Part V

The Marshalls: The Full Range of Use

The capture of the Gilberts accomplished the seizure of airfields

which permitted long-range air reconnaissance against the Marshalls.

Three airfields were in operation immediately after the capture of the

Gilberts and aerial photos provided badly needed intelligence for staffs

who had started planning the conquest of the Marshalls even before the

capture of Tarawa. The Marshalls were mandated to Japan after the defeat

of Germany in World War I and represented the first penetration of the

inner defenses of Japan in the Pacific. The attack of these islands was

expected to be as difficult as that of Tarawa, but the lessons of Betio

were available and it was assumed the same mistakes were not to be

repeated.

The Marshall Islands occupy a vast stretch of ocean and include the

worlds largest coral atoll, Kwajalein, which encloses 655 square miles

in its lagoon. This group of islands also contained a larger number of

major Japanese bases than had been faced in the Gilbert attack. To

prevent the Japanese from concentrating against a single United States

operation from their bases in the Marshalls which included Mule, Maloelap,

Wotje, Jaluit, and Eniwetok Atolls--many of which had airfields, plans

were developed calling for simultaneous landings at Kwajalein and Majuro

atolls. The Majuro Atoll was selected as a target due to its light

defenses and the excellent anchorage it would afford the fleet for later

--102--

Map 6. Marshall Islands.

--103--

staging against the Marianas. Kwajelein Atoll would also be a future

fleet anchorage and contained principal airfields at the islands of

Roi-Namur and Kwajalein. The other major bases in the Marshalls were

to be neutralized by heavy air raids prior to and during the landing

operations.1

The Joint Chiefs of Staff designated the 4th Marine Division, in

training in the United States at Camp Pendleton, California, the experienced

7th Infantry, which had landed in the Aleutians, and the 22d

Marine Regiment, then on duty in Samoa, as the landing forces for the

Marshalls Campaign under overall command of Major General Holland M.

Smith, USMC. Another reinforced regiment, the 106th Regimental Combat

Team (RCT) was added from the 27th Infantry Division as the final plans

for the assault on the Marshalls took shape. The Joint Chiefs exerted

pressure to strike at the earliest moment and after several delays to

allow more training and ship repair, fixed 31 January 1944 as the latest

that the operation could be executed. This early date put considerable

pressure on the green 4th Marine Division, still in the San Diego area,

to complete its training, rehearsals, and organization in time to embark

and sail for a rendezvous at the Marshalls. Division exercises were held

on 14-15 December and 2-3 January 1944 with the last virtually a rehearsal

because this landing included the actual Naval transports which were to

carry them to the target area.2

The Naval group was green as the 4th

Division and this combination of inexperienced forces would produce

unfortunate results later. The 4th DivisIon departed between 6-13

January 1944 without ever having incorporated the final operation orders

into their training or rehearsals.3

The 7th Division, by contrast, was

stationed in the Hawaiian Islands during the planning phase of the

--104--

Marshalls and was able to review and utilize the final operation plans

in their training and final rehearsals between 12 and 17 January 1944.

The 22d Marines was shipped to the Hawaiian Islands for training and

joined the 7th Division in final landings.

The inexperienced 4th Marine Division was assigned to capture the

islands of Roi-Namur and adjacent small islets, while the 7th Infantry

Division was assigned the island of Kwajalein and its surrounding small

Islands. The Majuro Atoll was to be secured by the Fifth (V) Amphibious

Corps Reconnaissance Company since little or no opposition was expected.

Intelligence showed that Roi-Namur was the headquarters of the 24th

Air Flotilla which controlled air operations in the Marshalls and was

commanded by Vice Admiral Michiyuki Yamada. The garrison was composed

of 1,500 to 2,000 aviation mechanics, ground personnel, and pilots. The

only trained ground combat troops were 300 to 600 members of the 61st

Guard Force and about 1,000 laborers. Kwajalein totaled about 1,750

men from various sources including 1,000 soldiers from the Army's 1st

Amphibious Brigade. 500 men from the Navy's 61st Guard Force, and 250

men from the 4th Special Naval Landing Force. To avoid a repetition of

Tarawa, great pains were taken to determine the accurate hydrographic

characteristics of the target islands and Underwater Demolition Teams,

highly skilled Navy swimmers trained to reconnoiter beaches and destroy

underwater obstacles to amphibious landings, were employed for the first

time with excellent results. All islands were completely surrounded by

coral reefs, as had been the case at Tarawa. The strongest enemy defenses

were oriented towards the sea, so United States landings were to be

executed from within the lagoon.4

The defenses of Roi-Namur included ten pillboxes scattered over the

--105--

Intended landing beaches of the 4th Division housing 7.7 mm machine guns,

Armored Amphibian Tractor Battalion. These units contained almost 350

tractors including LVT(2)s of the cargo type and LVT(A)(1)s of the armored

amphibian type.

Training conducted prior to departure for the Marshalls had not

completely prepared the crews for the coming operation. The root cause

appears to be the rapid build-up in amphibian tractor battalions after

the Tarawa landing which emphasized the utility of the LVT in attacking

across coral reefs. The 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion, prior to taking

delivery of its new LVT(A)(1)s, had furnished one officer and fifty men

to pilot LVT(2)s for the 2d Marine Division at Tarawa. This experienced

cadre became the core for that battalions expansion to four companies,

but the 4th Marine Division's 4th Amphibian Tractor Battalion was split

on 5 December 1943 to form the 10th Amphibian Tractor Battalion composed

of B and C Companies, and both battalions were diluted with recruits to

bring them up to strength. This dilution was continued when yet another

reinforcing tractor unit, Company A of the 11th Amphibian Tractor

Battalion, was formed. In addition to the serious effects of the overall

lack of experienced personnel caused by the expansion, about thirty percent

of the officers had never had duty with troops. Less than thirty

days were available for training the newly formed battalions, but the time

was also needed for embarkation and a myriad of other activities required

to form and then move a heavy equipment battalion such as an LVT battalion.

A partial list of the activities of the newly formed 10th Amtrac Battalion

prior to departure from Camp Pendleton serves as an illustration:

-

Constructing a temporary camp during rainy weather.

-

RequIsition and moving battalion supplies, followed crating for

--106--

embarkation aboard ship--this totaled eighty tons of equipment not

counting the LVTs.

-

Assimilating and training new troops.

-

Collaborating with infantry unit leaders during planning--which

consumed much of the officer's time and was aggravated by changes

in plans.

-

Training of naval boat officers in guiding LVTs to the beach.

-

Armoring both the 4th and the 10th Battalion's LVTs--a task

performed by the 10th Amtrac Battalion.8

The net result was to produce an undertrained LVT organization for an

operation that was tactically more complex than any previous landings

attempted in the Central Pacific.

The detail plans for the capture of the Roi-Namur islands required

preliminary landings from the seaward side of the islands of Mellu and

Ennuebing to the southwest of Roi-Namur to secure the northern pass into

the lagoon. The landing force was then to move inside the lagoon for

Ennugarret Island was to be seized by crossing from Ennumennet Island.

These islands were to be used for artillery positiOns for the next day's

assault. The LVTs were brought into the area by LSTs which were to be

stationed about 3,000 yards off the target islands. The landing troops

would be brought over to the LSTs from transports in LCVPs, then climb

the cargo nets up the side of the LSTs and move down inside where they

would board the tractors. This was a complex plan but was an improvement

over the procedure used at Tarawa involving the tricky business of transferring

troops between the LVT and a bouncing small boat in the open sea.

At the line of departure, General Schmidt, commander of the 4th Marine

Division, planned to organize his waves with new techniques for a powerful

--107--

Map 7. Kwajalein Atoll.

--108--

neutralization of the beach just ahead of the leading waves of LVT(1)s.

Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI), a small craft used to land infantry

directly on beaches from gangways, was modified to mount caliber .50

machine guns, 40 mm and 20 mm guns, and 4.5 inch rockets. These gunboats

would lead the way until about 1,000 yards off the beach, where they were

to halt, fire their rockets, and then continue to support the landing with

their automatic weapons by moving to the flank of the boat lanes. The

LVT(A)(1)s were to pass through the LCIs and open fire with their 37 mm

cannon and three caliber .30 machine guns. They would continue this

surppressing fire right up to the beach. The troop carrying LVT(2)s were

to pass through the LVT(A)(1)s and move to the beach before the defenders

could recover. LVT(A)(1)s were to cease fire as their fires became too

dangerous to the friendly troops. They were then to continue to support

the landing by firing from the flanks of the boat lane or by leading the

troops inland in the role of tanks.9

Supporting arms coordination had improved as a result of a valuable

lesson from Tarawa, both naval gunfire and close air support would key

on the position of the landing craft as they approached the beach rather

than attempt to adhere to a fixed time schedule as at Tarawa. This

flexibility was to be a key factor in the success of the operation when

the LVTs fell behind schedule.

Preliminary softening operations against the Marshalls had commenced

in November with air strikes from carriers in the area, with the heaviest

tonnages dropped after the airfields were completed in the Gilberts.

Land based aircraft was used extensively for neutralization of the

Marshalls until 29 January 1944 when carrier aviation returned to the

Marshalls in support of the landings. Aerial bombing was longer and more

--109--

Figure 22. The Landing Craft Infantry (LCI), modified as a gunboat,

was capable of launching hundreds of 4.5-inch rockets and

later also mounted mortars.

--110--

Map 8. D-Day landings prior to Roi-Namur.

--111--

intense than at Tarawa and specific targets identified through photos

were attacked rather than dropping bombs on "area"

targets.10

Surface ship bombardment of the outlying islands began on D-Oay, 31 January 1944,

during the early morning hours. Bombardment also started at this time

against the islands of Roi-Namur in preparation for the landing on the

morning of February 1.

The first landings against Mellu and Ennuebing Islands were scheduled

at 9:00 A.M. with the first battalion of the 25th Marine Regiment

scheduled as the landing force. The landings on D-Day were to be supported

by the 10th Amtrac Battalion and Company A, 11th Amtrac Battalion.

The 4th Amtrac Battalion was withheld entirely to ensure that there would

be enough tractors to land the 24th Marine Regiment on Roi Island the

next day.11

Fire support for the 0-Day landings was also provided by a

provisional platoon from the 1st Armored Amtrac Battalion. Company B,

10th Amtrac Battalion, was to carry troops into beaches on Mellu and

Ennuebing islands using fifty tractors organized into four platoons.

Each platoon had twelve tractors except the 4th, which had ten. Company

headquarters used four tractors. Within the 1st Platoon of Company B,

six specially modified tractors were included which mounted rocket

launchers for added fire support.12

Problems arose almost from the beginning for the landings at Mellu

and Ennuebing. Due to the inexperience of both the Marines and Naval

personnel, few were present who knew anything about debarkation of LVTs

within the LSTs. The elevators which lowered the LVTs from the upper

"weather" deck to the lower deck, sometimes called the tank deck, were

too small. To position an LVT on the elevator successfully, it had to be

driven up a makeshift ramp at an extreme angle which caused wear on the

--112--

clutch and required skill from the driver, often not

available.13

Despite this, the tractors were eventually unloaded, but problems did not

stop. Once debarked, the tractors were to proceed to transfer areas to

receive troops from LCVPs. This is a repeat of the Tarawa procedure,

which was used only during the first two landings. (Subsequent landings

the following day within the lagoon would bring troops to the LSTs to

load aboard the LVTs.) The tractors entered rough seas whipped by winds

up to twenty miles per hour, seasonal for the Marshalls at that time of

year, which slowed not only their progress to the transfer areas but the

progress of the troops in their LCVPs also. Radios became soaked and

inoperative so that last-minute changes in the detailed landing plans

were received by the tractor company informally from the troops boarding

the tractors.

The line of departure was marked by the anchored destroyer Phelps

which acted as the control vessel for the landings. The Control Officer

aboard the Phelps could see that the original H-Hour of 9:00 A.M would

not be met and signaled first a fifteen-minute and then a few minutes

later an estimated twenty-minute delay before the troops would hit the

beaches. General Schmidt and Admiral Conolly, the Naval Commander, both

aboard the task force flagship, realized that a delay was required and

at 9:03 A.M. signaled for a new H-Hour of 9:30 A.M.14

As this was being

done, the Phelps gave the signal for the waves to cross the line of

departure to allow the troops to start the run to the beach to arrive at

the new H-Hour of 9:30 A.M. The waves were not organized and, as one

LVT platoon commander described it, amounted to ". . . three waves

jockeying around as one headed for Jacob Island (code name for Ennuebing

Island)."15

The waves were preceded by the LCI gunboats and the armored

--113--

amphibians.

Thanks to the lessons of Tarawa, fire support schedules were adjusted

to the position of the waves as they approached the beach. Aerial

observers radioed the progress of the waves and naval gunfire and air

support, informed of the delay, extended their coverages of Mellu and

Ennuebing islands.

The LCIs released their rocket payload with the unholy roar that 4.5

Inch rockets emit when fired and moved to the outside of the boat lanes

for further support. The LVT(A)(1)s passed through the gunboats firing

their 37 mm cannon on the move. The rocket-loaded LVT(2)s were unable

to fire their rockets because assault troops, who were to assist in

firing the rockets, were not qualified and the launching racks, burdened

with the weight of the rockets, were almost all torn from their mountings

as the tractors hit the rough coral reef.16

The LVT(A)(1)s continued to

lead until about 200 yards from the beach where they sheered off and lay

to the outside of the line of the advancing troop tractors. Fire coordination

at this point was tricky since it is desirable to keep cannon

fire on the beach up to the last minute. One troop tractor sustained

minor damage when it was riddled by an LVT(A)(1) that continued to fire

just a little too long.17

The troop carrying tractors hit the beach at

Ennuebing and Mellu at 9:52 A.M. and 10:15 A.M. respectively, meeting

little opposition, and both islands were secured after about one hour's

fighting. A total of thirty enemy dead was counted between the two

islands.18

Artillery landed immediately following the seizure of the

islands, carried by the tractors of Company A, 11th Amtrac Battalion.

Tractors which had carried the first waves reorganized and assisted in

further transport of troops and supplies to Mellu and Ennuebing.

--114--

The scene of action shifted rapidly to inside the lagoon for landings

against the islands of Obella, Ennubirr, and Ennumennet islands, all of

which were to be secured by the end of D-Day for artillery positions to

support the main landings the following day. The Second and Third

Battalions of the 25th Marines were scheduled as the landing force,

although only the 2nd Battalion was to be carried by LVTs of Company C,

10th Amtrac Battalion, still aboard the LSTs. There were not enough LVTs

to boat units at Obella and Ennumennet and these landings were conducted

with LCVPs. Tractors were discharged from their LSTs west of Mellu

Island and waited for Mellu and Ennuebing to be secured. These LVTs then

received troops from LCVPs and moved through the passage south of

Ennuebing to the line of departure for Ennubirr Island. Some loss of

control occurred as Company C's radio malfunctioned when soaked by the

spray from the sea's heavy swells. The primary control vessel, the

destroyer Phelps, due to a Navy decision, reverted to fire support and

thus left control to a secondary control vessel equipped with the plans

and radios for the job. However, this vessel was not aware of the change

in plans and failed to assume control, leaving the Assistant Division

Commander, General Underhill, embarked in a small sub-chaser, holding the

proverbial bag. The first he knew of the situation was when the Phelps

swung by and announced by bull horn, "Am going to support minesweepers.

Take Over!"19

By aggressive action and with the aid of the Naval Boat

Control Officers and personnel of the infantry battalions making the

landings, control was restored. The loss of control caused a delay in

the planned hour for landing from 11:30 A.M. to 2:30 P.M. This also

could not be met and a further delay to 3:00 P.M. was authorized by

Admiral Conolly. The Phelps, free of her duties as fire support for the

--115--

minesweepers, returned to her duties as control ship and took station on

the new line of departure for the afternoon assaults. During the time

that was consumed in gaining control of the situation and forming waves,

additional LVTs were procured for the transport of 11/2 waves of the

Third Battalion (500 men) against Ennumennet Island.20

The waves finally

crossed the line of departure about 2:32 P.M., led by LCI gunboats and

armored amtracs of Company D, 1st Armored Amtrac Battalion. During the

delay, bombardment by both air and naval gunfire was prolonged and coordinated

to coincide with the progress of the LVTs. At 2:46 P.M. the

LCI's released their deadly cargo of rockets against both islands and the

LVT(A)(1)s pushed through, firing their cannons on the move. Three minutes

later the fire support ships, Haraden and Porterfield, augmented by the

Phelps, lifted fire to allow final strafing by aircraft as the LVTs neared

the beach. Three hundred yards offshore, the armored amphibians parted,

and the troop carrying tractors passed through to the beach, landing

between 3:12 P.M. and 3:15 P.M. Both islands were secured rapidly by the

two attacking battalions (1000 men) with 24 Japanese defenders killed on

Ennubirr Island and ten defenders killed on Ennumennet.21

Company A, 11th Amtrac Battalion immediately commenced landing the

75 mm pack howitzers of the 14th Marines and first elements finally

reached Ennubirr at about 6:00 P.M.22

This phase of the operation was

difficult because the long trip through the Ennuebing pass and across the

lagoon severely depleted the gasoline remaining in the tractors, thus

restricting the amount of ammunition the tractors could haul to the various

artillery sites and causing a net ammunition shortage. Arrangements had

been made to station refuel ("bowser") boats near the landing beaches of

Ennubirr and Ennumennet islands, but none materialized so tractors of this

--116--

unit were forced to spend the night on the islands for lack of fuel.

At this point an error in coordination occurred when plans were

changed to include an assault against Ennugarret Island, immediately north

of Ennumennet. This island is closest to Namur and would be a valuable

artillery and direct fire weapons site for later support of the main

landings. Plans changed shortly before D-Day called for a landing at

4:00 P.M. but the late seizure of Ennumennet made this time impossible. A

hurried conference was held between the 25th Marines regimental commander,

Colonel Samuel Cummings, and Lieutenant Colonel Justice Chambers, the

battalion commander of 2nd Battalion, 25th Marines, which had just taken

Ennumennet. Colonel Chambers' amtracs were ordered elsewhere after taking

Ennumennet except the two which carried his headquarters section because

the 10th Amtrac Battalion, which was controlling amtrac allocation, did.

not receive the late change in plans.23

The tractors had been reassigned

to search for fuel since the Navy bowser boats which were to be stationed

near the beaches of Ennumennet Island for refuel could not be located.

Daylight was waning, but fortunately two more LVTs were procured while

operating on an artillery mission. Colonel Chambers jammed 120 officers

and men into and on top of the four amtracs and formed a tiny first wave

to attack Ennugarret Island. He waited until 6:00 P.M., the most favorable

tide, and launched them after a preliminary bombardment of mortars

and 75 mm guns firing from half-track cars positioned on Ennumennet

Island. Additional personnel were brought by these same four amtracs in

a shuttle.24

The first wave usage represents one of the heaviest personnel

overloads (normal load is 20-25 Marines per amtrac) ever attempted

for an assault landing. Fortunately, resistance was light, and the

island was secured rapidly.

--117--

Figure 23. The Landing Craft, Vehicle, Personnel (LCVP). This craft,

derived from boats designed for trappers and oil drillers

of the lower Mississippi by Andrew Higgins, was the standard

landing craft of all theaters of World War II and remains

little changed to this day.

--118--

Ennugarret Island was secured about 7:15 P.M. and completed the tasks

of the 4th Marine Division on D-Day, 31 January. At the end of the day,

however, the dispersed operations of the 10th Amtrac Battalion and

Company A of the 11th Amtracs had scattered the LVTs over a wide area.

This was anticipated to some extent and plans called for reorganization

of Company B at Ennuebing Island and Company C on Mellu during the late

evening.25

Company A, 11th Amtracs, partly because of lack of fuel and

partly due to orders from the Navy Beachmaster (the Navy component of

Marine Corps' Shore Party) also spent most of the night on Ennuebing

Island.26

Orders for the next day required the 10th Amtrac Battalion to

lift the 24th Marine Regiment against Namur Island. To accomplish this,

original plans called for the LVTs to reboard their "mother" LSTs for

refueling, greasing, and crew rest. Plans called for the LSTs to mark

themselves with distinguishing light patterns so that tractors returning

to them during hours of darkness could find their way. This was not done

for unexplained reasons. It appears, however, that the inexperienced

crews of the LSTs feared Japanese fire if they displayed lights and failed

to appreciate the total loss of direction that can overcome individuals

during night operations. The result of this failure was to cause numerous

tractors to lose their way in vain attempts to locate their LSTs while

darkness closed on Kwajalein Atoll. As they wandered about, some sought

shelter on nearby islands including Ennumennet Island and ten were lost by

sinking when they ran out of gas at sea.27

[The LVT(2) was equipped with

a bilge pump dependent on the main engine for power and when the vehicles

ran out of gas, the bilge pumps ceased to function and the tractors filled

with water from the many holes caused by scraping over coral during the

day's landings.] The number lost is approximate because seven tractors

--119--

were listed as "probably sunk" at the end of the operation although their

fate was not specifically known.28

Directly related to this disastrous

evolution was the reluctance of LST captains to take LVTs aboard which

did not belong to them because gasoline was limited and skippers feared

they would exhaust their supplies before their assigned LVTs appeared.

The relationship between the LVT crews and the ship's crews of the

various LSTs also was not the best. Inexperience on both sides caused a

build-up of tensions due to the Navy crews lacking indoctrination in the

basic reason for their existence to transport troops, and the Marines

failing in some of their essential housekeeping chores.29

Thus when

Marines were in difficulty during the night of 31 January-1 February,

there was less than full motivation on the part of the Navy to assist them.

As dawn approached on 1 February, the situation facing the 10th

Amtrac Battalion was poor with respect to its mission for the day--lifting

the 24th Marines against Namur Island with an assigned H-Hour of

10:00 A.M. Only a portion of its tractors had returned to their parent

LSTs for refueling and maintenance with the remainder low on fuel and

scattered between Mellu, Ennuebing, and Ennumennet islands. Communications

remained poor because radios once soaked dried slowly, if at all. LSTs

were ordered to discharge LVTs inside the lagoon to lessen the distance

the tractors would have to travel to the line of departure, and troops

were to be brought to the LSTs for transfer to the amphibians rather than

the difficult transfer between the small LCVPs and the tractors. The

movement of the LSTs into the lagoon created the first increment of delay

since many had wandered as far as forty miles away from the atoll during

the night's operations and took too much time to return to meet

H-Hour.30

--120--

Further delay was required in order to procure sufficient tractors to

carry the 24th Marines. Major Victor J. Croizat, Battalion Commander

of the 10th Amtrac Battalion, notified Admiral Conolly during the early

morning hours of the shortage of tractors for the morning landing. A

replacement plan was devised which ordered the tractors of Company A,

11th Amtracs, assigned in support of the division's artillery, to report

to the line of departure to assist in the transport of troops. This plan

was not quickly successful and at 6:30 A.M. Colonel Franklin A. Hart,

Regimental Commander of the 24th Marines, reported to General Schmidt

that he was forty-eight tractors short of the 110 assigned for the

landing on Namur.31

The search for tractors intensified during the next

two hours, but few additional tractors were found. Tractors of Company A,

11th Amtracs, were low on gas and required time to refuel before they

could be loaded with troops. With these accumulating problems, the time

of attack was delayed at 8:53 A.M. to a new H-Hour of

11:00 A.M.32

Bombardment was prolonged to cover the considerable delay.

As the time approached to start the thirty-three minute run from the

line of departure to the beach for an 11:00 A.M. landing, Colonel Hart

was convinced his regiment was not yet ready. He requested another postponement

and received word that W-Hour (H-Hour at Namur) would be delayed

"until the combat team could make an orderly attack."33

This message

gave Colonel Hart the impression that timing was still flexible enough to

allow him to fully organize and he set about getting his waves in final

order. The new landing hour of 11:00 A.M. came and went without Colonel

Hart feeling ready. However, Admiral Conolly was being pressured to

launch the attack by several factors. Hydrographic conditions were

favorable for an attack around the 11:00 A.M. hour, there was concern

--121--

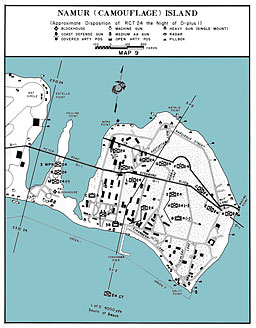

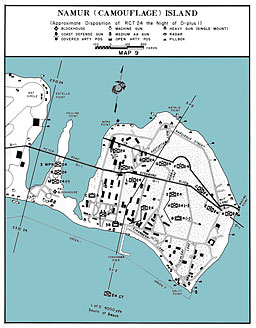

Map 9. Capture of Namur

--122--

that the landing should not be delayed so that the neutralizing effects

of the intensive preliminary bombardment would be dissipated, and

tractors idling at the line of departure were consuming scarce gasoline.

At 11:12 A.M. Admiral Conolly ordered the Phelps to drop the signal flag

on her yardarm and thus the signal for crossing the line of departure was

given. It caught Colonel Hart by surprise and his regiment was still not

ready to make an organized assault. The landing on Namur Island resembled

more of a ferry operation than a powerful assault but Admiral Conolly had

correctly counted on the devastating effects of the aerial and naval

bombardment to carry the landing.

Meanwhile, the situation that faced the 4th Amtrac Battalion and the

landings on Roi was a contrast to the hectic morning of the 10th Battalion

on Namur. The 4th had been withheld from D-Day landings to insure an

adequate supply of tractors for the 23rd Marines for the landings on Roi,

and although all tractors were on hand, the 4th Amtrac Battalion still

experienced some of the same problems firing the initial unloading of

their tractors from LSTs that had previously plagued the 10th Battalion

on D-Day. Tractors loaded on the weather (upper) deck of the LSTs had to

be driven up a steep ramp on the elevator in order to clear for lowering

to the tank (lower) deck. At one point, to obtain clearance, crews on

one LST were forced to use welding gear to cut off the tips of fenders of

the vehicles prior to lower them.34

Although this process delayed the

4th, the assault of the 23rd Marines was organized in time to meet the

11:00 A.M. H-Hour. The landing force was ready for landing long before

the 24th Marines and impatiently waited as the H-Hour passed without any

signal from the Phelps which was controlling landings on both Roi and

Namur. Control was weakened within the 4th Battalion due to wet,

--123--

inoperative radios, but the improved performance of Navy guide boats

over the previous day overcame this weakness and when the signal came

from the Phelps, the crossing of the line of departure proceeded in

good order.

The attack on Roi was powerfully reinforced. In addition to the 4th

Amtrac Battalion, the 23rd Marines were preceded by five rocket-firing

LCI gunboats, thirty LVT(A)(1)s of Companies A and C, 1st Armored Amphibian

Battalion, and twelve LVTs of the 4th Amtrac Battalion equipped with

rockets.35

The LCIs released their rockets 1,000 yards off the beach and

cleared to either side to provide further support with their 40 m cannon

and machine guns. The LVT(A)(1)s of the 1st Armored Amphibian Battalion

passed through and commenced firing their 37 m cannon and machine guns.

The rocket-firing LVT(2)s fired their rockets successfully, but they fell

short, landing around the LVT(A)(1)s proceeding ahead of them. Incredibly

there was no damage and the armored amtracs continued towards shore. The

armored amtracs were particularly heavily concentrated in front of the

right half of the beach with eighteen of the thirty vehicles attached to

the 2nd Battalion, 23rd MarInes, landing in that zone.36

The armored

amphibian wave had a tendency to narrow and widen its width in an

accordion fashion, particularly after they got near the beach and the

drivers closed their protective hatches. The reduced visibility through

periscopes caused some tractors to collide, but they managed to maintain

fair alignment as they hit the beach.37

At Roi, the armored amtracs did

not stand off the beach but preceded the troops inland. The attack hit

with a great deal of momentum and the advance across Roi was so fast that

it became disorganized. Tanks that had raced ahead had to be called back

In order to get a coordinated attack to sweep the island.38

During the

--124--

Map 10. Capture of Roi

--125--

forward motion of the attack, the armored amphibians protected the right

flank of the attack moving along the beaches. with some armored amtracs

in the water and some out, shooting at dugouts and sending the Japanese

scurrying. The island was secured by the end of the day.

Back at Namur, the disorganized start of the ship to shore movement

of the 24th Marines carried to the beach. The armored amphibians of

Companies B and D, 1st Armored Amtrac Battalion, approached the beach

under orders from the regimental commander to precede the troops to

positions one-hundred yards inland, but they did not execute the order.

About two-hundred yards from shore, they stopped and attempted to support

the landing in place and allowed the troop carrying tractors to pass.

The halt of the LVT(A)(1)s caused confusion, but the LVT(2)s managed to

pass through, even though the armored amtracs continued to fire both

their 37 mm cannons and machine guns after the LVT(2)s were in front of

them.39

This was a dangerous practice created by inexperience coupled

with a greater amount of rubble on the Namur beaches and the presence of

an anti-tank ditch just inland of the beaches which stopped a number of

LVTs.40

The 24th Marines met greater resistance as they attacked, due to

the greater number of buildings and storage bunkers providing cover to

the enemy and thick underbrush which gave the defenders further concealment.

The 24th Marines' attack did not have the momentum of the attack

on Roi due to the rough beach and the disorganized condition of their

landing waves and the net result was congestion on the beaches involving

troops, LVTs, and later light tanks that tried to come ashore to reinforce.

The heavier construction of the few plilboxes and fortifications

that survived naval gunfire was unaffected by the 37 mm cannon fire of the

armored amtracs or the light tanks, which mounted the same 37 mm guns, and

--126--

so the Regimental Commander relied on the 75 mm guns of his supporting

armor half-tracks.41

Despite the handicaps at the beachhead, the attack

moved inland close to the scheduled pace, but suffered a major disruption

at 1:05 P.M. when Marines attacking a storage bunker ignited a large

cache of Japanese torpedo warheads. The ensuing explosion covered the

entire island in a thick pall of smoke that convinced some Marines of a

gas attack; many panicked looking for discarded gas masks.42

Two more

blasts followed detonated by Japanese to capitalize on the confusion.

The three blasts, which caused chunks of concrete to become deadly missiles

and tree trunks to fly through the air like toothpicks, accounted

for about half of the 24th Marines' total casualties during the attack

on Namur. The first blast was the biggest and accounted for twenty

killed and one hundred wounded, most from Company F, 24th Marines, the

attackers of the bunker.43

As the problems of the attackers on Namur

became known, support began to arrive. The company of medium tanks

operating on Roi was switched to Namur over the connecting causeway and

participated in the later advances as the spearheads. Light tanks and

armored amtracs were also used, but their light guns were not decisive

against many of the fortifications on the island and their chief service

appears to have been firing cannister rounds to shred foliage or against

personnel caught in the open.44

Hard fighting continued throughout the

afternoon and into the morning of 2 February. The island was finally

secured at 2:18 P.M., 2 February 1944.45

Use of the LVT(2)s after the attacks on Roi and Namur was light.

Logistical considerations for an attack on a small island are minimal

and so was the use of the tractors of the 4th and 10th Battalions. The

battalion command post of the 10th Amtrac Battalion was established on

--127--

Ennubirr Island on 1 February, and most of the 10th Battalion's tractors

reorganized on that island after landing the waves at Namur. Maintenance

and salvage operations were conducted for the remainder period

in northern Kwajalein Atoll, although some tractors were used to clear

tiny islands to the south of the target area between 2 through 5 February.

No further difficulties were encountered.

While the Marines were assaulting the northern portion of the

Kwajalein Atoll, the United States Army's 7th Infantry Division was

attacking the southern end using the same overall approach of first

securing the outlying islands for security and artillery positions,

followed by a main attack on 1 February against the big island of

Kwajalein. The Army Division had less than half the number of LVTs the

Marines had. The 708th Provisional Amphibian Tractor Battalion was

divided into four groups, Able, Baker, Charlie, and Dog, each with thirty-four

tractors. Groups Able and Dog had participated in the D-Day landings

against the outlying island and groups Baker and Charlie were

fresh.46

This parallels the Marines' use of the 10th Amtrac Battalion on D-Day and

holding the 4th Amtrac Battalion fresh for the main landings the following

day. The tractors used by the Army were forty-six LVT(2)s and fifty-six

LVT(A)(2)s which the Army had requested as a modification of the unarmored

LVT(2).47

The armored version of the LVT(2) used by the Army suffered

from reduced cargo carrying capacity because of the permanent attachment

of its armor plate, but it was a tougher machine against enemy fire, and

resistance was expected to be heavy. In addition to the LVT(A)(2)s of the

708th Provisional Amphibian Tractor Battalion, Company A of the 708th

Amphibian Tank Battalion would precede the main landings with their

seventeen LVT(A)(1)s. The Army supplemented the cargo capacity of its

--128--

amphibians with the addition of one-hundred newly developed amphibious

trucks, the two-and-one-half ton DUKW. This was to be one of the Army's

greatest contributions to amphibious equipment and it became a workhorse

during the remainder of the war. Sixty of these vehicles were assigned

to transport artillery and forty were preloaded with emergency supplies

to be used as floating dumps, available for instant dispatch to the

beach as the situation required.48

The vehicle was designed around the

standard two-and-one-half truck chassis as a cargo carrier and therefore

was not armored.

The 7th Infantry Division had been stationed in Hawaii near the planning

center at Admiral Nimitz's Pearl Harbor headquarters and was therefore

able to incorporate fully the latest schedules and tactical measures

into its final rehearsals. The advantage of this was clear on 1 February

as the 7th Division executed a smooth landing against the main island of

Kwajalein. The only problem appeared to be the tendency of the LVT(A)(2)

to veer to the left, which caused drivers to overcompensate to the right,

bunching waves in the right portion of their boat lanes. Rather than

precede the leading waves, as at Roi-Namur, the Army stationed their

armored amphibians on each flank of the leading wave, with the LVT(A)(1)s

angled towards the beach at about forty-five degrees. From overhead,

this formation, including the troop-carrying LVTs, looked something like

a large "V".49

This formation allowed the leading troop LVTs to use

their machine gun power along with the firepower of the armored amtracs

and cleared the armored amtracs from the path of the troop LVTs as they

hit the beach. Thus, the confusion that occurred at Namur was avoided.

Such an arrangement required a wider frontage for the first wave because

the armored amtracs extended off each side of the first wave. It was

--129--

successful at Kwajalein due to the relatively generous amounts of usable

beach for the assault, equipped as it was with amtracs.

Preliminary bombardment by ships and air had been thorough, and

little immediate resistance was encountered by the troops of the 7th

Division as they landed on schedule at 9:30 A.M. An observer commented

that the island "looked as if it had been picked up to 20,000 feet and

then dropped."50

The armor available was later increased with M-10 tank

destroyers, which were a tank-like vehicles with an open turret mounting

a powerful three-inch gun. With this amount of armor, with large guns

already available, the armored amtrac was not to play a role in the

fighting on Kwajalein. LVT(A)(2)s and the DUKWs acted in logistical support

of the operation as the infantrymen fought the length of the island.

It took the 7th Division four days to secure the island in fighting

characterized by excellent Army tank-infantry coordination. The Japanese

tended to infiltrate Army positions successfully at night, causing confusion

and firing in all directions, but these incidents occurred in small

numbers and did not significantly hinder the progress of the battalions.

The buildings and fortifications on Kwajalein resembled those found on

Roi-Namur although many of the heavy concrete structures were clearly

designed for protective storage rather than for combat use.51

With the seizure of Kwajalein, the first phase of the conquest of the

Marshalls was complete. It had been far quicker and cheaper than anyone

had dared dream based on the intelligence gathered and the grim memories

of Tarawa. The 4th Marine Division lost 313 killed and 502 wounded while

the 7th Division lost 173 kIlled and 793 wounded.52

The Kwajalein Atoll

had been seized with greater speed than anticipated and General Holland

Smith and Admirals Spruance and Turner all felt that a speed-up in the

--130--

timetable for the complete conquest of the Marshalls--the attack on

Eniwetok--was in order.

Admiral Nimitz had planned the capture of the Eniwetok Atoll during

the early preparation for the seizure of the Marshalls. During January

1944, the 2nd Marine Division and the 27th Infantry Division, United

States Army, were designated the landing forces for the atoll which lay

in the western reaches of the Marshall group, 326 nautical miles from

Roi-Namur. The lagoon measures twenty-one miles in length and seventeen

miles in width with ample space for a major fleet anchorage. The three

islands within the atoll were Engebi, Parry, and Eniwetok, all principal

bases. None of the islands were large, varying only from one to two

miles in length with widths from one mile to six-hundred yards. Engebi

Island contained the atoll's only airfield, completed in July 1943, which

occupied almost all of the island's area. Intelligence gathered prior to

the departure of the task force from Hawaii for the Marshalls was limited

to a few overhead photos. Material captured during the attacks on

Kwajalein Atoll included a detailed hydrographic chart of the Eniwetok

Atoll which greatly assisted in attack planning. Photo coverage was

gradually expanded during January 1944, and the enemy force in Eniwetok

was estimated from this source to be from 2,900 to 4,000 men. This force

was constituted mainly from the 1st Amphibious Brigade which arrived in

the area on 4 January 1944, to garrison the atoll and erect fortifications.

The brigade was 3,940 men strong and General Yoshima Nashida, its

commander, distributed his strength among the three principal islands on

the atoll, Parry, Eniwetok, and Engebi, with brigade headquarters on

Parry Island. The force sent to Engebi numbered 736 from the brigade,

some aviation, civilian, and labor personnel, and totaled about 1,200 men.

--131--

Map 11. Eniwetok Atoll

--132--

General Nishida maintaIned 1,115 brIgade men to defend Parry and his

headquarters, and Eniwetok had about 908 brigade soldiers. Defenses

were trenches, dugouts, log barricades at the beaches, and "spider traps"

consisting of fighting holes interconnected with oil-drum tunnels dug

Into the earth. Each hole was covered with a sand cover, palm frond, or

ordinary piece of metal. It allowed a sniper to pop up, fire, and disappear

from sight, and if necessary to abandon his hole via the

tunnels.53

The Japanese approach, as it had been at other atolls, was to attempt to

destroy the landing force at the beach by fire and counterattack.

The reserves designated for the Kwajalein landings were immediately

available against the Japanese forces at Eniwetok Atoll. They consisted

of the 22nd Marine Regiment and the 106th Regimental Combat Team from

the 27th Infantry Division. With the Japanese split among three islands,

the available forces numberIng 10,000 assault troops were sufficient to

achieve superiority at each island. Because forces were immediately

available in the Marshalls area, the, timetable for attack against Eniwetok

was radically accelerated. Previous dates considered for the attack had

been in the March-May 1944 period. The new date set for the landings was

15 February, but this was ultimately shifted to 17 February to allow

additional time for carrier strikes against the Japanese bastion in the

area, Truk Naval Base, 669 miles southwest of Eniwetok. Truk was a major

staging area, repair facility, and naval and air base, which would require

neutralization to conduct unmolested landings at Eniwetok.

With Kwajalein secured only on 5 February, little time remained for

planning. The Eniwetok plans resembled those executed against Kwajalein.

Three outlying islands would be seized on D-Day, 17 February, for use as

artillery positions to support the landings the next day by the 22nd

--133--

Marines on Engebi. After seizure of Engebi, when it became clear that

the reserves designated for use in that landing would not be needed,

landings would be conducted by the 106th Regimental Combat Team against

Eniwetok and two hours later against Parry Island. Aerial photos assured

intelligence analysts that most of the atoll's defenders were concentrated

on Engebi with smaller detachments on Parry and Eniwetok.54

From this

conclusion came the decision to use the more highly trained 22nd Marines

against Engebi and the less experienced Army unit, supported by one

battalion of the 22nd Marines, against Parry and Eniwetok.

Although preliminary naval gunfire support and air strikes were not

as heavy as those against the Kwajalein Atoll, they wreaked havoc among

the defenders. One prisoner of war estimated that fully half the

defenders of Eniwetok were killed by the naval gunfire and air strikes

that hit the atoll during 17 and 18 February, from cruisers, destroyers,

and aircraft.55

There was a heavy air strike against Truk simultaneously

with the landings and the airfield at Engebi had been heavily damaged by

carrier raids on 30 January and again on 10-12 February. The few defenses

which the Japanese had been able to construct during the six weeks prior

to the American landings suffered heavily from the efficient and effective

preliminary fires. The sole American weakness was the failure to use

heavier bombs against Eniwetok, which had the highest elevation--up to

twenty feet above sea level, and thus yielded the Japanese more earth in

which to bury their spider traps and resist air attack.56

Nevertheless,

the atoll's defenders were near starvation when the United States Navy

finally and boldly steamed into the lagoon of Eniwetok Atoll through the

narrow deep passage in the southern end of the atoll.57

The landings were to be supported by the 708th Provisional Amphibian

--134--

Tractor Battalion, minus one group remaining at Kwajalein Atoll. This

support totaled forty-six LVT(2)s and fifty-six LVT(A)(2)s, plus seventeen

LVT(A)(1)s of Company A, 708th Amphibian Tank Battalion.58

The latter was

the team that had performed so well during the Kwajalein Island landings

of the 7th Infantry Division. About ten tractors were used during the

preliminary landings on 0-Day, 17 February, thus leaving the bulk of the

battalion rested and fully ready for the landings against Engebi and

Eniwetok on 18 February.

The LVTs for the Eniwetok landings were carried to the atoll in LSTs,

but in contrast to the Navy-Marine cooperation problems at Roi-Namur,

Navy-Army cooperation between the LSTs and the 708th Amphibian Tractor

Battalion was excellent. Histories do not offer explanations for this,

but it appears probable that the traumatic experiences of the LVT crews

during the assault on Roi-Namur developed some lessons on cooperation

which the LST crews at Eniwetok understood and took action to implement.

The LSTs stationed themselves within one-thousand yards of the line of

departure and thus reduced the run required by the LVTs.59

Because the

operation was staged from within the lagoon, eliminating the rough

passage at sea experienced by LVTs at Roi-Namur, radios stayed drier and

schedules were met.

The Engebi H-Hour was set at 8:45 A.M. Preliminary landings the day

before had been successful and artillery would join the naval gunfire

bombarding the island as the LVTs approached the beaches. Cruisers were

to cease fire when the LVTs were within one-thousand yards of the beaches,

but destroyers were instructed to keep firing with their five-inch guns

until the LVTs were three-hundred yards from the beach.60

The Engebi

ship-to-shore movement was power laden. Six LCI gunboats preceded the

--135--

LVTs and armored amtracs to fire their rockets and automatic fire. Next

came the leading five waves of LVTs carrying troops. Each wave consisted

of eight to ten tractors for each of the two battalions, the 1st and 2nd

battalions of the 22nd Marines, making the landing against

Engebi.61

Five LVT(A)(1)s were echeloned on the outside flanks of the leading troop

LVT wave, and the remaining seven were a "V" shape between the two

battalion formations of LVTs, with the open end of the "V" pointing

towards the beach.62

This formation thus produced an integrated troop

carrying and LVT(A)(1) formation, similar to that used against Kwajalein

Island by the Army.

The troop transfer proceeded smoothly using the same methods employed

at Kwajalein Atoll. The Amtrac Battalion Commander was directed to take

position in the control vessel at the line of departure and after the LVTs

landed, they were to report to him for further orders. LVTs were preloaded

with water and ammunition to permit a fast build-up of supplies at

the beach. The LVTs crossed the line of departure at 8:15 A.M. LCI gunboats

released their rockets and veered away, but the rockets fell short.

At 8:43 A.M., two minutes ahead of schedule, the LVTs hit the beach

against light resistance. Although scheduled to proceed inland for about

one hundred yards for fast penetration and to provide fire support with

their machine guns, LVTs were forced to stop on the beaches by the rubble

of coconut tree logs and other material churned up by the preliminary

bombardment. This initially created some congestion but did not seriously

Impede the landing. Some LVTs of the left zone landed two-hundred yards

too far to the left, but junior officers and non-commissioned officers

quickly reorganized and pressed inland. On the right, one platoon was

late in landing due to mechanical break-down. This platoon belonged to

--136--

Company A, 1st Battalion, 22nd Marines, which held the right flank

sector in the attack across Engebi. Company C of the 1st Battalion was

to attack Skunk Point, to the right rear of A Company, to secure that

point as A Company swept inland. The late platoon hurried into position,

but too late to prevent Japanese flushed by Company C's attack from

penetrating into a widening gap between A and C Companies as A Company's

attack progressed inland. The terrain was tangled undergrowth and it

was necessary to halt the advance of A Company and call on tanks, which

had just landed, to rectify the situation.63

The fighting on Engebi resembled the contrasts that occurred between

Roi and Namur. On the left, the 2nd Battalion moved rapidly through the

open terrain of the airfield on Engebi, and Newt Point at the far end of

the island in the 2nd Battalion's zone was seized at

1:10 P.M.64 It was

not all quick work because the Japanese had entrenched medium tanks with

47 mm guns in this area and they were overcome only with combined

artillery and 75 mm tank fire. On the right, fighting moved more slowly

as Japanese took refuge in the dense undergrowth and staged a last-ditch

fanatical defense. The few pillboxes encountered on Engebi were in this

area as well as many spider traps. The Marines quickly discovered that

by throwing smoke grenades into the passages of the spider web, they

could readily locate the network's terminal fighting holes and seal them

with explosives. In this way, the Marines punched forward supported by

tanks and half-tracks carrying 75 mm guns. LVTs, both armored and cargo,

were not used due to the extreme ruggedness of the terrain and the need

for the heavier gun power of the medium tank, M4, known as the General

Sherman. Because of the devastating effect of the preliminary bombardment,

the island was secured far faster than might have been the case

--137--

with less preparation. Despite the fanatical defense of Japanese in the

1st Battalion's zone, the island was declared secure at 2:50 P.M. by the

Landing Force Commander, Brigadier General Watson.65

Although mopping-up was to continue on Engebi for another day and

a half, it was time to commence the next phase of the Eniwetok Atoll

operation, the attack of Eniwetok Island itself. The 3rd Battalion,

22nd Marines and the 2nd Separate Tank Company with its M4s, was ordered

reembarked for this landing. The 3rd Battalion was the floating reserve

for the landing which was made by the 1st and 3rd Battalions of the

106th Regimental Combat Team (RCT), and the Marine tanks were attached

to the 106th for support.

H-Hour was set at 9:00 A.M. on 19 February for Eniwetok Island.

Because it was believed that this island was more lightly defended than

Engebi, naval gunfire and air strikes had been more harassing than

deliberately destructive in nature. Only 204.6 tons of projectiles were

thrown against Eniwetok Island with none larger than eight-inch, in contrast

to the 1,179.7 tons fired against Engebi.66

H-Hour was delayed

first to 9:15 A.M. and then to 9:22 .A.M. due to fears that the armor,

reembarked from the landings at Engebi, would not arrive on time. The

armor was on time and assault troops were ordered across the line of

departure at 9:09 A.M., with troops hitting the beach at

9:16 A.M.67

Trouble began at once. The LVT(A)(1)s were under orders to proceed

one-hundred yards inland, but were stopped by a log barricade at the

beach. The area was heavily fortified with spider traps and the Army

attack stalled. The Japanese counterattacked around noon with three-hundred

to four-hundred men but the attack was beaten down with some Army

casualties. Despite this success, the Army attack continued forward only

--138--

by inches mainly because many defensive installations survived the

preliminary naval gunfire and in fact most of the spider traps were

untouched due to their greater depth. Against this tough nut, the 106th,

an inexperienced outfit, made very slow progress. A Marine Battalion in

floating reserve was landed at 1:30 P.M. to impart momentum to the

attack and was thrown into the line heading south against the rear of

the island main defenses, fighting alongside the 1st Battalion, 106th

Regimental Combat Team (RCT). The Marine battalion did accelerate the

attack but gaps opened between it and the lagging Army unit, into which

troublesome Japanese infiltrators moved causing some confusion until in

each case they were eliminated. Fighting frequently occurred in dense

underbrush which limited observation and log emplacements were sometimes

not discovered until the attackers were less than thirty-five yards away.

Due to the close proximity, naval gunfire or other heavy caliber support

could not be used and individual action was required by groups of

Infantrymen to silence these defenses.68

Problems were also encountered

In allocation of the tank support and the Regimental Commander, Colonel

Ayers, did not appear willing to release tanks from either the Marine

medium tank company or the Army light tank company to the Marine

battalion despite repeated requests. They remained in support of Army

units who were also having difficulty with the enemy situation. It

required another day, until 2:45 P.M. on 20 February, to secure the

southern end of the island; the northern end was not secured until

2:30 P.M. on 21 February.69

As on Engebi, armored amtracs did not take part. In the combat on the

island because the defenses were too heavy for the vehicles light 37 mm

gun. Cargo carrying LVTs reverted to logistical roles after the landing.

--139--

Map 12: Seizure of Eniwetok Atoll

--140--

The unexpected toughness of the Eniwetok fight forced changes in

plans for the attack on Parry, the last objective. This had been scheduled

for the 106th, but it was clear that to keep a rapid timetable,

it would be necessary to give this mission to the 22nd Marines, the.

victors of Engebi. H-Hour was scheduled for 9:00 A.M. on 21 February,

and both the 1st and 2nd Battalions of the regiment were available in

time for that original H-Hour. Timetables were delayed, however, when

General Watson decided to postpone the landing until the 3rd Battalion,

fighting on Eniwetok, would be available as a floating reserve. The

new time was 9:00 A.M. on 22 February. With the unexpected resistance

rising, preliminary bombardment of Parry was increased and the island

rocked under an intense load of shells including 143 6-inch, 751 14-inch,

896 8-inch, and 9,950 5-inch shells into an area of only

200 acres.70

Another significant change was the decision by General Watson to compress

the frontages originally planned for the landing beaches because he felt

they were too large and in doing so, he also shifted their location

three-hundred yards northward. However, this information was not completely

distributed, and caused problems during the ship-to-shore phase

of the landing.71

Utilization of the LVTs remained the same as previous landings

executed by the 708th AmphibIan Tractor Battalion. The first waves

crossed the line of departure at 8:45 A.M. preceded by LCI gunboats, as

usual. Naval gunfire continued during the early part of the approach

and three LCI gunboats on the right flank were struck by 5-Inch shells

from ships firing on radar because of the smoke. They lost thirteen men

killed, forty-six wounded, but stayed on station and fired their rockets

before leaving the area.72

As the LVTs approached the shore, they were

--141--

guided by Navy guideboats towards the originally planned beaches, three hundred

yards too far south. This drift affected the LCIs and appears

to be the cause of the friendly fire hitting the right flank gunboats.

Buoys to within 500 yards of the beach, along the division between the

two landing teams, were to guide the LVTs, but the wind was carrying the

smoke from the naval gunfire out over the incoming waves and drivers

could not see any of the buoys or landmarks.73

The Marines of the first

wave landed 300 yards too far south, but succeeding waves, lost in the

smoke, landed at varying positions along the beach. This confusion was

corrected, as it had been in the past, by the aggressive leadership of

junior officers and non-commissioned officers. Resistance on the beach

was heavy but companies rapidly pushed through, assisted by the medium

tanks of the 2nd Separate Tank Company. Three Japanese tanks were part

of the defense of Parry and were not entrenched as stationary pillboxes

as on Engebi. For unknown reasons, the Japanese chose to wait until

Marine armor had landed before conducting a tank attack with their three

tanks. (Japanese tanks throughout the war remained flimsy with inferior

gun power by American standards.) The attack was disastrous for the

Japanese, losing all three tanks and crews,with no damage to the General

Shermans of the 2nd Separate Tank Company.74

Tank-infantry coordination

was excellent during the Parry fighting, assisted by the light tank

company of the 106th RCT, and this support led to the rapid elimination

of the defenders of Parry even though many spider traps and trenches had

survived the shelling. Although a narrow strip of land at the southern

end remained contested at nightfall, the Regimental Commander, Colonel

Walker, declared the island secure at 7:30 P.M. on

22 February.75

With this declaration, the final objective of the Eniwetok operation, code

--142--

named CATCHPOLE, was completed.

As in the Kwajalein Atoll, for six weeks after Eniwetok there were

follow-up landings on tiny islets ringing the atoll. The procedure

usually involved a low-level aerial photo run by a PBY flying boat,

which delivered photos to the landing force consisting of an LST

carrying the assault troops and six to nine LVTs. Two LCI gunboats, a

destroyer escort for gunfire support, and a mine sweeper to clear the

approaches to the islets and atolls being visited made up the remainder

of the miniature task force. Resistance varied from none to intense fire

fights where a maximum of eighteen Japanese were killed on one island.

Units of the 22nd Marines performed many of these landings, but a force

of 199 Marines from the 1st Defense Battalion also conducted some

operations during this phase. The last landings were made on 21 April

1944. Only four atolls were by-passed which contained airfields and

sizeable enemy forces: Maloelap, Wotje, Mule, and Jaluit atolls. These

targets were kept neutralized by the 4th Marine Aircraft Wing which began

entering the Marshalls bases at Roi and Engebi during February 1944.

The Marshalls campaign represents a rugged test of the family of

LVTs available at that time because it exploited the full range of LVT

capabilities and was the first extensive use of the armored amphibian

LVT(A)(1) which mounted the 37 mm gun as its main armament--the same gun

as the light tank M5, extensively used by both Army and Marine units.

As far back as Tarawa, however, the 37 mm gun had demonstrated its

inability to destroy many of the substantial Japanese fortifications

commonly encountered in the Pacific. In contrast, the 75 mm gun of the

M4 Medium Tank, the General Sherman, was highly effective and frequently

responsible for destroying pillboxes impeding infantry progress. It was

--143--

clear that the armored LVT needed a heavier gun to become a more valuable

support weapon to the Marine infantry fighting their way inland.

Another point requiring review was the type of gun needed because the

capabilities of the gun would shape the ultimate tactical utilization of

the vehicle. The 37 mm gun was a flat trajectory tank gun which tended

to force the LVT(A)(1) to attempt to assume the role of the tank, an

attempt generally unsuccessful since the overall power of the gun was

Insufficient and the vehicle was frequently blocked from proceeding

inland by beach debris. It appeared that the tank made the best tank

and the gun chosen for the armored LVT should be complimentary to the

tank gun rather than try to duplicate its characteristics.

The LVT(2) and (A)2 were heavily used during the Marshalls and in

many ways stood the test, but problems became obvious. The loss of

many LVT(2)s of the 1Oth Amtrac Battalion at Roi-Namur due to sinking

focused attention on the need for an additional bilge pump for the

incoming water from coral and bullet holes when the vehicle's engine

stopped. Water inside the vehicle also caused considerable trouble with

communications so a better installation of the radios was required to

water proof them. In response to the frequent loss of communications

plaguing LVT operations, Marine tractor crewmen were now required to

learn semaphore signalling which was frequently used to control the LVT

in the water later in the war.76

The desirability of adding a ramp to

the design of the LVT had long been recognized. It was necessary to lift

cargo over the side of the LVT(1) and (2); the incorporation of a ramp

would greatly speed the loading and unloading of cargo as well as make

room for the possible loading and transport of vehicles within the LVT.

Maintenance continued to be a prime consideration in the availability of

--144--

the LVT. The track grousers (cleats) required continual tightening

and wore down rapidly when in contact with the coral or rock. A worn

grouser reduced the speed of the LVT in the water which in turn had a

direct bearing on its ability to execute assault and logistics runs.

The grouser also had a direct bearing on the response and control of the

vehicle in the water--never an outstanding feature of the LVT. As one

former crewman recalled, control in water was like "being in a bathtub

with an oar."77

Despite the technical problems, the tactics evolved for the use of

the LVT in the assault role resembled those standardized for the remainder

of the war. The placement of the LVT(A)(1) in the lead wave or ahead of

the lead wave of troop tractors gave the landing fire power and momentum

right up to the sand. The Army practice of placing the LVT(A)(1)s to each

side of the leading wave simplified the control problem encountered at

Namur when the LVT(A)(1)s were placed directly ahead of the troop carrying

LVTs and endangered friendly troops by firing over their heads with their

tank guns as the troop LVTs passed ahead to make the landing. The use of

rocket firing troop LVTs was only a marginal success, but experimentation

continued with this type of fire support with later models. Roi-Namur

emphasized the need for detailed briefing of the LVT crews on all aspects

of the landings so that beaches would not be missed and the correct

troops were carried ashore. Another refinement needed was a smoother

transfer of troops to the LVTs because the complex business of offloading

troops from their transports and boating them over to LSTs for loading

into LVTs consumed so much time that an 4:30 A.M. reveille was required

for a landing at 9:00 A.M. The rest and feeding of the troops immediately

before they landed was important and two to three hours of riding around

--145--

in LCVPs and LVTs before actually landing was destructive for morale and

troop efficiency.

The Marshalls was atoll warfare. Although it was characterized by an

overwhelming naval gunfire preparation that General Holland M. Smith, the

overall landing force commander, described as "historic", it nevertheless

required the services of the LVT to overcome the ever-present coral reefs

that surrounded every island in the area. The whole Marshalls campaign

was accomplished with a light cost in lives due in no small part to the

continued use of the LVT. General Holland Smith summarized his feelings

on the use of LVTs by stating, "Our amphibian tractor proved effective

but . . . our control and employment of amtracs was capable of

improvement."78

Everyone from engineers at Food Machinery Corporation to Marines

in the field were working on just such improvements so that Operation

GRANITE, the capture of the Marianas, would be swift. The first objective

was a large island called Saipan.

--146--

Table of Contents

Previous Part **

Next Part

Footnotes

1.

Robert D. Heinl and John A. Crown, The Marshalls: Increasing

the Tempo (Washington D.C.: Historical Branch, G-3 Division,

Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, 1954),

p. 13.

2.

Henry I. Shaw, Bernard C. Nalty, and Edwin T. Turnbladh,

Central Pacific Drive, Vol. III of History of United States Marine

Corps Operations in World War II (5 vols.; Washington D.C.: Historical

Branch, G-3 Division, Headquarters, United States Marine Corps, 1966),

p. 135.

3.

Ibid.,

p. 136.

4.

Ibid.,

pp. 140-141.

5.

Ibid.

6.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 44.

7.

Jeter A. Isely and Philip A. Crowl, The United States Marines

and Amphibious War (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1951), p. 262.

8.

10th Amtrac Battalion, Report on Operations of the 10th Amtrac

Battalion During Operation Flintlock (In the Field: 10th Amtrac Battalion,

1944), p. 2.

9.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 128.

10.

Ibid.,

p. 137.

11.

Ibid.,

p. 152.

12.

10th Amtrac Battalion, Report on Operations, Enclosure (a), p. 2.

13.

Ibid., Enclosure (a), p. 8.

14.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 44.

15.

10th Amtrac Battalion, Report on Operations, Enclosure (a), p. 6.

16.

Ibid.

17.

Ibid.

18.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 46.

19.

Ibid.,

p. 48.

20.

Ibid.,

p. 49.

21.

Ibid.,

p. 50.

22.

10th Amtrac Battalion, Report on Operations, Enclosure (c), p. 3.

23.

Ibid., Enclosure (a), p. 1.

24.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

pp. 51-52.

25.

10th Amtrac Battalion, Report on Operations, Enclosure (a), p. 7.

26.

Ibid., Enclosure (c) pp. 3-5.

27.

Ibid., Enclosure (d), p. 2.

28.

Ibid.

29.

Isely and Crowl, U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, p. 273.

30.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 67.

31.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 157.

32.

Ibid..

33.

Ibid.,

p. 158.

34.

Ibid.,

p. 157.

35.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

pp. 68-69.

36.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 161.

37.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 69.

38.

Ibid.,

p. 75.

39.

10th Amtrac Battalion, Report on Operations, Enclosure (a), p. 12.

40.

Ibid., Enclosure (a), p. 9.

41.

Isely and Crowl, U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, p. 283.

42.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 89.

43.

Ibid.

44.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 172.

45.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 98.

46.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

pp. 100-101.

47.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 190.

48.

Ibid.,

p. 134.

49.

Ibid.,

p. 175.

50.

Isely and Crowl, U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, p. 277.

51.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 103.

52.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 180.

53.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

pp. 118-20.

54.

Ibid.,

p. 124.

55.

Isely and Crowl, U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, p. 124.

56.

Ibid., p. 299.

57.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 194.

58.

Ibid.,

p. 190.

59.

Isely and Crowl, U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, pp. 296-297.

60.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 189.

61.

Ibid.,

p. 190.

62.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 131.

63.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

pp. 200-201.

64.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 134.

65.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 203.

66.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

pp. 136-137.

67.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 206.

68.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 139.

69.

Ibid.,

p. 142.

70.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 211.

71.

Ibid.,

p. 210.

72.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 146.

73.

Ibid.

74.

Shaw, Nalty, and Turnbladh, Central Pacific Drive,

p. 213.

75.

Heinl and Crown, The Marshalls,

p. 149.

76.

Interview with MGYSGT Thomas J. Grover, USMC, 15 June 1975.

77.

Ibid.

78.

Holland M. Smith, Coral and Brass (New York: Charles Scribner's Sons, 1949),

pp. 148-149.