'The advantage of time and place in all martial actions is half the victory; which being lost is irrecoverable'. Sir Francis Drake, 13th April 1588.

Early in 1942 Rear-Admiral F. H. Pegram, commanding the South America Division, called at Montevideo in the cruiser Birmingham. He found the Uruguayan authorities now willing, even anxious, to afford full facilities for British naval forces to use their country's harbours. This made matters far easier for our patrols in the South Atlantic. It will be remembered how, in the early months of the war, Commodore Harwood's difficulties had been accentuated by the need to adhere strictly to international law in the matter of warships fuelling in the ports of neutral South American countries.1 As things turned out it was the U.S. Navy which benefited chiefly from these more favourable arrangements, for Admiral Pegram and most of his warships were soon withdrawn from those waters.

With the full maritime power of the United States now available to help protect the ocean shipping routes, it was natural that part of our responsibility for the South Atlantic should be assumed by our Ally. On the 10th of February the whole of the western part of that ocean as far as 40° South was taken over by the U.S. Navy; but the small British cruisers Despatch and Diomede were placed under the commander of the American Task Force, chiefly to maintain British responsibility for the Falkland Islands. A week after these arrangements came into force the Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic, Vice-Admiral W. E. C. Tait, was ordered to transfer his headquarters from Freetown to Simonstown, the latter base being now the more conveniently placed centre of the British strategic zone. He sailed in mid-March, and hoisted his flag ashore at Simonstown on the 26th of that month. In the following August Admiral Tait transferred his headquarters from Simonstown to join up with those of the local air authorities at Cape Town. This change was made to facilitate

co-operation with the South African Army and Air Force. It amounted to the establishment of an Area Combined Headquarters, such as had been found essential at home and on other foreign stations, at Cape Town.2

As a corollary to Admiral Tait's transfer from Sierra Leone to South Africa, Rear-Admiral Pegram was appointed Flag Officer, West Africa, at Freetown. In the following November his command, extending between 20° North and 10° South and as far west as the line marking the American strategic zone, was made a separate naval command.3 In the same month the American zone was moved somewhat to the east to take in Ascension Island, where American aircraft were by that time stationed.

It will be appropriate to mention here that in June 1942 the government of the Union of South Africa announced the amalgamation of its Naval Volunteer Reserve and Seaward Defence Force into one service, soon called the South African Naval Service. Another of the Commonwealth countries thus formed its own Navy. Its ships and men continued to work in close co-operation with those of our own South Atlantic Command.

In the early months of 1942 the British forces in the South Atlantic, a few cruisers and armed merchant cruisers, were generally used to escort WS convoys and to patrol for blockade runners or for enemy raiders. In January anxiety was felt for the Falkland Islands, where it was considered that the Japanese might attempt a sudden landing, so the cruiser Birmingham and A.M.C. Asturias were sent there for a time. To give the impression that we had greater forces in those waters than was actually the case, warships were ordered to appear and disappear off the Patagonian coast with a varying number of dummy funnels in position. Another deceptive ruse was the sailing of imaginary reinforcements from Freetown. That base communicated freely by wireless with them, and it was a nice thought to give the call signs of the battle cruisers Invincible and Inflexible, victors in the Falkland Islands battle of the 8th of December 1914, to this phantom squadron.

No ocean forays were made by German warships during the present phase. Indeed the close watch now kept by ourselves and our American Allies on the northern exits to the Atlantic, and the far more extensive patrolling by our cruisers and aircraft in the central and southern parts of that ocean, would have made such sorties suicidal. Furthermore it was no longer German policy to employ their warships in such a manner. Though some were being used in the Baltic to give support on the flank of the armies advancing into Russia, the principal units were now kept in Norwegian waters

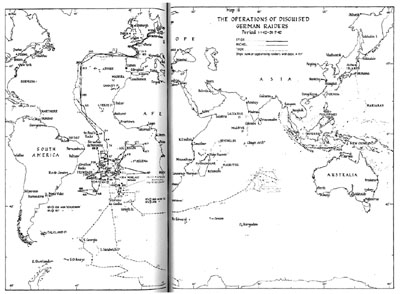

Map 18. The Operations of Disguised German Raiders, 1 January 1942 - 31 July 1942

to protect the country from the invasion which Hitler's 'intuition' had for some months foretold4, or to strike against our Arctic convoys. The U-boats, on the other hand, were reaching out ever further, and in the distant waters had now replaced the warship raiders of the first two years. We will return to their depredations later.

Three disguised merchant raiders left German-controlled waters during the first six months of 1942. They were the Thor (Raider E), which had completed her first successful cruise in April 1941 and had passed down-Channel from Kiel to the Gironde preparatory to starting her second cruise in the following December5; the Stier (Raider J), and the Michel (Raider H). The last two were new entrants to the guerre de course. The Thor sailed from the Gironde on the r 4th of January, but ran into a heavy gale and had to shelter off the north coast of Spain. A week later she reached the centre of the Atlantic, where she turned south and steamed straight down to the Antarctic, to seek the Allied whaling fleets, against which the Pinguin had scored a notable success a year earlier.6 From late February to the middle of March she searched the Antarctic between 30° East and 30° West, constantly using her aircraft to extend her vision; but she met with no success.7 On the 11th of March she headed north again, for a rendezvous at which she was to meet the supply ship Regensburg. On the 23rd, when very close to the rendezvous, she sighted and sank a Greek ship, her first victim in six weeks' cruising. Next day she met the supply ship as arranged, and obtained fuel and stores from her. She then moved north and rapidly found three victims, two British and one Norwegian, all dry cargo ships. On the 10th April, a little further south, her radar picked up a ship at night, and enabled her to surprise and sink the British Kirkpool. On the 16th her aircraft found another ship, but the Thor's captain was uncertain whether she might not be the minelayer and supply ship Doggerbank (about which more will be said shortly) or the raider Michel, both of which might have been in those waters at the time. Before the ship could be identified with certainty contact was lost. The Thor next rounded the Cape of Good Hope and entered the Indian Ocean. She had so far sunk five ships totalling 23,626 tons. After first patrolling the Australian-Cape route without success, she moved to a cruising area some 2,000 miles south of Ceylon, where shipping bound from Australia to Ceylon or India might be met. Earlier raiders had found those waters profitable. There, early in May, she again met the Regensburg with replenishments,

in 22° 30' South 80° East; and on the 10th she encountered the British liner Nankin ( 7,131 tons), bound for Colombo with over 300 persons, including women and children, on board. The liner sent a wireless report, which the raider tried to jam, engaged with her armament and did her best to escape. But it was of no avail, for the Thor was the faster ship. The Nankin was taken in prize, renamed Miollnir and left in company with the Regensburg, which was ordered to take on board as much of the captured ship's cargo as possible. On finding that the Nankin's distress message had got through to Perth, whence it was re-broadcast, the raider moved further south. The captured ship was sent to Japan, where she arrived on the 18th of July, and her passengers and crew were interned. We have no log of the Thor covering this cruise after the 4th of June, but we know that she sank the Dutch ship Olivia (6,307 tons) on the 14th, and captured the Norwegian tanker Herborg (7,862 tons) five days later. The latter was, like the former Nankin, sent in prize to Japan, and was used later as a blockade-runner. In July the Thor captured another Norwegian ship and sent her to Japan; and she sank the British ship Indus on the 20th. At the end of this phase the raider was still in the central Indian Ocean. The end of her cruise and her final destruction will be told in a later chapter.

The Stier (Raider J) had, like the Michel, broken out successfully by the down-Channel route. Her passage from Rotterdam to the Bay of Biscay has already been described, and it will be remembered that our light forces sank two of her escort, but failed to harm the raider herself.8 She reached the Gironde on the 19th of May and sailed next day for the central Atlantic. Her outward passage was not detected.

The Stier's first victim, the British ship Gemstone (4,986 tons), was sunk in mid-Atlantic just north of the equator on the 4th of June.9 Two days later she sank a valuable Panamanian tanker of over 10,000 tons. But this good start by the raider was not maintained. Although she cruised many thousands more miles in the South Atlantic, and was several times refuelled by the tanker Charlotte Schliemann, which in return relieved the raider of her prisoners, she did no more damage in this phase of ocean warfare. On the 28th of July she met the Michel (Raider H) in mid-ocean between Trinidade Island and St. Helena, and there we will take leave of her for the present.

It is worth while briefly to tell the story of the tanker Schliemann, which has just appeared as a raider supply ship. She had arrived at Las Palmas in the Spanish Canary Islands on the day before war was declared, with 10,800 tons of oil fuel embarked at Aruba in the Dutch West Indies. There she remained until early in 1942. Though

her presence and her obvious suitability as a raider or U-boat supply ship was a source of concern to the Admiralty, she seems only to have supplied fuel to one Italian submarine while in Las Palmas. On the 24th of February she left the Canaries to supply the Stier and Michel during the cruises now being described, and between April and August made at least three rendezvous with each of them in the South Atlantic. At about the end of August, after her last supply operation in these waters, she sailed for Yokohama with the raiders' prisoners. She arrived in Japan on the 20th of October. Her next employment was to carry 'edible oils' from Malaya to Japan, but in mid-1943 she reappeared in the Indian Ocean as a U-boat supply ship.

The Michel's departure from Kiel on the 9th of March and her safe passage down-Channel, in spite of attacks by the Dover coastal craft and destroyers, have been mentioned above.10 Her Captain was that same von Rückteschell who had been a U-boat captain in the 1914-18 war and had commanded the Widder (Raider D) earlier in this one. His ruthless methods have already been commented on, and it has been told how he was ultimately indicted and sentenced as a war criminal.11 He was well satisfied by the result of the engagement with our light forces in the Channel. His ship came through unscathed and his crew, many of whom were entirely new to sea warfare, had gained valuable experience. However inexcusable von Rückteschell's conduct may have been towards the crews of his victims, one has to admit his efficiency as a raider Captain. By the beginning of 1942 the guerre de course had become far more hazardous than it had been during the preceding two years; yet his cruise accomplished substantial results. While the Michel was fitting out, Raeder had allowed him great freedom to introduce improvements based on his experience in the Widder. One was to embark a ten-ton motor torpedo-boat with two fourteen-inch stern torpedo tubes and capable of a speed of thirty-seven knots. We shall see later how he made good use of this entirely novel auxiliary. He conducted his whole operations on two principles. The first was to conceal the identity of his own ship at all costs; the second he expressed when he wrote in his diary that ships must be sunk 'with no possibility of "squealing" by wireless'. He greatly favoured attacks on moonless nights.

The Michel reached La Pallice safely on the 17th of March, and left three days later for the Atlantic. Her orders were not to make any attacks until she had reached the southern waters of that ocean, so she took avoiding action on sighting no less than five steamers on her way south. In mid-April she met the tanker Charlotte Schliemann in

25° South and 22° West. The Michel was to live off this supply ship for no less than six months. After fuelling from her von Rückteschell was ready to start work in earnest. On the 19th of April the Michel secured her first victim, the British ship Patella carrying nearly 10,000 tons of fuel oil from Trinidad to Cape Town. She was sunk in a surprise attack at dawn. Four days later the raider's M.T.B. was used for the first time in a night attack on the American tanker Connecticut, also carrying fuel oil to Cape Town. On the 1st of May an endeavour to repeat these tactics against the British Menelaus was unsuccessful. The Alfred Holt ship had a good turn of speed and escaped damage both from torpedoes and from the guns of the raider herself. After meeting the Schliemann again and transferring her prisoners to the supply ship, the Michel attacked and sank the Norwegian freighter Kattegat on the 20th of May by gunfire.

In June the Michel moved north, to the waters south of St. Helena, and there, on the 6th, her M.T.B. made a night attack on the American George Clymer. This ship had broken down on the 30th of May, since when she had been sending out wireless distress messages. It seems likely that the raider intercepted these, as his course took him some 900 miles north direct to the stopped ship's position.12 The distress messages were also picked up at Freetown, and the Commander-in-Chief, South Atlantic, detached the A.M.C. Alcantara from the escort of convoy WS 19 to go to the assistance of the George Clymer. On the 7th the A.M.C. found her still afloat, and rescued her crew. She then remained in the vicinity of the damaged ship in case salvage should prove possible; but it was finally decided to sink her. This proved unusually difficult, and when the Alcantara left on the 12th the derelict was still afloat. The raider, who believed she had sunk the George Clymer, appears also to have been quite close during these events, but she and the Alcantara never sighted each other.

Five days after this incident the Michel sank the British ship Lylepark south of Ascension Island. She next met the Schliemann and also the converted mine-layer Doggerbank. All three ships remained in company for about a week. Having got rid of her prisoners and replenished her supplies the Michel moved east, towards the African coast at Walvis Bay, to try her luck against the main shipping route between Freetown and the Cape; she met with no success, so soon shifted further north, to operate against the same route east of Ascension Island. This brought her three valuable victims in quick succession between the 15th and 17th of July. The first was the Union Castle passenger and cargo ship Gloucester Castle, bound for Cape Town with military supplies. She was sunk by gunfire and

torpedo, and ninety lives were lost. Next day, the 16th of July, an American tanker returning to Trinidad in ballast was sunk, and the Norwegian tanker Aramis was attacked by the M.T.B. and damaged in a night attack. The Aramis made raider reports and did her best to escape, but after a twenty-four hour pursuit the Michel caught and sank her. After these successes von Rückteschell considered it desirable to move elsewhere. He steamed south once more to the usual rendezvous and fuelling position in mid-ocean. There he met firstly the raider Stier, as has already been mentioned, and subsequently the Schliemann; the three ships remained in company for about a week. In the first four months of her cruise the Michel had sunk eight ships of 56,731 tons (if the Clymer be included among her victims); but her career was to last a long time more.

Although no U-boats or surface raiders visited the great focus of shipping off the Cape of Good Hope at this time, the enemy did not leave those waters entirely unmolested. The density of our traffic there is well indicated by the fact that in the one month of May 1942 Cape Town handled a total of 290 Allied ships and Durban 218. Nor were these figures exceptional. On the 13th of March a Dutch ship was mined and sunk off Cape Town. Our intelligence indicated that the former British ship Speybank, which had been captured in the Indian Ocean early in 1941 by the raider Atlantis and taken back to Bordeaux in prize, there to be converted to an auxiliary minelayer, might have arrived off the Cape.13 The intelligence was correct; but we failed to catch her. It is worth briefly following the cruise of the Speybank (now renamed Doggerbank by the enemy). She had sailed from La Pallice on the 21st of January carrying 280 mines, and equipped in addition to act as a U-boat supply ship. She steamed straight to the Cape, and was sighted on the 12th of March by one of our aircraft about 100 miles west of Cape Town. She identified herself as her sister-ship Levernbank, allegedly bound from New York to Cape Town, and was allowed to proceed. That was her first escape, and that night she laid her mines. While actually doing so she was sighted and passed at close range by the light cruiser Durban. She again reported herself as the Levernbank, and was again accepted as such. Next day the A.M.C. Cheshire sighted her further to the south-east, and for the third time a false identity (this time as the Inverbank) was accepted. These lost opportunities led to the Admiralty hastening the introduction of the 'check-mate' system, whereby a warship which intercepted a suspicious ship could call for verification from London, and if verification was denied could at once assume the ship to be hostile. The difficulty in introducing this method of calling the enemy's

bluff lay in the fact that the Admiralty had first to know the daily position of every Allied merchantman; otherwise there was a real danger of friendly ships being sunk by our own forces. It had taken a long time to organise the necessary world-wide reporting and plotting, and although the 'check-mate' system was introduced in eastern waters in October 1942, it was May of the following year before it was made world-wide.

The Doggerbank next cruised to the east into the Indian Ocean. In mid-April she was back off the Cape, and on the 16th and 17th laid more mines off the Agulhas Bank. These too caused us casualties. One merchantman was sunk, and two others and the fleet repair ship Hecla were damaged. In addition to these losses, the mines caused the South Atlantic command considerable anxiety, because besides the many large troopships normally sailing past the Cape in WS convoys, the giant liners Queen Mary, Queen Elizabeth and Aquitania all passed through Cape Town in May. Special arrangements were made to sweep them in and out of harbour.

The Doggerbank returned to the South Atlantic after having made this second lay. In mid-May she there met the blockade runner Dresden, outward bound for Japan. On the 21st of June she supplied the raider Michel in 29° South 19° West, transferred most of her remaining supplies to the tanker Charlotte Schliemann, and embarked 177 Merchant Navy prisoners captured by raiders. With these onboard she sailed firstly for Batavia and thence to Japan, where she changed her varied roles once more and became a blockade runner. The end of her adventurous career did not come until March 1943, when a German U-boat sank her nearly at the end of a blockade running trip.14

German attempts to break though our blockade and bring home valuable cargoes of raw materials were discussed in our first volume, and it was there remarked that the enemy's occupation of the ports of western France in 1940 made such journeys much easier.15 As long as Russia remained neutral a valuable traffic in raw rubber from French Indo-China had been carried to Germany, firstly in Japanese ships to Dairen, and thence by the trans-Siberian railway. But when Hitler's intention to attack Russia became known to his advisers, they had to devise other means for maintaining the supply of a commodity which was essential to Germany's war effort. The Japanese did not at that time want to risk sending their ships to Europe; but they had no objection to carrying cargoes to Japan, where they could be transferred to German blockade runners. The first ship to accomplish such a homeward voyage successfully was the Ermland, which reached Europe on the 3rd of April 1941. After two

more ships (the Anneliese Essberger and Regensburg) had followed the Ermland, the authorities in London considered steps to stop this leak in the blockade. Late in 1941 the Admiralty and the Ministry of Economic Warfare arranged to receive warnings of the movements of all ships likely to be engaged in blockade running, and the Royal Air Force adjusted its patrols in the Bay of Biscay to try to catch them at the end of their journeys. During the first phase of this blockade running, from April 1941 to May 1942, we were occupied with more urgent matters, and the enemy achieved a high proportion of successful journeys. Sixteen ships sailed from the Far East during those thirteen months. They employed many and skilful disguises on passage; but the Elbe was identified by aircraft from the Eagle and sunk, the Odenwald was captured by an American Neutrality Patrol16, one ship turned back and the Spreewald was sunk in error by a German U-boat. Two blockade runners were attacked and damaged by Coastal Command aircraft and one of them, the Elsa Essberger, took shelter in the Spanish port of Ferrol for nearly two months. There she transferred some of her cargo to small ships; and she herself finally reached Bordeaux safely. The balance of success undoubtedly lay with the enemy during this period. About seventy-five per cent of the cargoes despatched, including some 33,000 tons of raw rubber and a like quantity of 'edible oils', reached Germany; and six outward-bound blockade runners carried more than 32,000 tons of cargo, much of it valuable machinery, to Japan as well.17 While on passage the blockade runners were often used to supply U-boats and surface raiders, and to relieve the latter of their prisoners. U-boats invariably escorted them in and out of the Bay of Biscay.

By April 1942 the authorities in London had determined that stronger measures must be taken to stop this traffic, and the various possibilities were reviewed. It was considered that the most economical counter-measure would be for Coastal Command to intensify its patrols and strikes in the Bay of Biscay, as soon as evidence of the approach or departure of a blockade runner became strong. Such operations would be carried out by No. 19 Group and directed from its headquarters at Plymouth; but the provision of aircraft with the necessary range, for it was over 400 miles from the home bases to the approach routes of the blockade runners, proved difficult. In the spring of 1942 the loan of a Whitley squadron and eight Liberators from Bomber Command helped matters, and in June six Lancasters were also temporarily transferred; but long-range aircraft were at this time needed even more to close the 'air gap' on the Atlantic

convoy routes18, and it was impossible to make the patrols off Cape Finisterre a matter of high priority. In fact Coastal Command aircraft only damaged one blockade runner at this time; and as five of its long-range aircraft were lost on such operations the exchange was not profitable. The joint sea and air counter-measures designed to improve results against blockade runners will be dealt with in later chapters.

The distant operations by German U-boats in this phase off the American coast and in the Caribbean have already been described.19 So rich a dividend was reaped in those waters that Dönitz sent out most of his available strength, to the neglect of nearly all other distant operations. The Freetown area had been visited in October 1941, but with small success. Because he expected us, in view of America's entry into the war and the concentration of U-boats in the west, to route more of our South African and South American shipping through Freetown, Dönitz decided in February 1942 to send two U-boats there on a reconnaissance. In March they found a good deal of traffic to the south of that base, and managed to sink eleven ships. But the enemy still considered the western Atlantic by far the most fruitful theatre, so he did not revisit west African waters until the next phase.

The Japanese had meanwhile established their first operational links with their Axis partners, and an agreement with regard to zones of submarine patrols in the Indian Ocean had been included in the Tripartite Pact in December 1941. Later it was several times amended, and in October 1942 the Japanese were supposed only to work to the east of longitude 70° East and the Germans to the west of that meridian. Neither country seems, however, to have regarded itself as rigidly bound by these zones, and U-boats of both nationalities were in fact to be found at work in most parts of the Indian Ocean at different times. It is worth recording that the submarine operations in these waters provided the only known instance of Japanese and German co-operation by land, sea or in the air throughout the war.

In April 1942 five submarines of the I Class (displacement about 2,000 tons) and two auxiliary cruisers (the Hokoku Maru and Aikoku Maru) left Penang for the west. The latter were to act as supply ships for the submarines, as well as themselves carrying out attacks on merchant ships. In the latter capacity they did little damage, since they only accounted for three Allied ships during their cruise. By mid-May the five submarines had arrived south of Madagascar, while others reconnoitred our various bases as far north as Aden. They were seeking warship targets, but failed to find any. They

did however achieve one success, which will be recounted shortly, in penetrating Diego Suarez harbour with the midget submarines which some of them carried.20

During June and July the Japanese submarines worked mainly in the Mozambique Channel. There our shipping traffic was dense; and because anti-submarine escorts were still almost totally lacking it nearly all sailed independently. Admiral Somerville guessed correctly that a supply ship was working with the Japanese submarines, and wanted to send his carriers to find her; but he was prevented from doing so by the need to try to relieve the pressure on the Americans in the Solomon Islands theatre at this time.21 All the Commanders-in-Chief, South Atlantic and East Indies, could do to combat this menace was to divert shipping outside of Madagascar, or route it close to the coast to gain what little surface ship or air cover could be provided. The South African Air Force's Venturas flew patrols for this purpose; but we lost fourteen ships of 59,205 tons in those waters in June, and no less than twenty Allied ships of about 94,000 tons altogether, before the Japanese submarines withdrew in the following month.

At the end of the present phase the Japanese submarines once more reconnoitred our Indian Ocean bases, after which they returned to Penang, except for I-30 which arrived at Lorient on a special mission.

As the tide of Japanese success swept south and west in the early months of 1942, it was natural that Allied eyes should be anxiously turned towards the island of Madagascar. Not only did its geographic position command much of the southern Indian Ocean, but from its excellent harbour of Diego Suarez enemy warships and submarines could menace our Middle East convoy route most dangerously.22 Furthermore the fact that the French authorities in the island owed allegiance to Vichy, whose representatives in Indo-China had so recently and so tamely submitted to Japanese military occupation under the transparent disguise of 'joint defence', increased the potential danger.23 Of that General Smuts was particularly conscious. The Prime Minister too considered 'that the Japanese might well turn up [at Madagascar] one of these fine days', and that 'Vichy will offer no more resistance to them there than in French IndoChina'24; but he and the Chiefs of Staff all felt that a prior strategic requirement was to reinforce India and Ceylon, and that the safety of the latter must take precedence over the occupation of Madagascar. At the end of February the American Chiefs of Staff also

stressed the desirability of denying the enemy the use of Diego Suarez; almost at the same time General de Gaulle came up with proposals of his own. These, however, found no favour with the Prime Minister or Chiefs of Staff, because the Free French did not possess the forces and equipment necessary to ensure success, and de Gaulle's plan was considered unsound in other respects. Mr. Churchill favoured the alternative of doing the job ourselves; but he would not on any account 'have a mixed expedition'. Memories of the fiasco of the mixed expedition of September 1940 were still fresh and, said General Smuts, 'we cannot afford another Dakar'.25 Early in March the Prime Minister still gave Ceylon first priority, but he declared that Madagascar came next and had to be urgently considered. Definite planning was thereupon undertaken, and by the 14th the Chiefs of Staff had an outline ready. The assault force was to be sent out from England in convoy WS 17 to Durban; but the necessary warships had mostly to come from Force H at Gibraltar, because the Eastern Fleet had too many and too serious preoccupations elsewhere. Air cooperation and cover were to be provided from the Navy's carriers, aided by a contribution from the South African Air Force; and the Prime Minister asked Mr. Roosevelt that the United States Navy should send reinforcements across temporarily, to replace the departed Force H. The President, however, preferred that we should replace the Gibraltar force from the Home Fleet, while his Navy would in turn reinforce the latter temporarily. On the 18th of March the decision to go ahead was taken, and the Defence Committee was informed of the plan. Next day the Admiralty signalled the composition of the forces to all naval authorities, and Rear-Admiral E. N. Syfret of Force H, who had already been warned of what was in train, was appointed Combined Commander-in-Chief for the occupation of Diego Suarez. On the 24th Mr. Churchill told General Smuts that 'we have decided to storm and occupy Diego Suarez'26, a decision which the South African Prime Minister immediately acknowledged with gratitude and relief. The rapidity of the steps taken from first conception, through the planning stage, to operational action is to be admired, as is the flexibility of the maritime power which enabled us to mount such an expedition at so great a distance in so short a time, and moreover, at a very difficult period of the war. For reasons of security it was decided that the Free French were to be kept in the dark. Finally President Roosevelt, on the 29th, promised his country's moral support by delivering to the Vichy Government a statement on the purposes of the expedition on the day when the operation, now called 'Ironclad', was actually launched. There had been some

anxiety in London over possible reactions at Vichy, where M. Laval had just come into power, such as the admission of the Germans to the naval base of Bizerta in Tunisia. American support was calculated to reduce such dangers.

The expedition was not a simple affair from the point of view of those responsible for its conduct and success. Diego Suarez is some 9,000 miles from Britain, and important forces, urgently needed elsewhere, were bound to be locked up for some time. Mr. Churchill was determined to limit the commitment to the essential minimum. He knew too well how a requirement such as this could grow, and could absorb increasing numbers of men. 'We are not setting out to subjugate Madagascar', he told the Chiefs of Staff at the end of April, 'but rather to establish ourselves in key positions to deny it to a far-flung Japanese attack'.27 The troops were to go on to India as quickly as possible after the seizure of Diego Suarez, which was the only thing that mattered.

Admiral Syfret was warned to be ready to leave Gibraltar on the 30th of March, and he received certain reinforcements additional to his normal Force H. In all they comprised the Malaya, the aircraft carriers Illustrious and Indomitable (which latter replaced the Hermes when she was sunk in the Indian Ocean on the 9th of April 28), the cruisers Devonshire and Hermione, nine destroyers, half a dozen corvettes and six minesweepers. Most of the corvettes and minesweepers were already in South African waters. All the ships, except those joining later from Admiral Somerville's Eastern Fleet, were to be ready to leave Durban on the 25th or 26th of April. To Major General R. G. Sturges, R.M., commander of the military forces, three Infantry Brigade Groups and a Commando were finally allocated. Captain G. A. Garnons-Williams was appointed Senior Naval Officer for the actual landings. The five assault ships all sailed with convoy WS 17, while the motor-transport and stores left Britain in convoys OS 22 and 23 on the 13th and 23rd of March. Admiral Syfret himself, whose ships were now called Force F, left Gibraltar early on the 1st of April and reached Freetown five days later. There the Illustrious, Devonshire and four destroyers joined him. On the 19th of April they all arrived at Cape Town. Next day Admiral Syfret sailed again, reaching Durban on the 22nd. There the battleship Ramillies, from Kilindini, joined and the Admiral transferred his flag to her. The next week was devoted to making the final preparations, in close co-operation with the government of the Union of South Africa. Admiral Somerville, Commander-in-Chief, Eastern Fleet, now reported his proposals to cover the assault against surface ship interference from the east, and arranged for the

Indomitable to join his colleague's force. Thus were all the instruments of maritime power, 'distributed with a regard to a common purpose, and linked together by the effectual energy of a single will'29, directed towards the critical point. It was, indeed, a classic example of a maritime concentration.30

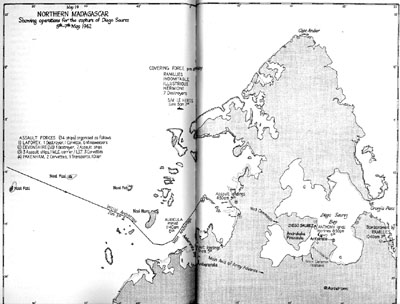

It is now necessary to give the reader some idea of the geography of northern Madagascar, and of the approaches to Diego Suarez Bay, which lies on the east coast near its northern tip. That fine harbour could only be approached from the sea by the narrow Oronjia Pass, three quarters of a mile wide, which was known to be heavily defended.31 The naval base of Antsirane, our primary objective, lies on a peninsula between two of the four small bays enclosed within the main harbour. But Diego Suarez Bay cuts so deeply into the northern tip of Madagascar (Cape Amber) as almost to sever it from the rest of the island. The isthmus thus formed is only some two and a half to six miles wide, and to the west of it lie several bays which, though very difficult of access through reefs and islands, could accommodate a large fleet. These anchorages are only ten or twelve miles in a direct line from Antsirane, and were much less strongly defended than the Oronjia Pass. It was therefore decided that the landings should be made in the bays on the west coast, at the back door to Antsirane. Two convoys from Durban, one slow and one fast, were to meet ninety-five miles west of Cape Amber on the day before the assault, and from there the minesweepers were to lead the ships into their anchorages. The troops were to land in Courrier and Ambararata Bays, seize the coastal batteries, secure a bridgehead and then advance on Antsirane base and airport.32 Meanwhile the cruiser Hermione was to stage a pyrotechnical diversion on the east coast. The main difficulties were caused by 'the unlit and tortuous channels studded with rocks and shoals' through which the ships had to steam to reach their anchorages, and by the strong and unpredictable currents. For the final approach and landings the ships were divided into five groups. The first was under Admiral Syfret himself in the Ramillies; Captain R. D. Oliver of the Devonshire was senior officer of the other four groups, in which were included the assault ships; and Captain Garnons-Williams in the Keren was to take charge of the actual landings.

The convoys left Durban on the 25th and 28th of April and had a calm passage. Not until the 1st of May were final orders to make the assault on the 5th received from London; in Admiral Syfret's opinion this allowed too narrow a margin of time for the final arrangements

Map 19. Northern Madagascar, Showing Operations for the Capture of Diego Sourez, 5th-7th May 1942.

to be made. On the 3rd the Indomitable (flagship of Rear-Admiral D. W. Boyd) and two destroyers of the Eastern Fleet joined Syfret's force. At 3 p.m. next day, the 4th, the traditional naval executive signal to all ships to 'proceed in execution of previous orders' was made, and they formed up for the final approach. The Devonshire was now responsible for the safety of no less than thirty-four ships, some of them large liners like the Winchester Castle, Sobieski, Duchess of Atholl and Oronsay. The last ninety miles were covered almost entirely in the dark, and as the French considered a night passage through the reefs was impracticable, 'the enemy was', in Captain Oliver's words, 'caught unawares'. Buoys were laid as the channel was discovered, and soon after midnight the destroyer Laforey reported its marking completed. She then watched 'with some apprehension' the entry of the transports. Just before 2 a.m. on the 5th they reached the initial anchorage safely, and the assault craft were lowered. Captain Garnons-Williams now took over from Captain Oliver; and the minesweepers swept the eight mile channel to the final anchorage. Though several mines were exploded this did not awaken the defenders. Much to everyone's surprise 'the quiet of the summer night remained undisturbed'. The corvette Auricula, which struck a mine and sank later, was the only casualty.

At 3:30 a.m. the dispersal point was reached, and the assault flotillas moved inshore to the three appointed beaches. The assault took place exactly as planned, and without meeting serious opposition. Meanwhile the Swordfish of the Illustrious, covered by Martlet fighters, had been attacking shipping in the main harbour, while the Indomitable's aircraft dealt with the airport. They too achieved surprise and success.33 Our aircraft also dropped leaflets in which our objects were defined to the defenders, and the return of Madagascar to France after the war was promised; the reply was, however, that the garrison would 'defend to the last'. Admiral Syfret later described such approaches to the Vichy French as useless and even dangerous; for they made them consider that their 'military honour' was involved.

By 6:20 a.m. 2,000 troops were ashore, and the movement of the transports into the inner anchorage continued. Throughout the day troops and equipment landed steadily, in spite of a rising wind and an unpleasant sea, while the clearance work of the minesweepers continued and naval fighters patrolled over the beaches. The attack on the airport had, however, eliminated serious air opposition. By 5 p.m. most of the troops and vehicles were ashore, and Andrakaka peninsula had been seized; but the army was held up by strong

defences some three miles short of Antsirane, which had not been revealed by the photographic reconnaissances carried out before the operation. In consequence the warships, which had been waiting off Oronjia Pass since early in the forenoon, were still unable to enter the bay.

Early in the afternoon of the 6th the Admiral learnt that the assault on Antsirane was held up. 'Things were not going well', and the unpleasant prospect of prolonged operations, which we were most anxious to avoid, was looming up. General Sturges returned on board the flagship, and a night attack on the troublesome defence line was arranged to take place at 8 p.m. Admiral Syfret promised 'any and all assistance', including air bombardment at zero hour. Actually the situation was not as gloomy as was then believed in the flagship; the army had in fact made good penetrations into the defence line, but bad communications had prevented their accomplishments being fully realised.

At this difficult juncture General Sturges asked if it would be possible to land a small party in the enemy's rear on Antsirane peninsula. The suggestion was no sooner made than acted on. The destroyer Anthony (Lieutenant Commander J. M. Hodges) was called alongside the Ramillies, and fifty of the latter's Royal Marine detachment under Captain M. Price R.M. were immediately embarked. At 3:45 p.m. the Anthony cast off and steamed at high speed round Cape Amber to reach the Oronjia Pass. The sea was rough, and the effects of a destroyer's motion on the landing party did not augur well for such a hazardous undertaking. Soon after 8 p.m. the Anthony steamed through the Pass, apparently unobserved until she was almost inside the bay. The batteries then opened fire, and the destroyer's guns immediately replied. It had been hoped that some Commandos would reach the quay where the marines were to land, in time to take the Anthony's wires and help to berth her; but they failed to arrive. A first attempt by Hodges to go alongside was frustrated by a strong off shore wind. He then made a 'stern board' to the quay and by extremely skilful ship-handling, in darkness in a strange harbour and under fire, managed to hold his ship's stern to the quay long enough for the marines to scramble ashore. We cannot here follow the adventures of Captain Price's party in detail. What had started as little better than a forlorn hope ended in an atmosphere of opera bouffe. A few men occupied the French artillery general's house, while others found and seized the naval depot, whose Commandant at once surrendered. British prisoners recently captured were released, including a British agent who was awaiting execution next morning, and Captain Price's chief embarrassment arose from the number of enemies who wished to surrender to him. While the diversionary attack was thus

completely successful the main assault had begun from the west. By 3 a.m. on the 7th the army was able to report that it was in complete occupation of the town and its defences, and that the French naval and military commanders had surrendered. The landing in the enemy's rear, made in the finest tradition of the Royal Marines, certainly contributed greatly to the sudden collapse of resistance.

When, in the early hours of the 7th, it was obvious to him that the night attack had succeeded, Admiral Syfret shaped course to join his other ships off the main harbour entrance. One of the watchful Swordfish from the Illustrious at this time sank the submarine Le Heros, which had reached a menacing position off the northern entrance to the assault ships' anchorage.34 Having arrived off the Oronjia Pass the Ramillies, Devonshire and Hermione formed line, screened by four destroyers, and prepared to bombard the defences. Fire was opened at 10:40, but ten minutes later it was learnt that Oronjia Peninsula and the main harbour defences had surrendered. By 4:30 p.m. the minesweepers had swept the channel into Diego Suarez Bay, and the main body of the fleet then entered. Barely sixty hours had elapsed since the first landings on the west coast. The warships were soon followed by all the transports and storeships, and thus ended an operation of great importance to our control of the Indian Ocean and of the supply route to the Middle East. In his final report Admiral Syfret remarked that 'cooperation between the services was most cordial'. The success may justly be attributed to this, to the Navy's ability to assemble and escort a great concourse of shipping across many thousands of miles of ocean, to recent developments in landing operations and technique carried out under the Chief of Combined Operations, and to the ability of the Fleet Air Arm to provide air cover and cooperation where shore-based aircraft were lacking. The Prime Minister sent Admiral Syfret and General Sturges his warm congratulations.

At the end of May we suffered a misfortune which marred the amazingly small cost at which this success had been achieved. Most of the warships had by then dispersed to other duties, and antisubmarine patrols were weak. The Ramillies, however, had stayed on in Diego Suarez. At 10:30 p.m. on the 29th of May a seaplane unexpectedly flew over the harbour. It was realised that it must have come from an enemy warship of some sort. We now know that it was actually launched by the Japanese submarine I-10. The alert was at once given and the Ramillies weighed and steamed round the bay. In spite of these precautions, between 8 and 9 p.m. on the following evening the battleship and a tanker were both torpedoed. The former was considerably damaged and the latter sank. Two

midget submarines launched from the parent submarines I-16 and I-20 had in fact penetrated into the harbour. Their crews must be given credit for accomplishing a daring and successful 'attack at source'. Not until the 3rd of June was the Ramillies sufficiently patched up to proceed to Durban.

There remained the need to gain adequate control over the remainder of the 900 miles long island of Madagascar, and especially of the sea ports facing the Mozambique Channel. It was at first hoped that this could be accomplished without further military operations, but Vichy French resistance continued, and in September landings were made at three points on the west coast and at Tamatave on the east coast. On the 23rd British forces entered Tananarivo, the capital of the island. Next month operations moved further south until, on the 5th of November, the Vichy French Governor-General surrendered. So ended a campaign which Mr. Churchill has described as 'a model for amphibious descents'.35

About twenty-four hours after the Japanese midget submarine attack in Diego Suarez, a similar penetration was made into the great harbour of Sydney, New South Wales. It seems probable that both operations were planned to divert Allied attention from the Central Pacific, in which the great eastward fleet movements from Japan against Midway and the Aleutians had just started.36 Five submarines, four of them carrying midgets and the fifth a seaplane, took part in the Sydney attempt. The main target was the American heavy cruiser Chicago, but the only casualty was an old ferry-boat, serving as an accommodation ship and moored in the naval base. She received a torpedo intended for the Chicago. None of the enemy midgets returned to their parent submarines. Japanese claims to have sunk the Warspite bore no relation to the truth37, and the night of the 31st of May - 1st of June 1942 is chiefly remembered in Sydney for the pyrotechnics provided by the defending forces, and for the arrival on shore of shells fired by defending Allied warships.

As we look back today at the progress of the whole world-wide struggle, it seems beyond doubt that the month of July 1942 produced the high-water mark of the flood tide of Axis success. In Africa Rommel had reached El Alamein, in Russia the Germans were at Rostov on the Don, in the Pacific the Japanese had occupied the Aleutians and the Solomons, and were threatening the North

American and Australasian continents. In the Indian Ocean our command of the sea was precarious; we had recently been driven out of the whole of Burma, and the overland supply route to China was severed; in the Arctic we had just suffered a serious disaster to one convoy, and in the Atlantic our shipping losses had recently been very heavy. Mr. Churchill has testified how heavily the cares and anxieties of the phase whose story we have now concluded bore on those in high position at the time.38 Yet in the eyes of history it is now clear that, for all the defeats and discouragements that we had suffered and were still suffering, the adverse movement of the balance of success had been slowed, then checked, and finally stopped. In the next phase the tendency of the balance to move back to a central position became marked.

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (VI) ** Next Chapter (VIII)