CHAPTER

X

DEFENCE OF THE CHANNEL PORTS

22nd May to

26th May, 1940

When the German armour broke through

to the coast at Abbeville on

May the 20th, Boulogne and Calais acquired a new importance for, apart

from Dunkirk, they were then teh only ports through which the British

Army could be supplied. Lord Gort had no troops which could be spared

for their defence. Accordingly the War Office ordered the 20th Guards

Brigade to Boulogne, and from the 1st Armoured Division (which was on

the point of leaving for Cherbourg) they deflected to Calais the 3rd

Royal Tank Regiment and the newly created 30th Brigade, formed from the

infantry of the division's Support Group. As these forces set out from

England the German armoured divisions began their advance northwards

from the Somme.

The subsequent actions at Boulogne

and Calais went on

simultaneously, but once begun there was no communication between the

two: they are therefore described separately.

BOULOGNE

Boulogne had been used only as a port: no British garrison had

been stationed there. On the 20th of May anti-aircraft defences had

been provided: eight 3·7-inch guns of the 2nd Heavy

Anti-Aircraft Regiment and eight machine guns of the 58th Light

Anti-Aircraft Regiment, with one battery of the 2nd Searchlight

Regiment, mad up its total British armament.[1] The French had 'two

salvaged 75-mm. guns; two 25-mm. anti-tank guns; and two tanks, one of

which was broken down and only usable on the spot'.1

But Boulogne was not empty of troops. There was considerable

numbers of young French and Belgian recruits not yet trained for

fighting; about 1,500 British of the Auxiliary Military Pioneer Corps,

most of whom had no military training and none of whom were equipped as

fighting soldiers; and finally, smaller groups of men, mostly French,

who had made their way back from the south—'fractions of infantry

and artillery lacking uniformity … officers, non-commissioned

officers and men driven back to Boulogne by the

--153--

rapid

advance of the enemy, various

isolated detachments on the

move, troops on leave and men recently out of hospital'.2

There were

also large numbers of French refugees crowding into the town from the

surrounding country.

The 20th Guards Brigade was

training at Camberley on the morning

of May the 21st when orders were received from the War Office to

proceed immediately to Dover for service overseas. Less than

twenty-four hours later it arrived at Boulogne (having been escorted

across by the destroyers Whitshed

and Vimiera)

and began to disembark. Only two of its battalions had been ordered

out, the 2nd Irish Guards and the 2nd Welsh Guards, with the Brigade

Anti-Tank Company and the 275th Battery (less one troops) of the 69th

Anti-Tank Regiment.[2] Brigadier W. A. F. L. Fox-Pitt commanded the

brigade.

Rear General Headquarters of the British

Expeditionary Force had

moved back by now to Wimereux, three miles up the coast, and Brigadier

Fox-Pitt reported there at seven o'clock in the morning of the 22nd. He

saw the Adjutant-General, Lieutenant-General Sir Douglas Brownrigg, who

had been given instructions from the Commander-in-Chief to get rid of

all 'useless mouths' from the ports of Dunkirk, Calais and Boulogne as

soon as possible, and to go on evacuating personnel arriving at these

ports who were not of military value.[3] Brigadier Fox-Pitt was told

that enemy transport had been reported at Etaples, sixteen miles

south-east of Boulogne, and that German armoured forces were

said

to be Forest of Crécy area. The French 21st Infantry Division

was coming up to hold a line between Samer and Desvres about ten miles

south of Boulogne; it had already about three battalions deployed and

the rest of the division was being moved from the east by train.

Brigadier Fox-Pitt's orders to hold Boulogne and for this task a

regiment of tanks (the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment) and another infantry

battalion (the 1st Queen's Victoria Rifles) should join him from Calais

on the following day.

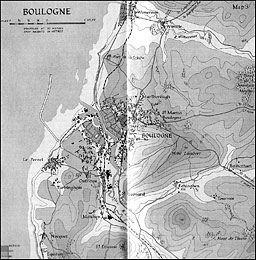

With this information in mind

the Brigadier disposed his force for

the defence of the town. The positions taken up are most easily

realised by reference to the map facing page 158. They were largely

determined by the situation of the town and the nature of the

surrounding country. Boulogne lies at the mouth of the River Liane,

which winds its way to the sea through a valley in the surrounding

hills. The comparatively level ground near the harbour is small in area

and congested by building; almost at once the town begins to climb the

hill, and the roads up to the old walled town–known as the Haute

Ville or 'the Citadel'–are steep. The river and the harbour

basins cut the lower town in half, as the map shows. The Irish Guards

held the south-

--154--

western

ground between the river west of

St Léonard and the

sea north of Le Portel; while the Welsh Guards covered the part of the

town which lies north-east of the river, holding the western slopes of

the Mont Lambert ridge and the high ground through St Martin

Boulogne.[4] Together they were extended over a six-mile perimeter;

inevitably, therefore, they were thin on the ground. A much more

considerable force would be needed to defend the position successfully,

for the ground round Boulogne is high, rolling, open country, providing

by its undulations both hidden approaches and commanding heights well

suited to the manoeuvring of armoured troops. It must be defended on

these surrounding hills, for once an enemy wins these, Boulogne lies at

his mercy. Mont Lambert ridge in particular commands most of the town

and harbour.

About fifty men of the 7th Royal West

Kent who had made their way

north after the fight at Albert, described on page 80, and about a

hundred Royal Engineers of the 262nd Field Comapny had reached

Boulogne, and they occupied positions on the right of the Welsh Guards

after destroying a road bridge across the river.[5] Brigadier Fox-Pitt

reported the dispositions of the British battalions to General

Lanquetot, commander of the French 21st Division, who had arrived with

some of his staff and was organising the defence of the town with the

various French elements available.

The German

armoured divisions whose advance had been slowed

down by the British counter-attack at Arras on the 21st had now been

ordered to resume the advance northwards. The War Diary of Guderian's

XIX Corps (1st, 2nd and 10th Armoured Divisions) has two entires on the

22nd May which are relevant to the action at Boulogne. The first is

timed at 1240: '2nd Armoured Division will advance direct to Boulogne

via the line Baincthun–Samer; 1st Armoured Division via Desvres

to Marquise, in order to protect, on this line, 2nd Armoured Diviion's

flank against attack from Calais.'3

And at the end of the day's

entries, recognising the need for quick action, 'the corps commander

sent 2nd Armoured Division towards Boulogne at noon without waiting for

orders from [Kleist] Group. In consequence the division succeeded in

penetrating to the town.'4[6]

This division had had some difficulty

in overcoming French resistance at Samer (where the French forces

consisted mainly of troops from a French divisional instruction centre)

but reached the outskirts of Boulogne and mad first contact with teh

Irish Guards in the middle of the afternoon. Soon after five o'clock

they attacked with tanks and artillery, but with Irish Guards held them

off and the attack died away about an hour. The enemy had lost a tank

and made no gain. They attacked the Welsh Guards with tanks at about

eight

--155--

o'clock

and again when darkness was

falling, but each time they

were driven off. At about ten o'clock they had their one minor success,

when in a renewed attack on the Irish Guards a post was cut off, though

some men got away.

Reports were received that

enemy armoured columns were moving

on the town from the north-east and north, but Major-General H. C.

Loyd, from Rear General Headquarters, who visited the Brigadier during

the night, assured him again that the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment, and the

1st Queen Victoria's Rifles would probably arrive from Calais early

next morning.[7] It will be found when the account of what happened at

Calais is given, that in fact no move to Boulogne was attempted, and

this was not the only hope to be disappointed. Of the troops already

deployed by the French 21st Division, those near Desvres succeeded in

holding up the advance of the German 1st Armoured Division, who,

according to their War Diary, fought vainly to overcome the French

resistance on the 22nd and were still held up at midday on the 23rd.[8]

But the bulk of the 21st Division was attacked while still entrained

and dispersed by enemy tanks. It could not now form a line south of

Boulogne. There would now be nothing but the 20th Guards Brigade and

the improvised French forces in the town to resist Guderian's attack on

Boulogne.

The Royal Air Force did their utmost to

hamper the German movement

towards Boulogne. Our fighters were in action in the coastal area and

twelve Battles, eleven Lysanders, and fifty-eight Blenheim bombers

operated; four were lost, but the losses of aircraft which the enemy

returned on this day totaled twenty-four destroyed and six damaged.[9]

At daybreak on the 23rd the German attack was resumed. For de

la

Crèche on the hill to the north was captured from the French,

and a troop of the 2nd Anti-Aircraft Regiment in the vicinity had their

guns knocked out after they had destroyed two of the enemy's tanks.

About half past seven in the morning attacks on the 20th Guards Brigade

frontage came in from all sides. Tanks and infantry supported by

artillery and mortar fire inflicted considerable casualties on our

infantry and anti-tank gunners, and some companies were forced to give

ground. By the end of a long morning's fighting it was clear that the

original perimeter could not be held, and the battalions were drawn

back to the outskirts of the town.

Throughout the

morning destroyers of the Royal Navy were coming

and going in spite of the fact that the enemy now had the harbour under

close-range artillery, mortar and machine-gun fire. In addition to

those already mentioned the destroyers Vimy, Venomous, Wild Swan and Keith were all

employed. French destroyers were also in action against short targets

and one (L'Orage)

was sunk. The commander of the Keith

was killed on his bridge and commander

--156--

of

the Vimy

was mortally

wounded.

But in harbour and off the coast the ships shelled enemy gun-sites and

machine-gun nests with conspicuous success and were of great help to

defending troops, while non-combatant and wounded men were being

steadily evacuated under the direction of a contingent of Royal Marines

brought out to deal with the large number of unorganised men reaching

the port. Meanwhile preparations to destroy port installations were

being carried out by a naval demolition party.[10] The 20th Guards

Brigade were, however, ordered to remain and fight it out.[11]

In the afternoon there was a lull in the fighting, which is

explained in an entry in the German XIX Corps War Diary: '1445. At

about this time Corps Headquarters has the impression that in and

around Boulogne the enemy if fighting tenaciously for every in ch of

ground in order to prevent the important harbour falling into German

hands. Luftwaffe

attacks on

warships and transports lying off Boulogne are inadequate: it is not

clear whether the latter are engaged in embarkation or disembarkation.

2nd Armoured Division's attack therefore only progresses slowly.'5

The German commander had asked for an air attack on the harbour which

was eventually delivered two hours later by forty to fifty aircraft,

but was partly frustrated by the Royal Air Force. Three of our aircraft

were lost but eight of the enemy were brought down and others damaged.

The German War Diary notes: '1930 hrs. The long-awaited air attack on

the sea off Boulogne temporarily relives pressure on 2nd Armoured

Division,'6[12]

and for a short time the evacuation of non-combatant

troops was interrupted.

At about half past six that

evening fresh orders were received

from the War Office. The 20th Guards Brigade were to be evacuated

immediately.[13]

By now the enemy had closed in;

the whole harbour was under fire and entry was extremely hazardous. The

Whitshead

and Vimiera

went in first and engaged enemy batteries in a fierce gun-fire duel as

they berthed. Embarkation of the Irish and Welsh Guards and Royal

Marines began, with about 1,000 leaving in each destroyer. Then the Wild Swan, Venomous and Venetia took their

places, again under a murderous fire. The Venetia

was damaged and had to back out of the harbour; and all three ships

engaged in a most unusual naval action, firing over open sights at

enemy tanks, guns and machine guns only a few hundred yards away while

they took the troops on board. They bore away about 900 men each and

later the Windsor

arrived and

took off a further 600, including man wounded and the demolition party.

The last ship to reach the stricken port was the Vimiera,

making her second trip; she entered the harbour at about 1.40 on the

morning of the 24th in an eerie silence. She remained at her

--157--

berth

over an hour and took on board 1,400

men. In this dangerously overloaded state she reached England in

safety.[14]

The Wessex had also

been

ordered to Boulogne, and had she arrived a further 300 Welsh Guards who

remained might have been brought back. But the Wessex

seems to have been diverted to Calais (see below) and no further ships

went to Boulogne. Some of the Welsh Guards who were left behind were

captured in the town next day and some later while trying to break out.

Under the leadership of Major J. C. Windsor Lewis, the remnant of his

company and detailed of other regiments, including a party of French

infantry, were established on the seaward end of the mole and held out

for a further thirty-six hours, with the enemy surrounding the basins

on either side and under heavy fire from tanks, artillery and mortars.

Only when it was clear that no more ships could get in and when food

and ammunition were giving out, did they capitulate. The French

garrison of the Citadel capitulated about the same time, after making a

sortie which was unsuccessful.[15] On May the 25th the enemy could

report that Boulogne was captured.

An entry in the

War Diary of Guderians Corps for May the 24th

reads 'As Boulogne will be threatened from the sea by English forces

especially after its capture, 2nd Armoured Division is ordered at 1400

hrs to begin preparations for the repair and re-use of the

fortifications of Boulogne, employing for this purpose prisoners of

war'.7[16]

The use of prisoners of war on such tasks is forbidden by

international agreements to which German was a party.

Further entries in the XIX Corps War Diary show that Guderian

was not pleased. The essential thing seemed to him to be 'the push to Dunkirk'

but this had been 'strangled at the outset' by ordered from Kleist

Group. The causes of the comparatively slow advance of the attack in

the north-west of France he attributes in the first place to the fact

that 'for reasons unknown to the Corps Command the attack on Boulogne

was only authorised by [Kleist] Group at 12.40 hrs on the 22nd. For

about five hours 1st and 2nd Armoured Divisions were standing inactive

on the Canche.' He complains that for the heavy attack on the two

strongly defended sea harbours of Boulogne and Calais he could only at

first use the 1st and 2nd Armoured Divisions as the 10th Armoured

Division was then in Group reserve; and he winds up his 'Conclusion' on

the 23rd of May: 'Corps' view is that it would have been opportune and

possible to carry out its three

tasks (Aa Canal, Calais, Boulogne) quickly and decisively,

if, on the 22nd, its total

forces,

i.e. all three divisions, had advanced northward from the Somme area in

one united suprise stroke.'8[17]

(It will be seen that later, when

he had been able to look at the ground, he considered

--158--

that

the use of tanks to attack Dunkirk

would entail needless sacrifice—see page 208.)

It

would indeed have been awkward for the 20th Guards Brigade if

the 2nd Armoured Division had reached Boulogne five hours earlier, but

to Rundstedt, commanding a group of armies with a long exposed flank,

with neither Amiens nor Abbeville yet securely held, and with Arras

still unconquered, the position did not look quite so simple on May the

22nd. A delay of five hours till it was seen whether the Arras

counter-attack was to be renewed was hardly unreasonable.

There

is one other aspect of British action at Boulogne which must

be noted—the aspect seen by the French—for it shows how

easily misunderstanding may arise between allies in such a confused

situation. The 20th Guard Brigade acted under orders of the British

Government. They were ordered out at short notice to defend Boulogne,

and when after fighting off the first attacks it was clear that two

battalions could not hold the town they were ordered home again at even

shorter notice. both orders seemed reasonable to British eyes.

But when Brigadier Fox-Pitt received the order to re-embark he

was

unable to communicate with General Lanquetot before leaving, for the

General's headquarters were away up in the Citadel and the enemy were

already between it and the lower town where the Guards battalions were

fighting. It will be remembered that General Lanquetot had also had

ordered to hold Boulogne with his 21st Division; that having got there

ahead of his troops, he learned that these had been intercepted and

would not join him; and that he had therefore organised what defence he

could, taking into account the dispositions of the Britisih battalions

which were only a part, though much the most substantial part, of the

town's defences. When, therefore, he learned on the morning of May the

24th that the whole British force had gone home to England during the

night, without warning him that they were doing so, it is easy to

realise that in his eyes British action appeared to be less reasonable.

And since French troops in the Citadel and only Major Windsor Lewis's

contingent in the harbour held out for a further twenty-four hours it

is east to see why the British part in the action at Boulogne appears

as a subordinate one to French eyes. The truth is that the German

armoured division was held at Boulogne by the joint action of British

and French troops.

CALAIS

The

troops who held Calais fought against overwhelming odds with a

cheerful courage and unquestioning devotion to duty which match the

finest traditions of the British Army. Unfortunately the conditions

under which they were required to fight show some of the

--159--

failings

which have been matched too often

in the conduct of our military excursions.

Infantry

were sent out short of their full complement of arms and

equipment. Of the single battery of anti-tank artillery, only eight

guns reached France; the rest were left at Dover because there was no

room for them in the ship provided for their transport. And some ships

were ordered home before they had completed the unloading of personnel,

weapons and stores which they had just ferried across. But the

handicaps were not confined to such matters as these. Within a period

of forty-eight hours contradictory orders were given to the force by

General Headquarters in France, Lord Gort's Adjutant-General, then in

Dover, and the War Office in London. It is hardly surprising that the

French commander in Calais (who came under the British Command by order

of General Fagalde) found the British intentions 'nebulous'.9

The

troops employed at Calais could not have fought more bravely than they

did, had they had all their arms and equipment; and they could not have

held Calais indefinitely had that been their single task, for the

forces against them were overwhelmingly stronger. But they would not

have fought under so great a handicap if they had been fully equipped

and if their commander had been free to concentrate on the sufficiently

arduous duty of defending the town.

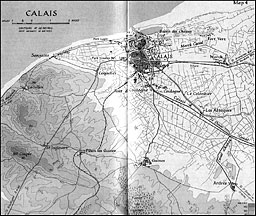

Calais lies in

flat country flanked by low sand dunes. Much of

Vauban's fortifications still enclose it, interrupted only in the

south-west by railway construction and industrial buildings. The

Citadel still guards the inner, water-ringed 'old town' and eight of

the eleven bastions still stand in the angles of the outer ramparts. On

the east face the moat still holds water and in other places the ditch

is traceable, though it is dry. Uncle Toby and Corporal Trim would find

much to interest them even now, though the 'ravelins, bastions,

curtains and hornworks' with other refinements of the fortified town

which they laboured untiringly to reproduce in Uncle Toby's garden are

blurred and buried by neglect.10

It is nevertheless a comparatively

strong defensive position, granted an adequate force to hold the

eight-mile perimeter. The criss-cross ditches in the low ground to the

east and south confine attacking vehicles narrowly to the built-up

roads which lead into the town; only on the west and south-west does

the nature of the surrounding country change as the ridge of high

ground which sprawls diagonally across northern France reaches out to

the sea between Calais and Boulogne. On that flank Calais is overlooked

from nearby hills and is an easy target for artillery situated on the

higher ground, as the map facing page 170 shows.

--160--

On

May the 19th Colonel R. T. Holland had

been appointed to

command British troops in Calais, consisting then of a single platoon

of infantry and some anti-aircraft defences.[18] Base details of the

Argyll and Sutherland Highlanders who formed the infantry platoon were

sent to guard a block on the road to Dunkirk; two batteries of the 1st

Searchlight Regiment were disposed in Forts Risban and Vert and in a

series of outlying posts outside the town; a battery of the 2nd

Anti-Aircraft Regiment had four guns near Sangatte on the west and

three near Fort Vert; and part of a battery of the 58th Light

Anti-Aircraft Regiment sited their two guns to cover lock gates in the

harbour. French troops in Calais consisting of naval personnel manning

some coast-defence guns, and various 'small fragments of units driven

back by the German advance,11

including infantry and about a company

of machine guns, were distributed in old forts outside the town, in the

citadel, and in two of the bastions on the north-west. A large and

daily-growing number of stragglers and refugees poured into the town,

greatly hampering the construction and control of road blocks and the

movement of troops when they arrived.

On May the

22nd, when the German 2nd Armoured Division was already

closing in on Boulogne and the 1st Armoured Division was moving north

from the Somme,[19] the first of the British troops now sent to Calais

began to land.

The 1st Queen Victoria's Rifles, a

first-line Territorial

battalion, arrived first. They were a motor-cycle battalion, but came

without their machines, without transports, with 3-inch mortars, and

with only smoke bombs for their 2-in mortars; many were armed only with

pistols. On disembarking they were ordered to move out at once to block

the principal roads into Calais, to guard the cable-entry at Sangatte,

and to patrol the beaches on either side of the harbour entrance so as

to prevent enemy landings there. As they had no transport, they had to

man-handle stores and ammunition.[20] Hard behind came the 3rd Royal

Tank Regiment and two hours later their vehicles arrived. Unloading

began at once, but proceeded slowly and under great difficulties. Only

the ships' derricks were workable as electricity had been cut off from

dockside cranes. Moreover, 7,000 gallons of petrol in tins, stacked on

deck, had to be landed before the tanks and vehicles in the holds below

could be unloaded and refueled. The stevedores had been working without

rest for many hours unloading rations for the British Expeditionary

Force and they were nearing the point of exhaustion. Although the work

went on nearly all night, unloading was not completed till well on in

the following day.

--161--

A

five o'clock in the afternoon of the

22nd General Sir Douglas

Brownrig, passing through Calais on his way from Wimereux to Dover,

ordered the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment to proceed south-westwards, as

soon as landing was completed, in order to join the 20th Guards Brigade

in the defence of Boulogne (page 154).

The tanks were accordingly ordered to assemble in the area of Coquelles

ont he road which runs from Calais to Boulogne. They consisted of

twenty-one light tanks and twenty-seven cruisers.

Six

hours later a liaison officer brought other orders from

General Headquarters. The tank regiment was to proceed as soon as

possible south-eastwards

to

St Omer and Hazebrouck, where contact was to be made with General

Headquarters. As the regiment could not be ready to move for some time,

a patrol of light tanks was sent to reconnoitre the road to Sm Omer. It

found the town unoccupied but under enemy shell-fire and lit by the

flames of burning houses; it rejoined the regiment near Coquelles,

without having encountered enemy troops, about eight o'clock on the

morning of the 23rd.[22] It had been very fortunate, for leading units

of the German 6th Armoured Division (of Reinhardt's XXXXI Corps) had

lain that night round Guines, only a few miles west of the St Omer

road. The division had been advancing northwards but had been ordered

to turn east to St Omer while the 1st Armoured Division came up to take

Calais.[23]

As already mentioned, the 3rd Royal

Tank Regiment had been

detached from the British 1st Armoured Division which was on the point

of being sent to Cherbourg. The 30th Brigade was ordered to Calais at

the same time.[24] It left Southampton on the 22nd, arrived at Dover

early on the 23rd, and sailed again for Calais during the morning. At

Southampton Brigadier C. N. Nicholson, commanding the brigade, was

informed by the War Office that some German tanks with artillery were

moving in the direction of Boulogne, but the general situation was

obscure; the 30th Infantry Brigade would land either at Calais or

Dunkirk and would then be used offensively against the German columns.

At Dover Brigadier Nicholson saw Lord Gort's Adjutant-General newly

back from Calais. Sir Douglas Brownrigg did not know that the orders

which he had there given to the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment before leaving

France had since been superseded by different orders from

General

Headquarters, and he instructed Brigadier Nicholson that the 30th

Brigade was to proceed with the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment to the relief

of Boulogne as soon as possible.[25] With this order Brigadier

Nicholson sailed for France.

Meanwhile the 3rd

Royal Tank Regiment at Calais, having received

their patrol's report on St Omger, sent an escort of light tanks to

protect the liaison officer returning to General Headquarters. But by

then the German 6th Armoured Division was again on the

--162--

move

going eastward towards St Omer;[26]

the road from Calais to

St Omer was no longer clear. Our light tanks quickly ran into advanced

elements of the enemy armoured division and all were lost in the

ensuing fight. Only the liaison officer's faster car got back to Calais

with its occupant wounded.[27] The remainder of the Tank Regiment had

begun to follow the advance party from their assembly area near

Coquells. But the German 1st Armoured Division were also moving and had

deployed tanks and anti-tank guns on the high ground covering Guines as

they turned north-eastwards towards Gravelines.[28] The British tanks

soon met these on their way to the St Omer road and, though they drove

off the light tanks which were first met, the heavier tanks and

anti-tank guns were too strong for them to master. After knocking out

some of the enemy's tanks but losing twelve of their own it became

clear that they could not break through the German division to St Omer.

Accordingly they fell back on Calais.

Meanwhile

other units of the German 1st Armoured Division on their

way to Gravelines encountered at Les Attaques a detachment of the 1st

Searchlight Regiment, which after putting up a stout defence was

surrounded and overwhelmed.[29] The enemy's tanks and infantry then

attacked a post at Le Colombier, but with the help of fire from other

posts and from guns of the 58th Light Anti-Aircraft Regiment on the

rising ground near Boulogne these were driven off.[30]

Thus

when the 30th Brigade convoy docked at Calais on the

afternoon of May the 23rd Brigadier Nicholson found that the 3rd Royal

Tank Regiment had already had considerable losses, that the enemy were

closing in on the town, and that it was not possible to move either

south-east to St Omer or south-west to Boulogne. It was indeed clear to

him that the one urgent task was to organise the defence of Calais

itself. Accordingly he ordered the infantry battalions of the 30th

Brigade—the 1st Rifle Brigade (on the east) and the 2nd King's

Royal Rifle Corps (on the west)—to hold the outer ramparts behind

the advanced posts of the Queen's Victoria Rifles and the outlying

anti-aircraft units.[31]

But he had hardly made

these dispositions when, shortly after four

o'clock in the afternoon, he received yet another order, this time from

the War Office. He was now instructed to convey 350,000 rations for the

British Expeditionary Force north-eastwards

to Dunkirk and he was told to regard this duty 'as over-riding all

other considerations.[32] So he recalled part of the infantry from the

perimeter defence and sent them to picket the first stretch of the road

to Dunkirk while the convoy was formed. By now yet another German

armoured division—the 10th—had come up from the south and

was shelling Calais from the high ground which overlooks it.

An

hour before midnight the 3rd Royal Tank Regiment sent a

--163--

squadron

of tanks to reconnoitre the road

to Dunkirk which the

convoy must take. They soon ran into troops with which the German 1st

Armoured Division was blocking the road from Calais to protect its own

rear as it advanced to Gravelines.[33] Three of our tanks broke through

and went on to join the British troops at Gravelines; the rest were

lost. But this was not known in Calais and in the morning when nothing

was heard from the squadron another squadron went forward with a

company of the 1st Rifle Brigade to contact the advance party and to

clear the road for the convoy. Infantry and tanks fought hard to

dislodge the enemy rearguard which they found astride the road but the

latter had deployed field artillery and anti-tank guns, and when losses

mounted and no progress was made the attack was called off by Brigadier

Nicholson and the troops were ordered back to Calais. The 3rd Royal

Tank Regiment was by now reduced to nine cruiser and twelve light

tanks.[34] Between our remaining twenty-one tanks and Gravelines was a

German armoured division and it was clearly impossible to get the

convoy through.

Calais was by then under heavy

shell-fire. The artillery and

mortar bombardment had started at dawn on the 24th in preparation for

an attack by the 10th Armoured Division which was launched by tanks and

infantry against the western and south-western sectors. On the west

Sangatte was abandoned, and everywhere the outlying searchlight,

anti-aircraft, and infantry detachments were withdrawn to join the

infantry holding the ramparts. The first heavy attacks that morning

were all stopped, except at one point in the south where the enemy mad

some headway and the defence was penetrated. But there a prompt

counter-attack by the King's Royal Rifle Corps supported by tanks of

the Royal Tank Regiment drove the enemy back and restored the original

position.[35]

Shells were now reaching the harbour

area, where a hospital

train full of wounded men waited for a ship; and in a laudable desire

to get there away the Control Staff ordered them to be put aboard ships

which had not yet completed the unloading of vehicles, weapons and

equipment of the infantry battalions, and supply personnel of the tank

regiment which had landed in Calais the day before. The stevedores and

other non-fighting troops were embarked at the same time and returned

to England. :It may be that further unloading was considered

unnecessary, for early that morning Brigadier Nicholson was informed by

the War Office that evacuation had been decided on 'in principle' and

that, while fighting personnel must stay to cover the final evacuation,

non-fighting personnel should begin embarking at once.[36] But it was

unfortunate that the fighting troops were thus deprived of weapons and

equipment which they sorely needed.

In the

afternoon the enemy launched further heavy attacks on all

three sides using infantry and tanks. On the west Fort Nieulay was

--164--

surrendered

by the French commander of the

garrison (which

included a small detachment of the Queen Victoria Rifles) after very

heavy shelling, and French marines in Fort Lapin and manning coastal

defence guns disabled their guns and got away. In the south the British

defence was pierced, and the enemy gained a foothold in the town from

which he could not be dislodged. The defenders of the ramparts had been

troubled all day by fifth-column sniping from buildings in their rear;

they were now enfiladed by fire from the houses held by the enemy.

Ammunition on the ramparts was beginning to run short. All but

two

of the 229th Battery's anti-tank guns had been put out of action. The

German 10th Armoured Division War Diary's entry at four o'clock that

afternoon reads 'Enemy resistance from scarcely perceptible positions

was however so strong that it was only possible to achieve quite slight

local success', and three hours later Corps Headquarters were hold that

a third of the German equipment, vehicles and personnel and 'a good

half of the tanks' were casualties; the troops were 'tired out.12[37]

Yet Brigadier Nicholson realised that he could not hold the

outer

perimeter much longer, for he had no reserve with which to counter any

penetration. A further message from the War Office confirmed the

decision to evacuate, but final evacuation of fighting troops would not

take place until seven o'clock next morning.[38] On this information

Brigadier Nicholson shortened his front by withdrawing the infantry to

the line of the Marck Canal and the Boulevard Léon Gambetta.

There was further fighting there and after dark the defenders were

withdrawn to the old town and the quadrangle to the east, which is

enclosed by the outer ramparts and the Marck and Calais canals. The

chief danger-point in this new defence line were, of course, the

bridges. It had been understood that the French would prepare these for

demolition, but this had not been done and the British force had

neither explosives nor equipment for the task.

While

the troops were withdrawing through the town that afternoon,

Brigadier Nicholson received a message from the C.I.G.S. in London in

forming him that the French commander in the north 'forbids

evacuation'.[39] This was expanded by a message sent just before

midnight: 'In spite of policy of evacuation given you this morning,

fact that British forces in your area now under Fagalde who has ordered

no, repeat no, evacuation, means that you must comply for sake of

allied solidarity …'[40] Brigadier Nicholson's role now, he was

told, was to hold on, and as the harbour 'was now of no importance to

the B.E.F.' he was to select the best position in which to fight to the

end. Ammunition was being sent but no reinforcements. But the

--165--

48th

Division 'started marching to your

assistance this morning'.

Unfortunately this last information was mistaken; the 48th Division was

required for the defence of Cassel and Hazebrouck, and was never

ordered to march on Calais.

Brigadier Nicholson's

only recorded comment on this order to fight

it out 'for the sake of allied solidarity' was recorded by Admiral Sir

James Somerville who crossed the Channel that night to confer with him:

'Given more guns which were urgently needed, he was confident he could

hold on for a time.'[41] He agreed with the Admiral that ships in the

port could now serve no useful purpose by remaining.

There

are two other laconic entries in the records of those who fought at

Calais which illustrate the spirit of the defence.

After

noting that in the early evening of May the 24th an enemy

aircraft dropped leaflets stating that Boulogne had fallen and calling

on the Calais garrison to surrender—they were to lay down their

arms and march out on the Coquelles road, otherwise the bombardment,

which would cease for an hour, would be renewed and

intensified—the writer merely adds: 'Teh company took advantage

of the lull to improve its position to give better all-round protection.

During the morning of May the 25th the Mayor of Calais (who

was

captured when our troops withdrew to the old town) was brought under

enemy escort to where the 2nd King's Royal Rifle Corps held the front,

with a proposal for Brigadier Nicholson to surrender. 'the Mayor was

detained under guard and his escort returned to the enemy' is the only

comment.[43]

At daybreak on the 25th the

enemy resumed his bombardment,

concentrating now on the heart of the old town. Collapsed buildings

blocked the streets, fire fanned by a high wind raged unchecked on

every hand; the smoke of explosions and burning houses be-clouded the

scene of destruction and obscured the movements of troops. As the day

wore on the dust and choking smoke mad the garrison's task more and

more difficult. The troops had been fighting for three days and were

much reduced by casualties, the last remaining guns of the 229th

Anti-Tank Battery were knocked out, and only three tanks of the 3rd

Royal Tank Regiment remained in action.[4]] Food and ammunition were

difficult to distribute and some went short, and water was scarce as

the mains had burst and the little that could be got from half-ruined

wells. The German artillery and mortar fire grew in intensity as the

day wore on, and the defence had not artillery with which to reply,

though the Royal Navy did their best to help by shelling enemy guns

positions.

On the east side, where the 1st Rifle

Brigade and detachments of

the Queen Victoria's Rifles held the outer ramparts and the Marck and

Calais, the enemy fought hard to break through. An attempt was mad by

the defence to organise a sortie in order to

--166--

relieve

pressure, but the carriers which

were to attack from the

north and take the enemy in the flank got bogged down in sandhills and

the attempt had to be abandoned. In the end the enemy succeeded in

breaking across the canals at a number of places. The positions of the

defenders being thus turned, they fell back fighting to the area of the

Bassin des Chasses, the dock railway-station and the quays.

Meanwhile

the King's Royal Rifle Corps, and other detachments of

the Queen Victoria's Rifles in the old town, fought grimly to hold the

three main bridges into the town from the south. Two were

held,

but the enemy won the third with the help of tanks and established

himself in houses north of the bridge, where he was pinned down. A

mixed British and French force held a key bastion and the French

garrison in the Citadel fought off all attacks upon it though

sustaining heavy casualties. Brigadier Nicholson established there a

joint headquarters with the French commander.

During

the afternoon a flag of truce was brought in by a German

officer, accompanied by a captured French captain and a Belgian

soldier, to demand surrender.[45] Brigadier Nicholson's reply as

recorded, in English,

in the German War Diary was:

- The

answer is no as it is the British Army's duty to fight as well as it is

the German's.

- The

French captain and the Belgian soldier having not been

blindfolded cannot be sent back. The Allied commander gives his word

that they will be put under guard and will not be allowed to fight

against the Germans.[46]

Thereafter the attack was renewed and only broken

off finally,

says the German 10th Armoured Division War Diary, because 'the Infantry

Brigade Commander considers further attack pointless, as the enemy

resistance is not yet crushed and as there is not enough time before

the fall of darkness'.13[47]

About two o'clock in the afternoon the Secretary of State for

War (Mr Eden) had sent Brigadier Nicholson a message which read:

Defence of Calais to the

utmost if of highest importance to our

country as symbolising our continued cooperation with France. The eyes

of the Empire are upon the defence of Calais, and H.M. Government are

confident you and your gallant regiments will perform an exploit worthy

of the British name.[48]

Shortly

before midnight the War Office sent a further exhortation

which read:

Every

hour you continue to exist is of greatest help to the B.E.F.

Government has therefore decided you must continue to fight. Have

greatest admiration for your splendid stand.[49]

--167--

This

was intercepted, read with great

interest and recorded in the War Diary of the German XIX Corps.[50]

Early in the morning of May the 26th the German bombardment

was

resumed with greater violence, additional artillery having been brought

up from Boulogne.[51] In the words of the Corps War Diary: '0900 hrs.

The combined bombing attack and artillery bombardment on Calais Citadel

and on the suburb of Les Baraques are carried out between 0900 and 1000

hrs. No visible result is achieved; the fighting continue and the

English defend themselves tenaciously.'14[52]

Les Baraques is

between the Citadel and Fort Lapin.

There was also

much heavy dive-bombing, and though one aircraft

was shot down and the tanks and infantry which followed up each air

attack were repeatedly driven off, the defenders were gradually forced

back into the northern half of the old town. The Citadel, after renewed

assaults, was surrounded and isolated from the town—and in the

town itself and in the bastions most of the defenders, by the

afternoon, fought in parties which were separated from each other alike

by the course of the battle and by piles of broken masonry. In the late

afternoon the enemy broke into and captured the Citadel with Brigadier

Nicholson and his headquarters;[53] and as evening came one group after

another of those who fought on in the town were surrounded and

overwhelmed. Gradually the fighting ceased and the noise of battle died

away as darkness shrouded the scene of devastation and death.

The reader who has already followed the fortunes of the

British

Expeditionary Force may perhaps doubt the value at this date of the

contribution to 'allied solidarity', but will have no doubt about the

service rendered by the little garrisons of Boulogne and Calais to the

British Expeditionary Force and the French First Army. They engaged two

of Guderian's three armoured divisions and held them during most

critical days. By the time the Germans had taken Calais and Boulogne

and had 'sorted themselves out', the divisions of the British III Corps

had been moved west to face them, covering the rear of the British

Expeditionary Force and guarding the routes for the final withdrawal to

Dunkirk.

The 20th Guards Brigade at Boulogne were

fortunate in that, having

proved their mettle, they were withdrawn to fight another day. The 30th

Brigade and the rest of the Calais garrison were less fortunate in

that, having proved their mettle, they were withdrawn to fight another

day. The 30th Brigade and the rest of the Calais garrison were less

fortunate in that regard, but they gained the distinction of having

fought to the end, at a high cost of life and liberty, because this was

required of them. They helped to make it possible for the British

Expeditionary Force to reach Dunkirk and by their disciplined courage

and stout-hearted endurance they enriched the history of the British

Army.

--168--

Officers

and men, many of them wounded,

who fell into the enemy's

hands that Sunday evening and went with Brigadier Nicholson into

captivity which was to last for years, compiled a number of records of

what happened in Calais. Brigadier Nicholson had not finished writing

his own version when he died in a German prisoner-of-war camp. But

other versions were completed and they give a detailed and vivid

picture of the fighting till, in the end, its coherence dissolved as

dwindling groups fought uncoordinated actions in the rubble. Any

student of these accounts must be struck by the high spirit with which

their tale is told, by the unquestioning loyalty which all-unconciously

they reveal. Nowhere is there any sign of the bitterness of defeat, any

hint of complaint, any suggestion that they were hardly used. There is

only a plain account of the fight they fought, and a sober satisfaction

in what they did. One regimental record, written by an infantryman

during the years of his imprisonment, concludes with a sentence which

typifies the spirit of them all: 'It would not be easy to find any who

regret the days of Calais.'[54]

They were

picturesquely, if inaccurately, described in the War

Diary of the German 10th Division, as belonging, for the most part to

'the Queen Viktoria Brigade, a formation well known in English military

and colonial history'.15[55]

In order that the military action at Calais could be read as

an

uninterrupted story the Royal Navy's part in the operations has been

left to the end. It began with the transhipment of the troops and the

sending over of the usual demolition party. It continued at intervals

with the landing of rations and ammunition, the embarkation of wounded

and the bombardment of shore targets. It ceased only when the German

ordered that no further evacuation, would take place. The ships

employed included the destroyers Grafton,

Greyhound, Wessex, Wolfhound and Verity and the

Polish ship Burza.

Of these the Wessex

was sunk by enemy bombers and the Burza

was damaged. And when evacuation of the fighting troops was topped Sir

Bertram Ramsay, the Vice-Admiral, Dover, sent over a number of small

craft in the hope that more of the men not required for the garrison

might still be got away. The launch Samois made four

trips into the beleagured port and each time brought away casualties,

and the echo-sounding yacht Conidaw

berthed early on the 26th, grounded on a falling tide and remained

there under fire till the tide rose again in the afternoon, and then

sailed with 165 men including a remnant of the Royal Marine

harbour-guard whose officers had all been killed or captured.[56]

Others similarly brought away many of the casualties. Only after the

fighting ceased and Calais was in enemy hands did the Navy's efforts

also come to an end.

--169--

The

Royal Air Force put forth a big effort

to cover our troops in

the coastal area during these days. Their intervention in the Luftwaffe's

attack on Boulogne on the 23rd has already been mentioned (page 156).

On the 24th twenty fighter patrols at squadron strength were flown and

there were some hard combats with much larger German formations. Ten of

our aircraft failed to return; but the enemy lost in all twenty-four

aircraft and had twelve seriously damaged. On the 25th there were

twenty-one bomber sorties by day (on which two Blenheims were lost) and

151 fighter sorties when, again, two aircraft were lost. But the enemy

return of daily losses shows twenty-five lost and nine damaged. Finally

on the 26th a similar programme was carried out. No bombers and only

six out of 200 fighters employed were lost. The German Air Situation

Reports complain of strong fighter opposition in the coastal area, the

enemy aircraft 'operating from bases in southern England'. According to

their return of daily losses over France and Belgium 160 of their

aircraft were destroyed or damaged in the five days of 22nd to 26th

May. In the same period our corresponding total was 112.[54]

There

is a footnote to this story. At first light on May the 27th,

in response to a request from the War Office received on the evening of

May the 26th, twelve Lysanders dropped supplies of water in Calais and

at ten o'clock in the morning seventeen Lysanders dropped supplies of

ammunition in the Citadel while nine Fleet Air Arm Swordfish bombed

enemy gun posts near the town. Three Lysanders failed to return and one

of the Hectors which accompanied the Swordfish crashed at Dover.[58]

But unknown to Whitehall the Citadel had fallen before the War Office

request was made to the Air Ministry; Calais was in enemy hands on the

evening before the Lysanders set out on their costly mission.

--170--

Contents

* Previous

Chapter (IX)

* Next

Chapter (XI)

Transcribed and formatted

for HTML by David Newton,

HyperWar

Foundation