose. It seemed as if the fabled charm, which guarded the life of the founder of her race1449, was inherited by the Virgin Krishna. But the blood-hounds, the Pathan and Ajit, were impatient till their victim was at rest; and cruelty, as if gathering strength from defeat, made another and a fatal attempt. A powerful opiate was presented – the kusumbha draught1450. She received it with a smile, wished the scene over, and drank it. The desires [466] of barbarity were accomplished. ‘She slept!1451’ a sleep from which she never awoke.

The wretched mother did not long survive her child; nature was exhausted in the ravings of despair; she refused food; and her remains in a few days followed those of her daughter to the funeral pyre.

Even the ferocious Khan, when the instrument of his infamy, Ajit, reported the issue, received him with contempt, and spurned him from his presence, tauntingly asking “if this were the boasted Rajput valour?” But the wily traitor had to encounter language far more bitter from his political adversary, whom he detested. Sangram Saktawat reached the capital only four days after tie catastrophe – a man in every respect the reverse of Ajit; audaciously brave, he neither feared the frown of his

sovereign nor the sword of his enemy. Without introduction he rushed into the presence, where he found seated the traitor Ajit. “Oh dastard! who hast thrown dust on the Sesodia race, whose blood which has flowed in purity through a hundred ages has now been defiled! this sin will check its course for ever; a blot so foul in our annals that no Sesodia1452 will ever again hold up his head! A sin to which no punishment were equal. But the end of our race is approaching! The line of Bappa Rawal is at an end! Heaven has ordained this, a signal of our destruction.” The Rana hid his face with his hands, when turning to Ajit, he exclaimed, “Thou stain on the Sesodia race, thou impure of Rajput blood, dust be on thy head as thou hast covered us all with shame. May you die childless, and your name die with you!1453 Why this indecent haste? Had the Pathan stormed the city? Had he attempted to violate the sanctity of the Rawala? And though be had, could you not die as Rajputs, like your ancestors? Was it thus they gained a name? Was it thus our race became renowned – thus they opposed the might of kings? Have you forgotten the Sakhas of Chi(or? But whom do I address – not Rajputs? Had the honour of your females been endangered, had you sacrificed them all and rushed sword in hand on the enemy, your name would have lived, and the Almighty would have secured the seed of Bappa Rawal. But to owe preservation [467] to this unhallowed deed! You did not even await the threatened danger. Fear seems to have deprived you of every faculty, or you might have spared the blood of Sriji1454, and if you did not scorn to owe your safety to deception, might have substituted some less noble victim! But the end of our race approaches!”

The traitor to manhood, his sovereign, and humanity, durst not reply. The brave Sangram is now dead, but the prophetic anathema has been fulfilled. Of ninety-five children, sons and daughters, but one son (the brother of Krishna)1455 is left to the Rana; and though his two remaining daughters have been recently married to the princes of Jaisalmer and Bikaner, the Salic law, which is in full force in these States,

precludes all honour through female descent. His hopes rest solely on the prince, Javana Singh1456, and though in the flower of youth and health, the marriage bed (albeit boasting no less than four young princesses) has been blessed with no progeny1457.

The elder brother of Javana1458 died two years ago. Had he lived he would have been Amra the Third. With regard to Ajit, the curse has been fully accomplished. Scarcely a month after, his wife and two sons were numbered with the dead; and the hoary traitor has since been wandering from shrine to shrine, performing penance and alms in expiation of his sins, yet unable to fling from him ambition; and with his beads in one hand, Rama! Rama! ever on his tongue, and subdued passion in his looks, his heart is deceitful as ever. Enough of him: let us exclaim with Sangram, “Dust on his head1459,” which all the waters of the Ganges could not purify from the blood of the virgin Krishna, but

rather would the multitudinous sea incarnadine. [468]

His coadjutor, Amir Khan, is now linked by treaties “in amity and unity of interests “

with the sovereigns of India; and though he has carried mourning into every house of Rajasthan, yet charity might hope forgiveness would be extended to him, could he cleanse himself from this deed of horror – ‘throwing this pearl away, richer than all his tribe!1460’ His career of rapine has terminated with the caresses of the blind goddess, and placed him on a pinnacle to which his sword would never have traced the path. Enjoying the most distinguished post amongst the foreign chieftains of Holkar’s State, having the regulars and park under his control, with large estates for their support, he added the epithet of traitor to his other titles, when the British Government, adopting the leading maxim of Asiatic policy, divide et impera, guaranteed to him the sovereignty of these districts on his abandoning the Mahrattas, disbanding his legions, and surrendering the park. But though he personally fulfilled not, nor could fulfil, one single stipulation, this man, whose services were not worth the pay of a single sepoy – who fled from his camp 1 unattended, and sought personal protection in that of the British commander – claimed and obtained the full price of our pledge, the sovereignty of about one-third of his master’s dominions; and the districts of Sironj, Tonk, Rampura, and Nimbahera, form the domain of the Nawab Amir Khan, etc., etc., etc.!! This was in the fitful fever of success, when our arms were everywhere triumphant. But were the viceroy of Hind to summon the forty tributaries1461 now covered by the aegis of British protection to a meeting, the murderer of Krishna would still occupy a place (though low) in this illustrious divan. Let us hope that his character being known, he would feel himself ill at ease; and let us dismiss him likewise in the words of Sangram, “Dust on his head! “

The mind sickens at the contemplation of these unvarying scenes of atrocity; but this unhappy State had yet to pass through two more lustres of aggravated sufferings (to which the author of these annals was an eye-witness) before their [469] termination, upon the alliance of Mewar with Britain. From the

period of the forcing of the passes, the dismissal of the Jaipur embassy by Sindhia, and the murder of Krishna Kunwari, the embassy of Britain was in the train of the Mahratta leader, a witness of the evils described – a most painful predicament – when the hand was stretched out for succour in vain, and the British flag waved in the centre of desolation, unable to afford protection. But this day of humiliation is past, thanks to the predatory hordes who goaded us on to their destruction; although the work was incomplete, a nucleus being imprudently left in Sindhia for the scattered particles again to form.

In the spring of 1800, when the embassy entered the once-fertile Mewar, from whose native wealth the monuments the pencil will portray were erected, nothing but ruin met the eye – deserted towns, roofless houses, and uncultured plains. Wherever the Mahratta encamped, annihilation was ensured; it was a habit; and twenty-four hours sufficed to give to the most flourishing spot the aspect of a desert. The march of destruction was always to be traced for days afterwards by burning villages and destroyed cultivation. Some satisfaction may result from the fact, that there was scarcely an actor in these unhallowed scenes whose end was not fitted to his career. Ambaji was compelled to disgorge the spoils of Mewar, and his personal sufferings made some atonement for the ills he had inflicted upon her. This satrap, who had almost established his independence in the fortress and territory of Gwalior, suffered every indignity from Sindhia, whose authority he had almost thrown off. He was confined in a mean tent, manacled, suffered the torture of small lighted torches applied to his fingers, and even attempted suicide to avoid the surrender of his riches; but the instrument (an English penknife) was inefficient: the surgeon’to the British embassy sewed up the wounds, and his coffers were eased of fifty-five lakhs of rupees 1 Mewar was, however, once Imore delivered over to him; he died shortly after. If report be correct, the residue of his treasures was possessed by his ancient ally, Zalim Singh. In this case, the old politician derived the chief advantage of the intrigues of S. 1848, without the crimes attendant on the acquisition.

Sindhia’s father-in-law, when expelled that chief’s camp, according to the treaty, enjoyed the ephemeral dignity of minister

to the Rana, when he abstracted the most valuable records, especially those of the revenue. [470]

Kumbhalmer was obtained by the minister Satidas from Jaswant Rao Bhao for seventy thousand rupees, for which assignments were given on this district, of which he retained possession. Amir Khan in A.D. 1809 led his myrmidons to the capital, threatening the demolition of the temple of Eklinga if refused a contribution of eleven lakhs of rupees. Nine were agreed to, but which by no effort could be raised, upon which the Rana’s envoys were treated with indignity, and Kishandas1462 wounded. The passes were forced, Amir Khan entering by Debari, and his coadjutor and son-in-law, the notorious Jamshid, by the Chirwa, which made but a feeble resistance. The ruffian Pathans were billeted on the city, subjecting the Rana to personal humiliation, and Jamshid1463 left with his licentious Rohillas in the capital. The traces of their barbarity are to be seen in its ruins. No woman could safely venture abroad, and a decent garment or turban was sufficient to attract their cupidity.

In S. 1867 (A.D. 1811) Bapu Sindhia arrived with the title of Subahdar, and encamped in the valley, and from this to 1814 these vampires, representing Sindhia and Amir Khan, possessed themselves of the entire fiscal domain, with many of the fiefs, occasionally disputing for the spoils; to prevent which they came to a conference at the Dhaula Magra (the white hill), attended by a deputation1464 from the Rana, when the line of demarcation was drawn between the spoilers. A schedule was formed of the towns and villages yet inhabited, the amount to be levied from each specified, and three and a half lakhs adjudged to Jamshid, with the same sum to Sindhia; but this treaty was not better kept than the former ones. Mewar was rapidly approaching dissolution, and every

sign of civilization fast disappearing; fields laid waste, cities in ruins, inhabitants exiled, chieftains demoralized, the prince and his family destitute of common comforts. Yet had Sindhia the audacity to demand compensation for the loss of his tribute stipulated to Bapu Sindhia1465, [471] who rendered Mewar a desert, carrying her chiefs, her merchants, her farmers, into captivity and fetters in the dungeons of Ajmer, where many died for want of ransom, and others languished till the treaty with the British, in A.D. 1817, set them free.

1395. Brother of Ajit, the negotiator of the treaty with the British.

1396. Chief of the Jagawat clan, also a branch of the Chondawats; he was killed in a battle with the Afahrattas.

1397. It is yet held by the successor of Sangram, whose faithful services merited the grant he obtained from his prince, and it was in consequence left unmolested in the arrangement of 1817, from the knowledge of his merits.

1398. The father of Rawat Jawan Singh, whom I found at Udaipur as military minister, acting for his grand-uncle Ajit the organ of the Chondawats, whose head, Padam Singh, was just emerging from his minority. It was absolutely necessary to get to the very root of all these feuds, when as envoy and mediator I had to settle the disputes of half a century, and make each useful to detect their joint usurpations of the crown domain.

1399. She was the grandmother of Man Singh, a fine specimen of a Saktawat cavalier.

1400. [Lalsot, about 40 miles south of Jaipur city. For an account of the battle see Compton, European Military Adventurers, 346 f.]

1401. Megh Singh was the chief of Begun, and founder of that subdivision of the Chondawats called after him Meghawat, and his complexion being very dark (kala), he was called ‘Kala Megh,’ the ‘black cloud.’ His descendants were very numerous and very refractory.

1402. A.D. 1788.

1403. He did not recover his liberty for two years, nor till he had surrendered four of the best towns in his fief.

1404. Father of the present Hamir Singh, the only chief with whom I was compelled to use severity; but he was incorrigible. He was celebrated for his raids in the troubles, and from his red whiskers bore with us the name of the ‘Red Riever’ of Badesar – more of him by and by.

1405. Sheodas and Satidas, with their cousin Jaichand. They revenged their brother’s death by that of his murderer, and were both in turn slain. Such were these times! The author more than once, when resuming the Chondawat lands, and amongst them Badesar, the fief of the son of Sardar, was told to recollect the fate of Somji; the advice, however, excited only a smile; he was deemed snore of a Saktawat than a Chondawat, and there was some truth in it, for he found the good actions of the former far outweigh the other, who made a boast and monopoly of their patriotism. It was a curious period in his life; the stimulus to action was too high, too constant, to think of self; and having no personal views, being influenced solely by one feeling, the prosperity of all, he despised the very idea of danger, though it was said to exist in various shapes, even in the hospitable plate put before him! But he deemed none capable of such treachery, though once he was within a few minutes’ march to the other world; but the cause, if the right one, came from his own cuisinier, or rather Boulanger, whom he discharged.

1406. See the Essay on a Feudal System.

1407. 2 S. 1847 (A.D. 1791).

1408. [Count Benoit de Boigne, a Savoyard, born at Chambery, 1751: served under Mahadaji Sindhia, and won for him his battles of Patan and Mcrta in 1790: defeated Holkar at Lakheri in 1793: resigned his command in 1795, and left India in the next year: died June 21, 1830 (Compton, European Military Adventurers, 15 ff.; Buckland, Dict. of Indian Biography, s.v.).]

1409. Acquired from the actors in those scenes: the prince, his ministers, Zalim Singh and the rival chiefs have all contributed.

1410. It was levied as follows:

Salumbar . . . . Lakhs 3

Deogarh . . . . 3

Singingir Gosain, their adviser . . . . 2

Kosital . . . . 1

Amet . . . . 2

Kurabar . . . . 1

Total . . . . Lakhs 12

1411. [Pandhri, Pandharapatti, a tax on shops, artisans, traders, and persons not engaged in agriculture, levied on their persons, implements, places of work, or traffic; the same as the Mahtarafa (Wilson, Glossary, s.v.).]

1412. Raepur Rajnagar from the Sindis; Gurla and Gadarmala from the Purawats; Hamirgarh from Sardar Singh, and Kurj Kawaria from Salumbar.

1413. In Bhadon, the third month of the rainy season. An account of this festival will hereafter be. given.

1414. The first of these is now the manager of Prince Jawan Singh’s estates, a man of no talent; and the latter, his brother, was one of the ministers on my arrival at Udaipur. He was of invincible good humour, yet full of the spirit of intrigue, and one of the bars to returning prosperity. The cholera carried off this Falstaff of the court, not much to my sorrow.

1415. S. 1853, A.D. 1797.

1416. 2 This person was nominated the chief civil minister on the author’s arrival at Udaipur, an office to which he was every way unequal. The affairs of Mewar had never prospered since the faithful Pancholis were deprived of power. Several productions of the descendants of Biharidas have fallen into my hands; their quaint mode of conveying advice may authorize their insertion here.

The Pancholis, who had performed so many services to the country, had been for some time deprived of the office of prime minister, which was disposed of as it suited the views of the factious nobles who held power for the time being; and who bestowed it on the Mchtas, Depras, or Dhabhais. Amongst the papers of the Pancholis, several addressed to the Rana and to Agarji Mehta, the minister of the day, are valuable for the patriotic sentiments they contain, as well as for the general light they throw upon the period. In S. 1853 (A.D. 1797) Amrit Rao devised a plan to remedy the evils that oppressed the country. He inculcated the necessity of dispensing with the interference of the Saktawats and Chondawats in the affairs of government, and strengthening the hands of the civil administration by admitting the foreign chieftains to the power he proposed to deprive the former of. He proceeds in the following quaint style:

“Disease fastened on the country from the following causes, envy and party spirit. With the Turks disease was introduced; but then the prince, his ministers, and chiefs, were of one mind, and medicine was ministered and a cure effected. During Rana Jai Singh’s time the disorder returned, which his son Amra put down. He recovered the affairs of government from confusion, gave to every one his proper rank and dignity, and rendered all prosperous. But Maharana Sangram Singh put from under his wing the Chandarawat of Rampura, and thus a pinion of Mewar was broken. The calamity of Biharidas, whose son committed suicide, increased the difficulties. The arrival of the Deccanis under Bajirao, the Jaipur affair* and the defeat at Rajmahall, with the heavy expenditure thereby occasioned, augmented the disorder. Add to this in Jagat Singh’s time the enmity of the Dhabhais towards the Pancholis, which lowered their dignities at home and abroad, and since which time every man has thought himself equal to the task of government. Jagat Singh was also afflicted by the rebellious conduct of his son Partap, when Shyama Solanki and several other chiefs were treacherously cut off. Since which time the minds of the nobles have never been loyal, but black and not to be trusted. Again, on the accession of Partap, Maharaja Nathji allowed his thoughts to aspire, from which all his kin suffered. Hence animosities, doubts, and deceits, arose on all sides. Add to this the haughty proceeding of Amra Chand now in office; and besides the strife of the Pancholis with each other, their enmity to the Depras. Hence parties were formed which completely destroyed the credit of all. Yet, notwithstanding, they abated none of their strife, which was the acme to the disease. The feud between Kunian Singh and the Saktawats for the possession of Hintha, aggravated the distresses. The treacherous murder of Maharaja Nathji, and the consequent disgust and retreat of Jaswant Singh of Deogarh; the setting up the impostor Ratna Singh and Jhala Raghndeo’s struggle for office, with Amra Chand’s entertaining the mercenaries of Sind, brought it to a crisis. The negligence arising out of luxury, and the intrigues of the Dhabhais of Rana Arsi, made it spread so as to defeat all attempt at cure. In S. 1829, on the treacherous murder of the Rana by the Bundi prince, and the accession of the minor Hamir, every one set up his own authority, so that there was not even the semblance of government. And now you (to the Rana), listening to the advice of Bhim Singh (Salumbar), and his brother, Arjun, have taken foreigners** into pay, and thus riveted all the former errors. You and Sri Baiji Raj (the royal mother), putting confidence in foreigners and Deccanis, have rendered the disease contagious; besides, your mind is gone. What can be done? Medicine may yet be had. Let us unite and struggle to restore the duties of the minister and we may conquer, or at least check its progress. If now neglected, it will hereafter be beyond human power. The Deccanis are the great sore. Let us settle their accounts, and at all events get rid of them, or we lose the land for ever. At this time there are treaties and engagements in every corner. I have touched on every subject. Forgive whatever is improper. Let us look the future in the face, and let chiefs, ministers, and all unite. With the welfare of the country all will be well. But this is a disease which, if not now conquered, will conquer us.”

A second paper as follows:

“The disease of the country is to be considered arid treated as a remittent.

“Amra Singh cured it and laid a complete system of government and justice.

“In Sangram’s time it once more gained ground.

“In Jagat Singh’s time the seed was thrown into the ground thus obtained. “In Partap’s time it sprung up.

“In Raj Singh’s time it bore fruit.

“In Rana Arsi’s time it was ripe.

“In Hatuir’s time it was distributed, and all have had a share.

“And you, Bhim Singh (the present Rana), have eaten plentifully thereof. Its virtues and flavour you are acquainted with, and so likewise is the country; and if you take no medicine you will assuredly suffer much pain, and both at home and abroad you will be lightly thought of. Be not therefore negligent, or faith and land will depart from you.”

A third paper to Agarji Mehta (then minister):

If the milk is curdled it does not signify. Where there is sense butter may yet be extracted; and if the butter-milk (chhachh) is thrown away it matters not. But if the milk be curdled and black it will require wisdom to restore its purity. This wisdom is now wanted. The foreigners are the black in the curdled milk of Mewar. At all hazards remove them. Trust to them and the land is lost.

“In moonlight what occasion for a blue light? (Chandra- jot).*** “Who looks to the false coin of the juggler?

“Do not credit him who tells you he will make a pigeon out of a feather. “Abroad it is said there is no wisdom left in Mewar, which is a disgrace to her reputation.”

* The struggle to place the Rana’s nephew, Madho Singh, on the throne of Jaipur.

** The Pancholi must allude to the Mahratta subsidiary force under Ambaji.

*** Literally, a ‘moonlight.’ The particular kind of firework which we call a ‘blue light.’

1417. [Mahadaji Sindhia, commonly and erroneously called Madhava Rao, died near Poona, January 12, 1794. See his life by H. G. Keene, ‘Rulers of India’ series; Grant Duff, Hist. of Mahrattas, 343 ff.; W. Franklin, Hist. of Shah-Aulum., 119 ff.]

1418. There are three classes of Mahratta Brahmans Shenvi, Prabhu, and Mahratta. Of the first was Lakwa, Balabha, Tantia, Jiwa Dada, Sivaji Nana, Lalaji Pandit, and Jaswant Rao Bhao, men who held the mortgaged lands of Mewar. [There are four groups of Maratha Brahmans: Konkanasthas, Deshasthas, Karhadas, and Kanvas. The Prabhus are not Brahmans, but the writer caste, like the Kayasths of Hindustan (J. Wilson, Indian Caste, 1877, ii. 17 ff.). The word Shenvi is a corruption of chhiyanave, ‘ninety-six,’ from the supposed number of their sections.]