In a world that communicates increasingly via commercial pay-per use networks, one's ability to communicate is tied to and understood within financial terms: "How much is this conversation costing me?"

Like Myerson, several scholars have sought to understand everyday life as the domain where people encounter and live social discourses, especially since the work of Lefebvre, de Certeau, Foucault and others. Grossberg (1993) offers the concept of disciplined mobilization, which articulates how social power, knowledge, and a call to consume helps to regulates life in the industrialized world on the level one's everyday passage through the cultural-commercial ecosystem. Disciplined mobilization describes the ongoing transformation of everyday life to a closed environment where people are increasingly enclosed within the bubble of their individual concerns, are connected to the rest of the world through technology yet operating in venues where the political has been largely banished. Marketing campaigns for mobile lifestyles are part of a disciplined mobilization articulated to an underlying belief that technology will solve problems that politics has not. To a consuming public encouraged by mass media to view political life as filled with fraud and deception, commercial visions of the mobile world promise technologically-enhanced agency in everyday life via specific services and hardware to impart such regulation (Hillis, 2003).

Methods

The analysis below pulls from a qualitative study of select multimedia, still image, and text-only representations found on Nokia.com from April 2002 to March 2004. The majority of these marketing representations were still on the site as late as the end of 2005. The study integrated several forms of textual and semiotics analysis to conduct a close reading of select representations found on the site that envision the roll of mobile phones in users' everyday lives.

Selection of texts. Popular culture today is replete with representations of mobile devices. Nokia was selected for analysis in this study due to (1) the company's focus on marketing, (2) the variety of rich media on its web site, and (3) the fact that the company has worked in tandem with the European Union to develop ideal technologies and ideal users to actualize a profitable "mobile information society." Nokia's emergence as the world's largest cell phone manufacturer was achieved in part due to its focus on consumer lifestyle through product and marketing innovation. The company adapted Geoffrey Moore's theories of technology-adoption life cycles in the early 1990s to research and develop product designs and subsequent marketing campaigns aimed at target demographic groups such as "trendsetters," "high-fliers," "poseurs" and "social contact seekers" (Steinbock, 2001, p. 279). Market segmentation studies led the company to concentrate on downstream issues, such as product design/aesthetics and global market segmentation, rather than upstream product homogenization, which was the strategy of Nokia's primary competitors. Some of the company's downstream innovations included heavy lifestyle marketing campaigns, artistic removable faceplates for certain models, nearly monthly rollouts of new models, and several new multi-model product categories with a focus on breakthrough models with advanced features and stylish designs.

Nokia.com is an interesting locus for research because it includes many interactive multimedia representations, which as a genre has only recently been the subject of critical study. Nokia's ideal mobile users, who are featured as characters in the many visual marketing representations on the site, are presented as enjoying enhanced everyday experiences via Nokia handsets designed to facilitate their particular lifestyles. In the analysis section below, several ads that portray mobiles as tools of identity performance are examined first, followed by an interactive multimedia interface that narrativizes MICTs as tools of social and cultural mobility. An analysis of an ad from a popular magazine is also included in the first section, and another non-Nokia ad is discussed in the conclusion to illustrate the near ubiquity of mobile narratives as they move around the pop media ecosystem.

Textual analysis. As a guide for qualitative textual analysis of visual media, I have drawn from several sources including Rose (2001), Alasuutari (1995), Parker (1999), and Lehtonen (2000). Rose discusses three issues often taken into consideration in textual analyses: (a) the importance of suspending preconceived judgments during analysis, (b) contradictions and assumptions/truth claims within text or images should be considered as possible discursive productions, and (3) constructions of social difference can also be analyzed. For Alasuutari, when trying to explore the discursive orientation of a text, "the object is always to detect paradoxes within the material" (p. 134). Several general guidelines for the textual analysis, based on the suggestions of these authors and from the literature on discourse analysis and semiotics, were developed for this study. These guidelines included the identification of key terms, analogies, metaphors, and umbrella concepts with attention to how they are used, in what contexts, and what their meaning is in each context; looking for cross-textuality among selected texts, paying attention to how key terms and metaphors change, alter, or stay the same in the different texts that are analyzed; looking for cross-textuality between selected texts and other cultural texts such as movies, television, or other advertising campaigns for mobile phones; and finally, paying attention to the visual semantics of each text to consider how design biases certain user experiences, covey possible meanings, remediate older visual media forms, or make cultural references.

Textual Analysis of Selected Ads

Nokia.com. The current version of Nokia.com directs users to sites that are country and region specific, but tend to be similar. During the initial study upon which this paper is partially based (sampling of texts took place between 2002 and 2004), Nokia.com was the principle site for all of English-speaking Europe. Both prior and current versions of the site have extensive sub-sites for each of Nokia's phone models, which narrativize a particular lifestyle associated with the combination of features unique to each model (e.g., embedded still-image and/or video camera, text and MMS messaging, world-roaming, custom ringtones, etc). Many of the marketing representations for the handsets are the same or similar - often with some of the same images and multimedia - across many of the country-specific sites.

The mobile users characterized on Nokia's handset sub-sites come in a variety of genders, races (sometimes with discernible signs of ethnicity), and lifestyles. However, the range of class portrayals is not so diverse. [4] Almost all of the mobile individuals portrayed on the Nokia sites are middle and upper-middle class. At least three distinct levels of mobile users are depicted. The top level is the business class of users. The executive class is shown as needing the latest, most advanced gadgets to stay ahead of competitors and to be always connected to the workplace and the information network. New technologies are often first designed for the perceived needs of the corporate market, since many corporations spend a lot of money on the latest gadgets in hopes of increasing employee efficiency (Schiller, 1984). The next level down is the upper middle class movers and shakers. These are often urban sophisticates and globetrotters commonly portrayed using cell phones with advanced imaging capabilities (taking digital stills and videos, and sending/receiving images and/or videos as messages) and web browsers. As shown in the second analysis section below, the "eye to eye" multimedia interface the for the 7250 model, these mobile users are depicted as using advanced handsets to extend their communicative agency and experiences of the world within their consumer lifestyles (i.e., social and cultural mobility).

Nokia's low-end phones [5] tend to offer possibilities for identity performance via customizable ringtones, wallpapers, and faceplates, as well as telephony, but not much else. They are targeted for the lowest level of mobile users who are represented by the male and female characters of one of the texts discussed in the first analysis section below, Nokia.com's interactive interface for its 3510i handset. [6]

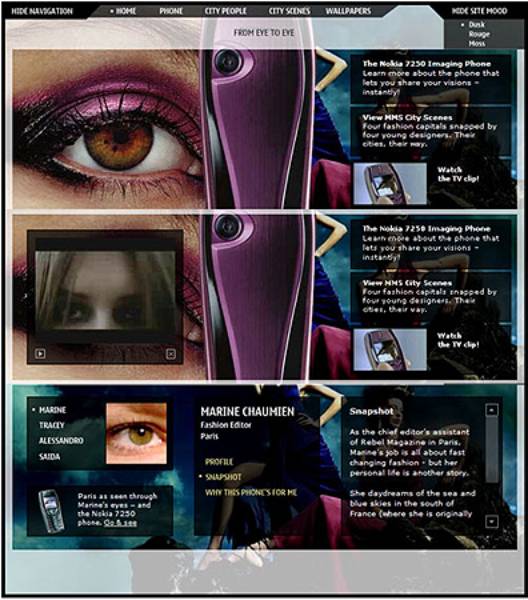

Figure 1. Composite of sections of the 3510i interface (source: Nokia.com)

PC users can click here to download the interface as an interactive EXE file.

Mobile experiences and performances. In many mobile marketing messages, handsets, especially those with advanced features, are presented as an avenue of expression for postmodern identity, allowing for multiple aspects of self identification to be displayed through static signs, such as custom wallpaper, to personal media, like photos or videos taken with one's mobile. Hence, the handset is presented as the base unit for mobile identity construction and performance. It is an icon for one's identity of the moment (more so than one's lifestyle). It is a mobile mini me. Take for example the three characters of Nokia.com's interactive multimedia interface for the 3510i handset who are shown above in Figure 1. Each of the four scenes featured within the 3510i interface depicts a user's phone with personalized faceplate and screen wallpaper as well as a picture that supposedly encapsulates what the personalized handset signifies: the user's identity. For example, the bearded man in the second scene (top of Figure 1) identifies as a man who "Likes Girls" and presents a particular style of masculinity and sexuality. His phone has a pink faceplate with an illustrated puckered-kiss image for the screen wallpaper. The visuals of the accompanying picture of the user portrays his idealized identity as a pimpish "lady's man." A part of the interface allows web visitors to practice customizing the 3510i handset by selecting from a variety of faceplates, wallpapers, and ringtones just like the three imaginary users presented by the interface have supposedly done. The interface also allows visiters to view two television ads for the 3510i, which both narrativize the "express what you like" theme. Click the images below to watch the movies.

Click

here to download and watch the first movie as a quicktime (.mov)

file. |

Click

here to download and watch the second movie as a quicktime (.mov)

file. |

Although the portrayal of the 3510i interface's characters seem perhaps intentionally over-the-top, its racist and sexist narratives are no less apparent or innocuous. The central theme of the interface, "express what you like," downplays the racist depictions of the "Stripes" section, for example, as if the say "so this black person likes stripes. What's the big deal?" Indeed, the fantasy-scape portrays this character as someone who perhaps frequently dresses in tiger prints. But the jungle-themed text certainly offers a comment on Blackness that comes through via the acknowledgement that all of the pictures on the interface are signifying these users' inner desires, fantasies, and visions of themselves. Thus, this black woman's essence - where/how she feels most at home and comfortable - is presented as being black and back in the jungle. What makes this text even more problematic is the inseparable conflation in the text of race, gender, and sexuality. The tiger-striped bikini and tight pants code this female character as possessing a wild, untamed sexual drive. This drive is not hidden, but exhibited for the pleasure of others, as further illustrated by the sexualized language, "Grrr!...How did you like that?...Stripes are grrreat!" In a way, the customized handset icon helps to obfuscate the intensity of this meaning-loaded text. By itself the handset with faceplate and wallpaper perhaps does not provide as many signs to deconstruct. It may represent one's identity, but it also presents a barrier to one's more intimate inner-self. People looking at this mobile could interpret the faceplate and wallpaper in a number of different ways, which is supposed to be part of the fun. The juxtaposition of the handset next to the fantasy-image also serves to divert attention from its content, which plays on stereotypes of black female sexuality. The handset is real. The picture is not. It is just a fantasy based on the user's personal choice of how to express her identity.

A late-night pick-up scene is similarly downplayed as an ageless and fun gendered mating ritual in a Nokia ad that appeared in Rolling Stone Magazine (June 12, 2002). The ad stresses the handset's ability to allow users to express gendered identity through the act of communication via both images and text messages anytime, anywhere. It presents several pictures of young adult men and women at a bar, which were supposedly snapped by someone using the built-in camera of a 3650. A caption above the pictures reads, "Hottie coming your way." A caption below the pictures reads, "The new babe alert." Mobile-mediated communication is shown here to be seamless. The technology melds easily with gendered behavior by mediating it, providing visual evidence to extend the pleasure of male bonding to the more permanent realm of image where the male gaze can linger on the now captured, and thus controlled, female bodies. The mobile becomes yet another technology of pleasure through the carnal density (Williams, L., 1998, 1995) of the interface and the way in which it mediates experience, bringing the immediate past into the visual regime of the screen, where the gaze can not only linger without social repercussion, but can also control and interact with the image. For such experiences to be ultimately pleasurable and immediately extending a sense of agency, the device must negotiate a delicate balance of seamless and easy use, aspects of control and interaction, and hypermediated visual appeal, thereby remediating and extending the gendered visual practices of other media like the web, television, and film.

Beyond the trope of man-and-his-technology, this ad targets young, middle-class men as videogame users. "The new babe alert" is portrayed as a variant on the old mating game myth, and actual modern western social practices, made possible by mobile technology. But the game has its limits. Imagine an absurd scene of people in a bar all looking at handsets, at images of people whose actual bodies are only a few feet away; the social dysfunction of such a scene would not make for a good ad. Instead, the Nokia ad is predicated on a sense of savvy, exclusivity afforded to early adopters who are stereotypically portrayed as young, white men. In this particular case, early adoption of both the technology and a particular user practice that the technology can impart is depicted as enhancing male users' cultural capital, and gaze, as adept practitioners of social and technologies competencies. These studs are flirting with their personal technology, entranced with its power, interface, and the sense of play enacted, even more than they are with the ladies. Not only does the device mediate a performance of masculinity and cultural/technological prowess, it also becomes a tool of social regulation within detailed practices of everyday life.

In many ads for mobiles, such as "The new babe alert," MICTs are shown to grant agency within everyday life and postmodern culture, a culture that is increasingly inundated and obsessed with signs, particularly visual and multimedia representation. From Jameson (1991), who defined postmodernism as the "cultural logic of late capitalism," and other scholars, postmodern culture is "the product of Western (post)industrial societies that have been moving towards post-Fordist arrangements of production," where enlarged middle classes in most industrialized countries have the financial power and commodity desires necessary to fuel a rampant cycle of production and consumption (Kang, 1999, p. 23). Visual media have largely been the delivery service for the language of postmodern sensibility and its abstract play of signs (Leiss et al., 1990; Kang, 1999), while transnational media giants provide much of the content. [7] Personalizable handsets like the 3510i are truly postmodern cultural technologies/commodities in that, like most other products, these handsets allow for performance through consumption in the form of purchase, ownership, and use, but they also allow for performance through bricolage display enabled by customizable features. Mobile identity companions seemingly allow for more flexibility and performative agency before the ever-present gaze of the Other. Mobile performances coalesce around the actual body in a more traditional sense than in computer terminal-mediated social interaction, and hence the body is subject to specific everyday disciplinary boundaries and gendered practices. In fact, the possibilities for postmodern subjectivity seem limited by what the 3510i interface says about identity, that ethnic, gender, and heternormative stereotypes are paramount in bodily performances.

The concept of performance has for many years helped scholars to understand and study identity practices. The relationship established between the female surfer and the shark (as the Other and in this case the Male Gaze) in the 3510i interface acknowledges that, as Judith Butler argues, "the self only becomes a self on the condition that it has suffered a separation...a loss which is suspended and provisionally resolved through a melancholic incorporation of some 'Other'...The disruption of the Other at the heart of the self is the very condition of that self's possibility." Postmodern identity is perhaps fulfilled most completely by one's ability and aptitude to express and distinguish oneself to the Other through consumption, to present one's consumption practices and actual possessions that express one's identification with an assortment of items from the cultural banquet. Nokia's downstream innovation in product design and marketing express a detailed knowledge and understanding of postmodern identity in this sense where mobiles are created as fashion and performance accessories to empower the individual in a culture obsessed with personal image.

Several marketing messages on Nokia.com portray mobile users of different shades-of-brown to associate commercial mobile devices with hipness and other supposed traits-of-blackness. Similarly, several Nokia.com texts associate the bodies of female models (portrayed as mobile users) with the sexy bodies and customizable features of specific handsets. Racist and sexist advertising practices have a lengthy history, but on Nokia.com, these stereotypical depictions are deproblematized through the invocation of individual choice and the identity flexibility/performance capabilities offered by customizable features of mobiles. The black female mobile user of the 3510i interface is able to choose safari prints to express her identity of the day not because she is black but because of the performance agency provided by her mobile handset. Cultural icons (e.g., erotic and urban motifs) can be selected by users when they want to represent aspects of their personal identity or by anyone who wants to perform what are seen as trends that may have cultural capital at any given time and place. Race, sexuality, and gender in this way become commodities to be adopted or discarded as a fashion accessory, depending on how individual users choose to navigate various social and cultural spaces via the agency supposedly afforded by mobile identity/bricolage companions. Or at least this is the promise and the preferred reading of these texts. But Nokia.com also demonstrates the limiting reality of mobile identity performance. By choosing to deploy stereotyped characters in their marketing representations, Nokia not only reminds us that the mobile world is not the Netizen's cyberspace utopian myth of individual empowerment and horizontal communication via new media technologies, but that commercial mobile device are actually being developed as a technologies of cultural control and consumption in the guise of individual agency and choice.

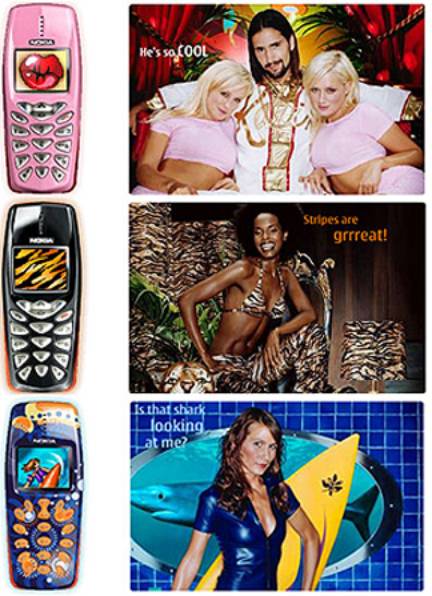

Nokia's eye on Europe and cultural mobility. MICTs often remediate (Bolter and Grusin, 2000) older ICTs like the telephone, radio, television, and web. Hence, narratives of mobile privitization (Williams, R., 1992), or cultural mobility, promising that technologies can bring the images and information of the world to the individual, are common. Nokia.com's interactive multimedia interface for the 7250 handset deploys postmodern advertising techniques to narrativize the corporation's vision of what is perhaps its ideal European mobile user who has enhanced cultural mobility by way of accesses to a wide array of digital cultural objects via the handset. The interface has four main sections: Home (where visitors can view the corresponding television ad for the 7250), Phone (where the main features of the handset are described), City People (where the lives of four 7250 users are described), City Scenes (where visitors can look at pictures of European cities taken by the four featured users), and Wallpapers (where visitors can download computer wallpapers/backgrounds based on the theme of the interface and its companion "Spotlight" movie). Clicking on City People causes new content to load in the center of the interface. A text blurb appears above this central content area, "Not for everyone? I'm not 'everyone'!" When the content finishes loading, what appears is a "profile" of Marine Chaumien, a fashion editor from Paris. Marine is 29. She loves "[c]areer, the south of France, travel to new places, Sicily, Italian food, green tea, movies, friends and family!" She detests, "[o]il damage on the beaches, violence, and unconscious people." Marine's profile also reveals her favorite book, piece of clothing, and "personal objects:" her palm pilot and video camera. Viewers can also opt to see Marine's "snapshot", a short synopsis of her urban lifestyle. This summary of her life also contextualizes Marine's elucidation for, "Why this phone's for me." In the snapshot, we learn that although her job is mired in the fast-paced, mercurial fashion world of Paris, her personal life is more tranquil. Not only does the 7250 fit well into both parts of her life but also into her refined sense of style: "The phone has a very aesthetic design based on simple lines, and is very small and light -so discrete! The Nokia 7250 is both my new professional 'must-have' tool, and my new toy. I love sending pictures to my boyfriend of places I wish he was there to share with me."

Figure

2. Composite of screen shots from 7250 interface (source: Nokia.com).

Click on the image above to

open the actual 7250 flash interaface.

Rather than being offered a headshot of Marine, as the interface's remediation of character profiles in video games might suggest, we are only offered a picture of her eye. Next to this picture is Marine's name above the names of three other designers from Western Europe- Tracey, Alessandro, and Saida. Rolling-over Tracy's name with the mouse causes the picture of Marine's eye to be switched out with what we are asked to assume is Tracy's eye. This behavior can be repeated with the other names as well. Clicking on any of the names loads content specific to each of the featured 7250 users. Browsing through the profiles, we learn that all of these designers live in urban cultural centers of Europe (London, Milan, Barcelona), and they all use the 7250 in both their work and personal lives. They all seem to be true European citizens in love with the places, food, and culture of their cities and of Western Europe rather than of a particular nation. For example, Tracy Body, a fashion designer from London, professes a passion for living in the heart of London and for "eating in Florence." All of these individuals are urban sophisticates who appreciate the 7250 for its modern design, and because it allows them to "explain things visually rather than verbally."

Each of the four profiles available in City People contains a link to a corresponding exposure in the City Scenes section of the interface-a section that contains pictures supposedly taken by each character within the scope of their daily lives. "Marine's Paris seen through the lens of her Nokia 7250 phone" consists of pictures and short text captions of fresh bread at her favorite grocery, an art exhibit, and her favorite cafes. Most of the City Scenes include some pictures of the designers themselves and of their friends as well. The users' profiles and pictures help to establish a concrete lifestyle group - made all that more real through specific examples of users' lives - to connect with the features and design of the 7250 handset. The profiles and pictures of the interface offer an exterior view of the content (artifacts, places, people) of these characters' lives, which is complemented by other multimedia on the 7250 sub-site (see Figure. 3) that narrativize interior subjectivities of mobile life through very abstract audiovisuals. We can more readily understand Marine's "daydreams of the sea and blue skies of the south of France," or Saida's dancing "on the sand under the sun or the full moon" on the Castilian coast, via the audiovisual ambiance of the 7250 "Spotlight" movie, for example (click here to view a slideshow of screen captures from the 7250 spotlight). The surreal Spotlight represents individual experiences of performtivity in the mobile world, whereas the interface as a whole represents the 7250 itself as a cultural artifact and its domain of action within the user's everyday life and cultural diet; As web site visitor's we can interact with fragments of the everyday life of the characters, navigating through images, text, buttons, and surfaces. We get to step into their shoes - or perhaps take on the role of one of their friends to whom they have sent images - by playing with the interface and seeing the pictures they have taken.

Figure 3. Screen capture of the main page of the 7250 sub site, including a video pop-up window. (source: Nokia.com). Click here to view a slideshow of screen captures from the 7250 web site and movies.

One of the most interesting elements of the 7250 interface is the use of eyes as icons representing each of the four users. Several sections of the interface feature pictures of one or more of a character's eyes. Some of these eyes are navigation buttons that can be rolled over to find out whose eye it is and clicked on to retrieve more details on that character's life. Rolling-over names in sequence reveals how different the four eyes are, highlighting the uniqueness of the individuals that the eye images are standing in for. The interface's exaggerated use of eyes represents a technique of hypersignfication. The advertising practice of decentering specific body parts emerged out of a "new realism" of postmodern advertising in the 1980s, treating "the part as an indicator of a subjectivity - the personality seems to express itself via the body part" (Goldman and Papson, 1994, p. 36). The highlighting of the unique aspects of each user portrays this handset as being personalizable to the differences in each person's personalities and lifestyles. Yet in a way, this contradicts the sameness of the users' lifestyles profiled by the interface. The characters of the interface are all young, active, progressive, artistic urban sophisticates. Perhaps above all they are European urbanites. They signify the ideal European mobile citizen of the overall worldview envisioned on Nokia.com. The mobile citizen is portrayed here as an enhanced (by mobile gadgets) consumer of culture (food, urban geography/places, shopping, art, etc.). They seek pleasure in everyday experiences, and their mobile technologies allow them to get the most out of life (i.e., the highest quality and quantity of experiences possible each day). Their love for Europe means a desire and enjoyment in consuming culture that traverses the local, regional, and international, the cultural banquet of consumer culture.

Undoubtedly, the people actually living in Western Europe encompass broad range of tastes. However, Nokia's vision of a particular "European" lifestyle group in this and other representations highlights, (a) the fact that the company has extensive regional/multicultural marketing campaigns, (b) that this vision corresponds with the European Union as a political project that entails the creation of European identities and foremost European consumers, and (c) certain aspects of national identity are potential barriers to regional and transnational consumer identities. Nokia's European stratagem is demonstrated, for example, by the company's website for France (www.nokia.fr). Although the French language is used on this site, the content is otherwise almost totally the same as that on Nokia's other country sites. The Nokia sites for the UK and Germany, for example, contain some unique narrative representations, but the content is still largely the same (e.g., an interactive multimedia interface on the German site has a different format than its counterpart on Nokia.com, but the visuals, especially the human characters, icons, and themes are the same). Nokia also broadcasts the same commercials throughout Europe, a practice used by many multinationals (click here to watch two commercials for the 3510i handset). Some commercials are dubbed into local languages, whereas others, especially those produced in English, are played without any alteration. Such strategies fit right in with Domzal and Kernan's (1993) suggestions for multicultural advertising: if the central meaning can be derived from a wide range of people through the use of certain visual cues, then ads can overcome language and cultural barriers. [8] They see the increase of globalized cultural products and postmodernism's focus on lifestyles, appeal to sense of self, the visual, etc., as producing a fertile climate for effective universal ads. These authors argue that multinational corporations increasingly need to transcend national marketing strategies, and they can do so through the universal language of postmodern advertising. General product categories like food and fashion are more successfully marketed through universal ads because such products appeal to the intimate human association and concern for the appearance of the body.

It is not surprising that a company like Nokia has created a vision of the ideal mobile user, which sees the mobile citizen as a cosmopolitan consumer who is not so much tied to local culture as they are interested in mobile presentation, bricolage and play. This vision of the mobile user turn citizen-consumer of a global information society can seemingly capitalize on perceived transnational cultural appeals and hence is proselytized within universal type ads. In the case of European markets, there are many common codes that pertain to consumer culture, globalized cultural products, and European identity, which Nokia adeptly encode into representations like the 7250 interface. This vision of the mobile European citizen where supranational identity is not in conflict with local identity in many ways overlaps and draws from other visions of the European citizen, in particular the vision developed over the last three decades by the European Commission, the policy branch of the European Union.

Although Nokia's homogenous vision for the mobile world and its citizenry is perhaps most fully developed in its commercial representations, its vision for a "Mobile Information Society" is also clearly represented in the company's policy documents. [9] Since the 1980s Nokia and other Europe-based cellular companies of that period participated in the EC's plans to develop a digital cellular standard that could uniformly cover all member states. By the 1990s, such policies grew into a more comprehensive plan for creating a "European Information Society." The EC's more recent policies for a networked "eEurope" recognize the need for local cultural representation, a fact that is somewhat acknowledged by the 7250 interface, but also diluted through its merging of Euro urban identities. In comparing these two visions of the mobile users, or citizens, of Europe, several significant similarities and differences are apparent. The Commission's mobile policy texts are consistent in tone and motivation (first economic, and then cultural and humanitarian) with the twenty-year history of the EU's information society agenda. Perhaps not surprisingly, commercial texts articulate more schizophrenic identities in their attempts to articulate a heterogeneous range of narratives that colonize understandings of the mobile world and its inhabitants. Both the EU's and Nokia's narratives envision the European citizen as a unit of consumption and labor. For the EU, this is important for the region's economic success and wellbeing; for Nokia is it is important for its own success and wellbeing. Consumption and taste involve minute social negotiations and contingencies (Bourdieu, 1984). However, European citizenship and identity, as projects of the EU and especially the EC, do incorporate understandings of citizens as consumers of local, national, regional and global products (including culture), and as laborers within the overall scheme of regional and global capitalism. Unlike Nokia, however, the EC also articulates other roles for the citizens in Europe and its member states, including "participation for all in the information society," digitization of local cultures and languages, and as participants in democratic forms of government, decision making, and civil society. Nokia's marketing efforts, on the other hand, envision hierarchies of devices and levels of participation/citizenship within everyday life. The attempts at universal advertising practices illustrate that actual designs and functionality of MICTs are influenced more so by the bottom-line mentality and strategies of multinational corporations than the cultural and communication needs and values of specific groups.

Figure

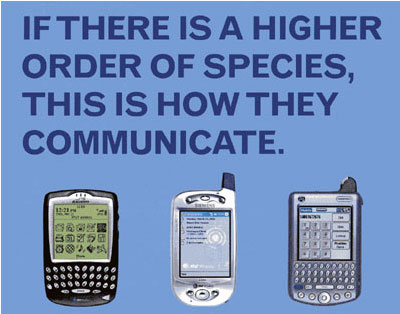

4. Part of an AT&T print advertisement.

(Source:

Wired Magazine, March, 2003).

Conclusion

The advertising representations analyzed above present narratives of life in the mobile world that are in fact rather limited, despite their promise of enhanced identity performance and cultural communication/access. In the first group, we see the remediation of gendered and racial stereotypes, which compromise notions of technological liberation, or at least enhance creative freedom. Such limited visions are in contrast to the identity-making practices that mobile phones have been brought into by teenagers and other groups. The second analysis highlighted Nokia's vision of the technology-enhanced consumer of cultural experiences in a world without political difference. Cultural and social mobility in this case certainly entails opportunities for interaction with cultural objects, personal images and interpersonal communication, but the narrative and technological functionality obscure or ignore many cultural and communicative possibilities in favor of a seemingly complete postmodern global capitalist regime.

MICTs are so attractive to big business, because they offer new modes of colonization of people's everyday life, extending the regulation of consumption on both a macro (ubiquitous) and micro (private life) scale. The two analyses above showed different types of mobile regulation, mediation of identity performances and mediation of cultural objects flowing to and from users, both of which work to make MICTs increasingly indispensable extensions of the human body. The classist nature of mobile narratives does not only exist in their commercial status; some people can, and others can't, afford these bodily extensions, which are powerful even in their limited designs and narratives. As acknowledged in the AT&T ad shown in Figure 4, the quality and quantity of a user's access to social and cultural spaces also depends on the level of mobile technology s/he has. This premise poses many challenges for equity and democracy in the actual mobile worlds in which people increasingly live. Do they have the best mobile devices with the most advanced and useful features and services? Do these features allow for creative control of cultural objects and collaborative group communication? Or are they mostly designed with economic value and logistics in mind? Do most users have the money to pay for access to social and cultural spaces whenever they want or need to? If mobile devices and ubiquitous technologies are to be mediators between individuals and their world, then such questions of access and quality have clear implications for citizenship in the mobile world.

References

Andrejevic, M. (2003). Tracing Space: Monitored Mobility in the Era of Mass Customization. Space and Culture, 6 (2), 132-150.

Barney, D. (2000). Prometheus Wired: The Hope for Democracy in the Age of Network Technology. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Berland, J. (2000). Cultural Technologies and the "Evolution" of Technological Cultures. In Andrew Herman and Thomas Swiss (Eds.), The World Wide Web and Contemporary Cultural Theory. New York: Routledge.

Birdsall, N., and Graham, C. (Eds). New Markets, New Opportunities? Economic and Social Mobility in a Changing World. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

Bolter, J. D., and Grusin, R. (2000). Remediation: Understanding New Media. London: MIT Press.

Bourdieu, P. (1984). Distinction: A Social Critique of the Judgment of Taste. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Caronia, Letizia, and Caron, Andre H. (2004). Constructing a Specific Culture: Young People's Use of the Mobile Phone as a Social Performance. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 10 (2): 28-61

Castells, M. (2000). The Rise of the Network Society (2nd ed.). Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

Churchill, E., and Wakeford, N. (2001). Framing Mobile Communications and Mobile Technologies. In Barry Brown, Nicola Green, and Richard Harper (Eds.), Wireless World: Social and Interactional Aspects of the Mobile Age (pp.154-177). London: Springer.

Coyne, R. (2001). Technoromanticism: Digital Narrative, Holism, and the Romance of the Real. London: MIT Press.

Domzal, T. and Kernan, J. (1992). Reading Advertising: The What and How of Product Meaning. The Journal of Consumer Marketing, 9 (3), 48-64.

Domzal, T., and Kernan, J. (1993). Mirror, Mirror: Some Postmodern Reflections of Global Advertising. Journal of Advertising, 22 (4), 1-20.

Eriksson, P., and Moisander, J. (2002). Consumption as Knowledge Production - Narrating the Use of the Communicator. Paper presented at the EURAM Conference, May, 2002, Stockholm, Sweeden.

European Commission. (2001b). eEurope 2002: An Information Society for All. Action Plan. Retrieved March 15, 2006, from: http://europa.eu.int/comm/information_society/eeurope/actionplan/index_en.htm

Firat, A. F. (1991). The Consumer in Postmodernity. In R.H. Holman and M.R.Solomon (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research, 18 (pp. 70-75). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Firat, A. F. (1991a). Postmodern Consumption: What Do the Signs Signal? In J. Umiker-Sebeok (Ed.), Marketing Signs. Bloomington, IN: Indian University Press.

Firat, A. F. (1992). Fragmentations in the Postmodern. In John F. Sherry, Jr. and Brian Sternthal (Eds.), Advances in Consumer Research, 19 (pp. 203-206). Provo, UT: Association for Consumer Research.

Garcia-Montes, Jose M., Caballero-Muñoz, Domingo, and Perez-Alvarez, Marino (2006). Changes in the self resulting from the use of mobile phones. Media, Culture & Society, 28 (1): 67-82.

Goldman, R., and Papson, S. (1994). Advertising in the Age of Hypersignification. Theory, Culture & Society, 11, 23-53.

Harmsas, J., and Kellner, D. (1997). Toward A Critical Theory of Advertising. Illuminations. Retrieved August 12, 2004, from: http://www.uta.edu/huma/illuminations/kell6.htm

Hayles, K. (1999). How We Became Posthuman. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Hillis, K. and Lillie, J. (2003). Spatial Technologies for the Mobile Class: Life in the Cooltown Ecosystem. Geography 88 (4), 338-347

Innis, H. (1951). The Bias of Communication. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Jameson, F. (1991). Postmodernism, or, the Cultural Logic of Late Capitalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Kang, M. (1999). Postmodern consumer culture without postmodernity: Copying the crisis of signification. Cultural Studies, 13 (1), 257-294.

Katz, J. (1999). Connections: Social and Cultural Studies of the Telephone in American Life. London: Transaction.

Katz, J. and Aakhus, M. (Eds.). (2000). Perpetual Contact: Mobile Communication, Private Talk, Public Performance. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Katz, J., Aakhus, M., Kim, H., and Turner, M. (2003). Is There a Culture of Mobility: An Examination of Young Users Perceptions of ICT. In L. Fortunati, J.Katz, & R. Riccini. (Eds.), Mediating the Human Body: Technology, Communication, and Fashion. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Katz, James E., Sugiyama, Satomi. (2006). Mobile phones as fashion statements: evidence from student surveys in the US and Japan. New Media & Society, 8 (2): 321-337.

Kling, R. (Ed). (1996). Computerization and Controversy. London: Academic Press.

Leiss, W., Kline, S., and Jhally, S. (1990). Social Communication in Advertising (2nd ed.). New York: Routledge.

Mick, D. G. (1986). Consumer Research and Semiotics: Exploring the Morphology of Signs, Symbols, and Significance. Journal of Consumer Research, 13 (June), 196-213.

Mick, D. G. (1988). Contributions to the Semiotics of Marketing and Consumer Behavior. In T. Sebeok and J. Umiker-Sebeok (Eds.), The Semiotic Web: A Yearbook of Semiotics. Berlin: Mouton de Gruyter.

Mitchell, W. J. (1994). Picture Theory: Essays on Verbal and Visual Representation. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press

Myerson, G. (2001). Heidegger, Habermas and the Mobile Phone. Cambridge, UK: Icon.

Nye, D. E. (1997). Narratives and Spaces: Technology and the Construction of American Culture. New York: Columbia.

Oksman, Virpi and Turtiainen, Jussi. (2004). Mobile Communication as a Social Stage: Meanings of Mobile Communication in Everyday Life among Teenagers in Finland. New Media & Society, 6 (6): 319 - 339.

Poster, M. (2006). Information Please: Culture and Politics in the Age of Digital Machines. Durham, N.C.: Duke University Press.

Robins, K. and Webster, F. (1999). Times of the Technoculture. London: Routledge.

Sherry, F. (1991). Postmodern Alternatives: The Interpretive Turn in Consumer Research. In Harold H. Kassarjian and Thomas Robertson (Eds.), Handbook of Consumer Research (pp. 548-591). Englewood Cliffs, NJ: Prentice-Hall.

Smith, M. & Marx, L. (Eds.) (1994). Does Technology Drive History. London: MIT Press.

Steinbock, D. (2001). The Nokia Revolution: The Story of an Extraordinary Company that Transformed and Industry. New York: American Management Association.

Schiller, Herbert. (1984). Information and the Crisis Economy. Norwood, New Jersey: Alex Publishing.

Tutt, Dylan (2005). Mobile Performances of a Teenager: A Study of Situated Mobile Phone Activity in the Living Room. Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, 11 (2): 58-75.

Webster, F. (1995). Theories of the Information Society. London: Routledge.

Williams, L. (1995). Viewing Positions: Ways of Seeing Film. New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press.

Williams, L. (1989). Hard core: Power, Pleasure, and the Frenzy of the Visible. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Williams, R. (1992). Television: Technology and Cultural Form. Hanover: Westleyan University Press.