Chapter IV

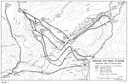

Breaking the Blockade of ChinaOf the three moves by NCAC, only one was aimed toward China. The drives down the Railway Corridor and toward the Shweli would keep the Japanese away from the trace of the projected line of communications, but only the easternmost drive--down the Myitkyina-Bhamo road--could clear the way for vehicles and gasoline to enter China on the ground. As the Chinese New First Army (30th and 38th Divisions) completed preparations for the 15 October 1944 offensive, a reconnaissance east from Myitkyina toward China revealed that the Japanese grip had already been pried from the northeast corner of Burma. (See Map 6)

Maj. Benjamin F. Thrailkill, who as a lieutenant colonel later commanded the 2d Battalion of the 475th at Tonkwa, left Myitkyina on 27 August with a company of Chinese and a platoon of U.S. infantry, plus engineers, signal, medical, and OSS personnel, with orders to establish contact with the Chinese from Yunnan. Moving east via Fort Harrison (Sadon), Thrailkill and his force met the Yunnan Chinese on 6 September in the Kambaiti Pass (Kauliang Hkyet). Eight days later Thrailkill and his men were back at Myitkyina.

The Thrailkill expedition, as it came to be called, established that the trail to China was passable, with numerous dropping ground and camp sites. The local inhabitants were thought to be friendly toward the Americans, but not to the Chinese. No Japanese were met.1

NCAC Drives Toward China

The initial NCAC orders to General Sun Li-jen's New First Army called for it "to advance rapidly on Bhamo, destroy or contain enemy forces there; seize and secure the Bhamo-Mansi area, and be prepared to continue the advance."2 The key point was Bhamo, the second largest town in north Burma and the end of navigation on the Irrawaddy. Before the war the

town had been a thriving river port; the great 400-foot river steamers had brought cargoes and passengers from Rangoon to Bhamo for the short overland trip to China. When in May 1944 the Chinese and Americans had struck Myitkyina that town had had only the defensive capabilities inherent in any inhabited locality. Nevertheless it had held out till August. Now, in the fall of 1944, the Chinese in north Burma faced a town that not only possessed natural defenses but had been strongly fortified in addition. Bhamo's military importance lay in that it dominated the ten-mile gap between the Irrawaddy River and the plateau that is the eastern side of the Irrawaddy valley. Through that space the Ledo Road would have to be built.

A force moving from Myitkyina to Bhamo in October 1944 would find a good prewar road connecting the two towns. The road did not parallel the Irrawaddy closely, but had been placed on higher ground to the east, in the foothills, to lift it above the monsoon floods. The wooded hills and the tributaries of the Irrawaddy that cut across the road offered obvious opportunities to a defending force. Of these tributaries the Taping is the most considerable.

Entering the Irrawaddy just above Bhamo, the Taping is a large river in its own right. Its sources extend so far into the plateau that marks the Sino-Burmese border that one of its own tributaries flows past the city of Tengchung where there had been some of the heaviest fighting of late summer 1944 between Chinese troops seeking to break into Burma from that side and the Japanese 56th Division trying to keep a block on the Burma Road.

Japanese documents dated early September 1944 and captured a few weeks later showed that the Japanese planned to delay around Bhamo in three stages. In the first, the Japanese outpost line would be defended from Sinbo on the Irrawaddy to Na-long on the Myitkyina-Bhamo road, about halfway down to Bhamo, and thence to the upper reaches of the Taping River. The second Japanese line was the Taping River, whose crossings were to be fortified. The third stage was Bhamo itself.

These lines were manned by the 2d Battalion, 16th Regiment, and the Reconnaissance Regiment of the 2d Division. The division was ordered to hold the outpost line until 20 September, the line of the Taping to mid-November, and Bhamo itself to late December.3 These time limits seem not to have been known to the individual Japanese, who were exhorted:

As it was with the heroes of Myitkyina, so it must be with the Bhamo garrison. . . . Do not expect additional aid. . . . Each man will endeavor to defend his post to the

utmost--to the death . . . If, for the success in the large sense, units in dire straits are overlooked in the interests of larger units do not expect to be relieved, but be cognizant of the sacrifice you as an entity will make to insure the success of the whole.4

The 38th Division led the advance of the New First Army and was charged with taking Bhamo. Possibly because D Day was 15 October, more than three weeks after the date to which the Japanese had planned to defend their outpost line, the Sinbo-Na-long line was crossed without incident. With the 113th Regiment in the lead the Chinese moved right down the road to Bhamo without a significant contact until 28 October when Japanese patrols were met two miles north of the Taping River, the next Japanese defense line. These were brushed aside, and the 113th was on the river bank, occupying Myothit.

Here was the Japanese outpost line of resistance; the Chinese patrols speedily found that the Japanese meant to defend it. Strong Japanese positions were seen on the south bank, and the commander of the 38th Division, General Li Huang, saw that he would have to force a defended river line unless he could turn the Japanese position. General Li decided to use the 112th and 114th Regiments, which had been the main body of the 38th, as an enveloping force. Since they were some seven miles to the north the 112th and 114th were out of contact with the Japanese and well placed to make a wide swing to the east. The two regiments began their march through the hills, while the 113th made a show of activity around Myothit to keep the Japanese attention focused there.

Once again envelopment proved its worth. The Japanese were too few to defend a long line, and the enveloping force was able to cross the Taping at an unguarded bridge upstream, go around the right end of the Japanese outpost line of resistance, and emerge on the Bhamo plain on 10 November. Pressing on west toward Bhamo, the enveloping force met a strong entrenched Japanese force at Momauk, which is eight miles east of Bhamo and is the point at which the Myitkyina-Bhamo road swings to the west for the last stretch into Bhamo. Here there was savage fighting between the 114th Regiment and the Japanese defenders. Heavily outnumbered, the Japanese outpost at Momauk was driven into the main defenses at Bhamo. The appearance of its survivors, some without rifles, others without shoes, depressed the Bhamo garrison.5

Meanwhile, the 113th Regiment at Myothit on the Taping River profited by these diversions to force a crossing. Then, instead of coming down the main road, the 113th went west along the Taping's south bank, where there

GENERAL SULTAN AND GENERAL SUN LI-JEN, commanding the Chinese New First Army, examine enemy equipment left behind at Momauk, Burma, by fleeing Japanese troops.was a fair road, and came at Bhamo from due north. The Japanese sought to delay along the road and at one point, Subbawng, three miles north of Bhamo, appeared ready to make a fight of it. Here the 113th's commander elected to rely on the unexpected. Leaving a small force to contain the garrison of Subbawng, he moved south directly across the face of the defenses, at close proximity, and only ended his march when he was south and southeast of Bhamo in the suburbs of U-ni-ya and Kuntha. As a result of these several and rather intricate maneuvers--with the 114th Regiment attacking west from Momauk, the 113th cutting between the Momauk outpost and the Bhamo garrison, and the 112th bypassing the fighting completely to move on down the Bhamo road toward Namhkam--a loose arc was drawn around the Japanese outposts in the Bhamo suburbs, with the 113th holding the south portion of the arc and the 114th the north.6

Finally facing Bhamo, the Chinese saw a town that was deceptively pleasant in appearance. Bhamo, lying between the Irrawaddy River to the west and a ring of lagoons to the east, seemed like a city in a park. Unlike the close huddle of buildings and shops that is the usual settlement in Asia, Bhamo reflected the years of peace under British rule in Burma, for its homes and warehouses were spread out among grassy and wooded spaces. The Burmans, Shans, and Kachins who worked in Bhamo tended to cluster together in suburban communities. Over all were the pagoda spires. But each of these features, so attractive in peace, held a menace to the Chinese. The almost complete ring of lagoons channeled the attack. The spaces between buildings gave fields of fire to the defense. The pagodas were natural observation posts. And the thick brick and concrete walls that had been meant to give coolness now gave protection against Chinese shells and bullets. The Japanese were known from aerial photography to have been fortifying Bhamo; how well, the infantry would soon find out.7

Attack on Bhamo

The first Chinese attack on Bhamo itself was given the mission of driving right into the city. Made on the south by the Chinese 113th Regiment, the attack received heavy air support from the Tenth Air Force. It succeeded in moving up to the main Japanese defenses in its sector, but no farther. American liaison officers with the 113th reported that the regimental commander was not accepting their advice to co-ordinate the different elements of the Allied force under his command or supporting him into an artillery-infantry-air team, and that he was halting the several portions of his attack as soon as the Japanese made their presence known.8

However, the 113th's commander might well have argued that he and his men faced the most formidable Japanese position yet encountered in Burma. Aerial photography, prisoner of war interrogation, and patrolling revealed that the Japanese had been working on Bhamo since the spring of 1944. They had divided the town into three self-contained fortress areas and a headquarters area. Each fortress area was placed on higher ground that commanded good fields of fire. Japanese automatic weapons well emplaced in strong bunkers covered fields of sharpened bamboo stakes which in turn were stiffened with barbed wire. Antitank ditches closed the gaps between the lagoons that covered so much of the Japanese front. Within the Japanese positions deep dugouts protected aid stations, headquarters, and communications

centers. The hastily improvised defenses of Myitkyina were nothing like this elaborate and scientific fortification. Manned by some 1,200 Japanese under Col. Kozo Hara and provisioned to hold out until mid-January 1945, Bhamo was not something to be overrun by infantry assault.9

Meanwhile, north of Bhamo, where the Chinese had not moved closer to the city than the containing detachment the 113th had left opposite the Japanese outpost at Subbawng, the 114th was making more progress. That regiment bypassed the Subbawng position on 21 November and moved two miles west along the south bank of the Taping River into Shwekyina. Outflanked, the Japanese quickly abandoned Subbawng and the rest of the 114th came up to mop up the Shwekyina area, freeing advance elements of the 114th to move directly south through the outlying villages on Bhamo.

On 28 November the 114th was pressing on the main northern defenses of Bhamo. In this period of 21-28 November the division commander, General Li, did not alter the mission he had given the 113th of entering Bhamo, but by his attention to the 114th he seemed to give tacit recognition to the altered state of affairs.10

The Chinese lines around Bhamo were strengthened by putting the 3d Battalion of the 112th into place on the southern side between the Irrawaddy River and the road to Namhkam. This permitted a heavier concentration of the 113th east of Bhamo, and that unit was given another chance at a major attack. Such an effort would be supported by twelve 75-mm., eight 105-mm., and four 155-mm. howitzers and a company of 4.2-inch mortars.11 Supported by air and medium artillery, the 113th on the east again showed itself willing to move up to the Japanese defenses but no further. Moreover, it did not appear able to take advantage of the artillery concentrations laid down for it. At this point, an American division commander would have relieved the 113th's commander, but the Chinese response was to shift air and artillery support to the 114th.

The 114th's aggressive commander had been most successful in the early days of December. With less than half the air support given the 113th and with no help from the 155-mm. howitzers, he had broken into the northern defenses and held his gains. The decision to give the 114th first call on artillery support posed a problem in human relations as well as tactics. This was the first time the 38th Division had ever engaged in the attack of a fortified town. All its experience had been in jungle war. Faced with this new situation, the 113th Regiment's commander seemed to have been at a loss to know what to do. The 114th, on the contrary, had gone ahead with conspicuous success on its own, and now was being asked to attempt close co-ordination

with artillery and air support. Its commander hesitated for a day, then agreed to try an attack along the lines suggested by the Americans.12

The tactics developed by the 114th Regiment by 9 December took full advantage of the capabilities of air and artillery support. Since the blast of aerial bombardment had stripped the Japanese northern defenses of camouflage and tree cover it was possible for aerial observers to adjust on individual bunkers. So it became practice to attempt the occupation of one small area at a time. First, there would be an artillery preparation. Two 155-mm. howitzers firing from positions at right angles to the direction of attack would attempt to neutralize bunkers in an area roughly 100 by 300 yards. Thanks to the small margin of error in deflection, the Chinese infantry could approach very close to await the lifting of fire. The 105's would lay down smoke and high explosive on the flanks and rear of the selected enemy positions. Aerial observers would adjust the 155's on individual positions. When it was believed that all Japanese positions had been silenced the Chinese infantry would assault across the last thirty-five yards with bayonet and grenade.13

Meanwhile, the Japanese 33d Army sent a strong task force under a Colonel Yamazaki to attack toward Bhamo in the hopes of creating a diversion that would cover the breakout of the Bhamo garrison. Comprising about 3,000 men with nine guns, the Yamazaki Detachment moved north from Namhkam the evening of 5 December to move on Bhamo via Namyu.14 Operating south of Bhamo was the Chinese 30th Division, which had been ordered to move on down the general line of the Bhamo road to take Namhkam. Twenty-two miles south of Bhamo the leading regiment, the 90th, encountered rough country, with hills up to 6,000 feet, and six miles farther on the first Japanese patrols and outposts were encountered. The 2d Battalion, on the far right, pulled up along a ridge about 1 December. The dominant height in the area, Hill 5338, was the object for the next ten days of operations that to American liaison officers appeared prolonged beyond all reason. When it was finally occupied, the Japanese immediately began attacking in strength, and the battalion soon showed itself as stubborn in defense as it had been lethargic in attack.15 These Japanese attacks, regarded as a reaction to the loss of Hill 5338, were actually the Yamazaki Detachment making its arrival known.

To the left of the 2d Battalion, across the road, was the 1st Battalion, with the mission of keeping contact between the 90th Regiment and the rest of the division and of protecting a battery of the division artillery. In attempting

FRONT-LINE POSITION, 30th Chinese Division sector. Two American liaison officers discuss the tactical situation.to execute this mission the battalion spread itself over a two-mile front. On the night of 9 December the battalion received a heavy bombardment followed by a Japanese attack which penetrated its lines and isolated its 1st and 2d Companies. This was bad enough, but worse followed the next morning. Colonel Yamazaki massed three battalions in column to the east of the road, and, attacking on a narrow front, broke clean through by leap-frogging one battalion over another as soon as the attack lost momentum. The third Japanese battalion overran the 2d Artillery Battery, 30th Division, and captured four cannon and 100 animals. The battery commander died at his post.16

The Chinese were not dismayed by the setback but fought with a spirit novel to the Japanese. The 88th Regiment swung its forces toward the Japanese penetration, which was on a narrow front, and since the terrain was

hilly in the extreme the Japanese could see Chinese reinforcements converging on the battle site. So vigorously did the Chinese counterattack that one lone Chinese soldier fought his way almost into the trench that held Colonel Yamazaki and the 33d Army liaison officer, Colonel Tsuji. Writing in his diary, Tsuji remarked: "This was the first experience in my long military life that a Chinese soldier charged Japanese forces all alone."17

The Chinese, comprising as they did three regiments of a good division, could not be indefinitely withstood by the four Japanese battalions. Destroying the four pack howitzers they had captured, the Japanese sought only to hold their positions until the Bhamo garrison could escape.18

Meanwhile, within Bhamo, the Japanese garrison was making preparations to break out. Its mission of delay was well-nigh accomplished, and a further reason for its departure was provided by the increasing successes of the 114th Regiment in the northern part of Bhamo. By 13 December this unit had penetrated the northern defenses and was cutting its way into the central part of Bhamo.19

At this point, Chinese techniques of war intervened to change what might have been the inevitable end of the story, a heroic suicidal dash by the Bhamo garrison on the machine guns of the besiegers, the so-called banzai charge that had been the final episode for so many Japanese garrisons before. American liaison officers with the Chinese formed the impression that a co-ordinated attack by the Chinese had been planned and ordered for 15 December.20

On the night of the 14th the Japanese in the garrison tried to fire off all their ammunition. Then they moved out into the river bed of the Irrawaddy and charged the Chinese lines along the river at daybreak. Taking advantage of the early morning mists, they moved through the Chinese lines to safety. As soon as the garrison was clear, the Japanese word for "success" was broadcast to the waiting Yamazaki Detachment, which promptly began to disengage. The Japanese claim that 950 of the garrison's 1,200 men made their way safely to Namhkam. American records support the claim of a successful withdrawal. After the war, the Chinese chronicler, Dr. Ho Yung-chi, former vice-commander of the 38th, stated that the Bhamo garrison was allowed by General Sun Li-jen to escape, only to be annihilated later. However, the agreement between the Japanese and American accounts, plus the fact that the American liaison officers with the 38th Division were told

nothing either of Sun's order to let the Japanese garrison through his lines or of any later annihilation of 950 Japanese, suggests that there are some flaws in the Chinese account.21

If to Western minds the reasoning which permitted the Japanese garrison of Bhamo to live to fight another day was difficult to follow, a Western observer had to admit that the performance of the Chinese 38th Division at Bhamo compared most favorably with that of the combined Chinese and American forces at Myitkyina six months before. That within thirty days the Chinese 114th Regiment should have hacked a way through defenses the Japanese had been six months preparing and have accomplished the feat with artillery and air support that was slight in comparison with that at the disposal of Allied forces elsewhere reflected the greatest credit on the unit and its commander.

Last Days of the Burma Blockade

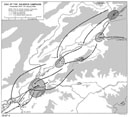

After the fall of Bhamo, the Chinese Army in India and the Chinese Yunnan divisions, or Y-Force, were within fifty air miles of each other. This narrow strip of rugged, highly defensible terrain was the last Japanese block across the road to China. (Map 7)

The Chinese Army in India had before it a march of twenty miles south-southeast over fairly level country; then it met the escarpment that was the western edge of the great plateau through which the Shweli and Salween Rivers had cut their valleys, the great plateau on which, far to the east, was China's Yunnan Province, Kunming, and the Hump terminals. The road the Chinese took was an extension of the Myitkyina-Bhamo road, one-way and fair-weather but leading directly to the old Burma Road. All the road needed was metaling and widening and it would be ready for heavy traffic as the easternmost end of the Ledo Road. The road met the hills about twenty miles south of Bhamo. Crossing a series of ridges it entered the Shweli valley. It then swung northeast for about thirty miles and linked with the old Burma Road at Mong Yu. East of the Shweli valley, over fifteen miles of 5,000-foot hills, was the Burma Road.

Therefore, after the fall of Bhamo, the task facing the Allies in north Burma was to clear the 33d Army with its approximately 19,500 Japanese from the remaining fifty-mile stretch that lay between the two Chinese armies.

Map 7

Opening the Road to China

The positions the Japanese held in the Shweli valley from Namhkam to Wanting could have been most formidable. Namhkam, for example, had originally been fortified with the expectation that the whole of the 18th Division would hold it. However, the 33d Army's mission was only to delay the Chinese while the decisive battle was fought out around Mandalay; there was no thought of fighting to a finish and the 33d organized itself for combat accordingly. The Japanese positions in the vicinity of the valley covered the Burma Road, the main avenue of approach to Mandalay from the northeast. The bulk of the Japanese forces was deployed in the Wanting-Mong Yu area facing the Y-Force. The strongly fortified Wanting was held by the 56th Division, and ten miles to the rear along the Burma Road at Mong Yu was the 168th Infantry Regiment of the 49th Division, Colonel Yoshida. Thirty miles to the southwest of Wanting the Yamazaki Detachment, 3,000 strong, manned the Namhkam defenses astride the route of advance of the Chinese New First Army, thus protecting the left and the rear of the main body of Japanese troops in the Wanting-Mong Yu area. The 4th Infantry Regiment, 2d Division, Colonel Ichikari, located at Namhpakka on the Burma Road near its intersection with the road leading to Namhkam, was in a good position to be used as a tactical reserve along either of the roads. Thirty-third Army had expected that the Ichikari and Yoshida regiments would be transferred to the Mandalay area and the Japanese intended to keep them in reserve, but the Chinese pressure forced their commitment.22

As of 17 December NCAC headquarters believed, and correctly, that in the Tonkwa-Mongmit area, the center of the Japanese position in north Burma, they faced a strong force of the 18th Division. At Namhkam, NCAC estimated there were 2,500 Japanese, and from Namhpakka to the north edge of the Shweli valley, 2,500 more. In the north end of the valley, around Wanting, NCAC placed the 56th itself. A week later NCAC's G-2, Col. Joseph W. Stilwell, Jr., estimated that only delaying action and minor counterattacks were to be expected from the Japanese.23

When the Chinese 22d Division was recalled to China, in mid-December, General Sultan changed his plans and regrouped his forces. His original thought had been to send the 22d Division wide to the south and then east to place it across the old Burma Road in the Namhpakka area. This would cut off almost the whole of the 33d Army to the north and make inevitable its withdrawal, which in turn would clear the way for the Ledo Road to be linked with the Burma Road. In so planning, he was aware of the possibility that some Chinese divisions might be recalled to China and arranged his dispositions accordingly. He hoped that his forces might swing east like a giant gate whose southernmost edge would hit Lashio, but if he lost some

of his Chinese troops then he planned to compensate by shortening his gate and making a shallower swing to the east. Across the Allied line from west to east Sultan's new orders directed the following moves: (See Map 7.)

The British 36th Division would move east of the Irrawaddy, then southeast via Mongmit to cut the old Burma Road in the Kyaukme-Hsipaw area, well south of Lashio.

The 5332d Brigade (MARS Task Force) would make a most difficult march across hill country to the Mong Wi area, then cut the Burma Road near Hosi. Essentially, this was the mission once contemplated for the 22d Division.

The Chinese 50th Division, which had been following the British 36th Division down the Railway Corridor, would move just to the east of that unit, cross the Shweli River near Molo, and then move southeast to take Lashio. It thus moved into the area formerly occupied by elements of MARS Task Force.

The Chinese New First Army would occupy the upper Shweli valley from Namhkam to Wanting and reopen the road to China.24

The earliest action in the drive south from Bhamo to link up with the Y-Force and clear the road fell to the Chinese 30th Division. While the 38th had been besieging Bhamo, the 30th had been sent past it; the 30th was the division that had fought the Yamazaki Detachment at Namyu when the latter sought to relieve Bhamo. General Sun Li-jen, army commander, now ordered the 90th Regiment, 30th Division, to move straight down the road toward Namhkam. The 88th and 89th Regiments were sent on a shallow envelopment south of the road, to come up on Namhkam from that direction. The 38th Division was used for wide envelopments to either side of the 30th Division, and one of its regiments was kept in army reserve.25

After the heavy fighting of mid-December, the 30th Division did not find the Japanese to its front intent on anything more than light delaying action. The stage was set for a swift advance into the Shweli valley, but the commander of the 90th Regiment was not so inclined and, as he had the center of the Chinese line, the flanks delayed accordingly. His repeated failures to advance, and his practice of abandoning supplies and then requesting more by airdrop, were regarded by the American liaison officers as having wasted two weeks after the action at Namyu; his relief was arranged in early January. The new regimental commander, Colonel Wang, was energetic and a sound tactician; the regiment's performance improved at once.26

The 90th Regiment now moved with more speed, and soon reached the

hill dominating the southwestern entrance to Shweli valley. The term valley as applied here refers to a stretch of flat ground about 25 miles long and from 4 to 6 miles wide carved from the mountains by the Shweli River and its tributaries between Mu-se and Namhkam. The floor of the valley, 2,400 feet above sea level, is dotted with villages. The existing road, whose trace the engineers planned to follow, closely hugged the hills forming the southeastern edge of the valley. Namhkam was built along the road near the southwestern end of the valley and its immediate approaches were dominated by a hill mass abutting the Bhamo road between the river and its small tributary to the north.

Facing this terrain, the Chinese chose to circle around the southwestern end of the valley with the 90th Regiment, while the 112th Regiment was ordered to move directly across the valley on Namhkam. Units of the regiment began crossing the Shweli on 5 January 1945; the whole regiment was across in fifty hours. The regiment now came swinging around the southeast corner of the valley and up the eastern side of Namhkam. Meanwhile, the 88th Regiment had entered the valley along the road and cut across the little plain directly toward Namhkam.

Namhkam itself was occupied on 16 January by the 2d Battalion of the 90th. Only a few shots marked the change in ownership, and two Japanese were killed. Inspecting the settlement, the Chinese realized that the Japanese had not planned to stand there. So there was no dramatic battle. The significance lay in that the Japanese had been pushed away from the lower end of the Shweli valley. Once the valley was in Allied hands, the road to China was open, and on 15 January the Japanese 33d Army, which attached little significance now to blockading China, was slowly pulling back off the trace of the road to China.27

Since the 38th Division had been engaged at Bhamo while the 30th Division had bypassed the fighting there and gone on toward the Shweli valley, its regiments were behind the 30th and, in effect, had to follow it in column before they could swing wide to envelop the Shweli valley. The 112th Regiment had been pulled out of the lines at Bhamo just before the city fell and sent toward the Shweli valley along trails running through the hills north of the Bhamo road. There was little contact with the Japanese, and as the 112th moved along it stopped on Chinese soil, so close is the Bhamo area to China. This made the 38th the first Chinese unit to fight its way back to Chinese soil. Moving steadily on, the regiment was in the Loiwing area on 6 January 1945. In 1941 Loiwing had been the site of the Central Aircraft Manufacturing Company plant. In 1942 Chennault and the American Volunteer Group had operated from the Loiwing field for several

BURMESE IDOL IN NAMHKAM. American and Chinese soldiers are from the Northern Combat Area Command.months. Now, it was back in Allied hands. Patrolling from the Loiwing area across the Shweli to Namhkam, the 112th concluded that the road to Namhkam was open. It requested permission to take the town, but was held back until the 30th Division occupied it.28

The 114th Regiment, which had so distinguished itself at Bhamo, was given the mission of swinging wide around the southern end of the Shweli valley. Because of the casualties the 114th had taken at Bhamo it had to be reinforced with the 1st Battalion of the 113th. The mission it received was to be a severe test of its marching powers, for on reaching the south end of the Shweli valley it was to ford the Shweli, move south and east through the hills on the right flank of the 89th Regiment as the latter moved on Namhkam, then continue its march to cut the Namhkam-Namhpakka trail about midway. At the mid-point, the village of Loi-lawn, it would be about

TWO SOLDIERS. An American-trained and -equipped soldier of the Chinese Army in India (left), compares lots with a Chinese Expeditionary Force soldier at Mu-se, Burma.seven miles from the old Burma Road, which was the line of communications to the Japanese 56th Division in the Wanting area. Crossing the Shweli on 10 January, it reached Ta-kawn on the 16th. Making this the regimental base with a garrison and air supply facilities, Col. Peng Ko-li sent two battalions off to cut the Namhkam-Namhpakka trail. The Japanese resisted stubbornly, and not until the 19th were the Chinese across the trail.29

With the southern end of the Shweli valley firmly in Chinese hands by 17 January, General Sun issued his next orders, which called for the 112th and 113th Regiments to move up the Shweli valley toward Wanting and secure the trace of the Ledo Road. At this point the conceptions of the battle held by NCAC and 33d Army were very much at odds. NCAC saw its men as fighting their way up the valley in a northeasterly direction. The

Japanese saw themselves as falling slowly back from the Shweli under pressure from the northwest. Actually, the only pressure from the northwest was that of the 30th Division and the MARS Task Force, which after rounding the Namhkam corner were moving southward toward the Burma Road. In the northern two thirds of the Shweli valley, the 38th Division's flank guards, as they drove northeast, were brushing across the Japanese rear guards, which were falling back to the southeast and attempting to cover the Burma Road, their line of communications and avenue of retreat.

Such being the case, the 38th not surprisingly met little resistance as it drove up the Shweli valley. The 56th Division was holding strongly only at Wanting, where the road up the valley met the Burma Road, and not until the 38th Division approached Wanting did Japanese resistance stiffen.

First contact with the Japanese came at Panghkam, a village near the northern exit of the valley. The 113th stayed in the valley, and the 112th was sent wide into the hills to the right of the road near Se-lan. Japanese resistance was of the rear-guard variety; the 113th was only slowed, not stopped. As it approached Mu-se, the exit of the valley, its leading elements on 20 January joined with Chinese troops of the Yunnan divisions.30 These men had entered the Shweli valley by enveloping its northern end, much as Sun Li-jen's troops had enveloped the southern, then driving directly across to the southern side. The trace of the road was not yet open, but the presence of the Yunnan troops meant formal opening was only a matter of days.

The End of the Salween Campaign

While the Chinese Army in India had been moving on and then encircling Bhamo, the battered divisions of General Wei Li-huang's Chinese Expeditionary Force had been trying to recover from the blows inflicted on them by the September Japanese counteroffensive, which the Chinese had manfully stemmed.31 At the end of the battle, both sides were exhausted, but the Chinese could claim the advantage. They had kept the Japanese from reoccupying the terrain about Teng-chung and Ping-ka, which controlled passes into Burma north and south of the Burma Road, and they had held on to Sung Shan, from which Japanese artillery had once controlled the ascent of the Burma Road from the Salween gorge. On the Burma Road itself, the Chinese, with the survivors of seven divisions, were in a semicircle to the east of Lung-ling.

As October began, American liaison officers with the Chinese saw traffic movements and demolitions within the Japanese lines that convinced them,

and correctly, that the Japanese were thinning their lines, that only rear-guard action was contemplated.32

The Chinese of XI Group Army completed their preparations for the next attack, and on 29 October it began. Thirty-seven P-40's from the Fourteenth Air Force flew close support for the Chinese 200th Division, a veteran of the 1942 campaign, which led the assault. South and west of Lung-ling, elements of the Chinese 200th swung around to attack positions along the Burma Road behind Lung-ling. Meanwhile, two divisions of the 71st Army put heavy pressure on the Japanese garrison, with artillery support up to 1,700 rounds and 30-40 air sorties per day. Late on 3 November the last Japanese left Lung-ling and at 2300 the Honorable 1st Division moved through the gutted center of the town.33(Map 8)

A pause followed which thoroughly disturbed General Dorn, the chief of the Y-Force Operations Staff advising General Wei. Dorn saw no reason why the Chinese should not follow closely on the Japanese rear guards, feared that the Chinese were delaying, and asked Wedemeyer to intervene with the Generalissimo. Wedemeyer agreed, and pointed out to the Generalissimo that it was important to finish the campaign and free the Y-Force for service in China. On 9 November the Generalissimo agreed to give the necessary orders.

In addition to advising on strategy and tactics and furnishing air support, the American forces gave medical aid. From the opening of the campaign in May 1944 to November they treated 9,428 Chinese, of whom only 492 died. Many wounded never reached an American hospital because of the rough terrain, but even so this was the best medical aid Chinese forces in China had yet enjoyed.

Receiving the Generalissimo's orders to advance, General Wei sent his XI Group Army (53d, 2d, 71st, 6th Armies) against Mang-shih, the 56th Division's former headquarters. One army moved through the hills on the north side of the Burma Road, and two on the south, while the 71st came down the road itself. Having strict orders to avoid any decisive battle, the 56th Division contended itself with demolitions, burning the rice harvest, and delaying the Chinese with rear-guard actions. Casualties were light among the Chinese as they advanced through Mang-shih on 20 November. At this point the Chinese were about seventy miles away from Namhkam in the Shweli valley. Mang-shih was a valuable prize because of its airstrip. Speedily repaired, it permitted the C-46's of the 27th Troop Carrier Squadron to land supplies, a much more economical and satisfactory means than air-dropping.34

Map 8

End of the Salween Campaign

3 November 1944-27 January 1945

Meanwhile, the Fourteenth Air Force continued to harass the retreating Japanese, bombing all bridges and likely Japanese billets. The Japanese were careful to stay clear of the Burma Road in daylight, but contacts with their rear guards gave the P-40's opportunity to demonstrate close air support.

By this time Wei had a solution to his tactical problems. One army moved along each of the ridges that paralleled the road, and the rest of his forces came straight down the road. If the Japanese, as at the divide between Mang-shih and the next town twenty-four miles away, Che-fang, attempted a delaying action with a small force, the wings of Wei's force simply outflanked them and forced them back. If the Japanese, as seemed likely to be the case at Wanting, attempted a stronger stand, then Wei was advancing in a formation well adapted to rapid deployment and encirclement. Che-fang fell on 1 December, and Wanting was the next target.

Lying as it does at the northeastern exit of the Shweli valley, on the Burma Road, Wanting had to be taken. Moreover, pressure on Wanting would make it difficult for the Japanese to transfer units from that front to meet the NCAC troops at the southwestern end of the Shweli valley.

Not for another thirty days did the Chinese resume their offensive down the Burma Road. Asked by Y-Force Operations Staff to send out strong patrols at least, the Chinese were willing, but ordered their patrols to stay out of Wanting. The Chinese unwillingness to advance down the Burma Road and end the blockade of China as quickly as possible, at a time when Wedemeyer was making every effort to bring aid to China, moved the latter to make very strong representations to the Generalissimo. After describing the situation around Wanting, Wedemeyer wrote:

It is a policy of the China Theater not to give aid to those who will not advance; therefore, no air support has been given to these divisions nor to the others in that section who, apparently having similar instructions, cannot advance. The Chief of Staff [General Ho] has been promised renewed efforts when he puts into effect plans which are now being developed to take Wanting. His earlier plans to send two regiments as patrols into Wanting did not materialize.

I feel certain that if you will issue orders to these C.E.F. [Chinese Expeditionary Force] forces to take Wanting, they have the ability to do so in a short time. I certainly will provide all the air support possible which should greatly facilitate the capture of the objective.35

Then, on 15 December, Bhamo was evacuated by the Japanese. General Wei may have wanted to delay his attack until he could be sure that the NCAC forces would not be delayed by another siege like that of Myitkyina.

Wei's divisions were now far understrength, since replacements had not been supplied, and lacked 170,000 men of their prescribed strength.36

As part of his swing around China Theater, Wedemeyer visited Wei on 20 December. The American commander urged Wei to resume the offensive, to link his forces with Sultan's because the east China situation demanded everyone's aid. Apparently, Wei's circumstances were changing, because in late December the Y-Force began its last battle.

The first Chinese attack was made by the 2d Army on the Japanese right flank, in the area of Wanting. Initially, it went very well. The Chinese 9th Division on 3 January broke through to the village streets, finally reaching the Japanese artillery positions. The Japanese rallied, and there was bitter hand-to-hand fighting--"pistols, clubs, and bayonets"--according to the Japanese account. That night the Japanese counterattacked successfully and drove out the Chinese.

Wei then shifted his attack to the Japanese left flank, which lay along the Shweli River. The Chinese succeeded in establishing a bridgehead but could not hold it against Japanese counterattacks by two regiments, and the attempt failed. A pause of a week or so followed.

The Japanese defense of Wanting had been successful, but while the 56th Division had been fighting in that area, Sultan's NCAC forces in the Namhkam area, including the MARS Task Force, had begun moving eastward toward the Burma Road. If they succeeded in blocking the Burma Road, the 56th Division's position obviously would be compromised. So the problem the Japanese faced was to know how long they could afford to fight at Wanting before the exit slammed shut. As noted above, the MARS Task Force had been dispatched by Sultan to block the Burma Road, and by 17 January it was clashing with Japanese outposts adjacent to it. Weighing all these factors, the 56th Division in mid-January estimated it could hold its present positions about one week more. The 33d Army could not afford to cut things too fine, and so the 56th began to shorten its perimeter as it prepared to withdraw south down the Burma Road while time remained.

Since attempts at enveloping the Japanese position had been successfully countered by the alert defenders, the American liaison section with XI Group Army, Col. John H. Stodter commanding, suggested that Wei try a surprise attack on the center, which seemed to be lightly held. American liaison officers took an active part in the planning. After the war, as he looked back with satisfaction on the careful co-ordination of air, artillery, and infantry weapons that distinguished this attack from many of its unsuccessful predecessors along the Salween, Stodter thought it the "best coordinated" he

had seen to that time in the Y-Force. From his observation post, Stodter watched the Chinese infantry attack on 19 January and climb up the dominant local peak, the Hwei Lung Shan. Chinese artillery, mortar, and machine gun fire pounded the Japanese trenches until the last moment, then the Chinese infantry attacked with grenade and bayonet. The attack succeeded, Japanese counterattacks failed, and the Japanese hold on Wanting was no longer firm.37

On 20 January elements of the Chinese 9th Division found Wanting empty. Later in that day patrols from Wei's army met other patrols from Sultan's Chinese divisions. The long Salween campaign was drawing to a victorious close; the road to China was almost open.

The final work in opening the Burma Road would have to be done by the Chinese Army in India. On 22 January the Generalissimo ordered the Chinese Expeditionary Force to concentrate north of the Sino-Burmese border. He informed his commanders that remaining Japanese resistance would be cleared away by the Chinese Army in India. Two days later General Wei ended his offensive, and ordered his units to stay in place until relieved by one of Sultan's. The Salween campaign was thus formally ended 24 January 1945.

On the vast panorama of the world conflict the Salween campaign did not loom very large to the Western world. But the Chinese had succeeded in reoccupying 24,000 square miles of Chinese territory. It was the first time in the history of Sino-Japanese relations that the Chinese forces had driven Japanese troops from an area the Japanese wanted to hold. To this effort China had contributed initially perhaps 72,000 troops and in the fall of 1944 some 8,000 to 10,000 replacements, plus the elite 200th Division. The United States had given 244 75-mm. pack howitzers, 189 37-mm. antitank guns, and infantry weapons, plus sufficient ammunition. American instructors and liaison officers had sought to assist the Chinese in their conduct of operations. The Fourteenth Air Force had been ordered to draw heavily on its small resources to support the operation. The Japanese had initially faced Wei's men with 11,000 soldiers and thirty-six cannon. For their fall offensive they had reinforced the much-reduced original garrison with 9,000 more soldiers from the 2d and 49th Divisions.

The military significance of Wei's victory lay in the trucks and artillery which now would move into China, and in the three elite divisions released for service there. For the future, the Salween campaign demonstrated that, given artillery and heavy weapons plus technical advice, Chinese troops, if enjoying numerical superiority of five to one or better, could defeat the forces

of the Great Powers. Observing the campaign, the American liaison officers had concluded that technical errors by the Chinese reduced the combat efficiency of the Chinese forces. Failure to bypass isolated Japanese units; inability to co-ordinate infantry and artillery; faulty maintenance of equipment and poor ammunition discipline--all tended to offset the valor and hardihood of the Chinese soldier. None of the practices was beyond correction. As the Chinese improved, they would require less in the way of numbers.38

Opening the Ledo Road

In the period between the split of the CBI Theater in October 1944 and the fall of Bhamo on 15 December, the Ledo Road engineers under General Pick brought the survey of the Ledo Road from a point just below and east of Kamaing, 211 miles from Ledo, to a juncture with the Myitkyina-Bhamo road. The Ledo Road was to bypass Myitkyina, for there was no point to running heavy traffic through an inhabited place, and Myitkyina's supply needs could be served by an access road. Metaling and grading were complete almost to Mogaung. The Mogaung River had been bridged near Kamaing, and a temporary bridge placed across the Irrawaddy. Tonnage carried on the road for use within Burma was steadily rising. In early October it had carried 275 tons a day; by the latter part of the month the rate was twice that.39 Immediately after Bhamo's capture, the advance headquarters of the road engineers was moved to that town. A combat supply road was made from Mogaung, below Myitkyina, to a point just ten miles west of Namhkam.

Progress during December was steady, swift, and uneventful because once the roadbuilders reached the Myitkyina area of north Burma only routine engineering remained. In mid-January the Ledo Road was linked with the Myitkyina-Bhamo road, at a point 271 miles from Ledo. The Myitkyina-Bhamo road was being metaled, and, significant of the state of the link to China, the first truck convoy was poised at Ledo ready to drive to Kunming. The road to China was complete, as far as the engineers were concerned. Beginning the traffic flow now depended on driving away the Japanese. A four-inch pipeline paralleled the road as far as Bhamo, where the intent was to send the line cross country to China, rather than along the next stretch of road. The mission of clearing the Japanese rear guards from the last stretch of the road trace was given to the 112th and 113th Regiments of the Chinese 38th Division, with the 113th moving up the valley along the existing road

PONTON BRIDGE OVER THE IRRAWADDY RIVER was an important link in the Ledo Road.from Panghkam and the 112th going through the hills. By 23 January the 112th had reached a point in the hills south of the valley road from which it could, through a gap in the hills, see the Shweli valley road behind the Japanese lines but at a range too great to bring fire to bear. The regiment halted that afternoon and formed its defenses for the night. The precaution was wise, for that afternoon and evening several Japanese detachments withdrawing from the valley area found the 112th across their projected routes and at once tried to fight their way through. There was brisk fighting, and sixty-seven dead Japanese were later buried around the regiment's positions.

Meanwhile, the first convoy had closed on the Namhkam area and was waiting for the all-clear signal. The road stretch from Namhkam to the northeast was being efficiently interdicted by fire from a Japanese 150-mm. howitzer. The convoy was heavily laden with representatives of the press; there would be a great to-do if a 150-mm. shell burst among them on a section of road that the Army had designated as clear, and so the convoy was

held up several days at Namhkam while NCAC pressed the Chinese to open the road and also tried to silence the 150-mm. howitzer by counterbattery.

An artillery observation craft was sent aloft and after some time managed to locate the Japanese howitzer. Several rounds were fired; the Japanese finally displaced the howitzer to a safer spot.40

To expedite the clearing of the road, the NCAC chief of staff, Brig. Gen. Robert M. Cannon, conferred with the Chinese commander, General Sun Li-jen, on 24 January and received General Sun's promise that the road would be open on 27 January. Unknown to the two Allied officers, the Japanese began withdrawing the 56th Division from the Wanting area on 23 January, beginning with their casualties and ammunition.41 Reflecting the decisions of the conference, the 113th Regiment moved forward on the 25th, and by the night of the 26th there were only five miles of Japanese-held territory between the two Chinese armies.

On the night of the 26th plans were made for an attack by armor and infantry, supported by artillery, to clear the last five miles. Careful co-ordination was needed lest the attack carry on into the Y-Force, beyond, and conferences between U.S. liaison officers from Y-Force and NCAC sought to arrange it. The attack moved off the morning of the 27th, with the tanks overrunning the little village of Pinghai, the last known enemy position. It fell without opposition. Meanwhile, an air observer reported that he saw troops in blue uniforms, undoubtedly Y-Force soldiers, in the area where the Shweli valley road joined with the Burma Road. A message was sent out canceling all artillery fire. Unfortunately, soldiers of the 38th opened small arms fire on the Y-Force troops.

At this point, Brig. Gen. George W. Sliney, who had been an artillery officer in the First Burma Campaign, intervened to halt what might have become an ugly incident. Fearlessly exposing himself to the Chinese bullets, he walked across the line of fire and forced it to stop. Sliney then walked over to the Y-Force lines. So ended the blockade of China.

Soon after, some tanks with the 38th mistakenly fired on Y-Force men. Their artillery retaliated. Only prompt action by General Sun Li-jen and the liaison officers with the 112th straightened out the affair. With this misunderstanding ended, the road to China was open, and the first convoy was ready to roll. The Ledo Road, built at an estimated cost of $148,000,000, was open.42

The confusion that attended the meeting between Y-Force and the

CHINESE COOLIES LEVELING A ROADBED for the Teng-chung cutoff route to Kunming.

Chinese Army in India was only a reflection of the greater confusion that surrounded the actual declaration that the road to China was open and the blockade broken. The several headquarters involved in the operation were aware of the public relations aspect of the feat; there were sixty-five press and public relations people in the first convoy as one indication of it--more reporters than there were guards.

The inaugural convoy had departed from Ledo on 12 January. Its trucks and towed artillery, with Negro and Chinese drivers, the latter added for ceremonial reasons, reached Myitkyina on the 15th, and then had to wait there until the 23d because the Japanese still interfered with traffic past Namhkam. On the night of the 22d, Lt. Gen. Daniel I. Sultan, India-Burma Theater commander, made some rough calculations of space and time, and announced that the road was open. Probably he expected the Japanese to be gone by the time the convoy reached the combat area. Next morning the caravan got under way again. It reached Namhkam without incident, and then confusion began.

The newsmen and public relations officers were surprised to learn on the 24th that the British Broadcasting Corporation had just announced the arrival of the first truck convoy at Kunming, China, via Teng-chung, on 20 January. India-Burma and China Theater authorities had long known that a rough trail, capable of improvement, linked Myitkyina and Kunming via Teng-chung. There had been considerable discussion of the respective merits of the Bhamo and Teng-chung routes, with General Pick firm for the Bhamo trace. The Chinese liked the idea of a Teng-chung route, and had advocated the Teng-chung cutoff as an alternative to and a supplement of the Bhamo route. Their laborers to the number of 20,000 were put to work on the stretch beyond Teng-chung, beginning 29 September 1944 and were supported by the small force of American engineers under Colonel Seedlock who had been assisting in reconstructing the Chinese portion of the Burma Road. In less than sixty days, 145 miles were cleared.43

On 20 January 1945, two trucks and an 11-ton wrecker commanded by Lt. Hugh A. Pock of Stillwater, Oklahoma, arrived at Kunming after a sixteen-day trip from Myitkyina. At one point, at a precipitous pass, the back wheels of the lead truck had slid out over empty space; the vehicle had to be winched back. At another point Lieutenant Pock had to halt his little convoy while one of Seedlock's bulldozers cleared a path. But this was minor compared to the fact that a truck convoy had reached China.44 No more than sixty-five vehicles crossed into China via Teng-chung, for the route was a rough one, and not paralleled by a pipeline as was the route via

Bhamo. The impact of the news was immediate. As a result of some of the announcements that followed, General Merrill radioed Sultan:

A Reuter's report has been published and broadcast to the effect that convoys from India have been reported by Chinese sources to have crossed overland from India to China via Teng-chung. The Supreme Allied Commander is quoted as radioing Churchill and Roosevelt: "In accordance with orders you gave me at Quebec, the road to China is opened."

Wheeler's PRO [Public Relations Officer] has sent to Washington a blurb saying that the "plan drawn up by Lt. Gen. Raymond A. Wheeler two years ago is now about to pay off."

The Chinese censors have scooped your correspondents, but events in Europe and the Pacific are dwarfing the story. I recommend you take no action except to get your convoy across the border fast.45

On the morning of the 28th, the official inaugural convoy from India-Burma Theater resumed the often-interrupted journey. There was a two-hour ceremony at Mu-se, and then, a few miles beyond, a road junction with a macadam road. As the trucks swung out onto it realization flashed down the line that they were at last on the Burma Road and in China. Two days later, as the convoy crossed the Salween, an air raid alarm brought a flurry of excitement. Then came the long drive through Yunnan Province to Kunming, through dry, hilly, brown land, a contrast to the green and blue of the Burmese hills. The night of 3 February the convoy bivouacked at the lake Tien Chih, and next morning Chinese drivers took over for the ceremonial entry.

On 4 February the line of 6 x 6 trucks and jeeps, some of the prime movers towing 105-mm. and 75-mm. howitzers, entered Kunming. General Pick led the parade, standing erect in his jeep. Firecrackers crackled and children screamed; American missionary nuns waved greetings, and Chinese bands added their din. That night Governor Lung Yun of Yunnan gave a banquet which was graced by the presence of an American operatic star, Lily Pons, and her husband, a widely known conductor, Andre Kostelanetz. The occasion had its ironic side, unknown to the Americans as they rejoiced in the completion of the engineering feat; for, if General Okamura's memory is to be trusted, Lung Yun corresponded with him throughout the war.46

Shortly after the road was opened, the Generalissimo suggested that it be renamed the Stilwell Road. The idea received general approval, and so the man who was primarily a tactician and troop trainer, whose mission and greatest interest was the reshaping of the Chinese Army into an efficient force, had his name applied to one of the great engineering feats of history, and was indelibly associated with it in the public mind. The soldiers called it either the Ledo Road or "Pick's Pike."47

Table of Contents ** Previous Chapter (3) * Next Chapter (5)

Footnotes

1. History of 5332d, Ch. III.

2. History of Combat in the India-Burma Theater, 25 Oct 44-15 Jun 45, p. 5. OCMH. (Hereafter, IBT Combat History.)

3. (1) IBT Combat History, p. 6, and facing Japanese map. (2) Bhamo's provisions would last only until the end of December. (3) Ltr, Hq NCAC, 27 Nov 44, sub: Translation of Captured Documents. Folder, Complete Translations, Nos. 151-250, NCAC files, KCRC. (4) Ltr, Hq New First Army to CG CAI, Dec 44, sub: Captured Enemy Documents. NCAC files, KCRC.

4. (1) IBT Combat History, p. 8. (2) Under interrogation, one enemy prisoner stated that at first the Japanese were told they must fight to the death, but later that if they fought well they would be allowed to evacuate. Superior Pvt Rokuro Wada, 12 Dec 44. Folder 62J, 411-420, NCAC files, KCRC.

5. (1) IBT Combat History, pp. 7-9. (2) Statement of Pvt Wada cited n. 4(2).

6. IBT Combat History, p. 11.

7. Capt. Erle L. Stewart, Asst G-2 NCAC, The Japanese Defense of Bhamo, 3 Mar 45. OCMH. (Hereafter, The Japanese Defense of Bhamo.) This study has an excellent aerial photograph as its Appendix VII.

8. NCAC History, II, 201-03.

9. (1) The Japanese Defense of Bhamo. (2) Japanese Officers' Comments on draft MS.

10. NCAC History, II, 201-03.

11. IBT Combat History, p. 13.

12. NCAC History, II, 203-04.

13. The Japanese Defense of Bhamo.

14. Japanese Study 148, pp. 40-41.

15. NCAC History, II, 253-57.

16. (1) NCAC History, II, 258, 259. (2) Japanese Study 148, App. D, The Yamazaki Detachment in the Battle at Namyu.

17. Japanese Study 148.

18. Japanese Study 148, p. 42.

19. (1) Japanese Study 148. (2) Japanese PW Statements. Folder 62J, 411-420, Japanese Documents, NCAC files, KCRC. (3) NCAC History, II, 204.

20. The American combat narratives, prepared in 1945 from sources at the disposal of NCAC, such as liaison officers' reports, Daily Operational and Intelligence Summaries, and the like, refer to the proposed attack of 15 December. There is no hint that the American liaison officers knew Sun had ordered that the Japanese were to be allowed to escape.

21. (1) Japanese Study 91 states the Bhamo garrison made good its escape and rejoined the 2d Division. (2) Japanese prisoners of war taken later in December 1944 state that 400 to 600 Japanese evacuated Bhamo. Folder 62J, 411-420, Japanese Documents, NCAC files, KCRC. (3) NCAC History, II, 205, says that an attempt was made to intercept the Japanese but failed because reserves were too far away. (4) Dr. Ho Yung-chi, The Big Circle (New York: The Exposition Press, 1948.) p. 130.

22. Japanese Study 148, pp. 43-44.

23. NCAC G-2 Rpts, 17, 24 Dec 44. NCAC G-2 files, KCRC.

24. History of IBT, I, 137-39.

25. History of IBT, I, 182.

26. (1) History of NCAC, II, 260-61. (2) The Japanese remarked on the slow progress of the Chinese advance, Japanese Study 148, p. 45.

27. History of NCAC, II, 261-62.

28. History of NCAC, II, 272-74.

29. History of NCAC, II, 275-76.

30. Ibid.

31. For a description of the September fighting, see Stilwell's Command Problems, Chapter XI.

32. (1) Y-FOS Journal, KCRC. (2) Japanese Studies 93 and 148. This section, unless otherwise noted, is based on these sources.

33. Comments of Col. John H. Stodter on draft MS of this volume.

34. See Stilwell's Command Problems, Chapter III, for a discussion of the several techniques of air supply.

35. Memo 275, Wedemeyer for Generalissimo, 10 Dec 44. Bk 16, ACW Corresp with Chinese.

36. Memo 304, McClure for Generalissimo, 20 Dec 44. Bk 16, ACW Corresp with Chinese. This memorandum describes Wedemeyer as being disturbed over the replacement problem in the Y-Force.

37. Stodter comments on draft MS. Elsewhere in his comments, Stodter remarks that Chinese noncommissioned officers and junior officers, though inexperienced, appeared brave and intelligent, while the Chinese private won the affectionate regard of those Americans who served with him.

38. Liaison officer reports in Y-FOS files, Kansas City Records Center, contain many comments on Chinese tactics and techniques, 1943-45.

39. History of IBT, I, 172-73.

40. NCAC History, III, 282, hints the piece was destroyed, but Lt. Col. Trevor N. Dupuy, who was in the area, states it was merely forced to move.

41. Japanese Study 148, p. 48.

42. (1) NCAC History, III, 283-85. (2) Dupuy witnessed Sliney's act. Dupuy comments on draft MS. (3) Stodter comments on draft MS. (4) Memo, Engr Hist Div, Office, Chief of Engrs, 25 Mar 53. OCMH.

43. (1) Ltr, Col Seedlock to Romanus, 21 Dec 50. OCMH. (2) Rpt, Board of Officers re Pipelines and Burma Road, Including Teng-chung Cutoff 31 Oct 45. CT 41, Dr 1, KCRC.

44. History of IBT, I, 188.

45. History of IBT, I, 189.

46. (1) History of IBT, I, 191-92. (2) Japanese Officers' Comments, Okamura, p. 6. OCMH.

47. Mountbatten Report, Pt. B, par. 393.