Chapter 14

Luzon

ON QUIET seas and under drifting clouds of the sort that had afforded Allied convoys so little protection from enemy aircraft on the way up from Leyte, the assault troops for the Luzon invasion headed toward the Lingayen beaches at 0930 on 9 January 1945. Preceded by a heavy naval bombardment, both Army corps established their lodgments without difficulty. Kamikaze attacks against the screening force damaged four ships, but CVE aircraft shot down a total of seventeen enemy planes. By the close of the day, the escort carrier planes also claimed to have destroyed seven light ranks and eighteen trucks in their zone of operations (an area bounded by Hermana Mayor Island, Camiling, Bagabag, and Santa Cruz) . Planes of the 345th and 417th Groups, circling over Camiling village in case they were needed, were dismissed forty-five minutes after H-hour and departed on communication strikes. One squadron of A-20's, however, was called in later during the day to bomb and strafe Villasis and Rosales villages.1

Sporadic Japanese air attacks against the American forces at Lingayen Gulf continued until 18 January, but after the 12th most of them apparently came from Formosa. If reinforcement aircraft reached Luzon, they were few in number and counted for little. Although Fifth Air Force crews experienced slight interference from enemy air while supporting the Luzon campaign and had no difficulty in overcoming such resistance as they met, none could equal the record established by Capt. William A. Shomo, commander of the 82d Reconnaissance Squadron, and Lt. Paul M. Lipscomb of the same organization. Flying an armed photo mission to Aparri on 11 January, they met twelve enemy fighters led by a Betty bomber headed southward down the Cagayan Valley. The Japanese evidently identified the F-6's as friendly Tonys, for Shomo with little difficulty promptly

--413--

shot down the lead bomber and six fighters while Lipscomb dispatched three fighters. Shomo's destruction of seven combat planes in fifteen minutes surpassed any previous achievement in SWPA.2

Landing Area Lingayen Gulf Luzon

Within few days virtually no enemy air organization was left on Luzon. Vice Adm. Shigeru Fukudome, commander of the Second Air Fleet fled to Singapore by flying boat on the 15th and his fleet was

soon disbanded. Vice Adm. Takajiro Onishi took about thirty fighters of his First Air Fleet to Aparri and soon retreated to Formosa. Lt. Gen. Kyoji Tominga organized remnants of his ill-fated Fourth Air Army as the Kenbu composite division on about 8 January and took to the hills for infantry duty; Count Terauchi had already taken his Southern Army Headquarters to Saigon on about 10 December. Thus, Yamashita had to fight a campaign on Luzon without friendly air power.3

Meanwhile, other Allied forces had combined to eliminate the possible risk of serious interference from outside Luzon. The Fourteenth Air Force had been limited in the reconnaissance it could provide by the loss of its base at Liuchow,* but XX Bomber Command, which was maintaining surveillance of Kyushu, sent B-29's on reconnaissance as far south as Singapore after reports of hostile fleet movements around Camranh Bay. Arnold did not consider airfields to be lucrative targets for the B-29's, but in the heat of the moment MacArthur insisted that assistance against Formosa and Okinawa airfields between S-day and S plus 8 was essential if he was to weather the critical period at Lingayen. Accordingly, XX Bomber Command sent fifty-five B-29's against Kagi airfield and Heito arsenal on 14 January and seventy-seven B-29's against Shinchiku airfield on the 17th.4

Having fueled on the 8th, Halsey had struck Formosa on S-day and, aided by overcast skies, slipped the Third Fleet through the hazardous Luzon Strait that night. After a run southward and another fueling, he attacked the coast of French Indo-China on the 12th, but failed to locate any sign of the enemy fleet, which some of the American naval leaders, recalling Leyte, had feared might attempt an attack at this critical juncture. Returning northward, Halsey swept Formosa on the 15th, Hainan, Hang Kong, and Canton on the 16th. After losing three days fueling amidst high seas, he ran out again through Luzon Strait on the night of 20/21 January. He repeated strikes against Formosa on the 21st, taking the only damages of the entire operation when the carrier Ticonderoga was extensively damaged by enemy dive bombers.5 Next day, the Third Fleet moved northward to photograph the Ryukyus, while the Fifth Air Force began a series of strikes against Formosa which would continue until the Japanese surrender.†

* See above, p. 259.

† See below, pp. 471-89.

--415--

Back on Luzon, Fifth Air Force planes were simultaneously isolating the more immediate battleground. On 9 January alone they knocked out fifteen key bridges on Luzon, and from their Mindoro and Leyte bases they continued to press attacks on enemy communications. By the 16th the Fifth Air Force, totaling up minimum claims, reported that it had destroyed 43 locomotives, 291 railway cars, 369 motor trucks, and 42 staff cars in the central plains; 3 locomotives, 42 railway cars, 31 trucks, and 12 staff cars in the Batangas area; and 33 locomotives, 133 railway cars, 68 trucks, and 12 staff cars in the Bicol provinces. This was equal to half of Luzon's prewar locomotives and a quarter of her prewar rolling stock. In addition to this, eighteen tanks, five armored cars, and ten field pieces on the move had been strafed and bombed, despite elaborate Japanese camouflage. The Balete Pass road, cratered on the 4th and 21st, was blocked with 2,000-pound bomb landslides on the 22d.6 In fact, Fifth Air Force pilots, delighted with the Novelty of "rhubarbs," were doing almost too good a job: on the 19th, for example, in an effort to preserve some Japanese facilities for American use, Krueger asked that bridges be bombed only on request and that bombing and strafing of railway equipment be limited to trains in motion.7

By the end of the first week after the landing Sixth Army had established a firm beachhead. With I Corps encounrering stubborn resistance in the foothills bordering the left flank, XIV Corps, despite logistical problems, forged down the plains, reached and bridged the Agno River by 16 January, and thus carved out a beachhead almost thirty miles deep and thirty miles wide.8 Air support had been provided by escort carrier planes of Task Group 77.4, which flew forty-one joint air-ground missions during the week. Because of the rapid advance of the ground troops, the carrier operational zone was twice extended. In addition, strikes were flown on request by 310th Wing aircraft from Mindoro, an operation which placed both Army and Navy planes within the same vicinity. With the air command thus divided, the risk was great, but only one mishap occurred: Navy planes attacked eight P-47's on the 10th near Munoz, southwest of San Jose and outside the carrier aircraft zone. In spite of friendly gestures and refusal of the P-47's to take offensive positions, the CVE pilots shot down one Army plane and holed two others, explaining later that they took the P-47's for Tojos.9

Fortunately, the engineers kept to schedule in the construction of

--416--

an airstrip in the beachhead. The heavy seas which followed hard upon the original landing threatened to frustrate ASCOM's effort to meet the completion date of S plus 8; to get the landing mat and other heavy equipment ashore, it had been necessary to shift all unloading

Luzon Philippine Islands

to the more sheltered San Fabian beaches. Although the engineers were consequently unable to begin work on the old Japanese strip near the Lingayen beaches until S plus 3, most of three battalions concentrated on the effort, and ASCOM had the strip ready on S plus 7--three days before the battleships were due for return to Nimitz. To

--417--

accomplish this, the engineers used simplified construction: shell craters were filled with beach sand and the surface bladed smooth; palm fronds and bamboo mats were placed over the exposed sand to check erosion; 5,000 feet of steel mat were laid and the entire surface sprayed with tar. No drainage was possible, and it was known that the airstrip would deteriorate rapidly once the summer rains came.10

Troop carrier C-47's began to ferry cargo into the Lingayen strip on 16 January, and that same day several P-61's of the 547th Night Fighter Squadron moved in from Mindoro. Next afternoon, P-38's of the 18th Fighter Group and P-40's and P-51's of the 82d Reconnaissance Squadron arrived to bring the FEAF garrison up to requirements for cover and direct support, and at 1830 hours on 17 January the 308th Bombardment Wing formally relieved the escort carriers. The 110th Reconnaissance Squadron reached Lingayen on the 22d, followed next day by the first F-51's of the 26th Photo Squadron.11

Work on a medium bomber field had started near Dagupan on 13 January, but after two aviation engineer battalions had worked six days, a more favorable site near Mangaldan was substituted. With the assistance of an extra aviation engineer battalion, they had the field sufficiently developed by 22 January to receive the 35th Fighter and 3d Air Commando Groups. This strip had a surface of compacted earth, treated with oil as a dust palliative; rains prevented movement of MAG 24, MAG 32, and the 38th Bombardment Group (M) there until 2-3 February. At Whitehead's request, SWPA authorized extension of one of the runways to accommodate PB4Y search planes, but as the engineers had predicted, it would not support operations by heavy planes. Medium bombers so crowded the field, moreover, that the 312th Bombardment Group (L) was substituted for the 345th Bombardment Group (M) on 12 February.12

The Capture of Manila

Because it lacked details of the enemy situation, the Sixth Army had been unable to project in advance a comprehensive strategy for the whole Luzon campaign, but in the week following S-day it became clear that Yamashita was waiting for the Sixth Army to overextend before counterattacking on its left flank. Dispositions of hostile armor at Cabanatuan seemed also to indicate a second counterattack farther southward in the plains, although postwar historical accounts prepared by the Japanese indicate that this was not a part of Yamashita's

--418--

plan. Alerted by Allied minesweepers in the gulf, on 6 January he ordered his 23d Division and the 58th Brigade into the foothills on the north side of the intended Allied beachhead with instructions to prepare for an attack from that direction. On 15 January, four days after the landing, he drew in the 2d Tank Division to Tayug, where it would be in position to cooperate with the 10th Division in an assault on the Americans as they moved against San Jose.13

MacArthur's decision on 17 January to move XIV Corps southward toward Clark as rapidly as possible, with I Corps in echelon to the left rear, involved a calculated risk-the kind of gamble that Krueger had rejected during the early days at Leyte when invited to drive southward from Carigara Bay toward Ormoc. The reserve forces (the 32d Infantry Division, 1st Cavalry Division, and 112th Cavalry RCT) that might be required to repel an attack on Krueger's flank could not be expected at Lingayen until 27 January.14 But there was now one important difference: at Leyte there had been no effective air support; at Lingayen on 17 January the 308th Wing took over from the CVEs with sufficient strength to offset the risk assumed. The wing's strength increased as the ground troops advanced until by early February it commanded a still growing force of 380 planes--fighters, dive bombers, light bombers, and medium bombers. Moreover, the 310th Wing at Mindoro possessed an equivalent garrison which could be called upon as required in Lingayen. Support aircraft parties (SAP) accompanied each separate regiment, division, and corps, as well as army headquarters, to facilitate the cooperation desired. Already Fifth Air Force planes from Mindoro and Leyte had effectively checked enemy movement along the roads during daylight hours, and, as a Japanese tank commander later explained, cross-country movement in an area covered with rice paddies was impossible even with ample gasoline, which the Japanese did not possess.15

Krueger had issued the necessary orders on 18 January, and XIV Corps pushed southward against only ragged opposition. The 40th Division captured Tarlac on the 21st while the 37th Division pivoted slightly to the east to capture Victoria for left flank protection. On the 21st Krueger ordered an advance into the Clark Field area. The first real opposition was encountered on the 23d, when elements of the 40th Division discovered strong enemy positions in the hills to the west and southwest of Bamban, obviously designed to deny use of Highway No. 3--the easy route to Clark. After securing Bamban

--419--

on the 25th, the division turned against the enemy entrenchments. In bitter fighting against Japanese cave positions, bristling with machine guns taken from wrecked planes at Clark and with AA units drawn from the same area, it secured the high ground west of Bamban on the 26th. Meantime, the 37th Division had driven toward the eastern side of Clark Field, reaching a point just north of Angeles without serious opposition on the evening of the 26th. Now in the advance, that division secured Angeles, and although slowed by mine fields, it captured Clark and entered Fort Stotsenburg on 28 January. Elements of the division then moved south along the highway to San Fernando (Pampanga Province) and dispatched patrols southeast to Calumpit.16

Although in its progress XIV Corps found little need for close air support, demands for reconnaissance and photography were exceptionally heavy until the enemy situation cleared. At Krueger's request and with his assurance that all civilians had been evacuated, the Fifth Air Force sent 494th Group Liberators against Bamban town on 18 January. Next day, Whitehead committed both the 22d and 494th Groups to Bamban and adjacent hill fortifications, but weather forced cancellation of these strikes and of scheduled light and medium bomber attacks against Tarlac. Bamban stores and fortifications were attacked by the 22d Group on the 20th. On the 21st, shortly after the heavies were airborne, Fifth Air Force was notified that Bamban lay within a newly established bomb line; fortunately, the bombing caused no damage to American troops. Thenceforth, the Fifth Air Force requested a 24-hour advance notice of all such changes. The 345th Group's Mitchells attempted a strike against Tarlac on the 20th but weather once more frustrated it; clearing weather on the 23d, however, permitted thirty-six A-20's of the 31th Group and eighteen B-25's of the 345th to bomb and strafe all enemy activity around San Jose, San Nicolas, and Floridablanca towns in one prolonged sweep. Because he desired to protect the Filipinos, MacArthur had ordered on the 9th that bombing and strafing be limited to trucks on the. main roads (but not side streets) through towns, villages, and barrios; on the 20th, upon representation from the Sixth Army, he allowed bombing of towns without approval from GHQ, but only in direct support of ground operations.17

Well-prepared Japanese defenses on the I Corps front quickly persuaded division commanders to forward air requests, and nearly all

--420--

of the fifty-six close support missions flown between 17 and 28 January were directed to this sector. Air action on 22 January against an augmented enemy battalion, dug in with tanks, mortars, machine guns, and artillery in the Cabaruan Hills, proved especially noteworthy. Although surrounded by the 1st and 20th Infantry Regiments, this battalion was causing numerous casualties; shortly after noon a forward observer of the 11th SAP directed twenty-three A-20's of the 672d Squadron on two bombing and four strafing runs across the position. A Japanese prisoner later declared that 25 per cent of his company, including the company commander, had been killed; he estimated casualties to be comparable or higher in other companies and reported complete demoralization among survivors. After asecond strike by nine SBD's on 25 January, the ground troops cleared out the remnants within two days.18 Maj. Gen. Edwin D. Patrick informed the support party that he had not believed it possible for air and infantry to work so closely together.19 Other air strikes attacked enemy fortifications on the high ground north of the Rosario-Damortis road, where hardly a single ground unit attacked without preliminary air bombardment. Eight 110th Squadron P-40's (as an added precaution against Japanese transients at nearby Cabanatuan) covered the homeward route of 6th Ranger Battalion scouts who, after a daring infiltration from Guimba to Pangatian, on 30 January had rescued 512 Allied prisoners of war from a concentration camp.20

Sixth Army reinforcements had reached Lingayen on 27 January as scheduled. The 1st Cavalry Division, reinforced by the 112th RCT, was promptly routed to Guimba, while the 32d Division passed to control of I Corps. With rhe 1st Cavalry completing its concentration early in February at Guimba, whence it could attack southward to Cabanatuan and then by Highway 5 toward Manila, and with the 43d Division poised to cross the Pampanga at Calumpit, the Sixth Army was ready to begin the drive to capture the capital of the Philippines.21 Seeking a quick victory, MacArthur had directed preparations for a number of supporting invasions. Two of these operations--coded MIKE VI and MIKE VII and employed in the reverse order--would now be executed.

Since the original plans for Luzon contemplated little more than the tactical employment of air power, Kenney and Whitehead had spoken for an exploitation operation which would give them heavy bombardment bases as far northward as possible, MacArthur gave his

--421--

verbal approval and SWPA had cut orders on 21 December for execution of an operation (MIKE III) designed to seize the area around Vigan on 26 January, a target date soon postponed by three days.22 The development of a heavy bomber base at Vigan, however, threatened diversion of engineers from projects viewed by Krueger as more urgent, and after the landings at Lingayen the enemy situation convinced MacArthur that MIKE III was not immediately practicable. On the morning of 12 January he suddenly ordered his planners to prepare a study for use of the same forces in a landing near San Antonio on the Zambales coast of west-central Luzon (MIKE VII). The expedition was to seize San Marcelino airfield and the town of Olongapo, clear Subic Bay, and march eastward to cover the entrance to Bataan. Two days later, operations instructions set the target date for 29 January (B-day), ordered the Eighth Army to stage and initiate the operation, and committed XI Corps with its 24th Infantry Division and one RCT. AAFSWPA was to provide support, assist the CVE convoy cover, and install the 348th Fighter Group, one flight of the 421st Night Fighter Squadron, and one flight of the 3d Emergency Rescue Squadron (all under the 309th Bombardment Wing) as quickly as possible. Engineers from XI Corps were to prepare a fair-weather fighter strip at San Marcelino by B plus 5 and complete the air facilities by B plus 15.23 Convoy and local cover, as well aslocal air support, could easily be flown from Mindoro. Indeed, FEAF had seriously questioned whether an air garrison would he needed but decided that it would be worth while to base a few units at San Marcelino, whence they could move inland to Clark Field as soon as it was repaired.24

Planning staffs had long been considering a number of possible amphibious and airborne invasions south of Manila, but earlier studies were superseded on 5 December by MIKE VI. According to this plan, the Eighth Army, employing a reinforced 11th Airborne Division, was to seize two beachheads in the Nasugbu-Pagbilao coastal sector of Tayabas Province on 30 January (X-day), conduct overland and overwater movements to contain the enemy, and, if all went well, move against Manila. The 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment was to be concentrated at San Jose in Mindoro for air movement as the task force reserve. AAFSWPA was directed to destroy hostile air and surface forces at the beachhead, deny hostile movement in Cavite, Batangas, and Tayabas provinces, provide convoy cover and direct

--422--

air support, and prepare to drop the 5 I rth Regiment. Because of the closeness of the target area to Mindoro, no airfields were to be built; other than two air warning detachments and two SAP's, no air force troops were to accompany the expedition. As in MIKE VII, AAFSWPA delegated the air mission to the Fifth Air Force, and directed the Thirteenth Air Force and RAAF Command to support it as requested.25 To supervise the new operations at closer range the Fifth Air Force moved its headquarters and those of its closely associated commands from the mud of Leyte to the dust of Mindoro, relieving the 310th Bombardment Wing at midnight on 29 January. At the same time, the Fifth Air Force relinquished control at Leyte to the XIII Fighter Command, which had just moved northward from Sansapor to serve as an advanced echelon of the Thirteenth Air Force. Since operation of troop carrier planes from Hill and Elmore fields would circumscribe offensive strikes from those bases, the Fifth Air Force planned to move the 317th Troop Carrier Group's C-47's there on 31 January for as short a stay as possible.26

Along the Bataan-Zambales coast in the MIKE VII target area no considerable troop cancentrations were evident, but Eighth Army and Seventh Fleet were apprehensive about the old American defenses on Grande Island at the mouth of Subic Bay. Interpretation of photographs taken on 10 January revealed heavy activity at Warwick battery, which had been the heaviest U.S. fortification. Between 21 and 28 January Fifth Air Force bombers and fighters accordingly dropped 175 tons of bombs upon the small island in a series of uneventful missions. Medium and light bombers as well as fighters attacked Olongapo town and swept Bataan looking for what proved to be exceedingly sparse military targets. Save for sporadic ground fire there was no opposition. Several flights, finding no targets, bombed Corregidor as a last resort, and some even returned their bombs to base.27

According to plan, Fifth Air Force fighters covered the B-day convoy, but neither they nor the planes from six CVE's encountered any hostile aircraft. Lacking air and naval targets, the CVE planes finally conducted "hunter-killer" antisubmarine operations off Manila Bay, where an underwater craft damaged an Allied transport on the 30th. The A-20's of the 3d Bombardment Group had been alerted at San Jose, but when no call came through for their services they attacked

--423--

other Luzon objectives. Without opposition, Struble's task force began landing XI Corps at 0830 hours, 29 January, without the formality of a bombardment. Once ashore, the assault troops found San Marcelino strip in the hands of friendly guerrillas, and the few Japanese at Olongapo withdrew without an effort to destroy the old American naval shops. Subic town and Olongapo were captured by the close of B-day, and reconnaissance troops were moving rapidly south from Castillejos pass, four miles north of Subic Bay, without any difficulty. Grande Island was taken on 30 January, and Navy minesweepers immediately began clearing Subic Bay for port use. Leaving a small force in the rear, XI Corps drove along Highway No. 7 to meet elements of XIV Corps moving west on the same road. By 31 January the two forces were only about 10,000 yards apart after having encountered heavy enemy opposition in Zig-Zag pass, just west of Dinalupihan.28

At dusk on 30 January the Fifth Air Force had assumed full responsibility for close support and cover at San Antonio, thus relieving the last of Nimitz' escort carriers from their long tour of duty in the SWPA. The old American airfield at San Marcelirio proved "a natural for dry weather strips"; with a clay and gravel topping the strip was opened on 4 February. Transports carrying air echelons of the tactical garrison arrived that day, and within the next several days all of the air units specified for San Marcelino had reached their new station. Construction having proved so easy, MacArthur ordered the task force to build additional dry-weather hardstands to accommodate the 345th Bombardment Group, and after a hurried but efficiently accomplished movement from Lingayen, this group's B-25's began operations from San Marcelino on 15 February.29 With the establishment of air units in western Luzon, the 309th Bombardment Wing, commanded by Col. Norman D. Sillin since 16 December 1944, was ready not only to support ground fighting on Luzon but to reach far out into the South China Sea against enemy shipping.

In view of Japanese concentrations in Manila and in southwest Luzon, MIKE VI involved a serious risk for the 11th Airborne Division. Its pack artillery would be inadequate, but the Eighth Army was unwilling to provide much additional firepower for an operation which it considered "nothing more or less than a reconnaissance in force." At Kinkaid's suggestion, X-day was postponed to 31 January so that a cruiser force from San Antonio could be on hand to offer fire support

--424--

Bombing Corregidor

Return to Clark Field

with its naval rifles, but these vessels would be vulnerable to the hayabusa boats believed lurking in Balayan Ray. Vigorous air reconnaissance, strong air activity to isolate the beachhead and destroy suicide boats, a successful reinforcing paratroop drop, virtually continuous air strikes to augment the divisional artillery, and not a little trickery would be necessary if MIKE VI were to succeed.30

Following GHQ orders of 16 January, Fifth Air Force fighter and photo sweeps maintained surveillance of roads southward from Manila to detect troop movements, and of the mouths of the Balayan, Batangas, and Tayabas bays to locate suicide boats. Results were reported daily to GHQ and the Eighth Army. Actually, however, little movement was observed. At the request of the Eighth Army, A-20's and B-25's, cooperating with Allied PT boats to neutralize the hayabusa threat, searched and bombed villages along the coasts of the bays, concentrating particularly on Santiago, where guerrillas reported suicide boats hidden under houses along the waterfront. Fighters dropped napalm, its first use against Luzon, upon a reported hideout at Cape Santiago on 22 January. Beginning a series of eleven raids against Cavite on 24 January, the 5th and 307th Groups of XIII Bomber Command pulverized this former American naval yard lest its rehabilitated fortifications and garrison forces flank the route of advance toward Manila. After its strike on 3 February, the Thirteenth Air Force pronounced targets on Cavite Island and Cafiacao Peninsula to be 96 per cent destroyed. Allied naval planners, who hoped to repossess the base, were reported to wince with each successful strike report.31

To confuse the Japanese defenses in southwest Luzon, a Seventh Fleet task group of LCI's, PT's, and beach-jumpers simulated an attempt to land around Unisan in eastern Tayabas Bay on the night of 22/23 January, while troop carriers dropped dummy paratroopers in a zone east of Lake Taal in Batangas Province. Enemy radars, which the air forces had left unmolested, were reported frantically active. Another such diversion, without paradummy drop, was executed in the same area on the night of 30/31 January. Admiral Fechteler's task force moved in close to the beaches at Nasugbu during the early morning hours of 31 January under cover of the latter diversion. Hampered only by poor landing beaches, the 188th RCT went ashore to feel out the opposition, and when nothing serious materialized, Maj. Gen. Joseph M. Swing sent in the remainder of his airborne

--425--

division. An umbrella of four to eight P-47's and P-38's, each loaded with bombs in case the ground controller called on them, covered the beachhead while 3d Group A-20's circled in the vicinity. During the day P-47's dropped sixteen bombs on buildings at Aga near Manila, and other planes bombed the Batangas strip lest some of the derelicts were still serviceable.32 As the Japanese later told the story, the landing at Nasugbu had found them unprepared in an area out of reach of their better Batangas defenses. All that they could do immediately was to send out a scratch force of about thirty suicide boats on the night of X-day, an attack which destroyed only one American subchaser.33

The operation remained a reconnaissance in force, however, until the 11th Airborne could advance far enough inland so that a drop of the 511th Regiment might secure commanding terrain at Tagaytay; Eichelberger was unwilling to employ the airborne regiment more than one day's march ahead of the division. Fortunately, Swing had all the air support he could use, including a constant column cover of at least four fighter-bombers. Fifth Air Force and Eighth Army operations officers had studied photographs of Route 17, the road leading inland toward Manila, and had carefully plotted enemy defenses along the way. After these defenses had been speedily eradicated by fighter-bombers and A-20's, the division was able to advance rapidly in column with no danger to its flanks. Eichelberger, who accompanied the column, radioed MacArthur that A-20 support was "grand," and that the advance would have been faster had the column not been moving up-hill all the way. Passing the remains of Aga at noon on 2 February, the division was within striking distance of Tagaytay Ridge.34

Back in Mindoro, the Fifth Air Force was ready to drop the 51xth Regiment in three waves, two on the 3d and one on the 4th. Contrary to instructions published by the 54th Troop Carrier Wing and the 11th Airborne Division during mutual training in New Guinea, no radio or other signal was to be used to coordinate jumping. The leader of each flight would jump as the flight reached a "go line," and pilots of following planes would flash their green signal lights as the men on the lead plane jumped. On the morning of 3 February, A-20's of the 3d and 417th Groups attacked the old Japanese fields at Lipa and Kalingatan, while forty-eight C-47 transports of the 317th

--426--

An Air Liaison Officer in an L-7 Marking Target

P-38 Bombing Ahead of Ground Troops

P-38's Droping Napalm Near Ipo Dam

Group took off at Mindoro and joined their P-38 escort. Flying a circuitous route to avoid known AA emplacements, the C-47's reached the drop zone at 0820, and the first eighteen planes of the formation placed their paratroops precisely on the area marked with smoke-pots by advanced ground scouts. One of the lead planes in a following flight, however, accidentally released a parabundle, and immediately the tense paratroopers bailed out of each successive plane, landing about six miles short of the drop area. During the interval between the return of the transports and 1100 hours, when the second wave took off, the paratroopers awaiting movement were expressly briefed to ignore scattered parachutes on the ground short of the proper zone. But again, despite verbal orders and red signal lights, most of the paratroopers jumped short of the drop zone. On the next morning the last jump landed in the proper area. All told, only 38.4 per cent of the 2,055 men had landed where they should have; only slight injuries to 36 paratroopers represented the total cost of the drop, however, and the scattered jump actually facilitated seizure of its objectives. Within three hours after the last jump, the seven-mile Tagaytay Ridge and the critical road junction where the ridge road, Highway 25, joined the route to Manila had been seized. By nightfall of 4 February the 15th Airborne was at Silang, only twenty miles south of Cavite.35

Now that the division was in position to drive toward Manila, the risk came not so much from the threat of Japanese resistance as from a lack of supplies. Unfavorable landing beaches at Nasugbu and an overhasty withdrawal of amphibious vessels had left Swing short of essential resupply. As early as the morning of the 3d he had only 1,500 gallons of motor fuel--less than a day's supply. He had already cleared an airstrip near Nasugbu, and Eichelberger appealed personally to Whitehead for immediate delivery of enough gasoline to tide the division over until naval resupply arrived. The radio reached Mindoro at about noon. All troop carriers there were committed to the final jump of the 511th Regiment, but Whitehead intercepted another squadron hauling between Mindoro and Leyte and sent them to Nasugbu late that afternoon. Rain had so softened the runway that only the first plane succeeded in landing, but next day 10 C-47's successfully delivered 89 drums (4,895 gallons) of gasoline and picked up wounded soldiers. A priority request for ten complete tank tracks

--427--

followed. Before normal resupply began, the troop carriers had made twenty-seven emergency trips to Nasugbu as well as fulfilling a commitment for resupply of the paratroopers through the three days following the final drop.36

As the 15th Airborne Division stood poised for its drive to Manila, Sixth Army was approaching the northern outskirts of the city. With the high ground east of Lingayen secure, I Corps, with the 32d Division in the line, had wheeled its 25th and 6th Divisions eastward to drive the Japanese back into the Caraballo Mountains, thus to end any danger of a flank movement into the central plains. Fighting on this front was sharp, especially at Munoz, where the Japanese opposed with a suicide tank company, infantry, and artillery, all strongly entrenched. After failing to capture the town, the 6th Division bypassed it and moved on against San Jose, while the 25th Division, as the northern arm of a pincer movement, moved on Lupao. The 32d Division drove out toward the entrance of the Villa Verde trail to clear the enemy from the Natividad-San Nicolas-Tayug triangle, enemy tanks reported in the area having been destroyed by Allied air attack or withdrawn. On the XIV Corps front, the 40th Division drove the Kenbu force back into the foothills of the Zambales Mountains.37

With enemy forces contained, Krueger ordered XIV Corps to attack Manila from the north. The 1st Cavalry, covered by a constant Marine fighter force which permitted attack in column, moved out from Guimba, crossed the Pampanga at Cabanatuan, and drove rapidly down Highway 5. Having covered almost roo miles in less than 3 days, the cavalry reached Grace Park in northeastern Manila on the evening of 3 February. During the next two days the division forced a stoutly resisting enemy back to the Pasig River, but it failed to force a crossing. The 37th Division's progress from Calumpit was retarded by many wrecked bridges, but it reached the Pasig in force on the evenirig of the 5th. Completely surprised by the rapidity of this attack, the Shimbu force (Forty-first Army and attached naval troops) was unable to rally an effective defense in the northern outskirts of Manila. Having progressed northward without real difficulty, the I rth Airborne Division on the 5th entered the southern suburbs of Manila near Nichols Field.38 There would be another month of bitter fighting, during which Manila-once called the "Pearl of the Orient"would be reduced to semi-rubble and 16,625 Japanese would be rooted

--428--

out and slain, but MacArthur announced on 5 February that the assault phase of the Luzon campaign had been completed.39

With the 308th and 309th Bombardment Wings approaching full strength and with units at Mindoro and Leyte available for support, the Fifth Air Force had supported the ground campaign to the fullest. Where there was Japanese resistance, there the Fifth's aircraft concentrated in such numbers that only a generalized description of their operations is possible. Japanese fortifications at Umingan which held up the advance of the 25th Division were attacked on 1 February by successive waves of SBD's and P-47's carrying 500-and 1,000-pound bombs, and by a wave of B-25's which strafed and dropped parafrags on Japanese troops driven out of doors by the dive bombers. Eight tons of bombs smothered Japanese resistance on this one day. Enemy fortifications in the Zambales foothills were heavily attacked as were fortifications on the northern flank of I Corps. Using large quantities of napalm, the 309th Bombardment Wing literally burned the Japanese out of Zig-Zag pass in 5 days of fighter-bomber attacks on 7-11 February, while 31 transport missions dropped the ground forces 78.5 tons of supply and equipment. During the attack of the1st Cavalry, forward air controllers mounted in jeeps directed strikes of nine covering SBD's, which rotated every two hours from dawn to dusk against targets likely to hold up the column. Air strikes against pinpointed artillery and mortar positions around Nichols Field (MacArthur would not permit strafing and bombing within city limits) greatly assisted the lightly armed 11th Airborne.40

Meanwhile, attack bombers had continued operations designed to isolate Luzon. On 31 January twelve B-25's of the 822d Squadron flew from Lingayen to intercept a run of three destroyers from north Luzon to Formosa: within fifteen miles of Formosa the B-25's sank the Ume and damaged the other two destroyers. Four 41st Squadron P-47's, escorting the Mitchells, shot down two Zekes and an Oscar.41 Thus the air forces were everywhere active as Sixth Army troops drove on Manila. "Of the many Pacific tactical air operations,'' the JCS observed at Potsdam, "we think the most striking example of the effective use of tactical air power, in cooperation with ground troops and the Navy, to achieve decisive results at a minimum cost in lives and materiel was the work of the Far East Air Forces in the Lingayen-Central Luzon campaign."42

--429--

Consolidation

After the capture of Manila, Yamashita retained the main body of the Fourteenth Area Army (Shobu force) in the northern Luzon mountains, The Kenbu force, driven into the Zambales Mountains, continued to threaten Clark Field and Stotsenburg. Most of the Shimbu force had managed to escape Manila into partly completed mountain defenses around Laguna de Bay, and other elements held islands in Manila Bay or were attempting to escape into mountainous Bataan. Defensive troops in the Bicol provinces were virtually intact. Reduction of these pockets would take time, and MacArthur's immediate purpose was to contain and weaken the enemy while the Sixth Army secured the portion of Luzon needed for an Allied base. On 5 February he ordered Krueger: 1) to clear Bataan and Manila Bay in order to gain prompt use of the port; 2) to clear southern Luzon westward of Laguna de Bay and the Bicol peninsula prior to opening Batangas Bay; 3) to clear the northwestern coasts of Luzon above Lingayen for airfield development; 4) to drive into the mountains and contain or destroy hostile forces north and east of the central plains and Laguna de Bay; and 5) to prepare for future operations in the Cagayan Valley.43

As the American forces undertook to clear the port of Manila, remnants of Japanese units sought safety across the bay on Bataan and at Corregidor. Heavy barge traffic, noted by fighters on 11 February, was vigorously strafed by 348th Group planes during the following four days, with claims of 2,000 enemy soldiers killed. But other small craft managed the short trip at night.44 Ordering the 1st RCT of the 6th Division moved to Dinalupihan, Krueger formed his plan of attack. On D-day (15 February) the 15 1st RCT would move by water to Mariveles, a village at the southern tip of Bataan opposite Corregidor, while the 1st RCT would work down the east coast of Bataan. After a juncture on the east coast to cut all escape routes from Manila, the two teams would eventually bisect Bataan at the Pilar-Bagac road preliminary to mopping-up maneuvers. Corregidor would be taken by the 503d Parachute Regiment which was to be loaded at Mindoro and dropped on D plus 1, and a battalion of the 34th Infantry Division, having moved previously to Mariveles, would cross to Corregidor shortly after the paratroop landing. Admiral Struble would command the supporting naval forces, a cruiser-destroyer

--430--

group (Task Group 77.3) and the amphibious group (Task Group 78.3).45

Air action against Bataan, which began as cover for the seizure of San Marcelino, was intensified as the target date for the Mariveles landing approached. All visible targets in the southern section of Bataan were hit by twenty-four B-29's, seventy-two A-20's, and sixteen fighters on the morning of 10 February; twenty-four B-24's, seventy-three A-20's, and twenty-seven fighters attacked again that afternoon. Mariveles town was destroyed by the heavy bombers. Raids were continued on a similar scale through the 15th, and during the morning of that day, after a short naval bombardment, the 151st RCT secured its objectives against only slight ground opposition. The 1st Infantry Division began its attack on 13 February and moved down the coast to join the 151st five days later just north of Cabcaben. That same day elements of the 149th RCT, following a "rolling air barrage," started across the Pilar-Bagac road. Begun at 0700 and continued until 1700, the barrage employed forty-eight B-25's and sixty fighters in the largest and longest close support mission in the sector. On 20 February elements of the 1st Infantry which had taken over the attack reached Bagac and reported that fires and Japanese bodies found blown to bits and hanging from trees attested the remarkable fury of the barrage. Organized resistance on Bataan was declared broken by the capture of Bagac.46

Japanese defenses and the terrain of Corregidor made the task of 503d Paratroopers--the "Rock Force"--most hazardous. The island had been fortified as the key American defense for Manila harbor, and within its concrete tunnels and underground battlements U.S. Army troops had defied the Japanese for nearly six months in 1942. Plans for dropping paratroops on the small island were particularly daring. The only really suitable drop zone was Kindley Field on the "tail" of the island, an area dominated by Malinta Hill and the high mass of the island called "Topside." The only other area was "Topside" itself, where aerial photographs showed only two small, obstacle-studded drop areas, the former parade ground and a tiny golf course: both were surrounded by splintered trees, tangled undergrowth, and wrecked buildings. The slightest miscalculation would put paratroopers upon nearby cliffs or into the sea. The commander of the 503d Regiment talked of jump casualties of 20 per cent, but he agreed to seize "Topside" in time to cover the amphibious assault at San Jose

--431--

Corregidor

beach, which was between "Topside" and Malinta Hill. No one knew the strength of the Japanese forces holding Corregidor: Sixth Army guessed approximately 850 men, but during December the Japanese had moved marines there, and the garrison, swollen by escaping soldiers, actually approached 6,000 men at the time of Allied attack.47

Once cleared for attack by GHQ on 22 January, Corregidor had received a substantial part of V Bomber Command's heavy bomber effort, and other planes commonly made it a target of last resort. With additional tonnage delivered by Seventh and Thirteenth Air Force heavies, Corregidor, less than one square mile in area, had absorbed 3,128 tons of bombs by 16 February, the heaviest concentration ever employed in the SWPA. Antiaircraft fire, never particularly severe, ceased on 12 February, but two days later carefully concealed guns scored hits on Allied vessels off Mariveles before they could be silenced by counterfire and aerial strikes. During the early morning hours of the 16th, moreover, the Japanese ran up the steel doors on the old ammunition magazines and brought out some thirty hayabusa boats for an attack which damaged four Allied vessels off Mariveles, Despite the 3,128 tons of bombs dropped on Corregidor, the Japanese troops hiding in the bowels of the battered island obviously remained very much alive.48

At 0759 on 16 February twenty-four B-24's winged away from Corregidor after dropping frag bombs on the island's gun positions. Between 0800 and 0829 eleven B-25's bombed AA positions and the south coast of the island, while thirty-one A-20's bombed and strafed both Corregidor and nearby Caballo Island, where a few AA batteries were operating. Precisely at 0830 the lead C-47 of the 317th Troop Carrier Group passed over the drop zone at 300 feet, observing no activity; at that moment the 3d Battalion, 34th Infantry, pushed off at Mariveles in LCM's. Very quickly, before the Japanese could recover, fifty-one C-47's of the first mission, wheeling over the two small drop areas in counter-rotating orbits, deposited their eight man "sticks" from 500 feet. By 0932 all of the transports had made at least three precise runs over their zones. As the paratroopers landed, seventy A-20's strafed and bombed targets on Corregidor and Caballo, and at 0930 naval vessels commenced fire against San Jose beach preparatory to the amphibious landing at 1028. Support aircraft controllers, dropped by parachute or airborne in a hovering B-25, directed

--433--

close support missions throughout the morning, and shortly after noon the C-47's were back with more paratroops and parabundles. This drop, like the one in the morning, was marred only by a strong and tricky surface wind which blew some of the men over the cliffs or into obstacles outside the drop zones. Enemy machine-gun fire caused a few casualties and damaged a few planes, but casualties for the day were only 10.7 per cent, or 222 men out of the 2,065 dropped.49

Once the "Rock Force" was ashore, operations progressed smoothly. Because of the favorable tactical situation, paratroopers scheduled for drops on the 17th were flown to San Marcelino and returned by water to San Jose beach. Japanese plans for defense had ignored airborne attack, and once "Topside" was lost, the enemy's positions and wire communications could not be used effectively. Air support strikes continued on call and were reported to be very effective: napalm penetrated into some caves as deeply as thirty-five feet, and on the 19th demolition bombs reached an underground barracks, killing some 500 Japanese. By 27 February only a few parties of Japanese remained on the island. MacArthur ordered cessation of all air attacks against the island and derelict ships in the bay on the 28th, and on 1 March Manila Bay was being used as an Allied anchorage.50 "Corregidor," observed MacArthur after an inspection, "is a living proof that the day of the fixed fortress is over."51 Elsewhere on the XI Corps front, the 40th Division was battling the Kenbu force in the Zambales Mountains. Fighting from cave positions in the almost perpendicular cliffs of the Snake Hills, the enemy had slowed the division to a snail's pace. At the suggestion of Fifth Air Force, the division pulled back to provide a safety zone of 1,000 yards, and then on 21 and 22 February a total of 163 B-24's placed 575.5 tons of 500-and 1,000-pound bombs on the caves; fighter-bombers saturated the positions with napalm on the same days as well as on the 23d, just before the division renewed its attack. The advance proceeded now against slight opposition, and by 25 February the 40th Division had broken up the last organized resistance of the Kenbu force.52 Guerrilla forces moving up the west coast of Luzon, and the 38th Division, transferred from Bataan to the Zambales, gradually eradicated small parties of the enemy with assistance from the air. Late in the month fifty fighter sorties were flown to Mount Pinatubo. Vegetation and the terrain usually prevented assessment of results

--434--

by the pilots, but constantly encouraging messages from the SAP controller gave cause for satisfaction. On 5 March missions by twelve P-47's of the 460th Squadron against High Peak were particularly successful: when the ground troops moved in there after a napalm and artillery attack, they counted 574 dead Japanese. By the middle of March the Kenbu force, with many men ill and starving, was nearing complete eradication.53

Coincident with the clean-up of Manila, elements of XIV Corps were penetrating to the edge of Laguna de Bay effectively to divide enemy forces to the southeast and southwest of the city. After the 6th Infantry and 1st Cavalry Divisions pushed into the mountains north of Laguna, where the former captured Montalban by the end of February, they both reached defensive lines consisting chiefly of elaborate cave positions which had been prepared for delaying action by men who could expect only death. The positions were fairly well stocked with food, equipment, and weapons of all types from the Manila dumps, and the advance became necessarily slow. The usual method of attack was to smother the caves with air and ground bombardment so that demolition parties could approach and seal the tunnel entrances, usually trapping about twenty-five Japanese to each cave. Heavy bombers struck every significant target, especially enemy concentrations in the villages of Antipolo and Ipo. On 6 March 98 B-24's dropped 250 tons on Antipolo, and 450 fighter attacks in the area between 8 and 11 March further lightened the task of the 1st Cavalry-the division reported that the "terrific bombing" had "literally blown [the enemy] out of his defenses." The 1st Cavalry entered the town on the 12th, where it was relieved by the 43d Division next day.54

Relieved of operations northeast of Manila by XI Corps and now concerned with operations southeast of Manila and east of Laguna, XIV Corps moved the 1st Cavalry toward Infanta on the coast, which it captured on 24 May. After exchanging the 38th for the 6th Division on 30 April, XI Corps gradually overcame the Shimbu force's southern pocket, and by early May it had surrounded an estimated 4,700 entrenched combat troops, well equipped with arms and ammunition, at the juncture of the Ipo and Angat rivers. Another force of about 2,700 men, remnants of infantry and shipping regiments, was cornered in the vicinity of Santa Maria-Bosoboso, and 6,200 more were holding the Mt. Oro-Mt. Pamitinan-Mt. Purro area. The corps

--435--

predicted "bitter" and "desperate" opposition.55 Late in April MacArthur called attention to the low water supply reaching Manila and suggested that the Ipo dam be captured as a priority objective; if this reservoir continued in Japanese hands or was destroyed, Manila faced a summer epidemic of enteric disease. New and more speedy tactics of attack were in order.56 The V Fighter Command accordingly prepared for the largest mass employment of napalm in the Pacific war: on 3-5 May a total of 238 fighters saturated the outlying defenses of the Ipo area with napalm and demolition bombs. These attacks proved very destructive, and, more important, when the fire exploded near Japanese positions, the usually stoic occupants seemingly lost all caution and fled into the open, easy targets for other forms of attack. The 43d Division had jumped off on 6 May, and as the Japanese were pressed back, V Fighter Command repeated the same general pattern of attack on 16-18 May. Operations officers carefully divided the 5-square-mile area held by the Japanese into sectors, and then sent 673 Lightnings, Thunderbolts, and Mustangs to turn the area into a sea of flames. Napalm-laden P-38's and P-47's, flying at 50 to 100 feet, attacked first, followed by P-51's which strafed and bombed the terrified Japanese as they tried to escape the conflagration. On the second day A-20's with frag bombs aided the Mustangs. As the 43d Division moved ahead with negligible resistance, it estimated conservatively that at least 650 Japanese had been killed by air action alone, while many others had been slaughtered as they ran from their caves into mortar, machine gun, and bomb bursts. At least 75 to 100 caves had been sealed, many known to have contained the enemy, and over 2,100 dead soldiers were counted in the area. The Ipo dam, although prepared for demolition by the enemy, was captured without damage.57 After similar attacks had been made against the Santa Maria-Bosoboso pocket in advance of the 38th Division, stiff resistance immediately collapsed. Here, some 700 enemy bodies revealed the effectiveness of the air and artillery bombardment. Aided by smaller air support missions against more scattered enemy bands in the Mt. Oro-Mt. Pamitinan-Mt. Purro sector, XI Corps had eliminated Shimbu by 11 June.58 Already XIV Corps had cleaned out southwest Luzon and the Bicol provinces. In a carefully planned and skillfully executed amphibious and paratroop raid, elements of the 11th Airborne Division on 23 February had liberated 2,147 Allied internees at Los Banos Agricultural

--436--

College near the southern shore of Laguna de Bay. The airborne phase of the raid, flown by 10 C-47's of the 65th Troop Carrier Squadron with 125 paratroopers from Nichols Field, was precisely coordinated with the arrival of infiltration parties; at 0700 the paratroopers dropped at the edge of the college grounds and joined infiltrators to surprise the Japanese guards at physical training before they could reach their weapons racks. Cooperating fighters strafed and bombed other parties of Japanese in the vicinity. Such was the complete surprise that only 2 Americans were killed as compared with 243 Japanese. Pushing into Ternate on 2 March, the 11th Airborne completed occupation of the southern shores of Manila Bay.59 XIV Corps could now be used for clearing southwestern Luzon and the Bicol provinces, areas held by an estimated 7,000 and 3,200 enemy troops, respectively.60

The plan of campaign called for the opening of Balayan and Batangas bays followed by an advance eastward into Tayabas and Camarines provinces. Simultaneous with the latter advance, one reinforced RCT was to land at Legaspi on about 20 March and drive northward. On 6 March the 11th Airborne Division, reinforced by the 158th RCT, launched the attack to secure Balayan and Batangas bays. Allowed to relieve the 158th RCT with the 1st Cavalry Division shortly after 15 March, the augmented forces of XIV Corps opened and secured the two bays by the end of the month.61

Plans for the Legaspi invasion were complicated by reports of a highly organized beach defense reinforced by artillery ranging up to 6-inch guns. Tentative planning arranged the overwater movement of the 158th RCT by Task Force 78, while the 515th Parachute Regiment was to be concentrated at Nichols (later Batangas) for emergency airborne employment as task force reserve. The Fifth Air Force, due to move its headquarters to Clark Field on 24 March, charged the 310th Bombardment Wing at Mindoro with aerial preparation, convoy cover, and close support for the landing and subsequent operations. The V Bomber Command was to strike targets in the area with B-24's, placing particular emphasis upon the port and beach defenses, beach mines, and defenses along Albay Gulf. B-day was postponed until 1 April since the Navy wished additional time for aerial neutralization of beach fortifications.62

Neutralization of Legaspi began on 23 March and continued with daily attacks to B-day, although the weather made fulfillment of full

--437--

schedules impossible. In order to release part of the Mindoro-based heavy bombers for missions to Formosa, XIIIBomber Command took responsibility for Legaspi between 26 and 30 March, but its 5th Group was able to reach the target only on the 26th, while the 494th Group, flying under operational control of XIII Bomber Command, was able to strike only on the 27th. The bombers and fighters from Mindoro, however, expended a total of 1,770.2 tons of demolition, incendiary, fragmentation, and napalm bombs on the town's defenses. Although Whitehead and Krueger sought to limit attacks to specific military targets, Japanese troop movements into the town reported by Sixth Army scouts forced the 310th Wing to "level" the town with a maximum effort on the 31st.

Unfortunately, several civilians were killed, but when the 158th RCT was put ashore next morning, the enemy had abandoned his defenses. Except for the carefully preserved docks, Legaspi port and the town had been totally destroyed. Only thirty to forty rounds of artillery fire were directed against the assault transports by guns which the destroyers quickly silenced.63 The Seventh Amphibious Force radioed that preliminary air bombardment had been "largely responsible" for the success of the landing.64 Progress of the 158th RCT up the peninsula, overland and by minor shore-to-shore landings, was so satisfactory that airborne reinforcements were not needed.65 During April and May it worked up the Bicol Peninsula while the 11th Airborne cleared out the area southeast of Laguna de Bay: The 1st Cavalry, turning northward around the east end of Laguna de Bay, proceeded up the coast to lighten the responsibilities of XI Corps in the Infanta area. Though evidently accepting the loss of southern Luzon as inevitable, the Japanese holed up in scattered hill positions, where they resisted bitterly, even in the face of frequent low-level air attacks called for by the ground forces. On Mount Malepunyo just east of Lipa, to take an outstanding example, the 11th Airborne by late April had surrounded the last stronghold of the Fuji Heiden (Southern Luzon Defense Force), Hill 2610, which on 29 April B Company of the 51qth Parachute Infantry was directed to seize. Since heavy casualties were expected, the 8th Fighter Group was requested to bomb the hill prior to attack, but the bombing promised to be so hazardous to the troopers (who were reluctant to pull back from hard-won positions only 400 yards from the top) that General Swing decided to cancel the strike.

--438--

His men, however, earnestly requested that the bombing be undertaken and three flights (nine planes each) of P-38's, each plane bearing two 1,000-pound bombs, hit the hill in succession. Despite the discomfort caused by concussion on the second strike, the company commander reported that his men wanted a third. As the last bomb detonated, B Company rushed forward to gain the top before 124 stunned Japanese emerged from their caves, only to be slaughtered.66 "We of the division," Swing wrote, "are proud that our confidence in Air Support has reached the point where we are willing to remain within 400 yards of 1,000 pound bombs.67 This action broke the last remaining resistance in southern Luzon, and by the middle of May the Bicol Peninsula was firmly in American hands.

In northern Luzon on the I Corps front Yamashita's Shobu force, strongest of the Japanese commands, was entrenched in the most favorable position for defense and fought a stubborn but losing campaign until the final surrender in Tokyo. By the conclusion of the central plains campaign, I Corps had forced the Japanese back along the coastal routes of northwestern Luzon and into the entrances to Cagayan Valley, but the momentum of its drive had been stopped by Japanese emplacements around Baguio and in Balete Pass. During February the 6th Division pushed patrols through the mountains to Baler Bay, thereby isolating the whole of northern Luzon. In March the 25th, 32d, and 33d Infantry Divisions edged into the mountains where, despite mass artillery and air bombardment, the Japanese fell back only ten miles.68 Japanese defenses along the northwest coastal plain were cracked during April, as a result of guerrilla attacks from the rear and a frontal assault on Baguio from the south. Col. Russell Volckmann, an American officer who had refused to surrender in 1942, had rallied an imposing but poorly armed force of some 8,000 Filipinos in the coastal mountains; given close support and airborne supplies by the 308th Wing, his force captured San Fernando on 14 March.69 After the 37th Division was brought up from Manila to reinforce the 33d Division, the two units captured Baguio on 26 April, thus opening coastal routes as far north as Vigan. The approach to that city from the west was dominated by two pieces of commanding ground, Observatory Hill and Camp Henry T. Allen Hill, both occupied by determined enemy forces. In the assault on the former, enemy forces were routed by aerial bombing and strafing, and the American infantry seized it at a cost of but one man wounded. Similarly,

--439--

in the attack on the latter hill, the infantry found that a number of serviceable heavy machine guns had been ready to fire on them from commanding positions, but the Japanese gunners had been so stunned from the preliminary air bombardment that they did not fire a shot. Some thirty enemy soldiers were found in one group, killed by concussion alone.70

During April I Corps also intensified its fighting along Highway 5 and the flanking Villa Verde trail, seeking to capture Balete Pass. Air support in this area of difficult terrain and strong opposition was available in abundance. The 25th Division, moving along the highway, reported sixty to eighty planes a day in direct support, and its 161st Infantry Regiment was helped in its advance by an average of thirty-five tons of bombs each day for the first week of May.71 The 32d Division, operating along the tortuous and twisting Villa Verde trail, was satisfied with four strikes a day, usually two in the morning and two in the afternoon. In these wooded areas, as at Ipo, napalm was effective both for burning away covering vegetation and for flushing the Japanese into the open. Other strikes caused more direct casualties: 25th Division credited attacks against ravines east of the highway on 23-25 April with killing some 400 regimental command and supply troops.72 Stubborn resistance slowly gave way under continuous pressure, and on 13 May, after a heavy air attack and artillery barrage, the 25th captured Balete Pass, gateway to the Cagayan Valley. Although slowed by the rainy season, the 32d Division had cleared Villa Verde by 27 May. The way was now open for an advance into the valley.

Electing to gamble that Yamashita had expended his best troops at Baguio and Balete, Krueger immediately decided to encircle and subdivide the enemy forces remaining in the valley. A force of guerrillas, rangers, infantry, and artillery-called the Connolly Task Force after its commander-was to proceed northward and eastward along the coastal routes to Aparri. The 33d Division wasto mop up eastward toward the valley from Baguio, while the relatively fresh 37th Division was to enter at Balete and move northward along Highway 5. Having been tied down so long to defensive positions, the Shobu force was unable to maneuver against this attack. Air action further paralyzed the Japanese: in the Ambuclao-Bokod area, northeast of Baguio in the mountains, advancing ground troops found shallow graves of more than 1,000 Japanese supply troops, apparently air and

--440--

artillery casualties. The ground soldiers called this area "Death Valley." The 37th Division drove northward to Bagabag with continuous patrols overhead and, as soon as the reinforcing 6th Division arrived to hold the juncture, continued northward toward Aparri. Working around the coastal route, the Connolly Force entered Aparri without opposition on 21 June; since it was too weak to hold the escape route, however, Krueger, who was already using air supply drops to his troops as they battled through mountainous terrain, immediately ordered a paratroop attack.73 With 3 days' warning, the 317th Troop Carrier Group, augmented by 7 C-46's of the 433d Group for towing cargo gliders, moved down to Lipa airstrip; on the morning of 23 June the group dropped 994 men of the 511th Parachute Infantry Regiment on the abandoned Japanese airdrome at Camalaniugan. Only 5.6 per cent of the men jumping received injuries, mostly minor, and as soon as the gliders slid in with vehicles, the task force was ready to move. Three days later, on 26 June, elements of the 511th Regiment and 37th Division met at Alcala.74 Except for mopping-up operations, undertaken by the Eighth Army on 1 July, the campaign for Luzon was completed.

The close support missions noted during the land campaigns were those which caused special comment by ground Commanders, but they represented no more than a fraction of the total flown by Fifth Air Force pilots in their everyday work. Often they strafed or bombed some hillside or clump of trees pointed out by a smoke shell, seeing nothing and having only the voice of the ground controller for direction. Or perhaps they followed a liaison plane down to the target and attacked where it indicated. So great was the number of such missions that for the first time in the history of SWPA the air effort became one of massed numbers. Of 26,250 fighter and bomber sorties flown by the Fifth Air Force between 28 January and 10 March, 24,373 were ground support sorties; of 13,492 tons of bombs dropped and 8,133,000 rounds of .50-caliber ammunition fired, 11,697 tons and about 8,000,000 rounds directly assisted the ground troops. By informal agreement early in March, the bomb wings undertook support of one corps each, the 308th working with I Corps, the 309th with XI Corps, and the 310th with XIV Corps. Personal contacts between ground and air commanders, together with simplified communications, facilitated effective employment of the several air elements without loss of combined strength to meet special needs.75

--441--

Air mistakes resulting in casualties to Sixth Army troops were few and limited almost entirely to the first two months of the campaign. On 29 January P-51's strafed friendly ground troops along the Pampanga River, and a Marine dive bomber accidentally jettisoned a bomb on an LSM off Damortis. On 4 February six B-25's strafed an area held by friendly troops in San Jose.76 Reactions of the air commanders to these accidents was somewhat less philosophical than those of the ground generals, one of whom spoke of having experienced short rounds from his own artillery.77 Unable to discover which P-51's were guilty at the Pampanga, Whitehead, suspecting that enemy Tonys with U.S. insignia might have done the strafing, grounded all P-51 's and sent out patrols to shoot down any encountered.78 Kenney cautioned all pilots to avoid flying over friendly vessels, and Whitehead issued elaborate instructions requiring positive identification of all targets prior to attack.79 When twenty-three Liberators, trying to bomb Japanese caves west of Stotsenburg on 22 February, mistook ground markings and bombed "9-10 miles off the target" without damage to friendly troops, Whitehead promptly relieved the group commander.80 On the other hand, there were instances of planes shot down when ground controllers sent them on as many as three dry runs through AA concentrations.81

Any final critique of the effectiveness of close support must represent the views of ground commanders. Krueger called the support rendered by the Fifth Air Force "superb" and observed that it materially assisted both in taking objectives and in holding battle casualties to a minimum.82 At the close of the campaign, the SWPA Air Evaluation Board asked ground commanders to comment upon the success or failure of air support. With the exception of one commander who declined to make any statement, the results ranged from highly satisfactory to commendatory. By common admission the greatest difficulty in close support was the problem of coordination with the ground attack, but performance had improved as communications and operations personnel acquired experience.83

At the end of the war, when Yamashita came down out of the hills to take up residence in the New Bilibid Prison, he was asked by Allied ground officers about the effect of Allied artillery and air support upon his operations. Obviously limited for the most part to his observations in northern Luzon on the Shobu front, his general comments were exceedingly reserved. On morale, the effect of air support had

--442--

not been too serious, although it "rubbed-in" the fact that the Japanese ground soldier had no protecting planes. On movement, air support had had a decided effect: when aircraft were in the vicinity, all movement ceased and even night hecklers were greatly feared. Strafing usually had not been serious, for his troops could take cover. Bombing required direct hits on scattered cave positions and was seldom more troublesome than the concussion resulting. Napalm had been of very little effect, once rains soaked the northern Luzon terrain. On materiel, air strikes had had little effect once his forces were entrenched, but any form of transport was very vulnerable. Yet, for all his reservations, Yamashita concluded: "If we had had your artillery and your air support, we would have won.84 In another interrogation concerned with his experience in northern Luzon, Yamashita expressed admiration for the close coordination of air power and artillery to protect the flanks of the attacking divisions, coordination which had made his own plan to infilter and harass impossible. "We weren't ready for that type of fighting," he summarized, "and you beat us with it."85

FEAF Moves to Luzon

The air facilities constructed for FEAF at Lingayen and San Marcelino met the requirements for an assault campaign, but neither area could support continued operations of any magnitude. San Marcelino, moreover, would have to be abandoned once the rains began in May 1945. Locations were also required for FEAF Headquarters and for the major logistics establishment to be built for FEASC.

Faced with commitments requiring AAFSWA to bomb Formosa during the Okinawa operations and needing heavy bombardment bases nearer to Luzon than Leyte-Samar, GHQ had readily agreed to Whitehead's proposal for two B-24 fields on Mindoro. Work was begun at Caminawit Point (later called McGuire Field) on 2 January, and a 7,000-foot runway was ready for use on 26 January. Without steel matting, which had been sunk, the engineers had to improvise a clay and gravel subsurface and coat the runway with gravel chips shot with asphalt. The other heavy bomber strip, Murtha Field, had been started on 27 January and its steel-mat runway was opened on 5 March. Because of subsurface difficulties it had to be reworked a little later, but the rains were late and Hill and Elmore remained usable at the time.86 During the summer of 1945 these bases would be of

--443--

value in the southern Philippines campaign. Kenney, who had called Mindoro a "gold mine," had been right.87

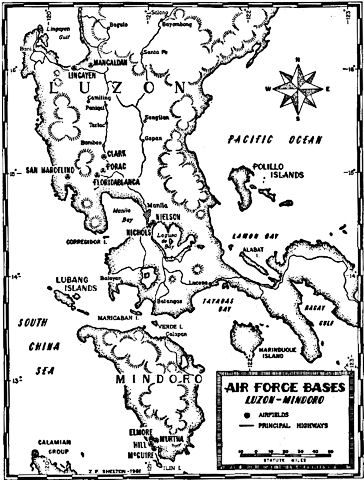

FEAF got no such ready approval for the development of all-weather bases on Lwon, chiefly because in the spring of 1945 SWPA

Air Force Bases Luzon-Mindoro

had no directive for operations subsequent to the reduction of the Philippines. In October 1944 Arnold had written Kenney about plans to base a projected XXII Bomber Command and pehaps the XX Bomber Command on Luzon.88 The B-29 project continued hot through April 1945, requiring Kenney to plan for very heavy bombardment

--444--

bases, but no definite orders came; by May base sites became available on Okinawa.89

Kenney and Whitehead were anxious to locate FEAF tactical units as far north as possible and had hoped to base both the Fifth and Thirteenth Air Forces on the northwestern coast of Luzon.90 During the middle of February GHQ directed USASOS to assume responsibility for all construction on Luzon; it promptly organized the Luzon Base Section Engineer Command (LUBSEC) with four subdistricts: the Mangaldan area, Clark Field area, Port of Manila, and south Manila area. With ground reconnaissance nearly completed, Kenney secured a commitment from GHQ on 17 February defining the Luzon air garrison, a listing of unit types which was slightly enlarged on 23 February. In general, dry-weather facilities were to be provided by 20 March and all-weather facilities by 15 May. The units specified were those of Kenney's first-phase tactical movement plus an air depot (four air depot groups). With this authority FEAF secured five all-weather airdromes: Clark, Porac, Floridablanca, Nichols, and Nielson. The first three were spread about twenty miles north and south of Fort Stotsenburg and were used by tactical units, Clark and Floridablanca having dual heavy bomber runways capable of extension for B-29's; Nichols and Nielson served FEASC's Manila Air Depot. Work began on all the fields early in March and they were practically complete in May.91

Whitehead moved tactical units into the Clark Field area as quickly as the engineers prepared runways and any sort of parking space. Air units from San Marcelino moved overland, and the Fifth Air Force established its headquarters and those of its commands at Fort Stotsenburg on 24 March. The old fort, only slightly damaged by the withdrawing Japanese, furnished the best quarters and working conditions which the air force had known north of Australia; only the 91st Reconnaissance Wing, located in the old stables, may have thought differently. Recreation was adequate for the first time since June 1944. By the end of May, the Fifth Air Force had most of its tactical units at Clark, Floridablanca, and Porac, with lesser aggregations at Mindoro and Lingayen.92

Although an advanced echelon had been opened earlier, FEAF Headquarters late in April moved into Fort William McKinley, just outside Manila, a move timed closely to follow that of GHQ, which established its command post in downtown Manila on 12 April. Fort

--445--

McKinley, unlike Stotsenburg, had been heavily fought over, and only a few buildings remained of a formerly extensive post. Most of lower-ranking headquarters personnel remained in tents until bamboo shelters were built, but streets, a water system, and a swimming pool were convenient luxuries.93

FEASC had planned to meet the needs of the Philippines campaign with its two IV ASAC depots in New Guinea, Depot No. 3 at Biak and Depot No. 1 at Finschhafen. Despite construction delays, the Biak air depot had begun operations in mid-September 1944, and early in December IV ASAC moved its command post from Finschhafen to Biak, assuming direct supervision of the repair, maintenance, and erection facilities there. During November V ASAC had tried to move its Townsville depot activities to Leyte, only to become bogged down by the rains.94 Although General McMullen thought that V ASAC showed a commendable accomplishment against the many obstacles confronting it on Leyte, he found it necessary in January 1945 to begin an expansion of the Biak air depot* to serve the Philippines95 and to look northward to Manila for a more permanent solution to his problem. Early in February he sent a scouting party to follow the fighting into Nichols and Nielson fields, tentatively committed to FEASC for its Depot No. 7, designed to become the largest of its kind in the SWPA. On 21 February an advanced detachment of FEASC with attached bomb-disposal experts and military police flew to Nichols. Three days later FEASC issued revised warning orders for the movement of the 4th (Leyte), 49th (Darwin), 12th (Townsville), and 81st (Finschhafen) Air Depot Groups to Manila between 1 March and 1 June; the Headquarters, V ASAC, and FEASC were to move forward on 1I May and 1 June.96 A usable depot was to be completed at Manila by 30 June, and all attendant facilities by 1 November 1945.97 Difficulties in securing shipping and unloading problems at Manila Bay slowed movement of service troops to Luzon. Construction supplies were short; the first depot troops began to build with materials which they had scavanged from the dumps around Nichols and Nielson. FEAF also insisted that FEASC first get a bulk of technical supplies to Manila and then worry about an orderly air depot. "I would rather have a great deal of excess supplies not properly

* The Biak air depot remained the most productive FEASC installation through July 1945, by which time it was slated for liquidation. Finschhafen was all but closed on 1 August 1945.

--446--

binned and sorted,'' admonished Col. W. H. Hardy, FEAF A-4, "than an insufficient amount completely binned and warehoused.".98

On 20 April FEASC nevertheless officially announced that the Manila Air Depot was open for supply, aircraft erection, and a limited amount of minor aircraft and equipment repair.99 During May the new depot surpassed Biak in the number of service units assigned, but its emphasis necessarily ran toward supply, with Biak and Leyte still doing most of the aircraft erection and processing of ferried aircraft.100 By August, however, Manila was about ready for the approaching end of operations at Biak.101 FEASC, having successfully kept pace with tactical air operations in the Philippines was now concerned with the development of an air depot at Naha, on Okinawa, designed to serve both FEAF and the USASTAF* during the projected campaign against Japan.

The five airfields approved by SWPA on 23 February were but part of those wanted eventually by General Kenney, but GHQ, citing the need for other essential base facilities, the shortage of engineers (80 per cent of the aviation engineers on Luzon were never used on aviation projects), and the shortage of shipping, proved unwilling to increase the Luzon air facilities. Actually, the five airfields authorized met FEAF's most pressing needs, but if it was to undertake missions to the China coast and larger attacks on Formosa, it needed another field as far north on Luzon as possible. Early in March, as soon as guerrillas had captured the area, Col. D. W. Hutchison, commander of the 308th Wing, flew food up to Laoag and got native labor working on the Japanese strip there. Brig. Gen. Leif J. Sverdrup, acting chief engineer, SWPA, agreed to lend some heavy equipment, dump trucks were borrowed from air units in the central plains, and on 22 May--the same day that GHQ issued a construction directive a 5,000-foot all-weather runway became operational. Late in April the 3d Air Commando Group moved to Laoag and assumed command over Gabo Field. With additional construction now blessed by GHQ but still under air force direction, Gabo would become a vital link in FEAF's movement to Okinawa.102

* See below, p. 692.

--447--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (13) * * Next Chapter (15)

Notes to Chapter 14