AN ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY OF

THE BUREAU OF SHIPS DURING WORLD WAR II

VOLUME II

U. S. BUREAU OF SHIPS

FIRST DRAFT

NARRATIVE

PREPARED BY THE HISTORICAL SECTION

BUREAU OF SHIP

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOLUME II

|

CHAPTER |

PART III |

PAGE |

|

|

VI. DEFENSIVE STRATEGY AND THE BUREAU OF SHIPS |

1 |

||

|

The Pearl Harbor Attack |

|||

|

The Balance of Fleets |

|||

|

The Strategy |

|||

|

The Impact upon the Bureau |

|||

|

VII. DEATH AND REJUVENATION AT PEARL HARBOR |

23 |

||

|

VIII. PERSONNEL EXPANSION |

67 |

||

|

IX. EXPANSION OF FACILITIES |

163 |

||

|

Introduction |

|||

|

The Expansion |

|||

|

Production Shortages |

|||

|

Financing |

|||

|

Types of Contracts |

|||

|

Lessons Learned |

|||

|

X. CONTROL OF THE SHIPBUILDING PROGRAM |

197 |

||

|

Overall Controls |

|||

|

Program Planning |

|||

|

Production Requirements Plan |

|||

|

Controlled Materials Plan |

|||

|

….. |

Operation |

||

|

Scheduling Components for Shipbuilding and Maintenance |

|||

|

Raw Materials Section and Its Functions |

|||

|

XI. INSPECTION |

255 |

||

|

Supervision and Inspection |

|||

|

Jurisdiction |

|||

|

Personnel and Locale |

|||

|

Post-War |

|||

|

XII. SHIP SALVAGE AND FOREIGN REPAIR |

273 |

||

|

Salvage Operations by Civilians |

|||

|

Salvage in Forward Areas |

|||

|

Foreign Ship Repair |

|||

|

XIII. SHIPBUILDING AND TURNING OF THE TIDE |

307 |

||

|

Chronology of Defensive War |

|||

|

Shipbuilding Production |

|||

|

|

Appropriations |

||

|

Planning |

|||

|

Precedence Lists |

|||

|

Problems of Production |

|||

|

Production Record |

|||

--iii--

TABLES

|

Table No. |

Page |

|

|

14 |

Balance of fleets before Pearl Harbor 1 December 1941. Major combatant vessels |

5 |

|

15 |

Personnel on board - BuShips, Navy Department; by months, 1933-1945 |

71 |

|

16 |

Number of employees by service, giving percentage of |

76 |

|

17 |

Total number of professional employees, 1941-1945, by grade |

77 |

|

18 |

Total number of sub-professional employees, 1941-1945 |

78 |

|

19 |

Total number of clerical, administrative and fiscal employees, 1941-1945, by grade |

79 |

|

20 |

Total number of crafts, protective and custodial employees, 1941-1945, by grade |

80 |

|

21 |

Number of contract employees, 1942-1945 |

82 |

|

22 |

Engineering personnel as of 1 September 1947 |

113 |

|

23 |

Distribution of Officers attached to activities under

the cognizance |

115 |

|

24 |

Officer Personnel, 1940-1945 |

118 |

|

25 |

Summary - procurement, training and assignments of |

121 |

|

26 |

Summary - BuShips Reserve Officers indoctrinated January 1943 to December 1945. |

122 |

|

27 |

Summary of Training Input, December 1942 to December 1945 |

123 |

|

28 |

Technical Officers assigned duty from Indoctrination or

|

124 |

--v--

TABLES, Cont'd

|

Table No. |

Page |

|

|

29 |

Educational background of WAVE Officers in BuShips |

136 |

|

30 |

WAVE Officers and V-10's assigned to BuShips and its Activities |

141 |

|

31 |

Number of shipyards building, repairing and converting (selected periods) |

166 |

|

32 |

Geographical list of shipyards as of 10 July 1943 |

170-74 |

|

33 |

Facilities expansion, June 1940 to November 1945 |

186 |

|

34 |

Dollar value of Certificates of Necessity sponsored by BuShips |

188 |

|

35 |

Analysis of major salvage operations under NObs 36, December 1941 to December 1945. |

284 |

|

36 |

Foreign Ship Repair |

303-04 |

|

37 |

U.S. Naval Shipbuilding Program - Authorising Acts, 1934 to 1942 |

318 |

|

38 |

Ship construction or acquisition by Authorization Acts, January 1942 to January 1944 |

319 |

|

39 |

New construction and conversions directed by CNO or SecNav, 1942 to 1943. |

329-30 |

|

40 |

Major changes in precedence of Naval vessels, 1941 to 1943 |

333 |

|

41 |

Semi-annual estimated dollar value of construction and |

357 |

|

42 |

New Construction, conversions and acquisitions by number of vessels and tonnage completed, by type, |

358 |

|

43 |

New Construction completed, 1942 and 1943 - Combatant, Mine Craft and Patrol Craft |

359 |

|

44 |

New construction completed, 1942 and 1943 -Auxiliaries |

360 |

--vi--

TABLES, Cont'd

|

Table No. |

Page |

|

|

45 |

New construction completed, 1942 and 1943 - District Craft |

361 |

|

46 |

New construction completed, 1942 and 1943 - Landing Craft |

362 |

|

47 |

Vessels and tonnage converted, 1942 and 1943 - Combatant, Mine Craft, Patrol Craft and Auxiliaries |

363-64 |

|

48 |

Total conversions and acquisitions - Auxiliaries, District Craft, Landing Craft, Small Boats, 1942 and 1943 |

365 |

--vii--

CHARTS

|

Chart No. |

Page |

|

|

VI |

Organization chart, BuShips, 23 October 1942 |

15 |

|

VII |

Personnel on board, BuShips, Navy Department, January 1940 to June 1945 |

70 |

|

VIII |

Civilian personnel in BuShips, Navy Department, by type of service, 1941 to 1945 |

74 |

|

IX |

Civilian personnel in BuShips, Navy Department, by type

of service, |

75 |

|

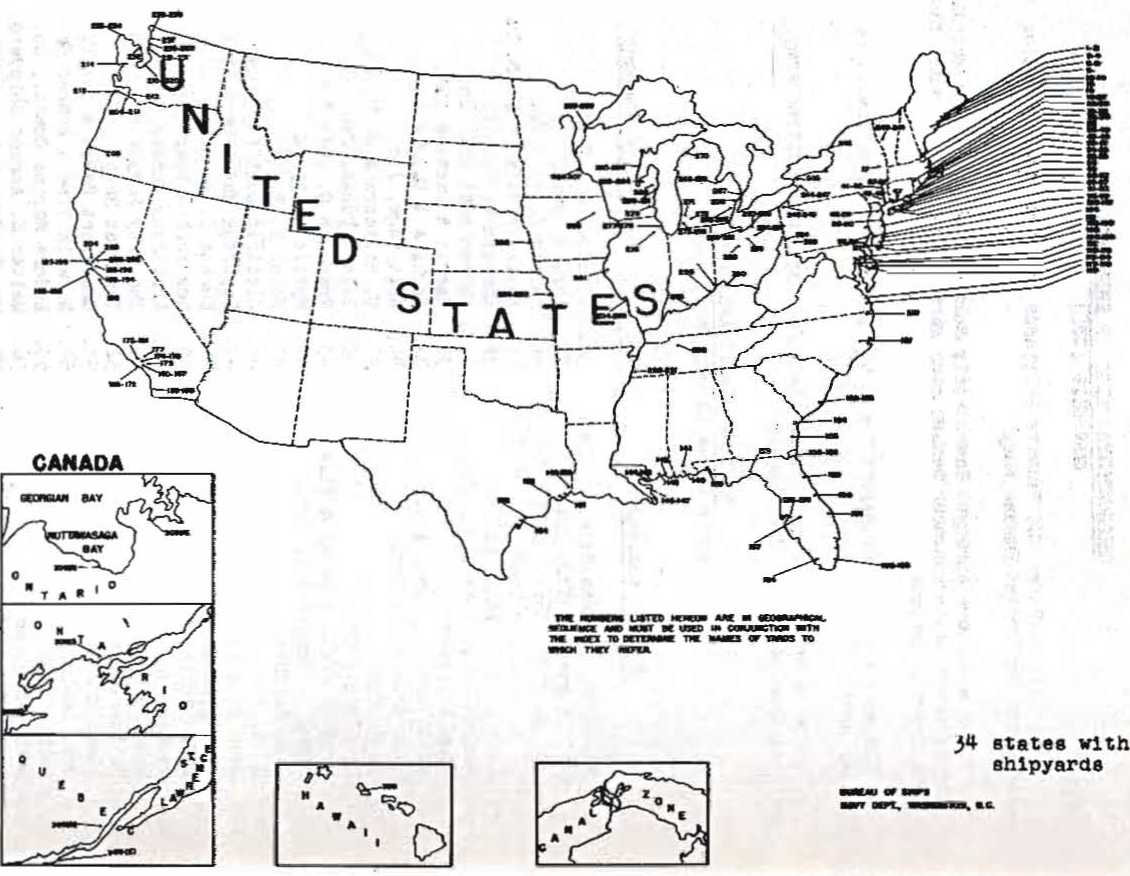

X |

Private and Naval Shipyards in geographical sequence, as of 10 July 1943 |

169 |

|

XI |

Proposed organization chart of CMP Section |

238 |

|

XII |

Tabulation showing, by quarters, controlled material

estimated requirements, |

239 |

|

XIII |

Cumulative tonnage completed of new construction, January 1942 to January 1944 |

356 |

--ix--

PART III

DEFENSIVE WAR AND TURNING OF THE TIDE

DEC, 7. 1941 - AUGUST 1943

The First 21 Months

CHAPTER VI

DEFENSIVE STRATEGY AND THE BUREAU OF SHIPS

VI. DEFENSIVE STRATEGY AND THE BUREAU

On the peaceful Sunday morning 7 December 1941, the Japanese hurled a devastating attack upon the United States Fleet based at Pearl Harbor while her representatives in Washington were still engaged in discussions, presumably in the interest of preventing war. The attack was essentially an air raid, although there were some 45-ton submarines which participated.

As will be discussed at length in Chapter VII, the primary objectives of the Japanese were clearly the heavy ships in the harbor. Our previous study of the comparative fleets and our further perusal in this chapter of the fleet at the time of the attack illustrate the Japanese reasons for attempting to balance the capital ship ratio.

Although at Pearl Harbor on that fateful morning our forces had evidenced "lack of alertness", the United States Navy throughout the world could not be accused of a state of unpreparedness.

Despite Congressional budgetary limitations, the Navy, for twenty years in its program of readiness, worked under schedules of operation in competitive training and inspection unparalleled in any other Navy of the world. Fleet problem tactical exercises, amphibious operations with the Marines and Army, aviation, gunnery, engineering, communications were all integrated in a closely packed annual operations schedule. This in turn was supplemented by special activities ashore and afloat calculated to train individuals in the fundamentals of their duties and at the same time give them the background of experience so necessary for sound advances in the various techniques of Naval warfare. Ship competitions established for the purpose of stimulating and maintaining interest were

--1--

climaxed by a realistic fleet maneuver held, once a year with the object of giving officers in the higher command experience and training in strategy and tactics approximating these responsibilities in time of war. To the technical bureaus, such as the Bureau of Ships, these maneuvers proved of inestimable value. Our peace time training operations and administrative preparations, which had involved hard work and many long hours of constructive thinking at long last were ready to pay dividends.

In other elements of our fighting strength also we were rapidly becoming more able to cope with an engagement in full scale warfare. As we have seen the so-called Two-Ocean Navy bill of 19 July 1940 provided for an expansion of about 70% in our combat tonnage - the largest single building program ever undertaken by any country. The Navy Department had already initiated expansion of Naval shipbuilding facilities in private yards and in Navy yards.

In many instances, particularly in Navy Yards, the expansion provided facilities which were to be available for repair as well as new construction. At the time of the Two-Ocean Navy bill's passage, expansion of general industry also occurred to meet the requirements of the shipbuilding program beginning with plants producing raw materials. Under such a situation did the United States find itself drawn into World War II.

--3--

I. BALANCE OF THE FLEET

However great the dynamic situation of the comparative fleet prior to 1941, this one year became the "year of decision". In a desperate effort to overcome a noticeable disadvantage, the Japanese doubled their tonnage under construction, while their major combatant vessels on hand also enjoyed a perceptible increase of over 150,000 tons. Their emphasis rested upon aircraft carriers primarily and light cruisers secondarily during this pre-war preparation.

At first glance, Japan’s naval status at the moment of the war's outbreak appeared to suffer considerable inferiority. The Nipponese fleet of 285 major combatant vessels at that time totaled approximately one and one-half million tons. Great Britain and the United States, however, possessed a combined sea power of 1,200 vessels amounting to five and one-half million tons. In light of this decided disadvantage the declaration of war by the Japanese appeared suicidal. Table 14 however may offer sane reason behind the diabolical scheme of the Japanese.

--4--

TABLES 14

BALANCE OF FLEETS

BEFORE PEARL HARBOR 1 DECEMBER 1941

MAJOR COMBATANT VESSELS

|

UNITED STATES |

||||||

|

On Hand |

Under Construction |

Total |

||||

|

No. |

Tons |

No. |

Tons |

No. |

Tons |

|

|

Battleships |

17 |

531,300 |

15 |

700,000 |

32 |

1,231,300 |

|

Aircraft Carriers |

6 |

134,800 |

12 |

320,100 |

18 |

151,900 |

|

Heavy Cruisers |

18 |

171,200 |

14 |

269,200 |

32 |

440,100 |

|

Light Cruisers |

19 |

157,775 |

10 |

368,000 |

59 |

525,775 |

|

Destroyers |

171 |

236,920 |

193 |

371,590 |

361 |

608,510 |

|

Submarines |

112 |

117,130 |

74 |

110,850 |

186 |

227,980 |

|

Total |

343 |

1,352,125 |

318 |

2,139,710 |

691 |

3,191,865 |

|

GREAT BRITAIN |

||||||

|

Battleships |

14 |

113,950 |

7 |

270,000 |

21 |

713,950 |

|

Aircraft Carriers |

8 |

161,100 |

3 |

69,000 |

11 |

230,100 |

|

Heavy Cruisers |

16 |

157,030 |

- |

- |

16 |

157,030 |

|

Light Cruisers |

50 |

313,180 |

16 |

102,500 |

66 |

115,980 |

|

Destroyers |

205 (a) |

267,489 |

69 |

117,535 |

271 (a) |

385,021 |

|

Submarines |

58 |

54,697 |

61 |

17,810 |

119 |

102,537 |

|

Total |

351 |

1,397,746 |

156 |

606,875 |

507 |

2,004,621 |

|

JAPAN |

||||||

|

Battleships |

11 |

357,000 |

1 |

15,000 |

12 |

102,000 |

|

Aircraft Carriers |

10 |

178,070 |

8(b) |

200,800 |

18 |

378,870 |

|

Heavy Cruisers |

18 |

217,000 |

- |

- |

18 |

217,000 |

|

Light Cruisers |

17 |

81,805 |

4 |

24,000 |

21 |

105,805 |

|

Destroyers |

102 |

151,605 |

22 |

11,550 |

121 |

199,155 |

|

Submarines |

71 |

107,393 |

18 |

30,027 |

92 |

137,120 |

|

Total |

232 |

1,095,873 |

53 |

344,377 |

285 |

1,110,250 |

(a)

Does not include Hunt Class Escort Destroyers, 49 of 56,703 tons under

construction and 37 of 33,460 tons built.

(b)

Includes 3 vessels of 71,000 tons in the process of being converted to aircraft

carriers.

--5--

U.S.S. WISCONSIN

Another ship under construction at the time of Pearl Harbor,

two years later is launched to owing a more favorable balance of naval power.

--6--

The British necessity of "bottling up" the German Fleet reduced the Pacific warfare to an engagement almost solely between Japan and the United States. At the same time, however, the United States were also required to maintain a supply line to Great Britain and to its expeditionary force against the Germans as well as to fight the excessive submarine warfare being waged by the Germans.

Having reasoned to this extent therefore, the Japanese undoubtedly studied the statistics as illustrated in the accompanying Table 14.

Japan had a total tonnage on hand of over 1,000,000 which the United States exceeded by only one-quarter million tons. By the end of 1941, the United States had well over two million tons under construction as compared to Japan's one-third million. The Nipponese concluded therefore that the time had arrived if they ever were to strike.

The strategy of a surprise attack being established, the problem then became one of determining upon which class or classes of ships to concentrate their blows. Table 14 depicts the relative strength of the three navies by class of ships. Although enjoying a superiority in aircraft carriers and an equality in cruisers, the Japanese suffered by comparison in battleships and destroyers. A concentration of desired targets being presented them in Pearl Harbor, the Nipponese formulated their treacherous plane and on 7 December 1941 put it into execution.

The result of this attack and the United States efforts to overcome the devastation are fully discussed in Chapter VII. The immediate effect

--7--

upon our Fleet, however, may be summarized approximately as follows:

5 battleships totalling 150,000

tons sunk

4 battleships totalling 120,000 tons damaged

5 cruisers of 26,000 tons damaged

3 destroyers totalling 4,500 tons sunk

Also damaged or sunk:

1 aircraft carrier

1 repair ship

1 floating drydock

1 tug

Whatever degree of success this attack may have seemed to the Japanese, the extent of the damage to the United States naval power was serious. In an hour of utter darkness the only light seemed to be the absence of the aircraft carriers from Pearl Harbor at the time of the attack. If the Allied inferiority in this class had been more severely jeopardized at that time, the fleet's ensuing retaliation against the enemy would have been rendered almost completely impossible.

--8--

II. STRATEGY

The comparative statistics listed above illustrate to some extent the situation facing the United States Navy as a whole and the Bureau of Ships in particular when this country was catapulted into World War II. The tremendous shipbuilding and salvage task, compounded by the European war requirements, pressed upon the newly formed Bureau a program of incredible magnitude.

Although we had made some progress, our armed forces and our production still were not adequately expanded to permit our taking the overall offensive in any theatre. In both oceans we assumed the defensive while preparations for an amphibious war were intensified.

In the Atlantic our primary concern centered upon maintaining our lines of communications to Great Britain and other bases of future operations. The Germans presented a formidable foe in their submarines and air forces in the battle for the Atlantic, while their surface forces constituted a constant threat. The United States program, therefore became one of anti-submarine or escort vessels, landing craft for the projected invasions and auxiliary vessels for supply and transport.

In the Pacific we were immediately placed on the defensive and the first task became one of halting the onrushing Japanese tide. Only after that could the turning and over-running of the tide come to pass. Expansion of the fleet in every class of ships, the development of a landing craft program, the establishment of a line of advanced bases, the emphasis upon aircraft carrier production after early battle losses which further increased our inferiority, and the extension of our submarines

--9--

into the far

reaches of the Pacific were the main elements of the overall strategy at the

war's inception.

The basis of this

strategy being based to a considerable degree upon the shipbuilding program,

the Bureau of Ships was to play a role second to none. The ensuing

chapters of this section reveal the Bureau's matter and manner of

execution of this role during the defensive and turning of the tide phases

of the war.

--10--

III. IMPACT UPON THE BUREAU OF SHIPS

Although the impact of the Pearl Harbor attack upon the Navy Department was tremendous, it apparently left responsible officers little time to concern themselves with purely organizational matters. Proposals to merge the shipbuilding and design divisions to avoid administrative difficulties, however, were discussed within the Bureau.

The urgency of the need for increased delivery of ships of all types particularly landing craft, added to the problem of defining the prospective responsibilities of the shipbuilding group interested primarily in expediting production and the design section concerned equally with matters of improvement in design to incorporate lessons learned as the result of combat operation and volume production.

Although the period prior to Pearl Harbor required responsible officers to work overtime and to overcome what often seemed to be impossible barriers to the completion of vessels or equipment, the period immediately thereafter was even more hectic and did not leave any one much time for careful consultation and coordination of his activities with all other interested groups. The result was that strong differences of opinion as to proper procedure and policies developed between shipbuilding and design. Although some sort of reorganization proved to be inevitable, the form it should take became a matter of extended controversy. An independent management survey brought to light three closely related basic organization problems:

--11--

(1) What should be the relation between the different sets of ship type desks of the Design, Maintenance and shipbuilding Divisions?

(2) What should be the proper interrelation of the ship type desk of the three divisions and the technical sections in design?

(3) What were the proper duties and responsibilities of the operating divisions, particularly the Shipbuilding Division?

The original bureau organization did not provide for the creation of ship type desks in the Shipbuilding Division, for the Development and Design Branch Desks were believed adequate to care for all plan action necessary in the building of a ship. The creation of the type desk in shipbuilding, probably justified as a means of simplifying shipbuilding responsibility for expediting, soon led to the duplication of many of the functions of the Design Desks, to the confusion and consternation of personnel in the Bureau and shipyards.

The difficulties in clarifying the relations between ship type desks and technical sections often stemmed from differences in personalities, although in this early war period the greatest pressure was being exerted on all hands for the rapid procurement of equipment and completed vessels. The type desk as organized was considered responsible for the production or maintenance of a given type of ship.

The technical desk, not concerned about types of ships but specific machines, material and pieces of equipment, did not interest itself with the progress of a particular program. This division, without very carefully established controls and procedures, led sometimes to

--12--

the duplication of effort and to overlapping as pressures developed first in one area and then another. A strong type desk head, seeing his ship delayed as the result of a failure to obtain delivery of a generator, found it difficult to accept the promise of the technical desk to expedite delivery. His natural inclination, and often his practice, was to get in touch with the manufacturer without reference to the technical desk. On the other hand, a technical desk having difficulty filling all the demands of the various type desks for a particular type of equipment might often wish and sometimes did get in touch with the various shipbuilders to establish to their own satisfaction the relative need for this equipment and to redistribute the available supply. Being the group with engineering knowledge of the equipment, they also wished to deal directly with the shipbuilder on technical, questions. The management survey believed that the ideal would be attained if type desks were the sole source of authority in dealing with the shipyard, and the technical desk the sole source of authority in dealing with the manufacturer of the material or equipment.

The final problem mentioned above is the definition of the responsibility of the Shipbuilding Division. One reason for the confusion which existed at that time was the fact that in the rapid expansion of the Bureau the Division was assigned a variety of miscellaneous activities and responsibilities that did not seem to fit into other parts of the new organisation. Thus it acquired the merchant ship conversion program, a job that functionally should have gone to Maintenance, and also a miscellaneous lot of patrol craft and non-standard boats, a job which

--13--

should have been assigned to the Design Division. Within the Shipbuilding Division, there developed a certain amount of overlapping, particularly with regard to scheduling and estimating of materials, facilities and delivery. Again, this resulted from rapid growth and new demands being placed on the Bureau as the result of the creation of the Office of Production Management and the need for better estimates and tighter controls.

A decision was finally reached on these matters and on 16 November 1942, the Shipbuilding Division and the Design Division were consolidated into a new shipbuilding division. As a part of the general reorganization, two outstanding officers were assigned to assume leadership in this unparalleled construction program. Rear Admiral (now Vice Admiral) E. L. Cochrane, USN, with an outstanding record in ship design of all classes, became Chief of the Bureau of Ships. Bear Admiral (nov Vice Admiral) E. W. Mills, USN, whose valuable experience as engineering officer in all branches of the Navy balanced so well with Admiral Cochrane's background, became Assistant Chief of the Bureau. As described in Chapter XVIII these two officers throughout the entire war provided the forceful leadership and inspiration so vitally required by the greatly expanded Bureau. Also, at this time it was decided that the great expansion in the volume of work in the fields of radio, radar and underwater sound justified the granting of division status to the former Radio and Sound Branch of the Design Division.

This resulted in the organization, presented in Chart VI.

--14--

--15--

During 1942 the problem of scheduling and materials control became one of paramount importance. The general shortage of materials and over-taxation of industrial resources made it essential that the Bureau be able to determine with accuracy its needs for material and equipment as determined by shipyard production schedules. The establishment of the Controlled Materials Plan by the War Production Board (described in detail in Chapter X) precipitated the issue and delegated to the Bureau of Ships many new functions, particularly the preparation of detailed requirements for controlled materials and the allotment of materials under CMP.

In peacetime, when materials, facilities and labor were abundant, the Navy and the Bureau could decentralize detailed shipbuilding and component scheduling to contractors and manufacturers. Under war conditions neither contractors nor the Navy had full control of the planning and scheduling of ship programs. These programs competed with Army, aircraft, Maritime, Lend Lease, civilian, and other needs for materials, machines and men, there not being enough to go around. The problem faced by the Bureau therefore was new, both in magnitude and in complexity. Under the conditions prevailing in 1942 and 1943 planning and scheduling work in the Bureau proved of critical importance.

These new developments required an unusual expansion of personnel. The Scheduling and Statistics Section of the Shipbuilding Division, the central planning and statistical control activity, assumed major responsibility for the operations of CMP in the Bureau of Ships. In the Construction Branch of the Shipbuilding Division and in the Maintenance Division, however it

--17--

also became necessary to assign personnel for the purpose of handling certain specialized functions and of preparing basic data to be processed by the general statistical control group. Major type desks had from one to five persons working on scheduling, statistics and reports while from one to seven persons worked on expediting and progressing.

Technical desks had to make similar provisions to fulfill their duties.

By March 1943 the Shipbuilding, Maintenance and Radio Divisions of the Bureau of Ships had a total personnel of 3919 people. Of these 435 were on materials estimating and allotting, 587 on scheduling, statistics and reports, 278 on progressing and expediting, and 2619 on design and other activities of the Bureau.

In effect, one employee in every three of the Bureau was involved in planning, scheduling, statistical, progressing and expediting work,

Of the total of 1300 people so employed, 718 or well over half were in the Scheduling and Statistics Section. This latter figure compares with a corresponding total of 162 employees at the end of April 1942.

The expansion of the planning and control functions of the Bureau indicated above is a reflection of, first, the stage of development of the shipbuilding program and, second, the major role of the Bureau once the shipbuilding program had gotten under way. By early 1943 ships of all types building and converting had reached a point close to the peak production load of which American industry was capable. In February 1943, slightly less than seven millions of tons of vessels were under construction. (The peak period reported was reached in January 1944, when something over 8,600,000 tons of vessels of all types were

--18--

building or being converted.) Another reason for the tremendous expansion in work load was the extreme urgency of certain critical programs requiring the tightest possible control. First landing craft and then destroyer escorts were required for vital military objectives, and in such quantities that all possible energy had to be devoted to the procurement of the many thousands of items of equipment.

The expansion of the Bureau organization responsible for control and expediting of the program also reflected organizational changes within the department, as in January 1942 the Office of Procurement and Material had been established under the direction of Vice Admiral S. M. Robinson, former Chief of the Bureau. Functions and procedures of the Office of Procurement and Material are the subject of a separate history; however, its existence and reports required by it affected the type of organization which was established within the Bureau. Liaison with the War Production Board and other procurement agencies was centered in the Office of Procurement and Material, and the important function of representing the Navy's interests before the Requirements Committee of the War Production Board was delegated to the O.P.&M.

Another important development arising out of departmental change was the creation of a new legal office in the Bureau. The procurement Legal Division of the Under-Secretary's Office, established under the administration of H. Struve Hensel in August 1941, promptly assigned a special attorney representing that office to the Bureau of Ships. Prior to this addition, the only legal group in the Bureau existed in the Contracts Branch, which was staffed solely by officers with limited commercial legal experience. In a relatively short space of time the new representative of the Secretary's Office

--19--

added to the Bureau staff experienced lawyers to advise negotiating officer.

The next major step was the creation of the Officer of Counsel for the Bureau of Ships. On 13 December 1942 the Secretary of the Navy directed a general reorganization of procurement procedures in the Navy Department. This reorganization granted the Chief of the Bureau of Ships discretion to determine the extent to which contracts would be prepared and executed in the Bureau of Ships and the extent to which the services of the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts would be used for the negotiation, preparation, and execution of contracts. Prior to the 13 December 1942 directive procurement of materials under the cognizance of the Bureau of Ships had been divided between it and the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts. The Bureau of Ships made and executed directly the greater portion of negotiated contracts, at least in respect to money value, for such subjects as major and minor combatant vessels, auxiliary, patrol craft and landing craft, yard and district craft, shipbuilding and manufacturing facilities, main propelling machinery, design services, expediting services, and salvaging services. However, the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts did prepare and execute a large number of contracts for such materials, equipment, and small boats as were initiated by this Bureau and the various continental Navy Yards, but this arrangement gave rise to inconsistencies and delay. A clear line of demarkation for those contracts which were to be negotiated by the Bureau of Ships and those which were to be delivered by the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts did not exist. Frequently the same contractor held separate contracts with the two Bureaus for the same type of article. The differences in contract administration

--20--

inevitably resulted in considerable confusion.

The discretion granted the Chief of the Bureau to extend the field of the Bureau of Ships direct procurements was exercised cautiously. By mid 1943 auxiliary equipment for new construction, materials to repair battle damage and contracts covering the repair and alteration of naval vessels been added to the contracts normally negotiated directly by the Bureau of Ships and the Bureau of Supplies and Accounts vas left only the preparation and execution of contracts covering purchase of stock materials, including those covered by annual contracts, non-urgent items of equipment for normal maintenance, personal service contracts, and equipment and materials commonly purchased by more than one Bureau, although under the primary cognisance of the Bureau of Ships, such as radio, radar, and sound material and equipment. This division afforded a clear line of demarkation which accelerated the procurement of those items primarily involving technical consideration and where time was of the greatest importance.

The organization of the Office of Counsel in the Bureau of Ships had other beneficial effects. Prior to the reorganization, procurement legal services were the responsibility of three distinct organizations, viz: The Procurement Legal Division of the Office of the Under Secretary, the Office of the Judge Advocate General, the Contract Branch of the Bureau of Ships. Under this system the approval of as many as eight attorneys was required for contracts and other legal documents. The Office of Counsel officially established by Administrative Order on 18 June 1943 centralized within the Bureau all matters of legal procurement. The rescinding of orders and directives requiring the reference of the Judge Advocate General definitely reduced the time

--21--

required to prepare, execute and distribute negotiated contracts.

The other major action taken within the Bureau was to designate the Finance Office of the Administrative division a separate Division on 9 February 1942. Administratively this action affected the other parts of the Bureau slightly, if at all, and was presumably justified by the reduction of the burdens placed upon the head of the Administrative Division and the increase in prestige accruing to the head of the Finance Division in negotiations with Congressional Committees, the Bureau of the Budget, and other parts of the Bureau and Navy Department.

Although minor changes also took place which tended to strengthen the organizational structure, the above modifications proved the major ones during the first half of the war.

--22--

CHAPTER VII

PEARL HARBOR

DEATH AND REJUVENATION

CHAPTER VII

DEATH AND REJUVENATION AT PEARL HARBOR

A. WAR.

On 7 December 1941 the premeditated, murderous Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, intended to cripple American naval power, hurled the United States into World War II against the Axis powers. Before the fires had died at the scene of the catastrophe, key naval and civilian personnel were flying to Pearl Harbor to meet under the administrative command of Admiral Nimitz, Commander in Chief, Pacific Fleet, to determine the damage suffered by the attack and to lay plans for the salvage and repair.

Captain Edvard L. Cochrane, future Chief of the Bureau of Ships and then assistant head of the Bureau’s Design Division, accompanied the Secretary of the Navy, the late Frank Knox, to Pearl Harbor. After grave consultation, the higher brackets of command devised an overall salvage and repair, plan, the Bureau of Ships being the principal technical bureau concerned.

All activities endorsed the appointment of Captain Homer N. Wallin, U.S. Navy, an Engineering Duty Only officer and at that time Fleet Salvage officer, to assume complete charge of salvage work at Pearl Harbor.

Because of its factual content and excellent historical summary of the situation, Captain Wallin's report on the problems presented and how they were conquered in the salvage of the damaged ships is quoted in full from the December 1946, issue of "The United States Naval Institute Proceedings".

--23--

B. REJUVENATION AT PEARL HARBOR

Disaster to General MacArthur’s land and air forces in Leyte would certainly have come if the Japanese Fleet had not been decisively defeated by American Naval forces in the Battle for Leyte Gulf in October, 1944. It was a narrow squeak, but the final outcome was the utter rout of the Japanese sea forces. Hirohito’s ships suffered such destruction and damage that never again could they be assembled as a major fighting force.

A most striking aspect of the battle occurred at Surigao Strait where the southern prong of the Japanese Fleet was met and destroyed by the American Seventh Fleet.

It was a matter of great satisfaction to many Americans, and it must have been a bitter pill for the Japanese, to realize that five of the six battleships of the force which thus polished off the Sons of Heaven had been damaged at Pearl Harbor on December 7, 1941.

Several of those Pearl Harbor battleships had already taken part in the landings in the Aleutians, at Tarawa, and in the Marianas; one had fought through the Normandy landings; all were yet to contribute mightily to the capture of Iwo Jima and Okinawa. Thus before the war ended nearly all of the ships which were sunk or damaged on December 7 came back to avenge in fullest measure the Japanese treachery at Pearl Harbor.

Regarding the salvage and repair of the vessels sunk or damaged at Pearl Harbor, there has been much misunderstanding in the public mind. Indeed, the public has for over four years thirsted for authentic information on every aspect of Pearl Harbor. Many persons have wanted to know details of torpedo and bomb damage, and specific causes for the sinking of our ships. Others, and especially those with a technical bent, have desired some knowledge as to methods of refloating and rehabilitation.

A Committee of Congress has explored most exhaustively what occurred before the events of December 7, without enlightening the public fully on many controversial points. The review of any disaster usually discloses that the facts which precede it are confused by views and opinions in great number and intensity, and the separation of fact and opinion becomes increasingly difficult with the lapse of time. Pearl Harbor was no exception.

--24--

After the fire - Battered by aerial torpedoes and bomb hits, the 31,800

ton U.S.S. WEST VIRGINIA (nearest ship) rests on the bottom of Pearl Harbor.

Fire following the explosions as well as oil flames from the nearby sunken

U.S.S. ARIZONA added extensively to the damage. Note the wrecked scout

plane topside of gun turret at right and the overturned plane in the right hand corner. U.S.S. TENNESSEE is in the

Background.

--25--

86 SHIPS PRESENT - 9 WERE SUNK

What occurred during and after the attack is much more factual. We know, for instance, that out of a total of 86 naval vessels in the harbor during the attack only 9 were sunk and 10 others were damaged severely. True, five of our battleships and one large target ship rested on the bottom of the harbor which was dredged to a depth of about 40 feet; three destroyers were sunk in drydock. The total count by number, type, and nature of damage was as follows:

ARIZONA, battleship, struck by one torpedo (possible) and about eight bombs of various sizes. One large bomb, of about 2000 pounds armor-piercing, apparently entered the powder magazines forward and caused the virtual disintegration of the forward half of the ship. A terrific oil fire burned for two days. Inasmuch as the torpedo hit has not been confirmed, it is likely that the Arizona was destroyed by bombs alone.

OKLAHOMA, battleship, struck by about four aerial torpedoes causing a very rapid inflow of water which resulted in the capsizing of the vessel within about eleven minutes.

The ship rested on the bottom at an angle of 150° from upright. Only a small segment of the bottom and the starboard bilge were visible above the water.

CALIFORNIA, battleship, was struck by two aerial torpedoes and one bomb. Another bomb which was a near-miss exploded close aboard and opened a large hole in the ship's port side. Another near-miss fell off the starboard bow but caused only minor damage. The CALIFORNIA stayed afloat for over three days but gradually settled until her main deck aft was about 17 feet under water.

WEST VIRGINIA, battleship, was struck by 7 aerial torpedoes and 2 bombs. The ship sank rapidly and rested on hard bottom. Fire damage throughout the ship was severe.

NEVADA, battleship, was struck by one aerial torpedo and five bombs of various sizes. The vessel was able to get underway but the continued inflow of water necessitated beaching her near the entrance channel to Pearl Harbor. She was severely damaged by fire.

UTAH, an old battleship used as an aerial target, was probably struck by three torpedoes. The vessel capsized and came to rest on the bottom 165 from the upright position.

--26--

PENNSYLVANIA, battleship, was in drydock and was struck by one medium-sized bomb which caused considerable topside damage and a number of personnel casualties.

MARYLAND, battleship, was struck by two bombs forward which caused considerable flooding and trimmed the bow down about five feet.

TENNESSEE, battleship, was struck by two large bombs which caused minor damage to one turret and several major caliber guns. The limited damage was due to low orders of detonation. The ship suffered serious damage aft due to oil fire on the water near the ARIZONA.

HELENA, light cruiser, was struck by one aerial torpedo which caused destruction of about half of the main machinery, and considerable flooding.

OGLALA, minelayer, was struck by the pressure wave from the explosion of the aerial torpedo which hit the HELENA. The side of this 40-year old vessel was opened up, and uncontrolled flooding caused her to capsize and lie on her side in 40 feet of water.

HONOLULU, light cruiser, suffered side damage from the near-miss of a medium-sized bomb, causing considerable flooding and damage to electrical wiring.

RALEIGH, light cruiser, was struck by one aerial torpedo amidships which destroyed about half of the main machinery. One bomb hit aft caused extensive flooding.

VESTAL, repair ship, was. struck by two bombs causing considerable local damage and serious flooding aft.

CURTISS, aircraft tender, was struck by one large bomb, which caused serious local damage. Also, one Japanese plane which had been hit by anti-aircraft fire crashed into a crane of the Curtiss and caused some damage.

SHAW, destroyer, was struck by three small bombs which caused great damage including the blowing up of the forward magazines, thus wrecking the forward third of the ship. The vessel was on a floating drydock at the time of the attack.

FLOATING DRYDOCK NO. 2 was struck by five bombs which destroyed its water-tight subdivision and caused it to sink to the bottom together with the destroyer SHAW and the small yard tug SOTOYOMO.

--27--

Wrecked U.S.S. DOWNES (DD-375) at left and U.S.S. CASSIN (DD-372) at right. In the rear is the U.S.S. PENNSYLVANIA (BB-38) 33,100 ton flagship of the Pacific Fleet, which suffered only light damage and was repaired after the attack. Main and auxiliary machinery fittings of the DOWNES and CASSIN are being transferred to new hulls.

--28--

CASSIN and DOWNES, destroyers, were docked abreast of each other in a graving drydock. These vessels were struck by three small bombs which exploded on the bottom of the drydock. Hundreds of fragments caused very extensive damage to the hulls and started oil fires which grew to great intensity. The combination of bomb explosions, oil fires and flooding caused the CASSIN to fall off the blocks and against the DOWNES. The first appraisal indicated that these two vessels were total losses.

TYPE AND INTENSITY OF JAPANESE ATTACK

From the general description of damage listed above, it will be noted that severest damage was suffered by the battleships and that most of such damage resulted from aerial torpedoes. It is clear the Japanese strategy was to cripple the backbone of the American Navy and that they had adapted the aerial torpedo for use in shallow waters to a degree which made it indeed a lethal weapon. It is interesting to note that the aerial torpedo was an American invention which came back to bite us. Likewise the Japanese used dive bombing, another American development, very successfully against our ships.

It is fortunate that none of our few aircraft carriers was present in Pearl Harbor at the time of the attack, as later events proved the dire need for and the extreme shortage of vessels of this type. The Japanese claimed the sinking of a carrier at the berth occupied by the UTAH - they knew that the SARATOGA was usually moored there when in port.

From Japanese sources the fact has now been established that the attack on Pearl Harbor was made in great strength.

The naval force which eventually launched its planes about 200 miles north of Oahu consisted of 6 aircraft carriers, 5 battleships, 30 destroyers and a few auxiliaries. The Japanese have stated that they launched 361 planes, of which all returned except 27. The armament carried by these various planes is not at present a matter of record. It is known, however, that every plane had a specific mission. A large number were assigned to bomb and put out of commission allair fields in the Hawaiian Islands, such as Hickam, Ford Island, Bellows, Kaneohe, and Ewa. Of the planes assigned to attack naval vessels in the harbor, a large proportion no doubt were armed with torpedoes having large explosive charges.

--29--

JAPANESE MISSION AT PEARL HARBOR

The real objective of the Japanese was to cripple the American Fleet, but the first requisite was the destruction of all American air power on the Hawaiian Islands. This latter was accomplished to an extent which seemed unbelievable to officers of the Fleet. For example, when the writer inquired of a fellow officer on the CALIFORNIA why our aircraft were not attacking the Japanese' bombers swarming overhead, the answer was that ours had all been destroyed on the ground, which was almost a factual statement.

It was ascertained from some of the Japanese planes which were shot down that each pilot had specific instructions and a very clear chart of Pearl Harbor indicating to him the target he was to attack. It might be mentioned that these charts were essentially correct even as to location of specific ships, thus indicating the accuracy of Nipponese espionage -which of course was impossible to prevent in view of the terrain and other considerations.

Naturally the Japanese, even with the large number of planes at their disposal, could not attack all targets which were of major importance. For instance, no attack was made on the extensive facilities of the Navy Yard except in the case of two drydocks which held several ships. No real damage was suffered by the large array of shops and work facilities for repairing ships, which proved of such tremendous value to the nation from December 7 onward. Likewise, the tremendous oil stowage adjacent to Pearl Harbor was not attacked at all, and it was wondered why the Japanese failed to drop at least a few bombs which might have started a conflagration that would have proved disastrous, especially to the mobility of the undamaged vessels of the Fleet in the days to follow December 7.

MURDER IN THE FIRST DEGREE

Aside from the material damage to our Fleet, the Japanese were successful in accomplishing the premeditated murder of nearly 3,100 Navy men at Pearl Harbor on that typically beautiful Hawaiian morning of Sunday, December 7. Additional lives were snuffed out elsewhere in the Hawaiian Islands, particularly at air fields and in civilian areas. Several unsuspecting civilians who were flying their personal aircraft that morning were shot down by Japanese war planes.

Unlike most occurrences of the calamitous nature there apparently was nobody who could say "I told you so." The savage and unprincipled act of a leading world power came as a wholly unexpected shock. A thing deemed impossible in this age of enlightenment and peaceful purpose had actually occurred. To

--30--

most persons it seemed like a horrible dream from which one struggles to be released by waking. But waking consisted of a gradual realization of the fact that the stealthy Japanese had been successful in seriously crippling our sea and air power and murdering a large number of our nationals.

Some critical comment has been passed to the effect that personnel engaged in national defense should have anticipated such an attack from the Japanese. Well, as an afterthought it is always easy to see where persons might have acted differently or thought differently. But in this case our military personnel, and civilian too in Hawaii, had approximately the same viewpoint toward the Japanese problem as did the whole American people. That viewpoint is hard to describe but included the fallacious conclusion that the Japanese were trying to get along peaceably in the world and that they would shrink from warring against a country as powerful as ours. The vicious thing which occurred was not within our horizons of thought; such an outrage simply "could not happen here."

DESTRUCTION AND FIRE

Torpedo and bomb explosions wrought much damage and initiated fires of great intensity. Tons of fuel oil were loosed on the water and burned furiously as the stiff trade wind shifted it from one end of the harbor to the other. The dense smoke from the conflagration on and around the ARIZONA was visible for many miles.

The harbor was soon filled with debris from sinking and damaged war ships; many injured small boats were adrift. Fragments of Japanese aircraft also littered the harbor. The whole sky over the harbor was dotted with shell bursts from our anti-aircraft guns. Some vessels, like the ARIZONA, sank to the bottom very rapidly; others responded to the valiant efforts of their crews to keep them afloat. Some ships showed serious lists due to acute damage. The OKLAHOMA capsized through an arc of 150° within ten or twelve minutes after the attack began; the UTAH was more leisurely.

OUR SHIPS STRIKE BACK

The Japanese attackers were brought under anti-aircraft fire almost immediately, — as soon as it was realized that the Japanese had struck with lethal intent. In accordance with Fleet instructions all ships had certain guns manned and ammunition at hand. Prompt action was taken to man other guns and to start the flow of ammunition. On some ships this was

--31--

impeded by the damage suffered in the initial stages — damage such as severe flooding, listing, oil fires on board, loss of power and light. Oil flooding within the ship was a great handicap because of deadly fumes and impossible footing on inclined linoleum decks. In spite of all obstacles and although suffering from the shock of extreme surprise, the ships' personnel gave a magnificent account of themselves. Their anti-aircraft fire was reasonably accurate and effective. It was estimated at the time that approximately 40 Japanese aircraft were shot down at Pearl Harbor, as against the later Japanese statements that 27 failed to return.

Although rocked back on their heels, our sailormen quickly rose to the occasion and demonstrated the traditional American fighting spirit. Deeds of great valor and self-sacrifice were commonplace. Every person devoted his full efforts toward fighting off the enemy, saving the stricken ships, fighting fires, alleviating suffering, and rescuing shipmates. The nation and the Navy may well feel proud of the manner in which the crews of our warships conducted themselves.

Space does not permit the recording of the many outstanding examples of heroism and sacrifice. However, on one battleship an officer busied himself pushing the smaller person through a 12-inch airport while he remained trapped and went down with the ship. When the Oklahoma capsized it was soon ascertained from hammer signals that a considerable number of persons were trapped in the bottom compartments of the ship, such compartments then being above water or within air bubbles. A rescue group was immediately organized to free as many men as possible. Holes were cut in the exposed bottom of the Oklahoma mostly by hand tools to release these men. In this manner men were rescued from certain death over a period of 36 hours.

ONE TASK FORCE AT SEA

It might be mentioned that at the time of the action at Pearl Harbor the Pacific Fleet was divided into three task forces and that it was customary for one or two task forces to be at sea in conformity with a drastic training schedule. Such schedules included war games in which one task force might be pitted against another. Thus there was always one task force at Pearl Harbor for refueling, supplies, recreation, and rest. This latter part of the schedule was of course essential as personnel must have a reasonable amount of rest and recreation to forestall staleness in training. On December 7 it happened that two task forces

--32--

were at Pearl Harbor and only one task force at sea. Possibly the Japanese had access to information regarding the Fleet schedule -- or possibly it was merely luck on their part that they found two task forces available as targets. Regardless of the amount of information which might have been in possession of the Japanese, the fact is that one task force composed essentially of cruisers was at sea. This task force immediately set out to the westward in search of the enemy with the purpose of attacking and destroying him. However, we now know that the Japanese task force lay to the north of Hawaii and therefore was not sighted. As we now look back on the early days of the war it seems fortunate that our task force failed to contact the Japanese, for the greatly superior strength of the enemy task force might have caused us such losses as to greatly delay, if not prevent, the magnificent performance of our small Fleet in the dark months following the attack on Pearl Harbor.

EARLY ESTIMATE

OF THE SITUATION

The prompt arousal of the natural fighting spirit possessed by Americans following the shock of infamous attack was paralleled by immediate action toward ship repair and ship salvage. The splendid organizational procedure which pervades our Navy was brought into full play at once. The higher brackets of command were furnished from various sources well-considered estimates of the situation as regards extent of damage, time required for repairs, prospects of salvage, etc. The purpose of the high command was to accomplish the following:

(a) To make immediately available to our intact task force at sea all of the undamaged or lightly damaged warships in

Pearl Harbor.

(b) To complete at

the earliest possible date the regular overhauls which had been underway

on a number of vessels assigned to the Navy Yard, Pearl Harbor.

(c) To expedite

repair of damages to ships not too badly hurt in order that they might be ready

to fight at the earliest possible date.

(d) To lay out a

long-range program for the refloating and rehabilitation of vessels which had

been sunk or seriously damaged.

The overall purpose was to handle the program of rehabilitation so as to insure being able to live up to the Navy’s high standard "of doing most with what we have" at

--33--

any particular moment. In compliance with this program the ships with minor damage received first attention and were given the utmost priority.

Any estimate of the situation following a disaster or conflagration is almost certain to be pessimistic — this for the reason that superficial evidence thrusts itself before the eye and covers up values which are hidden underneath. Pearl Harbor was no exception, as was proved later.

First appraisals indicated the total loss of several ships which were later raised and saved and others from which the bulk of the machinery and equipment were salvaged and reinstalled in new hulls. However, it is interesting to note that the first official release of information to the public regarding the losses suffered at Pearl Harbor appeared overoptimistic to persons on the spot. When the President gave the American people in a radio address on February 24, 1942 the list of ships which were lost, it seemed highly improbable that the list would work out to be that short. The President’s statement, however, was accepted as the directive of the Fleet in connection with salvage and rehabilitation. Within four or five months the salvage work had proceeded so favorably that it was clear that the President’s list of losses could not only be met but considerably shortened.

START OF SALVAGE OPERATIONS

Salvage and rescue work began immediately following the attack, as was necessary to keep ships afloat and to prevent them from capsizing. Ships' crews worked day and night in damage control parties to prevent the spread of flooding, to reduce lists, to jettison topside weights, to fight fires, and to make essential repairs to keep ships' machinery and equipment in operation. Aid and assistance were furnished from other vessels, particularly repair ships and tenders. Civilian personnel from the Navy Yard lent a hand, as did other civilian personnel drawn from contracting firms.

Tugs like the ORTOLAN and WIDGEON which had great pumping capacity were invaluable. Other small craft aided wherever practicable. The lowly garbage lighter YG16, sometimes nicknamed the "Violet", won commendation for its 36-hour vigil fighting oil fires.

The VESTAL and RALEIGH -- While the officers and crews of all ships applied themselves to their jobs in accordance with the best traditions of the service, mention should be made of the VESTAL and the RALEIGH as outstanding cases of successful damage control work and consequent self-

--34--

preservation. The VESTAL, a repair ship, was tied up alongside the ARIZONA when the attack began. This ship was struck by several bombs and eventually the Commanding Officer was blown overboard from the bridge by the concussion of severe explosion on the ARIZONA. He swam back to his ship, got her underway, and successfully beached her to prevent sinking. For his valor this plucky officer was awarded the Congressional Medal of Honor. Later he commanded the heavy cruiser SAN FRANCISCO and was killed by Japanese shellfire in the night Battle of Guadalcanal.

The RALEIGH also put up an ideal fight for self-preservation. Due to torpedo and bomb damage a large portion of the vessel was flooded and she was in imminent danger of capsizing. Every measure and artifice known to damage control personnel was utilized to keep her afloat and upright, including the removal of many topside weights, many of which were thrown overboard but recovered later by divers.

The CALIFORNIA. — The damage to the CALIFORNIA was extensive, but strenuous efforts were made to keep her afloat. At one time it seemed probable that she might capsize as had the OKLAHOMA and UTAH, but this was prevented by appropriate remedial action by the Commanding Officer and the damage control organization. It was only the lack of adequate pumping capacity which prevented saving the CALIFORNIA. In spite of valiant efforts the flooding of the ship gained headway and soon all power on the ship was lost due to general flooding and to heavy smoke in the fire rooms. This originated from a serious fire on board. After three days the ship finally sank and rested on the bottom. It had been predicted that the soft nature of the bottom would not support the weight of the vessel and that she probably would sink out of sight. Fortunately, however, the CALIFORNIA finally stopped sinking when her main deck was about 17 feet underwater and with a list to port of 5 1/2 degrees. No more strenuous effort was ever made to keep a vessel afloat. It was a source of touching gratification to witness the deviated efforts of the young Americans comprising her crew as they stayed on their jobs for three days with little or no opportunity for rest or to remove the fuel oil with which they were smeared. For most of them their bill of fare for the period consisted almost entirely of sandwiches and coffee.

ORDNANCE MATERIAL — On December 7 a start was made in removing from severely damaged ships all of the anti-aircraft guns which could be more advantageously used elsewhere, and also ammunition and ordnance material such as range finders, spotting glasses, etc. There was a dearth of such material in the Hawaiian area, particularly around air fields, and it was therefore a welcome relief to see anti-aircraft guns installed

--35--

around the Navy Yard and the Army’s Hickam Field.

INITIAL REPAIRS -- While preliminary salvage work proceeded, plans were developed for major salvage operations. At the same time repairs on damaged vessels were being prosecuted vigorously by all hands, particularly at the Navy Yard. The battleships and cruisers which were not severely damaged were put into condition to make them seaworthy and able to fight within a short time. Other vessels were drydocked for temporary repairs to permit passage to the West Coast navy yards for final repairs and installation of machinery and equipment which had been destroyed.

It should be understood that the many vessels which had not been damaged in any way, particularly destroyers and submarines, had put to sea following the attack, or as they were readied and supplied for offensive operations against the enemy.

SCHEDULE OF REPAIR WORK

On the basis of repairing ships in inverse order to the amount of damage suffered, the following schedule of repair work was carried out:

(a) There were three battleships which had received damage which could be repaired in a reasonably short time.

The Commander in Chief was particularly anxious to expedite repairs on these battleships in order to get them to sea.

All essential work was finished in about three weeks, consisting mainly of the following:

(1) The PENNSYLVANIA required replacement of one 5 inch 25 caliber anti-aircraft gun which, together with its foundation structure, was destroyed by a 500-pound Japanese bomb. A similar gun was removed from the WEST VIRGINIA and installed on the PENNSYLVANIA.

(2) The MARYLAND received two bomb hits on the forecastle. One of about 100 pounds exploded on the main deck and caused miscellaneous small damage affecting the watertightness of the forecastle deck. The second bomb of about 500 pounds passed through the port side of the ship about 12 feet under water and exploded in a storeroom near the keel. This explosion destroyed flats and bulkheads in the vicinity, and the fragments opened numerous leaks through the bottom and shell and scattered stored materials everywhere. It was an onerous job to stop these various leaks without going into drydock but inasmuch as the drydocks were at a premium the repair work on the MARYLAND was of a

--36--

temporary nature. The effort was successful and the 5 or 6 foot trim by the head was corrected, but not without a very trying time.

(3) The TENNESSEE was hit by two large bombs, probably of the 15-in. shell type. One passed through the armored top plate of No. 3 turret. Fortunately, it was a dud and caused no serious damage. The other struck the center gun of No. 2 turret and caused a large crack which would necessitate the replacement of the gun. The most serious damage suffered by the TENNESSEE resulted from the continuous oil fires around her stem adjacent to the burning ARIZONA. In spite of all precautionary measures the heat started serious fires aft which spread forward as heavy layers of paint reached ignition temperatures.

Much of the hull plating became warped and some of the riveted joints were badly strained. Electric cables, including the degaussing lines, were burned out. Repairs were accomplished by working parties from repair ships and from the Navy Yard.

One of the most serious circumstances regarding the TENNESSEE was that she was wedged tightly between the sunken WEST VIRGINIA outboard and the concrete quay inboard. It was possible to move her only after the quay had been removed by successive applications of dynamite. Some damage to the TENNESSEE'S port side at the turn of the bilge resulted from contact with the bilge of the West Virginia as she settled to the bottom after pivoting on her torpedoed port side.

(4) The crew of the VESTAL did an excellent job in accomplishing repairs to the damages caused by two bombs. As in the case of the MARYLAND, the bomb exploded in a storeroom in the bowels of the ship. After about ten days pumping and removing of damaged material it was possible to accomplish temporary repairs, which permitted the vessel to remain fully afloat. When the dry dock schedule at Pearl Harbor relaxed somewhat, the VESTAL was sent in for permanent repairs.

(5) The crew of the RALEIGH, as heretofore mentioned, did an excellent job in keeping their ship afloat. The one bomb which hit aft did not explode but penetrated three decks and the ship's side aft. Temporary repairs to this damage were accomplished by the ship's force. Later the RALEIGH was docked and permanent repairs in way of the torpedo hit were effected by the Navy Yard. Thereafter the RALEIGH returned to the mainland for installation of new machinery and equipment to the extent required.

(6) The floatability of the CURTISS was in no way affected, but there was considerable topside damage from bomb fragmentation and from the gasoline fire caused by a Japanese

--37--

airplane colliding with the starboard boat crane. The ship's crew went a long way in repairing the damages, which were eventually made good by the Navy Yard.

(7) The HONOLULU was tied up at a Navy Yard pier. One bomb of about 500 pounds struck and passed through the pier and exploded in the water alongside the HONOLULU at about frame 40 port. This near-miss opened the side slightly and ruptured a sea chest for a magazine flood, eventually causing the flooding of five magazines and the handling room of one turret. It was necessary to dock the HONOLULU for repairs to the shell and to replace some electrical circuits which were flooded out. The Ship was ready to sail early in January.

(8) The HELENA was also moored at a Navy Yard pier. Her only damage resulted from the torpedo hit in way of machinery spaces on the starboard side. The HELENA was the first ship docked in No. 2 drydock at Pearl Harbor, which was not yet completed on December 7. Temporary repairs were made to the HELENA'S hull to make her seaworthy, after which she proceeded to Mare Island for permanent repairs and the installation of machinery and equipment which had been destroyed.

(9) The destroyer SHAW was an interesting case of repairing a severely damaged vessel. As a result of a bomb hit, the forward magazines of the SHAW blew up and wrecked all of the ship forward of the bridge. First appraisals were that the SHAW was a total wreck but in due time it was found that the machinery and the whole ship other than the forward area were in good condition. At the earliest opportunity the SHAW was removed from the wrecked floating drydock and redocked on the marine railway. There she was trimmed off neatly and measured up for a false bow, which was eventually fabricated and installed at a subsequent drydocking. About February 10 the SHAW set sail for Mare Island under her own power, the first "wrecked" vessel to do so. Her skipper and crew were a proud set of people, and that same feeling of satisfaction permeated all of Pearl Harbor as the SHAW successfully ran her trials and then departed for the mainland.

(10) The floating drydock YFD-2 was struck by 5 bombs, 4 of which affected very seriously her watertight integrity. As work on her proceeded it was ascertained that her watertight compartments were pierced by over 150 fragments. There was also considerable fire damage. Holes affecting water tightness were patched or plugged so that the drydock could be floated on January 9, 1942. Thereafter permanent repairs were proceeded with so that the drydock was again placed in limited use on January 26, 1942 and continued to serve a most useful purpose throughout the war.

--38--

RAISING AND SALVAGING OF THE NEVADA

When the Japanese attack began, the NEVADA, was moored in the berth next to the ARIZONA. In accordance with the Fleet doctrine she immediately prepared to get underway, and was able to do so although suffering from one torpedo hit. As she steamed down the channel toward the sea entrance she was heavily attacked by dive bombers and suffered 7 or 8 bomb hits. Two of these hits in the forward areas induced serious flooding. By the time the NEVADA reached the entrance she had taken on a great amount of water and it was apparent to the plucky young officer then in command that the ship should not enter the channel at the risk of blocking same. Accordingly, he decided to beach her and did a very successful job so doing. The fine spirit of her personnel which permitted the NEVADA to get underway and fight off her attackers soon was to carry her over the difficulties of refloating and rehabilitation and the eventual return home under the ship's own power.

As the NEVADA lay beached near the entrance channel to Pearl Harbor she really was a sorry sight to behold. It was not a pleasant spectacle for new ships arriving to reinforce or support the Pacific Fleet. Her stern was only a few feet from the shore, while her bow was practically submerged in the deep water near the channel. The forecastle was pretty much a tangled mess of twisted steel, and the superstructure up through the bridge had been entirely gutted by fire. The inside of the ship was completely filled with water and fuel oil.

There was considerable doubt in most minds as to whether the ship could ever be floated, and there were very few who even dimly hoped that she could be of any further military value. The "Cook's tour" of damaged ships by newly arrived personnel usually brought forth pessimistic forecasts regarding the NEVADA — and she was the least damaged of the battleships which had been sunk.

OPTIMISM -- However, the officers and men of the NEVADA, who had not been transferred were full of optimism, optimism that seemed a bit foolhardy perhaps. They insisted, especially the Engineer Officer, that the remainder of their crew be kept together in order that the ship when raised might be returned to the mainland under her own power. This fine spirit of the ship's personnel was greatly respected and appreciated. Their request was approved, but with some mental reservations. Yet this time optimism paid off!

--39--

FLOODING -- Immediately following December 7 the crew of the ship had set to work to remove wreckage and to condition the ship for salvage operations. Salvage personnel, including divers, had made a careful check of underwater damage and had found that most of the flooding occurred through three large holes — one a torpedo hit on the port side at frame 40 and 20 feet below the waterline, and two bomb hits, the first at frame 13 starboard which passed through the forecastle and out through the shell about 13 feet below the main deck. This bomb exploded alongside the ship and opened up a triangular hole about 25 feet long and 18 feet deep, which was responsible for most of the flooding of the ship. A second bomb passed through the bottom of the ship. It exploded in the water and left a hole about 6 feet in diameter. As a matter of special interest, this bomb passed through the large built-in gasoline tanks without igniting the contents,

USE OF PATCHES -- In order to shut off flooding from the torpedo hole a large wooden patch was manufactured by the Navy Yard. This patch was shipshape, about 55 feet long and 32 feet deep, and extended around the turn of the bilge. The shape of the patch was obtained from measurements taken from the exposed bilge of the OKLAHOMA which was a sister ship of the NEVADA. The patch was a massive affair and proved unsatisfactory for the purpose intended. The divers were unable to fit the patch to the hull of the ship satisfactorily for a number, of important reasons, one of which was that it just seemed too large to handle satisfactorily in one piece. Eventually it was decided to endeavor to unwater the NEVADA without this large patch, on the assumption that some of the bulkheads in area of the damage would be sufficiently intact to restrict the inflow of water, at least to a degree which would permit internal measures to be taken.

The two holes caused by bombs in the bow area were temporarily patched by wooden patches ordinarily referred to as window frames. The work was done by divers on the outside. The patches were drawn up reasonably tight by hook bolts. The bolts were hooked into holes burned into the small shell plating by underwater cutting torches.

All hull openings were plugged wherever possible by divers. Broken airports under water were made tight by use of wooden plates and draw bolts, Drain scuppers were plugged with mattresses, wooden plugs, and other similar material.

PUMPS USED FOR THE WORK — A large number of gasoline-driven suction pumps were used to unwater the NEVADA, varying in size from 3" to 10". Inasmuch as the maximum lift of a suction pump under the operating conditions embodied was about 15 feet, it was necessary to install pumps at various

--40--

levels throughout the ship. The small 3" pumps were used for "clean-up" jobs, such as for the final water in cut-up compartments, corners, etc. An excellent organization was developed to operate the pumps continuously, and this organization became very adept at diagnosing troubles and remedying them.

In the case of ships floated after the NEVADA a much improved pump became available. This was the "deep-well" pump which was of the centrifugal type operated by a propeller shaft extending from the topside to the bottom of the vertical piping. Of course such pumps could be used for straight pipe lines only, and were ideally suited for use in trunks such as were common on the battleships under salvage. These pumps came in sizes varying from 8" to 12" and were capable of handling tremendous quantities of water; the 10" pump would handle about 4000 gallons per minute.

REMOVAL OF WATER -- As indicated heretofore, the NEVADA was completely filled with sea water and oil. The plan for floating the ship contemplated, the installation of a sufficient number of pumps to remove the water faster than it could flow into the ruptured shell with patches in place to the extent mentioned. As the unwatering work commenced it was apparent that there would be no difficulty in floating the vessel. However, the amount of space from which water was removed at any one time had to be governed by a schedule taking into account a large number of considerations. Some of these pertained to stability and list of the ship; others had to do with making temporary repairs inside the vessel as the water was removed, such as stopping off leaks, shoring bulkheads, etc. Others pertained to removal of debris, cleaning, preservation of mechanical and electric equipment, etc.

EFFECTS OF TWO MONTHS' SUBMERGENCE — As the water level was reduced inside the ship it was noted that all surfaces were deeply coated with fuel oil. This had some good effects but mostly bad. Steps were taken to organize working parties to remove such coating by hosing down with a hot caustic solution and rinsing with salt water. Sand was placed on the decks to improve footing. As various compartments were uncovered the ship’s force removed the wreckage, stores, provisions, and eventually ammunition. Electric motors and certain items of auxiliary machinery were removed as soon as possible after they were unwatered. The motors were sent to the Navy Yard for reconditioning, as were also many pieces of equipment. As the work went on it was found that although the motors had been submerged in salt water for about two months

--41--

it was possible to recondition them for service in about 95 per cent of the cases. It was also found that items of mechanical machinery that had been protected by the fuel oil were 100 per cent salvable. Even delicate instruments such as electric meters were capable of reconditioning.

As the main machinery spaces were pumped out it began to seem very probable that the machinery could be put in operable condition, and all hands developed an accelerated optimistic spirit regarding the ability of the NEVADA to go home under her own power. The crew of the NEVADA (about one-third original crew) applied themselves most strenuously to the job of cleaning up the ship and especially toward getting the machinery and equipment in running condition.

As successive stages of pumping were undertaken the bow rose higher and higher in the water, and it soon became clear that no great difficulty would be found in floating the ship. However, it was important to reduce the draft as much as practicable, and for this reason it was decided to remove all the oil still remaining aboard and as much of the storeroom and magazine contents as practicable. The removal of oil was undertaken by operating the vessel's fuel oil transfer pumps on compressed air which was furnished by portable compressors. The operation was wholly successful and marked the beginning of self-operation on the part of the NEVADA.