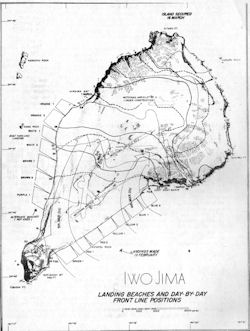

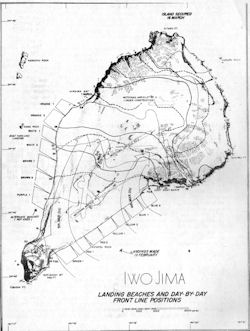

Volcano Islands-IWO JIMA

REASONS FOR SELECTION OF IWO JIMA

A number of small volcanic islands lay on the direct

line of flight from the Marianas bases of our heavy bombers

attacking Tokyo and other industrial cities of Japan Proper. Our

long-range B-29's could make the flight to Tokyo and return but they could not

be given fighter cover for that entire distance. Iwo Jima was about 640 miles

from Tokyo on the north and an equal distance from Saipan on the south. The

island had no barrier reefs and the beach slopes seemed to promise a "dry ramp"

for landing craft. Being only 4.5 miles long and 2.3 miles wide, the entire

island

--173--

IWO JIMA

LANDING BEACHES AND DAY-BY-DAY FRONT LINE POSITIONS

--174--

could be brought within easy range of naval gunfire. It

had three airfields, two of which were operational and a third under

construction. Iwo was one of the few islands of the Volcano or Bonin group that

had enough flat land on its 8 square miles for the construction of airstrips.

The Japanese had heavily fortified Iwo and garrisoned the island with some

21,000 men. Mount Suribachi rises to a height of 550 feet at the southern end of

Iwo Jima and is joined to the rest of the island by a somewhat narrow but

progressively widening isthmus of volcanic sand, along the southeast coast of

which our landings were made.

ORGANIZATION OF THE ATTACK

Some nine hundred vessels were included in the various

Task Groups of the Fifth Fleet and other forces supporting it. Under Task Force

50 were the special groups such as Fleet Flagship (50.1), Relief Fleet Flagship

(50.2), Search and Reconnaissance Group (50.3), Anti-Submarine Warfare Group

(50.7), Logistic Support Group (50.8) and Service Squadron 10 (50.9). Task Force

51 was the Joint Expeditionary Force, Task Force 52 the Amphibious Support

Force, Task Force 53 the Attack Force, Task Force 54 the Gunfire and Covering

Force, Task Force 56 the Expeditionary Troops, Task Force 58 the Fast Carrier

Force and Task Force 9k was Forward Area, Central Pacific. Under Fleet Admiral

Nimitz and supporting the operations were the Submarine Force of the Pacific

Fleet, the Strategic Air Forces of the Pacific Ocean Areas, the North Pacific

Force, the Forward Area Force, the South Pacific Force, the Marshalls-Gilberts

Force, the Service Force of the Pacific Fleet, the Air Force of the Pacific

Fleet, and the Army Forces of Pacific Ocean Areas.

COAST GUARD MANNED VESSELS

Coast Guard manned vessels were included in Task Forces

53 (Attack Force) and Task Force 51 (Miscellaneous Task Groups of the Joint

Expeditionary Force). Thus the USS Bayfield was part of Task Group 53.2

(Transport Group Baker). In Task Group 53.3 (Tractor Flotilla) were Coast Guard

manned LST's 70, 758, 761, 787, 789, 760, 763, 764, 792, 784, 782, 785, and 795.

Under Task Group 51.1 (Joint Expeditionary Force Reserves) was the Coast Guard

manned USS Callaway (APA) and in Task Group 51.3 (Service and Salvage Group) was

the Coast Guard manned LST-766. In the Tractor Flotilla were the ships which

carried troops, equipment and supplies to the objective and put them ashore

during the assault phase. Their total was 30 APA's, 12 AKA's, 3 LSD's, 1 LSV, 46

LST's, and 30 LSM's plus appropriate flagships and escorts. The Joint

Expeditionary Force Reserve comprised some 13 APA's, 1 AP, 4 AKA's, 2 AK's with

5 DD's, and 3 DE's screening. Embarked was the Landing Force Reserve (Third

Marine Division) which was kept in areas removed from the objective until after

D-day. There were 75,144 Landing Force employed in the Iwo Operation of which

570 were Army Assault Troops, 70,647 Marine Assault Troops and 3,927 Navy

Assault Personnel. There were 36,164 Garrison Troops which were kept intact to

take over the defense and development of the island after its capture. These

included 23,830 Army, 492 Marine and 11,842 Navy. The Expeditionary Troops

employed in the operations thus totaled 111,308. The Fourth and Fifth Marine

Divisions executed the assault.

PRELIMINARY OPERATIONS

The minesweepers and the Underwater Demolition Group

arrived at Iwo Jima on 16 February,1945 as part of the Amphibious Support

Group. The minesweepers swept the adjacent waters to within 6,000 yards of the

shore with

--175--

OFF THE FIRE-SWEPT BEACHES OF IWO JIMA,

AMTRACKS LOADED WITH MARINES EMERGE FROM THE DEPTHS OF THE COAST GUARD-MANNED LST-757, AT RIGHT, AND SURGE TOWARD SHORE

--176--

negative results. Fire support ships delivered almost

continuous fire at ranges from 1,800 to 3,000 yards, on pill-boxes, blockhouses,

etc., on the eastern beach area and defenses behind it. This bombardment

continued throughout the 16th, 17th, and 18th. Underwater demolition operations

disclosed no underwater obstacles in the beach approaches and that surf and

beach conditions were suitable for landing. Two batteries of Coast defense guns

were silenced, one on the 17th and one on the 18th. These had been well

concealed and had they not been silenced there might have been disastrous

consequences on D-Day.

THE LANDING

Just before daylight on D-Day, 19 February, 1945, the

Attack Force (TF-53) arrived off the Southeastern beaches of Iwo Jima. The

two Transport Groups reached the Transport Areas off the Southwestern beaches

about the same time and lowering their LCM's and LCVP's, debarked their troops

into them. The LST's and LSM's put their LVT's, LVT (A)'s, and DUKW's into the

water and the initial waves formed up at the Line of Departure off the Southeast

beaches. The first waves struck the beaches at 0900 on a front of about 3,000

yards, receiving only a small amount of gunfire. Heavy mortar and artillery fire

soon developed on the beaches. Beach conditions were bad. The surf broke

directly on the beach, broaching some of the landing craft. Picked up and thrown

broadside on the beach, they were swamped and wrecked by succeeding waves,

sinking deeply into the sand. Wreckage piled higher and higher, extending

seaward to damage propellers of landing ships. Troops from the landing craft

struggled up the slopes of coarse, dry, volcanic sand. The sand bogged down

wheeled vehicles and tracked vehicles moved with difficulty. As soon as the

beachhead was secured LST's and LSM's were sent in to the beaches, but they also

had difficulty in keeping from broaching. Tugs were being constantly employed to

tow them clear when their anchors failed to hold because of the steep gradient

of the beach. Attempts to launch pontoon causeways were unsuccessful because of

the difficulty in anchoring the seaward ends. They broached, were damaged and

sank, or ran adrift, becoming a menace to navigation. The beaches had finally to

be closed to craft smaller than LCT's. Amphibious vehicles were used quite

successfully in evacuating casualties. The beaches were finally cleared of

accumulated wreckage, boats and pontoons were salvaged, and damaged ships

repaired by the Service and Salvage Group. By the end of D-Day a total of 30,000

from both Marine Divisions had been landed. Heavy opposition had developed from

the high ground in both flanks, but the Fifth Marines on the left had advanced

rapidly across the narrow part of the island, capturing the SW end of Airfield

No. 1, then pivoting SW against Mount Suribachi. The Fourth Marines on the right

advanced across the steep and open slopes leading up to Airfield No. 1. They

suffered heavy casualties from machine gun and mortar fire and from mines placed

inland from the beaches.

MOUNT SURIBACHI CAPTURED

Our troops gained from 100 to 500 yards during D plus 1

day (20 February), and captured Airfield No. 1. Some progress was made against

Mount Suribachi and the beachhead was enlarged, making it less vulnerable to

counter attack. The beaches were continually under heavy fire from both

flanks

--177--

UNDER THE MENACING WALLS OF MOUNT SURIBACHI

LANDING CRAFT UNLOAD SUPPLIES ON THE BEACHES OF EMBATTLED IWO JIMA

--178--

and this hampered unloading, causing many casualties and

the loss of considerable equipment, ammunition, and supplies. Foxholes or

trenches dug in the volcanic sand, had to be completely revetted with boards, or

other material to keep them from caving in. During the night enemy tanks and

infantry pressed against our left flank but were repulsed, On D plus 2 and 3,

Regimental Combat Team 28, employing flame throwers and demolitions, advanced

against stubborn opposition and succeeded in surrounding the base of Mount

Suribachi. On the morning of D plus 4, February 23, two battalions climbed to

the rim and surrounded the crater. At 1035 the American flag was raised to its

summit. Its capture eliminated enemy observation and fire from our rear and

permitted freer use of the southern beaches. By the end of D plus 7, all of

Airfield No. 2 was under control and the Third Marine's position in the center

enabled it to support the advance of the Fourth and Fifth Marines through the

more difficult terrain sloping to the sea on either flank. The attack now

continued toward the village of Motoyama and Airfield No. 3. The Fifth Marines

advanced more rapidly than the Fourth, against whom heavy opposition and

difficult terrain held the gain to 1,500 yards in 25 days. The whole advance

therefore, developed into a wheeling movement pivoting on the extreme right. The

result was a general expansion of the beachhead in all directions on the

Motoyama plateau in the center of the island. From here the flanks could be

supported. By D plus 11 (2 March) a 4,000 foot runway had been completed on No.

1 Airfield ready for fighter plane operation and the receiving of transport

planes. By D plus 12 (3 March) the Motoyama tableland and the last of the three

airfields was under our control.

B-29 MAKES FORCED LANDING

The first B-29 to make a successful forced landing on 4

March, demonstrated the value of the newly acquired Airfield No. 1. Two days

later the first Land-based fighters came in and relieved carrier aircraft in

effective close support of troops three days later. The attack was now

concentrated on the eastern shore of the northern plateau but little progress

was made until 8-9 March, when a major infiltration of 500 to 1,000 enemy troops

was wiped out. After this, resistance to our attack towards the beaches greatly

diminished and in the next three days all the eastern coast to within 4,000

yards of Kitano Point, at the extreme north was secured. From 13 March, all

supporting forces were engaged in reducing the defenses of Kitano Point and by

16 March (D plus 25) all organized resistance was declared at an end on Iwo

Jima. Total U.S. casualties between 19 February and 23 March were 4,590 killed,

15,954 wounded, and 301 missing or a total of 20,845. The total enemy dead were

21,304 including 13,234 officially counted and buried and 8,070 estimated sealed

in caves or buried by the enemy. Prisoners totaled 212, including 154 Japanese

and 58 Korean.

USS BAYFIELD AT IWO JIMA

The landing boats from the Coast Guard manned assault

transport USS Bayfield (APA-33) and those from all the other transports,

trying to put men on Iwo Jima beaches on D Day, took a terrific punishment which

far exceeded anything their boat crewmen had experienced the previous summer in

Normandy or Southern France. The entire beach area was littered with wrecked

boats

--179--

OUT OF GAPING MOUTHS OF COAST GUARD-MANNED AND

NAVY LANDING CRAFT ROSE THE GREAT FLOW OF INVASION SUPPLIES TO THE BLACKENED

SANDS OF IWO JIMA

--180--

and wreckage was so thick along some parts of the beach

that the boats were finding difficulty in spotting a space clear enough to hit

land. Japanese mortar emplacements concealed in the sides of Mount Suribachi and

in the high wooded area looking down on the beach from the northeast, were

laying a constant barrage right at the water's edge. Many of the boats were hit

by this barrage. Others had broached and swung sideways so that the crews

couldn't get them into deep water. Salvage boats, which ordinarily kept the

beach clear by refloating or towing out and sinking wrecked craft, were unable

to get into the beach long enough to work. Mortar fire drove them off.

Nevertheless, the young Coast Guard boat crewman, most of them of teen-age, went

into the beach time and again. As they approached the shore the water became

dotted with shell splashes. The Japanese mortars controlled the beach. When the

landing boats came to a halt at the water's edge, no longer a moving target,

they had to lay there, completely exposed, for the time it took their cargo of

men to run out. Other craft, loaded with jeeps, communication equipment and

other material were on the beach for a much longer time. Some of the Coast

Guardsmen manning these boats, did not get back to their ships, Those who did

get back were soon off again with another load.

NO BEACHMASTERS COULD REMAIN ON BEACH

On other assault beaches in previous operations there

had been beachmasters, salvage parties, and beach parties to keep the

landing area clear. There was none of that on D Day at Iwo Jima because no one

could remain on the beach. The Marine assault forces could only keep alive by

moving inland. As a result the landing boats were operating pretty much on the

initiative of their youthful coxswains, When a boat was wrecked it remained on

the beach, a swashing, shifting menace to whatever came in next. Boats going

back to the transport carried casualties, as many as could be brought down to

the water's edge and taken aboard before the fire made it necessary to shove

off. In spite of this the wounded were lying helplessly in shellholes a few

yards in along the entire beach area. The fire was so heavy they could not be

carried down to the boats even when the boats were available. Many of the

hospital corpsmen themselves were wounded. Those of the assault forces who were

alive had to keep moving forward.

NO SAFETY ANYWHERE

A bare, completely vegetationless hillside rising in

terraces, from three to ten feet in height was the beach area. It looked

like a fine gravel dump. Our ships and planes had shelled and bombed the

Japanese mortar emplacements on Mount Suribachi and in the high wooded areas,

but the mortar shells continued to rain down on the beach relentlessly. At the

water's edge were wrecked amphibious tanks, amphibious tractors and a few jeeps.

Beside and under this wreckage was a scattering of dead and wounded. A few

uninjured were trying to salvage a bit of radio or other equipment. The men

lying there were the men who got it the moment they set foot on the beach. To

run, even to crawl, in the soft gravelly volcanic sand was like trying to move

through foot-deep mud. It was impossible to move at much more than a fast

shuffle. Yet to remain near the water's edge any length of time was inviting

certain death from the mortars. It was not much better in from the beach, except

that here the deep holes and ridges dug by gunfire offered some protection. From

time to time, even when

--181--

COAST GUARD LIEUT. (JG) TRUMAN C. HARDIN

PICTURED ABOARD THE COAST GUARD MANNED LST ON WHICH HE PARTICIPATED IN THE

INVASION OF IWO JIMA

--182--

not spurred into movement as the constantly Shifting

line of fire traced and retraced its path, some of the men crawled cautiously

forward up the slope and into another hole. There was nothing to do but go

forward. There was no safety anywhere. The Marines were trying to inch their way

up to the point where they could come to hand to hand grips With the enemy. It

was the only way they could fight. They had nothing at first but rifles and hand

grenades. As yet they had no artillery, no mortars. They had no choice but to

keep going until they could get to the enemy mortars and silence them with

direct assault.

THE LST's MOVE IN

"The coffee-ground black dirt of Iwo island is on the

decks of this LST tonight" wrote a Coast Guard correspondent a few nights

later. "It was tramped in by thousands of rain-drenched, unshaven, dog-tired, U.

S. Marines. Ever since the LST beached they have been moving along a galley

line, carrying trays of steak or hot spaghetti and gravy, cornbread, and paper

cups of coffee.

"The battle for Iwo is only a few hundred yards away.

The ship lies in the brightness of star shells overhead. Beneath her bow

explosive flashes come from a Marine artillery position. A short time ago a man

was hit there by sniper fire. Occasionally the rifles of sentries aboard ship

crack. They are looking for Jap swimmers.

"The Marines are still coming out of the blackness of

Iwo. You hear comments like 'This is the first hot chow I've had since D-Day'

and 'Boy, What a meal!'

"Coast Guardsmen are pulling dry clothes from their

lockers. One man is wearing a white jumper and trousers,-he had given everything

else away. The Marines have left behind their soaking wet battle-dirty clothing.

Some of the crew are washing it and hanging it to dry under blowers, 'You can

get it when you come back aboard' they say.

"Tired men are lying in bunks vacated by Coast

Guardsmen. The wounded are here, too. They lie under blankets in every available

place, on mess tables, in the crew's quarters and in the wardroom, tended by the

ship's doctor.

"'My buddy next to me was hit' one Marine relates. He

said to me 'I think I'm hit.' He was. I said, 'You're darned right you are.' He

told me 'Isn't this a heck of a way to make a living?' Gee, that guy had

courage.

"Below on the tank deck sweating men are loading

howitzer shells into the amtracks which can make the grade in Iwo's loose coarse

black dirt. With each load go ration cans of hot coffee and sandwiches for the

men at the guns.

"Aboard, the Chief Commissary Steward said at last count

he had fed 'at least three thousand men. But they're still coming.' They're

still coming out of the blackness and the grit and the fighting."

--183--

AMTRACKS FROM COAST GUARD-MANNED LST'S

CARRYING FOURTH DIVISION MARINES POKE THROUGH THE WRECKAGE TO CRAWL UP ON THE

BLACKENED SANDS OF IWO JIMA

--184--

LST-761 UNDER FIRE FROM MT. SURIBACHI

The Coast Guard manned LST-761 arrived off the southeast

coast of Iwo Jima at 0730 on 19 February, 1945 as part of Task Group

51.13. By 0750 all LVT's had been launched with their assault personnel and the

LST remained on station until evening, loading and repairing LVT'S. At 2305 she

proceeded to a point 300 yards off Yellow Beach and loaded all LVT's with

ammunition, being under continuous shell from Mt. Suribachi. At 0600 on the 20th

she stood out to her original position off the beach. On the afternoon of the

21st she proceeded shoreward launching causeways and anchoring them 0,000 yards

off Yellow Beach. These were to be used as fuel barges for LVT's and DUKW's. On

the 23rd at 1922 all battle stations were manned in preparation for an enemy air

raid and at 1730 she fired for two minutes at enemy aircraft overhead. On the

24th the LST beached, transferring ashore CB's and their maintenance equipment,

as well as Marines with their LST repair equipment and incidental gear. On the

25th and 26th, due to the heavy seas and wind, the LST was damaged while loading

alongside an AKA and on the 27th while beached she received a near miss on her

starboard side amidship from enemy mortar fire.

LST-782 LANDS DUKW's AT IWO JIMA

The LST-782, Coast Guard manned, was flagship of LST

Unit Six (53.3.9) under Commander W. G. Millington, USCG. This was

included in Tractor Group CHARLIE (53.3.7) under Captain Peterson, USCG, which

in turn was part of Tractor Flotilla (53.3) Captain Brereton, USN. The LST

arrived on station in LST area off Iwo Jima at 0755 on 19th February, 1945 and

at 1250 commenced moving toward the Line of Departure to launch her DUKW's. The

last of the 21 DUKW's was disembarked at 1620 and an hour later the first DUKW

returned for reloading. At 1918 she retired to the Inner Transport area for the

night. The bombardment of Iwo Jima by our ships was evident at all times from

the moment the island hove into view. Battleship, cruiser, and destroyer

bombardment continued at all times. Plane bombardment was almost continuous

during daylight hours but in varying degrees of intensity. The crew witnessed

bombing, rocket assaults and straffing. No air opposition was seen and there was

very little antiaircraft fire. On the 20th unloading at the Line of Departure

was resumed via DUKW's and LVT's. The LCT-1030 was launched without difficulty.

By 1800, 60% of the cargo, 95% of the rations and 30% of the ammunition had been

unloaded. By the 21st the casualties among the DUKW's was quite high with fewer

returning. LCVP's were loaded over the side in response to urgent appeal for

artillery, ammunition, and white phosphorous. On the 22nd the LST began taking

aboard casualties and then beached and completed unloading. While beached every

effort was made to feed all comers. 5,500 cups of coffee with an undetermined

amount of hot food was handed out in twelve hours. The engines had to be kept

going to maintain the LST's position on the unusually steep beach and strong

current parallel to it. There were 7 fathoms of water at the stern. On the 24th

the LST rendezvoused with Task Unit 51.16.3 and departed for Guam.

LST-790 IN KAMIKAZE ATTACK

The LST-790, which was Coast Guard manned arrived off

Iwo Jima on the morning of 20 February, 1945 and about noon headed

for the retirement area southeast of the island and north of Minami Iwo Jima

where she cruised for the night. On the 21st while about 46 miles

--185--

COAST GUARD-MANNED LST UNLOADS AT IWO JIMA

--186--

southeast of Iwo Jima with Task Group 51.5, an enemy plane

dove into the starboard side of LST-477, setting her afire forward with a loud

explosion. About a minute later a second plane dove into the AKN-4 (Keokuk) and

a fire ensued with a loud explosion. Three Japanese planes were now observed

coming from 300° in a shallow glide for the middle of the convoy with motors

out. All ships were already at general quarters and put up considerable AA fire.

One plane came in very low over the stern of LST-809, making firing difficult

except by that ship and was splashed, about 300 yards, on the port side of LST-

790. The two planes pulled out of their dive and out of range, circled the

convoy and seemed to deliberate another attack. Upon closing in they were once

more repelled by AA fire from all ships and faded out of sight, heading north.

The fires on the stricken ships looked very serious at first but they were

extinguished rather rapidly. The LST was again attacked on the 22nd about 2

miles southeast of Iwo Jima, while in company with two other LST's and DE-750.

At 1510 four planes were sighted coming in abreast, with two more astern of

them. All guns of the LST-790, bearing to starboard, opened fire and all four

planes appeared to be hit almost immediately after all our ships had opened

fire. Two turned to their right and splashed ahead of the LST, one exploding in

the air and the other going down after running out about 2½ miles. The third

and fourth planes turned to their left, the third splashing ahead and the fourth

to starboard. Observers claimed that fire from the LST-790 definitely accounted

for three of the four planes. On the 24th the LST beached and unloaded 31 trucks

in 32 minutes. She then commenced unloading pallets of food and water but this

proceeded slowly due to lack of trucks from the beach. On the 26th she retracted

and prepared to take in tow LST-42, which had a damaged rudder, with orders to

beach her at Blue or Yellow Beach. Before this could be accomplished a sea going

tug took over LST-42. The LST-790, unable to find a suitable anchorage, lay to

and cruised for the balance of the day and at night took station with other

LST's to the north of the big ship anchorage. On the 28th the LST sortied for

departure, as part of the TU 51.16.8 for Saipan.

LST-792 HIT BY MORTARS

The Coast Guard manned LST-792 arrived off Iwo

Jima on 19 February, 1945 after an uneventful trip from Hawaii

carrying 70 Army troops and 360 Marines with their equipment. A tremendous

bombardment was followed by the landing of the first waves. On 24 February she

beached at dusk to unload cargo and shortly after dark underwent one of the

first air raids on the island. The crew opened fire and soon after received

thirteen mortar hits and had to retract from the beach to prevent further damage

to ship and personnel. Five men were wounded, and two were recommended for the

Purple Heart. While beached at Iwo Jima, Mr. Rosenthal, the A.P. photographer

who snapped the now immortal picture of the flag raising on Mt. Suribachi came

aboard for a meal, having been on the beach since early in the landing. On the

28th the LST returned to Saipan,

LST-784 DUKW's DO NOT RETURN

The crew of the Coast Guard manned LST-784 saw the

battle for Iwo Jima early on the dark morning of 19 February, 1945

as star shells were dropped over the island by bombarding fighting ships. At

0800 on D-Day the LST swung into position off the beach and maneuvered all day

to avoid the projectiles which were detonating in the water in the tractor area.

On the 20th she moved in to a position 500 yards off Blue

--187--

COAST GUARD MANNED COMBAT TRANSPORT BAYFIELD (APA-33)

--188--

Beach and released five Army DUKW's. They did not come

back to the Line of Departure as planned and the ship waited for them most of

the night. It was later discovered that all the DUKW's had been hit or had

capsized in the heavy surf. The LST then proceeded to launch all of the pontoon

barges. There was a strong offshore wind and two of the barges would not start

and could be towed only by proceeding at one-third speed on one engine. All

barges had to be serviced and by the time the 784 started back to the Line of

Departure she was 22 miles offshore, out with the destroyer pickets. Two barges

started in under their own power and the 784 managed to tow one of the remaining

barges to the Line of Departure but was forced to abandon the other. On the

23rd, two boatloads of Marines were sent in to the beach and next day beached at

"Red One" beach. That night an air raid interrupted unloading. Having finished

unloading on the 25th the LST moored alongside AK-91 to transfer cargo to the

beach. On the 28th, the LST took on post office personnel and equipment and

became "Fleet Post Office, IWO JIMA." This duty continued until 5 March when she

went alongside a merchant vessel to take more cargo to the beach. Air raids

occurred on the first and second of March. On the l5th of March the LST got

underway for Saipan.

LST-760 IS HIT

During the first three days of the assault on Iwo Jima,

the Coast Guard manned LST-760 remained in the LST area, save for one

night of retirement and several runs close to the beach to launch and retrieve

DUKW's manned by reconnaissance parties. In the midafternoon of "D" plus three,

the LST landed on Green Beach, a littered waste of black, volcanic ash at the

foot of Mt. Suribachi. Unloading continued for two days. During the first night,

sixteen casualties, an overflow from a nearby crowded field hospital unit, were

taken aboard and treated by the ships pharmacists' mates, Occasional mortar

shells burst on the beach close to the bow. On the morning of the 23rd, those on

deck watched the scaling of Suribachi and the raising of the first American flag

on its summit. During midmorning of the 25th the ship received its only serious

hit, a heavy mortar shell which crashed on the main deck forward, scattering

shrapnel and wounding two men in the compartment beneath. That afternoon the LST

joined a convoy bound for Saipan.

BAYFIELD TAKES ABOARD CASUALTIES

It was the doctors and pharmacists' mates who had

probably the toughest job aboard the Bayfield. They took aboard

between 250 and 300 Marine casualties. They began coming aboard at night,

brought to the ship on the small amphibious craft from the beach 2,000 yards

away. Then they were transferred to the transport's landing boats and hoisted up

to the deck in them. Some of the wounded, who were able to stand, clutched the

gunwales. Others lay on stretchers on the floor boards. Blood-soaked bandages

covered hands and arms and feet and legs and faces and showed through ragged

holes in the dirt-caked uniforms. In the background was the incessant pounding

of the artillery, the burst of mortar shells and rockets, the chattering of

machine guns, and the crack of rifles. One by one they were gently helped and

carried from the landing boats to the deck of the transport then taken below to

the tiered bunks in sick bay and the crew's quarters.

--189--

THE COAST GUARD COMBAT CUTTER SPENCER

--190--

Here in the

cramped, overcrowded compartments the ship's medical staff went to work.

Pharmacists' mates went quietly from bunk to bunk with hypos and morphine.

Bottles of whole blood and blood plasma hung from over-head pipes. In the ship's

tiny operating room the powerful lights were focused on the bare abdomen of a

young Marine. Three surgeons in white gowns and masks and rubber gloves bent

over the boy deftly removing jagged pieces of shrapnel. Just outside the

operating room, other men lay on blood-soaked stretchers waiting for surgery. At

the end of the corridor was another compartment packed with the less seriously

wounded: minor shrapnel and bullet wounds and concussion and shock cases, men

who seemed to be physically whole but who had fought day after day until they

had reached a point of physical and nervous exhaustion. One of the men in the

first row of bunks was the only survivor of an entire platoon. In the next

compartment, one man already had died and others were dying.

--191--

Table of Contents

Previous Part (23) **

Next Part (25)