|

Ecce

HyperNietzsche:

HyperNietzsche: Model for a Research Hypertext In-conclusion: Toward the Philology of the Future? Introduction [1] The name Friedrich Nietzsche should not come as a surprise in a journal dedicated to the study of new media. Although Nietzsche, born thirty years before the industrial production of the typewriter, composed almost everything by hand, he was both a forerunner and herald of the digital age -- a precursor, let us say. [2] Indeed, his thought -- and even his practice -- prepared the way for much of the theory that underpins and accompanies new media work. Although the main section of this essay is dedicated to a straightforward and workmanlike presentation of the HyperNietzsche Project, I begin by cataloging some reasons why Nietzsche deserves to be called a precursor. It is not a case I will make in detail here, but through this introduction and the conclusion -- in which I suggest ways of bringing Nietzsche's thought to bear on new media issues -- I hope to show that HyperNietzsche should be interesting to readers of this journal not only because it is "Hyper," but even more so, because it is "Nietzsche." In other words, my secondary aim is to make a provisional case for why Nietzsche, by virtue of both his historical influence and the continuing challenge of his thought, deserves the attention of those concerned with new media issues. A few salient examples will suffice to indicate how Nietzsche's thought foreshadows what we might call the post-Bush era. [3] Consider Nietzsche's emphasis on multiple interpretations over a single "truth" or simple "facts," [4] and his famous definition of truth as "a mobile army of metaphors, metonymies, and anthropomorphism. Truths," he continues, "are illusions about which one has forgotten that this is what they are". [5] More generally, we can cite the concept of perspectivism that informs so much of his work. To quote one of the more explicit formulations: "there is only a perspective seeing, only a perspective 'knowing'; and the more affects we allow to speak about one thing, the more eyes, different eyes, we can use to observe one thing, the more complete will our 'concept' of this thing, or 'objectivity' be." [6] This all sounds quite familiar, almost clichéd, in contemporary media theory circles. It is reflected in the inherent instability of hypertext, which has no single, fixed, final version. Hypertext is non-linear, has permeable borders, and its structure changes in response to the actions of each reader. As Michael Joyce puts it in a frequently cited definition: "hypertext is reading and writing electronically in an order you choose; whether among choices represented for you by the writer, or by your discovery of the topographic (sensual) organization of the text. Your choices, not the author's representations or the initial topography, constitute the current state of the text. You become the reader-as-writer ... the new writing requires rather than encourages multiple readings. It not only enacts these readings, it does not exist without them." [7] And in the time since Joyce's article, a great deal more has been written on what editors of a recent collection of essays refer to as "the fluid and dynamic ontology" of electronic texts. [8] Perspectivism is, at the very least, a powerful metaphor for the emerging theory and practice in internet-based work in the arts and humanities. It is manifest, for example, in the Ivanhoe Game that is being developed by two leading theorist of new media scholarship, Jerome McGann and Johanna Drucker, for the purpose of using "digital tools and space to reflect critically on received aesthetic works." [9] As McGann explains, the game puts into practice a critical theory that is premised upon the instability and multi-vocality of the texts being studied. Now, it is certainly true that great works of literature have always spoken in many voices to many people, but digital media in an Internet setting emphasize and amplify certain aspects of literature that the conventions of paperbound bookmaking and reading tended to obscure and curtail. The model of oral literature -- think of the Homeric epic before it became fixed in writing -- may provide a useful analogy here. In a strictly oral mode the composition of a story is much more fluid and more subject to variations deriving from the perspective of the teller. While obviously different in many respects, hypertext shares something of the protean dynamism of oral traditions. [10] A more concrete example of something like Nietzschean perspectivism in the new media environment is provided by the conjunction of hypermedia technologies and emerging theories of textual editing. According to the previously dominant editorial model, the so-called copy-text theory championed in the mid twentieth century by W. W. Greg and Fredson Bowers, the editor works toward establishing an ideal text, presented on the page as a clear reading text, while variant readings and the history of the production and constitution of the text are either relegated to an apparatus criticus or elided altogether. In contrast, many contemporary editors no longer aim to establish an ideal, clear and stable text, but rather endeavor to represent and communicate to the reader the full complexity of the textual situation: the genetic history of the text, its various readings, the history of its transmission, and so on. The texts that result do not necessarily speak with a single voice; they tend to be less stable, less fixed, polyvalent, witnessed from multiple points of view ...in a word, more perspectivist. [11] The emergence of hypermedia has played a remarkable threefold role in the development of contemporary editorial theory and practice: 1) the rise to prominence of digital media for textual transmission has forced a radical re-thinking of what textuality is; 2) hypermedia have been, and continue to be, tools with which new theories and practices can be tested; 3) hypermedia have embodied and in some cases afforded tentative confirmation of these theories. Behind all of this lies a perspectivist paradigm of knowledge derived at least in part, often indirectly and without acknowledgement, perhaps even unawares, from Nietzsche. Still more can be said about Nietzsche's kinship with digital culture. His playfulness, persistent irony, and love of masks (Zarathustra, or the gay scientist, or the antichrist, or Dionysus) evoke the prevailing spirit of new media practitioners. [12] Furthermore, despite some youthful dalliance, throughout his maturity Nietzsche was an ardent advocate of transnational culture and an opponent of all forms of parochial nationalism, and so in a sense he was an early proponent of the global culture that recent technologies have so greatly facilitated. [13] Finally, just as one often finds in new media theory and practice a tendency toward the subversive and deconstructive, a certain passion for the antiestablishment position, [14] this too was surely characteristic of Nietzsche. He was the self-titled "Antichrist," who once described himself as "a subterranean man... who tunnels and mines and undermines" and who wrote in his autobiographical final book, Ecce Homo: "I am no man; I am dynamite." [15] Less obvious, perhaps, than Nietzsche's theoretical kinship are the ways in which his formal practice anticipates cybertextual conventions. Take, for example, his favored literary form: the aphorism. Of variable length but always relatively brief, it is a single unit that can stand independently, and yet is also deeply integrated into the structure of the whole; this unit is linked to aphorisms that proceed and follow it, and is often linked by allusion or thematic concern to aphorisms in other texts. Similarly in the realm of hypermedia art, discrete units share this dual imperative: they must both function independently and must also link meaningfully to many other units. As one final example, I cite Nietzsche's late, riveting volume, Nietzsche Contra Wagner. Although not usually mentioned alongside, say, the cut-up novels of William Burroughs or Julio Cortazar's Hopscotch as a forerunner of hyperfiction, Nietzsche Contra Wagner consists entirely of passages, mostly aphorisms, excerpted by Nietzsche from earlier writings and reassembled to form a new book. Nietzsche Contra Wagner thus illustrates the flexibility and portability of the aphorism form and also demonstrates how Nietzsche's aphorisms are, to borrow a phrase from new media theory, "deeply interwingled." So Nietzsche surely has a place at the table of new media theorizing. And yet he may not turn out to be the most welcome of guests, since he is in the habit of raising discomforting questions. I shall turn to some of these questions in the concluding section of this essay. First, however, ecce HyperNietzsche.

Model

for a Research Hypertext Overview HyperNietzsche is the model for a research hypertext that enables a delocalized community of specialists to work in a cooperative and cumulative manner and to publish the results of their work on the Internet. [16] The project has three main objectives:

While this particular venture focuses on Nietzsche, it has from the start been conceived as a pilot project. In principle, this model for a research hypertext could be used for a vast array of applications beyond the study of Nietzsche. In fact, the project is purposefully designing technological, administrative, and legal structures that can be generalized and can serve as a paradigm for the development of other research hypertexts. This is one reason why the HyperNietzsche project is dedicated to the Open Source model, not only for programming and design, but also in regard to intellectual property issues. [17] One can most easily imagine the HyperNietzsche model applied to the study of other authors, and indeed, the HyperNietzsche team has already launched exploratory projects with research teams working on Arthur Schopenhauer, James Joyce, Virginia Woolf, and Euripides, to name just a few. Work has also begun on hypertexts dedicated to Leonardo da Vinci and Giacomo Puccini. Other projects can also be imagined, for example, a hypertext dedicated to an historical event (e.g., the fall of the Berlin wall, or the 1969 moon landing) or one dedicated to a philosophical issue (e.g., the will, or first-person authority). The HyperNietzsche Project was originally conceived in 1996 by the Italian Nietzsche scholar Paolo D'Iorio as a way to employ emerging web-based technologies to solve long-standing philological problems associated with critical editions. Subsequently, in the late 1990s at the Institut des Textes et Manuscrits Modernes (ITEM) in Paris the project began to take shape. Still concerned at the time with problems of critical editing, it had also transformed into a new and expanded concept: the research hypertext. In the research hypertext, providing source material and secondary scholarship that can be easily navigated by the user to optimize efficiency is only the first step. It also provides for the complex, dynamic integration of these materials; it serves as a powerful tool to be used by scholars as they pursue their research; and it provides a new publishing venue with worldwide distribution able to support scholarship in hypermedia format. The decision was eventually taken to create the HyperNietzsche Association, which is governed by an Editorial Board of internationally recognized Nietzsche specialists who are elected every two years by all the members of the Association. Anyone who a) has published in the hypertext, and b) has one letter of recommendation from a current member, qualifies to be a voting member. A system was also designed to allow for anonymous peer review by the Editorial Board of all contributions submitted to the hypertext. These administrative structures -- the Association, the Editorial Board, and peer review -- help to ensure the quality of the material, the prestige value of the hypertext as a publishing venue, and the long-term self-sustainability of the project. As the project progressed, it became evident that the research hypertext can greatly enhance the potential for scholarly collaboration both geographically and in terms of academic discipline. Thus even as the project was being developed at the ITEM in Paris, it began to attract collaborators in Germany, Italy, the United States, and elsewhere, and it brought together not only philosophers and philologists, but also web designers, computer programmers, legal scholars, and others. [18] Since the reception in 2001 of a major grant from the German Humboldt Foundation, the HyperNietzsche project has burgeoned. The infrastructure has been completely redesigned; a legal agreement has been reached between the HyperNietzsche Association and the Nietzsche Archives in Weimar; and thousands of pages of manuscripts have been digitized and made available on line. In the course of its history, HyperNietzsche has seen the light of day in four versions. Each has been more functional than the previous one, but none has yet been fully operational. Thus, HyperNietzsche Version 1 has not yet been released. Rather, in December 2001 Version 0.1 was released, which allowed users to read essays that had been submitted. Subsequently, Version 0.2 was also able to accept the submission of essays. And in June 2003 the release of Version 0.3 allowed users to navigate through some of the primary material and to submit, and thereby publish, facsimiles. A user entering the HyperNietzsche website will first come to the Welcome Page, with a choice of six languages. Choosing English, the user will be brought to the English version of the Homepage [fig. 1]. [fig. 1]

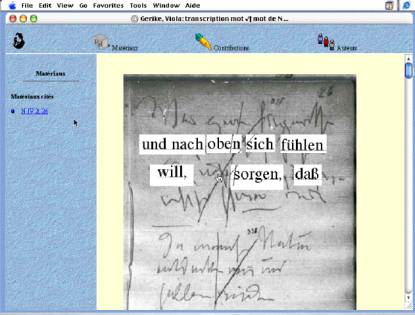

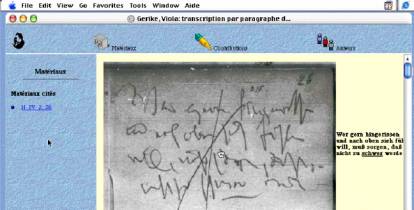

Three Key Concepts Let us now move more deeply into the structure of the hypertext. I shall introduce three concepts that will help to explicate how HyperNietzsche works: Dynamic contextualization is one of the central principles of the research hypertext. Put simply, it means that whatever one views in the main window of the hypertext will be immediately and automatically contextualized, so that in the frame surrounding the main window, all the material in the hypertext relevant to the page currently being viewed will be readily accessible. Let us look at a maquette taken from a demonstration version of HyperNietzsche to illustrate this. [19] [fig. 2] In fig. 2, the main window of the hypertext interface shows a digital facsimile of page 26 of a notebook, which the Nietzsche archivists have titled N IV 2. The three principle areas of the hypertext that we saw on the Home Page [fig. 1] -- Materials, Contributions, and Authors -- are now represented across the top of the screen as icons and they have been contextualized. On the Home Page, as we saw previously, the categories referred to the entire contents of HyperNietzsche. The Materials link gave access to all the material in the hypertext, and likewise with the Contributions, and Authors links. Now, however, each of these icons refers exclusively to the section of the Hypertext that has just been accessed, page 26 of Notebook N IV 2. Clicking now on the Materials icon (the safe) will call up in the frame on the left hand side of the screen only those materials relevant to the page currently being viewed. (This is represented in fig. 2.) If the Contributions icon (the pen) were to be selected, the left hand frame would contain a list of those contributions in the hypertext relevant to this page -- for example, there would be links to any articles that discuss the contents of this page. The Authors icon, meanwhile, will call up links to authors who have published material relevant to this page. More specifically now, when p. 26 of notebook N IV 2 is contextualized [fig. 2], the Materials section will include links to both black-and-white and color facsimiles in both pdf and jpg formats. The user will also have access to any transcriptions of p. 26 that have been published on the website. Since Nietzsche's handwriting is extremely difficult to read, many users will want to rely on the transcriptions prepared by experts. Here the advantages of digital technology come powerfully to the fore: users can be looking at a manuscript page and, with a click of the mouse, they can activate transcriptions of individual words, lines, or whole paragraphs. The images below illustrate various methods of displaying transcriptions. Fig. 3 shows an interactive word-for-word transcription, in which the user clicks on each word to view its transcription. In fig. 4, a simple linear transcription of the page appears to the right of the facsimile. A so-called "diplomatic" transcription, which encodes information about the appearance of the written page, could also be accessed, as well as the so-called "ultradiplomatic" transcription [fig. 5], which appears as a transparent overlay. In this last, the user can activate either the facsimile page, or the transcription, or both simultaneously. [fig. 3 interactive word-for-word transcription] [fig. 4 interactive paragraph transcription -- partial view] [fig. 5 transparent interactive transcription -- partial view] In these images, the background blue indicates that the Materials contextualization has been activated, whereby the user has immediate access via links to facsimile pages and to the various transcriptions. If the Contributions contextualization were to be activated, a yellow background would appear and links would be provided to all the secondary scholarship --critical essays, philological commentaries, etc. -- relevant to the same page. Activating the Authors contextualization, which is signaled by a pink background, would provide links to any scholars who cite this page in their contributions. Dynamic contextualization, moreover, does not only apply to the primary materials (e.g., manuscript pages). Rather, every item in the hypertext is immediately contextualized as soon as it is viewed. For a more detailed explanation of what it means to contextualize a Contribution (e.g., an interpretive essay) or an Author, I refer you to the project description on the website, currently located here (follow the link for "dynamic contextualization"). In summary, dynamic contextualization simply means that the frame surrounding the page viewed changes, is contextualized, relative to the page. 2. The Pearl/Pearl-Diver Model and the Signature System These terms refer to the information infrastructure of the hypertext. To illustrate them, let me first identify three key features of the HyperNietzsche infrastructure:

These three features are part of the pearl/pearl-diver model. The word "pearl," when used by HyperNietzsche programmers, is a specialized replacement for the common programming term "object." The image to have in mind here is one of pearls in the ocean and a deep-sea diver looking for them. Each element in the hypertext -- e.g., a manuscript page, or a whole notebook, or an interpretive essay -- is a unique pearl with an individual name. Moreover, one pearl may contain within it any number of other pearls. For example, one of Nietzsche's notebooks would count as a single pearl, but each page within that notebook would also count as a uniquely identifiable pearl. And even the definition of the relations between each pearl and every other pearl counts as a pearl in itself. One part of the pearl/pearl-diver system acts as the diver that searches for and retrieves the pearls. Pearls can be joined to one another in chains -- strings of pearls -- that can be constantly reordered and reconfigured. Because each pearl -- in other words, every element of the hypertext -- has a unique name, it is easy to generate individual chains according to a predetermined sequence or according to a new sequence established by the user. When a user clicks through a notebook page by page, the system is generating a chain that has been pre-determined by the hypertext designers. In contrast, when a user reorders elements in the hypertext a new sequence is generated. For example, a scholar wanting to trace the genesis of the concept of the superman (Uebermensch) could find every mention of the word in Nietzsche's manuscripts and place them in chronological order. This would generate a new sequence, called a "genetic path," which could then be made available to other researchers. According to the pearl model, each unit in the hypertext has a unique identity. These units are named according to the signature system. The signature system constitutes the response to a simple question: what is the smallest practical unit of significance in the author's oeuvre? The answer will vary according to the practices of the author, the scholarly tradition, and the consensus of specialists. For the study of James Joyce, for example, a strong case can be made that the relevant unit is the individual word. In the case of Nietzsche's published material, the most obvious unit -- and the one chosen by this project -- is the aphorism (or, in some cases, the paragraph). For the notebooks, the relevant unit is the individual note. [20] In summary, the pearl model means that each element in the hypertext has a unique identity, and the signature system is the logic of signification that governs the naming of pearls. Accessing a manuscript, the user begins at the highest level of what is called granularity [fig.6]. [21] The term granularity simply refers to the hierarchical organization of the various levels of the hypertext. [fig. 6] For manuscripts, there are three levels of granularity. 1. The manuscript as a whole [fig. 6], at which level one can see the entire manuscript and can go to specific pages simply by clicking on the page. Doing so brings one to the second level... [fig. 7] 2. The page [fig. 7] can be viewed in both color and black-and-white facsimiles and the zoom function allows three levels of magnification. The names of the scholars who prepared the page are cited at the top (clicking on the Authors button will call up their names and a link to their profiles with c.v. and a list of contributions), and options for downloading and printing the page are available on the upper right hand side of the window [fig. 8]. [fig. 8, partial view] 3. Clicking on a particular note brings the reader to the third level of granularity. The note is immediately identified through a contrasting background, and if the note extends over more than one page, the additional pages are brought into view. As with the page, the note can be displayed in various magnifications and can be downloaded and printed [fig. 9]. [fig. 9] Taken together, the signature system and granularity ensure that all elements in the hypertext -- every facsimile, transcription, essay, etc. -- can be precisely identified with a clear and simple web address. From an academic point of view, this is a crucial feature because it guarantees a reliable system of citation. Working with the Hypertext It takes no special talent to imagine fruitful ways to use a resource like HyperNietzsche. We have already grown accustomed to having instant access via the Internet to texts and images of all sorts. For many scholars and artists, their work would be unthinkable without it. In this regard, the technical, legal, and administrative innovations introduced by the HyperNietzsche model promise a more comprehensive, more efficient, and more reliable source for something that has already permeated the culture. Although in an important sense the research hypertext is open-ended, HyperNietzsche can also be said to be comprehensive in the sense of complete if and when it furnishes access to the essential primary materials for the study of Nietzsche: his published writing and the Nachlass, including all of the manuscript material. While the ultimate fulfillment of this goal lies in the future, major steps have already been taken, and anyone who works on Nietzsche can easily imagine the concrete benefits of having such access. No less significant, however, is the efficiency promised by a well-designed research hypertext. Dynamic contextualization offers an intuitive and user-friendly solution to the question of how to organize such large quantities of materials. A further requirement for genuinely useful Internet resources is the one that fails to be met each time a user clicks on a dead link. Dead link syndrome is as irritating as it is inevitable, and it is only part of the much larger issue of how electronic resources will be maintained and preserved. Though not the only nor necessarily the ultimate response to this challenge, the legal and administrative structures of HyperNietzsche aim to ensure the reliability of these resources in perpetuity. The research hypertext has much to offer its users beyond the furnishing of primary sources. We saw above how the contextualization feature fully integrates scholarly work both with the original material and with other scholarship. The hypertext also greatly facilitates the use of digital facsimiles of the original material in newly created secondary work, and it exploits new media technology to re-organize and link up material in ways that can shed fresh light on the author's thought and his compositional practice. The hypertext can be of threefold service here: as the source for the primary materials the scholar is studying; as a tool to assist with searching and organizing the material; and finally, as the perfectly suited venue for presenting and disseminating the results. To offer just one simple example, philologist Inga Gerike has prepared a study of the genetic history of aphorism 338 of The Wanderer and his Shadow, Vol. II of Nietzsche's Human All Too Human. It locates earlier versions of parts of the aphorism as they appear in Nietzsche's notebooks, revisions he made in the fair copy prepared for the printer, and instructions to change the text, sent by Nietzsche on a postcard to his publisher. The result traces the evolution of the passage and offers an approach to understanding both Nietzsche's practices as a writer and the meaning of this aphorism. The hypertext version of the study once completed will include links to the manuscript material, all of which will be available in HyperNietzsche with transcriptions (as we saw above), as well as a link to the published aphorism in the first edition of The Wanderer and his Shadow. The hypertext can display such genetic studies in various formats, and it can also generate a rhizome which shows how various genetic paths cross, diverge, fork, conclude, and connect to other paths. Fig. 10 shows a rhizomatic display of the first sections of three genetic paths (red, green, blue) prepared by Gerike. By scrolling to the right, the reader can follow the paths, which all eventually lead to the link for Aphorism 338. [fig. 10] In the multimedia environment, audio-visual material can also be incorporated. In the case of Nietzsche, music played a crucial role in his life and thought. He wrote passionately about the music of others -- Wagner and Bizet, for example -- and even authored his own compositions. HyperNietzsche can easily incorporate musical recordings and make them readily available at appropriate points in Nietzsche's texts. Links can also be made to worthy film material, such as documentaries or stagings of operas. Needless to say, a research hypertext on Giacomo Puccini or Orson Welles for example would exploit this capacity a great deal more. In-conclusion: Toward the Philology of the Future? [22] Whether the HyperNietzsche model will become a widely used paradigm for humanities research, and for other kinds of work in the arts and sciences more broadly, is of course impossible to say. The electronic world is restless, shape-shifting, constantly transforming and re-inventing itself. HyperNietzsche, as part of that world, is itself constantly changing as it develops internally and responds to its environment. In adopting Open Source as both the technological basis and the guiding ethos for the project, the founders of HyperNietzsche have embraced the radical dynamism -- and fundamental uncertainty -- of the digital world. [23] Open Source dictates that either the HyperNietzsche model will lead the way, constantly being improved by the work of many hands; or it will yield place to a superior model. Even acknowledging such instability, reflection on HyperNietzsche can still allow us to make some concrete observations about the future of humanities scholarship. As one of the most innovative projects in digital research in the humanities, it affords a perspective on what changes have already taken place or are now underway. Perhaps the most obvious changes cluster around the availability of primary sources. Heretofore, if one wanted to study Nietzsche's manuscripts or personal library, one had to go to Weimar, had to secure permission, had to follow the rules of access, and so on -- conditions which applied, or still apply, equally to the study of very many other authors. Scholars and artists who have concerned themselves with such authors have, for the most part, not based their work on the direct study of the primary materials. Manuscript study has been, and still remains, a highly specialized field. This is no insignificant matter, as the case of Nietzsche proves. For many years the vast majority of the readers of Nietzsche relied on faulty, at times radically faulty, editions of his work. The most significant and notorious situation regards Nietzsche's notebooks and drafts from the 1880s. These papers, assembled in an order Nietzsche never intended and published (something he also did not intend to have happen) posthumously as a book, are now known to the world as Der Wille zur Macht -- The Will to Power. This book has been so influential that it is virtually impossible to understand 20th century western philosophy -- and quite a bit of western culture more broadly speaking -- without studying it. And yet much of this influence has been based on the false sense that the book is Nietzsche's magnum opus, the most authoritative statement of his mature philosophy. Certainly, responsible and reliable critical editions can go a long way toward ameliorating such situations, as in fact has been in done in the case of Nietzsche with the widely respected, and currently most authoritative, Kritische Gesamtausgabe. [24] Yet it is undeniable that any edition, indeed any transcription, is already an interpretation. It may well be that in very many cases, these interpretations are entirely uncontroversial. But the number of controversial cases for a large number of authors, and certainly for Nietzsche, is far from negligible. Hitherto, the vast majority of scholars and artists reading Nietzsche, or just about any major author, simply had to rely either on faulty or not-so-faulty published editions. The sheer material conditions, i.e., access to the primary material in the archives, determined this. Now, almost suddenly, the mediation between reader and primary material has been, or is in the course of being, radically reduced. [25] HyperNietzsche has already digitized thousands of pages and is currently making them available, worldwide, at no cost. Other authors' manuscripts have also already been digitized and many more are soon to come. [26] What impact will this have? For editors and manuscriptologists, the impact will be tremendous. The establishment of texts is bound to become ever more intensely debated: from the transcribing of handwriting to the ordering of pages to the methods for dealing with and presenting multiple and variant readings. With what results? It may be that versions will proliferate and editions will multiply, with none attaining authoritative status. Alternatively, one might imagine that with ever more eyes looking at the manuscript pages and ever more brains attempting to decipher them, so ever more accurate transcriptions, translations, and editions will emerge and new administrative systems and authoritative bodies will develop capable of evaluating and organizing the presentation of this new material. [27] The results and consequences remain to be seen, but as far as textual editing is concerned, the Rubicon has already been crossed. For readers and students of Nietzsche who are not inclined to study manuscripts -- again, this is currently the vast majority -- one can only wonder whether pressure will mount to learn to read manuscripts. Given the difficulties inherent in reading many authors' manuscripts, certainly Nietzsche's, it may seem unlikely that this could ever become a prerequisite for other modes of critical work, such as philosophical criticism. And yet, thinking by analogy, it was not so long ago that scholars at major universities did not need to know how to use word processors or how to do electronic searches. Surely, some still do not, but they are now in the minority. Expectations in these matters do change over time. Perhaps the widespread availability of source material will attract more students to their study; and perhaps also, the prima facie advantages of less mediated access to the originals (analogous to the advantages of being able to read texts in the original language) will behoove serious students to study them in digital form. [28] New media initiatives like HyperNietzsche raise a host of additional issues that are currently being hotly debated in and out of the academy. They have prompted serious rethinking in regard to intellectual property law, the economics of publishing, the career trajectories of academics (especially in regard to publication-sensitive tenure decisions), and the policies of libraries and archives. Rather than pursuing these matters, which are already prominent on the new media theory agenda, I would like to conclude by raising a different set of issues, ones that arise from an attempt to think through some Nietzschean perspectives on new media and culture. For clarity's sake, I will break down into three questions what is in reality a knot of interrelated concerns. 1) In The Birth of Tragedy, Nietzsche offers a memorable depiction of the Alexandrian character of modern culture: "Our art reveals this universal distress: in vain does one depend imitatively on all the great productive periods and natures; in vain does one accumulate the entire 'world-literature' around modern man for his comfort; in vain does one place oneself in the midst of the art styles and artists of all ages ...one still remains eternally hungry, the 'critic' without joy and energy, the Alexandrian man, who is at bottom a librarian and corrector of proofs, and wretchedly goes blind from the dust of books and from printers' errors." [29] A hundred and thirty years later, one may need to replace "the dust of books" with "the glow of monitors," but the image still works; it still expresses a deep and widely felt dissatisfaction about post-Enlightenment culture for which Nietzsche was merely the most eloquent spokesman. The complaint is prominent in The Birth of Tragedy, and it recurs in various forms throughout Nietzsche's oeuvre. As the tone of the previous quote suggests, at first pass it registers like a complaint about pedantry, charging that modernity has elevated pedantry to a cultural ideal. Yet this complaint is part of a more profound skepticism about knowledge that is central to Nietzsche's thought (though not unambivalently so, as we shall see). The most succinct formulation, which Nietzsche calls "the doctrine of Hamlet," states simply that "knowledge kills action." [30] In his notebooks of this period, Nietzsche writes of how the "unrestrained knowledge drive" threatens to undermine culture, a danger he explores at length in the sequentially published Untimely Meditations. [31] Of the second Meditation, "On The Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life," Nietzsche would later write: "[it] brings to light what is dangerous and gnaws at and poisons life in our kind of traffic with science and scholarship." [32] The concern recurs later as well, for example in the Preface to The Gay Science where Nietzsche writes disparagingly of "the will to truth, to 'truth at any price'." In sum, the position Nietzsche urges us to consider in such passages holds that a scientific culture, a culture that has as its highest value the optimization of knowledge, must ultimately be self-destructive. There is, Nietzsche is suggesting, a fundamental antipathy between the desire for and drive for knowledge and the illusions which are necessary to sustain a vibrant cultural life. This line of thought in Nietzsche can be summarized in the following remark from an early notebook entry: "it has proven itself impossible to erect a culture on knowledge." [33] As so often in Nietzsche, however, the line just sketched out certainly has a countercurrent. Nietzsche himself was a trained and accomplished philologist who entered the field at a time when its "scientific" status was at an apex. He understood and respected the scholarly mode of inquiry, and even toward the end of his career, he could still write, "It is not for nothing that I have been a philologist, perhaps I am a philologist still, that is to say, a teacher of slow reading." In this passage he goes on to praise the philologist's mode of reading, "slowly, deeply, looking cautiously before and after." [34] Surely Nietzsche is not here writing in praise of pedantry, but it does nevertheless temper the critique of Alexandrian man we saw above. The acknowledgment here and elsewhere of the virtues of philology are symptomatic of a countercurrent that runs deep in Nietzsche's thought. Its most compelling expression comes in The Gay Science passages about "intellectual conscience." There Nietzsche writes approvingly of "the desire for certainty" as "that which separates the higher human beings from the lower." [35] In this and similar passages, Nietzsche seems to characterize the will to knowledge as something like an existential imperative. To "become what one is" -- as the subtitle to Ecce Homo puts it -- means to embrace this imperative. Now is not the time to explore further this apparent tension in Nietzsche's thought, but what we have seen suffices for our current purposes. From a certain perspective, projects such as HyperNietzsche epitomize the "scientific culture" that Nietzsche so colorfully satirizes. The Nietzschean concern here is not whether such projects succeed or fail, nor what impact they have, but rather it is a concern about the desire they manifest. Does the energetic exploitation of digital technology in the arts and human sciences bespeak the triumph of the "unrestrained knowledge drive," and all that that implies for Nietzsche about the decline of culture? Or rather does it constitute, especially in the case of the research hypertext, a sign of intellectual conscience? Is it the "misuse of knowledge" in the "endless gathering of material" (see note 30)? Or is it rather in the spirit of Nietzsche's paean to physics in The Gay Science, which holds that in order to "become those we are ...we must become the best learners and discovers of everything that is lawful and necessary in the world: we must become physicists in order to be able to be creators"? [36] 2) Internet technology and applications like the research hypertext can potentially have a profoundly democratizing effect on culture and scholarship. For many --the founders of HyperNietzsche included -- this is a good thing, something to be worked toward and encouraged. According to the HyperNietzsche model, this means in the first place the free, worldwide distribution of cultural heritage via the Internet. Beyond that, it means a democratic model for the governance of the associations that design and control research hypertexts. Submissions to the hypertext are evaluated for publication by an Editorial Board, which functions democratically: all members of the Board are eligible to vote on submissions. Furthermore, the Board itself is democratically elected by members of the Association (see above). Both the legal and administrative structures of the HyperNietzsche model as well as its Open Source philosophy are deeply informed by democratic principles. Now, it is well known that Nietzsche himself had deep misgivings about democracy and, more pointedly, about democratic culture. It must be noted, here again, that the position is not unambiguous. To cite just one example, in Human All Too Human Nietzsche writes approvingly of the democratization of Europe, which according to him is effecting a move away from narrow, atavistic nationalism and toward the broader and more refined culture of the "good European" (II, p.292; cf. p.275). So it would be going too far to say that Nietzsche is an enemy of democracy, but he was surely a skeptic and a critic. In a telling aphorism, Nietzsche signals his criticism of democracy even in the context of praising its virtues: "Democratic institutions are quarantine arrangements to combat that ancient pestilence, lust for tyranny: as such they are very useful and very boring." [37] Nietzsche's critique of democracy -- both cultural and political -- is a vast topic, but here we need only indicate a few characteristic features. The word "boring" in the previous quote already suggests one crucial but elusive aspect. While it is clearly meant to read humorously, the word is also freighted. It echoes the aesthetic language used in The Birth of Tragedy, and it points toward Nietzsche's frequent invocation of the concept of "taste" when criticizing modernity. [38] While this mode of critique can at times sound carping or superficial, the stakes are actually quite high, since -- for reasons we cannot go into here -- Nietzsche sees what is "boring" and "in bad taste" about modernity to be symptomatic of nihilism. Moreover, his aesthetic estimation of mass democratic culture is linked to a much broader critique of post-enlightenment modernity and its concomitant Christian morality. Finally, Nietzsche is also concerned about the crushing impact of mass culture on individuality. The argument comes across powerfully in Nietzsche Contra Wagner, where he writes that in a democratic culture "even the most personal conscience is vanquished by the leveling magic of the great number; the neighbor reigns; one becomes a mere neighbor." [39] Nietzsche's critique of modern democratic mass culture contrasts starkly with the ideals that guide projects like HyperNietzsche and with the open source ethos that is so prevalent among new media technicians, artists, and scholars. Again, there is certainly a powerful current in Nietzche's thought that is much more of a piece with the open source mindset. It is embodied in the figure of the "free spirit" and is captured well in the epigram used on the homepage of HyperNietzsche: "To work toward making all good things part of the common good and so that all things may be free to those who are free." [40] Yet to embrace this element in Nietzsche and ignore his critique of democratic culture would be shortsighted. Indeed, the fact that he comprehends and celebrates the virtues of modernity makes his perspective on its vices all the more credible. He is thus an invaluable interlocutor for anyone reflecting on the democratizing potential of Internet technologies. 3. At the beginning of the essay, I argued that Nietzsche was a proto-hypertextualist. He understood and relished non-linear organization and structure. He was subversive, a guerrilla philosopher, "a subterranean man ...who tunnels and mines and undermines." Employing Internet argot, one might say that Nietzsche "lived the rhizome." Given all that, it may be somewhat jarring to also recall that, as he indicates in the 1886 Preface to Human All Too Human, one of his most abiding concerns throughout his career is the problem of the order of rank [das Problem der Rangordnung]." [41] Many of the concerns Nietzsche raises about the nihilism of modernity turn on his notion of the systematic dissipation of the "order of rank." The result, in Nietzsche's language, is the culture of "last men," content with mediocrity, lacking aspiration and goal, a culture above all unmoved by desire. What relevance, if any, does Nietzsche's concern about "rank order" have for thinking about new media culture? Even raising the question in this context risks trivialization; it deserves a much lengthier and detailed treatment than can be given here. Let me therefore emphasize that my remarks aim not to be comprehensive, but rather to open the question and to promote further reflection. On the most superficial level, at least, part of the attraction of hypermedia for many artists and scholars is its constantly shifting, non-hierarchical structure. As fiction writer Shelley Jackson observes about hypertext: "it has no point to make, only clusters of intensities, and one cluster is as central as another, which is to say, not at all. What sometimes substitutes for a center is just a switchpoint, a place from which everything diverges." [42] It is likewise evident from the preceding discussion that HyperNietzsche exploits some of the same characteristics of hypertext. These technical innovations, furthermore, carry over into the way practitioners think about and execute their work. Jackson, for example, comments on how hypertext fiction, if it is to be successful, cannot rely on the "thrust" of "plot" that is the mainstay of the traditional novel. The hypertext author needs to embrace a new structure in which "one cluster is as central as another." Jackson and other hypermedia artists are also experimenting with collective modes of creating new work, combining the efforts of a scattered community that collaborates through electronic means. Similarly, the HyperNietzsche model favors non-hierarchical and rhizomatic structures in the execution of scholarly work and facilitates collective, decentralized projects. In practical terms, a fully developed research hypertext has the potential to level the hierarchical structures of authority that have developed in scholarly institutions. It is easy to overestimate this potential, but it does bear consideration since it will inevitably be realized to some extent at least, and since it promises both advantages and disadvantages. As a concrete example, let us consider the authoritative critical edition. Critical editions come into being through the mediation of, and gain their authority in part from, the academic publishing network. Academic publishers, in turn, rely on the structures of authority operative in the university system to set and maintain standards (and, of course, they simultaneously help to create and sustain those structures through credentialing). Related systems of checks and balances -- the book review, the academic conference, etc. -- also play a role in confirming or modulating the authority of the critical edition. The research hypertext, by both making the original documents available and serving as a venue for the publication of an indefinite number and variety of textual editions and commentaries, can radically alter the status of the authoritative critical edition. The HyperNietzsche project is clearly grappling with this issue, and it proposes a system that retains something of the traditional model in that an Editorial Board must review and approve submissions. Any editions published in HyperNietzsche will therefore bear the imprimatur of the Editorial Board. Yet the governing principle is democratic -- the Board is democratically elected by the members of the Association. What kind of authority will such editions have? Whence would such authority derive? From Nietzsche's perspective, democratic institutions are not reliable sources of value hierarchy and rank order. [43] In "Radiant Textuality," Jerome McGann offers an eloquent and persuasive argument for the broad scale benefits offered by hypermedia to humanities scholarship. His argument on behalf of computerization includes the following: "the cumulative nature of critical and scholarly work can be preserved and self-integrated in ways that far transcend the capabilities of paper-based instruments. Computerization not only vastly increases the amount of accessible information, it enables much greater flexibility in the ways information can be shaped, scaled, and negotiated. This doesn't mean that hierarchies of knowledge will be eliminated, as has been sometimes hoped and sometimes feared. Rather, it means that hierarchies can be determined and need not be determinate. Knowledge can be critically ordered for specific and conscious ends. Under such conditions, what is recondite and what is important, or what is central and what is peripheral, emerge as functions of the critical activity itself and need not stand as given horizons of thought." [44] McGann's argument is compelling and the research hypertext, as we saw above, offers a concrete example of how these potential advantages can be actualized and put into use. Yet the passage from McGann also allows us to pose the Nietzschean question more pointedly. McGann acknowledges that there is already a discussion regarding the potentially leveling impact of computerization on "hierarchies of knowledge," but he dismisses the concern. It is not clear, however, what justifies this dismissal, and it may be that the deeper question has not really been addressed. McGann proposes that "the critical activity itself" will ensure that "hierarchies of knowledge" are not eliminated. Yet these hierarchies depend on, in Nietzsche's language, an order of rank. The hierarchy of knowledge depends on a hierarchy of value, and Nietzsche frequently makes the point that the "critical activity" itself can examine and explain and undermine values, but it cannot create them. The more one understands, the less one is able to praise and condemn, in other words, the less one is able to evaluate, to posit values. The essay "On the Uses and Disadvantages of History for Life," is very clear on this point.[45] Critical activity is indeed "necessary" for "life," but it also undermines all values and therefore, in and of itself, it cannot ensure any hierarchy or order of rank. I do not mean to argue that as scholarship migrates into hypermedia form "hierarchies of knowledge" will necessarily be eliminated. It is not even clear what that would mean. I do think, however, that as cultural endeavor -- including art-making and scholarly inquiry -- becomes increasingly bound up with new media technology, the question of the order of rank becomes more pressing. Also, as I indicated at the beginning, I think that both because of his historical influence and because of the breadth and power of his analysis of the underlying issues, Nietzsche proves to be an invaluable interlocutor for those interested in thinking about the emerging new media culture. Since this is an electronic journal, the reader of the present essay may well be gazing right now at a computer screen, using an application with an inspiring name like "Explorer" or "Netscape." It is the same application one could use, say, to view a newly released web-based hyperfiction or to conduct research at the HyperNietzsche site. Two images from Nietzsche's writing might be applicable here, and I would like to evoke them as a way of concluding. Taken together, they might be called "On the Disadvantages and Advantages of New Media for Life." The first image is of Nietzsche's "last man," whose whole being could perhaps be summed up in one characteristic, which Zarathustra notes repeatedly -- the last man seems always to be blinking: '"What is love? What is creation? What is longing? What is a star?" thus asks the last man, and he blinks.'" [46] Let me set beside this pessimistic image, with all its resonance in an age of screengazing, a counterpart. It comes from the section in The Gay Science titled "The meaning of our cheerfulness":

[1] This paper was originally presented at the Annual Meeting of the American Comparative Literature Association in San Marcos, California (April 2003) on a panel organized by Roderick Coover. I am grateful to the participants for their comments. I would also like to thank Paolo D'Iorio for his suggestions and assistance during the preparation of this paper. [2] Nietzsche did in fact receive a typewriter in 1881, but the machine had mechanical problems and he soon stopped using it. Cf. C. P. Janz, Friedrich Nietzsche: Biographie, II. (Mčnchen/Wien: Carl Hanser, 1978) , 81. At the time of this writing, a picture of Nietzsche's typewriter was available on the Web. [3] Vannevar Bush is often cited as the conceptual father of electronic hypertext. See his prescient article "As We May Think," V. Bush, "As We May Think," The Atlantic Monthly 176 (1945):101-108 . [4] For example: "Against positivism, which halts at phenomena -- 'There are only facts' -- I would say: No, facts is precisely what there is not, only interpretations"; or similarly, "There are no facts, everything is in flux, incomprehensible, elusive", quoted from F. W. Nietzsche, The Will to Power, trans. (New York: Vintage Books, 1968) , p.481, 604 (cf. 540, 616). The most reliable electronic version of Nietzsche's oeuvre in German is Malcom Brown's edition of the Colli-Montinari text, which is currently available (alas, for a fee) at Intelex. The web has no shortage of free English translations, but it is a veritable wild west and for the time being, paper editions are preferable. The ones cited in this paper are easily available and relatively reliable. The number following the citation refers to the number of the aphorism or note in the edition cited, unless specifically noted as a page number. [5] "On Truth and Lie in an Extra-Moral Sense," F. W. Nietzsche, The Portable Nietzsche, trans. W. A. Kaufmann. (New York: Viking Press, 1954) , pp 46-47. The most strident passages about truth, including this one and those in the previous note, are usually to be found in unpublished material. As a rule Nietzsche's published discussions of these issues are more nuanced. I briefly discuss problems related to using unpublished material from Nietzsche, known collectively as his Nachlass, in the in the concluding part of this essay. [6] F. W. Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo, trans. W. A. Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale. (New York: Vintage Books, 1989) , Essay III, p.12. [7] M. Joyce, "Notes toward an Unwritten Non-Linear Electronic Text, "The Ends of Print Culture" (a Work in Progress)," Postmodern Culture 2 (1991): available to MUSE subscribers here. [8] E. B. Loizeaux and N. Fraistat, Reimagining Textuality: Textual Studies in the Late Age of Print. (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 2002) , 7. This collection offers a good overview of the issues and a useful bibliography. [9] See also the discussion of the Ivanhoe Game in J. J. McGann, Radiant Textuality: Literature after the World Wide Web. (New York: Palgrave, 2001) . [10] This protean quality can of course be a blessing or a curse -- or both simultaneously. It is our great fortune that the Iliad and the Odyssey were written down and preserved in a relatively fixed form, and books have proved to be ingenious machines for facilitating and preserving the creation of works of the imagination. I shall take up some of the thornier cultural issued raised by hypertext at the end of this essay. [11] For an introduction to these issues, see Reimagining Textuality, op.cit.. [12] Regarding masks, one thinks of screen names and aliases, for example. Hypertext author Shelley Jackson has exploited the masquerading potential of new media and writes perceptively about its broader implications. See for example, her essay "Stitch Bitch: the patchwork girl". Note also the considerable overlap between the worlds of gaming and new media scholarship. New media artists and theorist often publish in the same venues and attend the same conferences as game designers do; the same person may even play both roles: see, for example, the Ivanhoe Game designed by Jerome McGann and Johanna Drucker. In "The World Without Cybertext," Stuart Moulthrop suggests that games, electronic and otherwise, may provide the "major paradigm" for understanding cybertext. [13] Nietzsche often uses the term "good European" as the embodiment of the cosmopolitan virtues he champions over-against geographical or racial nationalism. See Human, All Too Human I:p.179, 475; Human, All Too Human II: p.87, 215; Ecce Homo, "Why I am so wise": p.3; Beyond Good and Evil: Preface, p.241, 254; The Gay Science: 357. [14] Examples abound. Consider Stuart Moulthrup's remarks regarding "the artist as cognitive insurgent" in "The World Without Hypertext." See also Eric S. Raymond, The Cathedral and the Bazaar. Musings on Linux and Open Source by an Accidental Revolutionary. (London: O'Reilly and Associates, 2001) and Raymond's Homepage; and Andrew Leonard's article in Salon.com,"The Cybercommunist Manifesto" and the ensuing discussion in Slashdot. [15] F. W. Nietzsche, M. Clark, et al., Daybreak : Thoughts on the Prejudices of Morality. (Cambridge, U.K.; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1997), Preface, p.1; F. W. Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo, trans. W. A. Kaufmann and R. J. Hollingdale. (New York: Vintage Books, 1989); Ecce Homo, "Why I am a Destiny," p.1. [16] For more information about the project, see P. D'Iorio, ed.,Hypernietzsche. Modèle d’un Hypertexte Savant sur Internet pour la Recherche en Sciences Humaines. Questions Philosophiques, Problemes Juridiques, Outils Informatiques. (Paris: PUF, 2000) ; P. D'Iorio, "Prinicpes de l'HyperNietzsche," Diogene 49 (2002):77-94 ; and of course, visit the HyperNietzsche website. The website is available in six languages, including English, and contains descriptions of the goals of the project. Nota bene: at the time of this writing, some of the project descriptions on the site are somewhat outdated, and while the present essay describes the goals of the project, many of which have been realized or are soon to be so, much that is described here will not yet be available on the website: http://www.hypernietzsche.org/. [17] In a strict technological sense, Open Source means that the source code for the programming is made freely available to the public for use and modification by anyone. The Open Source Initiative (OSI) explains the basic rationale in the following terms: "When programmers can read, redistribute, and modify the source code for a piece of software, the software evolves. People improve it, people adapt it, people fix bugs." For more on the meaning of the concept in the programming world, see the OSI website. In the arts and sciences, open source has come to mean the free dissemination of primary material and secondary scholarship via the Internet. See the HyperNietzsche FAQs and the links provided by the Nietzsche News Center. To protect the rights of authors while ensuring free worldwide distribution, the HyperNietzsche legal team has developed so-called "copyleft" licenses. More information on these issues is available on the HyperNietzsche website by following the link "What is HyperNietzsche?" [18] For the record, I was invited to begin working on HyperNietzsche in 2001 and have been a collaborator on the project since that time. [19] The demonstration version was prepared in French, so the illustrations will have French menus. The actual HyperNietzsche website will be fully navigable in six languages. [20] Preparing manuscripts for use within a research hypertext is a tricky business. Two particular challenges presented by the Nietzsche material deserve mention: a) Most of Nietzsche's manuscript pages contain series of more or less self-contained notes, many of which do not follow a strict chronological sequence (Nietzsche reused notebooks and even pages, sometimes at long intervals). The note, therefore, is the obvious unit of choice for the hypertext signature system. Yet Nietzsche scholarship has traditionally stopped at the page number as the most specific reference (e.g., NIV3 p.26). A system had to be developed that could identify (and represent graphically) individual notes while also remaining consistent with traditional practice; b) Transcriptions of manuscripts and text reconstructions are most accessible to users if they are in HTML and so can be accessed by web browsers, and they are more flexible and more accessible to external systems (such as metatexts) if they are in TEI-true XML. However, these languages do not allow for sufficient precision in reproducing and representing the manuscripts, and XML is cumbersome to use for philologists trying to encode ultradiplomatic transcriptions. A new language had to be developed (the HyperNietzsche Markup Language -- HNML) from which both HTML and TEI-XML documents could be automatically generated. [21] Figures 6, 7, 8, and 9 are taken from the currently available Version 0.3. [22] Students of Nietzsche may recognize the phrase "philology of the future" as a translation of the sardonic title ("Zukunftsphilologie!") of a scathing attack on Nietzsche's first book, The Birth of Tragedy, written by Ulrich von Wilamowitz-Moellendorff. However, both prior to that review (letter to Deussen, 2 June 1868) and subsequently (for example, in his notes for the unfinished essay "We Philologists", F. Nietzsche, Kritische Studienausgabe, ed. G. Colli and M. Montinari. (Muenchen-Berlin/New York: DTV-de Gruyter, 1988), VIII, 55) Nietzsche himself uses similar terms, referring to the "philology" and the "philologist" of the future, respectively. The philology of the future was a pregnant notion for Nietzsche at the start of his career, and its echo can still be heard in the subtitle of a work he wrote much later, Beyond Good and Evil: Prelude to a Philosophy of the Future. The title of the present essay is meant to reflect the full ambivalence of the phrase as it relates to Nietzsche's life and work. A valuable, engaging discussion of this topic, and my source for the letter to Deussen cited above, is J. Porter, Nietzsche and the Philology of the Future. (Palo Alto: Stanford, 2000), 15 and passim. [23] On open source, see note 16 . [24] F. Nietzsche, Werke. Kritische Gesamtausgabe. (Berlin: de Gruyter, 1967ff.) . [25] Needless to say, looking at a digital facsimile is not the same thing as looking at an original document. Nonetheless, the technology has advanced to the point that a digital copy can be at least as legible as an original, and if the interface is well-designed -- designed in other words for maximal flexibility and manipulability by the user -- and if it includes sufficiently detailed information, the documents can be presented with minimal interpretive interference and in a way that allows the reader to develop a rich and fairly accurate sense of the originals. The relevant point here is that the freely available digital archive substantially improves the readers' basis for evaluating the interpretations of others (transcriptions, critical editions, the editing of notes, exegetical commentaries, etc.) and for developing an independent reading. [26] See, for example, the Dickinson Electronic Archives for a different approach to the same task. [27] This latter is the position taken by Paolo D'Iorio. See, for example, P. D'Iorio, "Prinicpes de l'HyperNietzsche," Diogene 49 (2002):77-94 . [28] It is worth noting that, even if the reading of manuscripts were to become a kind of scholarly prerequisite, this would pertain only to authors for whom manuscripts exist (leaving aside the study of textual transmission, for which manuscripts play a different role). Prior to the 18th century, resources are very limited, and since the advent of word processing, manuscripts have become an endangered species. [29] F. Nietzsche, The Birth of Tragedy, trans. W. Kaufmann. (New York: Vintage, 1977) , p. 18. [30] Ibid., p.7. Corresponding to Nietzsche's pessimism about knowledge is his critique of the optimism, or cheerfulness, of the "Alexandrian", or "theoretical" type. From p.17 of the same work: "It [theoretical cheerfulness] believes that it can correct the world by knowledge, guide life by science, and actually confine the individual within a limited sphere of solvable problems, from which he can cheerfully say to life: "I desire you; you are worth knowing." [31] See for example KSA VII:19[27], available in English: F. W. Nietzsche, Unpublished Writings from the Period of Unfashionable Observations, trans. R. T. Gray. (Stanford, Calif.: Stanford University Press, 1999) 19[27]. Another fragment from this same period focuses attention on scholarly practice: "The misuse of knowledge: in the endless repetition of experiments and gathering of material, when the conclusion can be quickly established on the basis of a few instances. This even occurs in philology: in many cases, the completeness of the materials is superfluous", 19[92]. [32] On the Genealogy of Morals and Ecce Homo, op. cit., Ecce Homo "Untimely Ones," 1. See also the second Meditation, "Schopenhauer as Educator," especially p.6. [33] KSA VII:19[105], for English, see note 30 . [34] Daybreak, op. cit., Preface, p.5. [35] F. Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trans. W. Kaufmann. (New York: Vintage, 1974) , Book I, p.2. [36] Ibid, Book IV, p.335. [37] F. W. Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human : A Book for Free Spirits, trans. R. J. Hollingdale. (Cambridge [Cambridgeshire] ; New York: Cambridge University Press, 1986) , Vol. II p.289. [38] As for example in the final section of the Preface to The Gay Science; he strikes a similar note in his attack on "cultural philistinism" in the second Untimely Meditation. [39] Nietzsche Contra Wagner, "Wagner as a Danger," in F. W. Nietzsche, The Portable Nietzsche, trans. W. A. Kaufmann. (New York: Viking Press, 1954) , p. 666. Cf. in the same book the section "Where I offer objections." [40] Human All Too Human II, p.87. [41] See, for example, a notebook entry from 1884 in which Nietzsche wrote, "In the age of suffrage universal, i.e., when everyone may sit in judgment on everyone and everything, I feel impelled to re-establish order of rank," The Will to Power, op. cit., p.854. [42] Stitch Bitch: the patchwork girl, "Everything at Once." [43] Another Nietzschean concept, the "agon" or "contest," might be relevant here. In an early fragment, Nietzsche writes of how competition is the motivating force in Hellenic art and pedagogy, and that it signals the superiority of the ancients over the moderns in these respects: "Every talent must unfold itself in fighting: that is the command of Hellenic popular pedagogy, whereas modern educators dread nothing more than the unleashing of so-called ambition" (The Portable Nietzsche, op. cit, p.37 (KSA, 789). One response, then, to the "order of rank" question might be that the research hypertext facilitates competition; it makes it much easier for opposing views to fight it out in the open and for the superior interpretation to emerge. [44] Quotation is from the electronic version of "Radiant Textuality"; see also McGann's monograph of the same title, above, note 9 . [45] To cite just one relevant passage from among many, discussing the effect of historical knowledge, Nietzsche writes: "... the historical audit always brings to light so much that is false, crude, inhuman, absurd, violent, that the attitude of pious illusion, in which alone all that wants to live can live, is necessarily dispelled: only with love, however, only surrounded by the shadow of the illusion of love, can man create, that is, only with an unconditional faith in something perfect and righteous," F. Nietzsche, On the Advantage and Disadvantage of History for Life, trans. P. Preuss. (Indianapolis: Hackett, 1980) , p.7, p.39; KSA VII, p. 295. [46] F. W. Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra : A Book for All and None, trans. W. A. Kaufmann. (New York: Penguin, 1978) , Prologue, p.5. [47] The Gay Science, op. cit, p.343. |

||

|

|