| |

The Promise and Perils of

UltraViolet© Technology

Michael Johnson Jr., PhD (bio)

Washington State University

Abstract

This research critically investigates the UltraViolet© technology and argues that this technology offers consumers a form of conspicuous consumption that endorses a culturally important type of commodity fetishism. Unlike P2P exchange of files, or locally streaming content, or even DVD ownership, UltraViolet™ technology attempts to emulate the successes of all three areas of media use without drawing attention to the socioeconomic consequences that adoption of its model endorses. It demands that consumers participate in an economic exchange of capital that requires (1) the purchase of legally “sanctioned media”; (2) pay for its licensure validation process to confirm one’s ownership rights and also (3) purchase access to the very content that consumers already own. UltraViolet™ accomplishes this under a marketing rhetoric of liberating users from the constraints of physical media like Blu-Ray discs by espousing the portability and utility of an all-digital, streaming model of viewer consumption. To evaluate these claims, this research pursues a political economic analysis of this technology that examines these exchanges of capital and the emerging consumption model with its attendant cultural costs for contemporary consumers of digital entertainment.

Introduction

A substantial body of research has been conducted and published about the proliferation of digitized TV and film content circulating throughout the media industry during the post-network era. Some scholars argue that this evolution presages new and revolutionary ways of viewing and consuming these media commodities (Kompare, 2006; Newman, 2012; Vaidhyanathan, 2001; Dixon, 2013; Rifkin, 2001). At least one researcher has argued that these technological evolutions presents some problems that challenge our collectively held, and traditionally understood notions of what constitutes “ownership” in an increasingly digitized world (Striphas, 2006). And Alisa Perren argues that “notwithstanding the industry’s rhetoric about the decline of physical media…distribution practices have substantive material consequences” (2013, p. 170). The rise of subscription based models of streaming media (e.g. Netflix and digital

libraries (like iTunes, Amazon Instant Video etc.) combined with increasing consumer experimentation with and reliability of cloud-based storage, has resulted in Hollywood studios rapidly losing their

traditional, primary sources of revenue. Thus this technological evolution has

rendered the evolving collection of digital content significantly more

important to consumers, content producers (like Hollywood) and society at

large. The popularity of the internet as a method of digital delivery has been

well established in the literature as appealing to a wide array of consumer

demographics – especially amongst younger aged consumers (Matthews

& Schrum, 2003).

The conspicuous consumption

practices of culturally “elite” consumers[1] for

whom the collection of digital media is central, becomes particularly important

for future analyses of commodity fetishism to the larger systems of economic

and cultural production in the United States. The rapidly changing

technological advancements like UltraViolet, which are created

to encourage and regulate consumer enthusiast’s purchase and collection of

digital goods must be analyzed with an explicit attention to the sociocultural circumstances

of their consumption. And such analyses should equally attend to the economic

profitability models that are associated with the accumulation of these digital

goods. As James Kendrick points out, these consumers have historically taken

full advantage of the developments of technologies like UltraViolet “to assert control over their media consumption” in ways

that resonate with them personally (2005, p. 59). Thus, it is the intention of this research

to analyze the ways in which UltraViolet technology functions

with attention to the promises that it makes to consumers and the many pitfalls

that accompany its implementation. To that end, I argue that this technology offers

consumers a form of conspicuous consumption that endorses a culturally

important type of commodity fetishism that obfuscates the socioeconomic

consequences of its adoption. To accomplish this analysis, I look to the

marketing rhetoric of portability, liberation, durability, permanency and

interoperability that its creators communicate to enthusiasts of digital

consumer goods.

Methodology

For the purposes of this research I adopt Jonathan Gray’s argument of

interpreting popular telenarratives and film as

“entertainment” commodities, given the ways in which UltraViolettechnology is both

branded by its creators and marketed to consumers(2010). I employ a mixed

methodology that uses both textual and political economic analysis. The use of textual

analysis focused on discursive forces present in a

text is an important means of understanding how individuals and society

constitute themselves and make sense of the larger world in which they live.

Textual analysis can usefully interrogate how mass mediated commodities create

identities and "construct authoritative truths" (Saukko, 2003) for those who use

(or are represented as using) them, thereby illuminating the participatory (or

non-participatory) role social actors possess in the creation, reflection and

consumption of those truths. The multiple interpretations of a given “text”

frequently look different when examined in relation to other texts or social sensibilities,

thus the task of analysis is not to ascertain the most correct but rather to explore some of the possible and

undiscovered interpretations embedded in the targets of textual analysis. This

proposition is especially applicable

in the study of mass mediated commodities which engender strong feelings

through images and sound that invite the reader to ‘feel and feel’ and

thereby, feel in touch with the real(Saukko, 2003,

p. 109).

This research examines a wide array of

“texts” which include (1) printed and web literature promulgated and

disseminated by the DECE consortium

as well as (2) the larger constellation of

entertainment commodities included and excluded by (3) UltraViolet

technologies to date. To that end, I

utilize textual analysis to examine the method by which these three category of

“texts” gain social value over time, through their conspicuous consumption by

social consumers. Necessary to that examination is an investigation that

determines the degree to which viewers consume mass mediated commodities

produced in a corporatized process of production that

"technologically" and "commercially" constrains content

through the regulatory imposition of UltraViolet

model.

As T.V.

Reed points out, “Whatever else popular culture may be, it is deeply

embedded in capitalist, for-profit mass production" (2011).

The strength of

textual analysis lies in its ability to expose the (1) discourses through which

texts (construed broadly) communicate their message, (2) the sociopolitical

contexts by which those messages are situated or mediated, and the (3) lived

experiences these messages attempt to represent or replicate. While attempting

to get to the "truth” of a particular target, textual analysis facilitates

multiple, multidimensional, nuanced, and tentative ways of understanding while

frequently employing deconstructive techniques which expose the

"historicity, political investments, omissions and blind spots" (Saukko, 2003) of social truths

which are understood as possessing their own continuously contested, but often

tightly regulated possibilities.

This

paper’s political economic analysis “examines how methods of distributing

information and other resources give rise to or undermine different forms of… social relations” (Steirer,

2014, p. 7).

This research attempts to avoid what Kembrew McLeod says are “studies that employ a purely political economic

analysis [that] do not examine cultural practices to any great extent” and

through that omission fail to discern the ways in which cultural practices

create “a whole new set of questions” (2001, p. 6). One of those

questions that my mixed methodology attempts to answer is the ways in which consumer social

relationships to digital commodities work in tandem with evolving conceptions

of socioeconomic value. And as Gregory Steirer notes, “The market for digital film and television, like all

markets involving some degree of genuine competition, can and thus should be

viewed as a social process – or if you will, a wide scale and perpetual

conversation about value” (2014, p. 11).

What Is

UltraViolet?

In

2011 the Digital Entertainment Content Ecosystem or DECE[2]

launched UltraViolet,

a new “digital media ecosystem” that sought to both standardize and vitalize

the electronic sell through market for Hollywood products by offering consumers

their ‘movies and television in the cloud’…since that time the technology

“remains largely unknown to a substantial portion of its target consumers” (Steirer,

2014, p. 2).

In January 2013, more than a full year after the launch, a promotional survey

conducted by Sony Pictures in the US Found that slightly less than half of all

home entertainment consumers were still unaware of the ecosystem (Steirer,

2014, p. 2).

Despite these problems of visibility and technological

acceptance, the official UltraViolet website…defines

it as a “free cloud-based digital rights collection” (UltraViolet

2013).Essentially, it is a type of

“digital rights authentication and cloud based distribution system” that

functions by authorizing and distributing electronic tokens obtained by

consumers to “provide their owners with access rights to individual films or

television episodes”. It is simultaneously a (1)

DVD and Blu-Ray disc level DRM encryption technology, (2) a set of technological standards

for device manufacturers and software app developers as well as (3) a web-based

“library” portal where consumers can access digital versions of their

entertainment content.

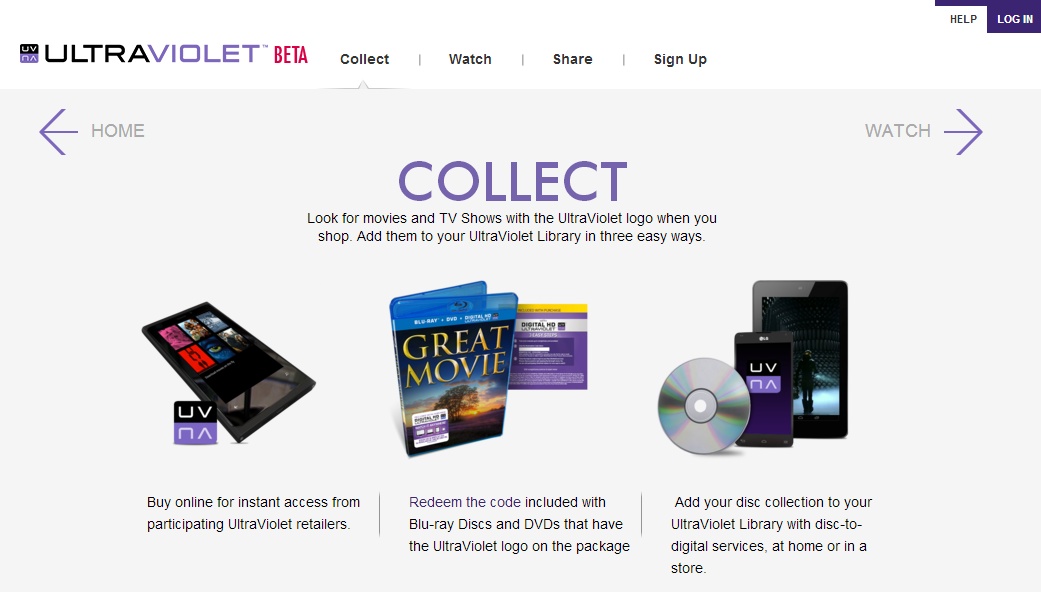

Figure 1. UltraViolet - Collect

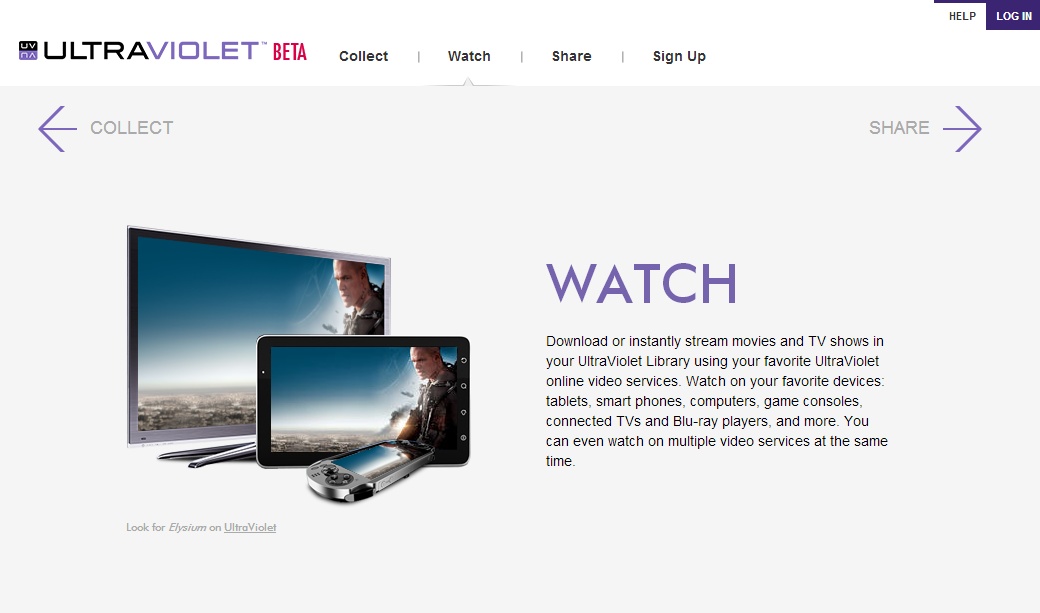

Figure 2. UltraViolet - Watch

In much the same way that DVDs recaptured the enthusiasm of

entertainment consumers in earlier years, contemporary entertainment consumer’s

(especially digital millennials) interest in the

accumulation of digital goods has given rise to an interest by industry to

capture this emerging market. These digital

enthusiasts are especially interested in the accumulation of large collections

of electronic goods, and exhibit many of the characteristics that set them

apart from consumers with less curatorial interest in their entertainment

media. They possess a depth of knowledge that is coupled with particular class

distinctions that unambiguously communicate discriminating tastes in both their digital entertainment

commodities and their archival and technical acumen. UltraViolet is a technological “solution” to some issues that many of these discerning

entertainment enthusiasts have expressed. Examples of this can easily be found

in the many discussions about the utility (and flaws) of UltraViolet’s technological implementation on discussion board, wikis and other online forums that

comprise some of this analysis. UltraViolet therefore

is a form of technological adaptation to the decline of DVD and Blu-Ray Disc

sales while trying to emulate the ascendency of Netflix, iTunes, Amazon Instant

Video and others streaming successes.

=

According to Gregory Steirer, one of the largest obstacles to widespread technological

innovation that UltraViolet attempts to accomplish is

the both the failure of many companies to abandon the 20th century

profit model (that centered on physical media) as much as it is the failure to

adapt and “adjust to their business strategies to twenty-first century

paradigms of consumption, which revolve around access, sharing/participation

and experience” (2014, p. 7) Thus UltraViolet’s

development was an appeal to the entertainment enthusiasts who still want

access to their movies and television series, albeit free from the constraints

of physical

media.

And UltraViolet explicitly targets these consumer

enthusiasts who possess both the economic and cultural capital, to capitalize

on the attractiveness of its marketing rhetoric.

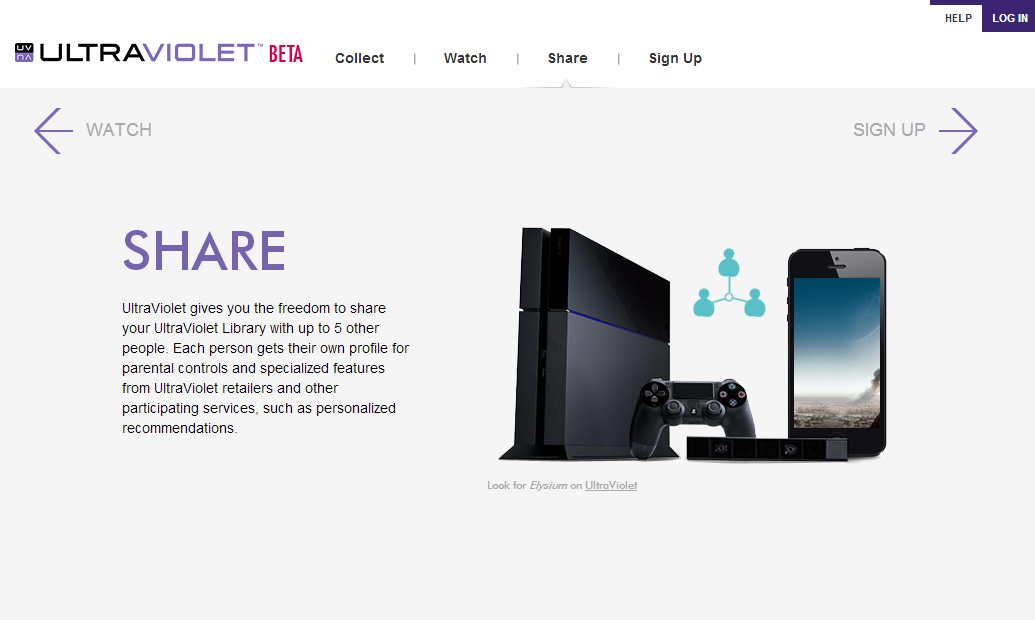

Figure 3. UltraViolet - Share

Figure 3. UltraViolet - Share

UltraViolet has a structural model to which all its consumer-participants

must adhere, and this model is both a set of regulatory rules as much as it is

an economic model of profitability for its consortium creators.

The UltraViolet Usage Model

A household account can have up to 6 members

Each member has a unique username and password

Each account holds a collection of digital rights that

represent content that it “owns”

Purchases belong to the account, regardless of which member

made the purchase

Content can be downloaded after it's purchased (with

limitations to frequency/location)

Streaming devices with the UltraViolet

logo are licensed to play UltraViolet content

Streaming services with the UltraViolet

logo are licensed to stream UltraViolet content

Each account can have up to 12 "devices" assigned

to it (can be an app or a device)

Once a device is joined to an account it can play any content

owned by that account

An account can have

up to 3 streams playing at the same time

Unfulfilled Promises, Promises, Promises

The UltraViolet system makes a

number of promises: First it says that

“By keeping a permanent record of your movie and TV show purchases, UltraViolet allows you to build a digital collection safely

and securely” though such a digital collection comes with a cost. To build

one’s digital collection, one must do one of two things: buy a legally

recognized DVD or Blu-Ray disc through an authorized retailer or buy one’s

movie or TV episode/Season digitally through a recognized online retailer. If one chooses to do the former, one may have

to go to Walmart

to

enter their purchase into the UV system to have their digital rights recorded

to their UV library (unless their purchase comes with a redemption code

included in the DVD/Blu-Ray case) – more on redemption codes later. If one doesn’t buy a digital copy and a redemption

code is missing, one must make a trip to Walmart.

Walmart also functions as an intermediary between DECE and the consumer, by

allowing consumers to provide physical copies of their DVD/Blu-Ray movies for

scanning and verification for a fee.

A Walmart technician

submits the consumers physical media for scanning and matching to a larger

database and (1) upon verification that the consumer’s media is a legitimate

(i.e. not a pirated) copy, (2) and the film matches with a title for whom DECE

has bought a license[4],

the system will then transmit the rights token to the customer’s UltraViolet account, whereupon the technician will return

the original DVD or Blu-Ray media to the customer.

Once this process is completed, this verification and rights

transmission scheme thereby enables the customer to stream their movie to a

wide variety of devices from the cloud (provided that they login with their

associated username and password combination on those devices) thereby freeing

them from the use of their original DVD or Blu-Ray media. Steirer

notes that the “purchasing and viewing of an UltraViolet

film is a complicated process that would seem to bear little in common with the

streamlined, one-stop consumer experiences provided by Apple, Netflix, and other leading

digital video services” (2014, p. 5). UltraViolet

emphasizes the “free” nature of the service, in that the Digital Library that

one creates is ostensibly “free” since it costs nothing to create and maintain

one’s library on one of the companion services (I use Vudu). Unfortunately this too is an illusion, as UltraViolet obfuscates much of the costs associated with

its use behind the veneer of user liberation.

Unfortunately when pursuing the Walmart option of scanning and verification of a consumer’s

physical media, consumer must pay a fee in order to achieve this liberation

from the physicality of DVD and Blu-Ray discs. Thus there’s a cost to According

to the most recent information from the VUDU site, the verification process

costs “$2 per DVD to convert to Standard Definition (‘SD’) on VUDU and $5 per

DVD to upgrade to High Definition('HDX) with Dolby

Digital Plus Surround Sound (when available) on VUDU. To convert a Blu-Ray disc to HDX

would cost $2. This can only be done in Walmart stores”[5].

When one considers how many DVD and/or Blu-Ray discs one has in their home, the

costs can quickly amount to a noticeable sum, especially in very large

collections maintained by enthusiasts*.

Unaccounted costs in terms of transportation, time and the inconvenience of

carrying large numbers of physical discs (especially when some movie titles are

not available because certain production studios do not currently participate) are never discussed in press accounts or

official statements.

Second, UltraViolet makes the case

that its technology is more economically friendly than other alternatives. Yet UltraViolet strategically omits some important information

about other limitations, like the fact that the digital rights cannot be transferred*,

meaning that if a consumer wanted to share their content with others, their

options are limited to only 5 people, thereby necessitating their friends to

follow through the same process of verification and payment as they themselves

did. This ultimately ensures a guaranteed revenue stream for the content

providers (Hollywood studios), retailers (online and stores where UV certified DVDs

and Blu-Ray discs are sold), Walmart

(content verifier), and ISPs (who provides the service for accessing one’s

digital library). Hollywood studios profit not simply from the associated costs

of providing rights tokens to consumers for access to their digitized content,

but they also profit by appearing to be attentive to consumers interest for the

accessibility of streaming and sharing their entertainment collections. And the

profits associated with learning about the viewing and consumption habits of

these digital consumers is invaluable to media conglomerates whose interest

about such things know no bounds. For

retailers, the added bonus of offering UV certified physical media in the form

of DVDs and Blu-Ray discs comes from the increased demand and traffic by

consumers whose interest has waned in light of emerging alternatives like Netflix, Hulu, iTunes, Red Box and Amazon Instant Video. And that bonus

comes at no cost to them since they were already selling the movies and

television series at the same wholesale cost to distributors but can now mark

up such media for the value added by virtue of the UV certified Logo.

For consumers, the

costs associated with the accessibility, sharing and streaming of one’s digital

library content is highly dependent upon a stable, high bandwidth internet

connection. The ISP expenses are also avoided in UV descriptions of its

service, although consumer’s use of its technology makes such service

indispensable to its functioning. Moreover the higher the volume of

simultaneous streams (currently capped at three), the higher consumption of

bandwidth and in some cases where a consumer’s ISP imposes caps, the higher the

costs for accessing the content that one already owns (albeit in the ostensibly

non – streamable physical form of a DVD or Blu-Ray

disc). Moreover, in those circumstances where consumers violate the caps

imposed by their ISPs, they face the equally distasteful consequences of throttling

that for most ISPs, is more about profit than network congestion(Ramirez,

2014).

And the emergence of4K

content being

included into the UV world makes this unaccounted cost even more disconcerting.

Higher bandwidth costs makes accessing the streaming digitized version of one’s

movie or TV series come at a premium that is never described in the literature

marketed to consumers. This in turn means that the ISPs will continue to

generate increased profits by virtue of their participation in the UV paradigm.

Kalker, Samtani and Wang have found another

flaw in the design of UltraViolet, which is the

belief that consumers are interested

in building digital libraries, despite the proliferation of Netflix, Hulu, iTunes, Red Box, Amazon

Instant Video and others (to say nothing of P2P systems) there are equally

valuable alternatives to the costs associated with the accumulation of digital

content advocated by the UV model (2012, p. 10). And one must

recognize that the “value of a specific distribution method or mode of

consumption is not determinable without taking into account the costs and

benefits of the alternative” (Steirer, 2014, p. 7). Some of these

criticisms are embodied in a one tongue-in-cheek fictional letter by “studio

executives to consumers” written by Lore Sjöberg illustrates the

absurdities associated with participation in the UV model:

You see, the movies

you paid for with your own money will be stored for you in your ‘locker.’ Just

like the lockers you use at school or the gym, they’ll be convenient, somewhat

secure, they won’t actually belong to you and we can do anything we want with

anything in them…Once we have your movie (which, I’m obliged to remind you, is

not actually your movie) locked up, you can access it on any of several

devices, at any time that our service is running properly, with no limitations

other than the ones in the EULA you agreed to without reading (2011).

Third,

UltraViolet strongly suggests that its model is one

that is user friendly through its simple navigation and ease of

implementation. However this assertion

belies another major criticism of its complexity. There is no explanation for

why only 12 registered devices are permitted per account, or why only 6 members

are allowed per account. And a close

examination of the terms of service, and extant literature say nothing about

what happens when libraries are merged or how to de-merge such a library. Although

UltraViolet’s literature says that consumers purchase

of digital rights (to their own content) do not expire, the few ways in which

such rights can be accessed is limited to just those few distribution services

that currently exist. Rights tokens are not currently downloadable in any format,

thus essentially making these electronic tokens insubstantial, ephemeral

promises with little consequences for their invalidation – begging the question

what exactly are consumers buying

when they pay these verification costs to one of the 10 UltraViolet

services*? Taylor observes that “Online access to movies

in your UltraViolet Library is provided by services

that participate in >UltraViolet. Most of them provide

free streams and downloads, but there is

no obligation for them to provide free access forever [emphasis added].

Thus UltraViolet’s promise of liberation also

accompanies a premium on accessibility that is defined exclusively in terms (1)

of their own choosing, (2) that have no tangible physical form and (3) possess

only the mere appearance of permanency but without any guarantee for the

future.>

Additionally, the existence of thCommon File Format which is utilized to

deliver digital content to consumers supports multiple DRM systems, and such a

scheme makes its MPEG-4 container, H.264/AVC video and multichannel audio

encrypted components part of a file format that is readable only through the use of UltraViolet compatible devices for viewing; indeed at the

time of this article there are no less than 5 different DRM technologies

implemented in the UV Common File Format *.

This is a fact that is not actively

advertised by DECE consortium partners. And while many technology companies are

increasingly implementing and adopting UV standards to make their computers,

game consoles, and Blu-ray players UV compatible, certainly not everyone will

be financially able to purchase such devices at their higher mark up. Moreover the

restrictions on the number of simultaneous streams (3) ultimately limits the

utility of any consumer’s purchase of UV compatible device over 3, though one

could own up to 12 under current limitations. Currently known compatible

devices are limited to only 9 hardware and software companies*

and there is no guarantee that current technology companies will continue to

expand the line of devices and apps which enable streaming content from the UV

system.

And an especially frustrating aspect of the UV system is the use of redemption codes

(which is the easiest method, but not especially reliable) for obtaining the

rights for streaming one’s digital content.

Movies on either DVD or Blu-Ray discs come with a redemption code often found printed

on a paper insert inside of the case.

These codes enable the user to skip the entire process of scanning the

physical disc. However the use of these codes come with their own issues:

The UltraViolet right bundled with

a disc may not match the resolution of the disc. That is, you might get an HD UltraViolet right with a Blu-ray disc or you might only get

an SD UltraViolet rights with a Blu-ray disc. You

usually get an SD UltraViolet right with DVD, but you

might get an HD UltraViolet right (Taylor, 2014)

Ultimately what this means for the consumer is that the only way to be absolutely certain

what kind of redemption code they have is to enter it into a redemption page,

check one’s library to see what resolution their content is – by which time

it’s too late to do anything about it.This is to say nothing of the fact that redemption

codes expire as well, despite the fact that one has purchased their full

price movie or TV series already, thus forgetful consumers may find themselves

being forced into a tip to Walmart to

have their media scanned (Taylor, 2014). Collectively these

objections make the ultimate winners in this contested territory of digital

ownership and distribution the major Hollywood studios and not the consumer. As

Kalker, Samtani and Wang

contend, “In the brave new world…the ultimate control over when, where, and how

these movies are being consumed lies with UltraViolet”

(2012, p. 8) and the Hollywood

Studios who produce the content for distribution through this system, and for

whom the most profits eventually

accrue.

Despite these objections, there is

no question that the implementation of UltraViolet

technology is one step in a larger scheme of maximizing profits by DECE

participants, but especially for the Hollywood studios whose fight – as content

providers – against piracy has taken its toll both in terms of profitability

and in terms of consumer loyalty. And, according Gary Arlen, studio executive’s

endorsement of this strategy has been profoundly enthusiastic. “‘UltraViolet is a new service for giving consumers a new

relationship with ownership’ says Thomas Gewecke,

president of Warner Bros. Digital Distribution.

Arlen says the studio’s research found that viewers want

“future-proof digital ownership” and “never having to worry about” access to

movies and TV shows they have bought. ‘When we examine how viewers look at

ownership, their preference is to own and control their media,’ Gewecke says. ‘UltraViolet solves

their problems’ (2013) . Here one sees

the explicit appeal by studio executives to consumer’s interest in ownership as

an opportunity to create a solution to a problem that doesn’t necessarily

exist. UltraViolet functions as a technology that

provides the appearance of control but in actually communicates an utterly false

illusion of ownership when critically examined in more detail. According to

Arlen’s interview with Mark Teitell, general manager and

executive director of (DECE), Teitell promoted four

distinct “consumer benefits” that UV technology offers:

Anytime/anywhere,

access, which Teitell says fulfills “a real

belief among consumers that if they own [content], they should be able to watch

it.

No fear of losing

things you buy,with the additional value that cloud storage eliminates

problems if discs are lost, broken or scratched. Teitell

points to UltraViolet’s “perpetual proof of purchase”

that assures access as well as “security and certainty.”

Sharing among family

and household members. Up to six people can share an account, with the ability to

set up parental control restrictions and recommendations for others within the

group to watch a title.

Interoperability, which assures that

access to the content “works the same way on different devices,” a usability

factor that did not exist in earlier electronic sell-through systems, Teitell says (2013).

These four issues are indeed legitimate concerns for

entertainment media consumers. However,

there are a number of solutions to the issues that these “benefits” touted by Teitell purport to solve. Although UltraViolet does provide

“anytime/anywhere access” if the service is working, consumers certainly do not

own the digital copy that is being actively streamed to them. Although the fear of loss, or damaged

physical media is a very real concern for consumers and enthusiasts the

“perpetual proof of purchase” that is associated with UV technology described

by Teitell is neither “perpetual” nor “certain”. As Taylor observes, “UltraViolet

retailers are required to provide streams for at least five years after you buy

the movie, but there's no guarantee you can stream forever or stream for free

after the first year”

(2014). The limitations on the number of users per

account (currently at 6) remains unexplained and while interoperability is another legitimate

concern the increasing participation in electronic standards by device

manufacturers make such concerns progressively less and less valid. For DECE

consortium members, the largest threat to UltraViolet’s

success (apart from piracy) is that UltraViolet will become a catastrophe because of younger

consumer’s disinterest in cultivating media collections as type of cultural

(and economic) practice

(Arlen, 2013). Such concerns are

certainly valid considering the popularity of “video

on demand”

services among younger demographics of consumers, to say nothing of the

popularity of P2P networks and the proliferation of high

quality files hosted on torrent sites around the world. But this belief about the lack of interest in

accumulating entertainment media content fails to account for the cultural

value that such collections generate for consumers and enthusiasts of all ages,

or the political economic costs which are imbricated through the construction

of such collections. Indeed, Bradley Schauer

pointedly predicts that “it may be the case that younger consumers, having

grown up in a digital media environment, will have the same sentimental

attachment to their digital movie and music collections despite (or perhaps

because of) their immateriality that older collectors have to their well-worn

vinyl records and DVD boxed sets” (2012, p. 45).

Consumption and Commodity Fetishism in an

All-Digital Era

Historically, the concept of “ownership” has long held an

appeal to consumers (of all demographics) as it unambiguously communicated to

the world the vested, exclusive rights one had in a commodity, as well as

functioning as a symbolic representation of one’s socioeconomic status through

disposable wealth. Indeed the widespread private ownership and accumulation of

goods “came to be seen as a socially and economically desirable from the

standpoint of capitalist production” (2006, p. 233), and according to

Ted Striphas it’s the “allure of plentitude and

respectability” that historically accompanied conspicuous consumption of

consumer goods which contributed to a “growing middle class consciousness” (2006, p. 236). I contend that the

same allure and consumptive interest persists, even for younger generations,

for their electronic media. Certainly any reader who has young teenagers will

attest to the fact that most exhibit some kind of interest in accumulation of

consumer goods. One need only read how this consumerist behavior is learned at

an early age for children who possess no disposable income of their own but

nevertheless are conceived of (and conceive of themselves) as legitimate

consumers despite this distinct disadvantage (Banet-Weiser, 2007). This consumerist

behavior was aptly described as “conspicuous consumption” by Thorstein Veblen in 1899 to describe the incessant need for

commodity ownership and display whereby “property…becomes the most easily

recognized evidence of a reputable degree of success as distinguished from

heroic or signal achievement” for middle class people and “it becomes

indispensable to accumulate, to acquire property, in order to retain one’s good

name” ([1899] 1994,

p. 19).

And I would argue that the formation of DECE (and its subsequent investment in,

and development of, UltraViolet technology) was an

explicit reaction by a number of heavily invested, capitalist parties to find

creative ways to stimulate widespread consumption of electronic consumer goods.

Those parties development of UltraViolet was a

strategy that attempted to carefully regulate the disposition of those

electronic consumer goods in an era of decreasing profit of previously reliable

lines of revenue.

Such a strategy is not without precedent and the American

historical record is replete with examples in which companies and other

corporate entities have attempted to influence and control the conspicuous

consumption of goods as a way in which benefits accrue disproportionately to

them rather than the consumer. The litigation over the photocopier

stemmed

from a perceived threat to the revenue of book publishers and authors; the

litigation over the VCR

stemmed

from a perceived threat to the revenue of Hollywood movie studies; and the more

recent litigation over P2P networks stemmed from a perceived threat to the

revenue of music studios, the consequences of which produced immediate reaction

by the entertainment industry with the promulgation of Digital Rights

Management or, DRM and the vigorous pursuit and enforcement of intellectual

property rights of copyright holders. Siva Vaidhyanathan

foresaw the consequences of such vigorous enforcement when he predicted the

rise of “a global ‘pay-per-view’ culture in which people no longer will be able

to purchase consumer goods but instead lease them from the ‘copyright-rich’

corporations” (2001, pp. 82,

181).

Conspicuous consumption of electronic consumer goods is

functionally no different from that of physical goods. Indeed, if anything the

evolution of DRM provoked a backlash against media corporations which has

created a perverse intensification amongst some consumers to accumulate

electronic goods and participate in the sociality of ownership that repudiates

the imposition of DRM technologies. And as Stini, Muve and Fitzek point out, “Most

providers of digital content are currently fighting a losing battle against

piracy copies [sic] distributed via peer-to-peer file sharing in the internet

or on self-burned DVDs and CDs” (2006, p. 1). Moreover they

contend that the imposition of DRM on consumers is a failing strategy since

“DRM artificially reduces the usefulness of the digital content by limiting the

actions that a legitimate user can perform on the content. Thus a consumer who legally purchases digital

content protected by DRM not only has to pay for the content but also gets an

inferior product compared to someone who obtained an illegal, unprotected copy

for free. An approach that relies on ineffective technology while putting

legitimate owners at a disadvantage isn’t going to succeed” (2006, p. 1).

Certainly history has shown that their conclusions have

proven true given the widespread use of P2P networks today as a primary source

of digital content exchange. However, in

those cases where DRM is hidden from view or is less visible to consumers (as

is the case for UltraViolet), corporations and

conglomerates like DECE can studiously avoid that consumer backlash while

conveniently harnessing that reinvigorated interest in conspicuous consumption

by digital enthusiasts. And the membership of the DECE consortium have a potent

financial incentive in maintaining that interest, when companies like Hollywood

studios “that control the copyrights of cultural ‘software’ – back catalogs of

music, film, television shows, etc…are considered by many investment firms to

be extremely lucrative, perhaps the most profitable companies in the

communications market” (McLeod, 2001, p. 6).

Not altogether different from the consumerist behavior of

conspicuous consumption is that of commodity fetishism. According to Andrew

Edgar and Peter Sedgwick, commodity fetishism is best defined as a circumstance

in which “properties such as price, which are ascribed to objects through

cultural processes, come to appear as if they were natural or inherent

properties of the objects…The theory of commodity fetishism therefore suggests

that capitalism reproduces itself by concealing its essence beneath a deceptive

appearance. Just as quality appears as quantity, so objects appear as subjects

and subjects as objects. Things are

personified and persons objectified” (2002, pp.

71-72).

Under this definition then, UltraViolet anticipates

that the digital consumer’s interest in the consumptive practice of

accumulating film and television content in their digital library represents

the successful fulfillment of its technoeconomic

potential. Indeed the value that digital

consumers place upon the rights to streaming content that they already own is a

fundamental premise upon which UltraViolet is

constructed. It’s the belief that UltraViolet’s

technology offers added value to commodities that digital consumers already

possess, thus making the expenditure of additional money eminently reasonable

under the rhetorical marketing rhetoric created by DECE participants. Moreover, the need to pursue the purchase of

these digital rights is part of a larger strategy that not only anticipates the

commodity fetishism of consumers but also encourages it, while simultaneously

concealing the logical flaws inherent in the economics of such consumption as

described earlier. Thus, these consumers

are commodified as vital components of a new revenue stream while their digital

rights are personified as the way to display one’s cultural savvy,

technological acumen and demonstrate to the world the extent of an enthusiast’s

commitment to the Avant-garde abandonment of physical media and the adoption of

all things streaming, downloadable and digital.

Equally important to this observation about the impulse to collect,

is the sociocultural value of these digital commodities which influence their

conspicuous accumulation since “…the kinds of television shared in P2P networks

tends to be the most highly valued and aestheticized, scripted prime-time

comedies and dramas addressed to younger, more affluent and masculine

audiences” (Newman, 2012, p. 466). The fact that

quality is a primary determining factor which defines the sociocultural value

ascribed to such digital collections is, I argue, especially important to the

DECE consortium for whom UltraViolet was created. UltraViolet originated as a means to increase profits

amidst an era of increased P2P exchange and to combat piracy while advancing a

new revenue stream during a period of precipitous decline in physical media

sales. Indeed, the strategy behind the implementation of UV technology, is to guarantee

(1) the purchase of “legally sanctioned” physical media as much as it is to

pursue new revenue for digital movies and television while (2) compelling

consumers to validate their purchases of that “legally sanctioned” content.

Unfortunately, this

strategy fails for a number of reasons, the least of which is the increasingly

evolving cultural pessimism against the digital ownership of “legally

sanctioned” content that strongly resonates with both older and younger

consumers alike (Striphas, 2006; Stini, Mauve, & Fitzek, 2006;

Dixon, 2013)

and that threaten to destabilize the model upon which UV technology relies. To

understand what this threat is and the implications for UltraViolet

and other emerging technologies like it, one must understand the sociocultural

conditions that influence the ways in which society conceives of digital

ownership as an economic practice of conspicuous consumption.

Derek Kompare notably observes that

at one point in time, the accumulation of entertainment content on physical

media was construed as an important new type of commodity relationship whereby

DVD box sets become collectible objects.

In his assessment, consumers “rent or purchase discs for home use with

the revenue split among retailers, wholesalers, distributors and producers” and

this scheme soon proved to outpace traditional revenue sources just two years

later when in 2002, “video revenue totaled $20.3 billion, more than twice the

take at the box office. Accordingly home

video, rather than theatrical exhibition, is the primary source of profits in

Hollywood” (2006, p. 339). Especially

important to this analysis of, is what Kompare

defines as the relationship of consumer to commodity, noting that it’s the

“existent, tactile relationships between readers and books and listeners and

sound recordings” that deeply resonated with people thereby

making DVD’s so popular, especially as single DVD discs took up the same

physical space. Indeed, the similarities

between book collections and DVD collections functioned because “discs are thus

spatially congruent with existing fixed media forms, fitting easily into

domestic settings on shelves entertainment centers and coffee tables” (2006, p. 339).

It’s precisely this type of familiarity that is so crucial to

the digital distribution systems of today.

While the tactile interaction is missing, the sociocultural value

associated with the prestige of collecting remains very popular among digital

content enthusiasts. One finds this

regularly on display on social networking sites, on discussion board forums*

and elsewhere when consumers can list the various minutiae of their digital

collections*.

Indeed, I myself am a culprit, deriving satisfaction from the social value

ascribed to my digital collection with notations about the size, number and

resolution quality of my content (with much chagrin, I’ve even done it here –

see footnote 5). Thus the ways in which value is ascribed to our digital media

collections can best be understood as a psychological manifestation of

technological developments within existing social, commercial and cultural

formations. In much the same way that Kompare argues

that “extensive media collections, so much a part of the modern domestic

environment, require effective, aesthetically compatible storage. Whether the

collections consists of books, LPs, CDs, VHS tapes, laserdiscs, or DVDs, users

generally take care to store their media properly, ideally in some form of

order” (2006, p. 347) so too must

consumers be able to experience the process of ordering their digital content in ways that reproduce

the feelings, associations that would normally accompany physical media collections and it is clear that UltraViolet

is an attempt to accomplish this objective.

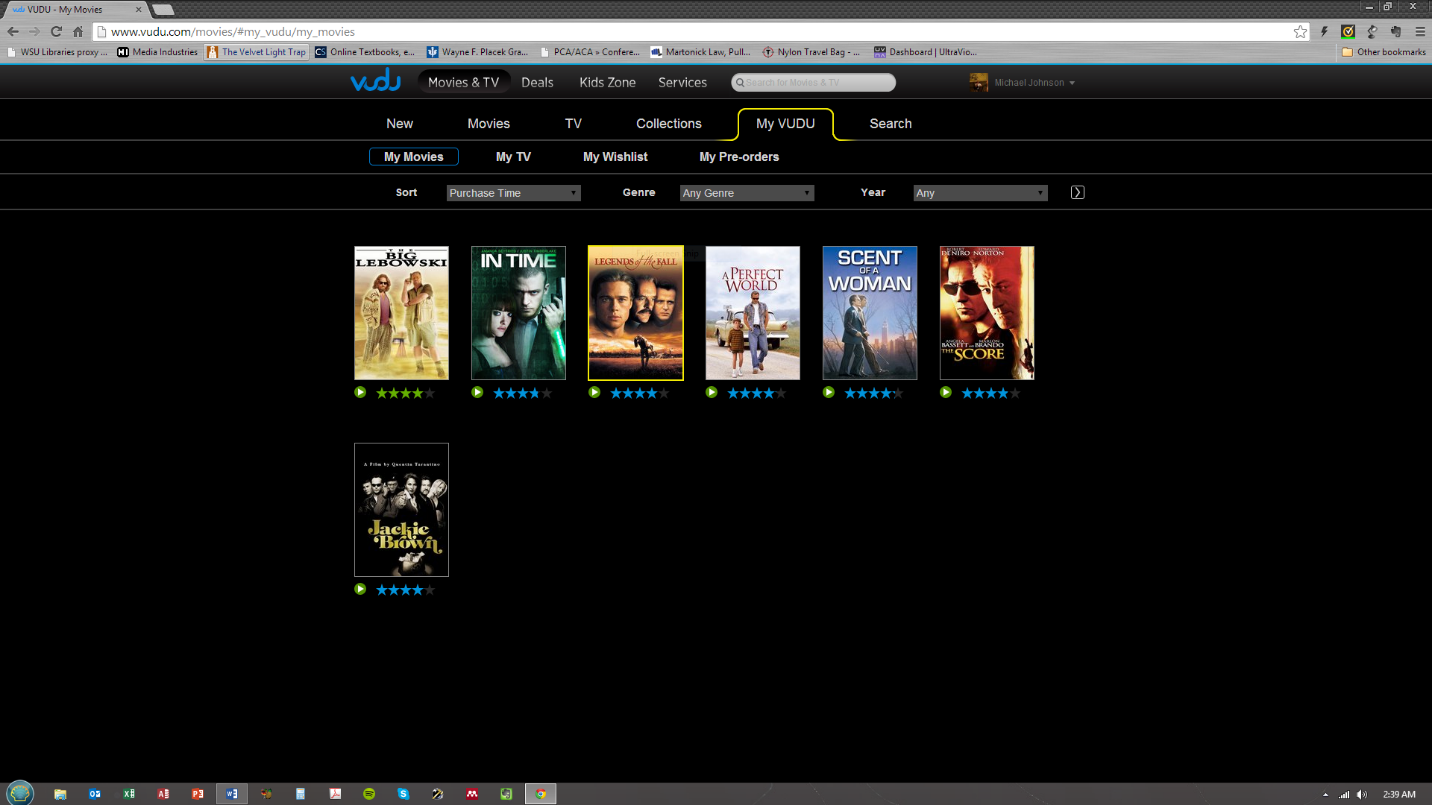

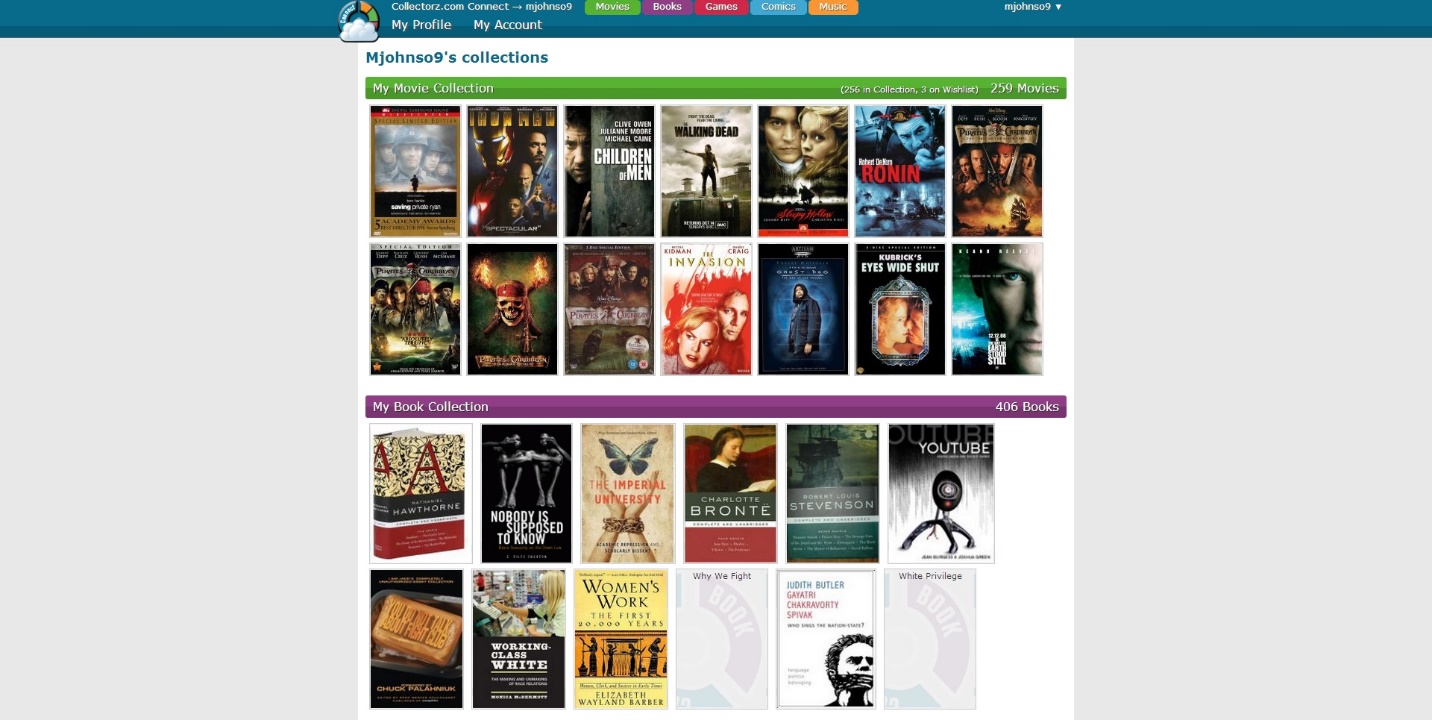

The visual interface that lists one’s collection functions

much like a bookshelf does in one’s home, by symbolically but unambiguously

communicating a message about the preferences and tastes one has in their

entertainment choices (See Figure 4). UltraViolet’s

web portal is complicit in the process of exemplifying one’s digital

entertainment collection a reflection of the enthusiast’s “manifested

preferences” and whose social position as a connoisseur demonstrates their

cultural competency. In keeping with Pierre Bourdieu’s theory of taste, UltraViolet’s primary mechanism of interaction between

consumer and commodity, solidifies the enthusiast’s personal investment in the

curation of their digital collection, thus reifying the accumulation imperative

amongst these consumers. Indeed this electronic representation of one’s digital

library replicates a marketing rhetoric “that appeals to the collector’s desire

to recognized as a privileged insider” who have knowingly relinquished their

“material ownership for the sake of accessibility and convenience” (Schauer, 2012, p. 36). UltraViolet

manipulatively exploits the “feelings of aesthetic pleasure, achievement,

purposefulness, mastery and status” (Belk, 2001, p. 140) that enthusiasts derive from such

accumulation as well as the cultural capital that such individuals possess,

thereby deviously enhancing collector’s strong sense of investment and

ownership.

Claims of collection size, lossless audio and video quality,

and diversity of content proliferate amongst enthusiast reaching 217 pages in

length on UltraViolet forum pages and populated with

photos of one’s digital collection. Such displays and the discourses of

ownership and cultural taste embodied in one’s digital collection illustrate a

conscious endorsement of commodity fetishism for digital entertainment media*. Indeed,

Schauer contends that “the aesthetically pleasing and

prominent display of a collection reinforces the collector’s sense of order,

control and status” (2012, p. 44) [emphasis added]. Indeed

frequent comparisons are drawn between enthusiasts for whose collection comes

closest to that of the total titles supported in the UltraViolet

collection, currently numbering approximately 6500 titles as of the date of

this research*.

In much the same way

that P2P systems circulate digital content between and amongst itself, so too

does digital content live on in under the auspices of UltraViolet’s

many different organizational hierarchies. I argue that the collection and

organization of one’s digital content (under the aegis of UltraViolet’s

library) functions much like a practice where one’s cultural value can be

assessed by others, thus making UltraViolet’s

indispensability to avant-garde consumers renewed. Indeed Newman’s research

confirms this conclusion when he notes that “the superiority of new

technologies is given as self-evident and as distinguishing a youthful,

masculine and technologically adept community from the mainstream” of consumer

society. The collection, accumulation, organization and distribution of digital

content via UltraViolet’s system functions as a kind

of imperative for the improvement of cultural consumption by appearing to

empower individuals to take control over their content.

Indeed, there

is an entire suite of desktop, cloud and mobile app software that exists simply

for the purpose of tracking, managing, updating and sharing one’s media

collections to include movies, books, music, comics and games (Hoogerdijk

& Harte, 2014).

Although digital content, by its very nature is intangible, the experiences

that accompany its accumulation is directly similar to that experienced by

collectors of physical media whereby consumers derive both sociocultural

prestige and personal satisfaction from its collection, and organization. Below

one will find a screenshot of my own collection utilizing one software’s

web-enabled portal that I’ve made publically accessible for review.

SEQ Figure 4. -

My Vudu Library (7/18/2014).

Figure 5. My Collectorz Book & Movie

Collections (7/18/2014).

Michael Newman contends that the exchange of telenarrative content on P2P networks represents a similar interest in the

ordering of digital content which “bespeaks the high value of some forms of TV

to media consumers eager to locate and select episodes and to devote time and

resources to their acquisition and experience” (2012, p. 465). Much like the P2P

digital content that is the target of Newman’s study, the availability and

desirability of legal online downloads or streaming options like UltraViolet possess serious limitations since “the terms

are never entirely the audiences own preferred options. Downloads carry DRM to

make the film’s playable only with certain software or devices, which impedes

their usability and long-term value” (2012, p. 477). These restrictions,

have spawned a plethora of objections by media enthusiasts, consumer groups and

legal rights entities (Electronic Frontier Foundation, 2014; Schneier,

2014).

Collectively these entities in pursuit of the digital rights movement, conceive

of technology not simply as a commodity but also as a resource that “speaks a

certain kind of language about cultural production – a participatory ethos and

its policies. Technology can also be thought of as…an opportunity to allow for

a particular relationship between consumers and content” (Postigo,

2012, p. 177).

And technologies like UltraViolet

do indeed offer an opportunity to challenge the ways in which consumer

enthusiasts have traditionally conceived of themselves and the ways in which

their consumptive practices look like. When UltraViolet

is successfully implemented according to the sociocultural objectives and

economic goals of its consortia members, it explicitly attempts to convince users that the world ought

to be a certain way” and that “way” is one where consumer activity is in

service to content providers and unfavorable to consumers. Moreover, UltraViolet simultaneously becomes a “space of contest

where the players in this particular struggle come to realize their worldviews

and convince (or cajole) others into embracing those views” (Postigo, 2012, p. 177) of unrestrained,

conspicuous consumption. There is no question that UltraViolet

has indeed become a technology that encourages a “form of consumption [that]…increasingly

controls our level of access and involvement” (Postigo,

2012, p. 178)

between commodity and consumer, content producer and commodity collector. Hector Postigo

points out that “…it is only when we willingly adopt technological systems that

they become embedded in the social architecture and obtain their formidable

power to influence society in certain ideological ways” (2012, p. 178). And if his

assertion is correct, then it lies with consumers to exercise a healthy dose of

skepticism about solutions to issues that technologies like UltraViolet

purpose to solve.

Media of the Future, Accessibility and Socioeconomic Divide

There is little question that the future of entertainment

multimedia content lies with digital distribution and streaming. When “33 million subscribers stream more than

a billion hours of Netflix content

every month, using one third of peak US bandwidth to do so” (Paskin, 2013, p. 101)how can we ignore

what this evidence states or its implication for the future? The future of

digital streaming media is increasingly challenging traditional television as

well. Although the development of original programing by Netflix (e.g. “House of Cards”, “Orange is the New Black”, etc.)

and the accompanying financial investment such development represents, the

complexities of human consumption makes even these propositions an unstable

one. The paradoxical nature of our human

nature means that highly watched telenarratives like NCIS

or the The Big Bang Theory, does not mean that

they are equally highly valued

series, as is the case with Breaking Bad

or Game of Thrones (Stinson, 2013). Indeed research

has concluded that some series occupy a position as a “loss leader” where their

anemic, substandard financial profitability is typically outweighed by their

sociocultural value, much like that of HBO series like The Wire and True Blood (Johnson Jr., 2013).

Indeed, this phenomenon has provoked a near crisis within

traditional media assessment and measuring since the traditional model of Nielsen

rating

is about to collapse when “a full 40% of Twitter’s traffic during peak usage is

about television” and that in the future “a show’s tweetability

may be just as crucial as the sheer size of its audiences” (Vanderbilt,

2013, p. 94).

This “loss-leader” phenomenon also explains why Breaking Bad has a bigger audience on Netflix than it does on its own home studio/channel, AMC and according to one

executive the process of binge consumption of entertainment content suggests

that “people who did this (binge watch an entire season) were much more

attached to the shows. And because they were more attached to the shows, they

reported more value in watching them on Netflix” (Paskin, 2013, p. 103). Carter and Stelter have found that “binge viewers” are “…more

attentive. They are less distracted. They have picked a time when they have the

opportunity for more engagement than they would have if their kids were bugging

them or they had three things to do at once” (2012).

In a

future world where digital distribution of entertainment content has become the

norm and physical media has been effectively replaced and relegated to museums,

who wants to access digital content and who can afford to do so becomes the

primary criteria upon which conspicuous consumption practices will revolve. UltraViolet functions in eerily similar ways to what Jeremy

Rifkin argues is the "outsourcing of ownership" and where "the

purchase of lived experiences becomes the consummate commodity” (2001).

Indeed, UltraViolet’s practice of contracting third

parties to provide and maintain access to digital content thus freeing

Hollywood studios from the financial burdens of maintaining storage space for

actual digital copies of films for download serves only to give consumers a

commodified entertainment experience, rather than a tangible product.

Author Bio

Michael Johnson Jr., Ph.D., is a full-time instructor in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender, and Race Studies (CCGRS) at Washington State University, where he currently teaches both introductory and upper-division, interdisciplinary undergraduate courses in the Department of Critical Culture, Gender, and Race Studies. He earned his B.A. at the University of New Orleans (2005), an M.L.A. in social and political thought at the University of South Florida (2008), an M.S. in library and information science from Florida State University (2015), and his Ph.D. in American studies at Washington State University (2013). His book, Tickle My Fancy, Fat Man: Emerging Images of Race and Queer Desire on HBO, is currently under contract with Lexington Press, in its Critical Studies in Television Series in press fall 2015. His work can be found in the Journal of Men's Studies, Reconstruction: Studies in Contemporary Culture,Journal of Prisoners on Prisons, The Velvet Light Trap, Journal of Popular Television, and Educational Studies, and he has published chapters in edited collections by ABC-Clio, Praeger, Lexington Books, Palgrave Macmillan, Information Age Press, University of New Mexico, and Cambridge Scholars Press, to name a few.

Mjohnso9@wsu.edu

References

Arlen,

G. (2013, March 22). UltraViolet: This Time it’s About Distribution, Not

Just Display. Retrieved July 15, 2014, from

http://www.ce.org/i3/Features/2013/March-April/Ultraviolet-This-Time-it%E2%80%99s-About-Distribution,-Not.aspx

Banet-Weiser, S.

(2007). Kids Rule!: Nickelodeon and Consumer Citizenship. Duke

University Press.

Belk, R. W. (2001). Collecting

in a Consumer Society. London: Routledge.

Carter, B., &

Stelter, B. (2012, March 4). DVRs and Streaming Prompt a Shift in the

Top-Rated TV Shows. The New York Times.

Dixon, W. W. (2013).

Streaming: Movies, Media and Instant Access. Lexington: University

Press of Kentucky.

Edgar, A., &

Sedgwick, P. (2002). Cultural Theory: The Key Concepts. New York:

Routledge.

Electronic Frontier

Foundation. (2014, June 26). DRM. Retrieved July 20, 2014, from

https://www.eff.org/issues/drm

Gray, J. (2010).

Entertainment and Media/Cultural/Communication/etc. Studies. Continnum:

Journal of Media & Cultural Studies, Vol.24, No.6, 811-817.

Hoogerdijk, A.,

& Harte, M.-J. (2014). Bitz & Pixelz. Retrieved July 15, 2014,

from http://www.bitzandpixelz.com/

Johnson Jr., M.

(2013). “Discourses of Distinction” as Conspicuous Consumption: An

Interdisciplinary Analysis Of Race and Queer Desire on HBO’s The Wire and True

Blood. Pullman: Washington State University.

Kalker, T., Samtani,

R., & Wang, X. (2012). UltraViolet: Redefining the Movie Industry? MultiMedia,

IEEE Vol.19, No.1, 7-11.

Kendrick, J. (2005).

Aspect Ratios and the Joe Six-Packs: Home Theatre Enthusiasts' Battle to

Legitimize the DVD Experience. The Velvet Light Trap, No. 56, 58-70.

Kompare, D. (2006).

Publishing Flow DVD Box Sets and the Reconception of Television. Television

& New Media, Vol.7, No.4, 335-360.

Matthews, D., &

Schrum, L. (2003). High-Speed Internet Use and Academic Gratifications in the

College Residence. The Internet and Higher Education, Vol.6, No.2,

125-144.

McLeod, K. (2001). Owning

Culture: Authorship, Ownership, and Intellectual Property Law. New York:

Peter Lang.

Newman, M. Z.

(2012). Free TV File Sharing and the Value of Television. Television &

New Media, Vol.13, No.6, 463-479.

Paskin, W. (2013,

April). There's Money In The Banana Stand! Wired Magazine, pp. 100-103.

Perren, A. (2013).

Rethinking Distribution for the Future of Media Studies. Cinema Journal,

Vol.52, No.3, 165-171.

Postigo, H. (2012). The

Digital Rights Movement: The Role of Technology in Subverting Digital

Copyright. Cambridge: MIT Press.

Ramirez, L. (2014,

February 20). How Data Caps May Limit Your House of Cards Viewing Marathon.

Retrieved July 15, 2014, from

http://dealnews.com/features/How-Data-Caps-May-Limit-Your-House-of-Cards-Viewing-Marathon/986406.html

Reed, T. (2011).

Popular Culture. Year's Work in Critical and Cultural Theory, Vol.19, No.1,

141-158.

Rifkin, J. (2001). The

Age of Access: The New Culture of Hypercapitalism, Where All of Life is a

Paid-For Experience. New York: Putnam.

Saukko, P. (2003). Doing

Research and Cultural Studies: An Introduction to Classical and New Methodological

Approaches. Thousand Oaks: Sage.

Schauer, B. (2012).

The Warner Archieve and DVD Collecting in the New Home Video Market. The

Velvet Light Trap, No.70, 35-48.

Schneier, B. (2014).

Defective By Design. Retrieved July 20, 2014, from https://defectivebydesign.org/guide

Sjöberg, L. (2011,

December 11). Alt Text: UltraViolet Makes Honesty Almost Convenient. Wired

Magazine.

Steirer, G. (2014).

Clouded Visions: UltraViolet and the Future of Digital Distribution. Television

& New Media, Vol.1, No.16, 1-12.

Stini, M., Mauve,

M., & Fitzek, F. H. (2006). Digital Ownership: From Content Consumers to

Owners and Traders. MultiMedia, IEEE Vol. 13, No.4, 1-6.

Stinson, L. (2013,

April). Passion Trumps Popularity. Wired Magazine, p. 101.

Striphas, T. (2006).

Disowning Commodities: EBooks, Capitalism and Intellectual Property Law. Television

& New Media, Vol.7, No.3, 231-260.

Taylor, J. (2014,

May 8). UVdemystified.com. Retrieved July 14, 2014, from FAQ:

http://uvdemystified.com/uvfaq.html

Vaidhyanathan, S.

(2001). Copyrights and Copywrongs: The Rise of INtellectual Property and

How It Threatens Creativity. New York: New York University Press.

Vanderbilt, T.

(2013, April). The New Rules of the Hyper-Social-Data-Drivin, Actor-Friendly,

Super-Seductive Platinum Age of Television. Wired Magazine, pp. 90-94.

Veblen, T. ([1899]

1994). The Theory of the Leisure Class. New York: Dover.<

Notes

[1] Referred interchangeably

herein as “enthusiasts” and “consumer enthusiasts”

[2] A consortium of film

studios, tech companies, retailers, device manufacturers, ISPs and other

companies

[3] Courtesy of (Taylor, 2014)

[4] The studios supporting UltraViolet include Paramount Home Media Distribution, Sony

Pictures Home Entertainment, Twentieth Century Fox Home Entertainment,

Universal Studios Home Entertainment and Warner Bros. Home Entertainment.

[6] And in my own case, would

total well over $600.00 for my growing collection of over 300 movies.

[7] Though, as of the date of

this article, a consumer’s movies can be temporarily

streamed up to 5 other people; this

accessibility is however, restricted since each slot must be deactivated before

being made available for another person’s access

[9] Google Widevine;

Marlin DRM; OMA CMLA-OMA v2; Microsoft PlayReady; Adobe Primetime DRM; DivX

Plus

[10] to Windows (including Windows

Phone 8 and Microsoft Surface RT), Mac, iOS (iPhone and iPad,

including AppleTV using AirPlay

mirroring), Android (including Kindle Fire and Nook tablets), PlayStation 3, Xbox

360, Roku, Chromecast, and Google TV

|

|