Simple of life and ascetic as he was by disposition, Aurangzib could not altogether do away with the pomp and ceremony of a Court which had attained the pinnacle of splendour under his magnificent father33. In private life it was possible to observe the rigid rules, and practise the privations of a saint; but in public the Emperor must conform to the precedents set by his royal ancestors from the days of Akbar, and hold his state with all the imposing majesty which had been so dear to Shah-Jahan. Little as he was himself disposed to cultivate ‘ the pomps and vanities of this wicked world,’ he was perfectly aware of their importance in the eyes of his subjects. A Great Mogul, without gorgeous darbars, dazzling jewels, a glittering assemblage of armed and richly habited courtiers, and all the pageantry of royal state, would have been inconceivable, or contemptible,

to a people who had been accustomed for centuries to worship and delight in the glorious spectacle of august monarchs enthroned amid a blaze of splendour. With Orientals, more even than with Europeans, the clothes make the king; and not his own subjects only, but the ambassadors of foreign Powers would have thought meanly of the Emperor if he had wholly cast off the purple and fine linen of his rank and neglected to receive them sumptuously, as became a grand monargue. Accordingly Aurangzib followed, at least in his earlier years and in the more essential ceremonial details, the Court custom which had been handed down unchanged from the first organizer of the Empire, his great-grandfather Akbar.

The Emperor divided his residence between Delhi and Agra, but Delhi was the chief capital, where most of the state ceremonies took place. Delhi was the creation of the Mughals, for the old city of former kings had been dismantled and neglected to form the new capital of Shahjahanabad, ‘The City of Shah-Jahan,’ which that Emperor built in 1638-48, and, more Mongolico, named after himself. Agra had been the metropolis of Akbar, and usually of Jahangir; but its sultry climate interfered with the enjoyment of their luxurious successor, and the Court was accordingly removed, at least for a large part of the year, to New Delhi, the ‘City of Shah-Jahan.’ The ruins of this splendid capital, its mosques, and the noble remains of its superb palace are familiar to every reader. To see it as it was in its glory, however, we

must look through the eyes of Bernier, who saw it when only eleven years had passed since its completion. His description was written at the capital itself, in 1663, after he had spent four years of continuous residence there; so it may be assumed that he knew his Delhi thoroughly. The city, he tells us, was built in the form of a crescent on the right bank of the Jamna, which formed its north-eastern boundary, and was crossed by a single bridge of boats. The flat surrounding country was then, as now, richly wooded and cultivated, and the city was famous for its luxuriant gardens. Its circuit, save on the river side, was bounded by brick walls, without moat or fosse, and of little value for the purpose of defence, since they were scarcely fortified, save by some flanking towers of antique shape at intervals of about one hundred paces, and a bank of earth forming a platform behind the walls, four or five feet in thickness.’ The circuit of the walls was six or seven miles; but outside the gates were extensive suburbs, where the chief nobles and wealthy merchants had their luxurious houses; and there also were the decayed and straggling remains of the older city just without the walls of its supplanter. Numberless narrow streets intersected this wide area, and displayed every variety of building, from the thatched mud and bamboo huts of the troopers and camp-followers, and the clay or brick houses of the smaller officials and merchants, to the spacious mansions of the chief nobles, with their courtyards and gardens, fountains and cool matted

chambers, open to the four winds, where the afternoon siesta might be enjoyed during the heats.

Two main streets, perhaps thirty paces wide, and very long and straight, lined with covered arcades of shops, led into the ‘great royal square ‘ which fronted the fortress or palace of the Emperor. This square was the meeting-place of the citizens and the army, and the scene of varied spectacles. Here the Rajput Rajas pitched their tents when it was their duty to mount guard; for Rajputs never consented to be cooped up within Mughal walls. Here might be seen the cavalcade of’ the great nobles when their turn to watch arrived.

Nothing can be conceived much more brilliant than the great square in front of the fortress at the hours when the Omrahs, Rajas, and Mansabdars repair to the citadel to mount guard or attend the assembly of the Am-Khas [or Hall of Audience). The Mansabdars flock thither from all parts, well mounted and equipped, and splendidly accompanied by four servants, two behind and two before, to clear the street for their roasters. Omrahs and Rajas ride thither, some on horseback, some on majestic elephants; but the greater part are conveyed on the shoulders of six men, in rich palankins, leaning against a thick cushion of brocade, and chewing their betel, for the double purpose of sweetening their breath and reddening their lips. On the one side of every palankin is seen a servant bearing the pikdan, or spittoon of porcelain or silver; on the other side two more servants fan the luxurious lord, and flap away the flies, or brush off the dust with a peacock’s-tail fan; three or four footmen march in front to clear the way, and a chosen number of the best formed and best mounted horsemen follow in the rear.

‘Here too is held a bazar or market for an endless variety of things; which, like the Pont Neuf at Paris, is the rendezvous for all sorts of mountebanks and jugglers. Hither likewise the astrologers resort, both Muhammadan and Gentile [Hindu]. These wise doctors remain seated in the sun, on a dusty piece of carpet, handling some old mathematical instruments, and having open before them a large book which represents the signs of the zodiac. ... They tell a poor person his fortune for a paisa (which is worth about one sol); and after examining the hand and face of the applicant, turning over the leaves of the large book, and pretending to make certain calculations, these impostors decide upon the seat or propitious moment of commencing the business he may have in hand.’

Among the rest a half-caste Portuguese from Goa sat gravely on his carpet, with an old mariner’s compass and a couple of breviaries for stock in trade: he could not read them, it is true, but the pictures in them answered the turn, and he told fortunes as well as the best. A tal Bestias, tal Astrologuo, he unblushingly observed to the Jesuit Father Buzée, who saw him at his work. Nothing was done in India in those days without consulting astrologers, of whom these bazar humbugs were the lowest rank. Kings and nobles granted large salaries to these crafty diviners, and never undertook the smallest affair without taking their advice. ‘They read whatever is written in heaven; fix upon the sa’at, and solve any doubt by opening the Koran.’

Beyond the ‘great royal square’ was the fortress, which contained the Emperor’s palace and mahall or

seraglio, and commanded a view of the river across the sandy tract where the elephant fights took place and the Raja’s troops paraded. The lofty walls were slightly fortified with battlements and towers and surrounded by a moat, and small field pieces were pointed upon the town from the embrasures. The palace within was the most magnificent building of its kind in the East, and the private rooms or mahall alone covered more than twice the space of the Escurial or of any European palace. One entered the fort between two gigantic stone elephants carrying the statues of Rajas Jai Mal and Patta of Chitor, who offered a determined resistance to Akbar, and, sooner than submit, died in a last desperate sally; so that their memory was cherished even by their enemies. Passing between these stone heroes ‘with indescribable awe and respect,’ and crossing the courtyard within, the long and spacious Silver Street stretched before one, with its canal running down the middle, and its raised pavements and arcades on either side. Other streets opened in every direction, and here and there were seen the merchants’ caravanserais and the great workshops where the artisans employed by the Emperor and the nobles plied their hereditary crafts of embroidery, silver and gold smithery, gun-making, lacquer-work, muslin, painting, turning, and so forth.

Delhi was famous for its skill in the arts and crafts. It was only under royal or aristocratic patronage that the artist flourished; elsewhere the artisan was at the mercy of his temporary employer, who paid him

as he chose. The Mughal Emperors displayed a laudable appreciation of the fine arts, which they employed with lavish hands in the decoration of their palaces.

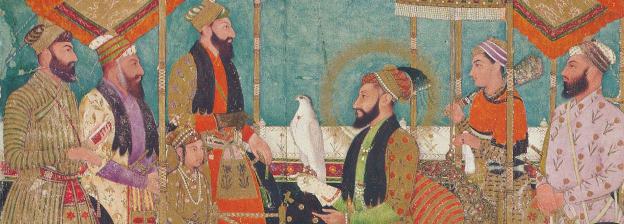

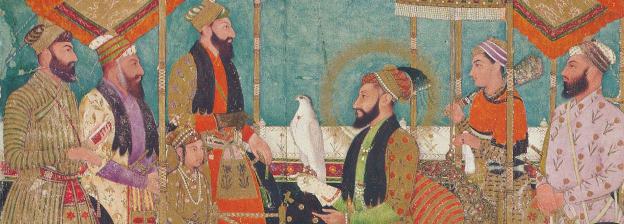

‘The arts in the Indies,’ says Bernier, would long ago have lost their beauty and delicacy, if the Monarch and principal Omrahs did not keep in their pay a number of artists who work in their houses.’ Yet there are ingenious men in every part of the Indies. Numerous are the instances of handsome pieces of workmanship made by persons destitute of tools, and who can scarcely be said to have received instruction from a master. Sometimes they imitate [alas!] so perfectly articles of European manufacture, that the difference between the original and the copy could hardly be discerned. Among other things the Indians make excellent muskets and fowling-pieces, and such beautiful gold ornaments that it may be doubted if the exquisite workmanship of those articles can be exceeded by any European goldsmith. I have often admired the beauty, softness, and delicacy of their paintings and miniatures, and was particularly struck with the exploits of Akbar, painted on a shield, by a celebrated artist, who is said to have been seven years in completing the picture. The Indian painters are chiefly deficient in just proportions, and in the expression of the face.’

The orthodox Muhammadan objection to the representation of living things had been overruled by Akbar, who is recorded to have expressed his views on painting in these words:–

‘There are many that hate painting; but such men I dislike. It appears to me as if a painter had quite peculiar means of recognizing God. For a painter in sketching anything that has life, and in devising its limbs one after the other,

must come to feel that he cannot bestow individuality upon his work, and is thus forced to think of God, the giver of life, and will thus increase in knowledge.’

A large number of exquisite miniatures, or paintings on paper designed to illustrate manuscripts, or to form royal portrait-albums, have come down to us from the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries, which fully bear out Bernier’s praise. The technique and detail are admirable, and the colouring and lights often astonishingly skilful. They include portraits of the emperors, princes, and chief nobles, which, in spite of Bernier’s criticism, display unusual power in the delineation of individual countenances; and there are landscapes which are happily conceived and brilliantly executed34. There is no doubt that the Jesuit missions at Agra and other cities of Hindustan brought western ideas to bear upon the development of Indian painting. Jahangir, who was, by his own account, very fond of pictures and an excellent judge of them,’ is recorded to have had a picture of the Madonna behind

a curtain, and this picture is represented in a contemporary painting which has fortunately been preserved35. Tavernier saw on a gate outside Agra a representation of Jahangir’s tomb ‘carved with a great black pall with many torches of white wax, and two Jesuit Fathers at the end,’ and adds that Shah-Jahan allowed this to remain because ‘his father and himself had learnt from the Jesuits some principles of mathematics and astrology36.’ The Augustinian friar Manrique, who came to inspect the Jesuit missions, in the time of Shah-Jahan, found the Prime-minister Asaf Khan, at Lahore, in a palace decorated with pictures of Christian saints37. In most Mughal portraits, the head of the Emperor is surrounded by an aureole or nimbus, and many other features in the schools of painting at Agra and Delhi remind one of contemporary Italian art. The artists were held in high favour at Court, and many of their names have been preserved. Their works added notably to the decoration of the splendid and elaborate palaces which are amongst the most durable memorials of the Mughal period.

Leaving the artists’ workshops, and traversing the guard’s quadrangle, one reached the cynosure of all courtiers’ eyes, the Hall of Audience, or Am-Khas; a vast court, surrounded by covered arcades, with a great open hall or sublimated portico, raised above

the ground, on the further side, opposite the great gate. The roof of this hall was supported by rows of columns, and beautifully painted and gilt, and in the wall which formed its back was, and still is, the famous jharukha, – the ample open window where the Great Mogul daily sat upon his throne to be seen of all the people who thronged the spacious court. On his right and left stood the Princes of the Blood; and beneath, in the hall itself, within a silver railing, were grouped the four Secretaries of State, and the chief nobles and officers of the realm, the Rajas, and the many ambassadors who came from foreign States, all standing with eyes cast to the ground and hands crossed in the customary attitude of respect, while the King’s musicians discoursed ‘sweet and pleasant music.’ Further off; and lower down, outside the silver rail, the array of Mansabdars and lesser nobles and officials gleamed with colour and jewels and steel, while the rest of the hall and the whole court were thronged with every class of the subjects, high and low, rich and poor, all of whom had the right to see and have audience of the Emperor. Once there, however, no one might leave the Presence until the levee was over.

The scene on any State occasion was imposing, and almost justified the inscription on the gateway: ‘If there be a Heaven upon earth, it is Here, it is Here.’ The approach of Aurangzib was heralded by the shrill piping of the hautboys and clashing of cymbals from the band-gallery over the great gate:–

‘The King appeared seated upon his throne at the end of the great hall in the most magnificent attire. His vest was of white and delicately flowered satin, with a silk and gold embroidery of the finest texture. The turban of gold cloth had an aigrette whose base was composed of diamonds of an extraordinary size and value, besides an oriental topaz which may be pronounced unparalleled, exhibiting a lustre like the sun. A necklace of immense pearls suspended from his neck reached to the stomach. The throne was supported by six massy feet, said to be of solid gold, sprinkled over with rubies, emeralds, and diamonds. It was constructed by Shah-Jahan for the purpose of displaying the immense quantity of precious stones accumulated successively in the Treasury from the spoils of ancient Rajas and Patans, and the annual presents to the monarch which every Omrah is bound to make on certain festivals38. At the foot of the throne were assembled all the Omrahs, in splendid apparel, upon a platform surrounded by a silver railing and covered by a spacious canopy of brocade with deep fringes of gold. The pillars of the ball were hung with brocades of a gold ground, and flowered satin canopies were raised over the whole expanse of the extensive apartment, fastened with red silken

cords from which were suspended large tassels of silk and gold. The floor was covered entirely with carpets of the richest silk, of immense length and breadth. A tent, called the aspek, was pitched outside [in the court], larger than the hall, to which it joined by the top. It spread over half the court, and was completely enclosed by a great balustrade, covered with plates of silver. Its supporters were pillars over-laid with silver, three of which were as thick and as high as the mast of a barque, the others smaller. The outside of this magnificent tent was red, and the inside lined with elegant Masulipatan chintzes, figured expressly for that very purpose with flowers so natural and colours so vivid that the tent seemed to be encompassed with real parterres.

As to the arcade galleries round the court, every Omrala had received orders to decorate one of them at his own expense, and there appeared a spirit of emulation who should best acquit himself to the Monarch’s satisfaction. Consequently all the arcades and galleries were covered from top to bottom with brocade, and the pavement with rich carpets.’

The scene described so minutely by Bernier was exceptionally brilliant, and the reason assigned for the unusual splendour and extravagance of the decorations was Aurangzib’s benevolent desire to afford the merchants an opportunity for disposing of the large stock of brocades and satins which had been ac-cumulating in their warehouses during the unprofitable years of the war of succession. But festivals of similar though less magnificence were held every year, on certain anniversaries, of which the chief was the Emperor’s birthday, when, in accordance with time-honoured precedent, he was solemnly weighed

in a pair of gold scales against precious metals and stones and food, all which was ostensibly to be distributed to the poor on the following day; and when the nobles one and all came forward with handsome birthday presents of jewels and golden vessels and coins, sometimes amounting altogether to the value of £2,000,000. On these occasions the fairest ladies of the chief nobles sometimes held a sort of fancy bazar in the imperial seraglio, where they sold turbans worked on cloth of gold, brocades, and embroideries to the Emperor and his wives and princesses at exorbitant prices, governed chiefly by the wit and beauty of the seller. A vast deal of good-humoured banter and haggling went on over these bargainings, and many a young lady made a reputation which served her in good stead when it came to the question of marrying her to a Court favourite. Of course no man but the Emperor was allowed to see these unveiled beauties, but the Mughal and his Begams were excellent match-makers, and could be trusted to do the best for the debutantes. The festivals generally ended with an elephant-fight, which was as popular in India as a bull-fight in Spain. Two elephants charged each other over an earth wall, which they soon demolished; their skulls met with a tremendous shock, and tusks and trunks were vigorously plied, till at length one was overcome by the other, when the victor was separated from his prostrate adversary by an explosion of fireworks between them. The chief sufferers were the mahouts

or riders, who were frequently trodden under foot and killed on the spot; insomuch that they always took formal leave of their families before mounting for the hazardous encounter. In spite of their growing effeminacy, there was enough of the old savage Mughal blood in Aurangzib’s courtiers to make them delight in these dangerous and cruel exhibitions. Indeed, most of the spectacles that enlivened the Court were of a warlike character; and luxurious as were their habits, the petticoated Mughals could still be roused to valour, while no nation produced keener sportsmen.

In the jovial days of Jahangir and Shah-Jahan, the blooming Kenchens or Nautch girls used to play a prominent part in the Court festivities, and would keep the jolly emperors awake half the night with their voluptuous dances and agile antics. But Aurangzib was ‘unco gude’ and would as soon tolerate idolatry as a Nautch. He did his best to suppress music and dancing altogether, in accordance with the example of the Blessed Prophet, who was born without an ear for music and therefore hastily ascribed the invention of harmony to the Devil. The musicians of India were certainly noted for a manner of life which ill accorded with Aurangzib’s strict ideas, and their concerts were not celebrated for sobriety. The Emperor determined to destroy them, and a severe edict was issued. Raids of the police dissipated their harmonious meetings, and the instruments were burnt. One Friday, as

Aurangzib was going to the mosque, he saw an immense crowd of singers following a bier, and rending the air with their cries and lamentations. They seemed to be burying some great prince. The Emperor sent to inquire the cause of the demonstration, and was told it was the funeral of Music, slain by his orders, and wept by her children. I approve their piety,’ said Aurangzib gravely let her be buried deep, and never be heard again39.’ Of course the concerts went on in the palaces of the nobles, but they were never heard at Court. The Emperor seriously endeavoured to convince the musicians of the error of their ways, and those who reformed were honoured with pensions.

Even on every day occasions, when there were no festivals in progress, the Hall of Audience presented an animated appearance. Not a day passed, but the Emperor held his levee from the jharukha window, whilst the bevy of nobles stood beneath, and the common crowd surged in the court to lay their grievances and suits before the imperial judge. The ordinary levee lasted a couple of hours, and during this time the royal stud was brought from the stables opening out of the court, and passed in review before the Emperor, so many each day; and the household elephants, washed and painted black, with two red streaks on their foreheads, came in their embroidered caparisons and silver chains and bells, to be inspected

by their master, and at the prick and voice of their riders saluted the Emperor with their trunks and trumpeted their taslim or homage. Hounds and hawks, hunting leopards, rhinoceroses, buffaloes, and fighting antelopes were brought forward in their turn; swords were tested on dead sheep; and the nobles’ troops were paraded.

‘But all these things are so many interludes to more serious matters. The King not only reviews his cavalry with particular attention, but there is not, since the war has been ended,*a single trooper or other soldier whom he has not inspected and made himself personally acquainted with, increasing or reducing the pay of some, and dismissing others from the service. All the petitions held up in the crowd assembled in the Am-Khas are brought to the King and read in his hearing; and the persons concerned being ordered to approach are examined by the Monarch himself, who often redresses on the spot the wrongs of the aggrieved party. On another day of the week he devotes two hours to hear in private the petitions of ten persons selected from the lower orders, and presented to the King by a good and rich old man. Nor does he fail to attend the justice chamber on another day of the week, attended by the two principal Kazis or chief justices. It is evident, therefore, that barbarous as we are apt to consider the sovereigns of Asia, they are not always unmindful of the justice that is due to their subjects40.’

The levee in the beautiful Audience Hall was not the Emperor’s only reception in the day. In the evening he required the presence of every noble in the Ghuzl-Khana, a smaller and more private hall behind

the Am-Khas, but no less beautifully decorated. Here he would sit, surrounded by his Court, and ‘grant private audiences to his officers, receive their reports, and deliberate on important matters of state.’ This later reception was almost as ceremonious as the earlier one, but there was no space for reviews of cavalry: only the officers who had the honour to form the guard paraded before the Emperor, preceded by the insignia of royalty, the silver fish, dragon, lion, hands, and scales, emblematic of the various functions of sovereignty.

Close to the Hall of Audience was the imperial mosque, with its gilded dome, where Aurangzib daily conducted the prayers. On Fridays he went in state to the Jami Masjid, the beautiful mosque which Shah-Jahan completed just before his deposition. It stands on a rocky platform in the centre of Delhi, in a great square where four streets meet. The roads were watered before the procession passed, and soldiers kept the way. An advance guard of cavalry announced the approach of Aurangzib, and presently the Emperor appeared, riding beneath a canopy on a richly caparisoned elephant, or seated upon a dazzling throne borne by eight men upon a gorgeous litter, while the nobles and officers of the Court and mace-bearers followed on horseback or in palankins.

‘If we take a review,’ concludes Bernier, of ‘this metropolis of the Indies, and observe its vast extent and its numberless shops; if we recollect that, besides the Omrahs,

the city never contains less than 35,000 troopers, nearly all of whom have wives, children, and a great number of servants, who, as well as their masters, reside in separate houses; that there is no house, by whomsoever inhabited, which does not swarm with women and children; that during the hours when the abatement of the heat permits the inhabitants to walk abroad, the streets are crowded with people, although many of those streets are very wide, and, excepting a few carts, unencumbered with wheel carriages; we shall hesitate before we give a positive opinion in regard to the comparative population of Paris and Delhi; and I conclude, that if the number of souls be not as large in the latter city as in our own capital, it cannot be greatly less.’

33. The prime authority on Aurangzib’s Court at Delhi is Bernier’s Travels. His admirable description, full of the graphic power of an observant eye-witness, has been excellently rendered by Mr. Archibald Constable in his translation Constable’s Oriental Miscellany, vol. i. 1891), which I have been permitted to quote.

34. Mr. Archibald Constable has brought two of these interesting relics of a little-known art within the reach of all by reproducing them with marked success in his Oriental Miscellany, where the frontispiece to Bernier’s Travels is a fine portrait of Shah-Jahan, and a landscape of Akbar hunting by night illustrates Somervile’s Chace, appended to Dryden’s Aureng-Zebe. Both are after originals in Colonel B. Hanna’s collection. The portrait of Aurangzib prefixed to this volume is after a drawing by an Indian artist, contained in an album in the British Museum (Add. 18,801, no. 34): which bears the seal of Ashraf Khan and the date A.H. 1072 (1661, 2). It represents Aurangzib at about the time of his accession, or perhaps somewhat earlier, and belongs to the rarest and finest class of Indian portraits.

35. In the collection of Colonel H. B. Hanna.

36. Travels, vol. i. p. III.

37. Manrique. Itinerario (1649)/ 374.

38. Tavernier (i. 381–5) has recorded an elaborate description of the famous Peacock Throne, which resembled, he says, a bed, standing upon four (not six) massive feet, about two feet high, and was covered by a canopy supported by twelve columns, belted with fine pearls, from which hung the royal sword, mace, shield, bow and arrows. The throne was plated with gold and inlaid with diamonds, emeralds, pearls, and rubies. Above the canopy was a golden peacock with spread tail, composed of sapphires and other stones. On either side of the peacock were bouquets of golden flowers inlaid with precious stones; and in front were the parasols of state, fringed with pearls, which none but the Emperor was permitted to use. The throne is now preserved in the Shah’s palace at Tehran, and is valued at about .£2,600,000. Bernier and Tavernier priced it much higher.

39. Khafi Khan, in Elliot and Dowson, vol. vii. pp. 283-4; Catrou, Histoire générale de l’Empire du Mogol, Troisième Partie p. 5.

40. Bernier, p. 263.

This collection transcribed by Chris Gage![]()