|

The use of widescreen aesthetics — both, actual wide-film film formats such as CinemaScope or faux widescreen processes such as letterboxing — exists for visual appeal and product differentiation. Historically, widescreen processes were initially deployed by the fledgling film industry as part of the battery economic life preservers in the fight against television in the early 1950s. However, wide-film processes had been experimented with in film as early as the 1890s as industrial groups were still striving for standardization of film stocks and negative widths. (Belton, 1992, 3) Widescreen processes have always had the goal of product differentiation as the ultimate draw, but after they became integrated into standardized film production practices in the 1950s, the aesthetic qualities and the subsequent critique of such choices has been little discussed. If the aesthetics of widescreen film processes have lacked rigorous scholarship, then even less has been written about digital technologies that utilize widescreen processes for cultural clout. The advertising industry has capitalized on the use of widescreen as a visual technique in both television and online ads. In short, why do media content producers, specifically advertisers, use letterbox techniques for mediums such as television and online content when they will most likely be viewed in a 4:3 aspect ratio monitor? Media producers of such ads confess that the goal is to make “their work more ‘cinematic’ . . . with the look and feel of a feature film.” (Vagoni, 11/08/99, 49) Therefore, some digital content producers, much like the film industry, utilize the wide frame of feature filmmaking for product differentiation via the aesthetics of the form itself. This essay will examine the use of widescreen aesthetics, particularly letterboxing, as a production device in the online advertising campaigns of BMW Films (Star) and Buick (Tiger Trap). Both ads feature the widescreen aesthetic via letterboxing, and Buick’s Tiger Trap even uses a split-screen technique that has enjoyed sporadic use since the 1960s and 1970s and is virtually new in online advertising. Both campaigns were launched on the Internet and both are long-form (6-8 minutes) cinematic ads, therefore they are useful texts to examine. Unlike their 30-second and minute-long counterparts, they have the added benefit of having already captured their audience, and therefore the letterboxing device cannot be reduced to merely an attention grabber. To fully examine what widescreen means and how it became endowed with those meanings, it is useful to examine the film studies’ literature with regard to scholarship on widescreen, as well as criticism of the widescreen aesthetic in online content concerning both advertising and even video games. Therefore, this paper will serve as a step in the process of filling the literature gap regarding widescreen aesthetics across a variety of media and chiefly that of online technologies. A final note about the variety of media under consideration in this essay: I differentiate my discussion and subsequent discussion between the aspect ratio of content traditionally viewed in a theater (usually between 1.85:1 and 2.35:1) and that viewed on a television or most computer monitors (4:3). Therefore, while the shape of both television and computer monitors are shifting to a more theatrical 16:9 aspect ratio, this essay is concerned with historical constructions of media content consumed in the 4:3 standard. Widescreen Film Criticism Certain scholars have tackled particular areas of widescreen criticism and analysis in film studies. In Widescreen Cinema, John Belton (1992) offers both a cultural and ideological critique of the industrial and social factors present for widescreen’s adoption. David Bordwell (1985) has surveyed earlier scholars’ critiques of the aesthetic and mise-en-scene signifiers of widescreen cinema, and presents a slightly-less-than-overwhelmed assessment regarding widescreen’s impact upon filmmaking practices and reception. Finally, there is Charles Barr’s (1963) “CinemaScope: Before and After,” (an essay Bordwell (1985) calls both “extraordinary” and “a landmark” (20-21)) which argues that widescreen cinema challenges spectators to be “alert,” but should strive for a “gradation of emphasis” regarding its implementation. (11) Barr’s contention is that widescreen cinema (specifically CinemaScope) offers the possibility of “greater physical involvement” for the spectator and a “more vivid sense of space.” (4) Essentially, Barr’s essay reifies the notions that Andre Bazin had put forth regarding the “myth of total cinema” — that is, widescreen cinema allows for fewer edits, and thus longer takes, which Barr and Bazin claim allows for the spectator’s deeper perceptual submersion within the visual narrative. Critical reactions to widescreen aspect ratios and their importance to the canon of film studies are, at best, conflicted. Both Belton and Bazin assert that widescreen aspect ratios offer the possibility of greater realism and cinematic verisimilitude. Even Francois Truffaut (1953) falls under the spell of realistic potentialities that widescreen might possess. Bordwell ultimately advocates a formalist approach of evaluating stylistic and technological devices within a historical framework. For Bordwell, while there may be aesthetic changes intrinsic to widescreen’s assimilation, they are simply markers along the road to industrial assimilation of a new technology. Barr’s essay is where I will locate most of my energy, because it is the canonical text from which others spring. Barr’s contention is that widescreen formats and their attendant “special potentialities” achieve an aesthetic unattainable by Academy ratio (4:3) films. (9) Barr asserts that “the more open the frame, the greater the impression of depth: the image is more vivid, and involves us more directly.” (10) Barr goes on to explain that “it is [this] peripheral vision which orients us and makes the experience so vivid . . . this power was there even in the 1:1.33 image, but for the most part remained latent.” (11) His general claim is that widescreen achieves greater realism through the use of the long shot and long take, and the minimal use of montage and/or editing. Like Bazin before him, Barr praises the idea of greater open space within the wider frame, and as such, claims that the need for insert shots that command the spectator to “look here and look at this” — Bazin hoped that widescreen would bring about “fin du montage” — is somehow lessened. Barr sees the format as lending itself to “greater physical involvement” and thus portraying imagery as “completely natural and unforced.” (11) He contends that such involvement and natural aesthetics are due to widescreen’s use of long shots and airy visuals that did not exist in the Academy ratio. Ultimately, Barr reasons that, “we have to make a positive act of interpreting, of ‘reading’ the shot.” (18) In this act of interpretation, Barr isolates one of the primary claims of widescreen critics: due to the larger screen area of a theatrically projected CinemaScope film and the longer takes/fewer edits of the initial widescreen films, audiences were encouraged to perform new viewing practices. The critical reactions to widescreen and its attendant aesthetics in film are a good place to begin a discussion of what exactly widescreen means in digital and online formats. If Barr’s assertion that the widening of the frame in fact results in “greater physical involvement” and encourages viewers to “interpret” and/or “read the shot” then widescreen’s deployment by the advertising industry makes perfect sense. However, Barr also contends that the hallmark of widescreen images is a more open frame with a “greater . . . impression of depth” and an image that is “more vivid, and involves us more directly.” Barr claims that this power was not present in the Academy ratio or “remained latent.” With regard to television, this problematizes the use of such a technique by advertisers because if the 4:3 image does not allow for “greater physical involvement,” then not using it is to the industry’s detriment. This is of course a moot point because letterboxing on television was not popularized until Woody Allen secured a contractual agreement with United Artists in 1985 which gave him control over the video versions of his work, and Allen’s Manhattan (1979) was the first home video released in the letterbox format. (Belton, 1992) Allen’s historical and cultural associations with the wider frame will be of importance as we continue to examine the cultural capital with which letterboxed media is endowed. Television, the 4:3 frame, and Letterboxing Advertising Age critic, Bob Garfield (1992), critiquing a Mercedes-Benz television spot remarks that “foreign-film and Woody Allen buffs will recognize . . . the letterbox technique” utilized in the production. Garfield further notes that Mercedes’ reason for “fiddling with the frame” is “Maximum Instantaneous Visual Impact (MIVI). (77) This notion of MIVI is certainly not a new concept in advertising, but it is a useful framework by which to examine the use of letterboxing where none is warranted. In other words, Allen and foreign filmmakers became associated with letterboxing because of a desire to control the visual integrity of their creations. Thus, the cultural capital associated with Allen and foreign films is also associated with their visual style, and furthermore, their desire to maintain that style regardless of media format (i.e, film-to-video transfer). This demands a bit more explanation. CinemaScope and its counterparts were rolled out at a time when the motion picture industry was waging a profit (and popularity) war against television. One of the primary draws of the wider frame (not to mention color and stereo sound) was that it would not fit on the small, black-and-white consumer television set. Therefore, to see a CinemaScope film, consumers had to leave their homes in the suburbs and venture back into the motion picture palaces. When films made after 1952 were licensed for broadcast on television, they were panned and scanned, which Belton (1994) has argued essentially amounts to a “recomposition” of the frame’s content. (270) In this process, the wider negatives are panned and/or scanned horizontally or re-edited with essential pieces of content lost completely. Ironically, the widescreen formats, which were introduced to combat television, were aesthetically dismembered in order to fit on television screens. One of the initial ways of dealing with the horrors of panning and scanning was to release films in a letterbox format – the matting of the image with black bars at the top and bottom of the image to preserve the film’s original composition but shrinking the entire image to fit the reduced screen area. The letterboxing technique therefore achieves both MIVI — another phrase for product differentiation — and cultural significance simultaneously. Advertisers lease visual space and/or airtime; ironically, by letterboxing their texts, advertisers are giving away valuable visual real estate. In short, Allen and foreign films sacrificed total image surface on the television screen to preserve their films’ artistic integrity and composition. Advertisers and other media producers use letterboxing techniques for differentiation of product. In Garfield’s words, “commercials have no such imperative” to use letterboxing, but rather it is an authorial choice with the end goal being MIVI. Therefore, letterboxed content began with film-to-video transfers that were proprietary to television. The letterbox process, which involves the masking of a portion of the image to achieve the film content’s original aspect ratio, is one that provides a useful function to filmmakers and their audiences by preserving the text’s original format. However, when this process of letterboxing is appropriated to non-proprietary formats such as online media, we must assume that the process of letterboxing itself has meaning. Thus we are led to consider what does letterboxed content mean? A first consideration must deal with mise-en-scene and how it is changed in a letterboxed frame. By constructing a widescreen space in a native Academy ratio space, letterboxing manipulates spatial relationships and their subsequent reception. As Garfield states, to letterbox content when there is no imperative to do so is striving for MIVI. However, once the “initial” attention is achieved, viewers are left with content that has colonized a certain aspect ratio without their consent. This concept demands a bit of unpacking. Consider your computer monitor or television screen. More than likely it presents a 4:3 aspect ratio. Therefore, like letterboxed films on VHS or DVD, monitor space that is available is masked without input from the consumer. Thus, the content authors have made a decision to colonize available monitor space. In other words, a consumer has a choice (often unbeknownst to them, unfortunately) between a widescreen or full screen format for a film or video. This is especially true with the proliferation of DVD formats, which often offer both formats on a single disc. Therefore, consumers may choose how much monitor (TV or computer) space they are willing to “sacrifice” in viewing the text. With letterboxed ads however, this is not the case; the decision to colonize monitor space has been made by the media producers and consumers must view the matted content. Also, online advertising such as that of BMW Films and Buick are dealing with audiences that have come to their ads, rather than having been snared by MIVI or some other attention grabber. Media producers state that “letterboxing simply works better from the standpoint of cropping the images in the frame and creating a sense of . . . ‘visual tension.’” (Vagoni, 1999, 48-50) Further, advertisers say that the use of the letterboxing device allows “[a] spot to exhibit compositional possibilities that the regular TV [format] would not have provided.” (Vagoni, 1999, 48-50) This “visual tension” and the resulting “compositional possibilities” are what I have termed “colonization” with regard to the visual image. In sum, content producers take a nod from the cultural cache associated with letterboxed films, usually foreign or art-cinema films, and utilize this aesthetic tradition by appropriating a consumer’s screen space. Once we are past the fact that ad producers are colonizing space, then we are back to the question of meaning. If we are to accept that letterboxing, because of its lineage from Allen, foreign films and cinema in general, denotes “highbrow notions of artistic merit and dramatic impact” we need to examine how these concepts are delivered. (Vagoni, 11/08/99, 48-50) The notion of “visual tension” is a significant one because both the BMW Films’ spots and Buick’s ad rely upon the tension of the formatted space to deliver their content. By assuming this cinematic visual style, the ads have already achieved the goal of equation with cinematic formats. By equating their ads with cinema via the letterboxing device, the advertisers imply that their products have merit based on previous consumption of other media (cinema) with similar aesthetic characteristics. Ironically, French New Wave director and longtime Cahiers du Cinema critic Francois Truffaut admitted such intentions when he decided to film The 400 Blows (1959) in CinemaScope. One of the progenitors of the “foreign film cache” associated with letterboxing, Truffaut says, “I had the rather naive feeling that the film would look more professional, more stylized [in CinemaScope]; it would not be completely naturalistic.” (Davis, 1993, 30-34) Truffaut desired a more professional and stylized look that suspended naturalism, and believed that a wider format held such possibilities. Advertisers have those same desires and choose the letterbox format for similar effect. BMW and Buick want nothing more than for their brands to appear as “professional” and “stylized” as possible. Further, the notion of suspended realism is of utmost significance with regard to advertising. Advertisers expect consumers to “buy in” to their constructions of the world within the ad and this will be discussed in more detail with regard to the textual analysis of both Star and Tiger Trap. These spots also have the added dimension of celebrity as Madonna and Tiger Woods star in the BMW Films and Buick spots respectively. The suspension of naturalism — the viewing of Madonna and Tiger Woods performing for consumers — becomes important in the reception of the narrative but only after the denaturalization of the monitor’s mise-en-scene has been achieved via the letterboxing. Video Gaming Aesthetics Thus far, we have discussed a range of options that may account for advertisers’ use of letterboxing with regard to online ads. First, there is the notion of MIVI, which has attenuation as its goal. However, the ads in question are online and therefore must be sought out by the consumer so MIVI cannot be a sufficient reason alone. Next, there is the notion of cultural clout and the association of letterboxing with the “highbrow artistic merit” of quality films. While this idea also is intriguing, it does not explain why advertisers would willingly surrender so much vital visual real estate. Finally, consumers are usually viewing these letterboxed ads on traditional 4:3 monitors via either television or computer monitors. It is here that I think the online content providers have staked their claim. Because online content faces many challenges — different operating systems, monitor sizes, screen resolutions, and monitor widths not to mention download speeds — it seems that the content producers want to achieve MIVI and the panache of letterboxing by colonizing monitor space. In a discussion of the aesthetics of computer window size, Jay David Bolter and Richard Grusin (2002) submit that a:

The implications of Bolter and Grusin’s assessment of the windowed interface is significant. By stating that a windowed environment does not attempt to unify any point of view, the authors point to my characterization of advertisers’ goal in using letterboxing to colonize; by blacking out areas of monitor space, content producers are able to present a focal point, in much the same way as Formalist montage editing. By re-drawing the frame boundaries within a monitor’s visual field, advertisers focus a user’s attention to that which has been colonized and segregated. Therefore, while a user may have a tendency to “oscillate wildly” from window to window, the letterboxed window provides a focal point via its visual separation and segregation. It is here that the online gaming literature becomes more relevant. Gaming, Cut-scenes and Letterboxing If a player of EA Sports’ PGA Championship video arcade game is fortunate enough to “hit” an extraordinary golf “shot,” the aspect ratio of the game’s interface changes from a traditional Academy aspect ratio (4:3) to a widescreen aspect ratio, and more specifically to a letterboxed view. The actual full-screen, 4:3 visual field is thus squeezed vertically to focus the consumer’s attention on the area the interface now provides. The game’s content producers have colonized the visual field so that viewers’ attenuation is directed accordingly. This cinematic flourish is accompanied by an aural heartbeat pounding and slow-motion graphics to further enhance the exceptional quality of the “shot.” With this “cut-scene,” EA Sports is exclaiming visually to the viewer, “Hey, you are no longer a participant, you are now a spectator.” (King and Kryzwinska, 2002, 11) Cut-scenes are narrative events whose importance is usually signified by a shift in the composition of the visual space; an alteration of the frame’s very mise-en-scene. In other words, the widescreen aesthetic is deployed when something extraordinary is taking place which viewers are encouraged to consume. Geoff King and Tanya Kryzwinska (2002) find that the deployment of letterboxing at specific times during game play suggests cues for when players should participate and when they should be spectators. King and Kryzwinska state “the move into gameplay from cut-scenes . . . [is] typically presented in a letterbox format to create a ‘cinematic’ effect…the change in aspect ratio marks a movement from introductory exposition to the development of the specific narrative events to be depicted in the film.” (17) These so-called “cinematics” are visual cues that guide players’ reactions during game play. However, these cues are not always readily appreciated and/or understood. In reviewing EA Sports’ NHL 2002 (EA Sports currently has a virtual stranglehold on the officially licensed sports game market), Dan James Kricke (6/25/02), a fan, notes his dislike for the letterboxing because of its disempowering potential for the gamer. Kricke writes:

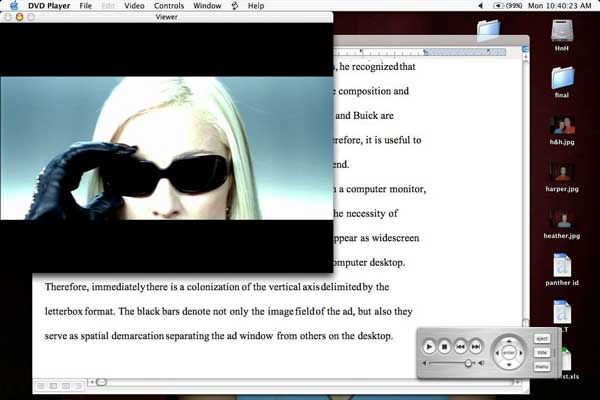

Finally, the notion that letterboxing encourages spectatorship rather than participation is a significant point with regard to online advertisers’ choice of using the letterbox aesthetic. This may seem a revelation given the preponderance of literature regarding widescreen’s lineage with film and its association with “highbrow” artistic media. However, computer monitors are traditionally not used for watching, rather they are used for working. Thus, the letterbox aesthetic transforms the work space into a leisure space. It cues the viewer, via the shift in aspect ratio, that something different is now taking place. Further, because viewers will recognize the letterbox aesthetic as it relates to film viewing, they will be cued via the aspect ratio shift to now consume, rather than participate. I am not suggesting here that consumers of such cut-scenes have no choice with regard to active or passive consuming, but rather that media producers have chosen an aesthetic technique to cue consumers as to appropriate actions. When a cut-scene occurs, players are encouraged to simply consume. Monitor space has been colonized and collapsed and such aesthetics signal to users a shift in behavior is warranted. This last point is significant with regard to advertisers. Advertising is built upon the notion of lack; that is, consumers’ lives lack something, and it is the advertisers’ job to fill that void with their products. Therefore, by prompting viewers to consume via the letterboxing shift, advertisers may have achieved far more than MIVI or the colonization of monitor space; they are attempting to cue consumption. Screen space in Star and Tiger Trap As aforementioned, the use of letterboxing the content of both BMW Films’ ad and Buick’s ad is polysemic. The use of letterboxing is both a hailing device, and also one that signifies a shift to consumption. All of these elements are problematized when viewed upon a computer monitor. When Woody Allen chose to letterbox his films for video release, he recognized that the space of the television monitor must be reconfigured to retain the composition and visual style of his films. Thus, by letterboxing their ads, both BMW and Buick are striving to retain their look regardless of monitor shape and size. Therefore, it is useful to examine how the letterbox space is used in each ad and to what end. Additionally, one must recognize that in viewing these ads on a computer monitor, there will be a variety of competing windows, which further posits the necessity of passive consumption. Regardless of operating system, the ads will appear as widescreen windows among the other windows and/or other applications on a computer desktop. Therefore, when viewing online widescreen texts there is immediately a colonization of the vertical axis delimited by the letterbox format. The black bars denote not only the image field of the ad, but also they serve as spatial demarcation separating the ad window from others on the desktop (Figure 1).

Beyond the aesthetics of the window size on the computer’s desktop, one must consider notions of aesthetic framing and composition that differentiates widescreen formats from the 4:3 format. Ultimately, use of letterboxed formats on traditional 4:3 monitors must be seen as an exploitation and colonization of that space. However, both Charles Barr and Marshall Deutelbaum have noted that widescreen composition involves different framing strategies from that of the 4:3 ratio. Barr notes that directors using CinemaScope allow their compositions to open and “encourage participation” on the part of the spectator. In short, Barr believes that the framing strategies of widescreen formats, specifically CinemaScope, provide a different experience than that of a 4:3 image. Deutelbaum (2003) examined some 100 anamorphic films and determined that although the “photographed elements constantly change; the frame is unchanging.” (73) Further, Deutelbaum asserts that by quartering the frame horizontally, content producers create distinctive framing strategies in anamorphic films. Both Barr and Deutelbaum’s assertions can be summed in the notion of horizontal framing; that is, images across a greater width are composed differently than those that are more symmetrically square and vertical. Thus, the choice of letterboxing for the BMW and Buick ads is again a decision to colonize space and maximize the cue for passive consumption via the scopophilic notion of cinematic treatment of online content. A frame from Star displays this horizontal strategy being used (Figure 2). All of the actors are framed in semi-long shot, and they are spread across the width of the frame thus maximizing frontality. Deutelbaum’s concept of quartering the image is of use here, as the frame appears very balanced across its width. Further, superstar Madonna is centered in the frame, and thus is the focus of the composition. A similar framing technique is evident in Tiger Trap.

Buick’s ad focuses on Tiger Woods confronting unsuspecting golfers and then challenging them to exchange golf shots with him, and the closest shot to the pin wins a Buick SUV. There are many levels of address here regarding consumption and notions of branding and celebrity, however I am chiefly concerned with the ad’s visual style and its use of widescreen. Notice the similarity of blocking in Buick’s Tiger Trap to that of BMW Films’ Star (Figure 3). The actors are arranged across the horizontal axis of the frame, and the depth of field is not utilized. In Buick’s ad, this frontality and the cinematography of the entire text is part of the spectacle. The shoot was done in a guerilla style with camera operators “hidden” all over the course to catch the golfers’ “true” actions. The Buick spot also makes great effort to present multiple perspectives via the use of split screen (Figures 4 and 5). The use of split screen is a more significant justification of the letterbox format than simply just MIVI or a desire for cinematics. The Buick spot is actually less cinematic than is the BMW Films spot because it is self-reflexive. The narrative begins with Woods acknowledging the camera through direct address and allowing the spectator foreknowledge of the plan (to challenge the “unsuspecting” golfers to a competition for a Buick). Therefore, unlike the pure scopophilic spectacle of Star, the Buick ad actually involves a certain level of participation on the part of the viewer. In terms of the video gaming aesthetic where the letterbox discourages participation, the Buick ad encourages participation via both the narrative (Tiger’s address) and the visual style (multiple perspectives and split screen). These multiple screens are all segregated from other windows by letterboxing, and thus again, Bolter and Grusin’s notion of a non-focal windows interface is significant. The producers of Tiger Trap recognize the lack of differentiation within a two-dimensional, windowed environment. Therefore the letterboxing and split-screen aesthetics offer viewers specific and demarcated areas upon which to focus and consume.

Further, the Buick spot is a fractured narrative that involves many “actors” and several different plot lines, whereas the BMW Films’ text is a more traditional, linear and cinematic narrative. However, the differences the two spots possess in narrative structure are negated by the fact that both employ the letterbox aesthetic. Both texts colonize the space of any 4:3 aspect ratio monitor on which they are displayed, but neither has the “imperative” to do so. We are back to our initial question: What does letterboxing mean in online content? Star is a more polished and visually complex text than is Tiger Trap. Star utilizes filters and complex moving camera shots, not to mention a high-speed automobile chase. Tiger Trap on the other hand occurs on a golf course, albeit one with 13 individual cameras and multiple perspectives. However, while Star is a more visually flashy and cinematic text, Tiger Trap demands more attention and participation as Barr suggested is required with widescreen compositions. Barr however was speaking of viewing a CinemaScope film in a theater with an enormous screen, which virtually enveloped its spectators similar to a modern IMAX film experience today. Barr could not have knowledge of modern consumption of online media content. Therefore, is the widescreen aesthetic of Barr’s CinemaScope applicable to Star and Tiger Trap? I posit that it is but on a different scale. Neither ad can compare to the sheer grandeur and size of a CinemaScope film viewed in a theater, nor do they have the imperative to do so. However, by utilizing a letterbox aesthetic, both ads hail their spectators in a similar fashion. Both colonize a spectator’s monitor space and therefore create spectacle via the construction of a barrier between the ad content and the other software applications available on the computer screen’s desktop. Therefore, while CinemaScope was a reaction to television’s 4:3 screen, so is the widescreen aesthetic of letterboxed ads. They command control and demarcation of the desktop space via a visual barrier (masking bars) and thus attempt to harness the spectator’s attention by providing a focal point within an unfocused multi-windowed interface.

What of Kricke’s and King and Kryzwinska’s notions of the shift in aspect ratio? Kricke found the letterbox aesthetic discouraged interactivity in game play, while King and Kryzwinska noted the importance of cut-scenes in terms of cueing gamers when participation was warranted. While there is no physical participation with either Star or Tiger Trap (aside from finding the URL and downloading the content), the shift in aspect ratio and its demarcating effect from other software and/or windows on the computer screen requires some visual attenuation. Again, the colonization of monitor space that takes place when a spectator views this online content embodies the binaries of work vs. leisure and productivity vs. consumption. Computer work space is colonized by the video game or online ad interface — the letterbox masking isolates the work space portion of the monitor from the letterboxed, passive consumption portion that video game and ad producers want viewers to consume. Discussion In this age of digital media convergence, online letterboxed media content that is designed for consumption on a computer monitor’s desktop is an intriguing and significant concept. As our television screens slowly become our computer screens and vice versa, notions of screen space and how media competes for our attention will become more and more important. I do not feel that this essay is sufficient to answer the question of what a widescreen aesthetic choice such as letterboxing means intrinsically. However, in asking how online widescreen content differs from critical approaches to traditional widescreen formats, I feel that this paper serves the purpose of adding to the literature of both film studies and that of online media aesthetics. Certainly, further scholarship in the direction of online media colonizing desktop space and the notions of participation/passivity are intriguing lines of inquiry. I feel the textual analysis herein is demonstrative that letterboxed ad content means more than simply MIVI. The colonization of monitor space provides a focal point within an unfocused media-rich environment. Traditional critical responses of widescreen’s appeal, such as those proffered by Barr, Bazin and Belton, assert that widescreen film formats encourage viewer participation via the lack of edits. Bazin and others prophesied that this lack of montage in widescreen films would create a new kind of cinematic experience — one where the filmmakers did not guide the spectator’s gaze, but rather viewers were liberated and free to roam about the wide visual field. This essay, however, concludes that online content authors utilize widescreen aesthetic choices for quite opposite reasons. The texts discussed here represent a variety of possibilities with regard to the letterbox technique’s ability to cue spectators as to when participation is warranted and/or when consumption is encouraged. Certainly, filmmakers and video distributors have long understood the importance of retaining control of the visual frame regardless of display format. Therefore, it comes as no surprise that advertising and video games have adopted such strategies to attempt to guide consumers’ attention. More significant, but subsequently more nebulous, is the binary of active vs. passive consumption and the use of letterboxing to encourage one state over the other. When online content producers make the decision to present a colonized visual field, they are attempting to engage consumers’ visual attention. As aforementioned, video gamers may participate during the course of game play, but cut-scenes cue gamers by the alteration of available screen space to set down their controllers (literally surrendering control) and consume the “cinematics.” Similarly, when a consumer engages the video interface of either Star or Tiger Trap, they surrender their control over their monitor’s screen space to the colonization of the advertising content. As consumers then, advertisers have a mode of production by which they may cue us when to consume by controlling the visual fields we gaze upon. I am not suggesting a magic bullet with regard to widescreen’s ability to cue an active vs. passive state; however content producers understand that letterboxed visuals mean something different than traditional 4:3 ratios, and this essay is simply one step in discovering what those meanings are and how they are communicated. References Barr, Charles. “CinemaScope: Before and After,” Film Quarterly 16, no. 4 (Summer 1963). Belton, John. Widescreen Cinema. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1992. Belton, John. American Cinema/American Culture. New York: McGraw-Hill, Inc., 1994. Bolter, Jay David and Richard

Grusin. Remediation: Understanding New Media. Bordwell, David. “Widescreen Aesthetics and Mise En Scene Criticism,” Velvet Light Trap, no.21 (Summer 1985), 118-125. Davis, Helene Laroche. “Reminiscing about Shoot the Piano Player.” Cineaste. Mar93, Vol. 19(4), 30-34 Garfield, Bob. “Innovation boxes out effective approach in Mercedes-Benz ads.” Advertising Age. 5/11/92, Vol. 63(19), 77. King, Geoff and Tanya Kryzwinska. Screenplay: Cinema/videogames/interfaces. New York: Wallflower Press. 2002, 17. Kricke, Dan James. (06/25/2002). NHL 2002 review. http://www.gamepartisan.com/sony/reviews/index.php?view=38 Truffaut, Francois. “En avoir en plein la vue.” Cahiers du Cinema, no. 25(July 1953): 22-3. Vagoni, Anthony. “Out of the box.” Advertising Age. Vol. 70(46), 11/08/99, 48-50.

|

|||