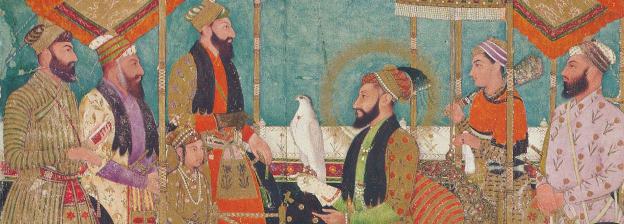

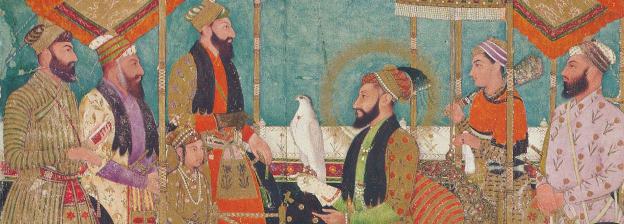

The four sons of Shah-Jahan who made ready in 1657 to fight for their apparently dying father’s throne were Dara the eldest, a man of forty-two, Shuja, a year younger, Aurangzib, almost thirty-nine, and Murad-Bakhsh, the youngest, then in his thirty-fourth year6. Their characters have been drawn by Bernier, who knew Dara and Aurangzib personally, and acted as physician to each in succession. Dara Shukoh, he tells us, was not wanting in good qualities, and could be both gracious and generous; but he was inordinately conceited and self-satisfied, very proud of his intellectual gifts, and extremely intolerant of advice and contradiction, which easily roused his imperious and violent Mughal temper. Though

nominally a Muhammadan in outward forms, he was really all things to all men, and prided himself on his breadth of view; accepting philosophical ideas from the Brahmans who lived upon his bounty, and lending a sympathetic ear to the religious suggestions of the Reverend Father Buzée of the Company of’ Jesus. He wrote treatises on comparative theology, in which he maintained that ‘infidelity’ and Islam were almost twin sisters.

It has been suggested that Dara’s wide religious sympathies were assumed for political reasons, in order to win over the tributary Rajas, and the Christians who furnished all the best gunners for the artillery, with a view to the coming struggle for the throne: but it is more likely that he was honestly trying, according to his lights, to tread the path wherein Akbar had walked. As will be seen, Dara’s ‘emancipated’ ideas did him more harm than good, and formed a pretext for his destruction. But apart from his creed, or agnosticism, he was a nervous, sensitive, impulsive creature, full of fine feelings and vivid emotions, never master of himself or of others, and liable to lose his self-control just when cool judgement was most necessary. He might have been a poet or a transcendental philosopher; he could. never have become a Ruler of India.

His next brother, Shuja, had more will and less elevation of character than Dara. He was brave, discreet, subtle, and a dexterous diplomatist. He knew how to bribe the Hindu chiefs, and succeeded

in interesting the great Maharaja of Marwar, Jaswant Singh, in his cause. He professed himself a Shi’i, or follower of Ali, in order to secure the adhesion of the powerful Persian lords. But he had a fatal weakness: he was too much a slave to his pleasures; and once surrounded by his women, who were exceedingly numerous, he would pass whole days and nights in dancing, singing, and drinking wine. He presented his favourites with rich robes, and increased or diminished their allowances as the passing fancy of the moment prompted. No courtier who consulted his own interest would attempt to detach him from this mode of life: the business of government [he was viceroy of Bengal] therefore often languished, and the affections of his subjects were in a great measure alienated7.’ It is recorded of the great Khalif Al-Mansdr, the true founder of the ‘AbbAsid empire, that when he was engaged in a war, he never looked upon the face of woman till he had triumphed. Shuja might well have emulated his example. No Mughal sovereign who shut himself up in the seraglio, and neglected to show himself constantly to his subjects and listen to their complaints, had any chance of retaining his ascendancy over them. Shuja’s zenana was the prison of his career.

Murad-Bakhsh, the youngest son of Shah-Jahan, was a gallant swashbuckler, brave as a lion, frank

and open as the day; a fool in politics, a despiser of statecraft, and a firm believer in ruddy steel. He was the terror of the battle-field, and the best of good fellows over a bottle. No one could be better trusted in a melley; none was more fatuous in council or more reckless in a debauch. The hereditary passion for wine, which had descended from Babar to his posterity, found a willing victim in this valiant boor. His name justified itself in accordance with his mental limitations: his desires’ were indeed attained,’ but they were the sort of desires which lead to perdition.

Two princesses played an important part in the intrigues which circled round the sick-bed of their father. The elder, Jahan-Ara, or ‘World-adorner,’ known as Begam Sahib, or Princess Royal, was her father’s darling. Beautiful and ‘of lively parts,’ she devoted herself to the solace of his old age, won his unbounded confidence, and, in the absence of any preeminent Queen, exerted unlimited influence in the Mughal Court. No intrigue or piece of jobbery could prosper without her aid, and the handsome presents she was always receiving from those who had anything to gain from the Emperor, added to her magnificent pin-money, made her extremely wealthy. She was condemned to the usual fate of Mughal princesses, the state of single blessedness, because no alliance in India was considered worthy of the Princess Royal, or because no great Lord cared to burden himself with the oppressive glory of becoming the husband of an imperious wife. Princesses did not conduce to

domestic peace in a polygamous household. The Princess Royal is said, however, like some other grandes et honnêtes dames de par la monde, to have consoled herself. In politics, she was a warm ally of Dara, and exerted all her influence with the King on his behalf. Her younger sister, Raushan-Ara, or Brilliant Ornament,’ on the other hand, was a staunch supporter of Aurangzib, and cordially hated the Princess Royal and her eldest brother. So long as Dara lived, she had little power, but she watched zealously over Aurangzib’s interests, and kept him constantly in formed of all that went on at Court. She was not so handsome as her sister; but this did not prevent her having her little affairs, without which a spinster’s life in the zenana had few distractions.

Aurangzib, the third son of Shah-Jahan, was born on the night of the 4th of November, 1618, at Dhud, on the borders of Malwa, nearly half-way between Baroda and Ujjain. His father was at that time Viceroy of the Deccan province, but the future emperor was only two years old when Shah-Jahan fell into disgrace with the Court, and was forced to fly, fighting the while, through Telingana and Bengal, and three or four years passed before he could again resume his place in the Deccan. At last he offered his submission and apologies to Jahangir, and was allowed to remain undisturbed , on condition that he sent two of his sons, Dara and Aurangzib, as hostages to the Court at Agra (1625). Nothing is known of the life of the child during the years of civil war, or

of his captivity under the jealous eyes of Queen Nur-Jahan. Nor is anything recorded of his boyhood, from the day when, at the age of nine, he saw his father ascend the throne, to the year 1636, when the youth of seventeen was appointed to the important office of Governor of the Deccan. – The childhood of an eastern prince is usually uneventful. Aurangzib doubtless received the ordinary education of a Muslim, was-taught his Koran, and well grounded in the mysteries of Arabic grammar and the various scholastic accomplishments which still make up the orthodox body of learning in the East. He certainly acquired a facility in verse, and the prose style of his Persian letters is much admired in India. In later years he complained of the narrow course of study set before him by his ignorant – or at least conventional – tutor8, and drew a sketch of what the education of a Prince ought to be. To his early religious training, however, he probably owed his decided bent towards Muslim puritanism, which was at once his distinction and his ruin.

Aurangzib’s early government of the Deccan was a nominal rule. The young prince seems to have been more occupied with thoughts of the world to come than with measures for the subjugation of the earth beneath his eyes. Possibly the pomp and empty pageantry of his father’s sumptuous Court set the earnest young mind thinking of the ‘vanity of human wishes ‘; or some judicious friend may have instilled

into the receptive soul the painful lessons to be drawn from the careless self-indulgence of too many of his royal relatives. Whatever the influence, it is clear that he had early learnt to look upon life as a serious business. In 1643, when only twenty-four, he announced his intention of retiring from the world, and actually took up his abode in the wild regions of the Western Ghats (where Dr. Fryer was shown his retreat) and adopted the rigorous system of self-mortification which distinguished the fakir or mendicant friar of Islam.

This extraordinary proceeding, far more bizarre in a youthful Mughal prince than in the elderly, gouty, and disappointed Emperor Charles V, has been set down by some of his critics to Aurangzib’s subtle calculation and hypocrisy. It is insinuated that the pretence of indifference to the seductions of power was designedly adopted with a view to hoodwink his contemporaries as to his real ambition. There is, however, no reasonable ground for the insinuation, which is but one of many instances of the way in which Aurangzib’s biographers have ridden to death their theory of his duplicity. So far from proving of service to him, his choice of a life of devotion only drew down his father’s severe wrath. The Prince was punished by the stopping of his pay, the loss of his rank and estates, and his deposition from the governorship of the Deccan. His own family were undoubtedly impressed with his religious character, and his eldest brother Mira, with the superior air of an

‘emancipated’ agnostic, called him ‘ that saint ‘; but it remains to be proved that they were deceived in their estimate of their brother, – a rare experience among close relations, – or that his accepted rôle as a devotee raised his character in the estimation of either the nobles or the people. Moreover, had he been so deeply designing an impostor, he would have played his part so long as was necessary to develop his plans; he would have waited till the opportunity came to strike, for which he was watching in his lonely cell. Instead of this, in a year’s time Aurangzib was out of his seclusion, exercising all the powers of a Viceroy in the important province of Gujarat. Henceforward we shall see him always to the fore when war was going on, keeping himself steadily before the eyes of the people. The truth seems to be that his temporary retirement from the world was the youthful impulse of a morbid nature excited by religious enthusiasm. The novelty of the experiment soon faded away; the fakir grew heartily tired of his retreat; and the young Prince returned to carry out his notions of asceticism in a sphere where they were more creditable to his self-denial, and more operative upon the great world in which he was born to work. He was not destined to be a

‘Deedless dreamer, lazying out a life

Of self-suppression:’

his ascetic mind was fated to influence the course of an empire.

The youthful dream was soon dispelled, and the

erewhile fakir became a statesman and a leader of armies. In February, 1647, Shah-Jahan raised him to the rank of a mansabdar of 15,000 personal and 10,000 horse, and ordered him to take command of the provinces of Balkh and Badakhshan, on the north-west side of the Hindu Kush, which had lately been added to the Mughal Empire. They had once been the dominion of Mbar, the grandfather of Akbar, and it had long been the ambition of Shah-Jahan to assert, his dormant claim and recover the territory of his renowned ancestor. He even aspired to use these provinces as stepping-stones to the recovery of the ancient kingdom of Samarkand, once the capital of a still earlier and more famous ancestor, Timur, the ‘Scourge of God.’ This kingdom, with the dependent provinces of Balkh and Badakhshan, now belonged to the Uzbegs, who were governed by a member of the Astrakhan dynasty, ultimately descended, like their Indian antagonists, from Jinghiz Kaan. Their sway, however, was but a shadow of the power which Tamerlane had bequeathed to his successors; and the Persian general Ali Mardan, accompanied by the youngest Imperial Prince, Murad-Bakhsh, at the head of 50,000 horse and 10,000 foot and artillery, had accomplished, though not without severe fighting, the conquest of Balkh and the neighbouring cities in 1645.

The difficulty, however, was not so much how to take, but how to keep, this distant region, separated by the snowy ranges of the Hindu Kush from the rest of the Empire, inaccessible in winter, and exposed at

all times to the attack of the indomitable hill tribes, who have always made the government of the mountain region a thankless task to every ruler who has attempted to subdue them. When Aurangzib reached the scene of his government, he soon perceived the character of the country and its defenders, and like a wise general counselled a retreat from an untenable position. He made terms with the King of the Uzbegs, restored the useless provinces, and began his march home. It was now October, and no time was to be lost in re-crossing the mountains. A long scene of disaster ensued, though Aurangzib, in concert with his Persian and Indian advisers, took every precaution, and personally superintended the movement. The hill men hovered about the flanks of the retreating Rajputs, cut off detached parties, and harassed every step. The baggage fell over precipices; the Hazaras bristled above the narrow defiles; the Hindu Kush was under snow, which fell for five days; and 5000 men, to say nothing of horses, elephants, camels, and other beasts of burden, died from cold and exposure. It was but a dejected frostbitten remnant of the army that reached Kabul; and Shah-Jahan’s precious scheme of aggrandizement had cost the exchequer more than two million pounds.

Aurangzib’s next employment was equally unsuccessful. Kandahar, which had belonged to the Shah of Persia, had been surrendered to the Mughals ten years before (1637) by its able and ambitious governor, Ali Mardan, who speedily wiped out his

treachery to the old master by distinguished services to the new, not only in war, but in such works of peace as the well-known canal at Delhi, which still bears his name. Towards the close of 1648 the Persians besieged the City, and Aurangzib and the great minister, Sa’d-Allah ’Allami, accompanied by Raja Jai Singh and his Rajputs, were sent to relieve it. The Mughal army numbered 60,000 horse and 10,000 infantry and artillery. Before they reached Kabul, however, Kandahar had fallen; and measures were accordingly taken for a siege. In May, 1649, the Mughals opened their batteries, and mines and countermines, sallies and assaults, went on with great vigour for four months. The army, however, had come for a pitched battle, not for a siege, and there were no heavy guns. By September little progress had been made, and the winter was coming on. Aurangzib had experienced one winter retreat in the mountains, and he would not risk a second. The army retired to Kabul.

In the spring of 1652, another attempt was made to recover Kandahar, and Aurangzib was again sent with Sa’d-Allah, at the head of an army ‘like the waves of the sea,’ with a siege-train, including eight heavy and twenty light guns, and 3000 camels carrying ammunition. But the frontiers were strong and vigorously defended; the besiegers’ guns were badly served, and two of them burst; the enemy’s sallies and steady fire drove back the engineers; and after two months and eight days the siege was again abandoned.

Nor was an even more determined leaguer by Prince Dara, early in the following year any more successful, though some of his ordnance projected shot of nearly a hundredweight.

These campaigns in Afghanistan and beyond the Hindu Kush are of no importance in the history of India, except as illustrating the extreme difficulty of holding the mountain provinces from a distant centre, whether it be Delhi or Calcutta; but they were of the greatest service to Aurangzib. They put him in touch with the imperial army, and enabled him to prove his courage and generalship in the eyes of the best soldiers in the land. It is not to be supposed that, with tried commanders like Ali Mardan, Jai Singh, and Sa’d-Allah, at his side, Aurangzib enjoyed the real command. He was doubtless at first more a nominal than an acting general, – a princely figure-head to decorate the war-ship of proved officers. But as time went on, opportunities occurred for the exercise of his personal courage and tactical skill. The generals learnt to appreciate him at his true value, and the men discovered that their Prince was as cool and steady a leader as the best officer in India. When they saw him, in the midst of a battle with the Uzbegs, at the hour of evening prayer, calmly dismounting and performing his religious rites under fire, they recognised the mettle of the man. Henceforth every soldier and statesman in Hindustan knew that, whatever time should bring forth in the future of the empire, Aurangzib was a factor to be reckoned with.

He had gone over the mountains an unknown quantity, a reputed devotee, with no military record to give him prestige. He came back an approved general, a man of tried courage and powers of endurance, a prince whose wisdom, coolness and resolution had been tested and acclaimed in three arduous campaigns. The wars over the north-west frontier had ended as such wars have often ended since, but they had done for Aurangzib what they did for Stewart and Roberts; they placed their leader in the front rank of Indian generals. After Balkh and Kandahar, the Prince was recognized as the coming man.

6. The translation of these names is Dara, King; Shuja, Valiant; Aurangzib, Throne-ornament; Murad-Bakhsh, Desire-attained. Shah-Jahan had altogether fourteen children, all by his wife Mumtaz Mahall, whom he married in 1612, and who died in 1631. Six were girls and eight boys. Seven of them died in infancy; the names of those who grew up are given in the annexed pedigree, where the princesses are printed in italics. The Princess Kudsiya was apparently also known as Gohar-Ara.

7. Bernier, Travels, translated by Arch. Constable (1891), pp. 7, 8. To this edition, published as vol. i. of ‘Constable’s Oriental Miscellany,’ all subsequent quotations from Bernier refer.

8. See below, p. 76.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()