AN ADMINISTRATIVE HISTORY

OF THE BUREAU OF SHIPS DURING WORLD WAR II

VOLUME III

U. S. BUREAU OF SHIPS

FIRST DRAFT NARRATIVE PREPARED BY THE HISTORICAL SECTION BUREAU OF SHIPS

TABLE OF CONTENTS

VOLUME III

|

CHAPTER |

PAGE |

||

|

PART IV |

|||

|

XIV. |

OFFENSIVE STRATEGY AND THE BUREAU |

1 |

|

|

The Strategy |

|||

|

The Balance of Fleets |

|||

|

The Impact upon the Bureau |

|||

|

XV. |

MAINTENANCE, CONVERSION AND REPAIR |

13 |

|

|

Introduction |

|||

|

Repair: |

|||

|

Continental |

|||

|

Advanced Base |

|||

|

Ship Repair Units |

|||

|

Conversion |

|||

|

Spare Parts |

|||

|

Background and Problems |

|||

|

Systems and Categories |

|||

|

Automatic Flow |

|||

|

XVI. INDUSTRIAL RELATIONS |

125 |

||

|

Bureau Organization for Industrial Relations |

|||

|

Manpower |

|||

|

Labor Relations |

|||

|

Conclusions for the Future |

|||

|

XVII. SHIPBUILDING AND HISTORY OF THE WAR |

149 |

||

|

The Strategy |

|||

|

Chronology |

|||

|

Reflecting Strategy: |

|||

|

Precedence Lists |

|||

|

Construction Directives |

|||

|

Production Board |

|||

|

Facilities and Their Expansion |

|||

|

Field Activities of the Bureau |

|||

--iii--

CHARTS

[Get chart page numbers from hardcopy or from

this text if I forget to add them.]

|

Chart No. |

Title. |

Page |

|

XIV |

Vessels and tonnage on hand, cumulative, July 1940 to January 1946 |

|

|

XV |

United States Naval Shipbuilding Program: |

1 |

|

XVI |

Graph of New Construction by tonnage and number of vessels of all types. |

1 |

|

XVII |

Expenditures by types of ships in World War II. |

2 |

--iv--

TABLES

|

Table No. |

Title |

Page |

|

49 |

Estimated strength of principal naval powers in major combat vessels as of January, 1944. |

7 |

|

50 |

Alteration, conversion, or fitting out work in continental

naval facilities |

18 |

|

51 |

Shipyard employees building and repairing U.S. Naval vessels, |

22 |

|

52 |

Shipyards repairing and converting, 1940-45. |

23 |

|

53 |

Advanced base components procured, 12-7-41 to 8-15-45 |

48-50 |

|

54 |

Vessels and tonnage converted, 1939-45. |

80 |

|

55 |

Major changes in precedence on naval vessels. |

179-181 |

|

56 |

New Construction and conversions directed |

185 |

|

57 |

Major combatant vessels of the U.S., Great Britain, |

193 |

|

58 |

New Construction by tonnage and number of vessels of all

types of Combatant

vessels |

195 |

|

59 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, mine craft |

196 |

|

60 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, patrol craft |

197 |

|

61 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, auxiliaries |

198 |

|

62 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, district craft (self-propelled) |

199 |

|

63 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, district craft (non-self-propelled) |

200 |

|

64 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, large landing craft |

201 |

|

65 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, small landing craft. |

202 |

|

66 |

New construction by tonnage and number of vessels, small boats |

203-204 |

--v--

TABLES Cont'd

|

Title |

Page |

|

|

67 |

Conversion of combatant, mine craft, and patrol |

205 |

|

68 |

Conversion and acquisition of auxiliaries, |

206 |

|

69 |

Conversion and acquisition of district craft (self-propelled) |

207 |

|

70 |

Conversion and acquisition of district craft (non-self-propelled) |

208 |

|

71 |

Acquisitions: small landing craft and small boats |

209 |

|

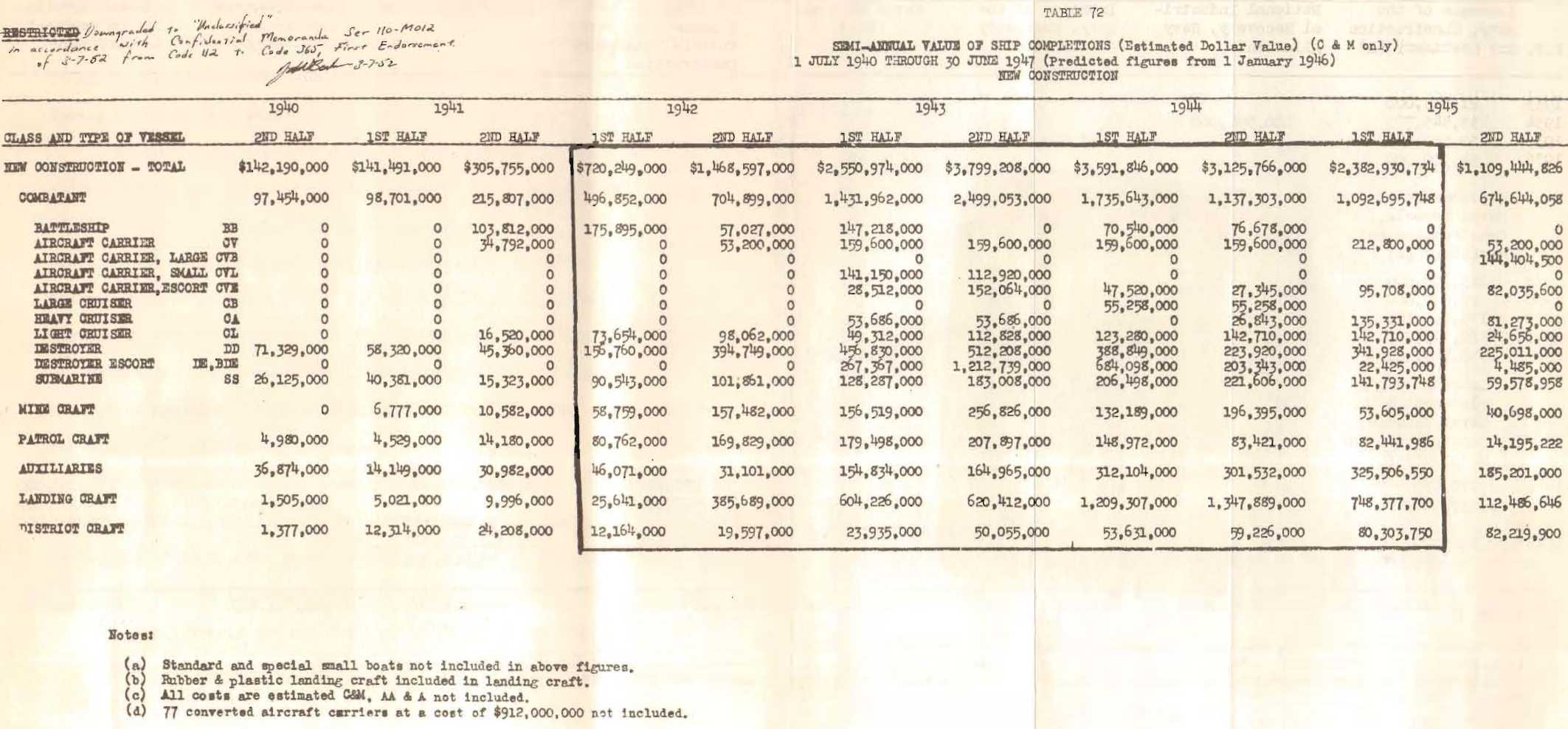

72 |

Semi-annual value of ship completions by type of ships. |

213 |

|

73 |

Appropriations for construction, acquisition, and Conversion of ships |

214 |

|

74 |

Field Activities administered by the Bureau of Ships |

218-220 |

--vi--

PART IV

THE OFFENSIVE PHASE OF WAR AND VICTORY AUGUST 1943 TO AUGUST 1945

The Last 24 Months

CHAPTER XIV

OFFENSIVE STRATEGY AND THE BUREAU OF SHIPS

CHAPTER XIV

OFFENSIVE STRATEGY AND THE BUREAU OF SHIPS

I. Strategy of the offensive phase.

The tide of the war had definitely turned by August 1943. Guadalcanal had been secured for six months; the New Georgia campaign was rapidly drawing to a close; the Aleutians had been secured; Africa had been conquered and Sicily invaded; the Axis submarines in the Atlantic were now a problem, rather than a menace. The Japanese strongholds of Truk and Rabaul were under constant attack. Our New Guinea forces had moved up the coast as far as Salamaua and our submarines were stabbing at the enemy's life line in the westernmost reaches of the Pacific. On all fronts the enemy was on the defensive, but at this moment he was retrenching in heavily fortified positions in the taking of which the allies would encounter considerable difficulty.

The significance of the Bureau of Ships' miraculous shipbuilding program in this shift in the fortunes of war has already been described. The offensive strategy, however, required an overwhelming superiority of ships, submarines, boats and landing craft, so that a heavy responsibility for operational success continued to devolve upon the Bureau of Ships and its activities.

Now, under the strategy of full-fledged offensive warfare in all theaters, the role of the Navy was to become widely dissimilar in the two major campaigns. In Europe the naval forces were to be concerned primarily with two "battles of the beaches" - in Italy and against the

--1--

PLANNING THE DOWNFALL OF THE JAPANESE EMPIRE: GENERAL DOUGLAS MACARTHUR, PRESIDENT F. D. ROOSEVELT, ADMIRAL WILLIAM LEAHY AND ADMIRAL CHESTER NIMITZ,

[PROOFERS, please see original for complete

caption.]

--2--

western shores of Europe - and following this, the major task was to be one of protecting the trans-Atlantic sea routes against the Axis submarines and of using these lanes for the transportation of troops and supplies. The magnitude and importance of the anti-submarine warfare are difficult to over-emphasize in the overall strategy and operation of the Atlantic war.

In the Pacific, however, warfare still involved, above all, "crossing the ocean". Important steps in the crossing were the Gilbert and Marshall Islands, which would serve as staging bases for further steps westward, as diversions of enemy troops from the northern Solomons and New Guinea campaign, and as training grounds for the new air and surface units of the Fleet. With these bases, the allied fleet might then attack by air and sea the intermediate zone of defense for the Japanese empire -Marianas, Carolines and Kuriles. Following the neutralization of New Guinea by the strategy of "coast hopping" the plan then called for the occupation of Palau and for the return to the Philippines. From this point the attack upon the homeland of the empire might better be prosecuted if circumstances so dictated. In the northern reaches of the Pacific, the Aleutians - the strategic aerial highway between the North American continent and the Far East - now fell under allied control and became an area of defense against any possible counter-attack. The submarine counted heavily in the planning for the offensive operation. As it is impossible to over-emphasize the submarine's importance during the dark early days of the war, so the extent of their vital role in the offensive area eludes description.

--3--

This strategy for the prosecution of global warfare, however, rested, to a considerable degree upon production. As Admiral King reported, "The best officers and men can do little without an adequate supply of the highly specialized machinery of warfare." He continued, saying that "Our guiding policy is to achieve not mere adequacy but overwhelming superiority of material." The responsibility for producing this "overwhelming superiority of material" for naval warfare rested to a large degree upon the Bureau of Ships and its associated activities. However remarkable the production program may have been during the defensive and pivotal phases of the war, the greatest production program under the Bureau was yet to come.

II. BALANCE OF FLEET.

The successful operations by the allied armed forces and the unbelievable shipbuilding production of the United States placed the allied nations in a most favorable position with regard to naval strength as the offensive phase of the war began in mid 1943.

According to the overall strategy, Great Britain's navy was to provide considerable assistance to the American fleet during the invasion of the European continent. Following that, however, its task would be, primarily, the maintenance of a "fleet in being" to keep the German fleet "bottled up." The other allied and axis fleets played minor roles in the European scheme of things. Therefore, only a portion of our naval strength was deployed in the Pacific to grapple with the Japanese. The comparative strength of these two nations may be found on the following table 49 which lists the major combatant vessels of the principal naval powers as of January 1944.

--4--

U.S.S. PHILIPPINE

SEA CV-47

ANOTHER CARRIER ENTERS THE WATER TO ADD TO U.S. NAVY'S

"FLAT TOP" STRENGTH

--5--

Only in heavy cruisers did the Japanese approach the American navy in strength at this time. In all other classes the Japanese proved woefully inferior, but they were favored with the advantages of fighting a defensive war and of having shorter lines of communication and supply.

In contrast, the allied forces still had the ocean to cross. In battleships, aircraft carriers, light cruisers and submarines, the America fleet enjoyed a strength double that of the Japanese; in carrier escorts, destroyers and destroyer escorts, the Japanese suffered an overwhelming inferiority.

In addition to this favorable growth of combat vessels, one of the most important factors in the successful execution of the strategic plans was the adequate production of landing craft and of large assault transport These two programs, as the tide turned, assumed highest priority. In view of the offensive nature of these vessels and the defensive position of the Japanese after this time, comparison of these vessels in the two navies would prove of little significance. In truth, the Nipponese suffered so badly by the contrast in these classes that a comparison could scarcely be drawn.

III. IMPACT UPON THE BUREAU.

A. Organization:

Immediately following the inception of the Allied offensive phase in mid-1943, no major Bureau of Ships' reorganizations were effected. Several minor alterations occurred, however, to strengthen the organization structure.

--6--

ESTIMATED COMPARATIVE NAVAL STRENGTH OF PRINCIPAL NAVAL POWERS IN MAJOR COMBAT VESSELS AS OF JANUARY 1944 SOON AFTER THE INCEPTION OF THE ALLIED OFFENSIVE PHASE

|

TYPE |

BRITISH EMP. |

FRANCE |

RUSSIA |

UNITED STATES |

JAPAN |

ITALY |

GERMANY |

|||||||

|

No. |

Tons. |

No. |

Tons. |

No. |

Tons. |

No. |

Tons. |

No. |

Tons. |

No. |

Tons. |

No. |

Tons. |

|

|

Battleships |

15 |

481,170 |

5 |

136,567 |

4 |

98,150 |

22 |

731,700 |

10 |

345,020 |

6 |

177,944 |

4 |

101,600 |

|

Aircraft Carriers |

6 |

137,450 |

1 |

22,146 |

--- |

----- |

19 |

356,000 |

9 |

199,070 |

-- |

------ |

--- |

----- |

|

Carrier Escorts |

37 |

377,029 |

-- |

----- |

--- |

---- |

35 |

299,668 |

6 |

84,000 |

-- |

------ |

--- |

----- |

|

Heavy Cruisers |

12 |

118,945 |

3 |

30,000 |

7 |

59,600 |

16 |

168,675 |

15 |

175,100 |

2 |

20,000 |

4(b) |

51,400 |

|

Light Cruisers |

52 |

331,819 |

8 |

57,280 |

1 |

7,000 |

32 |

271,775 |

17 |

84,665 |

9 |

51,975 |

4 |

23,400 |

|

Destroyers |

220 |

306,487 |

21 |

28,610 |

52 |

96,200 |

328 |

570,850 |

83 |

123,787 |

23 |

36,855 |

38 |

64,125 |

|

Escort Destroyers |

60 |

62,130 |

-- |

------ |

-- |

----- |

-- |

----- |

-- |

— |

----- |

-- |

---- |

|

|

Destroyer Escorts |

136 |

179,525 |

2 |

2,640 |

31 |

20,870 |

251 |

318,050 |

18 |

21,600 |

41 |

28,507 |

33 |

18,680 |

|

Submarines |

105 |

82,902 |

20 |

16,890 |

165 |

110,000 |

172 |

219,830 |

87 |

127.840 |

51 |

42,995 |

320(a) |

186,958 |

|

TOTAL |

643 |

2,077,457 |

60 |

294,133 |

391,820 |

2,936,548 |

245 |

1,161,082 |

132 |

358,276 |

403 |

446,163 |

||

|

TOTAL ESTIMATED FORCES |

ALLIED POWERS |

AXIS POWERS-- |

||

|

No. |

Tons. |

No. |

Tons. |

|

|

Battleships |

46 |

1,447,587 |

20 |

522,964 |

|

Aircraft Carriers |

26 |

515,596 |

9 |

199,070 |

|

Carrier Escorts |

72 |

676,697 |

6 |

84,000 |

|

Heavy Cruisers |

38 |

377,388 |

21 |

246,500 |

|

Light Cruisers |

93 |

667,874 |

30 |

160,040 |

|

Destroyers |

621 |

1,867,947 |

144 |

224,767 |

|

Destroyer Escorts |

420 |

521,085 |

92 |

68,787 |

|

Escort Destroyers |

60 |

62,130 |

— |

— |

|

Submarines |

462 |

429,622 |

458 |

357,793 |

|

TOTAL |

1838 |

5,699,958 |

780 |

1,965,521 |

--7--

In the summer of 1943, two Bureau of Ships' activities --- the Advance Base Sub-Section of the Shipbuilding Division and the Base Maintenance Branch of the Maintenance Division --- were consolidated for administrative purposes.

Another change designed to clarify Bureau operations was made on 29 October 1943, when all facilities sections were made responsible to a single head and this officer in turn was given duty as Joint Staff Assistant to the Head of the Maintenance Division and Head of the Shipbuilding Division. This change transferred the facilities codes from the Contract Branch of the Shipbuilding Division to the Joint Staff Assistant. On 30 December 1943, final action was taken establishing a Facilities Branch of the Shipbuilding Division.

The year 1944 occasioned considerable alteration of the Bureau's organizational structure. This came to pass to a marked degree by the readjustment following the extremely concentrated efforts of the entire Bureau during the first half year upon the landing craft program for the invasion of Normandy and for the accelerated pace of the Pacific operations Following this period of unprecedented output, the workload tended to fall off and reorganizations ensued.

Two moves taken in June 1944 reflected the changed emphasis already felt or anticipated in the Bureau's workload. On 10 June 1944, a Contract Termination Section was established in the Contract Branch of the Shipbuilding Division and on 19 June a Contract Division was established, centralizing all contract negotiation and administration except for radio, radar and sonar, and including a Cost and Labor Estimates Section. On 15 July the exception made for electronics equipment in the establishment

--8--

of the original Contract Division was rescinded and final authority for all contracts was placed in the Contract Division.

These new trends also led to another minor revision on 21 October 1944, when the Contract Termination Branch was established in the Contract Division. This Branch was responsible for all terminations except for facilities contracts, which remained with the Facilities Branch of the Shipbuilding Division.

During the first part of the year 1944, considerable attention and thought were devoted to the major problem of spare parts and maintenance of the vastly expanded fleet. Although this topic is discussed at great length in the following chapter (XV), it is necessary here to point out the organizational changes which the Bureau effected to handle this new paramount problem.

On 3 February 1944 a Spare Parts Section was established in the Shipbuilding Division. Later, in August 1944, a Materials Branch became established to operate jointly under the Maintenance and Shipbuilding Divisions, with an eye to spare parts control, inventory control, and scheduling of spares. Its task was that of coordinating procurement of all materials and components for new construction and maintenance and coordinating the activities of the Scheduling and Statistics Section devoted to CMP and requirements determination. In his report to the Secretary of the Navy in March 1945, Fleet Admiral Xing mentioned another problem of considerable importance to the Bureau of Ships. He stated: Because the postwar size of the Navy is yet to be determined no precise estimate of the number of naval personnel (or of ships) that will be

--9--

required, is possible. The deciding factor (of both) will be the needs of the Navy in order to carry out the strategic commitments of the nation. However, for more than a year we have worked on demobilization methods and have completed tentative plans." Within the Bureau these methods and plans fell under the cognizance of the newly established (April 1944) Demobilization Section of the Maintenance Division. This forward looking action is discussed in its overall aspects in Chapter XXIV --- "The Reserve Fleet". The matter of primary importance is the foresight of the Navy Department and the Bureau of Ships in placing emphasis upon a post-war problem during the height of the war.

Some purely incidental changes occurred on 15 December 1944. The Radio Division became the Electronics Division, the Maintenance Division became the Ship Maintenance Division, and the Heads of the Divisions were designated as Directors.

Two changes in the year 1945 stand out and represent a major shift in Bureau administration. The first was the consolidation of the Shipbuilding and Maintenance Divisions in almost all operating relationships. The second was the establishment of a Shore Division.

From the inception of the Bureau, maintenance and new construction had been separated, parallel ship type desks being maintained throughout. As the pressure for the new construction program declined and the maintenance load increased, it was generally accepted that more effective results could be obtained and more efficient utilization of personnel would result if the type desks were consolidated. A gradual program

--10--

U. S. S. FRANKLIN - CV13 HOMEWARD BOUND

--11--

was undertaken, therefore, on 28 March 1945 to consolidate all construction and maintenance type desks. The first step taken on that date involved the carrier desks of the two Divisions. As of 4 April 1945, the Construction Branch of the Shipbuilding Division and the Ship Maintenance Branch of the Maintenance Division were consolidated to form a Ship Technical Branch under the joint direction of the Directors of Shipbuilding and Ship Maintenance. From this date on, action was taken to reorganize the parallel ship type desks as rapidly as possible. Although the new organization permitted the more efficient discharge of the Bureau's responsibilities, no marked reduction in personnel was possible, due to the magnitude of the repair and maintenance job.

The second major change -- the establishment of the Shore Division on 20 April 1945 --- charged this new division with responsibility for the "efficient management and operation of those industrial production activities of the naval shore establishment for which the Bureau of Ships is responsible." This included all equipping of Navy Yards, private shipyards and manufacturing plants under Bureau of Ships sponsorship; operation of seized plants; maintenance or disposition of facilities no longer required for active production, etc. The Facilities Branch and Labor Relations and Manpower Section of the old Shipbuilding Division and the Base Maintenance Branch of the old Maintenance Division formed the core of the new Shore Division.

In this fashion, therefore, did the Bureau of Ships adjust itself to changing tides of the war as the Allied forces advanced and expanded under their offensive strategy. The following chapters of this section will show the Bureau's vital role in this offensive.

--12--

CHAPTER XV

MAINTENANCE, CONVERSION AND REPAIR

CHAPTER XV

MAINTENANCE, REPAIR, AND CONVERSION

A. Introduction

One of the prime responsibilities of the Bureau of Ships is to provide for the maintenance, repair and salvage of all naval vessels. In addition, the Maintenance Division of the Bureau as originally constituted was made responsible for the conversion of vessels held by private interests to meet the needs of the fleet.

The Bureau's interest in maintenance, repair and salvage work grew from relatively small proportions prior to the war until they were the most critical of all Bureau activities in the summer of 1945. The primary reason for this change was the success of the new construction program, which so increased the size of the fleet that by mid 1945 over 13 million tons of vessels of all types had to be serviced, whereas at the outset only slightly over 2 million tons were in service. Chart XIV presents vividly the nature of this expansion.

--13--

Three other factors increased the maintenance load of the Bureau: First, it was rapidly found that war conditions greatly increased the work load. Vessels steamed faster, further and under more adverse conditions than in peacetime. Crews were so green and experienced officers spread so thinly that many breakdowns of equipment occurred which might have been avoided in normal times. Second and most obvious were the salvage and repairs made necessary by battle damage. Pearl Harbor and the Kamikaze attacks of late 1944 and early 1945 resulted in the most conspicuous battle damage Jobs, but throughout the war many vessels were repaired and sent back to Join the fleet after the Japs had been reasonably confident that they would never see action again. Third was the problem of procuring and distributing necessary spare parts and material to the areas needed. As the theater of operations expanded this tended to tie up more and more material in pipe lines and inventories, greatly increasing the burden on the Bureau.

The maintenance and repair duties of the Bureau included frequent overhauls of all types of vessels and extensive changes in the armament and other installations of vessels to incorporate improvements gained by experience as the war progressed. The complete rebuilding of some obsolete vessels was undertaken, but most additions and modifications were less extensive. Throughout the

--15--

war equipment and guns were added to improve the defensive characteristics of surface craft against aircraft attack. Increases in communications facilities were found necessary and, with the advent of radar, a complete overhauling of fire control and aircraft detection devices was undertaken, leading to the development of the combat information center, which required many changes in the internal arrangements of ships. Other major changes included the addition of much fire fighting equipment and the elimination of all combustibles, including in older vessels layers of paint which were found to be particularly dangerous in the event of any widespread fire; improvements in methods of gasoline stowage, extensive additions to the splinter protection provided for exposed personnel and, finally, for ships engaged in amphibious work the addition of boat handling facilities and provision for boat stowage, primary requisites for their participation in amphibious attack.

The actual responsibilities of the Bureau may be divided into two major parts: Repairs in continental Navy establishments and other major bases, such as Navy Yard, Pearl Harbor on the one hand, and advanced base repairs on the other. The Bureau's interest in the continental establishments carried through to the actual supervision and scheduling of the work in the Yard. The Bureau's interest in advanced base repair was confined to the provision of equipment and material necessary for the advanced base to perform its function. The Bureau did not maintain any direct control over the manner in which the work was done in advanced bases.

--16--

Although salvage and foreign ship repair have already been discussed in Chapter XII under the defensive phase of the war, it must be kept in mind that throughout the latter half of the hostilities these activities played an active, although relatively minor, part in the over-all war program. This chapter will concern itself with three activities of major importance in the prosecution of the war: repair, conversion and maintenance. The failure of any one of these phases would have occasioned most serious repercussions in the global picture as one of them, maintenance, almost proved.

--17--

B. REPAIR:

1. Repair, Continental Naval Facilities and Pearl Harbor

Repair of Naval vessels in peace has always been concentrated in Navy Yards or other Naval facilities. During the war same exceptions were made to this rule, particularly on the West coast, but almost all major repair jobs were done in Naval facilities. Table 50 below indicates the growth of repair work for the fiscal year 1939 through fiscal year 1945.

TABLE 50

Alteration, Conversion or Fitting out Work in Continental Naval Facilities and Navy Yard Pearl Harbor

|

Number of Vessels Available |

|||||||

|

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

Fiscal |

|

|

Combatant |

230 |

209 |

389 |

844 |

1,591 |

3,873 |

3,840 |

|

Auxiliary |

60 |

51 |

169 |

426 |

970 |

1,495 |

2,925 |

|

Minecraft |

17 |

21 |

51 |

279 |

655 |

1,878 |

2,603 |

|

Patrol Craft |

- |

- |

31 |

163 |

1,116 |

2,774 |

3,435 |

|

landing Craft |

0 |

0 |

0 |

0 |

483 |

1,754 |

4,834 |

|

District Craft |

- |

- |

7 |

134 |

782 |

1,187 |

1,891 |

|

307 |

281 |

647 |

1,848 |

5,597 |

12,961 |

19,528 |

|

Data on all availabilities prior to fiscal year 1941 are relatively incomplete and data on District Craft are believed to be incomplete for the entire period covered.

--18--

Under the conditions which existed throughout the war, vessels were not made available unless they were either so badly in need of repair they could not continue to operate with the fleet or were in need of such extensive alterations that they would otherwise be considered obsolete. Work done on vessels was not undertaken lightly but as a result of considered Judgment that the vessel in question had to be repaired, converted or whatever to maximize the fighting strength of the fleet. There is no measure of the actual work load that would permit comparisons between repair and new construction, for repairs and alterations could range from the addition of relatively minor pieces of equipment or repair of such equipment to the practical reconstruction of the vessel. In the case of some of the badly damaged ships complete new bows, stems, or other sections of a ship had to be fabricated and Joined to the existing hull. Although battle damage reports were submitted to the Bureau and to the activity to do the repair work within a very short period after the vessel had suffered damage, the exact nature of the necessary repair work could not be finally determined until the vessel had been placed in drydock or tied to the pier in the Navy Yard. Advance planning was encouraged and in many cases complete sub-assemblies were ordered well in advance of the availability of the vessel on which they were to be placed, so that there was little delay between the time the vessel arrived at the yard and the Job was finished.

Advance planning could not, however, anticipate battle damage work loads before the damages occurred, so all Naval activities engaged

--19--

in ship repair had fluctuating work loads. For this reason an effort was always made to maintain some new construction which could be used to fill the gaps between major repair Jobs. Complete transferability of personnel or equipment, however, was not always possible, which occasioned a consequent loss of efficiency. In repair work, a much higher degree of skill is required to do the sort of improvisation required in patching up a badly damaged ship. For example, a very ordinary electrician can wire a new vessel under construction, but the same man might be unable to find out what needed to be reinstalled in the electrical system of a vessel which had been damaged. Similar differences in the skills required were found in other key trades.

The greatest problem in the field of labor grew out of the fact that in the latter stages of the war the heaviest repair loads were found on the West coast, which had the tightest labor market in the country. Grave difficulties were experienced in even maintaining the unskilled labor necessary to man the existing facilities.

The two new Naval facilities on the coast, built primarily to repair major fleet units, Terminal Island and Hunter's Point, were never able to recruit sufficient manpower to meet all their needs. Similar, although less acute, problems were faced by all other Naval establishments.

The overall manpower shortage in shipyards building or repairing ships became a matter of paramount importance after the tide of the war had changed in 1943. Table 51 lists the number of shipyard employees

--20--

concerned with the building or repairing of U.S. naval vessels. When compared with Chart XIV (cumulative vessels and tonnage on hand) and Table 52 listing the number of shipyards repairing and converting, it is easy to imagine the magnitude of the problem: as the volume of repair and conversion increased and new construction slackened slightly, the fall in shipyard employment became critical.

--21--

TABLE 51

SHIPYARD EMPLOYEES

Building and Repairing

U. S. NAVAL VESSELS

|

January 1942 |

443,500 |

|

January 1943 |

911,900 |

|

July 1943 |

1,049,981 |

|

January 1944 |

970,900 |

|

January 1945 |

861,300 |

|

October 1945 |

572,800 |

--22--

TABLE 52

SHIPYARDS

REPAIRING AND CONVERTING

1940-1945

|

July |

1940 |

19 |

|

December |

1941 |

76 |

|

December |

1942 |

143 |

|

September |

1943 |

222 |

|

September |

1944 |

248 |

|

November |

1944 |

230 |

|

January |

1945 |

231 |

|

April |

1945 |

229 |

|

July |

1945 |

227 |

|

October |

1945 |

227 |

--23--

Each of the Navy Yards and shipyards within the continental limits of the United States had a distinct function to perform throughout the war, with special emergency tasks also being assigned as expediency directed. The Navy Yards’ general jobs and their location were:

|

Boston Navy Yard, Boston, Mass. |

Design and construction of destroyers, manufacturing of

chain, rope, etc., |

|

Portsmouth Navy Yard, Portsmouth, N. H. |

Design., construction and repair of submarines and

miscellaneous small ships, |

|

New York Navy Yard, Brooklyn, N. Y. |

Design, construction of heavy combatant ships, |

|

Philadelphia Navy Yard, Philadelphia, Pa. |

Design, construction of heavy combatant ships, repair

of miscellaneous types |

|

Norfolk Navy Yard, Portsmouth, Va. |

Design and construction of heavy combatant ships,

repair of miscellaneous types |

|

Charleston Navy Yard, Charleston, S. C. |

Minimum construction, one destroyer or similar size every

two years, |

--24--

|

Terminal Island Navy Yard., San Pedro, California |

Repair of surface ships of all sizes and minor manufacturing as assigned. |

|

Mare Island Navy Yard, San Francisco, California |

Minimum construction, one submarine every two years, |

|

San Francisco Navy Yard, San Francisco, California |

Repair of surface ships of all sizes, minor manufacturing as assigned |

|

Puget Sound Navy Yard, Bremerton, Wash. |

Minimum construction, one destroyer or similar craft

every one to two years, |

--25--

F644C7460

NAVY YARD, NEW YORK

AUGUST 19, 1944

SHOWING STBD. SIDE & STERN OF U.S.S. DE 401 AS AFT. SECTION IS BEING TRANSFERRED FROM U.S.S. DE 401 TO U.S.S. DE 320 IN D. D. #6.

CROSS SECTION OF U.S.S. DE 401 AT FRAME 119 IS ALSO SHOWN. STACK HAS BEEN REMOVED FROM HOLDER.

--26--

To illustrate better the function and purposes of these Navy Yards, a description of one of them—The Norfolk Navy Yard is quoted from that activity's handbook of information printed for civilian employees.

"A great variety or activities is carried on here in the Norfolk Navy Yard. But the Yard has only one purpose, that is to serve and strengthen the fleet. It does that through new construction, conversion, outfitting, repairs, alterations, and alterations-equivalent-to-repairs. Anything else is incidental to this main purpose.

"This is primarily a repair rather than a new construction yard. The word "repairs" is defined as the work necessary to restore the ship or article to serviceable condition without any change in design. "Alterations" may involve changes in design, additions of articles or parts, or changes in material of which an article or part is made.

"Alterations are frequently approved by "Shipalt", "Ordalt", or by other Bureau directive for an entire class or group of ships. The alterations will then be made at the first opportunity. A great deal of repair and maintenance work and even some alterations may be done by the ship's force while at sea. What cannot be done by the ship's force while at sea is noted by ship's officers so

--27--

that when it is time for them to put in to a navy yard they have up-to-date lists of alterations and repairs to he made. Those lists serve as a basis for the work request lists presented to the yard, the items falling into ten general groups, namely Repairs under each of the five following: Hull, Machinery, Electrical, Ordnance, and Electronics, and also Alterations under each of those headings.

"Before arrival, the ammunition, fuel or diesel oil, or gasoline, that would interfere with the work to he done should have been removed at appropriate depots or bases, and if time permits, fuel tanks steamed out and gasoline tanks flushed with salt water and filled with inert gas.

"Pre-Arrival Planning. Prior to arrival the Assistant Planning Officers of the group supervising her type assemble all information in the files regarding work to be investigated and • undertaken, noting particularly the status of authorized alterations, uncompleted job orders, and of plans and material procurement. A list of the outstanding jobs which are to be accomplished, either wholly or in part, during the vessel’s stay, is sent to the Production Officer so that work may begin as soon as the vessel arrives.

"Before arrival also the Ship Superintendent is appointed. He will meet the ship and see that power, steam, air and telephone lines are connected. He will introduce himself to the commanding and division officers.

The Arrival Conference

"An arrival conference is held, attended by the Ship Superintendent, Assistant Planning Officers and other yard representatives and representatives of the ship.

These officers keep in mind the Availability or length of time the ship is to he in the yard and decide what work the yard will do. Each item proposed is examined and carefully analyzed to determine its scope, need and, in the case of alterations, the authority for accomplishment.

Assistant Planning Officers are responsible for getting out the original Job Orders (J. O.) and the subsequent or amplifying instructions in Supplementary Work Orders (S. W. O.). The Ship Superintendent represents the Production Officer and his principal assistants in coordinating and accomplishing the work authorized on the vessel and is thus the Yard's representative immediately on hand at the work.

"Ship's force provides fire watch, guards, does miscellaneous cleaning, scraping, testing, and much of the painting; and if the ship is in drydock, will scrape the bottom.

"Briefly then the shops of the Industrial Department do the work of new construction, conversion, alteration or repair. The Supply Department gets the needed materials here. The Accounting Department pays the civilian employees and keeps accounts of costs and charges to be made against each authorization or allotment of funds under which the work is done. The Medical Department is concerned with the health of employees and naval personnel. The Disbursing Department pays the naval personnel. The Captain of the Yard (Military Department) looks after security of the Yard and exercises certain control over uniformed personnel while here. The Commandant has general over all control and is the highest authority in the Yard."

--29--

Advanced Base Repair

Although the Bureau of Ships is charged with the responsibility of providing for the maintenance of vessels and equipment under its cognizance, the bureau's administrative responsibility for the facilities necessary for this type of work does not extend beyond the continental limits and established bases in such places as Hawaii and the Philippines. In peacetime, ship repairs were accomplished by two distinct general methods: the shore or Navy Yard method, and the afloat or tender method.

From the outset of World War II, Navy Yards and other established ship repair facilities were soon flooded with new construction and major overhauls. Tenders capable of accommodating only minor overhauls or repairs and alterations could not meet the increasing demands of the fleet in advanced areas. It became necessary, therefore, to establish supply, repair and other service facilities in newly acquired advanced areas in order to eliminate as often as possible long return voyages to major repair facilities.

These repair and service facilities, known as "Advanced Bases", were established by direction of the Chief of Naval Operations and were administered by the operating Command in their respective areas. For the maintenance and support of

--30--

these bases it

was necessary to procure large quantities of equipment for shipment as directed

by the Chief of Naval Operations.

In 1942 it was

evident that the repair capacities of the initial advanced bases were

inadequate and that the apparent shortage of equipment reflected the necessity

for extensive revised planning. In the last quarter of 1942, therefore, a

system was evolved whereby self-contained units were designed to supply the

various types of services needed in advanced areas. These units were titled

"Advanced Base Functional Components" and incorporated the plans and

suggestions of both the forces afloat and the material bureaus. A particular

bureau was set up as the dominant bureau for each component. This bureau

furnished the major portion of materials, and also became responsible for the

coordinated assembly of the material contributions of other bureaus.

Components, when

assembled, were designed to perform a specific type of function such as repair,

medical, supply, administration, or harbor defense, etc. Upon arrival in an

advanced area, the combining of a group of components activated the

establishment of an advanced base, the mission of the base determining the

number and variety of components provided. The major assembly groups were

called: LION, CUB, ACORN GROPAC,

--31--

STANDARD PT BASE UNIT, STANDARD LANDING CRAFT UNIT, FLEET SUPPLY UNIT, AVIATION SUPPLY UNIT, HARBOR DEFENSE UNIT, STANDARD AIRCRAFT and ENGINE OVERHAUL UNIT.

The LION, the largest advanced base unit, provided personnel and material necessary for the establishment of a major all-purpose naval base. It consisted of a large number of functional components which enabled a base to perform voyage repairs and minor battle damage repairs to a major portion of the fleet, to provide logistic support for operating forces in the area, and to operate a large and active port. For its own support, it contained adequate harbor defense, communication, supply, disbursing, medical, ordnance and base maintenance facilities. The installation of a LION Unit required the services of construction battalions to assist in the unloading operation and to construct the base facilities.

The CUB provided personnel and material necessary for the establishment of a medium sized advanced fuel and supply base. It did not contain ship repair facilities. It was made up of a number of functional components which enabled it to provide logistic support for a small task group of light forces and to operate an active port. The installation of a CUB Unit required the services of construction battalions.

--32--

An ACORN was an advanced base unit consisting of personnel and material necessary for the establishment of an advanced air base. It contained plane repair facilities. It was made up of a number of functional components and, when augmented by a Carrier Aircraft Service Unit or a Patrol Service Unit, could service, rearm, and perform minor repairs and maintain the planes of one carrier group, one patrol plane squadron, or equivalent.

A GROPAC was a commissioned naval organization designed to install and operate harbor and waterfront facilities, and to provide certain harbor defenses for an advanced base. It normally provided for the unloading of ships; Installation and maintenance of navigational aids, piers, moorings, net defenses and underwater sound detection; the repair of small craft and harbor equipment; the operation of a harbor defense patrol; and the provision of a boat pool for use within the harbor. It provided, also, for its own administrative, communication, medical and housing needs. GROPACS varied materially from each other in size and composition since each was individually designed to meet the needs of a particular island or area.

A STANDARD PT BASE UNIT was designed for the maintenance of one squadron of PT Boats. This unit did not contain major engine overhaul facilities, and if they were desired an E12 component was added to the unit.

--33--

The function of a STANDARD LANDING CRAFT UNIT was to establish garrison boat pools in seized areas during the amphibious phase of assault operations in order to provide for shore-to-shore movements, harbor needs for personnel transportation, and for unloading of ships of the garrison echelons. The SLCU (Large) provided for two-shift operation - 24 hour continuous duty - of 50 LCM, 48 LCVP and 2 LCP(L). These craft were provided from amphibious assault shipping prior to final retirement from the objective area.

Concerning equipment COMINCH ordered:

(1) Equipment and supplies, exclusive of fuels and oils, to be loaded in the assault echelon were limited to one-half (1/2) ton per man and were to include a 30 days' supply of spare parts and 30 days' rations.

(2) The 30 days' supply of spare parts was to be boxed in four equal parts so that each might readily be loaded, together with 1/4 of the E10 personnel, in LSDs or ARLs which accompanied the assault echelons.

(3) The remaining equipment and supplies, which were to be kept to a minimum, were to be loaded in an early garrison echelon, to be in the custody of a small group of SLCU personnel.

The FLEET SUPPLY UNIT was an advanced base unit for the establishment of a complete supply facility. This unit contained a D1 component as a nucleus and possessed only those additional components which contributed directly toward the supply operation. No "A" or administration

--34--

U.S.S. PITTSBURGH

CA-72

Floating drydock outside of Agat Harbor in Guam. Bow was lost in typhoon June

1945.

--35--

component was assigned, as these functions could have been performed by the Dl. It is to be emphasized that the FLEET SUPPLY UNIT not only provided storage buildings, personnel and equipment, but also the stores or supplies to fill those buildings. Adequate space was provided to store enough base consumables to maintain a LION-type base, and, in addition, to store the following:

(a) Fresh provisions, 60,000 men for 30 days

(b) Dry provisions, 60,000 men for 90 days

(c) Clothing and Small Stores, 60,000 men for 90 days

(d) Ship's Stores, 60,000 men for 90 days

(e) Fleet supplies (GSK) equivalent to 10 BBB (basic Boxed Base) loads.

The Bureau of Ships served as the dominant bureau responsible for the procurement of ship and boat repair components or the so-called "E" components, and as the dominant bureau for most of the harbor control and defense components involving communications equipment, underwater sound protection, small boat pools, and harbor patrol.

The bureau also dominated the majority of communications components involving radio, radar and visual signalling components. Its final interest included waterfront and seadrome fire protection components. In addition to the cognizance of its components, the bureau also made extensive contributions to components under the dominance of other bureaus, amounting to approximately one third of the dollar value of the Bureau of Ships dominated components. Included

--36--

in this category were components for administration, supplies, aviation, ordnance, camps, and the miscellaneous functions. A detailed description of all major equipment, machine tools, and miscellaneous materials supplied in the various components has been summarized and published in the Advanced Base Initial Outfitting List - Abridged Catalogue.

The E-1 SHIP REPAIR (GENERAL) component, the largest under the domination of the Bureau of Ships, was designed to make voyage repairs and minor battle damage repairs to all types of vessels in the fleet. It was shore based, with shop facilities larger than a repair ship (AR) plus the special tools found on a destroyer tender (AD) and a submarine tender (AS). For its operation it required approximately thirty officers and 1300 enlisted men for a two-shift operation. The approximate weight of the E-1 was 3700 long tons and its cube was approximately 7500 measurement tons. Major repair facilities provided were as follows:

[Boiler and Shipfitter Shop Welding Shop

Blacksmith Shop and Foundry

Sheet Metal Shop

Coppersmith and Pipe Shop

Machine Shop (General)

Internal Combustion Engine Shop

Carpenter and Patternmaker Shop

Electrical and Refrigeration Shop

Battery Shop

Canvas and Gas Mask Shop

Radio, Radar and Sonar Shop

Gyro Compass Shop

Shop Consumables - 90 day initial supply (90 day

replenishment on request)

--37--

Housing - Approximately 13

utility bldgs. 40 x 100; 6 utility bldgs., 102 x 100; and one hanger type bldg. 200 x 200.

Waterfront Structures - Pontoon wharf, bridge, barges and propelling units

Transportation Equipment - Trucks, dock mules, dock trailers

and shop platform trailers

Construction Materials - Cranes, hoists, air compressors,

lumber, cement, hardware, etc.

Although the E1 component contained large and numerous repair facilities, the need did not arise to establish a large number of such facilities. As the war continued, stress was placed upon highly specialized components designed to perform a specific function. This was particularly true of equipment designed to repair and salvage various types of landing craft and assault vessels so that landing craft could be repaired in time to carry succeeding waves of the initial assault. A description of the major repair and specific types of components follows:

E2 - SHIP REPAIR (CAPITAL SHIPS)

Made voyage repairs and repaired minor battle damage to all types of vessels in the fleet, primarily to capital ships. It was the shore based equivalent of the shop facilities of a repair ship (AR), minus all ordnance shops.

E3 - SHIP REPAIR (DESTROYERS)

Made voyage repairs and repaired minor battle damage to most types of ships, but particularly to destroyers or smaller vessels. It was the shore based equivalent of a destroyer tender (AD), minus ordnance shops.

--38--

E5 - SHIP SERVICING COMPONENT

A docking and working party intended to perform ship's force work such as running out fuel and power lines, assisting in docking, moorings, provisioning and other such service functions.

E6 - LANDING CRAFT AND EASE REPAIR COMPONENT

Repaired both hulls and engines of all types of landing craft. It was specifically designed to maintain the following craft for six months:

|

12 LST |

36 LCT (5) or LCT (6) |

|

|

12 LCS(L) (3) |

200 LCMs |

|

|

12 LCI(L) |

100 LCV(P)s |

|

|

12 LSM |

||

E6A - LANDING CRAFT SPARE PARTS (LARGE)

This component was designed to be added to an E6 component. It provided initial stocks (six months' supply) of hull, machinery and internal combustion engine spare parts for landing craft.

E8 - REPAIR - SMALL BOAT

Maintained and repaired both hulls and engines of the small boats at a small or medium sized advanced base having 25 assorted craft Including 50' tank lighters and 36' landing craft.

E9 - REPAIR - SMALL AMPHIBIOUS CRAFT (MOTORIZED)

A truck mounted component designed to make hull and engine repairs to 50' and 36' amphibious craft and other small boats at any point beyond the range of stationary repair facilities. Basically it had three distinct functions:

(1) It could be moved from its parent base as a working unit to a single disabled craft. Upon arrival, It could perform hull repairs and top motor overhaul so that the craft could return to its base.

--39--

(2) It could move out as a self-contained unit for about one week and maintain approximately 25 LCVPs and LCMs. This maintenance period could be extended by the establishment of a flow of supplies from the parent base.

(3) The two truck-mounted shops could be divided and each attached to one of the shops of an E10 component to increase the scope of the E10 by about 15 percent.

E9A - MOBILE LVT REPAIR COMPONENT

A highly mobile facility for repairing and salvaging amphibious tractors. The unit shops were designed to be transported in amphibious tractors and intended to go ashore with one of the early waves of an action. It would make spot repairs to battle damaged LVTs, and generally assist the beachmaster in keeping the beach clear in addition to regular operating maintenance. It was capable of quick dismantling and removal. It was self-sustaining so far as materials, fuel, food and berthing for personnel were concerned for a period of four days.

E10 - STANDARD LANDING CRAFT UNIT -MAINTENANCE COMPONENT

Maintained 60 landing craft (40 LCMs and 20 LCVPs) assuming 20% under repair at all times. Repaired both hulls and engines and maintained six months' supply of consumables.

E10A - LANDING CRAFT SPARE PARTS (SMALL)

This component was designed to be added to an E10 component. It provided six months' supply of hull, machinery and internal combustion engine spare parts.

E11 - PT OPERATING BASE REPAIR COMPONENT

Provided facilities for major hull repair, minor engine repair, and replacement of engines for one operating squadron of PT Boats.

--40--

E12 - PT MAJOR ENGINE OVERHAUL COMPONENT

This component was designed to be added to a Motor Torpedo Boat Operating Base. It provided facilities for the major engine overhaul of four operating squadrons of PT Boats.

E13 - MINESWEEPING EQUIPMENT REPAIR COMPONENT (LARGE)

Would make repairs to, and have available replacements and spare parts for thirteen or more minesweepers. The quantity of material varied according to the number of ships to be served.

E14 - MINESWEEPING EQUIPMENT REPAIR COMPONENT (MEDIUM)

Made repairs to, and had available replacements and spare parts for seven to twelve minesweepers.

E15 - MINESWEEPING EQUIPMENT REPAIR COMPONENT

Made repairs to one to six minesweepers.

E16 - OXYGEN GENERATING PLANT

A plant capable of generating 55-80 lbs. of liquid oxygen per hour, or sufficient oxygen to fill 1,200 - 1,600 standard 220 cubic foot cylinders per month with oxygen at 2,000 lbs. per square inch pressure, suitable for all uses including aviator's breathing.

E17 - ACETYLENE GENERATING PLANT

A mobile acetylene generating and cylinder charging plant, mounted in a van type semitrailer with dolly, capable of continuous generation of a minimum of 500 cubic feet per hour.

E19 - TYPEWRITER REPAIR COMPONENT

Provided facilities for the repair of 50 typewriters per month. Minor repairs could be made to other types of office machines. When assigned to a base at which an Optical Shop (J10) was located, this component would operate in conjunction with that shop and thereby be capable of making major repairs.

--41--

E20 - BASE LVT REPAIR COMPONENT

Provided facilities for the major repair and overhaul of 100 LVTs per month, where the accomplishment of such repair was beyond the scope of the regularly established Army and Marine Corps organic repair and maintenance agencies.

E21 - PT SQUADRON PORTABLE BASE EQUIPMENT

Provided a PT Squadron of from 8 to 12 boats with portable, lightweight repair and operating equipment. It would act as a small temporary base under the direction of the squadron commander where boats could refuel and reprovision, where emergency medical treatment was available, and where a small radio station capable of transmitting one or two frequencies could maintain contact with the nearest operating base.

E22 - LANDING AND PATROL CRAFT REPAIR (MOBILE)

Using the principle of tray-mounted selfpowered tools, this component could be operated in four distinct ways:

(1) As a self-contained unit, it could be established on a beach early in an invasion for combat repairs on all types of landing craft along an extended section of a beach.

(2) It could move with a group of approximately 100 LCMs and LCVPs and handle routine maintenance and minor repairs for a period of about two weeks. The maintenance period could be extended by establishing a flow of supplies.

(3) It could also move in with the first echelon of a large repair base such as a LION and maintain ferries, lighters, and other equipment until the main repair facilities were set up.

(4) In a congested area it could be used in conjunction with, but at some distance from, a large repair facility.

--42--

E24 - CARBON DIOXIDE GENERATING PLANT

A mobile CO2 generating and cylinder charging plant, mounted in a van type semi-trailer with dolly, capable of filling 2 1/2 to 3 standard 30-pound capacity CO2 cylinders per hour.

E25 - MATERIAL RECLAMATION AND RECONDITIONING UNIT- one of the latest components to be developed.

Reclaimed all types of worn-out, broken or damaged machinery and engine parts, restored parts and sub-assemblies to original condition, and specially preserved and packed them for reissue as new parts. It was shore based with shop facilities suitable to the reconditioning operations required, particularly including special facilities for welding, metal spraying and chromium plating to restore parts to size prior to finish machining.

As mentioned in the foregoing, it was necessary to effect changes in design and method of repair in order to cope with the rapid progress of the war. The most pronounced changes in design were toward increasing mobility and flexibility. The first development was the truck mounted repair component called the E9. It consisted of three trucks: (1) spare parts van, (2) carpenter shop, and (3) machine shop. It was designed to repair small landing craft and other internal combustion engine equipment. The practical use of this component was well demonstrated in the Normandy landings. Several were landed and were operating from D+1 Day on, with one of these units being expanded and sent forward to become the major naval repair facility for the landing craft used in the Rhine

--43--

crossing northwest of the Remagen bridgehead.

The next type of mobile repair activity accommodated the amphibious tractor or alligator - the LVT.

This repair unit was called the E9-A and was mounted on trays designed to fit into the LVT(4). Similar developments resulted in the design of the E21, a portable component furnishing base equipment for a PT boat squadron, and the E22, a landing and patrol craft unit mounted on 27 skids or trays, including in addition to shops, laundry and ice cream equipment, two bulldozers or retrievers, a jeep, a LeTourneau crane, a water still and a 75 KW diesel power plant.

A critical shortage of cylinders for the transportation of gases for industry and aviation use led to the development and procurement of self-contained portable plants for the manufacture of the principal gases used at advanced bases. The E16, E17 and E24 functional components were used respectively for the production of oxygen, acetylene and carbon dioxide. In addition to the design of functional components for gas manufacture, the bureau developed equipment which made possible for the first time successful bulk shipment of liquid oxygen by sea and air, and the conversion of this liquid to high pressure gas charged in cylinders at the point of use.

--44--

A summary of the number of components procured from 7 December 1941 to 15 August 1945 appears in Table 53 below.

A review of this table suggests the magnitude of the Advanced Base Program. Its importance cannot be measured quantitatively. It is not an exaggeration to say, however, that without the development of advanced base components and the procurement and shipment of this equipment to advanced areas, the war would have been more costly in terms of men and material, and the war could not possibly have progressed as rapidly to a favorable conclusion.

--45--

GUAM -- ONE OF THE CAPITALS OF THE U.S. NAVY'S "ISLAND EMPIRE"

--46--

AND THEN THERE WERE THE COMFORT AND JOYS OF

SOME PT BOAT BASES.

--47--

TABLE 53

ADVANCED BASE COMPONENTS PROCURED

7 DECEMBER 1941 - 15 AUGUST 1945

(A) COMPONENTS DOMINATED BY BUREAU OF SHIPS

|

Code |

Title |

Quantity |

|

B1 |

Harbor Entrance Control Post |

24 |

|

B2B |

Harbor Patrol |

4 |

|

B4A |

Port Director (Medium) |

15 |

|

B4B |

Port Director (Small) |

31 |

|

B4C |

Harbor Patrol |

35 |

|

B4D |

Beachmaster (Large) |

23 |

|

B4E |

Beachmaster (Small) |

10 |

|

B4F |

Port Director (Large) |

1 |

|

B4G |

Port Director (Medium-Large) |

2 |

|

B5A |

Boat Pool |

58 |

|

C7 |

Visual Station - Operating Base (Large) |

20 |

|

C8 |

Visual Station - Operating Base (Small) |

115 |

|

C19 |

Registered Publication Issuing Office |

14 |

|

E1 |

Ship Repair - General |

5 |

|

E2 |

Ship Repair - Capital Ships |

None |

|

E3 |

Ship Repair - Destroyers |

8 |

|

E4 |

Ship Repair - Submarines |

None authorized |

|

E6 |

Landing Craft Base Repair Component) |

18 |

|

E6A |

Landing Craft Spare Parts - Large ) |

|

|

E8 |

Repair - Small Boat |

32 |

|

E9 |

Repair - Small Amphibious Craft (Motorized) |

65 |

|

E9A |

Mobile LVT Repair Component |

21 |

|

E10 |

Standard Landing Craft Unit Maintenance Component ) |

26 |

|

E10A |

Landing Craft Spare Parts - Small ) |

|

|

Ell |

FT Operating Base Repair Component |

16 |

|

E12 |

PT Major Engine Overhaul Component |

1 |

|

E16 |

Oxygen Generating Plant |

12 |

|

E17 |

Acetylene Generating Plant |

12 |

|

E20 |

Base LVT Repair Component |

3 |

|

E21 |

PT Squadron Portable Base Equipment |

16 |

|

E22 |

Landing and Patrol Craft Repair - Mobile |

None |

|

E24 |

Carbon Dioxide Generating Plant |

2 |

|

P12C |

Fire Protection - Waterfront |

21 |

|

P12D |

Fire Protection - Seadrome |

13 |

--48--

TABLE 53, cont'd.

(B) COMPONENTS

UNDER COGNIZANCE OF OTHER BUREAUS

TO WHICH BUREAU OF SHIPS CONTRIBUTED

|

Code |

Title |

Quantity |

|

A1 |

Administration (Large) |

18 |

|

A2 |

Administration (Medium) |

28 |

|

A3 |

Administration (Small) |

94 |

|

A4 |

Administration (PT Base) |

22 |

|

A7 |

Shore Patrol Company HQ |

20 |

|

D3 |

Tank Farm (Large) |

4 |

|

D4 |

Tank Farm (Medium) |

10 |

|

D19 |

Material Recovery (Large) |

3 |

|

D23 |

Logistics Support Company |

14 |

|

H10 |

Additional Operating Equipment -Landplanes |

50 |

|

H11 |

Additional Operating Equipment -Seaplanes |

40 |

|

H14A |

Aviation Tank Farm (Large) |

13 |

|

H14B |

Aviation Tank Farm (Medium) |

13 |

|

H14C |

Aviation Tank Farm (Small) |

58 |

|

H16A |

Aerological (Large) |

35 |

|

H16D |

Aerological (Arctic) |

None |

|

H23 |

Air Transport Operations (Seaplane) |

5 |

|

J12A |

Net Component (Large) |

5 |

|

J12B |

Net Component (Medium) |

16 |

|

J13A |

Degaussing Component (Large) |

3 |

|

J13B |

Degaussing Component (Medium) |

3 |

|

J13C |

Degaussing Component - Minesweeper Base |

4 |

|

J13D |

Degaussing Component - Submarine Base |

None |

|

J13E |

Degaussing Component for Mobile Unit |

None |

|

N9 |

Base Recreation Component |

40 |

|

P12A |

Fire Protection - Basic |

156 |

|

Q1 |

Rapid Landing Gear |

41 |

|

N1A |

Camp (250 Men) -Tents |

884 |

|

N1B |

Camp (250 Men) - Tropical Huts |

129 |

|

N1C |

Camp (250 Men) - Northern Huts |

83 |

|

N2A |

Camp (100 Men) - Tents |

100 |

|

N2B |

Camp (100 Men) - Tropical Huts |

35 |

|

N2C |

Camp (100 Men) - Northern Huts |

9 |

|

N3A |

Camp (50 Men) - Tents |

46 |

|

N3B |

Camp (50 Men) - Tropical Huts |

28 |

|

N3C |

Camp (50 Men) - Northern Huts |

2 |

|

N4A |

Camp (25 Men) - Tents |

39 |

|

N4B |

Camp (25 Men) - Tropical Huts |

5 |

|

N4C |

Camp (25 Men) - Northern Huts |

6 |

|

N7A |

Camp (1000 Men) - Tents |

76 |

|

N7B |

Camp (1000 Men) - Tropical Huts |

58 |

|

N7C |

Camp (1000 Men) - Northern Huts |

None |

--49--

TABLE 53,

Cont'd.

(C) ESTIMATED PROCUREMENT PRIOR TO INCEPTION OF COMPONENT SYSTEM

|

Equivalent

|

Equivalent Title |

Quantity |

|

A3 |

Administration (Small) |

18 |

|

B5A |

Boat Pool |

18 |

|

C6 |

Radio Station - Airfield (Front Line Combat) |

13 |

|

E9 |

Repair - Small Amphibious Craft (Motorized) Additional |

18 |

|

H10 |

Operating Equipment - Landplanes |

18 |

|

N1A |

Camp (250 Men) - Tents |

104 |

|

Q1 |

Rapid Landing Gear |

17 |

|

C5 |

Radio Station - Air Base (Small) |

4 |

|

C8 |

Visual Station - Operating Base (Small) |

5 |

|

N2A |

Camp (100 Men) - Tents |

5 |

--50--

5. SHIP REPAIR UNITS*

During the offensive phase of World. War II the public began to realize that there is much more to a far-flung naval war than just the shooting. Newspapers began saying that the American answer to the most gigantic logistics problem in naval history -- that of supplying provisions, fuel, ammunition, and repairs for warships far from bases and docking facilities -- was the true "secret weapon" that upset Japanese strategy.

Though this many-edged weapon was many months in the forging, its plan was writ in the fire and chaos of the attack on Pearl Harbor and the dark months that followed it. During the desperate days when the Japanese tide was flooding southward through the Pacific, overrunning island after island, somebody foresaw the ebb of that tide and had the moral courage to prepare for it. The strategic pattern was clear. Jap-held islands would have to be recaptured, one by one; units of the Jap fleet would be engaged whenever and wherever they could be caught; and the enemy merchant fleet would be strangled so that it could not support the outposts of the new Empire of the Rising Sun.

All this had to be done with a Navy far from home;

indeed, often far from ports of any sort. This meant that every striking force

of the Navy must constitute an advanced naval base in itself And so, as the

Japanese tide began to recede, and the islands began to be reconquered,

tenders and repair ships and other ships with specialized duties became an

important part of the battle fleet.

*In part adapted from an article by Lt. R. E. Williams, USNR, in the "United States Naval Institute Proceedings" dated March 1946.

--51--

Repair ships steamed in toward conquered islands even before the famed Seabees could get ashore to begin their construction of shore installations. The repair crews aboard those floating shops began their work of servicing and repairing everything from combat vessels to amphibious tanks the minute the anchors of their ships touched bottom in coral lagoons or malarious roadsteads. As the fleet advanced slowly, pushing the enemy back step by step toward his homeland, other repair crews went ashore on reconquered islands and set up shop on a more stable basis. In the meantime the combat arm of the fleet was moving northwestward and the repair ships -- the ADONIS, the JASON, the LUZON, and the other ugly ducklings of the Navy -- followed in its wake, patching up battle damage as fast as the Japs could inflict it.

Big ships, badly hurt, might return to one of the island bases. There an advanced base sectional dock — literally a mobile dry dock, and a device new to the Navy -- might help to overhaul a ship near the scene of action, or to effect temporary repairs so she could make it safely back to her home port. By use of these advanced base sectional docks, generally known as ABSDs, many a ship was spared a time-consuming trip back to a mainland port for repairs; indeed many a ship was saved by them.

The circle of Japanese domination grew smaller and weaker, but there still remained a broad area, even at the last, in which the surface ships of the United Nations could strike only spasmodically, and it was in that area that the Japanese were most sensitive to attack,

--52--

for it was over those waters that their lines of communication ran, dependent upon their attenuated mercantile marine and their rapidly dwindling escort vessels. Upon the fringe of this circle the tenders and the repair ships hovered. Battle-damaged ships were repaired and resupplied in days, instead of weeks, and were hack in the fray again. Instead of sending them hack to naval bases, the naval bases were taken out to them.

Against this strategic backdrop a mere 20,000 men played one of the most important supporting roles in the war. They were the men who kept the combat ships in fighting trim — the repair crews on repair ships and on almost-forgotten island bases in the rear areas (the Advance Base Components discussed in the proceeding section).

They had no worthy champion to make them glamorous in the public eye, no tangy name to lend romance to their work. They just worked, these men of the "Monkey Wrench Navy".

This program began the war with an handful of men and an idea. Although ship repair gained recognition in pre-Pearl Harbor planning as a specialized function in continental naval establishments, little thought had been devoted to special training for this work in the fleet. The only source of training men continued to be the traditional rudimentary apprentice system whereby men and officers were assigned without any particular selection to such repair bases, ships or tenders as existed. No provision was made for earmarking experienced men for continuation in ship repair work in the course of rotation of sea and shore duty.

--53--

a. PEARL HARBOR AND "THE MONKEY WRENCH NAVY"

Known formally by the prosaic name of "Ship Repair Units", these repair forces had their beginning while a pall of smoke still hung over Pearl Harbor, while fires still smoldered, before anybody really knew how much damage had been done by the Japanese sneak attack. It was merely by fortuity that the Navy already had the nucleus of a Ship Repair Unit at the time of the Pearl Harbor attack. The assembly of two destroyer-repair units had been authorized in June 1941 and the Destroyer Base at San Diego was designated as the place at which the units were to be trained and assembled.

The original plan was to send Destroyer Repair Unit No. 1 to Londonderry, Ireland, to man the Naval Operating Base nearing completion at that time. This base was being built as part of the plan for transferring 50 overage destroyers to the Royal Navy in exchange for the use of naval bases scattered throughout the British Empire. The ultimate destination of Destroyer Repair Unit No. 2 was to be some point in Scotland.

Personnel to man those bases was carefully selected by name from various repair ships of the United States Fleet. Material for the two units, with the exception of diving equipment, was already arriving in the British Isles at the time of the attack on Pearl Harbor. By December 7, 1941, Destroyer Repair Unit No. 1 consisted of 671 officers and men, and No. 2 of some 480 officers and men.

--54--

Almost immediately after the Japanese attack on December 7 the two units were consolidated and sent to Pearl Harbor to assist in the repair and salvage of ships damaged there. All men with artificer ratings were selected for that duty. All commissioned officers and warrant officers of Destroyer Repair Unit No. 1 and all warrant officers of Unit No. 2 were sent.

The first contingent of the Ship Repair Unit arrived at Pearl Harbor just two weeks after the disastrous attack. No arrangements having been made for berthing or messing the 1,100 men, they were forced to sleep in the open on the grass and live on whatever food they could find. Much of it was salvaged from the stores of the sunken vessels until better arrangements could be made.

Among the members of this first Ship Repair Unit were about 30 divers. They were completely equipped, because they had been using their diving gear for training at San Diego, and had not shipped it to Ireland with the other equipment. These men took over the biggest part of the diving job at Pearl Harbor, because only a few divers were in the regular navy yard complement there. Thousands of man hours of feverish underwater labor resulted in only one fatal accident. The arduous and often extremely dangerous work and the results obtained at Pearl Harbor have already been fully discussed in Chapter VII.

Diving equipment was utilized to salvage as much apparatus and as many tools as could be clawed from the sodden bowels of the sunken warships. Everything was scarce, and frequently the repair unit had to

--55--

salvage the necessary tools before it could go ahead with a repair job. Electric motors were salvaged to drive salvaged machine tools and eventually a whole machine shop and an electrical shop were built from these retrieved materials. Much of their office equipment -- desks, typewriters, filing cabinets and other furniture -- came from the sunken ships.

Five months after the first Ship Repair Unit went into action 140 officers and men were detached from it and sent back to San Diego to become the nucleus of a second unit. Meanwhile, the warrant officers of Destroyer Repair Unit No. 2 were detached and sent to Londonderry, the original destination of the group. It was at about this same time that the two units were merged and designated as the Pearl Harbor Salvage Detail.

None of the equipment originally set aside for Destroyer Repair Units No. 1 and No. 2 ever reached Pearl Harbor. Moreover, the new unit never was officially commissioned, which was a drawback, for no maintenance fund was available. Though some funds were available in a roundabout way, the unit never had any of its own. As a result, everything the Ship Repair Unit acquired had to be salvaged from the sunken ships or "procured" through various ingenious means.

For example, much equipment was "acquired" from stores destined for such places as the Dewey Drydock at Manila, which was at that time in Japanese hands. This stock of machinery, according to orders, was

--56--

to be stored at Pearl Harbor, so the Ship Repair Unit worked out a new system of storage. A large warehouse was built, the machinery was uncrated, some person or persons unknown promptly bolted it to the floor, and a new repair shop went into operation in the warehouse, these somewhat irregular methods of getting things done earned the name "Scavengers" for the Pearl Harbor Salvage Detail and its officer-in-charge assumed the irreverential nomenclature of "Jake the Snake". Since those ribald days all Ship Repair Units have acquired an aura of respectability.

As the demand for salvage personnel decreased, the unit was called upon to make many voyage repairs on ships, and in November 1942, the unit became known officially as Ship Repair Unit, Pearl Harbor. Its complement was established as 1,329 officers and men.

At about this same time the repair ship MEDUSA departed from Pearl Harbor, and most of the ship-repair work of the base was left to the Ship Repair Unit, though its equipment was far from equal that aboard the MEDUSA.

b. THE SRU COMES OF AGE.

Throughout the first year of the war and well into the second almost all of the repair work in the fleet was accomplished by crews haphazardly collected and trained only as they might acquire knowledge and skill under the antiquated apprenticeship system.

In the Navy's eyes, however, the Ship Repair Unit had proved its worth by the quick and efficient way in which it solved many of the

--57--