Technological Resistance to

Xiaojie Cao |

|

Tool |

Active |

Company |

Technology |

|

TriangleBoy |

2000-2001 |

SafeWeb |

HTTP proxy |

|

Freenet China |

2001-2002 |

DIT |

HTTP proxy |

|

Garden |

2001-2007 |

Garden Networks |

HTTP proxy |

|

DynaWeb |

2002-2006 |

DIT |

HTTP proxy |

|

Garden G2 |

2002-2007 |

Garden Networks |

DNS resolution |

|

UltraSurf |

2002-2007 |

UltraReach |

HTTP proxy |

|

Freegate |

c.a. 2004- |

DIT |

Proxy |

|

Firephoenix |

2006- |

UltraReach/WG |

VPN |

|

GPass |

2006-2009 |

DIT/WG |

VPN |

|

Gtunnel |

2007- |

Garden Networks |

VPN |

Table 1. The First Generation Circumvention Tools Used in Mainland China

SOURCE: Various sources on websites of these tools, news coverage and beyond.

Triangle Boy emerged even earlier than these three tools. It was developed by SafeWeb, a U.S.-based software company which was acquired by Symantec on 15 October 2003 and later stopped support for this tool. This company reportedly not only had a financial relationship with International Broadcasting Bureau (IBB, the parent company of VOA) but was also sponsored by a CIA project to provide anti-censorship software for Chinese netizens (Hughes & Wacker, 2003, pp. 72, 154). However, by the end of 2002, the Triangle Boy project was completely blocked in Mainland China. UltraSurf was launched in 2002 by UltraReach Internet Corporation, a Falun Gong internet company (Ng, 2013, p. 40). It enabled users to circumvent internet censorship and firewalls by using a HTTP proxy server, and also employed encryption protocols for privacy, such as the provision of digital certificates for their products to protect their customers from being cheated by fictitious products.

These tools use two main technologies – proxy servers and VPNs. Proxy servers such as Freegate and Ultrasurf can conceal the physical addresses of users and create anonymity for them. Common types of proxy servers include HTTP proxy, CGI proxy, POP3, FTP, and SOCKS, among others. Alternatively, a VPN can create a private and encrypted channel for the user to communicate with internet servers outside the GFW, and it is “faster, fancier and more elegant” (J. Fallows, 2008) than a proxy server. A slight technological shift exists in the first generation circumvention tools, from proxy servers to VPN (as shown in Table 1). This shift is actually a technological response to the update of the GFW.

The political dimension

Chinese hackers with Falun Gong backgrounds have been very active in programming anti-GFW tools. SafeWeb might not have a direct relationship with Falun Gong; however, the other four organizations, especially DIT, UltraReach Internet Corporation, and World’s Gate, may share some common interests (e.g., as part of Falun Gong organizations) and have a vague relationship with one another. In fact, the companies of Global Information Freedom (GIF), DIT, UltraReach Internet and Garden Networks for Freedom of Information formed a loose alliance in 2006 as the Global Internet Freedom Consortium (GIFC) (GIFC, n.d.). An interesting contradiction on the GIFC website may be good evidence for these companies’ relation with Falun Gong. In a report (GIF, 2007) which announced that it had overcome a temporary setback of increased GFW censorship, GIFC defined the software of FirePhenix and GPass as World’s Gate products; while on its webpage “Our Solutions,” GPass was on the product list of DIT and FirePhoenix of UltraReach Internet Corporation. Although on the websites of these small companies there is no information to publically confirm that, it invites a reasonable inference that DIT, UltraReach Internet Corporation and World’s Gate either have overlapped personnel or belong to the same parent. This suggestion has been supported by other news coverage (Pomfret, 2010), including the assertion that Bill Xia himself is the president of DIT and at the same time a follower of Falun Gong.

It is interesting that most of these small internet companies aimed at creating a freer Chinese internet are physically based in North America (particularly on the West Coast of the U.S., where a huge number of local hackers gather as well). Hacker culture there is relatively more mature and the idea of a free internet has been widely acknowledged there for a long time. For the overseas Chinese dissenters (be they religious or political), such a technology-friendly environment provides plenty of moral and technological resources for their development of anti-censorship software. This, however, does not mean that these dissident Chinese hackers have positive interactions with local Western hackers; conversely and interestingly, they seldom interact with each other at the technical level.[14] The only such interaction publicly available so far has happened in 2012, between Tor and UltraSurf, and it was not a positive interaction but an embarrassing quarrel (see Appelbaum, 2012; Ultrareach Internet Corporation, 2012). Tor checked nine claims by UltraReach and its advocates and found that nine were all “false, incorrect or misleading.” It further pointed out that “it is possible to monitor and block the use of Ultrasurf using commercial off-the-shelf software” and recommended against the use of this tool since “the vulnerabilities presented in this paper are not merely theoretical in nature; they may present life-threatening danger in hostile situations.” UltraReach responded promptly, but insisted that the UltraReach tool was designed according to a different philosophy from that of Tor, and that Tor’s “unsubstantiated attacks” were primarily an attempt to lobby against funding for the UltraReach project.

The quarrel between UltraReach and Tor reveals differing stances between Chinese dissident hackers and their Western counterparts. First, unlike their Western counterparts, Chinese dissident hackers emphasize more on closed-source software rather than F/OSS. Most of the above tools are closed-source, partially due to the tense, fraught relationship between circumvention tools and the GFW. These small companies claim that if these tools were open-source, China could easily update its censorship mechanics accordingly. The price is that these tools often receive critiques (as criticized by Tor in UltraReach’s case) about issues relevant to safety, privacy, security and anonymity; for example, the users may risk being monitored further: maybe not by the Chinese authorities, but by the creators of these tools.[15] pretty diverse bunch“technical orientation” (Coleman, 2011). However, Chinese dissident hackers seem to have utilized hacking activities and circumvention tools purposely as part of their larger religious and/or political agenda. Third, dissident Chinese hackers are bedeviled by ideological contradictions. Although they are against the Chinese authorities, they at the same time try hard to get funds from the U.S. Government and other organizations (Pomfret, 2010).[16] Since the GFW started to censor widely in about 2001, various news organizations such as VOA and RFA that at least partially targeted Asian countries (China in particular), became unavailable in Mainland China. This is the background to the fact that VOA and RFA have since been very active in funding Chinese dissident programmers to develop anti-GFW tools.

From this point of view, first generation circumvention tools are products of a much more organized and centralized movement, and they serve – from a technological perspective – a much larger religious and/or political purpose.

The influence of these tools

These tools are targeted at Mainland Chinese users, but some, such as Freegate, also attract users beyond China and have become popular in other authoritarian states such as Iran and Syria. In 2006, about 100 thousand Chinese netizens were estimated to use circumvention tools such as Freegate, UltraReach and Garden Networks to surf online daily, an estimation made by the creator of Freegate (Bill Xia) and impossible to confirm (Fowler, 2006). Ultrasurf had reportedly gained a population of 80,000 users in Iran, China and Vietnam by the end of April 2011 and in some extreme cases, such as during periods of social unrest in Tunisia and Egypt, the programmers of these tools needed to limit the sharply increased access from these areas to avoid overloading the system (Applebaum, 2011).

However, developers have seldom mentioned the exact number of users of their circumvention products. If they have spoken publically about this, they have been inclined to either use indirect metaphors or to make announcements in a very vague way.[17] The exaggeration of their products’ challenge to the GFW might be explained as a marketing strategy for funding purposes. The majority of Chinese netizens seem to have little interest (if any) in bypassing the GFW, not only because of the financial and political risk of being caught, but also because most of the time, there seems to be no need to do so – entertainment and information within the GFW seem to be enough for their daily needs. Indirect data have explained the low popularity of circumvention tools. For example, a report in 2010 suggested that the tools provided by GIFC were employed by “at most 5 percent of internet users even in places such as China or Iran where the Web is tightly controlled” (Pomfret, 2010). According to a series of four surveys (see Table 2) conducted by the Research Center for Social Development, CASS, the percentage of Chinese netizens who used proxy servers significantly declined over the first decade of this century, particularly between 2003-2007.[18] Anecdotal evidence further suggests that while many Chinese netizens (especially university students) were aware of proxy servers and knew how to use them, the percentage of people using proxy servers daily to access blocked sites was relatively small (Dong, 2012).

|

|

2000 (N/A) |

2003(N=1619) |

2005(N=1165) |

2007(N=1315) |

|

Always |

10.0 |

13.2 |

9.0 |

5.5 |

|

Seldom |

25.0 |

33.2 |

19.7 |

21.0 |

|

Never |

65.0 |

53.6 |

71.2 |

61.4 |

Table 2. Proxy Server Users in Mainland China (%)

SOURCE: Survey report of Internet use and its influence: Beijing, Shanghai, Guangzhou, Chengdu and Changsha (2000)(as cited in MacKinnon, 2008); Surveying Internet Usage and Impact in Twelve Chinese Cities (October, 2003); Surveying Internet usage and impact in five Chinese cities (November 2005) (L. Guo, 2005); Surveying Internet Usage and its Impact in Seven Chinese Cities (November 2007) (L. Guo, 2007, p. 106)

These tools do have some critical impact for a small group of Chinese netizens (citizen journalists, dissidents, activists and public intellectuals in particular). Proxy servers have gained popularity mainly among students and hackers (J. Fallows, 2008). Foreign business, retailers and vendors of technological products, academic institutions, as well as individuals, are the main consumers of VPNs.[19] Users of these tools might increase significantly in extreme cases such as during periods of social unrest and other emergency events (e.g., SARS in 2003) (Elgin & Einhorn, 2006). The diverse usage of these tools has paved the way for the new generation of circumvention tools.

Scattered Hacking: Circumvention 2.0

Hacking resistance functions as a challenge to the Chinese authorities. But similarly to their Western counterparts, Chinese hackers are also far from a monolithic group – they are diverse both in thoughts and in actions. – they are diverse both in thoughts and in actions as well. Since about 2007, a new type of hacking has emerged in Chinese cyberspace. The hackers of this type not only engage in releasing new anti-censorship tools which are widely distributed, various, mixed and dynamic (these tools could be defined as second generation), but also launch scattered, unfocused, individualized, and quotidian attacks towards the censorship machine (the GFW in particular) as revealed by the theory of the hacking movement the Xixiang Jihua (the West-Chamber Project, the WCP).

The West-Chamber Project

The West-Chamber Project, the only anti-GFW hacking project with its main participants physically located in Mainland China so far, started in July 2008 and ended in 2010.[20] The name of this project was provoked by the classic Chinese novel The Story of the Western Wing, within which the hero and heroine are two lovers who climb over the wall and engage in clandestine sexual activity.[21] It metaphorically refers to the software helping ordinary netizens to reach censored materials. This hacking project planned to provide domestic netizens free information and uncensored websites. The announcement for this project reads like this:

As technologists, we need to do something crazy. If we take no action, we will suffer what the bad guys have done. It would be a shame! The GFW becomes mighty and dreadful only because we have not stood together and against it. Now we should stand out and fight; otherwise, we will be mocked in the future by our children who will say “Hey old men, why haven’t you resisted it in the first place?” [my translation] (Development Team tek4, 2008; as cited in GFWREV, 2010c)

The hackers started a blog, GFW Jishu Pinglun (Technical Reviews on the GFW), on an international host server and constantly revealed their hacking activities towards the GFW and their involvement in opposing the Green Dam Youth Escort, and they also covered the history and function of the GFW.[22] The screen names of participating hackers were also published, including tek4, KLZ毕业 (KLZ Graduate), iGFW, nust-, 店长 (Store manager), r007, r008, t00ls, em777, eviloctal, ZWA, Tor project, i2p, and会長 (Chairman).[23] This blog posted its first article with an English title, “Hello World,” on 23 October 2009, and up until 21 March 2010 when the project team was disbanded, a total of thirteen articles were published (with seven articles in 2009 and ten in 2010). These articles have received limited feedback, with the number of responses shifting from nil to over a hundred (some of which are either advertising or meaningless information). But these articles were widely re-posted by other overseas Chinese websites, which increased their general influence.

A new anti-GFW theory

Based on loopholes in the GFW found by previous research (e.g., Clayton, Murdoch, & Watson, 2006), as well as more general research (e.g., Ptacek & Newsham, 1998), the WCP has developed an interesting resistance theory of “shooting at the GFW.” This means generally that the more attacks on the holes in the wall, the easier it is for users to get around this system; moreover, scattered, dynamic, mixed and distributed means are better. Following this theory, the project team tried hard to mobilize more ordinary netizens to participate in activities challenging the GFW.[24] It would be fair to argue that the WCP still might not have been able to mobilize enough netizens, but it seems that they have done much better than Chinese dissident hackers. The reason why Chinese dissident hackers have failed in challenging the GFW (and promote closed-source software rather than open-source software) is that, at least partially, they could not mobilize enough talented netizens to become deeply involved in the hacking process.

There are three dimensions of this resistance theory and its practical approaches. First, niche technological resistance has been applied. Compared to those well-organized, centralized and collective attacks against the censorship machine, niche attacks would have less chance of being felt by the Chinese authorities. The censorship machine of course can easily recognize such attacks, but these scattered and small-scaled attacks might not be worthy of reporting to higher levels of authorities – the censoring instructions come from higher levels of authority and not from the censorship machine itself, which is just an executive body of instructions from the former. With scattered (such as using technology of p2p), small-scaled, various, mixed and dynamic characteristics, the second generation attacks might be tolerated by the system; through tiny and everyday forms of resistance, huge changes may eventually arrive (see GFW Blog, 2009).

Second, the WCP development team believes that the design philosophy of the GFW is that “better is worse.” In other words, the GFW will not try to fill up every loophole in its system; in the contrast, it survives together with these loopholes. The only criterion is to keep both the number and size of the loopholes at an acceptable scale from the perspective of the GFW (and this might be partially because of the funding issue).[25] The team acknowledges that resisters against the GFW, and the GFW itself, have formed an ironic relationship, within which both parties try to maintain a dynamic balance. On the one hand, the GFW seems to have potentially left some room for the tech-savvy to breach the wall; on the other hand, in many situations the anti-GFW resisters have appealed to hackers not to push the wall too hard, and thus could avoid enraging the censors, and decrease the possibility of the entire internet being cut off as their last resort.[26] An ideal dynamic relationship between the GFW and its resisters could be formed if the resisters at the weaker end of the spectrum pretend to be weak and let the GFW become intoxicated with small successes in its blocking activities.

A third dimension of this resistance theory is that, although at the current stage the authorities and the GFW are located at the top of this ecosystem and the ordinary netizens at the bottom, ordinary netizens still can successfully resist their superiors – successful insofar as they access uncensored information whilst avoiding the risk of being caught – by utilizing individualized, scattered means of resistance. According to this theory, the only issue resisters must bear in mind is that there is no way to find a perfect, one-off solution with which to circumvent the GFW, since the GFW itself is continually being updated. Resisters have to keep on learning this system and updating their methods of resistance accordingly. The WCP team concluded its program by calling for more netizens to get involved in the process of challenging the GFW in its last article:

These articles are trying to show a learning process and methods of the GFW as well as an interest of reverse engineering the GFW. Readers like you are better off being not only a receiver of these messages but also a positive thinker and actor. If one out of a hundred people start to think about the GFW issues, one out of a thousand starts to do research about it, and one out of ten thousand starts to make the principals into practice, things might get changed eventually. If all the readers are just passive receivers and engage nothing in challenging this system, the GFW will become even stronger and mightier and that will be a disaster for all of us. [My translation] (GFWREV, 2010b)

The calling for more talented netizens to participate in the resistance towards the GFW has been echoed by other ordinary hackers. For example, a user with the screen name “Laomao” published on his/her blog Wo blog gu wo zai (I blog therefore I am) an article entitled “Guanyu Qiang de Jishu Taolun” (Technical Discussions on Firewall), which invites “those who have interests in programming” to engage with shooting at the technical loopholes of the GFW and eventually put an end to it (see Laomao, n.d.).[27]

Fundamentally speaking, the WCP only tried to point out the loopholes of the GFW and the possibility of taking advantage of these holes; it did not directly produce any new or real circumvention tools. Besides acknowledging the value of existing tools (which are low cost and have shortcomings), it invited more volunteers to focus on technologies of “private SSH and VPN,” since these technologies represent the future of anti-censorship tools. In terms of inviting more netizens to practice the theory of “shooting at the GFW,” the WCP has crucially influenced anti-GFW practices.

New trends of technological resistance

Some first generation circumvention tools are still available in Mainland China, but most of them have been blocked completely by the GFW. Various new tools, partially provoked by the WCP, have been created and circulated since, particularly those tools compatible with smart phone systems (e.g., Android) and other existing programmes.

Fqrouter is one such free anti-GFW tool for Android mobile (smart phone/tablet) users in China. According to its website (fqrouter.com), several public proxies are built into this tool, which can work on mobiles running Android without needing ROOT permission. But when ROOT permission is given, this tool can additionally function as a “router.”[28] The name “fqrouter” combines the acronym of Chinese phrase “fan qiang” (circumvent the firewall) and “router.” Started in 2013 by a hacker with the screen name Qin Fen, this tool utilizes a technology that can theoretically transform any Android mobile running it into a router. Although it may result in slower surfing speeds and require more frequent battery charges, this tool has functioned stably so far, with its longest streak of downtime only lasting 11 days in December 2013. The creator has made clear that while he or she did welcome donations they would not go to the creator’s own pocket but rather to two public host servers (which help to promote this tool). Users are encouraged to report any problem with this tool, to circulate it as widely as possible and, most importantly, to contribute with their source code (see fqrouter, 2013). A virtual discussion group for this tool has since been set up at Baidu Tieba, a popular BBS service hosted by Baidu. It is interesting that this kind of discussion of anti-censorship measures could be tolerated by the censors.[29] At the time of writing, there have been 18,375 followers and 42,182 individual posts in this group (Baidu Tieba, n.d.).

Another tool, fengye xiangjiao (the Maplebanana-proxy), which is also known as the Onion-project or Smartbanana, was developed by an anonymous hacker named “ring-hacker” (see Onion-project: fengye xiangjiao, 2013). This tool simplifies the codes of GoAgent, Wallproxy and Gsnova, and makes these circumvention tools more compatible with the open-source browser Firefox. So too do many others including VPN Gate (designed by Japanese researchers and targeted mainly at Chinese netizens, see Nobori & Shinjo, 2014), GoAgent, Shadowsocks, landing (Lantern), Gfanqiang (not updated since 2013), and Greatagent (originally named Wwqgtxx-goagent) which have also become available for ordinary Chinese netizens.

Tools like these reveal some new trends in technological resistance in Chinese cyberspace. Firstly, while organized means and activities of technological resistance may still exist, scattered, individualized and decentralized means and activities have become relatively more popular. Secondly, the second generation tools are more likely to be open source, and their users may contribute to the source code as well. Thirdly, these new tools are potentially designed for solving the problems of existing third-party programmes and are compatible with such programmes (as revealed by the aforementioned tool of Maplebanana-proxy). Fourthly, these new tools are more likely to be made using cheap and readily accessible technology, and hackers themselves do not seem worried about funding (as was the case with dissident hackers of the first generation). Fifthly, most of the second generation tools are originally developed by a single hacker rather than a group of hackers (though in some cases volunteer hackers may be involved in the process later on), and they develop these tools “simply and purely” based on their interests. Last but not least, besides using various social networking platforms, such as Facebook, Twitter, and YouTube, to circulate their products, these hackers may also use more centralized platforms, such as Beauty Garden (Meiboyuan, allinfa.com) and the Project Hosting of Google Code (which aims at “providing a free collaborative development environment for open source projects”), to discuss anti-censorship issues and develop tools. These platforms (most of which are outside the GFW) have become virtual homes for hackers.

In general, many hackers of the new generation, including the team of the WCP, tend to believe that technological resistance against the GFW is an ongoing struggle, for while the GFW is very good at attacking resistant tools, ordinary netizensmust keep on adapting new methods to get around the firewall. The main problem of this model of imbalanced interaction between resisters and censors lies in the fact that as the GFW becomes mightier and stronger, it will become technologically and economically harder for netizens to break through the wall. This worry becomes even more significant in light of two increasingly common viewpoints. One is that “You might think you have successfully broken through the wall, while in fact you are still in the wall” (Yu Zhou, Duan, & Li, 2010) and the other is that “Our difficulty is not that wall but the decreasing number of users of circumvention tools” (Diao, 2014). Hackers could undoubtedly find ways to adapt themselves to this system, but it is part of a much larger problem that technological methods alone – circumvention tools included – cannot fix.

Conclusion

Technological resistance in Chinese cyberspace has undergone a nuance shift from organized, centralized and collective to much more scattered, small-scale, low-profile and quotidian. Such resistance does function as a challenge to the GFW control system,and enables users to access and share freer information. However, we should not overstate the influence of such resistance. First, though ordinary netizens may also involve in technological resistance (by means of such as becoming consumers of circumvention tools), this kind of resistance is mainly conducted by a small group of tech-savvy netizens. Second, there is no sign of the GFW becoming less powerful; by contrast, it seems to be more powerful than before. The second generation hackers strategically launch scattered, small-scale, low-profile and quotidian attacks and tools to challenge the GFW system – which is impossible, to date, for the GFW to block completely. At the same time, however, they try to avoid enraging the censors and emphasize theirco-existence with this control system – which determines that such small-scale, scattered resistance may not be able to fundamentally challenge this system. From this point of view, this new kind of resistance seems to have become a part – albeit an unharmonious part – of the authoritarian control system.

References

Applebaum, A. (2011, 4 April). Why has the State Department run into a firewall on Internet freedom?, The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/opinions/why-has-the-state-department-run-into-a-firewall-on-internet-freedom/2011/04/03/AFYnn9eC_story.html

Baidu Tieba. (n.d.). fqrouter ba [The forum on fqrouter]. [Baidu Tieba post] Retrieved 23 April, 2015, from http://tieba.baidu.com/f?kw=fqrouter&ie=utf-8&pn=0

Barme, G. R., & Ye, S. (1997, June). The Great Firewall of China. Wired, 5.06, 138-149.

Beech, H. (2013). China's red hackers: The tale of one patriotic cyberwarrior. Time. Retrieved from http://world.time.com/2013/02/21/chinas-red-hackers-the-tale-of-one-patriotic-cyberwarrior/

Biancheng Suixiang. (2010, 10 March). "Ruhe fanqiang" xilie: Ziyoumen - TOR beifeng zhihou de lingyige xuanze [Series articles on "How to breaching the GFW:" Freegate - an alternative after Tor being banned]. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://program-think.blogspot.com/2010/03/choose-free-gate.html

Biancheng Suixiang. (2012, 15 June). "Ruhe fanqiang" xilie: Jiandan saomang I2P de shiyong [Series articles on "How to breaching the GFW:" Simply eliminate illiteracy of using I2P]. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://program-think.blogspot.com/2012/06/gfw-i2p.html

Biancheng Suixiang. (2014, 31 July). "Ruhe fanqiang" xilie: fqrouter - anzhuo xitong fanqiang liqi (mian ROOT) [Series articles on "How to breaching the GFW:" fqrouter - a Android-based wonderful tool for breaching the GFW without ROOT permission]. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://program-think.blogspot.com/2014/07/gfw-fqrouter.html

Coleman, B. (2013). Embracing expertise. Concurring Oppinions. Retrieved from http://concurringopinions.com/archives/2013/09/embracing-expertise.html

Coleman, G. (2011). Hacker politics and publics. Public Culture, 23(3), 511-516.

Coleman, G. (2014). Hacker, hoaxer, whistleblower, spy: The story of Anonymous. London: Verso.

Cuthbertson, A. (2014). Hong Kong protests: Anonymous hackers leak Chinese government data, shutdown websites. International Business Times. Retrieved from http://www.ibtimes.co.uk/hong-kong-protests-anonymous-leaks-chinese-government-data-1469747

Daily Herald Tribune. (2008). The Great Firewall of China - Psiphon, Tor two ways to circumvent Internet censorship. Retrieved from http://www.dailyheraldtribune.com/2008/08/22/the-great-firewall-of-china-psiphon-tor-two-ways-to-circumvent-internet-censorship

DIT. (n.d.). Mass Mailing Retrieved 26 October, 2014, from http://dit-inc.us/mass_mailing.html

Elgin, B., & Einhorn, B. (2006). Outrunning China's web cops. Bloomberg Business Week. Retrieved from http://www.businessweek.com/stories/2006-02-19/outrunning-chinas-web-cops

Epstein, G. (2013, 6 April). China and the internet: A giant cage. The Economist, 1-14.

Fallows, D. (2008). Most Chinese say they approve of government Internet control. Pew Internet & American Life Project. Retrieved from http://www.pewinternet.org/files/old-media/Files/Reports/2008/PIP_China_Internet_2008.pdf.pdf

Fallows, J. (2008). The connection has been reset. Atlantic Monthly, 301(2), 19.

Fowler, G. A. (2006). Great Firewall: Chinese censors of Internet face "hacktivists" in U.S. The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved from http://online.wsj.com/articles/SB113979965346572150

fqrouter. (2013, 24 July). fqrouter shi mianfei de, na wo neng zuoshenme? [Since fqrouter is a free tool, what can we contribute to it?] Retrieved 2 November, 2014, from http://fqrouter.tumblr.com/post/56329233855/fqrouter

GFW Blog. (2009, 30 August). Yuehou jifen: GFW [Burn after reading: GFW]. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.chinagfw.org/2009/08/gfw_30.html

GFWREV. (2010a, 18 February). Ping yitiao duzhe liuyan [Comment on a response from a reader] [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://gfwrev.blogspot.co.nz/2010/02/blog-post.html

GFWREV. (2010b, 21 March). Shenru lijie GFW: Jielun [A deep understanding of GFW: Conclusion]. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://gfwrev.blogspot.co.nz/2010/03/gfw.html

GFWREV. (2010c, 10 March). Xixiang Jihua [West-chamber Project]. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.gfwrev.blogspot.co.nz/2010/03/blog-post.html

GIFC. (n.d.). Our solutions. Retrieved from http://www.internetfreedom.org/zh-hans/node/33

Guo, L. (2015, 22 April). [personal communication].

Henderson, S. J. (2007). The dark visitor: Inside the world of Chinese hackers. (n.p.): Lulu. com.

Huanqiu Shibao [the Global Times]. (2011). Great Firewall father speaks out. Sina. Retrieved from http://english.sina.com/china/p/2011/0217/360409.html

Hvistendahl, M. (2010). China's hacker army. Foreign Policy. Retrieved from http://foreignpolicy.com/2010/03/03/chinas-hacker-army/

Laomao. (n.d.). Guanyu qiang de jishu taolun [Technical review on the GFW]. [Blog post]. Retrieved from http://www.chinagfw.org/2008/08/blog-post_725.html

Lemon, S., & Gohring, N. (2006). Researchers find "Great Firewall of China" workaround. InfoWorld. Retrieved from http://www.infoworld.com/article/2658302/security/researchers-find--great-firewall-of-china--workaround.html

Norton, Q. (2012). How Anonymous picks targets, launches attacks, and takes powerful organizations down. The Wired. Retrieved from http://www.wired.com/2012/07/ff_anonymous/all/

Onion-project: fengye xiangjiao. (2013). Retrieved from http://allinfa.com/onion-project-20130228.html

Ownby, D. (2008). Falun Gong and the future of China. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

People's Daily Online. (2002). Chinese satellite TV hijacked by Falun Gong cult. Retrieved from http://en.people.cn/200207/08/eng20020708_99347.shtml

Perez, S. (2015). GitHub continues to face evolving DDoS attack. Tech Crunch. Retrieved from http://techcrunch.com/2015/03/30/github-continues-to-face-evolving-ddos-attack/

Pomfret, J. (2010, 12 May). U.S. risks China's ire with decision to fund software maker tied to Falun Gong, The Washington Post. Retrieved from http://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-dyn/content/article/2010/05/11/AR2010051105154_pf.html

Su, X. (2012, 6 June). "Fanqiang" xu jinshen, "chuxian" hen rongyi [Be careful of "bypassing the wall" since it's easy to be "out of line"], Shandong Fazhibao [Shandong Legal News]. Retrieved from http://fazhi.dzwww.com/dj/201206/t20120606_7607297.htm?from=timeline&isappinstalled=0

Ultrareach Internet Corporation. (2012). Tor's critique of Ultrasurf: A reply from the Ultrasurf developers. Retrieved from http://ultrasurf.us/Ultrasurf-response-to-Tor-definitive-review.pdf

Walker, P. (2011). Cyber-hacking: prolonged series of attacks by one country uncovered. The Guardian. Retrieved from http://www.theguardian.com/technology/2011/aug/03/china-cyber-hacking-campaign

WikiLeaks (Cartographer). (n.d.). Spy files. Retrieved from https://www.wikileaks.org/spyfiles/map/

Xia, B. (2008). Cat and mouse. Index on Censorship, 37(2), 114-119.

Ye, Y. (2014, 25 September). Jingti didui shili jie waizikonggu xiang wo anquan lingyu shentou [Be alert to hostile forces to get involved in our security realm via foreign share holding], Zhongguo Guofangbao [China National Defense News]. Retrieved from http://www.hswh.org.cn/wzzx/llyd/aq/2014-09-25/28176.html

[1] Xiaojie Cao is a PhD candidate in Media, Film and Television of the School of Social Sciences at the University of Auckland. His current research interests lie in cyberculture, internet governance, Chinese internet, censorship and resistance. He can be contacted via email (xcao024@aucklanduni.ac.nz). The author thanks Dr Luke Goode for his comments on the draft paper. Two anonymous reviewers, editors of this issue, as well as Dr Jonathan Lillie, have provided valuable feedback.

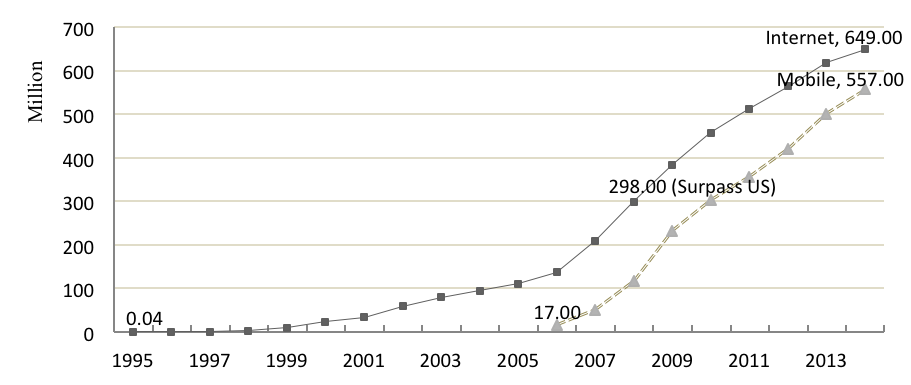

[2] The question of the exact time of China’s first connection to the internet remains open. Some scholars argue that the starting time was in 1993 (Kalathil & Boas, 2010), others argue that China first established a connection to the internet in April 1994 and about 23,000 Chinese were estimated to have restricted internet access at that time, all government officials and select academics (R. J. Deibert, 2002; MacKinnon, 2008). Here I choose 1995 as the time when ordinary Chinese people were allowed to go online, which has been confirmed by other resources such as J. L. Qiu (2004).

[3] In the early days of the internet development, for those who could not financially afford personal computers, internet bars became a good alternative (Yongming Zhou, 2008). A computer in later 1990s China could cost $1,000-1,200 dollars. An ordinary family earned only around $600 dollars per year at that time (according to 1996 government figures); furthermore, in 1999, the monthly cost for an internet connection (totalling 60 hours) was about $29 dollars, plus the phone line connection fee which was 50 cents per hour (cited from Collings, 2001, pp. 192-193).

[4] Building on the Great Wall of China started twenty-eight centuries ago. After several dynasties’ reinforcement, it finally became a defensive shield of stone and brick snaking forty-five hundred miles across the tops of mountains along the northern border of China. Designed to help keep out Mongol and other invaders, it functioned successfully for many years and then became nothing more than a symbol. It is commonly agreed by scholars of the Chinese internet that the concept of the Great Firewall of China (GFW) originated in Geremie Barme and Sang Ye’s article (1997), according to which the project of the GFW started in 1996. This date is confirmed by Thornton (2010, p. 180), though some suggest 1995 as the starting year of this programme (R. J. Deibert, 2002).

[5] But according to an official interview with Fang Binxing in 2011 by Global Times, a Beijing-based nationalist tabloid which is affiliated to People’s Daily, the GFW project was officially claimed to be launched in 1998 and it was not until 2003 that it really started. This same interview also mentions that Fang used six VPNs on his computer at home, by which he could test the GFW system, and notes that what happened between the GFW and the VPNs is “an ageless war” (Huanqiu Shibao [the Global Times], 2011).

[6] As discussed later, much anti-GFW software would be blocked by the GFW (sometimes) shortly after its invention and circulation. For example, some anti-GFW programmers believe that the GFW has employed a group of human censors to collect the updated information of TOR’s bridges from its official websites so that the GFW is able to block TOR promptly (see Biancheng Suixiang, 2012).

[7] From Biella Coleman’s perspective, hacking is “the weapon of the geek” (a utilization of James Scott’s concept of “weapons of the weak,” see Scott, 1985) and hackers “don’t necessarily have class-consciousness, though some certainly do, but they all tend to have craft consciousness” (B. Coleman, 2013).

[8] Some circumvention tools are even circulated among foreigners via USB drive. For example, in 2008, a group of German programmers reportedly created what they call the Freedom Stick, a self-contained version of the Tor browser on a USB drive that the group distributed to German journalists heading to the Beijing Olympic Games (Daily Herald Tribune, 2008).

[9] Fangong Heike is physically located outside Mainland China. It not only hosts a website (www.fangongheike.com) and archives its hacking activities in Mainland China on it, but also forms virtual communities on social networking sites such as Twitter (twitter.com/fangongheike).

[10] In 2009, Chinese authorities declared that all new computers sold after 1 July 2009 should have pre-installed the filtering software called Green Dam Youth Escort or the setup files on an accompanying compact disc. This software was claimed to filter out pornographic images and violent information and thus could protect youth from harmful content; however, it was soon widely suspected that this was nothing more than a new way of monitoring individual user performance (Faris, Roberts, & Wang, 2009). This mandatory act was ultimately unsuccessful (R. Deibert, Palfrey, Rohozinski, Zittrain, & Haraszti, 2010, p. 278).

[11] Falun Gong has claimed to be resistant to Chinese censorship, but it is ironic that in the first place, when this group received criticism from its opponents, it “urged the Chinese government to use its powers of censorship to muzzle the opponents” (Zhao, 2003, p. 215).

[12] Information comes from the introduction of these products on the website of GIFC. GIFC has a close relationship with some U.S. officials, with the help of who it receives funds from the U.S. government (see MacKinnon, 2012, pp. 188-191). From a technological perspective, Freegate has a significant update which can enable those who share sensitive information through emails by simply attaching it in the email and the email will be encrypted automatically; once the email is successfully sent out, the user just needs to click a button and the trace of usage will be cleaned immediately.

[13] For instance, its latest success in mass mailing, which was selectively shown on its website, happened in 2005 (ten years ago!). DIT expressed pride because its mass mailing project was mentioned in a testimony for U.S.-China Economic and Security Review Commission on April 14, 2005 – “We send millions of emails a day, and the response has been overwhelmingly positive to the VOA and RFA language services - news summaries and information on local Chinese and international news.” (DIT, n.d.) DynaWeb has encountered a similar fate: although it was not officially denounced, the fact that its latest updated was done on 15 April 2005 shows that the report that DynaWeb was blocked by Chinese authorities in May 2006 should be somewhat convincing.

[14] Some dissident Chinese hackers such Bill Xia may talk about the GFW and internet censorship in China via media outlets, or publish relevant academic articles. But publically available data shows that they seldom interact with local Western hackers at the technical level.

[15] According to the Spy Files leaked by WikiLeaks, 32 companies (including UltraReach Internet Corporation) of the U.S. have been involved (WikiLeaks, n.d.). This invited a wide scepticism among Chinese users that using the tools created by this company could reportedly create the risk of being monitored.

[16] To fund U.S. efforts in support of Internet freedom, Congress in the 2008 financial year appropriated $15 million, most of which has been spent or is obligated. Another $5 million was appropriated in the 2009 financial year. Finally, Secretary Clinton’s January 21 speech mentioned an additional $15 million for the 2010 financial year. The U.S. Broadcasting Board of Governors’ International Broadcasting Bureau also supports counter-censorship technologies and has committed approximately $2 million per year to help enable internet users in repressive regimes to have access to the VOA and other U.S. governmental and non-governmental websites and to receive VOA email newsletters (Figliola, Nakamura, Addis, & Lum, 2010). An ironic fact is that some American technology companies such as Cisco, at the same time, have been busy selling censorship technologies and products to the Chinese authorities (Burkart, 2014; Nobori & Shinjo, 2014).

[17] Such as at the end of Bill Xia’s essay about China’s internet censorship (2008), which implies with the metaphor of “cat and mouse” that “2008 is the year of the Rat in the Chinese lunar calendar, so things are looking pretty good for a little rodent that chews holes in walls; 2010 will be the year of the Tiger. There is no year of the Cat in the Chinese zodiac system” (p.119). On the “About” page of DynaWeb, it says things such as: “DynaWeb was launched in March 2002 and visitors have been increasing ever since then. Access log shows that more than 90% of visitors are from China directly or through proxy.” And UltraSurf describes itself like this: “Originally created to help internet users in China find security and freedom online, Ultrasurf has now become one of the world's most popular anti-censorship, pro-privacy software, with millions of people using it to bypass internet censorship and protect their online privacy.” Even some ordinary users themselves have realized the bias of Falun Gong’s website such as that “Many news/comments on that website are not objective, only Opposition for the Sake of Opposition” (see Biancheng Suixiang, 2010).

[18] It needs to be noted that, in the original sources, figures for 2005 and 2007 do not add up to 100%. I emailed the corresponding author Guo Liang for some clarifications and he replied that it was because of some “missing data” (since participants might refuse to answer relevant questions, which was quite common in surveys) (L. Guo, 2015). Particularly in 2007, the figure added up only to 87.9%, so the finding that 5.5% netizens “always” use proxy server may not as credible as that in previous surveys. The other issues is that, since the entire population of Chinese netizens has undergone significant increase over the last two decades (22.5 million, 79.5 million, 111 million and 210 million respectively in 2000, 2003, 2005 and 2007) (CNNIC, 1997-2015), the exact population of proxy server may have increased (2.25 million, 10.494 million, 9.99 million and 11.55 million respectively in the above years). We should note that this table does not suggest anything about the user population of the second generation circumvention tools (which issue will be discussed later).

[19] Scholars may apply VPNs to update their databases of recent international research in their fields, particularly since Google Scholar became unavailable within the GFW. VPNs are somewhat tolerated by the Chinese authorities, and this could be understood as part of the strategies of resilient control. VPNs are very cheap in China, and cost only about $40 per year in 2008 (J. Fallows, 2008). Other resources show that on Taobao.com, various circumvention tools have been sold, some of which are as cheap as ¥10 per month (less than $2 dollars) (Su, 2012). However, Taobao seems to have forbidden the selling of VPNs on its platform, since search keywords of “VPN”on its website elicit the response that, “According to the relevant laws, regulations and policies, the results of this search cannot be displayed.”

[20] It ended not due to censorship reasons but as planned. The Development Team did not plan to exist for long, and it ended when the tasks had been finished. “For the tek4 team, there is no continual plan to go on with this programme, neither is plan to data migration. Any development continued and migrated belongs to all others who are interested in it.” My translation. For the original text, see (GFWREV, 2010b).

[21] This book was written by the Chinese writer Shifu Wang (1260-1316). Part of it was first translated as “The Romance of the Western Chamber” by George T. Candlin in 1898; in other English translations it is variously entitled “The Romance of the Western Bower” or “The Story of the Western Wing.” Here I use the translation of “West-Chamber” which was originally used by the hackers of this project.

[22] Its website seems to change according to the surfer’s physical location. For example, I accessed it on 31 October 2014 in New Zealand, its websites shows with a domain suffix of “co.nz” (www.gfwrev.blogspot.co.nz); while if accessed elsewhere, it might change accordingly to a new one.

[23] Screen names reveal something (such as interests, favours, aesthetics or identities) about the hackers. While there is no way to get in touch with these hackers to confirm, we can interpret them as: 1) “tek4” might have something to do with the tools of Ryobi Tek4; 2) the “KLZ” in KLZ Graduate is a common phrase used in the game World of Warcraft; 3) iGFW might refer to a Chinese hacking website (igfw.net), and with “i” meaning “love” in Chinese, iGFW thus ironically means “love GFW;” 4) “nust-” could be understood as the acronym of Nanjing University of Science and Technology (a Chinese university); 5) “eviloctal” refers to a self-claimed grassroots website (forum.eviloctal.com); and 6) “Tor project” and “i2p” are two foreign circumvention tools.

[24] On its blog, suggestions are given to ordinary netizens who encounter problems with internet connection (e.g., internet being entirely cut off, slow surfing speeds which have been technologically manipulated by the censors) as follows: 1) Learn how to use the 56K phone modem and get connected even when the entire internet is cut off; 2) update one’s knowledge of dial-up network from various telnet forums; 3) learn how to connect with satellite internet and update one’s knowledge of this technology; 4) those who are physically located in Shenzhen could think about how to become connected with Hong Kong via technologies of microwave communication and/or atmospheric laser communication – using whatever means possible to set up international communications gateways – and so on (GFWREV, 2010a).

[26] In 2009 after a riot in Xinjiang Autonomous Region (in Northwest China), the internet there was shut off for almost a year. Only some websites of official news portals and governments could be accessed during this period of time. And in March 2012, when social media carried rumours of an attempted coup in Beijing, the government temporarily shut down some of the internet’s micro-blogging services and detained six people (Epstein, 2013).

[27] This article, together with his/her blog, is not accessible at the time of writing; however it has been re-blogged by other hackers’ virtual communities such as the “GFW BLOG.” (see Laomao, n.d.)

[28] According to fqrouter’s website, being a “router” means that not only the Android mobile running fqrouter is able to access restricted websites, but also this mobile can “share” the free internet to other devices. There are a number of ways to share free internet to other devices via fqrouter: 1) WiFi in => fqrouter => WiFi out (i.e. WiFi repeater); 2) Pick & Play; 3) 3G in => fqrouter => WiFi out (Android built-in); 4) 3G/WiFi in => fqrouter => usb out (Android built-in); 5) 3G/WiFi in => fqrouter => Bluetooth out (Android built-in); 6) LAN in => fqrouter => WiFi out (some set-top box). Be noted that WiFi repeater is a unique feature, but it requires hardware/driver support; Pick & Play scan the devices in your LAN, and forge the default gateway to redirect their traffic via fqrouter. Another article about this tool is available at Biancheng Suixiang (2014).

[29] Again, as argued in the previous section, this may be because of scattered and individualized resistance is much more tolerable for the authorities.