With this, you actually have an AGC program that

does something, and does it both visibly and testably ... if not

very excitingly.

With this, you actually have an AGC program that

does something, and does it both visibly and testably ... if not

very excitingly.Actually, I lied in the title of this page and in item #7 of the list above. There's no profit, unless your own personal enjoyment and sense of accomplishment counts as profit. (Prove me wrong!) But the other topics, #1-5, are discussed further throughout the remainder of this page.

An important thing to know about "embedded programming", of which

AGC software is an example, is that there are two basic varieties

of embedded programming and embedded programmers:

The AGC is an odd case, because while it has very, very small

resources (tiny memory, terribly slow), it nevertheless has a

pretty capable operating system written but a bunch of smart

people. We will therefore cover both bare-metal programming

and operating-system-based programming. My advice would be

to start with the former until you're familiar with what you're

doing, and then graduate to the latter if it turns out you need to

do so.

Actually, the values in the list of input channels returned by inputsForAGx()

are something the Python language calls "tuples" or specifically,

3-tuples. Each 3-tuple has, as you may imagine, 3 parts:

The interpretations of the channel and value parts are probably obvious. The mask part indicates which bit positions of the value are valid. Only the bit positions of value for which the mask is 1 end up affecting the AGC's input channel, and the bit positions in the input channel corresponding to 0 in in the mask remain unchanged. This feature is needed in general because some input channels have bit-fields controlled by one peripheral device and other bit-fields controlled by other peripheral devices, and you don't want a peripheral device to change the wrong bits. For i/o channels you've defined yourself, of course, that probably isn't an issue, and the mask could always be 32677 (077777 octal).( channel, value, mask )

[ ( 0o45, 0o5, 0o00007), (0o46, 0o12345, 0o77777) ]Note that in Python 3, octal constants are prefixed by "0o".

As it happens, the sample peripheral program piPeripheral.py in our GitHub repository has been pepped up slightly from just a bare template. Additionally, it defines and processes several new i/o channels just to give examples of how to do so. This extra stuff is active only when the command-line switch --time=1 (or actually, --time=anything) is used, so you can easily eliminate it if you choose to build your own peripheral device starting from piPeripheral.py. Here's a list of these newly-assigned channels:

The input channels are actively generated by piPeripheral.py,

while the output channels merely have their contents printed

out. The AGC program processing the input channels (in which

the date and time is packed in a non-human-friendly way) might

use the output channels for reporting human-friendly unpacked date

& time data. Of course, the AGC program might choose to

do something else altogether or even nothing at all with these

extra channels.

And of course, the main idea behind providing the current time

and date in this way in the first place, is that it might serve as

the basis for using the AGC+DSKY as a clock widget on a computer

desktop. That's because we really mean the current

time, and we don't mean something like "time since powerup", which

is otherwise all that the AGC knows about on its own. This

idea of a clock app is continued in the next section.

SETLOC 4000But that's a bit of an over-simplification. The actual significance of address 04000 is that it's the start of an interrupt-vector table — i.e., of code which is instantly automatically executed whenever certain exceptional conditions occurs. For example, if the DSKY sends the AGC a keystroke, it instantly "vectors" to the code that's associated with that condition, and it's not something that your AGC program necessarily has to explicitly check for.

STARTUP # Do your own stuff from here on

SETLOC 4000Even here, we're still simplifying a bit, since what you'd find if you started filling in code after the label STARTUP is that your code might execute for a while and then just reset and start again at address 04000! What's up with that? Well, behind the scenes, the AGC hardware checks performs various checks to determine if the computer has somehow frozen up, and of course, yaAGC tries to perform whichever of those checks are appropriate as well. If it detects any of these conditions, it performs a jump to address 04000, just as if a power-up had occurred. That's one of the features that lends reliability to the device. This restart is known as a GOJAM. I'm not totally sure what all of the conditions that could trigger a GOJAM are, but LUMINARY Memo #225 contains a handy list of 8 of them. The ones that are relevant to software that you yourself write are these:

TCF STARTUP

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # T6RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # T5RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # T3RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # T4RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # KEYRUPT1

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # KEYRUPT2

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # UPRUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # DOWNRUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # RADAR RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # RUPT10

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

STARTUP # Do your own stuff from here on!

Taking all of that into consideration, here's a minimal framework

you might use to start building your bare-metal AGC program:

# Definitions of various registers.

ARUPT EQUALS 10

QRUPT EQUALS 12

TIME3 EQUALS 26

NEWJOB EQUALS 67 # Location checked by the Night Watchman.

SETLOC 4000 # The interrupt-vector table.

# Come here at power-up or GOJAM

INHINT # Disable interrupts for a moment.

# Set up the TIME3 interrupt, T3RUPT. TIME3 is a 15-bit

# register at address 026, which automatically increments every

# 10 ms, and a T3RUPT interrupt occurs when the timer

# overflows. Thus if it is initially loaded with 037774,

# and overflows when it hits 040000, then it will

# interrupt after 40 ms.

CA O37774

TS TIME3

TCF STARTUP # Go to your "real" code.

RESUME # T6RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # T5RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

DXCH ARUPT # T3RUPT

EXTEND # Back up A, L, and Q registers

QXCH QRUPT

TCF T3RUPT

RESUME # T4RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # KEYRUPT1

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # KEYRUPT2

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # UPRUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # DOWNRUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # RADAR RUPT

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

RESUME # RUPT10

NOOP

NOOP

NOOP

# The interrupt-service routine for the TIME3 interrupt every 40 ms.

T3RUPT CAF O37774 # Schedule another TIME3 interrupt in 40 ms.

TS TIME3

# Tickle NEWJOB to keep Night Watchman GOJAMs from happening.

# You normally would NOT do this kind of thing in an interrupt-service

# routine, because it would actually prevent you from detecting

# true misbehavior in the main program. If you're concerned about

# that, just comment out the next instruction and instead sprinkle

# your main code with "CS NEWJOB" instructions at strategic points.

CS NEWJOB

# If you want to build in your own behavior, do it right here!

# And resume the main program

DXCH ARUPT # Restore A, L, and Q, and exit the interrupt

EXTEND

QXCH QRUPT

RESUME

STARTUP RELINT # Reenable interrupts.# Do your own stuff here!

# If you're all done, a nice but complex infinite loop that

# won't trigger a TC TRAP GOJAM.

ALLDONE CS NEWJOB # Tickle the Night Watchman

TCF ALLDONE

# Define any constants that are needed.

O37774 OCT 37774

So here you have simple framework with a few empty places in

which to insert your own code. Not to mention a few

interrupt vectors (such as the DSKY keypad interrupts, KEYRUPT1

and KEYRUPT2) that right now do nothing, but which you could

imagine might be very helpful.

What might the functionality for reading DSKY keystrokes look

like? Note that info about the i/o

channels pertaining to the DSKY are on the developer page.

Perhaps

you'd use the KEYRUPT1 interrupt-service routine to read the input

channel containing the DSKY keycode, and then store that keycode

in a variable. Your main program loop might periodically

check that variable to see it it contains anything, and then might

output something to the DSKY so you'd know it had been

detected. For example, it might toggle the DSKY's COMP ACTY

lamp every time there was a new keycode detected.

# Here's what the allocation of the variable to hold the keycode might look like.

# Plus, a variable that tells if COMP ACTY is currently on or off.

SETLOC 68

KEYBUF ERASE # 040 when empty, 0-037 when holding a code

CASTATUS ERASE # 0 if COMP ACTY off, 2 if on.

.

.

.

# Here's what the KEYRUPT1 interrupt-vector table entry might look like.

DXCH ARUPT # KEYRUPT1

EXTEND # Back up A, L, and Q registers

QXCH QRUPT

TCF KEYRUPT1.

.

.

# Here's what the actual interrupt-service code might look like.

KEYRUPT1 EXTEND

READ 15 # Read the DSKY keycode input channel

MASK O37 # Get rid of all but lowest 5 bits.

TS KEYBUF # save the keycode for later.

DXCH ARUPT # Restore A, L, and Q, and exit the interrupt

EXTEND

QXCH QRUPT

RESUME.

.

.

# Here's what it might look like in the main code.

STARTUP RELINT

# Initialization

CA NOKEY # Clear the keypad buffer variable

TS KEYBUF # to initially hold an illegal keycode.

CA ZERO

TS CASTATUS

.

.

.

# Occasionally check if there's a keycode ready, and toggle

# DSKY COMP ACTY if there is. Presumably this is inside of a

# loop.

CA NOKEY

EXTEND

SU KEYBUF # Acc will now be zero if no key, non-zero otherwise

EXTEND

BZF EMPTY

CA NOKEY

TS KEYBUF # Mark keycode buffer as empty.

CA CASTATUS # Toggle COMP ACTY.

EXTEND

BZF CAOFF

CA ZERO

TCF CATOGGLE

CAOFF CA TWO

CATOGGLE TS CASTATUS

EXTEND

WRITE 11 # Write to the DSKY lamps

EMPTY NOOP

.

.

.

# Constants

ZERO OCT 0

TWO OCT 2

O37 OCT 37 # Mask with lowest 5 bits set.

NOKEY OCT 40

With this, you actually have an AGC program that

does something, and does it both visibly and testably ... if not

very excitingly.

With this, you actually have an AGC program that

does something, and does it both visibly and testably ... if not

very excitingly.

A slightly sleeker form of this code, called piPeripheral.agc,

which

can be assembled with yaYUL and actually works if it is run in

the AGC simulator, can be found in our GitHub repository.

Actually,

the code in GitHub is not merely a cleaned-up form of the

code above, but in fact implements processing of the

current-timestamp information the sample peripheral program

piPeripheral.py provides in the newly-minted AGC input channels

040-042. (See the end of the preceding section.) What

piPeripheral.agc does with that information (which is a packed

form of the date and time) is to:

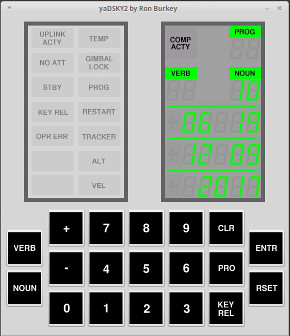

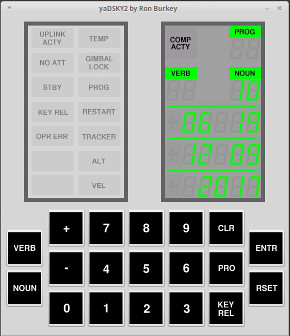

You can actually see what this looks like on a simulated DSKY in

the picture to right. What you see there is:

The piPeripheral.py program will have generated this data

according to the preference settings on the compuer on which

you're running it, which in my case is the U.S. CST time-zone ...

so yes, I was doing this at around 6 in the morning, local time,

on a Saturday. Yawn! I should be paid more (than the

$0 I currently get) for doing this lousy job. :-)

At any rate, assuming one has written such a custom AGC program,

a necessary step before being able to run it in the AGC simulator

is to assemble it with the yaYUL assembler. Exactly how to

find the assembler depends on the particular setup being used, but

assuming you can find it (or better yet, have it in the "PATH"),

assembly is a snap. But suppose, for example, that you

simply want to assemble piPeripheral.agc; assuming you've retained

the same directory setup as in GitHub, and have built the normal

Virtual AGC software too, you could do something like the

following without having to worry about path settings:

The result (if there were no errors, and hopefully there wouldn't be for an unmodified piPeripheral.agc) would be the executable file piPeripheral.agc.bin. If there were assembly errors such as syntax problems or unallocated variables, of course, then you have to fix them ... a topic on which it's difficult to offer any general advice other than to start with a small program that assembles perfectly and slowly work towards having a larger program.cd virtualagc/piPeripheral

../yaYUL/yaYUL piPeripheral.agc

Once the program is assembled, it can be run in the AGC

simulator. This is again a tricky topic, since there are a

variety of ways in which it can be done, and a variety of possible

system configurations. What you would do on a desktop PC is

undoubtedly not the same thing you'd do on the 3D-printed DSKY

mentioned earlier. However, to just do it from a command

line within our software tree as downloaded from GitHub and

successfully built from source, in Linux you could do the

following.

# Start up the AGC simulator with the custom AGC program, in the background, and discard all messages from it.

cd virtualagc/yaAGC

./yaAGC --core="../piPeripheral/piPeripheral.agc.bin" --port=19697 --cfg="../yaDSKY/src/LM.ini" &>/dev/null &

# Start up the DSKY simulator in the background and discard all messages from it.

cd ../yaDSKY2

./yaDSKY2 --cfg="../yaDSKY/src/LM.ini" --port=19698 &>/dev/null &

# Start up the custom peripheral device, in the foreground, and don't discard its messages. You might need

# to install some extra Python modules, such as "sudo pip3 install argparse", if this fails.

cd ../piPeripheral

./piPeripheral.py --port=19699 --time=1

# Now that the custom peripheral has been terminated, clean up the other programs we've started.

killall yaAGC yaDSKY2

On Mac OS, I think it would be a bit trickier than what I'm

written, since I don't think that yaDSKY2 as started this way

would actually accept any keypress events; I'm not sure quite how

to do it properly, though. On Windows, you would have to use

backslashes ('\') in places of the forward slashes if used here

('/'); also, I don't know that using '&' to put the programs

into the background would work, or that "killall" would be

available for killing those programs afterward, so you might want

to run the various programs all in the foreground, in separate

command-line consoles. But obviously, there's a way to do

it, even if I'm too personally lazy to figure it out just

yet. If anyone just wants to inform me of the correct

detailed way of doing things on Mac OS X or Windows, I'd be happy

to include that info here.

This section is under construction.

Beware!

Unfortunately, after some fairly-diligent searching in our document library, I find no convenient tutorial or how-to on writing apps operating under the AGC's multitasking executive. So in this section, I try to cobble together a mini-tutorial on the subject. Alas, I'm no expert, so don't trust my explanation to be either 100% complete or correct, and there may be errors in my meanderings. Feel free to let me know when I've strayed from the facts. I'll confine my remarks to the Block II AGC, though I'm sure that similar considerations apply to Block I systems. (I'm only finite, after all, and these days maybe even less so! If I ever write an autobiography, perhaps I'll title it Less Than Finite.)Aside: For the AGC, there's actually a third approach that's a hybrid of the bare-metal and operating-system approaches, in that it's possible to request the operating system to periodically run a specified task via the AGC's hardware timers that the operating system itself is already controlling. That's done via the idling program's (P00) "request waitlist" (VERB 31) facility. This hybrid approach is available, I think, principally for activating so-called Erasable Memory Programs (EMPs) that are uploaded supplements for the released programs stored in unalterable core memory. I won't cover any of that here, but you can read about it elsewhere.

Important Note: An idea that I may have occasionally promoted myself is providing a new program that's a game, for the purpose of providing the astronauts with at least a little recreation. There's an interesting drawback to that plan, a drawback which it's likely that many other ideas for additional AGC apps may have as well: When the operating system is present, you don't have arbitrary control over what's displayed on the DSKY, nor arbitrary access to the keystrokes received by the DSKY keypad. Rather, the appearance, interpretation, and timing of all of these are controlled by the operating system's PINBALL GAME BUTTONS AND LIGHTS program, and PINBALL works with the display and keyboard entirely under the overarching concept of PROGs, VERBs, and NOUNs. For example, suppose you wanted to provide a Tic Tac Toe game, something which is perfectly possible in bare-metal programming where you have unfettered direct access to all DSKY facilities; the hyperlinked Tic Tac Toe game freely displays numbers on the DSKY, and accepts arbitrary combinations of keypresses +, -, and 0-9. Such a game would have to have a very different user interface if working under the operating system, in which the VERT or NOUN keys would have to be used liberally as well.Nice though aesthetically-horrifying documentation of the multitasking executive system itself can be found in Section II of the LM Primary Guidance Navigation and Control System Study Guide. Indeed, if you can stomach it, it would be worthwhile looking through the entire study guide before proceeding, because it contains a lot of useful details and context that I'm not going to cover below. Note, though, that the study guide was released in January 1967, and some of the information in it, however useful, is not necessarily 100% complete or correct in detail for later versions of AGC flight software. And I wish we had a much cleaner version of the document for you than our only-marginally-readable one, but we don't.

Aside: The Virginia Tech University Libraries, in the James J. Avitabile Papers collection, seem to have a clean copy of the document, in a more-current version than ours. Indeed, VT's collection seems also to have the corresponding CM document. Alas, I don't know any convenient way to my hands on either of these documents for online posting. Anyone wishing to perform a public service and with the stamina to wade through the system should get them for us! Here are the relevant excerpts from the VT finding aid (highlighting mine):

By the way, in the sections that follow, I've provided links to LUMINARY 99/1 (Apollo 11) source code whenever I want to refer to operating-system behavior, but that choice is rather arbitrary and the behavior of your chosen AGC software version could differ in some details.box-folder 17 folder: 2-4

Lunar Module Primary Guidance and Navigation and Control System Student Study Guide

1967

Scope and Content

Content

Familiarization Course (Revision A), Jan. 20, 1967 (2 folders)

System Mechanization, Jan. 27, 1967 (5 folders)

Computer Utility Programs (Revision A), Apr. 5, 1967 (3 folders)

box-folder 18 folder: 1-2

Command Module Primary Guidance and Navigation and Control System Student Study Guide

1966

Scope and Content

Content

Familiarization Course (Revision A), Feb. 15, 1967 (3 folders)

Computer Utility Programs, Mar. 2, 1967 (3 folders)

Each app ("program", "major mode", "MM") installed in the operating system is identified by a unique two-digit decimal number that's used to activate the app. For example, to activate the idling routine (P00), the astronaut keys VERB 37 ENTR 0 0 ENTR into the DSKY, at which point the DSKY displays that the "PROG" is 00 to indicate that the idling routine is currently active. If your new app is ever going to be activated by the astronaut, it too must be associated with one of these 2-digit code numbers, different from all of the preexisting apps.Note: Step 5 below describes how to automatically start your app when the AGC starts or restarts. Steps 2 and 3, I believe, are relevant to the situation in which you'd like the astronaut to be able to manually start your app via the commonly-used method of VERB 37 ("change major mode") on the DSKY. If you want only to have your app autostart, then perhaps you can skip Steps 2 and 3, and proceed directly to Step 4 below. Even if you skip these steps, I think it should still be possible to start your app from the DSKY, using the more-obscure and more-irksome process of getting into idling mode (VERB 37 ENTR 00 ENTR), starting a "request executive" operation (VERB 30 ENTR), and then supplying low-level characteristics of the multitasking job you want to start (NOUN 26), such as the job priority, whether a VAC is needed, the starting address of your app, and the fixed/erasable memory banks associated with your app. As it happens, these are all of the same kinds of data you need for Step 3 below, so there may not be much advantage in skipping past it. An advantage of this alternate approach is that (I think!) it allows your app's code to be located in the memory superbanks 40-43, whereas the approach I outline below does not. Anyway, you can read more about this alternative method of starting your app from the DSKY here.

Unfortunately, we have only a limited selection of these kinds of

documents in the library, and certainly don't have them for every

mission you might choose to use as your "operating system", so you

may still have to resort to determining the interpretations of the

2-digit program codes the hard way.

For AGC software versions other than ARTEMIS or SKYLARK, there

are 3 tables:

Additionally, at label NOV37MM, there is a count of the

number of entries in the tables, which is the number of major

modes minus 1 (for the ubiquitous mod 00). So when you add

entries to the tables listed above to include your new app, you

have to increment the value at NOV37MM by 1.

Note that these steps are inverted if/when you choose to delete

existing major modes in order to recover memory. I.e.,

entries for the programs you remove must also be deleted from the

three tables, and NOV37MM must be decremented for each

program removed.

For ARTEMIS or SKYLARK, on the other hand, job priorities are

omitted from table PREMM1, which which saves enough bits

to allow tables PREMM1 and DNLADMM1 to be

consolidated. This saves memory, but makes it harder for you

to define your own custom telemetry downlists, if you desired to

do so. The value for NOV37MM is figured

automatically by the assembler, so you do not have to maintain it.

You can add the new code directly into an existing source-code

file for your chosen "operating system", or else you can create a

new AGC source-code file and store it in the same folder with all

of the other source files for your chosen operating system.

If you do want to create a new source-code file, as I imagine is

probably the case, be sure to add it in MAIN.agc to all of the

other source-code files comprising the operating system. Add

the new file to the end of the list of source-code files

(in MAIN.agc), to insure that the assembled forms of the

preexisting files retain similar addressing to what they had

before your new code was added, rather than all being displaced

upward in memory to accommodate the new code. (They may or

may not be somewhat displaced anyway, due to adding new entries in

the major-mode tables as described above, or other modifications

described below.)

What are the characteristics you need to build into your app's

source code to exist harmoniously in the operating system?

That's what the subsections below cover.

Your new source code should begin by telling the assembler to

place the code in the memory banks you've chosen. For the

sake of discussion, let's suppose that:

Simple-minded code for your app's lead-in might look like this:

BANK 15

EBANK= 4

MYAPP ...

.

.

.

I call this code "simple-minded", because in practice you might

find that it's better practice to use symbolic names for the

memory banks, rather than hard-coding the constants 15 and 4, and

there are additional pseudo-ops than just BANK and EBANK=

to accomplish this. But simple-minded way is certainly a

valid approach.

The code for your app can use either basic assembly language or

interpreter language, or intermix them. Note that each job

being multitasked by the EXECUTIVE —

including your own app — is assigned its own separate "vector

accumulator" (VAC) for use with interpreted code. In other

words, interpretive code in your app has a VAC that does not

conflict with the VAC of other running jobs.

Multitasking in the AGC "operating system" is cooperative rather

than preemptive. In other words, the EXECUTIVE doesn't

successively give competing jobs time-slices for execution and

forcibly change control from one job to another when those

time-slices are complete. Apparently, time-slices do not

exist as such. Rather, each job (such as your app) must

periodically check whether a job of a higher priority is pending,

and meekly return control the EXECUTIVE if so. But if no

higher-priority job is pending, the currently-executing job can

just keep going as long as it likes without surrendering to the

executive.

Aside: The operating system's multitasking scheme should not be confused with low-level interrupt-driven software that performs operations such as servicing hardware timers, asynchronously getting keystrokes from the DSKY or uplink, and so on. CPU interrupt servicing is a completely separate mechanism from operating-system multitasking. But for example, an interrupt-service routine operating from a CPU timer could schedule a high-priority multitasked job, which would later cause a lower-priority multitasked job to relinquish control to the EXECUTIVE.

A pending job of higher priority is communicated to the

currently-executing job via the NEWJOB variable, which

will have either the value +0 (to indicate that there is no

higher-priority job) or a value >0 (to indicate that there is

indeed a higher-priority job pending). Negative (or -0)

values never appear. While there are a number of ways to

respond to these conditions, a typical technique is for each job

to periodically use the code

# If in the midst of a block of basic assembly-language code.

CCS NEWJOB

TC CHANG1

or else

# If in the midst of a block of interpreter-language code.When the EXECUTIVE eventually returns control to your app, execution will resume at the location following the TC CHANGx instruction.

CCS NEWJOB

TC CHANG2

There are conditions under which your app may wish to voluntarily

return control to the EXECUTIVE and put itself to sleep. For

example, it might want to wait on i/o without hogging CPU cycles

that could profitably be used by other jobs. Your app does

this using code similar to the following:

CAF ... address at which to reenter at next time-slice ...or

TCF JOBSLEEP

CAF ... address at which to reenter at next time-slice ... TC JOBSLEEPOnce your app is asleep, however, it will no longer receive time-slices and hence will no longer execute until some code external to it wakes it up by means of a call to JOBWAKE.

If your app isn't intended to run forever, then eventually you'll

want your app to terminate itself and receive no additional time

slices. Your app does this like so:

TCF ENDOFJOBor

TC ENDOFJOB

Access to the DSKY (display/keyboard) is provided by the

flight-software in the following flight-software code sections:

The DISPLAY_INTERFACE_ROUTINES are built atop the

more-fundamental PINBALL_GAME_BUTTONS_AND_LIGHTS functionality.

You would think that given the overwhelming importance of these

routines, there would be documentation someplace in the form of a

tutorial that told you how to incorporate them into your

program. Alas, that does not appear to be the case, so we'll

have to work out our own guide.

When programming an app that runs under the AGC "operating

system", your code does not have an unrestricted ability to read

keystrokes from the DSKY, nor to display whatever it likes on the

DSKY's display. In point of fact, it cannot detect those

keystrokes at all. Rather, all access of the DSKY is modeled

on the notion of "verbs" and "nouns" that pervades all discussion

of how the astronauts interact with the DSKY, and all interactions

with the DSKY are forced by PINBALL into that basic scheme.

"Verbs" and "nouns" in this context refer not to English words

that are verbs or nouns, but rather to 2-digit codes recognized by

the operating system. The different verbs refer to the context

of the data is going to be input or output; i.e., to how that data

is used. Whereas the different nouns refer to the format

of that data.

For example: Suppose the desired user interface of

your app does nothing but waits for the astronaut to key in an

endless sequence of octal numbers on the DSKY keypad. Efficient

input via the DSKY would look like this:

... the first octal number ... ENTR

... the second octal number ... ENTR

... the third octal number ... ENTR

etc.

But there is no way to implement such a thing under the AGC

operating system. Rather, the astronaut must either input

this data via the specific "verbs" and "nouns" already defined by

the AGC operating system, or else your app must implement new

previously-nonexistent types of verbs and nouns. Using

existing verbs and nouns, the astronaut might enter the

data via the keystrokes

VERB 21 NOUN 46 ... the first octal number ... ENTR

VERB 21 NOUN 46 ... the second octal number ... ENTR

VERB 21 NOUN 46 ... the third octal number ... ENTR

etc.

But regardless of the particular verbs and nouns used, your app

is never informed by the operating system that the VERB key has

been pressed, nor that the NOUN key has been pressed, nor the ENTR

key, nor any of the digit keys; only that a complete, new number

is now available. Nor does your app control where or how or

even if these digits are displayed on the DSKY while the

astronaut is inputting the data.

The types of verbs and nouns recognized by the operating system

evolved somewhat over the evolution of the AGC flight software, so

it's not possible to give a single authoritative list of

them. Instead, you have to consult the source code or

documentation for the specific AGC software version you've chosen

to use as your operating system. That said, it was usually

the case that new types of verbs or nouns were merely added over

time, rather than that the interpretation of any given verb or

noun changed. Thus there plenty of verbs and nouns (like the

VERB 21 and the NOUN 46 in the example above) that were

identically present in all AGC software versions.

The

study guide tells us that "The VERB codes are divided into

two groups — Ordinary and Extended. The ordinary verbs generally

are involved in the manipulation (loading, display, etc.) of data.

The extended verbs, in general, are used for initiation of actions

(moding requests, equipment operation, etc.)." You'll also

see the term "regular verbs" as a synonym for "ordinary

verbs". Additionally:

Here, for example, are the complete verb tables from SUNDANCE

306, in which (barring miscounts on my part) you can see 11 spare

regular verbs and 15 spare extended verbs which you could

potentially define anew for your app. The entries in the

table, obviously, point to subroutines implementing the particular

types of verbs.

VERBTAB CADR GODSPALM # VB00 ILLEGAL

CADR DSPA # VB01 DISPLAY OCT COMP 1 (R1)

CADR DSPB # VB02 DISPLAY OCT COMP 2 (R1)

CADR DSPC # VB03 DISPLAY OCT COMP 3 (R1)

CADR DSPAB # VB04 DISPLAY OCT COMP 1,2 (R1,R2)

CADR DSPABC # VB05 DISPLAY OCT COMP 1,2,3 (R1,R2,R3)

CADR DECDSP # VB06 DECIMAL DISPLAY

CADR DSPDPDEC # VB07 DP DECIMAL DISPLAY (R1,R2)

CADR GODSPALM # VB08 SPARE

CADR GODSPALM # VB09 SPARE

CADR DSPALARM # VB10 SPARE

CADR MONITOR # VB11 MONITOR OCT COMP 1 (R1)

CADR MONITOR # VB12 MONITOR OCT COMP 2 (R1)

CADR MONITOR # VB13 MONITOR OCT COMP 3 (R1)

CADR MONITOR # VB14 MONITOR OCT COMP 1,2 (R1,R2)

CADR MONITOR # VB15 MONITOR OCT COMP 1,2,3 (R1,R2,R3)

CADR MONITOR # VB16 MONITOR DECIMAL

CADR MONITOR # VB17 MONITOR DP DEC (R1,R2)

CADR GODSPALM # VB18 SPARE

CADR GODSPALM # VB19 SPARE

CADR GODSPALM # VB20 SPARE

CADR ALOAD # VB21 LOAD COMP 1 (R1)

CADR BLOAD # VB22 LOAD COMP 2 (R2)

CADR CLOAD # VB23 LOAD COMP 3 (R3)

CADR ABLOAD # VB24 LOAD COMP 1,2 (R1,R2)

CADR ABCLOAD # VB25 LOAD COMP 1,2,3 (R1,R2,R3)

CADR GODSPALM # VB26 SPARE

CADR DSPFMEM # VB27 FIXED MEMORY DISPLAY

CADR GODSPALM # VB28 SPARE

CADR GODSPALM # VB29 SPARE

CADR VBRQEXEC # VB30 REQUEST EXECUTIVE

CADR VBRQWAIT # VB31 REQUEST WAITLIST

CADR VBRESEQ # VB32 RESEQUENCE

CADR VBPROC # VB33 PROCEED WITHOUT DATA

CADR VBTERM # VB34 TERMINATE CURRENT TEST OR LOAD REQ

CADR VBTSTLTS # VB35 TEST LIGHTS

CADR SLAP1 # VB36 FRESH START

CADR MMCHANG # VB37 CHANGE MAJOR MODE

CADR GODSPALM # VB38 SPARE

CADR GODSPALM # VB39 SPARE

LST2FAN TC VBZERO # VB40 ZERO (USED WITH NOUN 20 OR 72 ONLY)

TC VBCOARK # VB41 COARSE ALIGN (USED WITH NOUN 20 OR 72 ONLY)

TC IMUFINEK # VB42 FINE ALIGN IMU

TC IMUATTCK # VB43 LOAD IMU ATTITUDE ERROR METERS.

TC RRDESEND # VB44 TERMINATE CONTINUOUS DESIGNATE

TC V45 # VB45 W MATRIX MONITOR

TC ALM/END # VB46 SPARE

TC V47TXACT # VB47 AGS INITIALIZATION

TC DAPDISP # VB48 LOAD A/P DATA

TCF CREWMANU # VB49 START AUTOMATIC ATTITUDE MANEUVER

TC GOLOADLV # VB50 PLEASE PERFORM

TC ALM/END # VB51 SPARE

TC GOLOADLV # VB52 PLEASE MARK X - RETICLE.

TC GOLOADLV # VB53 PLEASE MARK Y - RETICLE.

TC GOLOADLV # VB54 PLEASE MARK X OR Y - RETICLE

TC ALINTIME # VB55 ALIGN TIME

TC TRMTRACK # VB56 TERMINATE TRACKING - P20 + P25

TC ALM/END # VB57 SPARE

TC ALM/END # VB58 SPARE

TC ALM/END # VB59 SPARE

TC DAPATTER # VB60 DISPLAY DAP ATTITUDE ERROR

TC LRPOS2K # VB61 COMMAND LR TO POSITION 2.

TC R04 # VB62 SAMPLE RADAR ONCE PER SECOND

TC TOTATTER # VB63 DISPLAY TOTAL ATTITUDE ERROR

TC ALM/END # VB64 SPARE

TC SNUFFOUT # VB65 DISABLE U,V JETS DURING DPS BURNS.

TC ATTACHED # VB66 ATTACHED MOVE THIS TO OTHER STATE

TC ALM/END # VB67 SPARE

TC ALM/END # VB68 SPARE

TC VERB69 # VB69 FORCE A HARDWARE RESTART

TC V70UPDAT # VB70 UPDATE LIFTOFF TIME.

TC V71UPDAT # VB71 UNIVERSAL UPDATE - BLOCK ADDRESS.

TC V72UPDAT # VB72 UNIVERSAL UPDATE - SINGLE ADDRESS.

TC V73UPDAT # VB73 UPDATE AGC TIME (OCTAL).

TC DNEDUMP # VB74 INITIALIZE DOWN-TELEMETRY PROGRAM FOR ERASABLE DUMP.

TC OUTSNUFF # VB75 ENABLE U,V JETS DURING DPS BURNS.

TC MINIMP # VB76 MINIMUM IMPULSE MODE

TC NOMINIMP # VB77 RATE COMMAND MODE

TC R77 # VB78 START LR SPURIOUS RETURN TEST

TC R77END # VB79 TERMINATE LR SPURIOUS RETURN TEST

TC LEMVEC # VB80 UPDATE LEM STATE VECTOR

TC CSMVEC # VB81 UPDATE CSM STATE VECTOR

TC V82PERF # VB82 REQUEST ORBIT PARAM DISPLAY (R30)

TC V83PERF # VB83 REQUEST REND PARAM DISPLAY (R31)

TC R32 # VB84 START TARGET DELTA V (R32)

TC ALM/END # VB85 SPARE

TC ALM/END # VB86 SPARE

TC ALM/END # VB87 SPARE

TC ALM/END # VB88 SPARE

TC V89PERF # VB89 ALIGN XORZ LEM AXIS ALONG LOS (R63)

TC V90PERF # VB90 OUT OF PLANE RENDEZVOUS DISPLAY

TC GOSHOSUM # VB91 DISPLAY BANK SUM.

TC SYSTEST # VB92 OPERATE IMU PERFORMANCE TEST.

TC WMATRXNG # VB93 CLEAR RENDWFLG

TC ALM/END # VB94 SPARE

TC UPDATOFF # VB95 NO STATE VECTOR UPDATE ALLOWED

TC VERB96 # VB96 INTERRUPT INTEGRATION AND GO TO POO

TC ALM/END # VB97 SPARE

TC ALM/END # VB98 SPARE

TC GOLOADLV # VB99 PLEASE ENABLE ENGINE

Nouns, meanwhile, are categorized as either "normal" (codes 00-39) or "mixed" (codes 40-99). The distinction, as explained by the study guide is that "Normal Nouns refer to data stored in sequential memory registers and the data contained in or to be loaded into these registers must use the same scaling. ... The other type of noun code, the Mixed Noun, refers to data which is not necessarily located in sequential memory registers nor necessarily use the same scaling." And as with the verbs, these may differ a little from one incarnation of the AGC flight software to the next. For all AGC versions concerning us here, the nouns are implemented primarily in PINBALL NOUN TABLES (look for the tables at labels NNADTAB and NNTYPTAB) and documented in ASSEMBLY AND OPERATION INFORMATION (and often in the study guide). The NNADTAB table points to subroutines implementing the individual nouns, whereas the NNTYPTAB table entries for those same nouns are numerical values whose bitfields provide the formats for up to 3 numerical components (corresponding to the 3 5-digit registers displayed on the DSKY). For illustrative purposes, the SUNDANCE 306 NNTYPTAB table reads:

# NN NORMAL NOUNS

NNTYPTAB OCT 00000 # 00 NOT IN USE

OCT 04040 # 01 3COMP FRACTIONAL

OCT 04140 # 02 3COMP WHOLE

OCT 04102 # 03 3COMP CDU DEGREES

OCT 00000 # 04 SPARE

OCT 00504 # 05 1COMP DPDEG(360)

OCT 02000 # 06 2COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 04000 # 07 3COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 04000 # 08 3COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 04000 # 09 3COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 00000 # 10 1COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 00000 # 11 SPARE

OCT 00000 # 12 SPARE

OCT 00000 # 13 SPARE

OCT 04140 # 14 3COMP WHOLE

OCT 00000 # 15 1COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 24400 # 16 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 04102 # 17 3COMP CDU DEG

OCT 04102 # 18 3COMP CDU DEG

OCT 04102 # 19 3COMP CDU DEG

OCT 04102 # 20 3COMP CDU DEGREES

OCT 04140 # 21 3COMP WHOLE

OCT 04102 # 22 3COMP CDU DEGREES

OCT 00000 # 23 SPARE

OCT 24400 # 24 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 04140 # 25 3COMP WHOLE

OCT 04000 # 26 3COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 00140 # 27 1COMP WHOLE

OCT 00000 # 28 SPARE

OCT 00000 # 29 1COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 24400 # 30 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24400 # 31 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24400 # 32 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24400 # 33 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24400 # 34 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24400 # 35 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24400 # 36 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24400 # 37 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00000 # 38 SPARE

OCT 00000 # 39 SPARE

# NN MIXED NOUNS

OCT 24500 # 40 3COMP MIN/SEC, VEL3, VEL3 (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 00542 # 41 2COMP CDU DEG, ELEV DEG

OCT 24410 # 42 3COMP POS4, POS4, VEL3(DEC ONLY)

OCT 20204 # 43 3COMP DPDEG(360), DPDEG(360), POS4 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00410 # 44 3COMP POS4, POS4, MIN/SEC(NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 10000 # 45 3COMP WHOLE, MIN/SEC, DPDEG(360) (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 00000 # 46 1COMP OCTAL ONLY

OCT 00306 # 47 2COMP WEIGHT2 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 01367 # 48 2COMP TRIM DEG2 FOR EACH(DEC ONLY)

OCT 00510 # 49 2COMP POS4, VEL3 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00010 # 50 3COMP POS4, MIN/SEC, MIN/SEC (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 00204 # 51 2COMP DPDEG(360), DPDEG(360) (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00004 # 52 1COMP DPDEG(360)

OCT 20512 # 53 3COMP VEL3, VEL3, POS4 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 10507 # 54 3COMP POS5, VEL3, DPDEG(360) (DEC ONLY)

OCT 10200 # 55 3COMP WHOLE, DPDEG(360), DPDEG(360) (DEC ONLY)

OCT 20200 # 56 3COMP WHOLE, DPDEG(360), POS4 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00010 # 57 1COMP POS4 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24510 # 58 3COMP POS4, VEL3, VEL3 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24512 # 59 3COMP VEL3 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 60512 # 60 3COMP VEL3, VEL3, COMP ALT (DEC ONLY)

OCT 54000 # 61 3COMP MIN/SEC, MIN/SEC, POS7 (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 24012 # 62 3COMP VEL3, MIN/SEC, VEL3 (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 60512 # 63 3COMP VEL3, VEL3, COMP ALT (DEC ONLY)

OCT 60500 # 64 3COMP 2INT, VEL3, COMP ALT (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 00000 # 65 3COMP HMS (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00016 # 66 2COMP LANDING RADAR ALT, POSITION (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 53223 # 67 3COMP LANDING RADAR VELX, Y, Z

OCT 60026 # 68 3COMP POS7, MIN/SEC, COMP ALT (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 24000 # 69 3COMP WHOLE, WHOLE, VEL3 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 0 # 70 3COMP OCTAL ONLY FOR EACH

OCT 0 # 71 3COMP OCTAL ONLY FOR EACH

OCT 00102 # 72 2COMP 360-CDU DEG, CDU DEG

OCT 00102 # 73 2COMP 360-CDU DEG, CDU DEG

OCT 10200 # 74 3COMP MIN/SEC, DPDEG(360), DPDEG(360) (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 60500 # 75 3COMP MIN/SEC, VEL3, COMP ALT (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 00410 # 76 3COMP POS4, POS4 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00500 # 77 2COMP MIN/SEC, VEL3 (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 00654 # 78 2COMP RR RANGE, RR RANGE RATE

OCT 00102 # 79 3COMP CDU DEG, CDU DEG, WHOLE (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00200 # 80 2COMP WHOLE, DPDEG(360)

OCT 24512 # 81 3COMP VEL3 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24512 # 82 3COMP VEL3 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24512 # 83 3COMP VEL3 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24512 # 84 3COMP VEL3 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24512 # 85 3COMP VEL3 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 24512 # 86 3COMP VEL3 FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 00102 # 87 2COMP CDU DEG FOR EACH

OCT 0 # 88 3COMP FRAC FOR EACH (DEC ONLY)

OCT 16143 # 89 3COMP DPDEG(90), DPDEG(90), POS5 (DEC ONLY)

OCT 10507 # 90 3COMP POS5, VEL3, DPDEG(360) (DEC ONLY)

OCT 62010 # 91 3COMP POS4, MIN/SEC, DPDEG(XXXX.X) (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 62000 # 92 3COMP SPARE, MIN/SEC, DPDEG(XXXX.X) (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 06143 # 93 3COMP DPDEG(90) FOR EACH

OCT 62010 # 94 3COMP POS4, MIN/SEC, DPDEG(XXXX.X) (NO LOAD, DEC ONLY)

OCT 04102 # 95 3COMP CDU DEG FOR EACH

OCT 04102 # 96 3COMP CDU DEG FOR EACH

OCT 00000 # 97 3COMP WHOLE FOR EACH

OCT 00000 # 98 3COMP WHOLE, FRAC, WHOLE

OCT 01572 # 99 3COMP POS9, VEL4 (DEC ONLY)

This is significant to you, of course, only if you intend to create new types of nouns, which in spite of the explanations above isn't something I foresee anyone doing. For that reason — and because it's reasonably difficult to do so — , I admit that I have not actually made the effort to work out how precisely how to deal with the numerical codes in NNTYPTAB, nor the codes in various other associated tables within PINBALL NOUN TABLES, namely SFINTAB and SFOUTAB. In other words, I don't actually know in more detail at the moment how to implement a new noun type. If anyone does want to define new noun types, let me know what you figure out or if you need help figuring it out.

As far as actually incorporating any of this into your app is

concerned, TBD

If you want your new app to be automatically restarted when an

abort occurs that restarts the computer, you'll have to take steps

to periodically save its internal state, and to add the app to the

so-called "restart tables". This feature is the kind of

thing that allowed the AGC to recover from the "1201" and "1202"

alarms that occurred during the Apollo 11 landing.

Since I don't fully understand this topic yet, I'll defer

discussion of it. Although frankly, I doubt that it's of too

much interest anyway in a simulation environment.

The AGC hardware incorporates a so-called "night watchman"

circuit that monitors the activity of the AGC software and

triggers a system restart if it appears that the software has

become unresponsive. The term "night watchman" was specific

to the AGC development team, and was what might more-commonly be

known today as a watchdog

timer. If you execute your new app+operating

system on a physical AGC or a simulation of AGC electronics, your

software will have to periodically service the night watchman

circuit to insure that it doesn't spontaneously restart the AGC.

Specifically, the night watchman circuit triggers a restart if

the software fails to access address 67 (octal) at least once

every 0.64 second. This address is given the symbolic name NEWJOB.

As mentioned above, each job is supposed to periodically query NEWJOB

anyway, so if that has been implemented properly you have nothing

to worry about.

How might such a night-watchman failure occur? Well,

perhaps your app disables the CPU's interrupts without reenabling

them afterward. Or perhaps it uses more than 0.64 seconds

between queries of NEWJOB.

Note, though, that the software-only AGC emulator (known as yaAGC)

provided by the Virtual AGC Project does not itself include a

simulated night-watchman circuit, and thus your app wouldn't need

to service the night watchman if your intention was to run your

app only in the VirtualAGC simulation environment.

As implemented so far by the steps above, you'll have a modified

AGC flight program in which the astronaut could optionally start

your new app manually by means of DSKY commands. For

example, if your new app has been implemented to have the 2-digit

code 99, then the astronaut could start the app by means of the

keystrokes VERB 37 ENTR 99 ENTR.

But perhaps that's not good enough for you, and you'd prefer that

your app just start up automatically without astronaut

participation. In that case, we need to add some additional

instructions to the flight software to make that happen.

What are those instructions? There are two cases: Does

your app need a "vector accumulator" (VAC) for arithmetical

operations performed by the INTERPRETER, or does it not? Of

course, if your app has no interpreter language in it, then it

certainly does not need a VAC.

Let's suppose that (as above) your app's code is at label MYAPP,

in fixed-memory bank 15, with variables (other than the VAC, if

any) in erasable-memory bank 4. Let's suppose also that you

want your app to have job-priority 3. If your app needs a

VAC, then you could start its job with the instructions

CAF 3

TC FINDVAC

EBANK= 4

2CADR MYAPP

whereas if no VAC is needed,

CAF 3

TC NOVAC

EBANK= 4

2CADR MYAPP

Note the use of the EBANK= pseudo-op, which we also

used earlier, explaining that it tells the assembler which

erasable-memory bank is currently in use. The EBANK=

setting generally stays in effect until another EBANK=

(or SETLOC) is encountered, which might cause you to

worry that the EBANK= has to be undone in order to avoid

messing up whatever lines of code follow the instructions

above. But fortunately not! Whenever a 2CADR

pseudo-op immediately follows an EBANK=, the assembler

knows to use the selected erasable-bank setting only for the 2CADR,

while returning for subsequent lines to whatever erasable-bank

setting had been previously in place.

Where should you put these instructions to insure that

they are executed at startup? TBD

../yaYUL/yaYUL --unpound-page MAIN.agc >MAIN.agc.lst(In Microsoft Windows, you'd need to use backward slashes. I'm assuming that whether you're using Linux, Mac OS, or Windows, that you've built Virtual AGC for whatever computer system you're running, and thus have available its programs like yaYUL, yaAGC, VirtualAGC, and so on.)

I don't really know how you intend to run the simulation

containing the AGC flight software with your new app added to

it. Perhaps you want to run it in Orbiter. Or perhaps

you want to run it on an AGC you're physically emulating with

ASICs. If so, I have no insight.

Let's suppose, however, you want to run it in Virtual AGC's

software-only simulation environment. Once upon a time, our

VirtualAGC GUI wrapper allowed you to specify and run your

own custom AGC program, which would be ideal for this

scenario. Unfortunately, that capability was dropped many

years ago. However, we can still fool VirtualAGC

anyway to do most of the work for us. Here's how.

To do the same thing from a command line ...

cd /mnt/STORAGE/home/rburkey/VirtualAGC/Resources

./simulate

The contents of "simulate" are:

#!/bin/sh

PIDS=

rm LM.core

rm CM.core

sleep 0.2

../bin/yaAGC --core="source/Sundance306ish/Sundance306ish.bin" --port=19797 --cfg=CM.ini &

PIDS="$! ${PIDS}"

../bin/yaDSKY2 --x=4645 --y=5 --cfg=CM.ini --port=19797 &

PIDS="$! ${PIDS}"

sleep 0.2

export PIDS

ps auxww | egrep '\.\./bin/|VirtualAGC.tcl'

../bin/SimStop

The final step in the preceding section, "Enjoy!", is of course

errant nonsense, because in real life your program isn't going to

actually work until you've done a lot of debugging on it.

The good news is that any version of AGC software can be debugged

via the Code::Blocks graphical

debugger, as long as a suitable configuration file has been

produced. (They can also be debugged using built-in gdb

console-style commands from a yaAGC command line, albeit

usually with greater difficulty. You don't actually use

gdb for the debugging, just its "style".)

Of course, you must install Code::Blocks on your computer

for this debugging option to be available.

One requirement for graphical debugging via Code::Blocks

is that there be an available Code::Blocks configuration

file for the AGC software version you want to debug. If

you're running Linux, Mac OS, or Windows (with MSYS2), there's a

script in the Virtual AGC source tree that should create such a

configuration file for you. It requires that your

source-code folder (say, MYAPP) is stored at the top level of the

Virtual AGC source tree. From a command line, just cd

into the Virtual AGC source tree, and use the command

./createCBP.sh MYAPP

and you should find that the configuration file MYAPP/MYAPP.cbp

has been created. If this technique fails for you, I'd

suggest just getting the configuration file for the AGC version

you're basing your software on (such as

Luminary099/Luminary099.cbp), copying/renaming it to

MYAPP/MYAPP.cbp, and editing it in a text-editing program.

Recognizing that the list of AGC source-code files is given within

MYAPP/MAIN.cbp, the changes you need to make to MYAPP/MYAPP.cbp

should be obvious upon inspection, even if potentially tedious.

To start the graphical debugger for MYAPP, you should be able to

navigate in your desktop file-system browser to your MYAPP/

folder, and double-click on the file MYAPP.cbp.

Techniques for actually using Code::Blocks (or gdb-style

commands) or for debugging AGC programs in general are far outside

the scope of what I want to discuss here. Some additional

explanation appears on our download

page (within the context of our Virtual AGC virtualbox VM),

at the same time pointing out additional resources having more

detail, both general and Virtual-AGC-specific.