Skip to Navigation Skip to Content Skip to Footer Navigation

HENRY P. MILLS

Henry P. Mills is founding director and editor of The Walker Percy Project. He completed his graduate studies at Louisiana State University, where he was introduced to Walker Percy's writings.

Go to: The Project's section on Walker Percy's Semiotics

An Initial Query

On the subject of his semiotics, Percy once remarked in an interview:

"I have never and will never do anything as important. If I am remembered for anything a hundred years from now, it will probably be for that" (Southern Review, Vol. 20, No. 1, p. 94).

The Aim of this Essay

The following essay introduces the reader to the fundamentals underlying Percy's perspective as found primarily in his Message in the

Bottle (1975) and Lost in the Cosmos (1983) and takes the following route: As it is within the universe in which we exist, we will first look to isolate and analyze

the phenomenon of language and consciousness in such a context. After more fully defining language as an intentional "triadic"

event, we then will consider the disparate relationship between human experience and that of other organisms. In particular, we

will be interested in identifying the unusual manner by which language forces us to confront the world.

Overall, then, some of the specific questions we will consider are the following: What is language? What is its relationship as a phenomenon among other phenomena? What exactly does it enable us as a species to do? How does it "orient" us to the universe? What kind of relationship does it establish between its users? And where does language elude science even as the latter is dependent upon it?

As we begin our inquiry into Percy's thoughts on language, to be direct about the matter of "language" is about all we can do in any desire to explain it (for reasons soon to be made apparent), so we must begin with a direct question and ask, What is language? But of course, the reader will recognize that such a question is not easily answerable, for implicit within the question is language itself, which is no small problem! [1]

As Percy explains, the problem is one of looking "at" rather than "through" language, for it is language that allows us the ability to conceive of "language." For instance, in one of his many essays on the subject, Percy the philosopher offers that "trying to penetrate the act of naming [i.e. language] is like trying to see a mirror while standing in front of it. Since symbolization is the very condition of our knowing anything, trying to get hold of it is like trying to get hold of the means by which we get hold of everything else." [2]

We are from the start, then, caught within a circle of sorts, trying to objectify the means by which we conceive, to make external that which is inviolably internal. In fact, you might say that we are trying to come to terms with that which gives us our terms! A strange predicament indeed. Yet this is merely the first problematic of many which we will consider throughout the following exploration of language and its relationship to consciousness. Let us, however, temporarily suspend this first complexity for the moment by situating language in another context, by making an attempt to understand it via comparison.

Let us modify our question, then, to the following: What is language as a phenomenon compared to other phenomena in the universe? (No doubt, this context is the most encompassing one we readily can admit). This particular question, indeed, is precisely what Percy has meditated upon at great length in his considerations of language and mankind. And perhaps most interesting of all is that his perspective, moreover--as will be demonstrated--is one that is empirical (scientific), even as it is philosophical.

By attempting to consider language from an extra-linguistic vantage point--to whatever extent we actually are able to do this--as a singular phenomenon alongside other phenomena, we can thus attempt to sidestep our immersion in language. With any good fortune, we then will be able to gain a better view upon mankind's capacity to manipulate language. So as our first task, let us, therefore, consider the more general phenomena of the universe before returning to language--that is, establish the context in which to discuss it.

Despite all its manifold complexity and vastness, the universe and all known phenomena within it, Percy tells us, may be accurately described according to one term: dyadic["dy-" fr. Gk dyo, meaning "pair" or "two"]. This is to say more specifically that all the numerous physical systems of the universe can be comprehended as events in which one given force or entity is acted upon by another in a cause-and-effect relationship as represented by the following equation: A --> B, or vice versa. For example, such typical spacetime events as particle combinations, energy exchanges, gravity attractions, field forces, etc., all may be understood as dyadic, cause-and-effect occurrences. [3] Whether we are talking about such individual events, then, as white dwarfs, red giants, or supernovas, or in turn the larger galactic systems of which these individual spacetime events are but parts, each system is comprised of "dyadic" interactions. Even with the multiplication of all these various phenomena together as they embody a given (larger) system, they nevertheless can all be comprehended as dyadic cause-and-effect relationships, for all such events may be understood functionally as one variable (A) as influenced by or made a product of another (B) and so on. See diagrams 1 and 2.

Variable A --> Variable B --> Variable C

which in turn creates

Event A --> Event B --> and so on

Diagram 1 illustrates the manner in which smaller scale dyadic sequences combine to form larger spacetime events, systems, etc.

Diagram 2 illustrates how even a system as inconceivably vast as the universe itself can be understood as a dyadic system. Image source: Lost in the Cosmos (Percy, 87).

Here on the Earth, this understanding about the dyadicity of the universe is likewise true for organisms and the biology of which they are composed. For example, whether an internal biological exchange involving chemical reactions, cell transactions or any other bodily processes, or whether an exchange that is external (such as feeding, breathing, or reproducing) each biological activity/exchange is dyadic in nature. For instance, we might note that reproduction for all higher organisms involves the interaction of two differentially-sexed members of a given species. The combination of the sperm of the male with the ovum of the female forms a new organism, whose own body will in turn develop in accord to the dyadic systems model. Whether directed at internal homeostasis, then, or at satisfying environmental needs, all biological interactions of the living biological organism are dyadic. See diagram 3.

Diagram 3 illustrates the interactions of an organism within itself (A-B), between itself and other members of its species (C-D), and with the environment (E-F).

Thus, in sum, the entire cosmos (both the inorganic and the organic) can be explained as one huge dyadic system comprised of smaller dyadic systems, all of which operate according to the cause-effect formula--that is, with one exception: SYMBOLIC LANGUAGE. Let us consider how this is so by returning to our reformulated question; that is, What is language as a phenomenon compared to other phenomena in the universe?

In answer to our question, Percy offers that human language, unlike the known cosmos, is not reduceable to the level of a dyadic relationship and instead must be understood as a triadic phenomenon standing in marked contrast to the context in which it is found ["tri-" fr. Gk tri-, meaning "three"]. In particular, this is true because human language involves the manipulation of "signs," another term we may use for symbols.

To explain in more detail: "triadic" is Percy's term for describing the unparalleled spacetime event that occurs between the three-part relationship of the "sign-using self," the "sign," and the "object/referent" of that sign--all of which together comprise the act of "symbolization."[4]

For instance, we might take the example of the sign "book." The four letters which comprise this sign signify to the willing reader or hearer the object which is known by that sign, namely a hand-held, square object that binds together multiple pages inscribed with text. Thus as "sign-users," we each agree that the sign "book" stands for the "object" known by that name. This pairing may be termed as a symbol-meaning relationship. See diagram 4.

Diagram 4 illustrates the three-part relationship between the sign-user, sign, and its object/referent. The association between the sign (or symbol) and its referent may be understood as a symbol-meaning relationship that is "imputed," as defined below.In regard to our example of "book" above, we might further note also that the text of a book is itself comprised of chains of signs (in the form of sentences) that signify meaning to the reader, just as for instance this sentence is comprised of multiple signs that you are reading now. In fact, though it is not readily perceptible, with some thought the reader will observe that human existence is permeated through and through with signs (just as in a book), for whenever and wherever one looks, even as one looks, he or she is using language to make sense of "what" is being seen. One might even go so far as to say that we are virtually bombarded by signs, sometimes more than we care for.

For example, certainly, a prime benefit of returning home at the end of a day for all of us is that, in such a closed environment, we have greater control over the amount and kinds of signs that enter; for instance, we choose when and whether or not to answer the phone, to watch television, to read, or to "log-on," etc. Indeed, as for this latter, it may be that the Internet itself is the greatest and most densely concentrated battery of signs that humanity has ever been exposed to for both the quantity of information available and the rapidity by which it may be had! Who among us Internet users does not know the effects of what might be called the "brain-data oversaturation effect" from our having spent too many hours focused solely on the screen of our computer. And certainly, this writer himself downloads far more text than he will ever have a chance to skim, let alone read!

Be these things as they may, let us return to the thought that our main concern now is to recognize that all these signs (however they enter our minds and our homes) may be understood according to the triadic model we have here initially proposed. (In the next section we will be examining the mechanics of this model and the symbol-meaning relationship more closely.)

Thus, to conclude, I wish directly to assert what has been identified about symbolic language: namely that, as a triadic occurrence in a dyadic universe, the "language event" is a wholly unique, unprecedented phenomenon! Moreover, as far as we know, there is no other equivalent coalescence of elements within the universe that in any close degree approximates mankind's singular fascination and obsession with language. As Percy describes us, we are nothing less than "symbol-mongering" organisms. Indeed, evidence that language is such a significant feature of our existence as a species is clearly indicated when we note that estimates place the number of distinct human languages in excess of 4000.[5]

In addition, as a final example affirming the qualitative uniqueness of language as a phenomenon, let us note that is only through the "triad" that we are able to conceive of the "dyad." For as we have already noted in the examples of books (and the Internet), all recorded knowledge is indebted to the symbolic triangle. This capacity for manipulation of a triadic system is what Percy calls the DELTA FACTOR, a term he uses to signify mankind's unmatched level of relationship to and interaction with the cosmos. [In Greek the letter delta is represented as a triangle].[6]

Thus, as a first insight into

consciousness, we can understand that is it woven through and through with

triadic symbolization in the form of signs, as symbolization allows us to

assign names to the phenomena of the natural world and oneself. (How

successful we fully do either, is an issue we will not presently engage). Let

us now take a closer look at the nature of the symbol-meaning relationship at

the heart of the "triad" and the "delta factor." From there, we will move on to

consider how language assists the human organism relative to other organisms.

Thus, as a first insight into

consciousness, we can understand that is it woven through and through with

triadic symbolization in the form of signs, as symbolization allows us to

assign names to the phenomena of the natural world and oneself. (How

successful we fully do either, is an issue we will not presently engage). Let

us now take a closer look at the nature of the symbol-meaning relationship at

the heart of the "triad" and the "delta factor." From there, we will move on to

consider how language assists the human organism relative to other organisms.

The sun may be understood as a dyadic phenomenon;

the sentence stating so may not.

Let us ask, What is the nature of the symbol-meaning relationship which leads the triadic langauge event to supersede the dyadic event? As we are about to see, the answer to this question will lead us directly to another unusual property at the core of consciousness.

The answer is that the symbol-meaning relationship established between the sign and its referent involves an act of intentionality by the sign-user. For instance, as described above, the sign "book" is selectively intended by the English-thinking mind as meaning, as standing in place of, the object it represents. Thus when we encounter a new word we do not know, we ask, "What do you mean (or intend) by that term?" Given the answer, we then can incorporate the term [or sign] into our larger pool of vocabulary.

The same principle holds true when we encounter a new phenomenon which we don't recognize as a part of our broader field of experience. For example, say you are a continental denizen of the late 19th century, and you are interested in identifying a new stylistic trend in the art world characterized by a "dissolved, blurred sense of form," a "subtle, yet pure use of color," and an "overall mood of sensual immediacy" as associated with the work of Monet, Renoir, and the like. Once revealed as the art school known as "Impressionism," you can readily identify with the trend and respond to it more fully, for it has then become a part of your "world" (more about this last term below).

So it is, then, that in any situation like the above we frequently long to have a name for a given unidentified phenomenon in order that it may be integrated into our larger system of conscious knowledge. Such, in fact, is the primary characteristic (and perhaps burden) of being a conscious, symbol-using being: we have an overwhelming need to structure our experience through the act of "naming." And naming is, as has just been suggested, inherently an act of intentionality in relationship to the phenomenon being named (i.e., the triadic event) and to the community in which the "name" is meaningful.

In Percy's words, "the act of consciousness is the intending of the object as being what it is for both of us under the auspices of the symbol [or sign].[7] Thereby does the given object or phenomenon become "focused" for us by the perceiving mind, ready for future use. For instance, to refer back to the example concerning "impressionism," the art viewer now has a completely new tool by which to identify tendencies in the art world as well as by which to communicate his or her own thoughts about that trend to others who share an (intentional) understanding of the term themselves.

It is of course pertinent to note here that, except in the case of onomatopoeia (e.g., spatter, slice, boom, etc.), there is no "real-world" relationship between the sign and its referent. (For this reason, the line between the two is dotted and described as "imputed" in Diagram 4 above). The association between the two is purely conventional, as for instance what is known by the sign "book" in English is known by the sign livre in French, libro in Spanish, etc. All symbolic language thus may be understood to operate by the tacit mechanism of intentionality, whether we are aware of it or not. In short, to identify a symbol-meaning relationship is to intend it.

Let us now, however, take one more step closer to the symbol-meaning relationship we have identified as an intentional, imputed bond, asking, What is the connector or mediator of this relation? The reply to this question will help focus our understanding of why we identify this bond as intentional, rather than as dyadic in the form of a more plain stimulus-response sequence (for example, a dog who, at his master's utterance "ball," goes to look for the round object).

The answer to our question is as simple as it is elegant, though in its simplicity, its powers should not be underestimated. The connector that makes the symbol-meaning relationship possible is the copula "is": the sign "book" in our respective minds is its referent. (We can't even avoid the copula in our answer!) That is to say, "book" stands for the object known by that name, which both you and I have agreed to accept as a meaningful relationship. But the four-letter sign "book" doesn't just point to the object it refers to: it names it in what must be seen as a denotative relationship, not one that is simply stimulatory.

For instance, we will all agree that words (signs) have both denotations and connotations, the latter being a deviation of meaning from the former's more direct one-to-one relationship with its referent. In fact, we might observe that the connotative value of language is of particular importance to poetry. The more imaginative and suggestive a poet's use of connotative language is (e.g. metaphor), the more complex will the poem's signification value be, the more "meaning" will the poem be said to have. However, such complex signification processes as are present in a poem, though of a higher degree, are in kind generically the same as what is present in the "naming act" (or the act of simple denotation) we have identified as so fundamental to human existence. And all is made possible by the mind's implicit manipulation of the "is" copula.

For this reason, therefore, words can be said to have "meaning" rather simply be described as a stimulus-response (dyadic) sequence. As Percy phrases it, "in its essence the making and the receiving of the naming act consist in a coupling, an apposition of two real entities, the uttered name and the object. It is this pairing which is unique and unprecedented" as an event, a pairing made possible solely by the human capacity to intend relationships via the copula "is." [8] Let's take one other example to illustrate the uniqueness of the symbol-meaning pairing as a triadic event involving an intended copula.

There is a qualitative difference between say, an individual's flight response to the sign-utterance "Fire!" when it is yelled out in a crowded theater, and the situation in which a father tells a child that this phenomenon before him of leaping light and scorching heat is "fire." The individual's response in the theater is essentially the same as the dog's response at the command "ball." There is need for little conscious thought for what to do at such a cue. Yet there is a world of difference for the scenario involving the child, for he comes to learn (through the intentional act) that this odd little sound means the dancing flame he is watching. For him, a new symbol-meaning bond has been forged to remain an enduring part of his mind's repertoire of symbols.

As an experiment in witness to the symbol-meaning transformation of the sign as it comes to "mean" its referent, as in the child's case with "fire," one needs only repeat steadily out loud a sign such as "apple" as many times as possible in as short a time as you can. Such an exercise will split the fused symbol-meaning relationship to expose the sign for the drab little vocable (or sound) it is. Try it. In a parallel fashion, we might note that the more use a term has in a given cultural population at any particular time, the more "watered-down" the term's meaning will become.

Thus, we may understand that signs, based in the copula "is," don't simply point to their referents, they in a certain sense are their referents as made possible by the intending, imputing mind. See Diagram 5.

Diagram 5 illustrates the intentional relationship between the sign and its referent which is an imputed association involving both denotation and connotation.

To conclude this section, let us affirm our second insight into the nature of consciousness, that it involves a property of intentionality as manifest in symbolic language. For thereby we enable ourselves to establish symbol-meaning relationships that can be manipulated in the abstract within discourse as signs. And what a wonderful quality this is, as it lies behind all representations of language: song, poetry, literature, mathematics, etc. The symbol-meaning relationship in essence cannot be escaped, coming at us in all directions, from both within and without! This is one of the prime reasons I have specified that language is the structure of consciousness as that vehicle which establishes relationship between signs and their referents. In Percy's words, "a being is affirmed as being what it is through its denotation by symbol...by laying something else alongside [it]: the symbol."[9] In short, to name is to affirm the existence of a being.[10]

We will be returning to discuss other dimensions of the symbol-meaning relationship later in the essay, but with the above explication of the way in which the triadic language event is formed, let us now turn our attention to a more pragmatic look at language.

Let us ask, What specifically does language enable the human organism to do? In simplest terms, language is a means of representation, the unique ability to translate experience into thought as embodied by symbols, or signs. In Percy's terms, though, what language specifically creates for the human organism is a "world" (or Welt), which forms the mind. This "world" stands in contrast to the "environment" (or Umwelt), the realm of our and other organisms' physical/biological existence. Let us explore these terms more fully, by asking, What is the central difference between the two?

A major difference between humans and other organisms is that the former exists simultaneously in the (triadic) realm of symbols even as we exist biologically. In contrast, the experiences of other organisms are limited to existence merely within the (dyadic) realm of biology alone. For example, while as symbolic creatures we might meditate upon what we might like to have for supper or where we might want to eat, the lion or tiger merely responds to his biological craving for food and goes in search of whatever meal he may happen upon or where habitually he has found food before. There is no symbolic deliberation on his part, merely behavioral response to the internal stimulus of his hunger. But let us push this difference further, asking, What are the results of existence within a Welt?

The human possession of a Welt (or world) has radical implications, for our experience is as a result generically different from the experience of all other organisms. They can be described as merely existing in an "environment" (Umwelt), with little or no recognition of this "existing," while we are inescapably aware of our lives and their mortal quality. Indeed, the precise issue is one of re-cognition, of the ability to transcend mere biological existence and enter into the realm of the "ontological" via the symbol. The term ontology denotes here a state of being wherein the existing entity has the capacity for conscious awareness of its own existence, that is, recognition of its being. Of course, hand in hand with a recognition of the full limits of one's being requires an awareness of death, of non-being. Perhaps this is why victims of natural catastrophes often proclaim themselves to have a renewed appreciation for their lives, because they have directly encountered their ontological state by facing a near-death experience. We might say they thereby became intent upon the sign "life," particularly as its definition applies to themselves. An intense meditation upon "death," inaugurated through suffering, cannot help but better define "life."

Thus, we learn next that another property of consciousness is the awareness of one's awareness, the conscious knowledge that "I exist." In a word, this may be captured via the term ontology. (This term should not be confused with that of "ontogeny," which means the course of development of an individual organism). Though on some level we might say that all living things have a degree of consciousness-for instance, a plant responding to the sun might loosely be called a kind of "consciousness" of the sun-it is important that we recognize such as dyadic and hence qualitatively the lesser in contrast to the ontology of triadic consciousness. The same holds true for any organism's biological awareness between what is inside and outside as it makes its way through and responds to its environment. In Percy's terms, then, the difference between symbol-using organisms and other organisms is that the former "are no longer oriented solely pragmatically toward their environment but ontologically as its co-knowers and co-celebrants."[11] The symbolic world is ontological by definition.

For example, we may say that humans are ontological creatures, navigating experience via symbols, whereas birds are not, even though they interact with other birds via calls or signals. We asks questions about meaning; they do not. We make plans about and anticipate the future; they do not. Let us consider, though, another example to illustrate further the nature of the leap into ontology, into the realm of "meaning."

Percy states in one essay that the "greatest difference between the environment (Umwelt) of a sign[al]-using organism and the world (Welt) of the speaking organism is that there are gaps in the former but none in the latter. The nonspeaking organism only notices what is relevant biologically; the speaking organism disposes of the entire horizon symbolically."[12]

To put this in other words, the "gaps" in the horizon of the speaking organism (i.e. humans) are identified by the symbol/sign "gaps," or the sign "unknown," and these terms serve to make the entire field of mental vision complete. What is not known or perceived thus simply falls under the simulacrum of the sign "unknown," just, for instance, as the reader's knowledge of what is to come in the following pages of this book (assuming this is his or her first reading) would fall under the auspices of the same sign. The material ahead is "unknown" to the new reader. The author's challenge, of course, is to make this horizon as appealing as possible, so as to entice the reader along. Let us hope no quagmires lie beyond our present trail, for all writing is discovery for both reader and writer alike!

Future hazards be where they may, at our present step, let us ask another question: What, then, can we understand about the relationship between the "world" that is experienced as consciousness and the "environment" of the physical organism who accesses it via symbolic language? The point is simple, yet nonetheless profound: the mind has the ability to encompass or subsume the "environment" within itself. In other words, the (triadic) Welt encircles the (dyadic) Umwelt even though it is within the Umwelt that the Welt finds itself to be, just as the mind resides in the body. Such a domain is worth remarking, in more ways than one.

To this unusual state of affairs, we might add, of course, that the "world" of the human mind also might be said to have an "environment" of its own, that is, the field of mental experience that exists only within the realm of the abstract, the realm of human cognition. Thus not only does the Welt create a new "space" or realm within the universe, it also can envelop the "space" of the universe within itself! Indeed, this realization leads us to a renewed appreciation for the famous statement made by the grandfather of modern American poetry who proclaimed himself: "Walt Whitman, a cosmos...."[13]

Despite this unusual situation wherein one is subsumed by the other, let us leave this section, nevertheless, with the firm distinction in mind that the Welt is not the Umwelt. This should be clearly evident in that it is a given that any particular "sign" is intended to designate a "referent" that is not itself, just as for instance, the sign "book," which we considered earlier, is not the object that goes by that name, merely the name for it.

In sum, then, the "world" or Welt of the human mind is that space alone unique to the human species wherein understanding and consciousness are experienced, both being segmented by and composed of symbolic language. In contrast to other organisms, at its most fundamental level the language of the Welt thus gives us the ability to re-present our (biological) experience in the "environment" or Umwelt and to re-create it in our minds, alongside a host of other ontological issues concerning the need for meaning.

As we leave this section, let us therefore acknowledge a third important property of consciousness we have realized, the immersion in ontology, which is a human characteristic of no small significance. But the consequences of language do not stop here. Let us see how it inherently creates community.[14]

Let us ask, next, What is the significance of the triadic Welt as it relates beyond the individual? The answer to this particular question may again seem elementary, but as before, we hope the reader will recognize the striking nature of what, as Emerson says, may seem "common." The symbolically organized "world" allows for the possibility of states of "intersubjectivity"-that is, states of shared understanding-to occur between human organisms. Language is thus a bridge between the respective, individual vantage points upon the Welt. Let us have a closer look at this phenomenon.

Percy offers a fundamental definition of intersubjectivity as "that meeting of minds by which two selves take each other's meaning with reference to the same object beheld in common."[15] For instance, the author has just above alluded to a thought of Emerson, which has been given as a prefatory quote for this essay. From having considered this allusion, the reader has come to share an idea in common with the author of this book concerning two "objects," namely the personage of the 19th century poet and naturalist Ralph W. Emerson, and one of his particular thoughts. In this way, therefore, have we come to have an intersubjective "meeting of minds." Indeed, we might even note that this meeting transcends time-even as much as a over a century in terms of Emerson's part.

This might seem fairly self-evident, but indeed, we must note in a similar fashion that intersubjectivity is the foundational cornerstone of all human knowledge as is enabled by the triadic symbol-meaning relationship we have identified and discussed above. In other words, the condition of intersubjective potential presupposes all human communication. In fact, we ourselves, the reader and the writer, have been engaged in an intersubjective state ever since the former first picked up this book! We are at this very moment in a state of intersubjectivity, though we may be miles apart and have never met. Communication via symbolic language, in this light, must be recognized for the extraordinary event that it is, being wholly limited neither to time or to space! Truly, this is an unprecedented phenomenon for the universe, where all is measured according to relationships in both time and space. Let us, however, now look at the nature of this event more closely by considering a further description of intersubjectivity.

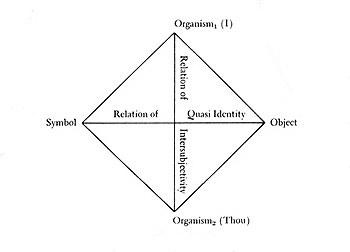

In one essay, Percy offers that intersubjectivity is describable as a "noncausal bond" forming a "tetradic relationship" of "Symbol" (or sign), "Object," "Organism1" (I), and Organism2 (Thou). See diagram 6.

Diagram 6 A representation of the "tetradic" nature of the intersubjective event between two organisms. Source: MB, 259.

Here, we might note that the triadic sign-meaning relationship has been realigned into a "tetrad" in the broader context of intersubjectivity. Two other points are significant about this diagram too.

First, the reader will note that there is only a relation of quasi-identity, that is of partial degree, between the "symbol" and the "object" to which it refers. This relationship is, as discussed above with the triad, one that is intended by the agreed meaning that the speaker and the hearer have attributed for a given symbol (or sign). For example, both the reader and writer agree that the sign "Emerson" refers to the 19th century writer who went by that name. This is a relation of quasi-identity. The word "Emerson" is not the man, who himself has long been since buried, ( but not his thoughts). This relation of quasi-identity follows thinking we have already outlined when we discussed the intentional identity of the sign above as arbitrary in nature.

Second, this tetradic bond is one that is noncausal because the tetradic event, unlike the dyadic event, is not brought about by one physical entity acting upon another to cause a certain outcome. Rather, the respective members of the given intersubjective pair both (triadically) intend the encounter through a conscious willingness which alone makes the exchange possible. Moreover, such an interchange can only occur within the realm of consciousness, the Welt. In Percy's terms, "a new and indefeasible relation has come into being between the two organisms in virtue of which they are related not merely as one organism responding to another but as a namer and hearer, an I and a Thou," as made possible by the co-intentional symbol-meaning relationship.[16] The intentional component of consciousness is again the key, the unique phenomenon we are attempting to be intent upon.

Given the understanding, then, that intersubjectivity is an intentional, non-causal event between two individuals, let us now ask, What can we understand about language itself? The answer, of course, is that language, besides being the vehicle of intersubjectivity, is intersubjective in nature in an of itself. As Percy would say, "symbolization is of its very essence an intersubjectivity...[and] presupposes a triad of existents: I, the object, you."[17] Put in other words, inherent in the "naming act" of language is the "hearing act," the I and the Thou both. To utter a word presupposes a listener, even if it is merely oneself.

Thus, for instance, the fact that Robinson Crusoe writes a diary that he is uncertain anyone will ever read does not in the least detract from the "communal" event that it is; that he writes, implies a reader. Indeed, we might say that above all, humans wish to have understanding as we communally stumble along the symbolic horizon of the Welt-wishing both to be understood and to understand. These both ultimately have their footings in intersubjectivity. We might also note that intersubjectivity is the ground making possible all incidences of empathy and identification, if not compassion too, during those times when "community" breaks down.

Another way to understand the simultaneity of the naming act and the hearing act is through the terminology of French philosopher Gabriel Marcel, whom Percy reflects upon at numerous points. In one instance, he cites Marcel referring to to the communal nature of language as an "intersubjective nexus." Simply put, this is to say that our relationship with others through language is implicitly a "metaphysic of we are as opposed to a metaphysic of I think."4 I think only because we think together as made possible by the language we both share. Moreover, to Marcel this "nexus" is what lies as the "mysterious root of language," which can only be "acknowledged," not "asserted." Put in other words, one participates in language, even to the extent that language subsumes the individual automatically into the community who uses that language.

For now, though, let us leave this section firmly intent upon awareness of the extraordinary nature of intersubjectivity as a non-causal, tetradic phenomenon, as well as with recognition for a forth property about consciousness we have discovered-the "communal" nature of knowing. For consciousness and intersubjectivity are inextricably inter-related and intertwined, their binding together beyond separation. As Percy would say, "I am not only conscious of something: I am conscious of it as being what it is for you and me."[18] Again, these are thoughts we easily lose touch with because we are so immersed in language, because it is so "everyday" (to use a term Percy was fond of) and commonplace to us. The complex wonder of language, however, doesn't stop with intersubjectivity.[19]

We have commented upon the triadic, ontological nature of the Welt and the noncausal, co-intentional nature of the intersubjective nexus. Let us now consider some further properties of language from this basis, while expanding on what we have considered before about the unique nature of the symbol-meaning relation. First, for the moment, let us take as a given that symbolic language involves the communication of "meaning," as for instance you may be wondering to yourself this very moment, "what does all this mean?"

Let us attempt a partial answer to this question with the following assertion: Understood as the very capacity to represent "meaning" and share it intersubjectively, human symbolization must be understood to be nothing less than a metaphysical event, as the means by which assertory exchange is created and made possible. To help clarify the meaning of our assertion, we need to consider the language event more closely, noting that it involves both a physical and a mental component whether we are talking about a sign that is visual (this or any other text) or oral-aural (a radio announcer). We will all readily agree that both situations involve easily recognized physical components: chains of black scribblings upon the page or sounds emanating from the radio speaker. These are clearly physical and are readily measurable or objectified. (For instance, one could readily study the underlying swssyntax, morphology, or phonology of our use of language for the former, or analyze the frequency, pitch, loudness, etc. of the latter).

On the other hand, however, what is not so clear is what these physical signs induce within the reader/hearer: the apprehension of meaning which in and of itself is not physical. For instance, above we referred to the 19th-century poet and naturalist known by the sign "Emerson." The relationship between this simple seven-letter vocative and the concept it refers to (i.e. the man known by that name) is one of imputed meaning, as we have observed. Therefore, since the symbol-meaning relationship is the product of an intentional bond, it follows that we can't "measure"-which presupposes a condition of physicality-intended concepts or ideas. We may be able to measure their effectiveness once they are implemented in a given project, but we can nowhere isolate a given concept and place it under a microscope! Moreover, this understanding holds true for all assertions, even the assertion that the preceding statement isn't true.

Awareness of the non-material condition of meaning has particular relevance as per the behaviorist model of language, which we briefly considered before by distinguishing between two instances involving the sign "fire." Let us look at this model in the interest of further demonstrating the position we are presenting.

Behaviorism holds that all organismic behavior can be defined according to the stimulus-response (S-R) learning model. In other words, behavior is understood to be the product of conditioning reinforcers, either positive or negative, as found in a given organism's environment. As an example, we might recall the manner in which Pavlov's dogs were conditioned to respond with salivation at the sound of a bell that had initially been paired with their feeding. To the behaviorist, then, the behavior of all higher organisms, human and non-human alike, can be explained according to the conditioning they have received.

Thus intent upon behavior as a functionally analyzable event, behaviorism is one of the strictest embodiments of scientific empiricism, and as found in its particular case, this tendency is manifest as a deemphasis on any motivational factors coming from within in the form of mental events (for example, behaviorists are generally antipathetic toward the Freudian psychodynamic model). For this reason the discipline is notorious for its narrowed treatment, if not dismissal of consciousness when studying humans. If any mental experiences at all are granted, they are held merely to be identical with neurophysiological processes. Anything else disqualifies the precepts of the model.

One famous statement by behaviorist founder John B. Watson demonstrates the general lack of importance he, as initiator of the paradigm, attributed to internal factors. Said Watson, "give me a dozen healthy infants, well-formed, and my own specified world to bring them up in and I'll guarantee to take any one at random and train him to become any type of specialist I might select-doctor, lawyer, artist, merchant, chief, and yes, even beggerman and thief, regardless of his talents, penchants, tendencies, abilities, vocations and race of his ancestors."[20]

Whatever truth value Watson's claim has (his proposal would be very interesting indeed were he to include "psychoanalyst" on his list!), his general perspective is based in the stimulus-response model we have identified, with its environmental emphasis. A similar approach, likewise, typifies behaviorist understanding of language as a dyadic S-R relationship. It is against this position that many of Percy's criticisms are directed in his essays.

For example, Percy suggests at one point, "it may well turn out that the [behavioral] semioticist has good reason to ignore the symbol relation in view of his dictum that sign analysis replaces metaphysics, since an impartial analysis of symbolization can only bring one face to face with the very thing which the [behavioral] semioticist has been at all pains to avoid-a metaphysical issue."[21] In emphasizing what is concretely measurable only, the behaviorist model overlooks the intentional bond, among other things, even though, of course, such is implicit within the behaviorist's own behavior.

Through such a critique, Percy is not advocating the abandonment of scientific "impartiality," as indeed, Percy's own model is quite scientifis. Rather does he wish to point out the deficiencies of a model which does not do full justice to the complexity of the language event, if not also that of mankind. For any given scientific model cannot be said to be a complete picture if it cannot explain all relevant phenomena without discounting or overlooking some in favor of others, especially when we are dealing with such a complex event as consciousness itself.

In the above example, we have thus sought to distinguish between language as a physico-causal event or sequence that is measurable (e.g., in the case of the radio announcer: sign utterance-> sound waves-> sensory reception by the hearer-> afferent nerve impulse-> cortical stimulation, etc.) and language as a "radical," "ontological" mode of being or "orientation" concerned with the expression and assimilation of "meaning" (i.e. intersubjective conceptual understanding), which is not quantifiable. To be sure, let us make this distinction between the measurable and the immeasurable further distinct, with a quick look at one more illustration.

Consider the scripts in diagram 7--none of which will probably be familiar to the average reader--while recognizing that each is laden with meaning to the writer and community who use them. Yet for us, their manner and style seem so radically unusual that to think that such marks suggest meaning is beyond one's comprehension! Literally. (If one is a scholar of ancient scripts, we suggest that he or she focus upon those languages that are not known).

It is, of course, equally interesting to think that our own English script would likewise appear as unusual to many of the writers of these scripts. With any good fortune, this little experiment in cross-cultural language analysis has helped the reader see more directly the radical divergence between the physical and metaphysical properties of the symbol-meaning relationship. (This is merely an extension of our earlier experiment with "apple"). We, of course, have already noted the way in which Emerson's ideas have transcended time and place, even though the physical component of text is required along with the biology of one's brain. Likewise, we have considered the metaphysics of the intersubjective nexus, so hopefully between these three, the uniqueness of the triadic language event is becoming ever more obvious to the reader.

Let us now begin considering the fuller implications of what we have discovered about the symbol meaning-relation as a whole.

Given the peculiar properties of "meaning" we have considered, interesting implications follow along two lines: both in terms of what we can understand about mankind in itself and in terms of the products of its efforts. Let us save discussion of the former for the concluding section of this essay and turn first to the products of our desire to understand, particularly as per science. Indeed, what we are about to consider might be suggested to be the greatest kept "secret" about science, one that is so secret that even most scientists are unaware of it themselves! Let us begin by offering a general definition of science and its methods.

As a process, science is initiated by the desire to understand an identified problem in the natural world as concerns a given phenomenon. One then begins to study this phenomenon by limiting as many variables associated with it as possible, followed by the gathering of data about it. Through systematic observation intent upon objectivity and impartiality (i.e. employment of the "scientific method"), the scientist then can inductively formulate "hypotheses," or educated guesses, in explanation of the phenomenon that is not understood. If one's hypothesis about an event proves correct, and can be verified by repeated "experimentation" and testing, then this hypothesis can be accepted as accurate and generalizable to other scenarios involving that given phenomenon. The hypothesis at this point is then elevated to the the level of a "principle" until it is disproven or modified by further findings.

If the weight of evidence supporting the principle, however, is so convincing that its findings cannot be disputed, and they have stood the test of time in light of repeated experimentation by other scientists, the explanation for the phenomenon then may achieve the status of "theory," or of "law." Such a status allows the explanation to be accepted as a general frame of reference for all further inquiry into any situation involving that same phenomenon or set of phenomena. Newton's First Law of Gravity is one such example of a hypothesis now writ large as Law. The combination of multiple laws may enable the scientist to develop larger models as pertain to the prediction of behavior within ever larger systems involving more and more complex phenomena. In physicist John Barrow's words, "the goal of science is to make sense of the diversity of Nature...[through] the transformation of lists of observational data into abbreviated form by the recognition of patterns," all with the goal in mind of "algorithmic compression."[22]

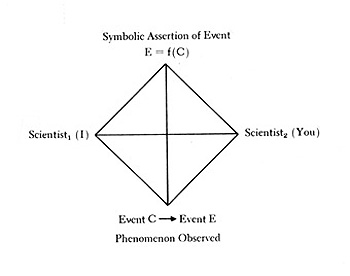

Thus, for instance, we have the General Theory of Relativity predicting behavior about the large-scale structure of the universe, and Quantum Mechanics Theory offering predictions about phenomena on extremely small scales at the sub-atomic level. Science thus involves the analysis and computation of data in the interest of attaining an ever more broad understanding of the phenomena of the natural world. From this data, theories and models then can be derived. As a model itself, the scientific method can be outlined as seen in diagram 8.

Problem Identification-->Systematic Observation-->Hypothesis-->Experimentation--> Generalization

Diagram 8 illustrates the general stages of the scientific method. The process toward scientific knowledge is one that is recursive, rather than linear.

Inherent to all scientific methodology on a mechanical level is the interest in how one event/variable/phenomenon is a "function" of, or is "caused" by, another event/variable/phenomenon. (This is our basic dyadic model of A->B discussed above). Moreover, the cause and effect relationship between variables must be measurable and limitable to a specific point/context both temporally and spatially in order for relationships to be clear and predictable. Scientific models, above all else, wish to offer accurate predictions about what will happen for a given scenario. Let's take an example by returning to Newton.

Newton derived his First Law of Gravity by examining events about him (the falling of an apple), followed by the formulation of the idea of "gravity" to explain the phenomenon of physical objects falling to the ground. In other words, the falling object (apple) is a function of gravity as is present on the Earth at any given moment or place. This, he reasoned, must also explain why the moon orbits the Earth, and he generalized his ideas into a larger model in explanation of the behavior of the heavens. This law among others thus served to unify his ideas in Newton's Principia (1687), arguably one of the most important scientific works ever published.

Thus, as this example demonstrates, scientific analysis into natural behavior may be represented by the following formula: E=f(C), where "E" represents a given event, "C" is the cause of it, and "f" represents their relationship, namely that "E" is a function of "C." In a nutshell, this is one the first major principles of all scientific inquiry. The reader should immediately recognize this as a concern with the dyad.

E=f (C)

Diagram 9 This formula stands behind all scientific knowledge wherein a given Event (E) is identified to be a function (f) of some Cause (C).

This brief definition of scientific method in mind, both its overall procedure, as well as its mechanics, let us now ask what might prove to be a very important question. Have there been any important variables or phenomena left out? That is, in the attempt to systematically measure and interpret the dyadic phenomena of the world, has something been overlooked? Percy argues that, yes, indeed something very important has been left unconsidered. Let's see how.

It is a given that scientists study the phenomena of the natural world, which in some cases even includes the study of our own species. But lest we forget that mankind is a complex "phenomenon" in its own right, we need also to ask questions on several different levels at the same time. Particularly, we need, as Percy advocates, to seek to understand human culture in all its many manifestations, including science itself.

This leads us, then, to another question, Who is studying the scientists studying natural events-those both human and non-human-as they attempt to expand the boundaries of scientific knowledge? No other species, of course, pursues such radical behavior, but can we simply disregard such questioning as an extraneous variable? Percy believes not, and as a good "scientist" himself, he makes it his responsibility to reflect upon the curious nature of this scenario.[23]

What are the results? The reader shouldn't be surprised that the issue again pertains to language, and if he or she hasn't yet formulated the answer to the "secret" of science, let us state it directly now: assertions of meaning are the fundamental, prerequisite given of all scientific activity, and yet these assertions are not themselves subject to the criteria of empirical scientific methodology. To put it in Percy's words, the "functional method of the sciences cannot construe the assertory act of language."[24]

All this is simply to repeat again the understanding we have already discovered, namely that the phenomenon of asserted "meaning" is not subject to measurement as a "causal space-time event," even though it is accepted as being as real as those natural phenomena that can be construed functionally. Thus, for example, we can state that a scientist's asserted conclusions or ideas concerning a body of data are not functionally measurable whereas, in contrast, the behavior of the scientist asserting his or her conclusions is fully definable according to scientific precepts. The latter is a physico-causal event, whereas the former is not given the noncausal, immaterial nature of "meaning. " Yet is it any less of a "natural" phenomenon? See diagram 10 below.

What are some of the immediate implications of this understanding? For one, no matter what the proposed Superconductor Supercollider (SSC) will be able to tell us about the the fundamental sub-quarkian nature of matter and the early microseconds of the birth of the universe, when in operation its speeding protons will never be able to bombard or collide with an assertion, even with the fastest of particles racing around its track! Such simply can't be done, this even with the expectation that early tests scheduled for the beginning of the 21st century are to create levels of energy over 20X the level of power that has ever been achieved by scientists before.

Yet, of course, we know the assertory event to be as "real" as colliders themselves, for they are the fundamental upon which they are built. Indeed, the energy levels of assertions have been the driving force of other world events of immense power and scope-from everything to the development and rise of Greco-Roman civilization, to the re-vitalization of culture during the Renaissance, to the founding of Modern industrialization, all things to which modern science is indebted and without which it could not have risen. Thus, as scientists and others eagerly await the completion of the SSC, dare we not stand likewise in awe and remembrance of the immense power of the human mind in all its own complexity and unexplained nature?

It takes someone as gifted as Percy, however, to remind of the important limitation intrinsic to all scientific understanding: that for all its ability to grasp, peer into, and fathom the very depths of the universe and the human body, for all its beauty and elegance, the scientific method nonetheless cannot be used to explain itself! Nevertheless, what science by definition excludes from its boundaries, that is, nonempirical phenomena, inviolably ends up being bound within it.

Does this mean that science is not a useful, productive tool for shaping and understanding the world? No, by no means. The modern world is greatly indebted to scientific advances in more ways than can be counted. But it does suggest that science does not fully penetrate into the elaborate fabric of reality as it intends to encompass. Recognition of this fact may be especially significant at a time when scientific-technological values still reign supreme in cultural perception as being the only viable world-vision with anything of substance to communicate or contribute to humanity. (Of course, many ills have been a part of this contribution too, but we leave that issue to someone else). Our goal, here, like Percy's, is simply to challenge and to question hidden assumptions in the interest of furthering our awareness of ourselves, our cognizance of the human predicament. Thus, let us conclude this section on the mediation that, in light of the limitations we have above realized about science-that perhaps other modes of inquiry are necessary alongside it if mankind is in any way to address its yearning for "meaning," which is, after all, the very condition of science in the first place.[25]

Diagram 10 demonstrates the intersubjective relationship between scientists (left and right) as combines a symbolic assertion (top) in explanation of a given event that may be understood functionally. Though the symbolic assertion describes a cause-effect relationship, its own peculiar character in not understandable so.

Let us conclude our initial mediation on language and consciousness by considering just some of the implications of what we have discovered. Indeed, let us ask, What does all this mean?

This question very well, arguably, could be seen as the central question to the condition of humanness, to the "predicament" of consciousness, but there is no simple answer to it, not from science, not from philosophy, not from religion. We will, however, continue to reflect upon the nature of consciousness, meaning, and interpretation through the entirety of this book. For the time being, though, let us bring our journey to a point of greater synthesis in light of what we have covered so far, first by reviewing what we have learned about language, then consciousness, and then mankind.

To begin, we have learned that the language event is an illusive one because it is only through language that we can conceive of "language." By looking to a broader context, however, we more readily were able to isolate language as a triadic phenomenon, one that stands in marked contrast to all other known phenomena in the entire cosmos. Likewise, we noted that our existence as sign-users is interpenetrated through and through by signs, despite our lack of awareness for them. Following a discussion of the intentional bond-the imputed pairing between the sign and its referent-as lying behind the symbol-meaning relation of the triad, we considered the nature of the Welt, or the symbolic world formed in language. Intimately connected with this new "realm" in the universe, we learned, is the condition of ontology, having awareness for one's awareness even as one symbolically disposes of the entire horizon of the Umwelt, the biological realm.

Likewise, we then saw how the Welt allows for intersubjectivity to occur as a tetradic non-causal bond between two organisms. Moreover, we observed that language itself is intersubjective in nature in that implicit in the naming act is the hearing act. As such, we recognized that intersubjective potential is prerequisite for all knowledge. In turn, we then explored more fully the metaphysical nature of "meaning" as a phenomenon that is not wholly explicable in physico-causal terms. And finally we extended our mediation upon the unique properties of language into the world-frame of science, while observing the way in which the assertory event which lies at the heart of science is not itself subject to scientific methodology.

What in turn have we learned about the nature of consciousness? We have learned that consciousness is bound up with and wedded to symbolic language, as language mediates between the mind and the universe by allowing for the allocation of names to the phenomena of nature and oneself. Likewise, we discovered that consciousness involves intentionality, by which relationships between signs and referents are fused to create the symbol-meaning relationship behind symbolization. In turn, we then unearthed the ontological nature of consciousness as a mode concerned with the assimilation and exchange of intended meaning, as a unique orientation to the physical realm of being. Moreover, we noted that consciousness as we are defining it involves the knowledge that one "knows" he or she knows.

Likewise, we discerned the communal nature of consciousness as bred of the intersubjective nexus between ourselves and others via language, recognizing that one's own consciousness is inextricably tied in with the intersubjective tetradic bond, that is others' consciousness. Additionally, we observed that this nexus can only be acknowledged, not circumscribed. Moreover, and perhaps most importantly, we saw that "knowing" is a non-causal sequence that is not wholly limitable to the physical because "meaning" transcends the physico-causal. It cannot be measured simply as a functional state of dynamic energy exchange.

Where then does all this lead us in our initial attempt to apprehend consciousness? For one, we might note that to the extent that consciousness is intertwined with the above triadic relationship we have identified, it cannot alone be fully explained by a dyadically-inclined methodology, in other words, current scientific models. And since consciousness brings the human organism into a totally new relationship to the environment as a mode of being borne toward ontology and community-both of which are implicit in science-the phenomenon would seem to ask for approach from multiple perspectives. At the very least, however, we must acknowledge that we are so immersed in consciousness that we easily loose sight of its unusual properties, which we have above sought to bring into greater relief.

And finally, let us ask, What of mankind? What can we understand about its relationship to other species? Foremost, we have learned that because the triadic realm of the Welt is alone mankind's, a major distinction exists between human experience and that of all other known species. Moreover, this difference between humans as "namers" who perceive from the vantage point of symbolic language, and other organisms who merely exist in the Umwelt as signal-users, is one that is not merely quantitative but qualitative. For on the Earth only mankind is ontologically oriented to the universe.[26] Ontology, of course, is both a blessing and a curse, as on the one hand it allows our species to shape our environment more successfully where on the other hand it thrusts us into the uncertain straits of ever elusive "meaning."

Despite human uncertainty, there is one thing that is certain as concerns our present interests: in all its symbolic and syntactical complexity, human language, as the very fiber of consciousness and as the means by which we "process" the environment (Percy also, as we have seen, uses the term "celebrating" it), categorically places mankind in a different sphere in relationship to other organisms. For nothing less than a gulf exists between the responses of animals to stimuli in the environment and the assertory propositions of mankind, a gulf or chasm that is not bridgeable by biology alone.[27] As a result, any attempt to equate humans as simply a higher organism not qualitatively different from other organisms falls into an immediate antinomy at its very assertion, for only humans venture to make assertions. To conclude, once considered in a larger light as Percy presents, human consciousness and language must be recognized as the utterly distinctive means of "knowing" and "interpreting" that they are. Percy's direct challenge to us is that mankind seek to broaden its vision of itself relative to the "tradic language event." Before any minimal conceptualization of humans as "organisms" can be reached, he suggests, a more thorough consideration of language and consciousness must be pursued.

Abbreviation Key for Walker Percy Books in Footnotes:

MB = Message in the Bottle

LC = Lost in the Cosmos: The Last Self-Help Book

SS = Signposts in a Strangeland

TP = A Thief of Peirce

SE = Symbol and Existence: A Study in Meaning: Explorations of Human Nature

2"Naming and Being" (SS, 132). This essay is probably the best original introduction to Percy's ideas on language for the non-specialist.

3Our discussion of the "dyad "and the "triad" below find their source in "A Semiotic Primer of the Self" (86-127, LC).

4Percy alludes to the work of American logician and philosopher Charles Peirce (1839-1914), one of the fathers of semiology, for his original inspiration for "triadic theory." It is probably within Percy's essays, "Is a Theory of Man Possible?" and "The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault in the Modern Mind" in SS that he acknowledges Peirce most at length. (See Kaja Silverman's The Subject of Semiotics (1983), pp. 14-25 for a more extended, critical treatment of Peirce's ideas as a whole).

Other figures to whom Percy acknowledges debt include Ferdinand de Saussure, Hans Werner, Susanne Langer, and Martin Heidegger, alongside of Ernst Cassirer, Martin Buber, Gabriel Marcel, and Soren Kierkegaard. "Semiology" is the formal, scientific study of signs and their signification.

5David Crystal, editor of The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (1987), notes: "there is no agreed total for the number of languages spoken in the world today. Most reference books give a figure of 4000 to 5000, but estimates have varied from 3000 to 10,000" (284).

6Percy's essays in which discussion of triadic language is found include the following: "The Delta Factor," "Toward a Triadic Theory of Meaning," "The Symbolic Structure of Interpersonal Process," and "Semiotic and a Theory of Knowledge" from MB; "A Semiotic Primer of the Self" from LC; and "Is a Theory of Man Possible?" and "The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault in the Modern Mind" from SS.

As an aside we might note that there is a very real sense in which Percy's language theory, because of its larger cosmological context, envelops all other language and literary theories, including literature itself. Moreover, besides language's organization as a "triad" via the symbol-meaning relationship, it is also interesting to note other "triadic" dimensions of language. For example, as Richard Restak notes, human language takes the shape of three forms: speech, sign, and script. Likewise, Walter Ong in his work offers that communication has passed through three stages during the history of mankind: the oral-aural, the chirographic-typographic, and the electronic.

7"Symbol, Consciousness, Intersubjectivity" (MB, 274). This is one of Percy's more thoughtful technical essays.

8"Semiotic and a Theory of Knowledge" (MB, 261).

9"Semiotic and a Theory of Knowledge" (MB, 263).

10 I choose not represent post-structuralist thought in this statement, for what I hope is the obvious reason that language as an activity is necessary for the articulation of post-structuralism itself. I do, however, intend later to address post-structuralist criticisms of language in an essay I am writing on Percy's semiotics of "self" to appear in the WPProject at a future date.

11Symbol, Consciousness, Intersubjectivity" (MB, 272).

12"The Symbolic Structure of the Interpersonal Process" (MB, 203). As among many semioticians themselves-the field being multi-disciplinarian-and even within the longer course of Percy's career writings, there is and has been variability in the meaning of the term "sign" (as Percy himself notes). The author has chosen here in a quote from Percy's 1975 essay collection to modify Percy's statement to represent a change which he himself sanctions at a later date in his footnote to "A Semiotic Primer of the Self" (LC, 1983).

Here, Percy proposes to use the term "signal" to denote the dyadic communications of animals (e.g. the bird's instinctually-encoded response to the stimulus of its relative's warning call about a nearby danger, for instance, a cat). In contrast, he proposes to use "sign" solely to represent triadic human communication, which involves the expression of "meaning."

At this time, he also proposes to use the term "symbol" only sparingly, because it too connotes something other than the notion of "sign," as say, we have cultivated so far above in the main text. For instance, we speak of a flag as a "symbol" of a country. "Signs" on the other hand are readable and exist in a much more complex environment alongside of other signs, for example, as in the text before you. We will continue, however, to honor Percy's use of the term "symbol" in his quotes from his pre-1983 essays, where we would normally want to use the term "sign." This distinction is not as crucial as that between "signal" (non-triadic) and "sign/symbol" (both triadic). We will likewise continue to use Percy's term "symbolization," for both "symbols" and "signs" are forms or types of triadic symbolization.

Because the general reader, the author feels, would more readily identify with the term "symbol," we have used it initially to introduce him or her to the unique properties of language, before weaning him or her to the term "sign."

13See "Song of Myself," stanza 24 from Whitman's Leaves of Grass, one of his more self-celebratory anthems.

14Specific essays in which Percy mentions the Welt and Umwelt include: "The Symbolic Structure of Interpersonal Process," in MB; "A Semiotic Primer of the Self" in LC; and "Is a Theory of Man Possible?" and "The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault in the Modern Mind" in SS. The terms have their origin in Existential thought.

15"Symbol, Consciousness, and Intersubjectivity" (MB, 265).

16"Semiotic and a Theory of Knowledge" (MB, 257).

17"Symbol as Hermeneutic in Existentialism" (MB, 281).

18"Symbol, Consciousness, and Intersubjectivity" (MB, 271).

19"Symbol, Consciousness, and Intersubjectivity" (MB, 274).

20Essays in which Percy specifically treats intersubjectivity include: "The Symbolic Structure of Interpersonal Process," "Semiotic and a Theory of Knowledge," and "Symbol, Consciousness, and Intersubjectivity" in MB.

21Hergenhan, B.R. An Introduction to Theories of Personality (1984), p. 171.

22"Semiotic and a Theory of Knowledge" (MB, 246). The term "semioticist," like that of "language" above in footnote two, is one used variously within different disciplines. Here, I have modified the term to reflect Percy's stated referent in this essay.

23Theories of Everything: The Quest for Ultimate Explanation (1991), p. 10-11.

24In the last chapter of his Pulitzer prize winning book, Gödel, Escher, Bach (1979), Douglas Hofstadter speculates that, after the successful mirroring of the mind in Artificial Intelligence, "perhaps the next step after AI will be the self-application of science: science studying itself as an object" (699). We might offer Percy's findings as presented below as one, perhaps significant, part of the answer.

25"Culture: The Antinomy of the Scientific Method," (MB, 230). Within this essay does Percy most directly argue the main idea of this section.

26For other essays where Percy critiques and analyzes modern science, see the following essays "The Delta Factor," "The Loss of the Creature," "The Message in the Bottle," and "Culture: The Antinomy of the Scientific Method" from MB; and "Is a Theory of Man Possible?" and "The Fateful Rift: The San Andreas Fault in the Modern Mind" in SS. The latter two essays are probably the most thorough in their scope.

27Noam Chomsky, the renowned linguist who revolutionized modern linguistics with his Theory of Generative Grammar agrees: "Any objective scientist must be struck by the qualitative differences between human beings and other organisms, as much as by the difference between insects and vertebrates" (Language and Responsibility [1979], 95). It is in his essay "A Theory of Language" [MB] where Percy most directly addresses the ideas of Chomsky.

See also linguist Derek Bickerton's statement: "the trouble [of the Continuity Paradox] is that the differences between language and the most sophisticated systems of animal communication that we are so far aware of are qualitative rather than quantitative" (Language and Species [1990], 8). As explained in Bickerton's first chapter, the Continuity Paradox reflects the idea that there are no identifiable existing animal language systems that could serve as an intermediary between human and animal communication in the former's evolution.

28Cf. Percy's assertion: "no space-time event, however intricate, no chemical or collodial interaction, no configuration of field forces, can issue in an assertory event [e.g. E=MC2]. As Cassirer put it, there is a gap [or gulf] between the responses of animals and the propositions of men which no amount of biological theorizing can bridge" (MB, 219). Cf. also, the ending of "The Mystery of Language" (MB, 158).

BOOKS BY WALKER PERCY (Language and Philosophy)

Percy, Walker. The Message in the Bottle: How Queer Man Is, How Queer Language Is, and What One Has to Do with the Other (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1975). Also, referred to as MB.

Percy, Walker. Lost in the Cosmos: The Last-Self Help Book (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1983). Also, LC.

Percy, Walker. Signposts in a Strange Land (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 1991). Also, SS.

Percy, Walker and Kenneth Laine Ketner; Samway, Patrick, ed. A Thief of Peirce: The Letters of Kenneth Laine Ketner and Walker Percy (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1995). Also, TP.

Percy, Walker. Symbol and Existence: A Study in Meaning: Explorations of Human Nature (Mercer University Press, 2019). Also, SE.

Bickerton, Derek. Language and Species (Chicago: University of Chicago, 1990).

Chomsky, Noam. Language and Responsibility, John Viertel, trans. (New York: Pantheon Books, 1979).

Crystal, David, ed. The Cambridge Encyclopedia of Language (Cambridge: University Press, 1987).

Emerson, Ralph Waldo. "Nature," Norton Anthology of American Literature, Vol. 1, 2nd ed., Nina Baym et al (New York: Norton, 1985).

Hergenhan, B. R. An Introduction to Theories of Personality, 2nd ed. (Englewood Cliffs: Prentice- Hall, 1984).

Hofstadter, Douglas. Gödel, Escher, Bach: An Eternal Golden Braid (New York: Vintage Books, 1979).

Lawson, Lewis A. and Victor A, Kramer. eds. Conversations with Walker Percy (Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, 1985).

Restak, Richard. The Mind (New York: Bantam, 1988).

Silverman, Kaja. The Subject of Semiotics (New York: Oxford University, 1983).

Whitman, Walt. Complete Poetry and Selected Prose, James E. Miller, ed. (Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1959).

Walker Percy's Semiotics section

An Annotated Bibliography of Walker Percy's Writings on Language

Walker Percy's Writings on Language (By Original Publication and Date)