18

Onward to Addis Ababa

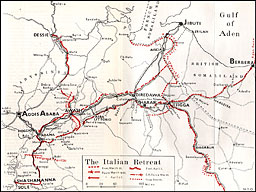

General Cunningham, on 21 March, had received a telegram from General Wavell to say that he saw no military advantage in East Africa Force's going beyond Diredawa unless such a move was likely to end the campaign in Abyssinia. The dangers of becoming too deeply committed--when the forces in the Middle East were stretched almost to the limit--were also pointed out. General Cunningham reckoned that the capture of Addis Ababa was quite possible, and though he was not banking on that resulting in general capitulation he felt that if Eritrea were also taken then the Italians would give in.1

Counting on the use of the Jibuti-Addis Ababa railway within Abyssinia, he assured General Wavell that any advance from Diredawa would not raise any new demands for transport, and the Commander-in-Chief authorized the continuation of the advance.2 On 25 March, the day that Harar fell, 1st S.A. Infantry Brigade Group (less the Natal Carbineers) moved up along the middle road from Jijigga.

Behind Brigadier Pienaar's Brigade Group, no further operations were required in Italian Somaliland and 2nd S.A. Infantry Brigade Mobile Column under Lieutenant-Colonel H. P. van Noorden, which left Nanyuki on 15 March with 642 vehicles and 1,600 men and reached Mogadishu on 22 March, was ordered to move up immediately to reinforce 1st S.A. Infantry Brigade Group. Colonel van Noorden, with no petrol for the long column, had flown up to Advanced Force Headquarters at Gabredarre on 22 March and petrol was provided on 26 March. The force, known as 'Mob-Col', on 27 March set off along the route already taken by 1st S.A. Infantry Brigade Group.

Way off to the east the rest of the infantry of 2nd S.A. Infantry Brigade ('Buc Force') had sailed from Mombasa on 16 March and had begun their laborious disembarkation at Berbera on 22 March, handicapped by lack of usable wharfage, as the piers had been damaged during the British evacuation and again by the Italians. By the time 1st S.A. Infantry Brigade Group moved forward from Jijigga, Brigadier Buchanan had patrols out in all directions from Berbera, and civil administration was being re-established in British Somaliland in spite of the fact that the South Africans had no transport other than what could be commandeered. No. 3 Brigade Signals Company, S.A.C.S. was doing everything possible to restore telephone and other communications in British Somaliland.