Though beautiful, tiny flowers of youngia open only a few hours in the morning and produce copious seed to infest nearby ground. Photo by Johnny Randall

Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

Well now, I had a wonderful, easy-to-grow, native wildflower groundcover all lined up for this week’s Flora when an awful, innocent-looking plant alien pushed it aside.

It’s most important that you know about this plant bully, Youngia japonica, called youngia or Asiatic hawk’s beard.

It is an annual with a leafy rosette that looks a bit like the common dandelion, but the leaves are a pale yellow green and a bit hairy. Learn to recognize it, pull it up and throw into the trash. Don’t dare put it in your compost pile or toss it aside to die. Though it is an annual, it has quite a taproot, so dare not turn your back on this little monster unless you are certain you have extracted the whole plant, root and all! It may continue to set seed even after being pulled from the ground.

A relative newcomer in terms of exotic invasives, it was first brought to my attention a little more than a decade ago by horticulturist Sally Heiney at the N.C. Botanical Garden. She called it to the attention of all the staff as soon as it began showing up along the garden edges. Sally dutifully warned that if it were not immediately and completely destroyed, it would show up the next season by the hundreds.

I learned the hard way. I did not bother with the single plant I noticed in my yard several years ago, and the following spring the yard was literally covered with youngia, as Sally had warned. So I spent an hour or two extracting every plant and have kept careful watch every since and only now and then do I notice one or two here and there.

Take another good hard look at that basal rosette of yellowish-green leaves. Like the staff at the botanical garden, I have learned to recognize it by sight and pounce on every one I see. It literally is running rampant across gardens and pathways in Carrboro and Chapel Hill and even along some of the edges of the well-manicured plantings on the UNC campus.

How amazed I was two weeks ago while viewing the spectacular Dutchman’s breeches display along the Flat River north of Durham; several of us spotted a single rosette of this plant hunkered down amongst all those native beauties. You really do learn to spot it. We pounced on it in unison and brought it out with us. We kept a watchful eye out for more and were happy to find none.

Those tiny airborne seeds, typical of the aster family, fly far and wide, so no area is safe. We felt honorable that at least we had kept dozens, perhaps hundreds, of new plants from invading that lovely spot next year.

I know of no other exotic that has become so invasive in so short a period. So please do your part. Study the images and keep a watchful eye, and don’t leave a one to survive.

Thanks for paying attention, and next week I promise a happier story!

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

It was the first weekend in April last year that I thought I’d died and gone to heaven when chancing upon carpets of the tiny little red-eyed, purple-petaled bluets carpeting the sacred ground of the Sparrow Cemetery out on Mt. Carmel Church Road.

Not to be confused with the common bluet, also called Quaker Ladies, Houstonia caerulea, this red-eyed little gem of a flower is called the tiny bluet, Houstonia pusilla.

I made a mental note to return this year to see the hundreds upon hundreds of tiny bluets spreading across that quiet, revered landscape. Two weeks ago I checked to see if they had begun to appear.

Since everything seems to be several weeks ahead this spring, I was not surprised to find them already cheerfully in flower. They were not, however, at peak, so you can still see them.

If you explore the higher ground of the cemetery you will discover that you must step carefully to avoid crushing them.

If the sunlight is angled just perfectly, you may see them as pale-purple carpets across the open grassy surface. The flowers are so small (1/8-inch across) that you’ll have to drop to your knees to get a closer look at the intense blood-red eye.

Tiny bluets are annuals that move around the landscape, seeking openings in yards in early spring before the grasses grow tall enough to shade them.

Most folks are familiar with the pale-blue bluet, the Quaker Ladies, also called the common bluet, which is two to three times larger than its tiny cousin. The common bluet is distinguished by its yellow eye. It is a perennial and is most frequently spied along bare woodland trails and scattered on mossy banks. If you maintain a moss garden by keeping fallen leaves raked away during fall and winter, you most likely have the pale-blue, almost white Quaker Ladies happily holding court on your moss carpet right now. They return year after year on mossy grounds.

I don’t recall seeing these two different bluets growing together, and I’m wondering if they may have different soil preferences. The mossy carpets holding Quaker Ladies occur on naturally acidic ground, while the tiny bluets appear more commonly with grasses in yards that are not very acidic. I’ll have to keep thinking about that.

Another good spot to find tiny bluets is along the old farm road bisecting the second set of fields at Mason Farm Biological Reserve. A little farther along you’ll find Quaker Ladies, by themselves, scattered along shady edges.

While you’re out practicing close-to-the-ground “belly botany,†keep an eye out for the little wild field pansy, Viola bicolor, that varies in color from white to purple, with dark stripes and a yellow center. Sometimes they are numerous enough to appear as carpets of color on the ground, and lying on such a carpet is another died-and-gone-to-heaven kind of experience.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

Tread gently among the trout lilies

By Ken Moore

Flora columnist

More than four weeks ago Dave Otto spotted a trout lily in flower on Bolin Creek. Since then I have seen what I would describe as “peak†trout lily flowering along many woodland trails. Normally “peak†flowering lasts only a week or so, and two weeks ago, during my final winter flora field trip, I called attention to lily seed capsules already ripening and slumping to the ground. Soon those capsules will split open, and eager ants will collect and bury the seed in their underground condominiums.

Trout lilies "as far as the eye can see" still on Bolin Creek slope. Photo by Brian Stokes

So last week while surveying the Adams Tract tree identification markers, I was pleasantly surprised on my descent down to Bolin Creek. The northern slopes of the Adams Tract were sheer carpets of trout lilies in “peak†flowering, as far as the eye could see.

One has to marvel at nature’s wisdom, not allowing this tiny woodland lily to put all its eggs in one basket, so to speak. Flowers appear early at some locations (think of micro environmental niches like sun exposure and cool air pockets) and later at other locations.

And, as is certainly the case along Bolin Creek, plants at any particular site do not flower all at once. Though most of the population may flower in unison, there are always a few that pop up early and a few that linger past the prime of the others. They are spreading their opportunities for success over the entire short six- to eight-week seasonal appearance above ground. Such strategic wisdom is characteristic throughout nature’s diverse populations of flora and fauna.

Fresh foot traffic leaves trout lily bulb to wither above bare ground. Photo by Ken Moore

While it was wonderful to view carpets of lilies, mosses, ferns, grasses and other flowers on the steep slopes above the creek, it was terrible to observe several long patches of bare ground where bunches of mosses and even the bulbs of trout lilies were left exposed to wither along the edges.

The Town of Carrboro was not given additional resources when handed the extra responsibilities of erosion control and trail maintenance of the Adams Tract, so it is especially bothersome that residents don’t support their efforts to manage the trails and protect the slopes. As dog walkers frequently don’t keep their pets leashed as requested by town signage, neither do walkers, runners and bikers keep to town-designated trails during their visits. Visitors who choose to step over barriers to closed trails or make their own short cuts contribute to erosion and degradation of the wildflower slopes.

Additional deterioration of the vegetation on the slopes results from unsupervised children who naturally like to climb and scramble over rocks and up and down steep slopes. The mossy wildflower slopes of Bolin Creek are not an appropriate playground.

Thoughtless foot traffic destroys wildflower habitat on Bolin Creek slopes. Photo by Ken Moore

Perhaps Friends of Bolin Creek, who partnered with the town for the grant providing funds for the tree labels years ago, and the neighbors who cherish the corridor may combine their energies to educate visitors to treat the area with more respect. Those slopes have no defense against our footsteps.

Please do walk the trails often during this season to make your own discoveries, taking care that your footsteps are gentle ones, and gently educate others to follow your example.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

Male pollen-bearing, cone-like structures are now visible on red cedars. Photo by Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

This is the time in our changing seasons when we might become alarmed that some of our red cedar trees are diseased or otherwise sickly. And no wonder, as we observe many of the common red cedars, Juniperus virginiana, covered with what appears to be some kind of reddish-colored fungus or outright dead foliage.

Take a sigh of relief in knowing these reddish specimens are merely the male plants in full spring-flowering mode. You see, like holly trees, the cedars come to us as separate male and female plants. What we are seeing now, appearing like reddish foliage, is the bursting forth of countless tiny, male pollen-bearing, cone-like structures. They are so plentiful on some trees that they cover the entire leafy surface. Many of the ones I’ve observed closely during the past week have already dispersed their clouds of fine pollen and, amazingly, those little empty cones still cling to the trees following recent torrential rains.

In contrast, the female trees, some of them still bearing mature bluish juniper berries, retain a healthy green appearance. Even with a hand lens, the miniscule female flowers, waiting for windborne pollen from the males, are barely discernible. Once pollinated those tiny flowers, lacking petals, develop green berries that slowly mature to become visible in the fall.

Female flowers are barely discernible on red cedar. Photo by Ken Moore

A little later in the spring, another alarming-looking phenomenon, cedar apple rust, appears on the cedars. During wet, warmish days, some of the cedars bearing 1- to 2-inch round, hardened galls, become ornamented with bizarre bright-orange, jelly-like horns, which produce spores that infect nearby apple trees. In return, the apple tree responds with fungal spores that re-infect the red cedar to produce new galls. Cedar trees are not harmed, but the apple tree is often defoliated and the fruit rendered worthless.

Folks with apple trees, especially those with apple orchids, strive to eliminate cedar trees from apple tree proximity to insure tasty, good-looking apples.

Otherwise, common red cedar is very valuable. Not only is it a fine native tree that can thrive on bare dry soils, but it is valuable as a commercial wood, with old-timey cedar chests and long-lasting fence posts coming quickly to mind. Cedar chips for alternative indoor moth protection are a weekly commodity at the Carrboro Farmers’ Market, and many Native American-style flutes are made of cedar wood.

In addition, the evergreen habit provides important shelter and nesting for birds, and the berries are valuable nourishment for many animal species. It is the single host tree for the lovely Juniper Hairstreak butterfly.

Red cedar is sacred in Native-American culture. Cherokees only burned the wood on ceremonial occasions, believing the smoke expelled evil spirits. Medicinal uses of all parts of the tree for all types of ailments are well documented.

Male flowering red cedar (left) looks diseased next to a female tree (right). Photo by Ken Moore

It is hard to resist passing a cedar tree without smelling the scale-like leaves and tasting a berry or two. And it’s comforting to know the dramatic spring appearances are normal in nature’s seasonal cycles.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora (carrborocitizen.com/flora).

By Ken Moore

Flora columnist

Spring has sprung!

Three weeks ago local woods walker and photographer Dave Otto shared his image of trout lily, Erythronium umbilicatum, flowering down along Bolin Creek. Now trout lilies are carpeting forest floors everywhere. This is unusually early. That same week Dave found blue-flowered Hepatica americana, another early spring ephemeral.

This past weekend windflowers and spring beauties were also seen carpeting forest floors, and the painted buckeyes were already showing their flower buds tucked down inside emerging finger-like compound leaves. Those slowly emerging buds seem to be aware that frosty nights are not over.

Unlike the exotic flowering winter annuals like henbits and speedwells, covering yards since January and continuing for quite a while, these harbinger-of-spring native ephemerals will have flowered, set fruit and, in the case of the trout lily, be out of sight, dormant, in a couple of weeks.

They are called spring ephemerals because they emerge in chilly late winter to flower, fruit, disperse seed and return to dormancy in a fleetingly brief period, taking advantage of sunlight before deep shade from the leafy canopy returns the second week of April. So make haste to get outdoors now if you want to see them.

So how does this relate to André Michaux? It just so happens that the renowned French botanist observed these same seasonal wonders more than 200 years ago, and our state is saturated with the heritage of his travels.

Sometimes accompanied by his son François André, Michaux made nine botanical explorations crisscrossing eastern North America from Canada to Florida and the Bahamas during the period of 1787-96. Much of that exploration included the Carolina wilderness; travel was treacherous and encounters with Native Americans and Europeans alike were sometimes nearly fatal.

Officially searching the new world for worthy trees and plants to replenish the devastated forests of France, Michaux established two centers of operation with gardens and nurseries in New Jersey and Charleston for propagating and cultivating American plants to be sent for testing and cultivation in France.

This beautifully illustrated sassafras from Michaux's The North American Sylva is accompanied with detailed description of its natural distribution, medicinal and culinary merits and recommendations for cultivation. Photo of original source by Ken Moore

His botanical collections and notes are legendary. He is credited with observing and identifying 26 genera and 283 species of plants native to the Carolinas.

Wildflowers, like mountain spring beauty Claytonia carolinina, were named by him, and our official state wildflower, the Carolina lily, Lilium michauxii, is one of many plants named in honor of him.

Various editions of Michaux’s The North American Sylva, describing 156 species of native trees, illustrated by paintings of the team of Pierre J. Redoute, his brother Henri-Joseph and colleague Pancrae Bessa, are botanical treasures in rare book collections.

André Michaux will be visiting our region next week!

Michaux is brought to life by Michaux scholar, retired librarian Charlie Williams, who, in original French garb and accent, will describe some of Michaux’s travels, ordeals and discoveries.

This special event at the N.C. Botanical Garden on March 7 at 7 p.m. is a fundraiser for the UNC Herbarium, a unit of the Botanical Garden. There is a modest fee and pre-registration is required (962-0522).

A special presentation before André’s arrival by Garden Director Peter White will describe early American botanists, including legendary William Bartram of Philadelphia.

Spring has sprung and André Michaux will be here to celebrate with us!

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

Way over there in the watercress patch

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

Last week down in Saxapahaw during the 30th anniversary celebration of the Haw River Assembly, local musician and songwriter Tim Stambaugh excitedly said to me, “It’s watercress time again.†Tim, an enthusiastic explorer of our local nature, has been an annual visitor to a watercress patch in Battle Forest in the center of Chapel Hill.

Watercress, Nasturtium officinale, requires clear running water, something unusual these days. Though watercress is fairly common in parts of Virginia and north, it is only occasionally encountered throughout our state. I’ve seen it in the wild very few times.

Hearing about that watercress patch hidden away at the bottom of one of those Battle Forest slopes set me off searching for it with walking buddies Brian and Tony.

What a treasure to have nearby the 93-acre Battle Park with trails managed by the N.C. Botanical Garden as part of UNC. The forest of Battle Park is further extended via the Chapel Hill Greenway Battle Branch Trail connecting it to the Community Center on Estes Drive. That’s the easiest parking access to the park during weekdays, and that’s where we began our search.

It’s a 10-15 minute easy walk from there through impressive thickets of invasive exotics to arrive at one of the Garden’s helpful information kiosks where Copperhead Curve Trail crosses Battle Branch Creek.

Other entry-point interpretive kiosks are located at the Forest Theater, at the intersection of Gimghoul Road and Glandon Drive and along Park Place.

With interpretive guide and map in hand, it’s easy to marvel at the history and legend of specific points of interest throughout the forest. Having never been clear-cut, the forest contains monarch oaks, tulip poplars and American beech dating back to European settlement in 1740.

Not far from one of the dense areas of invading privet, honeysuckle and even red-berried nandina, we three were ecstatic to find that patch of emerald-green watercress.

Watercress, a perennial in the mustard family, is dependent on having its succulent stems and roots in the moving water. The watercress was nestled down in a stream close to where moving water magically emerged from beneath one of those giant trees.

We enjoyed tasting some of the tender new leaves, being careful not to disturb the base of the plants that seemed barely anchored in the streambed. The taste is distinctively spicy, unlike anything else.

My medicinal and edible-plant guru, Dr. James Duke, describes enjoying watercress up in Maryland almost all year long. He does lament, however, the reality of pollution in most streams and thus cautions about eating watercress without first cooking it. Though its spicy uncooked flavor is hard to beat, a few nights ago I really enjoyed the sweet taste of quickly sautéed watercress.

I am happy we found the watercress. Chapel Hillian Diana Steele reports knowing about that “down-in-the-woods†watercress as a youngster some years ago. Since that patch has been there for a while, I’m most proud that we three woods-walkers pulled out all the invasive Chinese privet from where, poised along streamside, it would eventually have displaced that watercress. In addition, we lingered long enough to extract a few of those encroaching nandinas.

You’ll find watercress easy to discover on Saturday mornings at the Carrboro Farmers’ Market, where at least one of the local farmers has it for observant patrons!

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

National Invasive Species Awareness Week is Feb. 26-March 3! Events are scheduled throughout the week in our nation’s capital (nisaw.org), and in North Carolina, the annual meeting of the North Carolina Exotic Pest Plant Council, open to the public, is Feb. 23-24 at the North Carolina Arboretum in Asheville (nceppc.weebly.com).

Right here at home, “awareness†is scheduled at a special event, “Plant This, Not That: Alternatives to Invasives,†at the N.C. Botanical Garden on Saturday, Feb. 25, at 1 p.m.

The program, reception and art exhibition is free, but reservations are required (962-0522).

It will surprise most folks that the ever-popular Nandina domestica is the poster child of this year’s awareness activities statewide. T-shirts are available for those seriously aware.

I remember years ago planting this lovely exotic for my mother-in-law, and I’m still digging seedlings out of the local forest. Like some other exotic ornamental garden plants (and not all exotics are invasive), it has been around a long, long time and only now is beginning to be an aggressive “bully,†displacing our native flora.

Julia E. Shields black-and-white nandina original appears on this year's exotic invasive T-shirt. Photo courtesy of the N.C. Botanical Garden

Recently, and irresponsibly, this dazzling, red-berried plant has been promoted in local gardening publications and newspaper columns. However, on a positive note, some nurseries do offer fruitless, non-invasive varieties of nandina.

Many gardeners simply don’t want to understand how exotic plants may be invasive, resulting in biological damage to our environment and millions of dollars lost to local economies.

How well I remember a response from a local gardener when I was describing how Chinese wisteria creeps over and destroys mature trees: “Oh it’s so beautiful, why would one get rid of it?â€

In addition to sources of information on exotic invasives on the Garden’s website (ncbg.unc.edu.com), an excellent resource for understanding the issues and discovering native alternatives to the “bully†exotics is the “Going Native: Urban Landscaping for Wildlife with Native Plants†website at N.C. State (ncsu.edu/goingnative).

The site is engaging and worth exploring. For instance, it says that recent studies indicate that birds nesting in some exotic shrubs experience poor nesting success. And exotic fruits, while attractive to wildlife, may not provide the best nutrition for native wildlife.

You may recall Mary Sonis’ beautiful image in The Citizen’s current issue of MILL of the cedar waxwing feasting on privet berries along Bolin Creek. Not only may that overabundance of privet berries be providing poor nutrition, those birds are spreading the seed from the digested berries everywhere, which accounts for the impenetrable privet thickets that, along with the thickets of Eleagnus umbellata, autumn olive, have so degraded that stream corridor.

My woods-walking buddies Brian and Tony are now referring to these invasive species as “bullies†in the native plant world, and you know what? During our walks, we frequently stop and grub out these “bullies†when we come upon them. What a great feeling on a recent walk to free some native spicebush from invading eleagnus along a stream bank. We can say we did it for the spicebush swallowtail.

So become aware of which plants are good and which are not and then take action, one plant at a time.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

“Fields of dandelion are like huge cloud rafts floating on a sea of green. Lying back on this flowery bed can become intoxicating, the mind swooning with the fragrance. Dandelions conjure up images of spring, their fresh scents so alluring, drawing one to run barefoot across their faces until the feet are green and yellow striped. It is also the lone flower of sunny winter places, defiantly blooming next to patches of mid-winter snow, always reminding us, even in the coldest times, that there is hope for spring.â€

Those words of Tom Brown, Jr. (Tom Brown’s Field Guide: Edible and Medicinal Plants) describe the lowly dandelion far more engagingly than can I.

While still pursuing “winter botany†I pause to note that early spring wildflowers – really winter annuals – like speedwells, henbits and chickweeds have been carpeting lawns and open spots all around town since the early days of January, way, way ahead of their normal appearances.

Most notably in flower is my friend the dandelion, Taraxicum officinale, the cause of grief for folks who prefer uniform green deserts of perfect lawns. It’s regrettable that Ortho products has a commercial that describes the flowering dandelion as the cause of hay fever. That image terrorizes innocent viewers to eliminate those beasts in the lawn with easy-to-apply chemical herbicides.

In reality, dandelion flowers do not produce pollen light enough to waft its way into your nostrils to make you sniffle and sneeze. In fact, for centuries worldwide, the dandelion has been a source of useful herbal medications and healthy food and drink. It’s not difficult to find countless culinary and medicinal uses and recipes. Very popular are tender young leaves, fresh or cooked. Brown’s engaging description of dandelion root coffee encourages me to go foraging across my yard this weekend.

Dandelion is described as a spring bloomer, with occasional flowers observed in every month, but very seldom during the winter months of January and February. But this year you will have noticed it has not taken a winter rest.

Though countless insect pollinators have been observed on the composite heads of 100-plus small ray flowers, the dandelion does not seem to be dependent upon pollinators to produce viable seed. As a child, you most likely played with dandelion seed heads, watching the parachute-adorned seeds soar skyward.

Now, as an adult you are likely to stoop down, pluck one, make certain no one is observing you, and with a strong puff or two, watch, in wonder, those seeds soar skyward.

Looking closely down on a dandelion flower, again I prefer Brown’s description: “The close view of the flower itself creates an image of a fiery yellow explosion that originates from a common green heart. The myriad petals forming the rich golden-yellow crown seem to fire off in every direction, yet in perfect harmony, creating a balance of unity and common understanding.â€

How wonderful if human societies could “create a balance of unity and common understanding†like that of a dandelion flower.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora columnist

Flora’s focus this week is wooly mullein, Verbascum thapsus, also called velvet-leaf, flannel-leaf, Jacob’s staff and Quaker rouge. It’s in abandoned fields, on roadsides and even in pavement openings, single or clustered in patches.

Last week a Citizen reader urged me to describe the extensive carpet of mullein on that sloping, south-facing roadside adjacent to the on-ramp from Columbia Street to the N.C. 54 Bypass going west toward Carrboro. I’ve been enjoying that growing roadside population of mullein for years, and this year hundreds of mullein rosettes are effectively carpeting the hillside. It’s also notable that interspersed within that shaggy carpet of mullein are numerous fire-ant hills, definitely to be avoided.

Generally described as a biennial, mullein grows one year, then flowers, produces seed and dies the second year. Studies have determined that some plants will germinate, grow, flower, produce seed and die in one year, and other plants may continue this short lifecycle into a third year or more. That’s quite a survival strategy.

What may seem limiting is it requires open ground to survive, so you won’t find it in forests or competing with vigorous perennials. However, its seed remains viable for up to 100 years, so it is ready to take advantage of disturbance on any site – another good survival strategy.

We have the Quakers to thank for one of the humorous common names. Not allowed to use makeup, these settlers rubbed wooly mullein leaves on the face for a long-lasting ruby blush. Quaker rouge was an effective makeup without breaking Quaker rules.

Native Americans quickly learned about the utility of this plant immigrant. Medicinal and utilitarian descriptions are endless. The Lumbee stuffed the flannel-like leaves in their moccasins for warmth in cold months. Tall dried flower stems (Jacob’s staff) served as torches. The hardness of the dried stems made it a preferred stem for fire-making hand-drills.

Fresh and dried mullein leaves and the yellow flowers have been used effectively as inhalants, teas, infusions, poultices and salves for countless injuries and ailments.

Engaging descriptions of traditional uses of Mullein are offered by Tom Brown Jr., the guru of outdoor survival training, in Tom Brown’s Field Guide: Wild Edible and Medicinal Plants. I love his description of yellow-flowering stems standing tall in green summer fields “ … that looked like people standing erect, worshiping the Creator.â€

In moderation, mullein is an engaging garden plant. I vividly remember a visit to that grand garden at Chatsworth, home of the Duchess of Devonshire in central England. To my inquiry about the mulleins growing haphazardly along pathways, the gardener responded: “Oh, that’s mullein, a favorite of the Duchess and we’re instructed not to weed a one of them!â€

In my yard I take care to nurture a few wooly mullein rosettes to enjoy throughout cold months, anticipating their tall yellow-flowered stems in mid-summer.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora.

By Ken Moore

Flora Columnist

The most obvious evergreen features of the winter forest floor are numerous extensive carpets of Christmas ferns, Polystichum acrostichoides (see Flora, “Christmas fernsâ€). Such fern carpets indicate a bit more moisture close to the soil surface than occurring in the surrounding terrain. I also admire single specimens and small clumps of ferns here and there and can’t help but wonder how many years will pass before they become impressive spreads.

Less obvious, but notable to the observant eye, are at least five small evergreen plants that are easy to identify during the winter. Several of them in the past have been called wintergreen. Some years ago when assisting Betsy Green Moyer with Paul Green’s Plant Book, I was puzzled for days trying to discern exactly which botanical species were being described as “wintergreen†by old-timers who collected them for herbal medicines.

I finally decided to limit “wintergreen†to Gautheria procumbens, which in Bell and Lindsey’s Wild Flowers of North Carolina is also called checkerberry and teaberry. A common plant of northern states and our mountain counties, this wintergreen is seldom seen down here in our Piedmont.

Become familiar with the four common evergreen wildflowers pictured here by name and you can impress your woods-walking companions.

The most frequently found is Chimaphila maculata, spotted or striped wintergreen, sometimes called pipsissewa. Pipsissewa means “to make water†and was used as an herbal diuretic. You can use whatever name you like. Return in mid-May to June to catch it in flower.

You could confuse the white-striped leaves of rattlesnake plantain, Goodyera pubescens, with the spotted wintergreen if you did not make note that Goodyera’s striped leaves remain as a rosette flat on the ground, not along a short upright stem as on Chimaphila. Return in June to July to see this terrestrial orchid in flower.

Locally there are three similar evergreen plants called wild ginger or heartleaf. Don’t fret about which species of Hexastylis you are seeing. All three have distinctively heart-shaped leaves and show varying degrees of light and dark variegation. Return in early mid-spring to discover the leathery flowers hidden beneath the leaf litter.

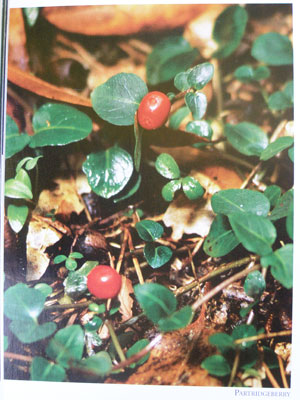

You’ll find partridge berry, Mitchella repens, either as a few sparse prostrate opposite leafy stems or as vigorous mats scattered throughout deciduous and piney forests. The red berries resulting from two joined flowers may still be present in the winter. Return in May to find white flowers.

The fifth commonly encountered evergreen wildflower, three-lobed leaved Hepatica, was featured in Flora last week.

So there you have it, your guide to identifying our five common evergreen wildflowers. Make certain you don’t confuse them with the very common crane-fly orchid, Tipularia discolor (see Flora, “Locate now for later viewingâ€). Crane-fly orchid leaves are now soaking up the winter sun, but these leaves are not evergreen; they die down during summer months.

Now you should invite your friends to join you on another winter woods walk.

Email Ken Moore at flora@carrborocitizen.com. Find previous Ken Moore Citizen columns at The Annotated Flora (carrborocitizen.com/flora).