The Plane of Mediation:

The Actual and Virtual as Cultural System

(pdf version)

Michael Filimowicz

Simon Fraser University

Abstract

This paper proposes a new synthetic model of culture as a dynamic system of negative-virtuals and positive-actuals called the plane of mediation, which can serve strategies of transdiscursive inquiry across humanist and social science disciplines. The paper starts from the notion of Auerbach’s hermeneutic handle as a means by which interpretive methodologies can aspire to empirical rigor, and complements this notion with the phenomenological technique of imaginative variation. The plane of mediation reconfigures the individual, the social and the cultural as system positions in a manner that integrates postpositivist and social constructivist knowledge paradigms. Culture is thus configured as the space of virtual-actuals or actual-virtuals whereby Society can work out its transformations in advance.

Keywords: hermeneutics, Auerbach, phenomenology, imaginative variation, culture, society, mediation, actual, virtual

The Plane of Mediation

[I]n order to accomplish a major work of synthesis it is imperative to locate a point of departure [Ansatzpunkt], a handle, as it were, by which the subject can be seized. The point of departure must be the election of a firmly circumscribed, easily comprehensible set of phenomena whose interpretation is a radiation out from them and which orders and interprets a greater region than they themselves occupy.

- (Auerbach, 1969, pp. 13-14);

1. Handles and Diagrams

This essay, while not offering anything like the “major synthesis” suggested by Auerbach in the epigraph, is a first attempt to disentangle two words often used synonymously in discourse: “society” and “culture” and their variants, “social” and “cultural.” These two concepts are of course similar, possess overlapping affinities and discursive halos, while at the same time providing disciplinary bearings for distinct and variously rigorous forms of inquiry, e.g. sociology and cultural studies. Auerbach’s notion of a handle is a useful one, and I will try to use it here:

Figure 1: virtual and actual murder

What this figure– a composite of two files culled from Google Images– tries to provoke is the specific difference between virtual and actual murder. On the left is a screenshot from a video game, and the right frame shows a typical newscast report of the arrest of a suspect in a murder investigation. Since the two terms “social” and “cultural” are often synonymous with each other in discourse, and so slippery or tricky to disentangle, we need a handle, and this seems to be a good one (real vs. actual murder), a “great place to start” so to speak, since we can immediately align “the social” with the image on the right – the social process of identifying a suspect, police forces, laboratory evidence, court proceedings, in short, all that we would normally mean by Society in this kind of situation – whereas the image on the left is clearly a piece of Culture, as the murder is NOT real but virtual, occurring in an imaginary zone of action that does not call forth the forces of Society but does of course mobilize industries of cultural production which produce these kinds of virtual cultural objects, such as video games, films, books and so on where murder or anything else, because of its virtuality, is contained or sanctioned or cordoned off from the real in some way.

With respect to a “real” murder, Society calls up its forces – the physical forces of state violence approximate the real forces of nature. On this basis I will offer a provisional definition of society and the social: practices and institutions that influence or determine dispensations of the real. This is “society proper,” social forces as concretized by material and legal supports, formally organized methods, procedures and personnel that are put into action to find “the real” culprit of actual murder and thus satisfy the demand for tracing the effect back to its cause, the perpetrator behind the crime.

For present purposes I will define a ‘practice’ as an ‘informal institution’ and an ‘institution’ as a ‘formalized practice.’ Where are these definitions coming from? They are both suggested by the handle itself– the practice of sitting at home and playing a video game, versus all the social institutions activated by a murder case– but I have also relied on the intertextual field somewhat, my past readings of sociological and anthropological texts whose titles and authors escape me, and are just part of my general understanding of how society works. To quickly sketch the difference between a practice and an institution: a practice is something like a young person practicing guitar in their bedroom, supplemented by lessons at the neighborhood music store, while an institution is something like a music conservatory offering degrees, formalized and programmatic training. It is a basic enough distinction that for now we can leave out extensive citations. In the literature on these sorts of topics, some have argued that society was basically composed of practices until the invention of writing technologies provided effective means of formalization for institutions, or that oral cultures lacked what we call institutions but had elaborate forms of practice that gave formal shape to the society. With respect to the example of murder, the police are the formalized institutional response, but a spontaneous neighborhood vigilante party would be more like a practice.

While a Society typically has very strong sanctions and forms of control against non-State violent actors, in video games murder is often the whole point. It is properly ‘cultural’ because it does not set into action the state apparatus with each kill. It is a cultural object, an industrial product, a zone of meaning and meaningful artefact that “isn’t really real.” So it is better understood not as ‘the virtual’ but rather as a mix of the actual and virtual. Its actuality is as a concrete and specific form of mediation (audiovisual interactive narrative in this example of a video game) but performatively virtual (no one really gets hurt).

Since Society mobilizes the Actual (real forces), and the Cultural seems to mix forms of actuality (a medium) and virtuality (make believe stuff), we seem to be in need of a relatively “unmixed” virtuality (at least for conceptual clarity, to continue the exercise of abstraction in a productive direction). “Pure” Virtuality, it can be suggested, would be in the imagination of any particular Individual. Virtuality in this sense is not embedded in actualities (cultural objects or products – books, paintings, computers, clothes etc.) other than the person. A cultural object like a video game requires meanings to be bound to actuals– screen, controller, console, DVDs– in circulation of some kind, whereas Virtuality needs no other materiality than what is internalized in the mind, in what we imagine, not bound to external objects in any way, but situated within ourselves, and only becoming Cultural (actual-virtual mix) when mediated: spoken, written, spammed, hacked, played, enacted etc.

This might seem to in some way “displace” the notion of Culture from the minds or even the “brains” of people, but since Culture has already been defined as the mix of the actual and virtual (virtual meanings attached to real things), this is not really the case. Likewise, no one would confuse the concept of culture with only the material support of it (e.g. the plastic in a DVD, the rock in a stone wall, the cotton plant in a sock, etc.). As the above reflections are amenable to summary in a diagram, I will outline the preceding thoughts as so:

• Society (Actual): practices and institutions that influence or determine dispensations of the real

• Culture (Virtual-Actual): bounded forms (the Actual) of meaning (the Virtual) in circulation

• Individual (Virtual): unbounded meaning, non-circulating and unmediated or immediate meaning

Recalling Bourdieu’s concept of hexis, nothing in the above sketch denies that an Individual could, for instance, embody and perform cultural meanings in their very gait or posture, in short, perform culture through the internalized or patterned habits of the body: “Bodily hexis is political mythology realised, embodied, turned into a permanent disposition, a durable manner of standing, speaking and thereby of feeling and thinking.” (Bourdieu, Web). The body can be a medium, and in the performance of its routine acts binds its meaning to itself, in effect becoming the actual of the virtual meaning in circulation. Also, with regards to the distinction to be made between real and virtual murder, that distinction is of course made both at the level of the Social– legal and illegal forms of real and virtual murder– and the Individual, who can tell the difference, at least presumably and usually, if not hopefully. So our “stratified” vertical representation also works as a horizontal spectrum:

Actual/Social ---> Virtual Actuals/ Culture <--- Virtual/Individual

We have got this far in reconceptualizing these terms on the basis of a single Auerbachian handle. In phenomenology there is the technique of imaginative variation, in which varieties are brought forth for consideration before intentional consciousness in order to locate or define an invariant.

One can access this content of noema and noesis through reflection. So, if I am interested in knowing how people are aware of a 'mobile phone ' I have to consider certain examples of this experience. These experiences cannot be called purely phenomenological, because a purely phenomenological experience is purely mental. However , this purely phenomenological is always embedded in the concrete space time time events , therefore search for the purely phenomenological starts from these experiences. Once we have studied some examples , we can imaginatively vary the experiences in our minds….This step is called imaginative variation….During these imaginative experiences I try to change certain details and see what is that which remains self same in all the variations….This is called determination of essences , or eidetic reduction. (Methodspace, Web)

We can further “test” the hypotheses above through imaginative variations. Below are two contrasting images from differing kinds of social protest (obviously hundreds of similar images could be utilized, but two suffice for the point being made):

Figure 2. Photos of two social protests

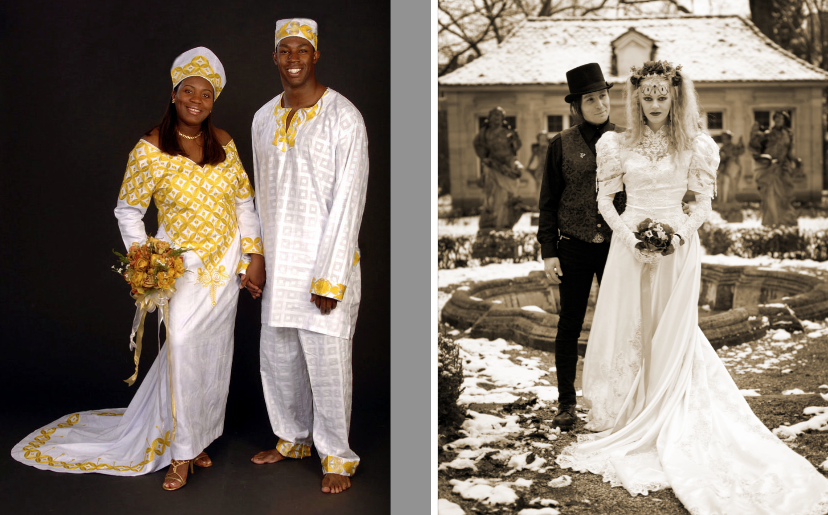

The invariant in the images above are the social relations, which are identifiable as more uniform and of a stability different in character from the virtual actuals of dress, props and signage. The invariants can be described generally as follows: a collective forward-movement and frontal assemblage of a crowd; a rhythm of upraised arms and clenched fists; mouths open in loudly vocalizing chants, slogans or songs; taking to the streets and blocking vehicular traffic, a gesture of interrupting the day-to-day routines of normality; camera-friendly dispositions (the wish to communicate the message beyond the scene); a self-to-crowd gradient, with individual members more-to-less “into it” as shown by some bemused or detached individuals in the crowd. This is a general form of social protest found around the world, perhaps somewhat stabilized from the circulation of images as to how these kinds of social protest acts are to be performed. Imaginative variation can be performed on any number of social formations. Here are other photographs from Google Images, of two heterosexual weddings:

Figure 3. Photos of two wedding ceremonies

Again, the social relation seen here is more or less invariant, while the differences between these African and Gothic weddings pertain to actual-virtuals, primarily through dress and makeup, though with some interesting similarities (in both, the bride carries the bouquet, albeit either single or two-handedly). Social organization mobilizes the real – in the case of marriage, perhaps the incomes of two persons will combine to afford the mortgage on a more desirable home than a single income alone can provide; with political protest, perhaps politicians will be put on notice or a debate stirred on a law or policy and so forth. In these images that which varies the most are what I am calling actual-virtuals or virtual-actuals, e.g. a fire extinguisher painted white and labeled “SPERM” in a Gutenberg Gothic script, or a groom posing for his wedding portrait shoeless. These actualities mobilize cultural virtualities. As to exactly what any depicted person is thinking at the time of these photos, that would be “pure” virtuality, since we lack telepathy. Even if someone is shouting a slogan in a parade, they may actually be thinking that they are cold without clothing, or wondering what to cook for dinner. So the imaginative variations allowed by phenomenological inquiry, mediated here through Google Images, support the initial conceptual terrain that was derived from the example of video game versus news report murder. I have used the terms Actual and Virtual here in a rather “off-the-shelf” manner, as handles as suggested by Auerbach. It is worth recalling other discourses that have used this terminology:

Every actual surrounds itself with a cloud of virtual images. This cloud is composed of a series of more or less extensive coexisting circuits, along which the virtual images are distributed, and around which they run. These virtuals vary in kind as well as in their degree of proximity from the actual particles by which they are both emitted and absorbed. (Deleuze and Parnet, 2007, p. 149)

In Reading Voices, Garrett Stewart argues that literary language is literary in part because of its ability to mobilize “virtual” words – related by sound, sense, or usage to those actually on the page – that surround the text with a “blooming buzz” of variants enriching and extending the text’s meanings. (Hayles, 2005, 53)

Of course, there are some works that are still being exploited commercially long after their publication date. Obviously the owners of these works would not want them freely available online. This seems reasonable enough, though even with those works the copyright should expire eventually. But remember, in the Library of Congress’s vast, wonderful pudding of songs and pictures and films and books and magazines and newspapers, there is perhaps a handful of raisins’ worth of works that anyone is making any money from, and the vast majority of those come from the last ten years. If one goes back twenty years, perhaps a raisin. Fifty years? A slight raisiny aroma. We restrict access to the whole pudding in order to give the owners of the raisin slivers their due. But this pudding is almost all of twentieth-century culture, and we are restricting access to it when almost of all of it could be available. (Boyle, 2008, p.12) [emphasis mine]

This last citation, from James Boyle’s The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind, while not employing the terms ‘actual’ and ‘virtual’ uses the actual virtuality of metaphor – a raisin pudding of some kind – to signify what the author describes as “most” of 20th century culture. How it comes to be that a raisin pudding can symbolize all of 20th century American culture, I will just leave to any reader’s imagination. For our purposes, it is important to note that what Boyle means by ‘culture’ is not something like a system of rules or behaviors inside the minds of people, e.g. a ‘worldview’ such as might have been found in Johann Gottfried Herder (period of German Romanticism): “Culture is that attitude towards the world that reveals the soul of the people. It is mirrored in their artistic expressions and in particular in their poetry.”(Herder, 1773, Web). Nor is culture identical to the Library of Congress, which is a State institution that has locked up culture through copyright laws, i.e. a big government building ultimately backed up by the rule of law and a military that in turns backs that up. Internalized memes in the mind, and State social apparatus, are nonidentical to what Boyle indicates by culture. Culture in his sense is what in this essay I am calling the plane of mediation – the circulation of virtual actuals, bounded forms of meaning– what Boyle identifies as “songs and pictures and films and books and magazines and newspapers” and so on.

The concepts of Actual and Virtual employed in the first two citations are redolent of their usage in the handle and the imaginative variations above, as well as the sketched relations derived therefrom. The use of these Auerbachian handles – readymade, concrete phenomena that exhibit clear whole-organization and a boundedness in their manner of appearance, similar to what a “case” is in a case study, impart the potential of empirical rigour to hermeneutic method. This leads to what Auerbach identified as the possibility of synthesis across disparate domains. Diagrams, bullet points, diptychs or tables, however, are somewhat static visualizations. These concepts are in need of dynamic modeling.

2. The Car Battery Model of Culture

In this section I will further vary the diagrammatic outlines above and provide a heuristic of a more dynamic system. A car battery will suffice, since it is easier to imagine as a dynamic system than, say, a raisin pudding. A basic tenet of systems theory is that all systems possess similar properties that make them describable as systems in the first place. From this it follows that we can find properties in one system and map them onto another by way of analogy. Systems theory itself is the science of discovering analogies across systems.

Research in the use of analogies in science and technology during the last two centuries reveals that, besides the striking successes of applications of these analogies, there are also dramatic failures, not to speak of sophistic misuses, in the logic of reasoning.(Hezemans and van Geffen, 1991, p. 170)

In the social sciences, debates around the status and applications of systems methodologies have been based on whether systems models are to be considered as metaphorical descriptions of reality or ontological structures thereof. In this context, hopefully it is clear that my appropriation of a car battery is of a metaphoric instance.

In the absence of a deliberative discussion on this reconciliation, research on self-organizing systems in the social sciences runs the risk of being either (i) overwhelmingly metaphorical (some would argue “hand waving”), or (ii) an unenlightened and inappropriate attempt at importing models and theories from the physical and life sciences to the study of social phenomena. Both of these outcomes were evidenced in the arguably unsuccessful attempt by scholars in an earlier era to appropriate open systems theory into the social domain. (Contractor, 1998, 2)

Keeping in mind the rather chequered past of applying systems theory to the social and human domains, I have chosen a car battery because it is a relatively simple system (thus, a good handle), and like the plane of mediation described above, a car battery also has two poles, called positive and negative rather than actual and virtual. The entire domain of organized knowledge also has positive and negative poles. Scientific methodological paradigms are known as “postpositivist” in the literature on research designs (e.g.Creswell, 2007) – this paradigm, postpositivism, studies what is “actually real” so to speak, independent of our socialized interpretations. On the humanities side, “social constructivism” prevails as the dominant mode of inquiry, while the social sciences mix qualitative and quantitative methods. We can align the constructivist perspective with the negative pole of our car battery model for fairly straightforward reasons: the constructivist perspective takes as axiomatic the notion of sign systems organized through negative differences. That is, meanings– significations– are understood as relational (negative, relative to each other), not “positive” in the manner of scientific inquiry, which postits actual real sgnifieds or referents independent of the sign system.

It is helpful to compare these knowledge paradigms, via the logic of analogy, with both the car battery system-image and the plane of mediation, because the social was defined above as practices and institutions which control or influence “dispensations of the real.” The social structure organizes positive reals (food, land, bombs, money, police force, vaccines, famine relief, etc.). Social force is based on real forces, e.g. bullets have more in common with physics than video streams of Madonna on YouTube etc. How these simple symbols from mathematics, - and +, indicating either more than (+) or less than (-) zero ended up migrating to a general metaphysics of knowledge in which negativity ultimately gets paired with “social construction” and positivity paired with “scientific truth” is beyond the current scope of the present endeavor. It is a suspicious situation, but it is there to be seen in the very organization of the university itself, particularly on the bookshelves of university libraries in the research methodology section! Here it is being mapped, by way of analogy with systems metaphor, onto a car battery:

Figure 4. Analogy with systems metaphor onto a car battery

It is also a pragmatic-looking model (car batteries are useful entities), and suggests that cultural mediations oscillate or circulate between poles of personal individuation– e.g. reading

Moby Dick on my porch for self edification or enjoyment, to build the autonomy of my imagination, my personal virtual worlds – or towards social impact or maintenance– reform, revolt or reinforcements of the status quo. Of course there is quite a lot of “middle ground” between these two poles– the large black box in between– where we would expect to find forms such as televised sitcoms that aim to entertain the one without offending the many. The car battery model offers a way in which the cultural and the social and the individual can be disentangled or distinguished from each other as system positions. Also, it allows a corrective distance from the social in which individual enactments and agency can be situated, given the preponderance of media and cultural theorizations that undermine human agency in general, as in structuralist or Marxist base/superstructure accounts of social reality, or the decentering of subjectivity found in the linguistic turn, to give two prominent examples. It also happens that the alignment of the individual-virtual with the notion of the negative dovetails nicely with interesting parallels in humanist discourses, for instance Keats’s notion of “negative capability”:

Negative capability describes the capacity of human beings to transcend and revise their contexts. “I mean Negative Capability, that is, when a man is capable of being in uncertainties, mysteries, doubts, without any irritable reaching after fact and reason.” (Negative Capability, Web)

The negative pole in the car battery model leaves the cultural realm open to the fact that anyone can imagine it otherwise, and can produce actual-virtuals (mediations, materially bound forms of meaning) that go into circulation. We can also understand this Negative Individuality as having affinity with or being akin to Bartelby’s statement “I prefer not to” or Adorno’s concept of “nonidentity,” to mention to other well-known associations of individuality and the imaginal with the negative in general. Taking these three examples together (Keats, Melville, Adorno), this individual negativity articulates the disparity between the real and the concept, the general ability to imagine things other than as they are, the potential to refuse participation, and the ability to dwell in deep uncertainty.

In the creation of cultural forms – bounded and circulating forms of meaning– this negativity is mixed with positive actual concretes– materials, technologies, performances, rituals, plastic, pixels, etc. The social is positive because it organizes real materials, spaces and resources that it applies actual physical forces to in order to organize the positive stuff of the world into technologies, built environments and media. Society is indissociable from physics– it has forces that organize the materials and energies of the universe, even commanding nuclear and quantum forces. All laws of nature are identical (positive), which is what makes them laws (constants, repeatable, capable of predictive calculations). Society dispenses the real (paycheques, food, status, property, technologies, prisons) and generally demands not the individual’s “personal take” on the situation, but rather typically presses the individual, through its mediations, toward various conformities– social identities coordinated with dispensations of the real that are physical identities. These are the kinds of theoretic generalities that are explainable or mappable by the car battery model of mediation, presenting a graspable and dynamic system of individual-cultural-social interaction.

3. Offload to Reload

The plane of mediation suggests that culture can be conceived as the plane whereby societies work out their transformations in advance, or at least their possibilities for transformation. In our own time, for example, we can track the gradual cultural acceptance of both gay marriage and marijuana use as being prefigurative of changes to social law (organization of the real).

Figure 5. Anti-gay marriage picketing, film poster

Figure 6. Marijuana legalization media, Cheech and Chong

Culture, as actual-virtuals, can mobilize with much less “drag of the real” than anything social. Laws are virtualities as well – ink on paper like anything else that can be textually imagined – but laws are different from circulating culture because they are wired directly into force, the social mobilization of the real. Sociologist Anthony Giddens, in his highly influential theory of structuration, attempted to create a conceptual balance between human agency and social structures of opportunity. Yet Giddens’ conceptualizations of the virtual social order – that each of us internalizes as patterns and externalizes through actions –tends to argue that social structures are maintained because people keep believing in them. His conception of social structure is:

[A] ‘virtual order’ of transformative relations...that exists, as time-space presence, only in its instantiations in [reproduced social] practices and as memory traces orienting the conduct of human agents. (qtd in Jones and Karsten, 2008, p. 131) [emphasis mine]

Giddens appeared to lack a notion of the ways in which the the organization of the real in itself can have a kind of agency. For example, what makes my home my property is not just what I imagine, not only what is in my head, but also what is built into the material structure of my neighborhood– I have locks on my doors and windows, an alarm system, perhaps an anti-social dog, watchful neighbors, and the police will come if I report an intruder. Every two weeks my paycheque shows up in my bank account which helps with paying the mortgage, and there is little cognitive effort expended, on behalf of either myself or my employer, to make any of these things so, because we precisely build our beliefs into our surroundings, our material culture– in short, we automate our cognition through organized technologies. Again Giddens writes,

The causal effects of structural properties of human institutions are there simply because they are produced and reproduced in everyday actions. Technology does nothing, except as implicated in the actions of human beings. (qtd in Jones and Karsten, 2008, p. 131).

Giddens somewhat overlooks or elides the fact that we design technologies to relieve of us of our actions, and to automate our cognitive effort so as to be unbothered by it. It is not that he is completely incorrect that technologies are implicated in social structure through human action, but his weak understanding of what in actor network theory is understood as the agency of the technical overlooks the fact that we authorize technology to think and act on our behalf. We offload and disperse our actions and mental efforts into the built environment, where they continue to act and think for us, with very little input from our explicit actions. In short, Giddens overlooks the character of the virtual order that is ambient, on autopilot as it were, “deputized” in agential relations to us. Here “agential” does not mean a notion of the inherent agency of machines, but is meant rather in the legal sense – as in a real estate agent – authorized to act for us within narrow parameters. Thus Giddens conceives the “virtual order” in somewhat dematerialized terms. He lacks an account of what is actual about it, other than memory traces and behaviors.

For another variant of the “it’s all in our head” thesis– what Felix Guatarri named “psychoanalaytic reduction” in Chaosophy (2008)– we can consider Benedict Anderson’s notion of “imagined communities”:

In an anthropological spirit, then, I propose the following definition of the nation: it is an imagined political community – and imagined as both inherently limited and sovereign. It is imagined because the member of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion.(Anderson, 1982, pp. 8-9)

In this classic definition, which has been highly influential humanities discourses, the ground shifts almost entirely toward psychoanalytic reduction, as the “turf” so to speak of national identity is here understood strictly in relation to a notion of “imagination.” But works of the imagination, whether a sense of national identity or a work of art – typical concerns of the humanities– are not purely virtual and imaginal entities. They are environmentally inscripted, agented and automated into the very texture of the real that is our built and social context. Again, copyright discourse is here helpful in rematerializing the virtualities that often tend too easily toward imaginal virtualization in humanist inquiry. Writing of the physical containers of musical objects, Lewis Hyde writes, “When concrete objects deliver abstract objects, a skin of scarce and exclusive property settles over the abundant and nonexclusive, stands in its stead, and makes it easy to manage a right-holders’ privileges.” (Hyde, 2010, pp. 63-64). Here, the musical object is described as containing a second layer or halo of virtuality – in addition to the virtualities of musical production, imagination, history, aesthetics and so on, is the legal virtuality of copyright protection, which is tied to all the apparatuses of the socially real, which in turn are bound to physical force and the forces of physics. Hyde also depicts this actual-virtual layering or mixture as not just bound to objects, but dispersed as ambient environment:

The public domain surrounds us, but almost invisibly so, as if it were the dark matter in the universe of property. To illuminate but one case in point, every time you drive your car to work, you unwittingly take a ride on the public domain. Exactly how many inventions of the human mind are bundled in a working automobile? (p. 47)

The individual imagination, I have argued above, is the place of Negative Virtuality – the “problem” for the concepts of imagined communities or structurational virtual social order is that we build these communities and orders as material systems of virtual-actuals, precisely so that we don’t have to perform the work of imagining them, to relieve ourselves of the cognitive labor of doing so. What gets overlooked is the fact that imagination requires cognitive work to be done, and we precisely build the real around us so as to offload that cognitive labor into the real-at-large. In this respect, variations of psychoanalytic reduction– the “it’s all in our head theories”– are perhaps a bit to 18th century and Romantic in tonality (recalling Herder’s concept of culture as being in the “soul” or minds of people).

When we offload we reload, in fact we offload to reload. Cooking, for instance, digests our food outside our bodies, which beginning with the invention of fire freed up more metabolic energy for cognitive development – energy that the belly didn’t need went to the head instead. As the title of an online article at Smithsonian.com puts it:

Why Fire Makes Us Human

Cooking may be more than just a part of your daily routine, it may be what made your brain as powerful as it is. Smithsonian, Web)

In an energetic economy – an economy of finite energy – work offloaded or externalized frees up energy to be redistributed and used in some other manner. Eric Havelock has argued that the invention of the Greek phonetic alphabet freed the mind from the effort of practicing memory – always having to recall the texts of oral tradition by rote – and in effect freed up cognitive space to develop new forms of ideation that had been constrained by the cognitive effort of always having to recite:

The alphabet, making available a visualized record which was complete, in place of an acoustic one, abolished the need for memorization and hence for rhythm. Rhythm had hitherto placed severe limitations on the verbal arrangement of what might be said, or thought.More than that, the need to remember had used up a degree of brain power – of psychic energy – which now was no longer needed. The statement need not be memorized. It could lie around as an artifact, to be read when needed. No penalty for forgetting….The mental energies thus released, by this economy of memory, have probably been extensive, contributing to an immense expansion of knowledge available to the human mind.(1982, p. 87)

Technologies of writing offloaded memory to the codexes and bookshelves, freeing literate humans from the need to practice recitation, which in turn freed up the mind for new forms of thinking, aided in turn by the new technologies of writing. Culture, as an energy economy, is the production of virtual actuals that allow us to offload to reload, and one capability that gets reloaded is the capacity to produce ever new orders of actual-virtuals. This is what is overlooked by the variants of the “it’s all in our head” theories – psychoanalytic reduction, imaginary community, memorized virtual orders, what have you – over millennia we have offloaded our cognition and meanings into the built environment, which does much of our thinking for us, and has been designed to do so. For instance, I can drive to work, 40km away from my home, rather easily, since only a small handful of specific street names and turns are required– this frees my mind to enjoy a shuffling playlist on an iPod or, if I am a callous and antisocial driver, to send text messages at some risk to others. This offloading of cognitive effort through technologies that environmentally disperse information has been documented in psychological studies that have investigated mental labor in relation to the effects of the internet on knowledge recall. In their study of Google as a transactive memory system– memory configured outside ourselves but socially and spatially at hand– Sparrow et al have found:

Overall, in answer to the question “Was this statement exactly what you read?” participants recognized the accuracy of a large proportion of statements. But for those statements they believed had been erased, participants had the best memory. (2011, p.777)

In other words, with respect to the mental effort required to better remember information– known as rehearsal in cognitive theories of memory– less cognitive effort was expended when information was considered to be available in local storage systems, while more effort was expended to produce better recall when the information was believed to be unavailable to participants beyond their own memories.

It is not possible to expend an amount of cognitive energy required to continuously imagine all that is entailed by self, nation, identity, modernity, socialization, knowledge, citizens, workers, game players and so forth. The cognitive energy load is dispersed into material culture, to support institutions and practices through the circulation of actual-virtuals that embed not only meanings but the very labor or energy expenditure of imagination, the virtual order itself.

We are not beings in the world – we are beings in a world on the Earth. While the Earth and its Universe are pure positivities, the world is virtual-actual, thoroughly built up around us with our meanings and automated actions externalized and embedded into the very concrete and wiring of things. Even in less materialy developed societies this appears to be the case, since animism can be understood as a form of ambient virtuality situated in the forms and affordances of the natural environment itself, even when relatively unaltered.

In the open and semi-virtual space of circulating culture, we can change ourselves and our society. As well, another possibility – society can push its programs of maintenance, and we can solipsistically withdraw from considerations of how the real is organized by practices and institutions. No doubt all of these happen at once in a dynamic flow of positive-negative mixed-up actual-virtuals.

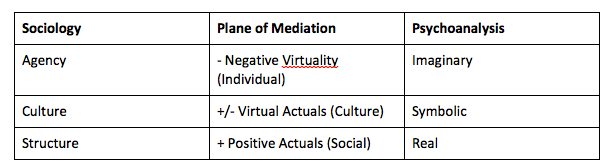

Below, what I have called the plane of mediation is reconfigured once more, this time as a disciplinary heuristic, synthesizing a new matrix of unified transdisciplinary inquiry. In more recent sociological scholarship– for instance that of Margaret Archer or David Rubinstein– “culture” has emerged as a third term moderating and mediating traditional debates in the discipline as to the relative “primacy” of social structure over and against forms of human agency. Here I have mapped the plane of mediation as a link between what can be configured as adjacent discourses, in order to give a sense of the kind of interdisciplinary or transdisciplinary maneuvers and possibilities that can emerge with a new model of culture as a dynamic system of negative imaginary virtualities and socially positive actualities. In the chart below, the plane of mediation also links to psychoanalysis, where I have made explicit connections to Lacan’s well-known semiotic triad:

Table 1: transdiscursive possibilities

The car battery metaphor systemically configures culture as a plane of mediation with two conduits for circulation: 1) the pole of positive actuals – the real as organized and distributed by social action; and 2) the pole of negative virtuals, the whole-organized mind of any individual, virtual psychic space.

To be sure, media theory has been figured before as a kind of meta-discourse having the potential to unify any and all disparate forms of human and social inquiry:

The study of communication...is in an undecided, and perhaps undecidable, state with regards to its significance for the human sciences. In one respect, it appears as a specialized area of investigation which, although it has its own internal issues and perhaps even classics, is distinguished more widely primarily by the fact that it is a latecomer to the academic division of labor compared to sociology, anthropology, political science, or psychology. In another respect, it is often proposed as a synthetic approach to the human sciences outright, an interdisciplinary inquiry capable of linking the researches of specialized human sciences to the philosophical foundations of the project of human scientific inquiry itself.(Angus, 2000, p. 38)

The interdisciplinary table mapped above proposes not so much a synthesis of disciplines but something more like a transdiscursive strategy, a new articulation of media and cultural studies perhaps, to be taken up as needed and as useful in research and creation. I propose this transdiscursive space via a focus on the plane of mediation as a dynamic system productive of cultural formations emerging from real and virtual system positions.

It is a tradition of circuit diagrams to represent the flow of electrons as moving from the positive to the negative pole through a graphical representation called “conventional flow notation”. However, this convention exactly reverses the truth. In fact, electrons flow from the negative to the positive poles, and are shown otherwise only because of the popular perception that a positive pole should be an origin and a surplus. In other words, while it has not been the preconceived intent to do so, the car battery model of culture appears to completely invert the base-superstructure model provided by 19th century political economy (Marx), putting the organization of the real entirely in the flow of surplus imagination. Food for thought, if only to return to the raisin pudding metaphor.

Figure 7. Circuit diagram showing the actual movement of electrons

References

Anderson, Benedict (1982). Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism. London and New York: Verso.

Angus, Ian (2000). Primal Scenes of Communication: Communication, Consumerism, and Social Movements. SUNY Press.

Auerbach, Erich (1969). Philology and Weltliteratur. The Centennial Review. 12(1), 1-17.

Boyle, James (2008). The Public Domain: Enclosing the Commons of the Mind. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Accessed online: http://scholarship.law.duke.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=5385&context=faculty_scholarship

Contractor, Noshir S. (1998). Self-organizing systems research in the social sciences: Reconciling the metaphors and the models. Paper presented at a joint session of the Organizational Communication Division and Information systems Division at the 48 Annual Conference of the International. Communication Association, July 1998, Jerusalem, Israel. Preparation of the manuscript was supported by National Science Foundation Grant No. ECS-94-27730.

John Creswell and Vicki L. Plano Clark (2010). Designing and Conducting Mixed Methods Research. (2nd ed.). Sage.

Deleuze, Gilles and Claire Parnet (2007). Dialogues II. Columbia University Press.

Guattari, Félix (2008). Chaosophy: Texts and Interviews 1972–1977. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press.

Havelock, Eric (1982). The Literate Revolution in Greece and Its Cultural Consequences. Princeton New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Hayles, Katherine (2005). My Mother was a Computer: Digital Subjects and Literary Texts. University of Chicago Press.

Hezemans, Peter M.A.L. and Leo C.M.M. van Geffen (1991). Analogy Theory for a Systems Approach to Physical and Technical Systems. Qualitative Simulation Modeling and Analysis

Advances in Simulation, 5, 170-216.

Hyde, Lewis (2010). Common as Air: Revolution, Art and Ownership. New York: Farrar, Strauss, and Giraux.

Jones, Matthew R. and Helena Karsten (2008). Giddens’s Structuration Theory and Information Systems Research. MIS Quarterly 32(1), 127-157. Accessed online 3 Oct. 2013.

Sparrow, Betsy, Jenny Liu and Daniel M. Wegner (2011). Google Effects on Memory: Cognitive Consequences of Having Information at Our Fingertips. Science, 333, 776-778.

Web Cited

Bourdieu: http://enfolding.org/theorising-practice-ii-habitushexis/

Johann Gottfried Herder: http://www.unibas-ethno.ch/redakteure/foerster/dokumente/Culture20080228.pdf

Methodspace: http://www.methodspace.com/profiles/blogs/phenomenological-research

Negative Capability: http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Negative_capability

Smithsonian: http://www.smithsonianmag.com/science-nature/Why-Fire-Makes-Us-Human-208349501.html#Mind-on-Fire-cooking-evolution-1.jpg

Figure Sources

Figure 1: Image 1, Image 2

Figure 2:

Isreali protest, Gay Marriage

Figure 3: Gothic Wedding, African Wedding

Figure 4: Car battery

Figure 5: Image 1, Image 2

Figure 6: Image 1, Image 2

Figure 7: Circuit diagram

Michael Filimowicz is a multi-disciplinary artist working in the areas of interactive media, experimental video, sound art, digital photography and creative writing. He is currently pursuing an interdisciplinary degree in Information Semiotics through SFU's PhD by Special Arrangements program. He is also founder of Cinesonika, the annual international festival and conference of sound design, and co-editor of the academic journal, The Soundtrack. He teaches at the School of Interactive Arts and Technology at Simon Fraser University in Vancouver, British Columbia.