Naval Historical Center Department of the Navy

Operational

Experience of Fast Battleships; World War II, Korea, Vietnam

OPERATIONAL EXPERIENCE OF FAST BATTLESHIPS; WORLD WAR II, KOREA, VIETNAM

Compiled and edited, with introduction and notes, by John C. Reilly, Jr.

Second Edition

NAVAL HISTORICAL CENTER

Department of the Navy

WASHINGTON: 1989

For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Printing Office Washington, D.C. 20402

--i--

Keep them at sea, and they can't help becoming seamen;

but attention is needed to make them learn their business with the guns.

-- Admiral Sir John Jervis, Earl St. Vincent (1734-1823)

Hits per gun per minute/weapons on target per unit of

time is the bottom line in our profession.

-- Vice Admiral Isaac C. Kidd, Jr.

The best protection against the enemy's fire is a well directed fire from our own guns.

-- Rear Admiral David G. Farragut, 1863.

If you want to win your battles take and work your bloomin' guns',

-- Rudyard Kipling, Snarleyow

--ii--

FOREWORD

The fast battleship has returned to the fleet, not as a tribute to nostalgia, but as a powerful and versatile component of our modern surface Navy. The four ships of the IOWA class, now back on active service, bring with them a rich legacy of experience and accomplishment spanning three wars. This heritage is not only a justifiable source of pride and tradition, but also a valuable repository of practical ideas and lessons for today's battleship Navy.

The idea for this publication originated with my brief visit to IOWA in late 1986. At that time, many members of the ship's company expressed curiosity and interest about the role of the fast battleship in earlier years, and a keen desire to have access to concrete, detailed information about their operational experience in Vietnam, Korea, and World War II. The result was the first edition of this compilation, issued in 1987. It was well received, and produced valuable suggestions for improvement. This second edition includes a considerable amount of new material requested by readers. Although modest in scope, it nevertheless represents the Naval Historical Center's continuing commitment to support the operating forces of the Navy, as well as our larger commitment to increase public and professional awareness of the value of naval history.

The documents offered here are, in many cases, firsthand accounts by participants in the actions they describe. Recorded soon after the event, they should not be regarded as infallibly accurate and definitive, but rather as guides to the experiences, impressions, and lessons learned of earlier generations of battleship officers and seamen.

It gives me particular pleasure to offer this historical record to a new generation of battleship sailors. May it help them to acquire and enhance that sense of their heritage that is essential to future progress.

Any work of this kind is the product of many heads and hands. The principal editor and author, Mr. John C. Reilly Jr., Head, Ships' History Branch, is a noted authority on ship types. Without the generous assistance of Mr. Richard M. Walker; Mrs. Kathleen Lloyd; YN1 Julie Howells; YN3 Tom West; Mrs. Margaret Wadsworth; Mrs. Theresa M. Schuster; Mr. Raymond A. Mann; and Mrs. Shelley Wallace, it could not have been completed. FCCM(SW) Stephen Skelley, USS IOWA, provided valuable insight. Special appreciation is due to Mr. Claude A. Browne, Jr., of the Navy Publications and Printing Service, for his skillful efforts on our behalf.

RONALD H. SPECTOR

Director of Naval History

--iii--

[blank]

--iv--

CONTENTS

|

FOREWORD |

iii |

||

|

CONTENTS |

v |

||

|

INTRODUCTION |

vii |

||

|

I. WORLD WAR II |

|||

|

A. NAVAL GUNFIRE |

|||

|

Landing at Casablanca |

1 |

||

|

Bombardment of Nauru Island |

8 |

||

|

Bombardment of Kwajalein |

24 |

||

|

Capture of Kwajalein |

31 |

||

|

Bombardment of Mili |

35 |

||

|

Bombardment of Ponape |

40 |

||

|

Bombardment of Saipan and Tinian |

43 |

||

|

Capture of Iwo Jima |

45 |

||

|

Third Fleet Operations off Japan: Bombardments of Honshu, Hokkaido |

49 |

||

|

B. SURFACE ACTION |

|||

|

Engagement off Casablanca |

59 |

||

|

Battleship Night Action, Guadalcanal |

61 |

||

|

Surface Sweep Around Truk |

68 |

||

|

Battle of Leyte Gulf |

75 |

||

|

Battleship Action, Battle of Surigao Strait |

79 |

||

|

C. |

FLEET AIR DEFENSE |

||

|

Battle of the Eastern Solomons |

87 |

||

|

Gilbert Islands Operation |

90 |

||

|

Surface Sweep Around Truk |

97 |

||

|

Carrier Strike Against Palau |

98 |

||

|

Battle of the Philippine Sea |

100 |

||

|

AA Defense During Fast Carrier Force Operations, Leyte |

104 |

||

|

Battle of Leyte Gulf |

106 |

||

|

Third Fleet Operations in Support of Luzon Landings |

108 |

||

|

Okinawa Operation |

109 |

||

|

Battleship Bombardments of Japan |

111 |

||

|

D. CINCPACFLT BOARD ON SHIP AND AIRCRAFT CHARACTERISTICS |

112 |

||

|

II. KOREA |

|||

|

Extracts from CINCPACFLT Interim Evaluation Reports and Action Reports |

123 |

||

--v--

|

Reports and Studies of Battleship as Gunfire Support Ship: |

|||

|

First Marine Division Reports |

132 |

||

|

First Marine Division Evaluation of Gunfire Support |

134 |

||

|

PACFLT Evaluation Group Analysis of MISSOURI Support |

136 |

||

|

PACFLT Evaluation Group Evaluation of NEW JERSEY Support |

148 |

||

|

Naval Liaison Officer, 8th US Army, Comments to PACFLT Evaluation Group on Gunfire Support |

179 |

||

|

Comments from PACFLT Evaluation Group Questionnaire and Action Reports |

185 |

||

|

III. VIETNAM |

|||

|

Extracts from NEW JERSEY Command Histories, 1968-69 |

191 |

||

|

CINCPACFLT Staff Study: Main Battery Missions of NEW JERSEY and Two 8" Cruisers |

198 |

||

|

IV. WAR DAMAGE |

|||

|

Summary of War Damage to American Fast Battleships |

216 |

||

|

Torpedoing of NORTH CAROLINA by Japanese Submarine I-19 |

220 |

||

|

Bureau of Ships War Damage Report: NORTH CAROLINA Torpedo Damage, 15 Sep 1942 |

222 |

||

|

Bureau of Ships War Damage Report: SOUTH DAKOTA Gunfire Damage, 14-15 Nov 1942 |

230 |

||

|

V. |

GLOSSARY |

235 |

|

|

VI. |

SUGGESTED READINGS |

244 |

|

--vi--

INTRODUCTION

The ships discussed in these pages form the three classes of fast battleships completed for the United States Navy between 1941 and 1944. The IOWA class has rejoined the active fleet as modern surface warships. NORTH CAROLINA, MASSACHUSETTS, and ALABAMA, survivors of the two earlier classes, now serve as memorials to those who built, sailed, and fought them in World War II.

NORTH CAROLINA (BB-55), WASHINGTON (BB-56)

728 feet 9 inches; 46,770 tons at full load; 121,000 SHP; 27.6 knots. Nine 16"/45; 20 5"/38 (10 twin mounts); 1.1" and .50-cal. AA (replaced by 40mm, 20mm AA). Fire control: Main Battery Directors Mk 38 w/Radar Mk 3, later Mk 8, later Mk 13. Secondary Battery Directors Mk 37 w/Radar Mk 4, later Mks 12/22 in combination.

SOUTH DAKOTA (BB-57), INDIANA (BB-58), MASSACHUSETTS (BB-59), ALABAMA (BB-60)

680 feet; 46,200 tons; 130,000 SHP; 27.8 knots. Nine 16"/45; 20 5"/38 (16 in SOUTH DAKOTA, built as Fleet Flagship); 1.1" and .50 AA, later 40mm, 20mm AA. Fire control as in NORTH CAROLINA.

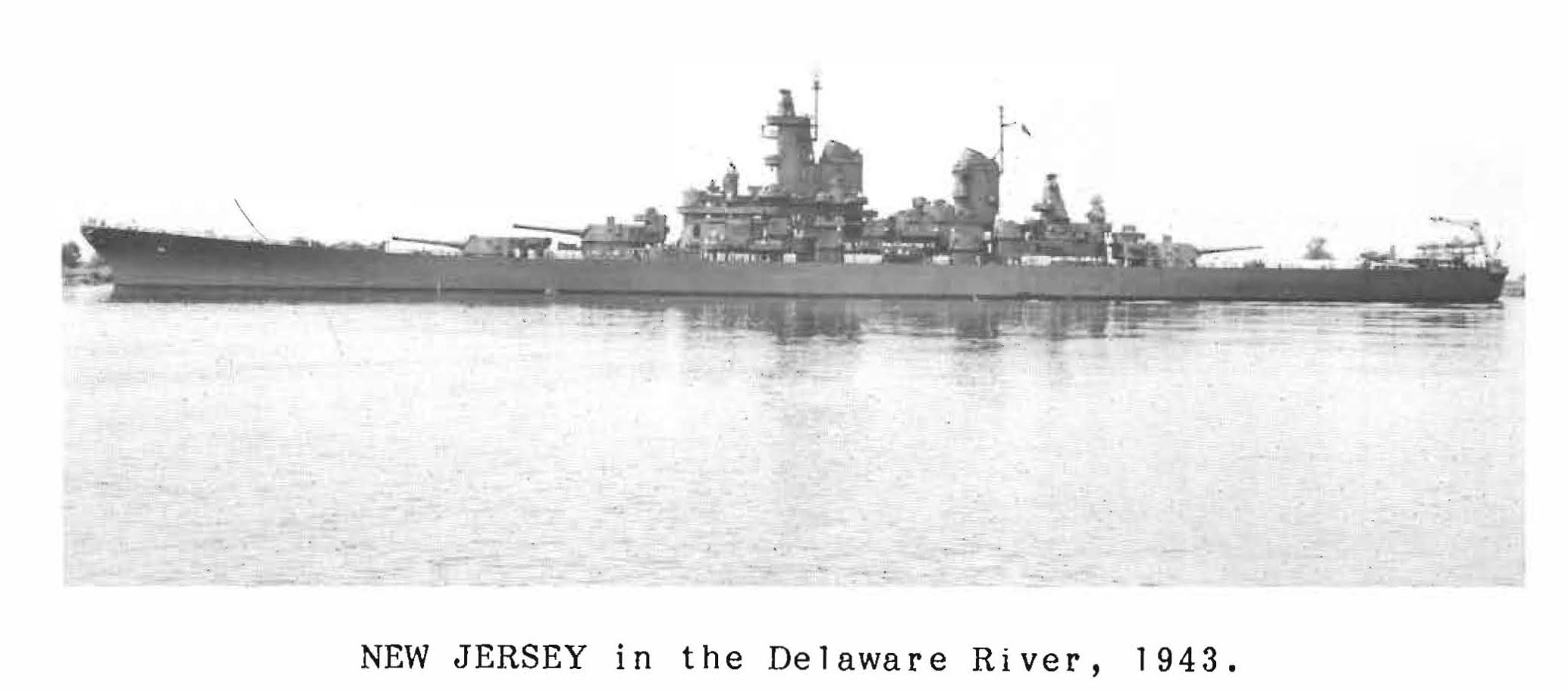

IOWA (BB-61), NEW JERSEY (BB-62), MISSOURI (BB-63), WISCONSIN (BB-64) 887 feet 3 inches; 57,540 tons; 212,000 SHP; 32.5 knots. Nine 16"/50; 20 5"/38; 40mm, 20mm AA. 20mm removed, Korea; 40mm removed from NEW JERSEY, Vietnam. Fire control as in NORTH CAROLINA; Radar Mk 25 on Directors Mk 37 after WW II. ILLINOIS (BB-65), KENTUCKY (BB-66) begun, but never completed.

--vii--

Five ships of the MONTANA (BB-67) class (925 feet; 70,500 tons; 172,000 SHP; 28 knots. Twelve 16"/50; 20 5"/54; 40mm, 20mm AA) were authorized in 1940, but canceled in 1943. These would have been enlarged IOWAs, sacrificing some speed for firepower and protection.

A Note on Sources

The documents, and extracts from documents, which make up the body of this work were selected from the holdings of the Ships' History Branch and Operational Archives Branch of the Naval Historical Center. Since the Office of Library and Naval War Records was originally established in 1884, the Navy has sought to collect and preserve the historical record of its operating forces and to make it usable to new generations. We hope that this publication will contribute to that end.

Notes, comments, and interpolations appear in boldface.

Acknowledgements

Without the strong help of the individuals mentioned by Dr. Spec-tor in his foreword, this work could hardly have been begun, let alone finished. My special thanks go to my wife, Anna, who put up with the whole process from beginning to end.

Errors, whether of commission, omission, or interpretation, are solely mine.

--viii--

I.

WORLD WAR II

A.

NAVAL GUNFIRE

Although shore bombardment became a principal task of older battleships in World War II, fast battleships were also called on to take their share of this mission. The new MASSACHUSETTS supported landings in North Africa in 1942 and, through the end of the war in the Pacific, fast battleships conducted gun strikes and furnished fire support for amphibious landings.

Landing

at Casablanca

November

1942

On 8 November 1942 the new and the o1d -- MASSACHUSETTS and TEXAS (BB 35) -- supported American landings in North Africa. MASSACHUSETTS, off Casablanca, dropped 5 hits on the unfinished French battleship JEAN BART and put her one operational 15-inch turret out of action. She later engaged French destroyers, dodged torpedoes and sank two of the attackers. MASSACHUSETTS scored hits on a powerful battery at E1 Hank, but she lacked HC bombardment ammunition and her AP shells did little damage.

MASSACHUSETTS

ACTION REPORT:

It is the consensus of opinion on this ship that JEAN BART only fired five or six salvos during the engagement. ... We know she was hit at least once as the aviator observed it. Before we commenced firing on her she put up a smoke screen ... and kept it over her throughout the day, so that all fire was indirect, and spotting from aircraft was difficult.

Toward the end of the first run I was informed that El Hank had not replied for ... four or five minutes, and the consensus appeared to be that El Hank was out of commission. This ... proved totally in error. El Hank was also covered by a large dust cloud or used a smoke screen. We believe that shells from this force probably temporarily disabled El Hank, causing the crew ... to seek shelter. After we had ceased firing, they repaired whatever damage took place and, through the remainder of the day, continued to fire spasmodically whenever we were in range.

This vessel ceased firing with 16" shells at JEAN BART and El Hank when the ... number remaining was approximately 40%. Later we engaged enemy cruisers and destroyers and used up another 8%.

The final 7 rounds fired at El Hank from ... about 33,000 yards were fired ... to unload the guns through the muzzle. This salvo apparently caused a large explosion and it is possible that it destroyed one of the ammunition dumps.

In the future, if it is intended for men of war to bombard land fortifications, the ships ... must be equipped with bombardment ammunition as armor piercing shells apparently do not accomplish extensive damage unless they make a direct hit.

--1--

DAMAGE INFLICTED BY ENEMY GUNFIRE

1000: Hit at frame 48, port, by an estimated 240mm shell. Angle of penetration about 70°. Shell pierced wooden deck and 60# STS deck and detonated after gouging a hole about one inch deep in the protective (second) deck. "Sail"* coil of Degaussing System ruptured, causing small electric fire which was readily extinguished with CO2. Also, wooden deck at hole started to blaze up, but was brought under control by fog from below and a stream from above. No personnel casualties ..., and only a small amount of structural damage. ...

1057: Hit at frame 107, starboard, by what appeared to be a 240mm shell, striking at an angle of about 40° with the horizontal. The ... shell ... came from the starboard quarter, ...hit the deck, bounced up at an angle of about 40°, ... and detonated about 10 feet beyond. The shell did not penetrate the 60# STS deck ..., but knocked out several rivets and made a dent about two inches deep. ... The shell detonated about six feet above the deck and about eight feet from the bulkhead. Fragments pierced stanchions, 20mm ready service boxes, 25# STS bulkheads ... Smoke from the detonation was sucked down in the engine room but was quickly dissipated ...

(1) JEAN BART - A six-gun salvo landed on the stern of this ship but had no visible effect on her main battery. Numerous near misses were observed, and her main battery was silenced after it had fired four to six salvos.

(4) EL HANK - An ammunition dump ... about 1000 yards southeast of E1 Hank lighthouse appeared to blow up as a result of a direct hit.

MASSACHUSETTS also claimed hits on the Mole de Commerce, alongside which JEAN BART was moored; on ammunition dumps and moored submarines; on a cargo ship in Casablanca harbor; and on CL PRIMAUGUET and four destroyers. Action reports are contradictory; S. E. Morison credits MASSACHUSETTS and CA TUSCALOOSA with sharing the sinking of DD FOUGEUX, and MASSACHUSETTS with later sinking DD BOULONNAIS. MASSACHUSETTS landed five hits on JEAN BART. Two exploded belowdecks; two others penetrated unprotected portions of the hull, but did not meet enough resistance to trigger their fuzes. The fifth round, a dud, hit JEAN BART’s turret and glanced against its barbette, jamming the turret in train and, for practical purposes, putting it out of action.

MAIN BATTERY FIRE CONTROL

Preparing for the battle, the fire control installation was checked and rechecked many times to insure that all possible removable errors were taken out of the system for the purpose of obtaining the smallest possible pattern with the minimum shift in MPI. All reports indicate that, with a few exceptions, the salvos had a pattern of about 2 mils in deflection and ... 200 to 300 yards in range. While engaging ... 1ight for-

*Phonetic alphabet.

--2--

BOMBARDMENT OF CASABLANCA DEFENSES BY

COVERING GROUP

--3--

ces numerous salvos were reported as straddling the target. In deflection the salvo would cover one-third of the ship and extend not over one hundred yards on either side. ... only one salvo ... had an abnormal spread in deflection. This ... was due to one turret not being matched in train. Several salvos ... reported as having excessive range patterns were also traced to mismatching by the gun layers. Nearly all of these salvos came near the end of the engagement and the crew was becoming fatigued. In these instances we had two guns match low. Firing was checked for several minutes, as all targets had been lost in the smoke. ... gun layers were again cautioned about matching pointers. When ... fire was resumed ... salvos then returned to ... normal pattern size.

From this ... we have learned that, during prolonged engagements, the operating crews become fatigued and are, more than ever, subject to... errors and ... casualties. The turret train layers are not under as great a physical strain as the gun layers,* as they steadily follow the pointer. The errors in matching pointers by the train layers can be expected to be normally very small. On occasions where the turrets were not matched at the instant of firing, they were offset by the same amount, which indicated the lag in personal reaction to a rapidly-moving problem. The gun layers have a more difficult problem, in that they are continually bringing their gun to the firing position and, then, back to the loading position. As they tire during the day their reactions become slower and it required a greater time for them to match their pointers. Also, in some instances, their matching was not too accurate. As these salvos are very powerful when they hit, this engagement clearly demonstrates the desirability ... of ... installation of full automatic features in train and elevation in all turrets.

Experiments ... at the Naval Gun Factory in automatic operation versus personal operation clearly demonstrate the fact that men, watching the movements of a dial, fatigue rapidly. It was definitely proven that a man cannot match a moving pointer, within the limits of error required for automatic gun control equipment, for ... much in excess of ten minutes. He will follow accurately for a few minutes, make a break, and then match up again and follow for a short period of time. ...

During the firing we had some difficulty with ... weave in deflection. The cause of this ... has not ... yet been determined. When firing on ... JEAN BART at times, by indirect fire, it was sufficient to move the salvos from just one side of the target to the other. We are hoping that the trouble is entirely within the Stable Vertical and can be corrected in the near future. The only pieces of Main Battery fire control equipment that have given us any trouble at all are the stable verticals. ... .

Automatic Control in Elevation and Train for Main Battery Turrets

During the first phase of the battle ... our primary target was ... JEAN BART. She was lying ... on a bearing ... nearly normal to our mean firing course, which gave us a very narrow target in deflection. In or-

*MASSACHUSETTS'

turrets had not yet been fitted for automatic control.

--4--

der to hit, the turrets had to be very closely matched in train. With the existing conditions of yaw, crosslevel, and ... necessary changes in course to maintain the desired firing ranges, we had a most difficult set of circumstances for hand-matching in train. An error in matching of 5 minutes* would probably mean a complete miss in deflection for an entire salvo. This happened several times. The need for train receiver regulators** is acute, and they should be installed in the turrets at once.

To reduce salvo intervals, continuous level and crosslevel fire is used by this ship. The range pattern, in most cases, is small, and errors of 5 to 10 minutes in matching in elevation have caused salvos not to straddle. Elevation receiver regulators are, thus, a crying need for the 16"/45 ... turrets , as hand matching in continuous level is not adequate.

Setting of Erosion during Battle

The battle was fought in three main phases. During each phase, all guns did not fire on every salvo. In the lulls between phases, it was thus necessary to correct initial velocity for the fastest gun*** and to correct the individual guns to the fastest gun by means of the initial velocity loss correctors in the gun elevation indicators. The turret officers kept track of the shots fired by each gun so that this procedure was possible. The ... shots fired per gun varied from 66 to 115 for the engagement. Pattern size in range was, thus, kept normal even though erosion varied from gun to gun. This procedure is novel, and is mentioned only as a matter to be kept in mind by plotting room officers so that it will not be forgotten in the heat of battle. All guns should be star-gauged at first opportunity if a considerable number of rounds have been fired.

Indirect Fire

The entire first phase of the engagement was indirect fire on ... -JEAN BART. ... BART was seen indistinctly for only a few seconds some time before tracking was begun. The haze and smoke in the harbor made it necessary to open fire with a range and bearing taken from the plotting table in Main Battery Plot. The only means of correcting the setup in an hour and a half of rangekeeping and shooting was by means of Air Spot. During this time the ship maneuvered radically at speeds above 20 knots, closing and opening the range from 23,200 to 32,400 and reversing course. The rangekeepers were subjected to a test in indirect firing as, probably, never before.

The ship spotters never saw a single salvo fall because of haze and smoke. The air spotters were thus required to spot in range and deflec-

*Minutes of angle, 60 to a degree.

**Device which controls hydraulic train or elevation gear in response to electrical orders from the fire-control system.

***Gun with the highest initial velocity.

--5--

tion. The range spots were good but, during the early salvos, the air spotter had trouble with deflection spots. These deflection spots were all too meager. The usual difficulty of establishing the line of fire was a problem, but the selection of a position from which to make his spots was a far greater one for the air spotter. He was constantly beset by difficulties, inc1uding ... hostile aircraft, antiaircraft fire, smoke, and sun glare. The position finally selected did not afford a good opportunity for estimating deflection during the early salvos.

The range problem during the first phase was not troublesome but the deflection problem was critical.

RADAR

One of the great advancements in the last few years in Naval gunnery has been Radar. By constant practice, we have reached such a degree of perfection with the use of our radars that we depend greatly upon them for ranges during an approach in any kind of weather. If it is hazy, or the weather conditions are such that the target cannot be distinctly seen by the director trainers, we are able to stay on the target with ... high ... accuracy by following the Radar in train. Our radars have held up beautifully ..., even during target practices with reduced velocity charges. But, when we commenced to shoot service velocity charges, ... the radars failed. FC Radar #1, used by Spot One, failed early in the day and was not back in operation until ... practically all of the firing had been completed. FC Radar #2, used by Spot Two, was in and out all day and, at times when both optical and Radar ranges could be obtained, they varied so greatly that the spotter feared the Radar was not reliable for use. During the part of the battle in which we were engaging enemy light forces, neither Main Battery Radar was performing properly. We were set back ... in that we had to operate entirely optically and could only bring a target under fire when it became visible through the smoke. This loss was felt very keenly and was costly in that many more salvos were required ... than would have been necessary if we could have ranged, trained, and spotted by Radar through the smoke. It is urgently recommended that an immediate study be commenced of the effect of shock on all our Radars and equipment.

RANGEFINDERS

All rangefinders ... functioned satisfactorily when it was possible for them to see a target through the haze and smoke, which was seldom. Considerable difficulty was experienced by the rangefinder levellers in keeping their rangefinders level or on the target with the present levelling equipment. The levelling drive installation should be redesigned to remove the excessive lost motion now present. The installation of ... rangefinder stabilizers will greatly improve ranging. It is recommended that these stabilizers be gotten into the ship at the earliest practicable date.

MAIN BATTERY

Armor-piercing projectiles are not suitable ammunition for shore bombardment. When firing at ... shore batteries, time and again we silenced the battery, apparently by driving the crews to cover. If we

--6--

would cease firing or shift to another target for ... 10 to 15 minutes, the battery would again come to life. To do a satisfactory job on a shore installation, high-capacity shells with instantaneously-acting fuzes are required. With such ammunition, these ships can be used effectively for bombarding shore installations in that their range, speed, and maneuverability are such that they can avoid enemy fire while, at the same time, delivering a high rate of fire on the enemy's fortifications. Unless it is possible to close the range sufficiently to insure direct hitting of a shore fortification, the objective should be to neutralize the battery instead of to destroy it as the necessary rates of fire for neutralization are very much less ...

CONCLUSIONS DRAWN FROM EXPERIENCE OF AIR SPOT ....

The two most difficult things about spotting a shore bombardment are (1) seeing the fall of shot, and (2) keeping in mind the line of fire between ship and target, especially when one or the other is out of vision.

Use of Bombardment Ammunition - It was virtually impossible to observe the impacts of AP projectiles which landed on the beach, the docks, or in the city. Water splashes were easy to see, but when the fall of shot was any other place it usually went unseen. I estimate that the action against ... El Hank would have been about fifty percent more efficient, as far as expenditure of ammunition is concerned, had bombardment shells been used.

COMMANDER AMPHIBIOUS FORCE, ATLANTIC FLEET, COMMENTS:

Material Performance. The TORCH operation served as a severe material test for the heavy armaments of the capital ships engaged. Turret crews were called upon to serve their guns for long periods of actual firing time. The performance of turrets of battleships and heavy cruisers was excellent. The few casualties that occurred were ... soon restored. Powder and shell supply was fast, and loading crews performed without casualty. It may be said, in general, that naval gunfire ... gave substantial assistance to the landing forces and aided materially in overcoming enemy opposition.

Fire Control Information. Shore fire control parties and spotting planes should amplify their requests for fire support by including such information as location of own front line, type of target, type of fire required, proposed movements of own troops, and any other pertinent data that will be of service to the ship furnishing fire support. All shore fire control parties should keep the Attack Force Commander informed of targets under fire.

--7--

Bombardment

of Nauru Island

December

1943

To prevent Nauru from being used as a base for attacks on our forces, a task group including two carriers and the battleships WASHINGTON, NORTH CAROLINA, MASSACHUSETTS, INDIANA, SOUTH DAKOTA, and ALABAMA bombarded the island. Since this was the first Pacific gunfire strike carried out by the fast battleships, the firing ships reported their methods and results in detail.

WASHINGTON

ACTION REPORT:

The ship was informed of the probability of the bombardment of Nauru about ten days ahead of the actual bombardment. Preliminary studies of the problem were made during this period. The film on Nauru and the model of Nauru furnished by JICPOA were studied, as were the intelligence folders and current intelligence on the Island. When the Task Force Commander's bombardment plan was received, the Gunnery Department studied the target assignment and prepared a bombardment and salvo plan to cover the assigned areas. The Navigation Department prepared track charts of the proposed targets. By conference between the Navigation Department and the Gunnery Department, the best possible visual and radar targets for navigation were selected and given letter designations in the middle of the alphabet which facilitated identification. The X3JW* and the 3JW* circuits were crossed, with the intention that visual bearings would be available to the Navigator, Flag Plot, Combat, and Main and Secondary Plot. However, due to unforeseen personnel difficulties, none of these visual bearings were put on this circuit. The various plots were kept independently, the Navigator's plot by visual bearings, the Gunnery plots by combination of optical bearings and radar ranges, and Combat plot by radar ranges and bearings. Under the visibility conditions which obtained, it is believed that better plots would have resulted in some stations if visual bearings had been disseminated as planned.

A conference was held during the afternoon of D-2 day, ...attended by the Captain, all Heads of Departments, all senior officers down to the fourth lieutenant in seniority, plus key officers in each department. At this conference, the Navigator presented and discussed the Navigation Plan. The Gunnery Officer presented and discussed the Fire Plan to be used by both batteries, referring frequently to the track chart of the Navigation Plan to point out the expected position of the ship during various phases of the Fire Plan. Each officer present ... was given an opportunity to stress important matters under his cognizance and their relationships to fire control, ship control, and damage control. Care was taken that these discussions brought out clearly the following points:

Own surface forces: in the bombardment formation (Task Group 50.8. 1) and the nearby carrier formation (Task Group 50.8.5). Officers present were fully informed as to ... our own forces they might see or pick up on the radar screen, and what their probable formations might be.

*Ship's internal fire-control telephone circuits.

--8--

Where our own forces might be seen at various times during the bombardment. What our own forces were supposed to be doing at various times.

Time, with relation to H-hour, that such observations might be expected in the various sectors.

As the separation of the forces developed, the carrier force (Task Group 50.8.5) (which, the conference was informed, would probably be within visual and radar range, and on the disengaged side of the bombardment formation to the west and northwest) was widely separated from the bombardment formation (Task Group 50.8.1), and was not encountered, visually or by radar, during the bombardment.

The officers present were informed as to probable enemy forces to be expected: surface, none; and air, moderate, if any enemy planes at all would be airborne. Information was disseminated as to the air plan of our own forces and the probable location of our own aircraft.

The conference was then thrown open to discussion as to various contingencies which might arise, with the warning that comments must be specific and well-prepared, and that a general conversation was not desired.

This conference occupied 51 minutes. After this conference, an instruction period was scheduled for all divisions on D-1 day, at which time officers present at the conference disseminated information to the lower echelons concerned, particularly to junior officers and key enlisted personnel. Special attention was devoted to assuring that all look-lookouts, particularly sky lookouts in Condition ONE, were thoroughly instructed. As a result of this conference, and the subsequent instruction period, all fire control, ship control, and damage control personnel had a clear and complete picture of the prospective operations.

Comment should be made on the great value of the model of Nauru Island furnished by JICPOA. This was used for familiarization of all key officers and enlisted personnel. Lookouts were given an opportunity to examine it through reversed binoculars from the directions from which it might be sighted and approached, and from the relative height of eye which they would be using. This model was also used for familiarization of aircraft spotters with the target areas and the targets assigned to the ship. Air spotting drills were effectively conducted, using this model and white cotton splashes in conjunction with bombardment rehearsal of the main battery.

ALABAMA

ACTION REPORT:

First contact was made on the Island by the various radar equipments as follows:

|

Mark 8 #1 |

48,000 yards, |

bearing 196° T. |

0605 |

|

SG #2 |

45,000 yards, |

bearing 192° T. |

063 1 |

|

SG #1 |

41,000 yards, |

bearing 189° T. |

0638 |

|

Mark 4 #1 & 2 |

40,000 yards, |

bearing 189° T. |

0639 |

--9--

Comment by Radar Officer on Performance of Mark 8:

At 47,000 yards the outline of the cliffs of the Northern end of the Island was quite distinct on high speed scan, and as had been previously planned, was used as reference point for finding on the screen the signal corresponding to Point Able. The following procedure was used in identifying Point Able on radar screen:

(a) Predicted pictures of the Mk. 8 screen had been drawn previously for points along the predicted approach course and firing course. From a study of the Relief Model it has been predicted that the Cantilever* would be picked up bearing 195° T., distance 43,000 yards, so a radar view of the Island to exact scale was prepared of this point for use with high speed precision sweep. It had also been predicted that on this bearing Point Able would be 4,700 yards farther in range than the nearest land and would be on the right tangent to the Island.

(b) With the aid of this information the tracking point was identified earlier than it would otherwise have been. When the Island bore 195° T. a range was taken to the nearest point of land. 4,700 yards was immediately added to this reading, and the range step was then cranked to the resulting range. The Cantilever was tentatively identified at once on the screen by its relatively strong signal, and by its location with respect to other predicted signals.

Tracking was commenced at 43,000 yards, as had been planned, using optical bearings and radar ranges. It is believed, however, that full radar control would have been feasible throughout most of the bombardment. As it was, radar bearing was used intermittently during periods of poor visibility resulting from smoke.

Comment by Spot One:

After initial contact and establishment of bluffs at the NW end of the Island, no tracking points were immediately observed so director was kept trained on right tangent. What was believed to be the Cantilever was picked up by rangefinder at about 44,000 yards. Shortly thereafter, from a comparison of the Mk 8 screen with scaled pictures which had been prepared the tracking point was tentatively identified on the screen and tracking was commenced. At 40,000 yards radar the rangefinder range was 39,900, and the two instruments agreed exactly on the angle of train. This and immediately succeeding comparisons made possible the early and certain identification of the tracking point. Still early in the approach period three pips coming onto the screen were identified as the phosphate plants.

The Mk. 4s were able, chiefly by means of prior instruction of the operators in what to look for, to provide fairly consistent ranges throughout. Secondary battery fired Mk. 8 range line, but checked Mk. 4s continuously and could have used the latter ranges with reasonable success.

*A prominent pier, used as a radar reference point.

--10--

Main Battery

Firing was done in accordance with the fire schedule. Cantilever pier was tracked using forward FH radar and optical bearings and positions plotted each minute on a chart 1,000 yards to the inch. These positions were used to determine ranges and bearings to tracking points in the respective areas. Tracking errors were negligible.

Control spots for coverage were computed using an overlay grid oriented to the line of fire on a large scale chart. These often varied appreciably from tentative control spots listed on the fire schedule. Control spots were chosen to give coverage of assigned targets in accordance with information from plane and top spotters.

Salvo one was fired on "commence firing" from the OTC, and thereafter salvos were fired on time as indicated on the fire schedule. On salvos 2 and 3, turret 3 could not bear, but caught up by firing 3 guns on salvo 4. On salvo 30, turret 2 and 3 each failed to fire one gun necessitating the firing of salvo 32.

Salvo 1 was fired with a total deflection pattern of 400 yards by use of horizontal parallax correctors. The MPI of this salvo was in the center of the assigned area and coverage was almost complete. Subsequent salvos were fired with a 100-yard deflection pattern.

ACTH in range was used as determined for AP projectiles, and was very close to correct. A left ACTH of about 4 mils was used on the basis of reports from other ships, and an additional left ACTH of 5 mils was required throughout.

High order detonation was obtained on all impacts observed.

Secondary Battery

Bombardment was conducted in accordance with prepared procedure and fire schedule, with the following exceptions:

(1) Fire was opened at +20 minutes of Main Battery commence-fire instead of at +17. This ... was necessitated by the fact that the target area was beyond maximum range at +17 minutes.

(2) Computer was shifted to LOCAL, indirect control, twice during firing when Point Able (Cantilever Pier), the tracking point, became obscured to Sky 2* by smoke. In each instance of returning to SEMI-AUTO, no change in bearing solution was evident.

(3) Commencing after 23rd salvo, salvo interval was decreased to 10 seconds. This was done to bring completion of firing to within time allowed.

(4) A 41st salvo was fired ... to expend two remnants resulting from 2 guns having missed a salvo in the shift to a 10-second interval.

*Sky 4: After secondary-battery director. Main 2: after main-battery director. Sky 2: port secondary-battery director.

--11--

ALABAMA secondary battery bombardment doctrine and procedure provides for direct type, indirect type, and offset type control. The doctrine and procedure for offset-type control were selected in advance for the Nauru bombardment after consideration of the factors involved, and were not departed from.

Tracking errors are considered negligible. Mark 8 radar ranges with secondary battery optical bearings were used. Secondary battery optical ranges were transmitted in standby, and were accurate and consistent enough to have been used successfully for the periods in which the tracking point was visible to rangefinder operators. Mark 4 radar operators had been prepared in advance to cope with the problem of ranging on the Cantilever, and were able to provide continuous, though slightly inconsistent ranges throughout. It is believed they obtained the maximum possible performance of the Mark 4 in a problem of this nature.

Control spots were determined from a grid overlay used in conjunction with a large scale plot of the tracking point and target area. Grid was oriented to true bearing of line of sight to Point Able by setting to the bearing obtained from advancing ship's position one minute along the track. Since course was steady throughout firing this was very accurate. No difficulty was encountered in the employment of this method and accuracy obtained is believed to have been satisfactorily high. Postfiring check of ranges, bearings, computation errors and errors of application indicates that the seven subdivisions of the target area were properly covered. This, of course, is not conclusive proof of success, since, under the circumstance of almost no fall-of-shot observations, the accuracy of the gun ballistic and arbitrary ballistic remain unverified. However, in connection with these latter ballistics, past performance leaves no reason to believe the gun ballistic was not accurate, since it was obtained as heretofore. An extremely successful calibration practice, conducted just before the operation with this eventuality in mind, was fired at precisely the range at which bombardment fire was opened. The ACTH then determined was IN 278 yards. IN 250 yards was used on bombardment.

NORTH

CAROLINA ACTION REPORT:

Control

Main Battery

The control procedure followed the standard bombardment procedure used by this ship. The position of the ship relative to the target area was continuously and accurately plotted in CIC by means of information obtained from radar and optical ranges and bearings to prominent landmarks. The rangekeeper continuously tracked the seaward end of the cantilever pier. Spots were applied to the rangekeeper ... to hit the assigned targets. Immediately after firing a salvo, the control spot plus ... arbitrary corrections to hit determined from previous salvos was applied for the next salvo. As aircraft spots were received, they were applied in addition to the a already-calculated offset. This system was simple and effective. Invariably, salvos had to be held for the time

--12--

schedule rather than for "Plot Ready". A salvo interval of 20 seconds greater than the time of flight would have been possible had it been desirable.

Secondary Battery

The secondary battery control procedure followed in general that outlined above for the main battery. While firing in the first target area directors and computers tracked the seaward end of the cantilever pier, offsetting gun train order and gun elevation order by means of control spots in order to hit the desired targets. When fire was shifted to grid areas G1 and G2, it was necessary to shift the point being tracked to a point closer to the target area. A radio tower on top of the hill was selected. At this time heavy smoke obscured the entire target area so that no points were visible, nor were any satisfactory radar targets observed. Combat Information Center furnished the controlling computer with continuous ranges and bearings to the radio tower and firing at the second target area was accomplished in complete indirect fire.

Post firing analysis does not explain the large ACTH in the deflection in main battery firing. The average ACTH in deflection was left 30 mils and in range was Zero. The only possible explanation is that the position of the target area relative to the seaward end of the cantilever pier may have been in error on the charts. A discrepancy of about 400 yards in the chart would have caused this error in deflection. Fortunately, the deflection error was observed, both by the air spotter and by Spot One,* on early partial salvos, fired specifically as spotting salvos, so that few projectiles were wasted.

The aviator reported that secondary battery salvos landed within the main battery area during the early phase. He was unable to accurately determine the positions of fall of shot of the secondary battery projectiles after shift in targets because of the confusion existing in determining own salvos. Other battleships and several destroyers were firing at the landing strip immediately adjacent to our assigned area.

Battery performance was excellent. The main battery fired salvos as planned without variation. Loading times were shorter than those obtain-obtained in drill. Secondary battery salvo intervals were originally 15 salvos were fired. Due to misfires, partial salvos were fired upon the completion of the 40 planned salvos to complete ammunition expenditure.

WASHINGTON

ACTION REPORT:

Fire Control for Bombardment

The fire control installations of these vessels are well designed for firing against surface craft and aircraft, but no adequate facilities have been provided for the handling of the problems of shore bombardment. In this connection almost every ship has designed equipment of

*Gunfire spotting station in forward main-battery director.

--13--

its own. It is felt that better results would be obtained if a few standard items, such as drafting machine scales, were furnished by the Bureau of Ordnance for the control of bombardment. Many action reports on shore bombardments have emphasized the need for charts of uniform scale to be issued in advance of a scheduled bombardment. In view of the many amphibious operations which will be required in this war, it is believed that each battleship and cruiser should be furnished, immediately, a set of charts to this standard scale of all probable early objectives, followed, as soon as possible, by a set of charts for all probable future objectives. Similar charts should be available in the advanced areas for issue to destroyers as required. This ship recommends contour charts of 1,000 yards to the inch and detailed target intelligence charts of 500 yards to the inch.

In connection with the equipment problem, the Pearl Harbor Navy Yard built bombardment tables for both main and secondary battery plot in accordance with designs of this ship. The table in Main Battery Plot, which also serves as a navigational plotting table for Auxiliary C.I.C., has a space allotted for a dead reckoning tracer. With the addition of such a dead reckoning tracer, preferably of the destroyer type, the problem of firing a shore bombardment while the ship is maneuvering would be greatly simplified. The systems used by the Main and Secondary Batteries in this bombardment are described below:

Main Battery

All Main Battery salvos were by indirect fire. A description of the methods used follows: Ship's track was plotted on the bombardment table in Auxiliary CIC (Main Battery Plot) using a scale of one inch to one thousand yards. An exact scale photograph of an Army terrain map of the island, showing previously selected radar and optical points of aim, was used in conjunction with this track. A large drafting machine scale, manufactured by ship's force, enabled the plotter to extend his track to a range of 36,000 yards. Initially the track was plotted using optical bearings of tangents and both optical and radar observations of peaks of the island. When the Cantilever Pier was definitely identified optically and on the Mark 8 Radar scope, Director Two* was placed on the pier and all further tracking was done using optical bearings and radar ranges measured to the pier. The controlling rangekeeper was set up to generate a solution on a reference point near the center of the target area assigned this ship. Prior to the time of opening fire, several setups on this point were given to the controlling rangekeeper, the later ones serving as a check on the accuracy of the earlier information. From the time of commence firing, the controlling rangekeeper was allowed to generate without correction, it being felt that any error which might develop would be rectified by spots.

Target points were selected prior to the bombardment in an attempt to cover the target area thoroughly and at the same time concentrate on primary enemy installations within the area. The target for each salvo was prearranged, and a new range and deflection offset was applied to

*After main-battery director.

--14--

the controlling rangefinder before each salvo using the predicted bearing of the reference point for the time of the salvo. Spots received were plotted on the chart in such a way that the measured offsets for later salvos included corrections for error of previous fall of shot. Responsibility for properly covering the targets rested with the Spot Coordinator, who had full authority to depart from the schedule.

Spots from ... aircraft ... and spots necessitated by the shifting of targets were handled by the Spot Coordinator, using a plexiglass grid. The horizontal scale along the central line, which is the 20,000 yard line of the scale (other range lines run from the origin at various angles to this one) is graduated in 100 yard increments; the scale along the bottom is divided into mils. Deflection spots in yards may be converted to mils by running parallel to the diagonal lines under the range line corresponding to present range is reached and then travelling along a vertical line to the mil scale. The grid is aligned in bearing by a drafting machine. A range scale on the drafting machine arm permits the grid to be positioned in range.

An illustration represents the following situation: The rangekeeper is tracking in generated a reference point "R". Two salvos have been fired in a target "T1". The first fall of shot resulted in a spot of approximately Up 120 yards, left 50 yards and a point "A" was plotted in this position relative to "T1". The second salvo was fired at Point A and resulted in a spot which when plotted from A located Point B. The mid-point between points A and B give the location of a fictitious target. The distance from T1 to this mid-point is the spot to be applied as the result of the two salvos. In shifting to a second target T2, a fictitious target C is plotted in relation to T2, separated by the previously determined spot. The necessary correction from the reference point (R) to point (C) is obtained by placing the zero point of the range scale at the reference point. The grid is then positioned with the central scale line over C. Then the range spot is picked off of the range scale at the central line (in this case Up 1100). By following the proper lines, the deflection spot is seen to be 5 mils right (at a range of 22,000 yards).

Ballistic corrections for height of target and for difference between high-capacity range table values and the values generated by the computer were applied to the spot knobs in such a way that the difference between the total spot counter and the partial spot counter represented the ballistic spot. In this way, a new ballistic could be entered at any time by merely setting it on the dial and pushing the knob in, thereby returning the partial spot dial to zero. The spot for offsetting a target point from the reference point was then set on the partial spot dial without pushing in the knob.

As previously mentioned, Director Two remained on the Cantilever Pier throughout the firing. Director One received designation from the controlling rangekeeper and, hence, was trained on the target area. The field of view from both directors was sufficiently large to enable personnel to see the entire target area as well as the Cantilever, but the blanket of smoke prevented either director from furnishing any usable information regarding the fall of shot. As expected from the experience

--15--

gained in drills, the Mark 8 radar in the plotting room proved itself invaluable for bombardment. When the Mark 8 went out of commission, tracking continued with optical ranges.

The use of a universal drafting machine with a scale sufficiently long to allow plotting at the maximum ranges of the main battery has many disadvantages. The machine is clumsy to handle and lost motion inherent in the instrument becomes magnified when the longer arm is used. Unless some better means is found, it is believed that the method used by the secondary battery to determine offsets, i.e. moving the target area and leaving the ship at the center of a large compass rose, will be adopted.

Secondary Battery

Except for the extra salvos fired at the barracks area, the Secondary Battery used indirect fire from the plotting room (stable element key). Verbal orders to the mounts originated at the controlling director, which was trained on the specific targets during firing. Another director stood by to fire on targets of opportunity. The latter director fired the extra salvos by direct fire on the barracks area upon completion of the scheduled bombardment.

The grid used in Secondary Battery Plot proved effective in simplifying the bombardment problem. This grid, constructed of a sheet of heavy cellulose acetate, is ruled off in accurate one-inch squares and has a wedge for attaching it to a standard drafting machine. The chart of the bombardment target was drawn in ink on the under side of the grid with target locations, possible tracking points, and tangents indicated for ready reference and use. In the center of the grid, a set of circles indicate by their radii the distance the ship travels at speeds of 10, 15, 20 and 25 knots. A small hole is placed at the center of the circles to enable the making of a pencil mark on the paper beneath. The grid is used in conjunction with a large-scale mooring board which has divisions of one degree and 200 yards (to a scale of one thousand yards per inch).

Employment of the grid is as follows: Using the best available source of range and bearing, the grid point is placed over the mooring board in the proper location. These values of range and bearing are obtained by phone from the Main Battery Plot following a "Mark". At the "Mark", a stop watch is started, the point on the chart placed over the range and bearing on the mooring board, and a pencil mark made below the hole in the center of the speed circles. The cellulose sheet is then moved in the direction of the ship's movement until the pencil mark is seen to lie on the circle of the ship's speed. The range and bearing of the target is then read under the target's position on the cellulose sheet and set on the controlling computer. When the stop watch indicates 45 seconds the computer time motor is started, thus commencing generation of range and bearing of the target. Repetitions of this procedure are used for checking. In these checks, at the end of the 45 second period the value sent to the computer should appear under pointers of the range and bearing dials. If ... not ..., a small adjustment is made.

--16--

After opening fire, the cellulose sheet is moved along over the mooring board as ranges and bearings are received from the Ship's Position Talker. When spots are received, they are marked in ink on the surface of the grid to indicate the location of the fall of shot and provide a reference for the application of spots. Using this method, it is easiest to set spots by the present-range and generated-bearing knobs.

The east end of the runway was used as a reference point for air spots, since this was the only clear reference in the assigned target area. As the location of the fall of shot was marked on the surface of the cellulose sheet, the spots required at the computer to move the fall of shot to the next target was immediately apparent.

NORTH

CAROLINA ACTION REPORT:

Detailed information on the target area made possible careful planning and successful execution of this bombardment.

The ability to fire complete indirect fire with no visible point of aim made possible the firing of the secondary battery at the assigned targets in grid Areas G1 and G2.

The performance of material and personnel was up to the standards set in previous actions by this ship and was all that could be expected.

All 5" projectiles were loaded in the upper hoists with their bases down, thereby preventing setting time fuzes off "Safe". There were no prematures from this ship. This procedure is considered sound and is recommended for all future bombardments.

There were no material casualties affecting gunfire. The concussion due to main battery gunfire caused minor damage to certain hull fittings and equipment around the turrets.

WASHINGTON

ACTION REPORT:

Although plane spot was maintained, the heavy clouds of dust and smoke covering the target area, and the interference caused by many ships firing at near or adjacent targets, precluded efficient spotting. In spite of this, however, a careful examination of many excellent photographs taken by the planes of the USS BUNKER HILL, during and after the bombardment firing, show that the targets assigned to this vessel were very effectively covered. I attribute full credit for this to the excellent preparation of the Gunnery Department.

MASSACHUSETTS

ACTION REPORT:

Although the use of these heavy ships for such a mission might be questioned, it is desired to point out that the action herein reported did more to raise the spirits of the crew of this ship than all the efforts put forth in other ways. It is perhaps true that more rounds were fired than were necessary to accomplish the obtainable physical results at the target, but the fact that firing was done at a Jap was enough to renew the men's feeling that they were actually in the war. Perhaps fewer rounds and slower firing would have accomplished as much. It is

--17--

recommended that, in any future campaigns in which it is evident that surface engagement with our like [gunnery action with enemy capital ships] are not probable, that effort be made to carry our at least a token bombardment of some enemy outpost. The use of reduced charges for this purpose is recommended when conditions warrant.

USS SOUTH DAKOTA

AURU BOMBARDMENT

8 DEC. 1943 (+12 ZD)

--18--

SOUTH

DAKOTA ACTION REPORT:

The following specific tasks were assigned to SOUTH DAKOTA...

(a) Fire one 9-gun 16-inch salvo

into a designated area.

(b) Cover two 500-yard squares with 63 16-inch HC

projectiles over a 15-minute period.

(c) At the end of the first 15-minute period, ...take an

additional area, 500 yards square, under fire. ... 63 projectiles and ... 15

minutes were provided....

(d) Cover one 500-yard square with 400 5-inch projectiles.

(e) Destroy all targets of opportunity.

The nine-gun 16-inch salvo was fired with a deflection spread of 300 yards between turrets and a range spread of 600 yards between the high and low guns of each turret. The basis for the size of the spread was the information contained in BuOrd conf. circular letter A47-43.* An examination of the assigned area indicated that sufficient saturation and the effect desired would be obtained by the use of this spread.

The few air spots received indicate that the areas assigned were properly covered. When the main battery was shifted to the second target area in which a structure identified as a radio installation was seen, the air spotter reported that the second salvo in this area demolished

everything at that point. ... No targets of opportunity were fired upon. If the information from the aircraft spotter concerning buildings on the shore remaining intact had been received, the 5-inch battery could have been used to better advantage on these targets.

The following conclusions are drawn from the results of this action:

(a) Lacking an enemy surface target, this bombardment is believed to have been an extremely valuable influence in drawing the units of the fast battleship type of combatant vessel together as a mutual supporting and effective fighting group. The intangible effect on the temperament and morale of personnel is equally important. It is expected it will manifest itself in a greatly increased interest in the individual's job, an increased desire to do damage to the enemy and increased fighting efficiency.

(b) In future bombardments, where the opposition is light, the fire plan should be much more deliberate. Fire should be checked to allow the smoke and dust to clear away if found necessary. With good spotting from the air spotter it should be possible to demolish any target. It is believed that three-gun salvos are sufficient for any type of target to be encountered.

NARRATIVES

MAIN PLOT:

At 0645 the turrets were trained out to a general relative bearing line and told to get up High Capacity ammunition. At 0648 Main Battery

--19--

Director One identified the cantilever by radar, and both rangekeepers commenced tracking this target. ... At 0650 watches were synchronized with Combat, and the ship's track was started on our plotting table, using ranges and bearings off rangekeeper #2, which was still tracking the cantilever. At 0653 Director One identified their target, optically, as being the cantilever. ...we were ready for spotting. At 0655 order was given to turrets to load and lay. Range was about 30,000 yards at this time. At 0658 rangekeeper #1 was shifted to regenerative setup, and corrections applied to correct solution to point of aim of first salvo. At 0659 turrets ... matched pointers in hand, as previously instructed for the opening salvo. At 0702 ... the first salvo was fired. As soon as possible, salvo #2 was fired, aiming at a point in the water 400 yards short of the target area. Our planes reported salvos ... 1anding on the beach, and the third salvo went out aimed at the gun emplacement on top of cliff in our area.

About this time, the ship came left and turret #3 was forced into the stops. Turrets #1 and #2 continued firing, using 2-gun salvos, and Conn was asked to come right, if possible, to bring turret #3 to bear. Turret #3 was told to stand by to fire two guns per salvo, as soon as she could bear, ...to catch up with the fire schedule. No good spots were received, and we had to assume we were somewhere in the area during the next four salvos. After four salvos, the ship came right and turret #3 was able to reopen fire. The following four salvos were 4-gun salvos, with turret #3 firing two guns per salvo. The 6th salvo was spotted as falling in the water, short of the target area, and an up spot was introduced to cover the building and town area. Fire was laddered across this area without subsequent spots until the supply dump was reached, where about three more salvos were fired. The 19th salvo was shifted, still without any further spots, to the buildings on ... top of the bluff, which were in our area.

After the 22nd salvo, fire was checked while the turrets reset their IV loss, and the rangekeeper was shifted to set up for the Radio Station.... Fire was resumed in about 40 seconds, and a spot of R030 was received on the 24th salvo. Corrections were applied and, after the 26th salvo, our planes reported the target covered with smoke and dust. The gunnery officer ... believed the target destroyed. Three more salvos were fired at this target, after which fire was shifted to ... possible fuel dump, ... which seemed worth taking under fire. Fire was laddered, after about 3 salvos, into this target .... ....The firing was completed at 0733 ....

Throughout the bombardment the spots received were very few and far between, and it was necessary to assume where our fall of shot occurred ...to carry out our time schedule. As best we could, we took all targets under fire, and our shifts were corroborated by some spots and not with others. It seems to me that the poor position of our spotting planes, and ...poor communications with ... overlapping frequencies were largely the cause of so much blind firing.

MAIN BATTERY PERFORMANCE

In general battery performance was excellent. A salvo interval of 46.2 seconds was maintained through the first twenty-two salvos and for the last twenty-three; an interval of thirty-seven seconds was maintain-

--20--

ed. On the whole, gun crews and turret officers had no difficulty in maintaining this interval. From salvo twenty-five through salvo thirty-seven, the salvo interval averaged 29.5 seconds, and in some cases was as low as 15 seconds. Despite the reduction of time between salvos, gun crews had ample time to make good smooth loads, and there were no gun room or loading casualties which caused a gun to miss a salvo.

SECONDARY BATTERY PERFORMANCE

The 5" battery was scheduled to open fire at H+1 time, with point "Able"* at 17,000 yards. Actually, the battery commenced firing at H+20, with point "Able" at 16,000 yards. Eight-gun salvos at 15 second intervals were used.

The first salvo was offset to hit in the water in grid square Option* One, and the splash was sighted in this square. Thenceforth the MPI was shifted continuously to cover the assigned area. Spotting plane observations confirm the fact that the area was covered, with no stray salvos except near the end of the bombardment when several bursts were seen on the bluff in areas Prep* and Queen* Five.

Observation from Air Defense and Directors was limited by smoke and dust over the target. However, the cantilever pier and the cleared area along the northwest landing ship were usually visible and were used to judge the location of the bombardment area. Tracers could be followed until lost in the smoke of the target, and they seemed to be headed the right direction.

After approximately 30 salvos, the interval was reduced to 12 seconds and after salvo #36 rapid continuous fire was used to complete the bombardment on schedule. Because of the difficulties of keeping a check of rounds fired during rapid fire, the ammunition allowance was exceeded by 82 rounds before "cease firing" was given.

At the beginning of the rapid firing phase, several splashes were sighted in the area Jig* One, northwest of the cantilever, 1,000 yards short of the 5" area. At this period the only 5" firing was from this ship and the three destroyers astern. The splashes were probably ranging salvos from one of the destroyers, but were erroneously spotted as an error in this ship's 5" fire. The resulting up-spot was late in being applied and probably accounts for the bursts sighted on the bluff beyond the 5" area as reported by plane spotters near the end of the 5" bombardment.

SPOT I

The island was sighted at about 50,000 yards and, shortly thereafter, Hill #9 was identified. Tracking by optics was begun at ranges above 45,000 yards. The island could be seen on the radar screen, but the pips were very weak and no definite point on the island could be identified at ranges above 45,000 [yards] by radar. At about 45,000 yards the cantilever structure was picked up optically, and the point of aim was

*Phonetic alphabet.

--21--

shifted to it. Almost immediately thereafter the cantilever was identified on the radar screen, and tracking proceeded using optical bearings and radar ranges. At about 40,000 yards the cantilever was giving a stronger pip than is normally given by a battleship at the same range.

Director One was the controlling director until just before fire was opened, at which time Director Two took control and Director One followed designation from Plot ... to observe the fall of shot. Shortly after opening fire, Director Two reported ... they had lost the target. Director One trained on the cantilever, and took control for about two salvos until Director Two reported being on the target. Director One then again followed designation from Plot. About the middle of the firing period Director Two reported ... a fuse ... blown in the radar, and Director One again trained on the cantilever but, at about the same time, Director Two reported ... they were again in commission, and Director One trained back and matched designation from Plot for the rest of the firing.

Accurate spotting from Director One would have been impossible, but ... by ... a few salvos, placed in the water at intervals during the firing, it would have been possible to cover the area fairly well if no plane spots had been available.

SPOT II

In future bombardments, where the opposition is as scarce as it was here at Nauru, the fire plan could be slowed up letting the smoke clear ang enabling spotting from directors. With excellent points of aim, such as we had here ..., many more buildings could have been destroyed had we used director fire from Director I.

MAIN BATTERY PROCEDURE

Prior to D-Day, all director and spotting personnel were thoroughly indoctrinated with general information on the target area .... The areas to be fired upon, and all possible radar targets, were marked on... large terrain maps ..., and each director and ... control station was furnished with one copy. Large-scale copies of an aerial photograph ... were made up with a superimposed grid for ... aircraft spotters and spot conversion in Plot. All ... reference points were numbered, and all targets lettered, for ease in designation. A family of curves was drawn up for use in determining IV corrections for various target heights at various ranges. A ... grid, used for conversion of grid spots to range and deflection spots, ... was available for use. The tentative ship's track ... was laid down on the plotting table in Plot and on the DRT in Combat for a check on ship's position. A ... target outline, with all possible tracking points marked, was also drawn in on these plots, so ... position relative to any reference point or target might be taken off these plots. Drills were held, and the entire bombardment rehearsed, several times prior to actual firing.

Main Battery Directors One and Two pick up reference points ... and transmit range and bearing ... to Plot and Combat, where they are used to plot ... ship's position and determine ship's track. As soon as a good reference point is picked up ... and positively identified, both rangekeepers begin tracking it ... to determine any ... current and ... provide a basis for a firing setup on the controlling rangekeeper. If a good reference

--22--

point is not available, the setup for the controlling rangekeeper is taken off the plot of ship's track in Plot. In such a case, data for this track is received from Combat, using information available. If a good reference point for tracking is available, the rangekeeper is controlled by the director until just prior to opening fire, when it is shifted ... to become regenerative, leaving the same problem running. A range and bearing correction is then introduced to shift the theoretical tracking point from the reference point to the point of aim for the first salvo. If no such reference point ... is available, the control rangekeeper is set up using range and true bearing to the target ... taken from the plotting board.

Range and deflection spots are applied to correct for range-table differences between HC and Service [AP] ammunition, and an IV correction is applied to correct for target height. Level and crosslevel are continuously received from the Mark 43 Stable Vertical, and all firing is done using the indirect method .... Throughout the firing, Director Two remains on the reference point, which is continuously tracked by the standby rangekeeper. This solution is used to furnish range and bearing to secondary battery plot ..., and also to check the setup on the controlling rangekeeper. The plot of the ship's position is continued throughout, using information [from the] standby rangekeeper. Director One is controlled, in train, in "Automatic" by the controlling rangekeeper ... to be able to augment air spots by optical spots.

Master

Chief Fire Controlman (SW) Stephen Skelly (Fire

Control Gunner, USS IOWA) comments on SOUTH DAKOTA action report:

--

Fire plan should be much more deliberate.

-- Fire should be checked when target is obscured.

-- With good air spot, it should be possible to demolish any target.

-- 3-gun salvos are sufficient for any target.

-- SOUTH DAKOTA was on the right track long before Saipan [see p. 43]!

Cross-section of a 16"/50 gun. A series of concentric outer cylinders, called hoops, are heated and shrunk around an inner cylinder, the A tube. As the hoops shrink, they tightly grip the cylinders within them. Locking rings hold the hoops in place. The entire gun is then heated and shrunk onto a rifled liner. The assembled gun forms a reinforced cylinder capable of withstanding the enormous pressures of firing.

--23--

Bombardment of

Kwajalein, Marshall Islands

January 1944

Battleships conduct a pre-invasion strike at Kwajalein Atoll. WASHINGTON'S report refers to individual islands by code names; Porcelain, for instance, is Kwajalein Island, the principal island of the atoll; Ebeye Island is Burton. MASSACHUSETTS, on the other hand, uses actual geographic names, and mentions her use of previous combat experience.

WASHINGTON ACTION REPORT:

Porcelain was picked up first by Director One's Mark 3 Radar at 0907 at a range of 42,500 yards, but a suitable visual point of aim could not be picked up until 0944. Visibility up to this time had been very poor due to heavy squalls. At 0950 WASHINGTON reported having a

--24--

KWAJALEIN ATOLL

MARSHALL ISLANDS

KWAJALEIN ATOLL

Contemporary chart showing the code names used to identify Kwajalein’s many

islands.

satisfactory solution. On orders from the Commander Task Unit, one 6-gun and one 3-gun salvo were fired at areas 101, 102, 103, and 104 between 0956 and 1007 by WASHINGTON. Neither of these salvos was effective.

Before the completion of the approach firing several patrol craft were sighted off the north tip of Porcelain. Between 1008 and 1015 the Secondary Battery fired on three of these, sinking one and obtaining hits in two others. On arrival at Point Baker at 1016, the Secondary Battery ceased fire on the patrol craft and commenced bombardment of Burton.

Phase I

Secondary Battery fire against Burton was conducted according to plan. Only a poor coverage of the target resulted due to normal shift of the MPI and lost motion in the elevation system, as the stable element was used as the source of level in this and the following firing. However, several of the beach defenses were straddled, and a small fire was started in the hangar area.

The Main Battery opened fire on Berlin at 1038 with an excellent setup on the small tower in area 307. Despite this, the run on Berlin Island was not satisfactory. The narrow target area combined with shifts of the MPI and the often-stressed doctrine of boldness in spot application caused many salvos to land partially or fully in the water. Hits on the island caused the directors to lose their point of aim from time to time, including the entire period of a 150° turn to the southward leg. Shortly after this turn, one 16-inch salvo was fired at a 4,000-ton tanker behind the northern tip of Berlin but missed. Fire was resumed on Berlin after this salvo and the remainder of the allowed ammunition was effectively expended.

The starboard 5-inch battery had opened fire on the tanker as soon as the turn was completed, obtaining a straddle on the third salvo. Fire was continued at the tanker while the set-up for bombardment of Bennett Island was made. At 1052 the starboard battery was divided to allow fire on Bennett Island. At 1052 the starboard battery was divided to allow fire on Bennett Island. The tanker was seen to be hit and smoking when it was lost to sight about 1056 and all starboard mounts resumed fire on Bennett Island, firing a total of eight salvos.

During the latter part of the firing on Berlin, the off Main Battery Director picked up a large concentration of buildings on Beverly Island. Fire was opened on this island immediately after ceasing on Berlin, as the ship was rapidly moving southward out of the firing area affording best enfilade. The other director and rangekeeper were put on Burton. Some delay occurred while Director One searched for a point of aim on Burton, and effective fire was continued on Beverly even after getting set up on Burton, as considerable damage was being done. A total of 36 rounds were fired on Beverly in rapid fire.

At 1100 the 5-inch battery commenced firing on Berlin without air spot, but with considerably better opportunity for enfilading fire. The target was obscured by smoke from fires started by the Main Battery, however, and the true effectiveness could not be observed.

At 1109, the Main Battery fire was shifted to Burton Island, concentrating on the area surrounding the seaplane service apron. The firing on Beverly had consumed both ammunition and time originally allotted to Burton, and only 24 of the allowed 54 rounds were fired. A

--27--

large fire was started in what is believed to have been a fuel storehouse south of the hangar, which continued to burn throughout the day. Direct hits were observed on buildings surrounding the seaplane apron and on what appeared to be gun emplacements near the ramps. A few overs landed among a group of small vessels anchored near the pier.

By 1110 the 5-inch battery had completed firing on Berlin Island, and another director, which had been tracking its point of aim on Burton Island was given control of the starboard mounts and commenced firing a minute later. The first salvos fell in the assigned area along the northern beach of the island. Fire was then shifted to the hangar area, where fires were started. This firing was considered effective.

Phase II

Because of delays occurring prior to the scheduled bombardment and during the period between phases, the runs to the south of Porcelain were made at a speed of 20 knots instead of 12 knots as planned, and the salvo interval was decreased to one minute. The Main Battery opened fire at 1226 on the target areas on the western end of Porcelain. Salvos were fired in accordance with the fire plan and are believed to have been highly effective. All shoreline target areas from 196 around to 152 were covered. In the attempt to put the MPI of the salvos in the installations near the water's edge many shots fell in the water, but most salvos were at least partially effective, and many were completely so. All strong points as indicated on the intelligence charts are believed to have been hit. Fire was ceased at 1250, having fired 66 rounds. Fires were started in areas 175 and 196 which continued to burn throughout the bombardment.

From 1240 to 1250 the port 5-inch battery fired on beach defenses on the southwestern beach of Porcelain Island, and inland ... where batteries were believed to be located. A large fire was started in the latter area, and beach defenses were well covered. At 1251 course was changed to 240° T. and the starboard 5-inch mounts opened fire on beach defenses on the western end of Porcelain Island. Again the effectiveness was good; fires and explosions were seen in this vicinity by both ship and plane observers. This fire was maintained until 1317.