SALERNO LANDINGS

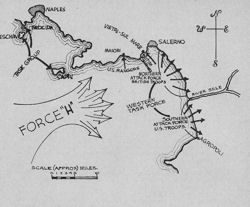

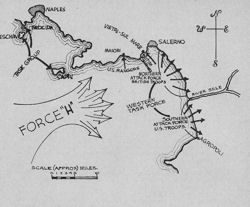

The Naval operations were composed of two main forces: the Western task Force and Force "H."

The Western Task Force was divided into two: the Northern Attack Force and the

Southern Attack Force.

Force "H" consisted of a large covering force of battle ships, aircraft carriers,

cruisers and destroyers.

Map by George Six]a, SP-(P)2C, in Magazine Shipmate, February, 1944.

--114--

Part II

LANDINGS OF SALERNO

STRONG GERMAN RESISTANCE DESPITE ITALIAN SURRENDER

When the Allies landed at Salerno, on September 9, 1943, the Germans were there

awaiting the invasion forces. This was not due to any prescience on Marshal Kesselring's part.

He knew that the beachhead at Salerno was at the effective limit of Allied

fighter range from Sicilian bases and had made plans accordingly. The result

was a bitter and bloody battle, which, as it happened, the Allies won only by

the skin of their teeth. The Italian battlefield was of our choosing.

But once the fighting in Italy began, the Germans gave every indication that

Italy was too great a strategic and political prize to be allowed to go by default.

The surrender of Marshal Badoglio's government, the day before, did not prevent

the Germans from offering strong resistance to our troops in the Salerno area of Italy.

LANDINGS ARE MADE IN HOTLY CONTESTED AREA

At about 0400, on September 9, units of the United States Fifth Army together

with British and Canadian forces, under the protection and cover of the Royal Navy

and the United States Navy, landed on the Italian mainland in the Naples area.

The landings were made along the rim of Salerno Bay, some forty miles southeast

of Naples. United States forces disembarked south of the Sele River, seventeen

miles south of Salerno. British units disembarked north of the river. Rangers

and Commandos also landed between Amalfi and Maiori, west of Salerno. Troops,

guns, and vehicles were disembarked according to schedule despite enemy air attacks

on the convoys. Movement inshore at some points was delayed by a large number of mines,

which had to be cleared by minesweepers, and on sane beaches considerable opposition

was encountered. Coast artillery also opposed the landings. In opposing the landings

around Salerno, the Germans had the advantage of strongly prepared positions

and artillery emplacements. Secretary of Navy Knox described the establishment

of the beachhead as the most hotly contested which landing American troops had

ever made. In addition to the prepared positions on the beaches, the Germans

were entrenched in hills overlooking the coastal plain area in which the fighting took place.

PRE-INVASION PREPARATIONS BY ALLIED AIR FORCES

For several weeks

before the Fifth Army invasion,, Allied air forces had pounded road and rail

communications in the Naples area. On the night before the invasion, the rail

yards at Battapaglia and Eboli were hit with a total of about 170 tons, and 160

tons were dropped on the roads leading to the beaches at Salerno. On the day of

the invasion and every day thereafter, Allied bombers of all types continued

their efforts to tie up the rail and road system supplying enemy troops in the

Naples area. Among the targets were Sapri, the Lagonegro-Auletta road, Potenza,

the Corletto-Auletta road, the Benevento-Ariano area, Formia, Mignano, and

Isernia. In contrast to Axis air activity oyer the Salerno bridgehead, fighter

opposition to these Allied attacks was light. Allied planes also continued to

attack enemy

--115--

U.S. COAST GUARDSMEN SWING AN ARMY TRUCK OVERSIDE AS THEIR COMBAT TRANSPORT LIES

OFF A BRIDGEHEAD ESTABLISHED AT PAESTERNUM

--116--

communications, troop movements, and gun positions in the southern part of Italy. No enemy

opposition was encountered in these operations.

COMBINED OPERATION

The Battle of

Salerno was a combined operation, in which the Allied armies gained their

final victory through the exceptionally heavy support given them by the Allied

Navies from the sea and in the air. The task of the Allied Navies did not end

with transporting the Army safely to its destination. The entire force had to be

covered against possible attack from surface vessels and submarines and most of

the fighter protection in the air had to be given by the Fleet Air Arm from

aircraft carriers at sea. The assault was ordered to be "pressed home,

regardless of loss or difficulty," and it was emphasized that the attack did not

end with the arrival of the assault wave and the capture of the beaches. It was

upon the rapid follow up of reserves and the swift landing of supplies by the

Allied Navies that the Army relied to sustain the attack and give it complete success.

THE JOSEPH T. DICKMAN AT SALERNO

ARRIVAL AT BEACHES IN GOOD WEATHER

On the morning of

September 9, the Joseph T. Dickman, commanded by Captain Richard J. Mauerman,

USCG, landed assault troops on the 2nd Battalion Combat Team, 142nd Infantry,

56th Division, U.S. Army and attached units, on Green Beach, Salerno Bay. In

all, there were 81 officers and 1,623 enlisted men in the Army group. Weather

conditions were excellent for lowering boats and ease of holding boats

alongside. Little seasickness occurred among the troops on the trip from ship to beach.

LOWERING OF BOATS COMPLETED IN ONE HOUR

Following the

ships ahead in to the transport area, the Dickman passed the submarine

beacon Shakespeare at 2333 on the 8th, at the departure point. At 0002 on

the 9th, the Dickman stopped and drifted in her designated transport area. An

LCS(S) boat, with a scout officer, was lowered into the water at 0020 and

departed for shore to locate Green Beach. The beach was found and marked as

planned without difficulty. The lowering of boats commenced at 0015 and was

completed in an hour, with the exception of two boats that were damaged.

However, the boat teams that should have been rail loaded in these two boats

were expeditiously loaded at the White net and arrived in the rendezvous area in

time to go in with their wave. (The two boats, in #1 starboard davit, upper and

lower inside cradles, were damaged and wedged in by the strong-back that fell

across the upper boat when the after davit arm dropped down, due to the breaking

of the wire cable. This davit was repaired and in working order prior to 1660 on

D plus 1 day). The third rail loading boat at #2 davit port side was delayed due

to the cable becoming jammed on the drum. This boat was loaded at Yellow net

port side. No delay at the rendezvous area was caused by this boat. Twenty-one

LCVP's and two DUKW's were pre-loaded with boat team equipment and rail loaded

with troops. Eleven LCVP's were pre-loaded with equipment and net loaded with personnel.

--117--

AT PAESTUM, SOUTH OF SALERNO, BULLDOZERS, AMPHIBIOUS "DUCK TRUCKS," AND OTHER HEAVY EQUIPMENT BEING UNLOADED

--118--

PC-625 LEADS

The primary

control vessel, PC-625, led the first three waves of boats from the

rendezvous area, passed the restricted area marker boat PC-542, and proceeded on

to the line of departure. All boats landed on the correct beach in excellent

line and well spaced, but were ten minutes late in the scheduled time. This

delay was due to the fact that the primary control boat was held up behind by

the minesweepers. When the ramps of the first wave were lowered and troops

crossed the beach, heavy machine-gun and HE shell fire opened up.

ENEMY FIRE DRIVEN OFF

Quick action by

the Dickman's LCS(S) scout beach marker boat in firing a barrage of 34

rockets caused a decided lull in the enemy's fire and drew fire on the boat

itself. This factor was believed to have contributed much to the safe landing

and retraction of all boats in the assault waves. The secondary control boat

PC-624 departed from the rendezvous area on time with the fourth wave, but for

some unknown reason delayed going into the line of departure sufficiently to

make this wave one hour and fifty minutes late in scheduled time. When this wave

retracted, and while proceeding away from the , beach, a medium calibre HE shell

struck the starboard side of the ramp of a Dickman LCM(3) and exploded. Three of

the boat's crew were wounded. The boat returned to the Dickman but could not be

used for the remainder of the operation. A total of seven members of the crew

were wounded.

CONGESTION ON BEACHES SOLVED

Later waves of boats carrying vehicles were not allowed to land immediately on the

beaches by the beachmasters because of machine-gun and artillery fire. As

a result there was much congestion outside the line of departure by boats from

all the transports, The support boats acted as traffic boats and when the

beaches became tenable directed the boats to the proper beaches. Captain

Mauerman reported that a faster and larger boat, about the size of an SC-boat,

would be better adapted for traffic control boats. At about 0100, on the 9th,

Captain P. D. Matterson, British Royal Engineers, Combined Operation Police

Patrol 5, had arrived alongside from the HMS M. Shakespeare to act as beach

pilot with a scout boat. That boat departed and the beach pilot was placed

aboard the Boat Group Commander's boat, where he most ably gave advice and

assistance in the guidance of boats along the shore line and into the beaches.

Three LCVP's and four LCM(3)'s from the Oberon, two LCM(3)'s from the Procyon,

and eight LCM(2)'s from the HMS Derwentdale, arrived alongside on time and were

used to carry priority vehicles into the beach, going in as the 6th, 7th, and

8th waves. All boats from other ships worked smoothly and without interruption.

UNLOADING HINDERED BY ENEMY FIRE IN HILLS PROCEEDS

Unloading of

vehicles and cargo proceeded expeditiously on September 9 and 10, and all

unloading was completed by 1600 on the

second day. Much of the unloading from boats was done by boats' crews. Thirty

men from the Port Battalion were sent to the beach prior to noon on the 10th.

The unloading on the beaches seemed to be held up principally by the continuous

shelling of the beaches from artillery well hidden in the hills behind the beaches.

--119--

U.S. COAST GUARDSMEN HELP SLIGHTLY WOUNDED SOLDIERS COME ABOARD THE COMBAT

TRANSPORT LYING OFF PAESTERNUM, JUST SOUTH OF SALERNO

--120--

Vehicles were

again carried in #7 hold and lowered between decks, and gasoline was placed in

them at the time of the unloading. This caused no delay and proved to be a great

safety factor. The two LCVP'S which had been damaged and trapped in #1 starboard

davit, were out of operation entirely. But seven rudders and five propellers

which had been damaged were replaced. Boat handling by boat crews was excellent

throughout the operation.

SALVAGE WORK

The Dickman's

salvage boat, operating in the vicinity of Green Beach, assisted and

floated many boats and was able to keep the beach clear of stranded boats. One

unidentified sunken boat was marked by an obstruction buoy. The salvage boat

worked under artillery fire from shore most of the time. Five Dickman boats were

stranded on the beach during the entire operation and all were recovered and

immediately placed in operation.

COMMUNICATIONS

Communications in

general were good. No contact between Green Beach and the Dickman was

established on the TBY because of damaged equipment on the beach. The FM 609

between ship and shore worked very well, but was jammed with too much traffic

due to there being so many stations on the one frequency. The TBY worked well on

the shore-to-boat circuits, but the distance was too great and contact could not

be made.

AREA REPEATEDLY BOMBED

Three enemy

bombers made an attack in the area at 0743 on the 9th, and at 2140 enemy

bombers made another attack, but due to the heavy smoke screen made by all

the vessels and boats no bombs fell in the vicinity of the Dickman. At 0445 on

the 10th, enemy planes attacked again and a smoke screen was laid by the Allied

ships. From 2240 to 2312 on that night, as transports were preparing to depart,

a large formation of enemy bombers lighted up the transport area with

vari-colored flares that apparently marked the limits of the area. The

transports ware subjected to heavy bombing. Apparently no vessel was hit. One

bomb fell 600 yards astern of the Dickman. All vessels delivered a heavy barrage

of anti-aircraft gunfire. Fire discipline on the Dickman was good. During this

operation friendly fighter protection of the area was excellent. The Dickman's

support boats patrolling the beach area fired at enemy planes over the beach,

but there were no indications that any hits were made.

CASUALTIES TREATED ABOARD THE DICKMAN

Fifty-seven

casualties were evacuated from the beach and received treatment on board the

Dickman. That number was well within the capacity of the ship.

TWO MAIN FORCES

The Naval

operations were composed of two main forces--the Western Task Force, and Force

"H". The Western Task Force was divided into two--the Northern Attack Force and

the Southern Attack Force. Force "H" consisted of a large covering force of

battle ships, aircraft carriers, cruisers, and destroyers. The Northern Attack

Force was under

--121--

U.S. TROOPS MARCHING UP TO JOIN IN THE ATTACK ON THE GERMANS ON THE SALERNO SHORE.

COAST GUARD MANNED LANDING CRAFT THAT BROUGHT THEM ASHORE ARE VISIBLE IN THE

BACKGROUND

--122--

Commodore G. N.

Oliver, R.N., in HMS Hilary. The Southern Attack Force was under Rear Admiral

John L. Hall, Jr., U.S.N., in the USS Samuel Chase Commander Roger C. Heimer,

USCG. Force "H" was under Vice Admiral Sir Algernon Willis, R.N., in HMS

Nelson. Rear Admiral Sir Philip Vian, R.N., in Force "H" commanded the carriers

which gave most of the fighter cover over ships and beaches at the beginning of

the assault. Rear Admiral Richard L. Conolly, USN, in the USS Biscayne,

volunteered to serve under Commodore Oliver as a Task Group Commander though

actually his senior in rank.

NAPLES THE MAIN OBJECTIVE

The object of the

Western Task Force was to land enough forces in the Gulf of Salerno to

capture a bridgehead for Naples and to secure the neighboring airdromes.

Between Salerno and Agropoli, about twenty miles south, the ground is fairly

flat and the river Sele runs roughly half way between the two. The Northern

Attack Force landed British troops and supplies from the north bank of the River

Sele to a point ten miles further north and about three miles southeast of

Salerno. The Southern Attack Force landed United States troops and supplies

along the beaches from the south bank of the River Sele as far as Agropoli,

eight miles further south. Concurrently with these two main landings, two

smaller landings were made along the coast west of Salerno for the purpose of

seizing important military objectives. A Task Group, partly United States,

partly British, and including the gunboats Soemba and Flores of the Royal

Netherlands Navy, was assigned the duty of occupying the islands off the Gulf of

Naples--Ventotene, Ponza, Prociga, Ischia, and Capri. This Task Group was under

Captain Andrews, USN, in the US Destroyer Knight. A Picket Group of sixteen

United States PT's under Lieutenant Commander Barnes, USN. was assigned the duty

of screening the vessels of the Western Task Force against attack by enemy "E"

boats and other surface craft.

MINESWEEPERS PRECEDE LANDING CRAFT

In both the

Northern and Southern Attack Force areas. the first waves of landing

craft, preceded by minesweepers escorted by destroyers, touched down on

the beaches before 4.00 a.m. on September 9th. Extensive minefields had

been laid in both areas, and we incurred casualties. Many mines exploded in the

sweeps. Frequently under heavy gunfire, the minesweepers did their work with

their habitual skill and gallantry. In the Northern area, the sweepers swept or

exploded twenty mines during the assault and 135 in the first four days.

BEACHHEADS ESTABLISHED FIRST DAY

In spite of enemy

activity in the air and on all the beaches, the work of disembarkation

continued. There were casualties in ships, landing craft and personnel.

The orders that the assault was "to be pressed home with relentless vigor,

regardless of loss or difficulty" was obeyed to the letter. The beaches were

seized and held, in spite of enemy gunfire and counter-attacks. Contact had been

made almost immediately with Germans, but despite strong opposition, the Allied

troops successfully established bridgeheads on the 9th. A diversionary force

captured Ventotene Island, about forty miles west of Naples, during the morning.

The Italian garrison surrendered but, according to press reports,

--123--

U.S. OFFICERS AND TROOPS DISCUSS LAST MINUTE DETAILS OF THEIR JOB IN THE INVASION

ABOARD A COAST GUARD MANNED COMBAT TRANSPORT SAILING FOR THE ITALIAN MAINLAND

--124--

about ninety

German troops put up resistance before they were overcome. By 1530 on the 9th,

the airfield at Monte Corvino, east of Salerno, was in Allied hands,

PORT OF SALERNO CAPTURED

On the 10th,

Fifth Army troops continued to establish themselves ashore, beating off several

German counter-attacks. The port of Salerno about thirty-five miles

southeast of Naples, was captured and steady progress was made inland. According

to press reports, German tanks were in action near Salerno. Other reports said

that the German counter-attacks were broken up with the assistance of naval

vessels offshore, which poured shells into the German ranks at close range.

CHASE ARRIVES

As the Samuel Chase approached her destination, the weather was fine and visibility was

good, with the moon high on her starboard quarter. The sea was running Force 1,

ideal for small-boat operations. At 2315, HMS Shakespeare was passed to

starboard at point KING, and course was changed to take position in the

transport area. The CHASE stopped her engines at 2350 and went to Condition Four

at 0000 September 9, 1943. Huge fires and severe explosions could be seen in the

vicinity of Salerno. An intercepted German message read "Night reconnaissance

aircraft reported Allied shipping off Salerno at 0035B."

COMMANDER HEIMER SENT TO HEADQUARTERS THE FOLLOWING DETAILS

OF THE TRANSPORT'S OPERATIONS AT SALERNO

LANDING CRAFT DEPART

At 0035, LCM #1

departed for the USS Carroll to become part of their fourth assault wave.

At 0130,LCS's 13 and

31, and LCVP's 21 and 26 left the Chase to escort 59 DUKW's to Red, Yellow, and

Blue beaches of the Gasale Greco beach designated for this force. To avoid

losing any DUKW's, boards with luminous letters to indicate the beaches were

mounted on the stern of the escort lead boats and a simple set of signals arranged.

ARRIVE AMIDST ENEMY

At 0345, as heavy

gunfire of small and large caliber was observed on the beaches assigned to

her force, the Chase received word that the first wave of boats had landed

at 0340. At 0400, Wave-3 boats were lowered to proceed to the USS Stanton to

become their fourth wave. At 0500, heavy explosions were observed near the

beaches, presumably from mines. The Sweeper Group which had swept the transport

area had then proceeded to sweep the boat lanes but was forced to discontinue

until daylight because of the many small boats going back and forth. Between

0500 and 0530, an attack in the traditional manner was made on ships to the

north. Much AA fire was observed.

--125--

U.S. SOLDIERS INVADING ITALY LINE THE RAIL OF A COAST GUARD-MANNED COMBAT

TRANSPORT, WAITING THEIR TURN TO CLAMBER DOWN THE SIDE INTO THE LANDING BOATS

THAT WILL TAKE THEM ASHORE

--126--

TROOP DISEMBARKATION COMPLETED

Troop disembarkation was completed by mid-morning. At 0545, 0552, and 0600, the Chase

rail-loaded and lowered boats of Waves 1, 2, and 4 respectively. Major

General Walker, with 96 officers and 1,168 enlisted men, disembarked. Although

light artillery was shelling the beach and boat lanes, and boats had to proceed

with caution due to floating mines, our boats landed at 0752, 0800, and 0805. A

dozen minutes before this, the ship had fired at a lone JU-88 reconnaissance

plane. However, troops were all landed with the exception of port platoon and

communication personnel, by 1005, September 9.

CARGO UNLOADING PROCEEDS UNDER FIRE

Cargo unloading

was begun at 0745, with but very few boats available. Because of the lack

of boats, unloading had to stop for an hour at noon. At this time, the

Chase was fifteen miles from the beach, the vessel having drifted with the

others from its position in the transport area. In the morning, machine-gun

fire, floating mines, and light artillery fire on the beaches and boat lanes

delayed landing of LCT's, LST's, and small boats. As the enemy tanks on shore

opposed the assault, they were taken under fire with shore gun emplacements by

the fire support group. That evening, at 1701, the monitor HMS Abercrombie was

observed to hit a mine and settle somewhat by the stern. Late in the afternoon,

the Chase began moving in through the swept area and dropped anchor inshore, at

1948, in the Gulf of Salerno.

CASUALTIES AND PRISONERS BROUGHT ABOARD

As the boats

returned from the beach, they usually brought back casualties and

prisoners of war. These were brought aboard and placed in charge of the medical department.

NO HELP AVAILABLE ON BEACHES

As the boats

became available and unloading could continue more rapidly, another factor

interfered to slow the operation. There was no one on the beach to help the boat

crews in unloading their boats. Rather, the crews had to manhandle each case or

can, carrying it from where they beached to a point well up on dry shore, It was

not until the morning of September 10 that they again received assistance. This

Condition was a repetition of what had happened at Gela. At 0400, on September

10, unloading operations had to cease due to the congested beaches. All other

ships had stopped before the Chase. At that time vehicles, gas, and oil were

100% unloaded, and ammunition was 90% unloaded.

UNLOADING IS RESUMED

The Chase resumed

unloading at 0700, this time with aid on the beach. The total cargo

unloading time was 25 hours. The ship's cargo was completely unloaded by 1330.

The Chase began to take boats aboard, with the exception of those kept in the

water for despatch and possible smoke-lying purposes.

ENEMY PLANES TRY TO INTERFERE

Throughout landing operations, enemy planes were active, but unable to stop our unloading.

During the morning, about six FW-190's bombed and strafed the beaches. These

were first taken under fire

--127--

THESE FOUR CREW MEMBERS OF A TANK LIGHTER ATTACHED TO A U.S. COAST GUARD-MANNED

TRANSPORT HELPED PUSH THE GERMANS BACK FROM THE BEACHES AT

PAESTUM, NEAR SALERNO. FROM LEFT TO RIGHT, THE INVADERS ARE: COAST GUARDSMAN

LEONARD RUEHLE, 1249 15TH ST., DETROIT, MICH.; COAST GUARDSMAN COOK, KELLOGG

ROAD, DERBY, N.Y.; A. E. LESSARD, U.S. NAVY, 27 BALCOM ST., NASHUA, N.H.; AND

HARRY W. LESSON, U.S. NAVY, EAST STREET, SCHAGHTICOKE, N.Y.

--128--

by the Chase.

Fighter bombers returned again about 1435. Meanwhile, our landing craft

succeeded in carrying enormous amounts of cargo to the beaches.

"WELL DONE" FROM CTF AT COMPLETION

Cargo unloaded

consisted of 88 vehicles, all combat loaded, including thirteen 2 1/2-ton

trucks and four half tracks; 251 tons of mixed ammunition plus two tons of

pyrotechnics; 44 tons of gasoline and oil; and 125 tons of general cargo (water,

rations, and engineers' supplies). Total trips made by Chase LCVP's were 35 for

personnel, 172 for cargo, 15 miscellaneous; by Chase LCM, 17 with vehicles and

personnel gear; by Andromeda LCVP's, 2 personnel and 5 cargo; and two LCT trips,

one with vehicles and one with general cargo. CTF 81's message, replying to

Chase's report of completion of unloading was "Well done."

Chase LEAVES AREA UNDER FIRE

At 2215, on

September 10, the Chase was underway, proceeding through swept channel to

form a convoy leaving the area. Nine minutes later, enemy planes began dropping

flares, and heavy AA fire was observed astern. The Chase went to General

Quarters. Multi-colored flares were dropped all around, illuminating the ships

and landing craft. A concerted bombing attack was then made by both medium

altitude and dive bombers. Six bombs were dropped close aboard the Chase: two

estimated 500# delayed-action bombs, 125-150 yards on the port bow, which

splattered the forecastle with water and jarred the ship; an estimated 250#

delayed-action bomb, which landed about 125 yards, one point on the starboard

quarter; another pattern of two 250# bombs landed an estimated distance of 500

yards away on the starboard bow; and the sixth bomb of about the same size,

landed one point abaft the starboard beam at a distance of several hundred

yards. All air activity had ceased by 2315, so the Chase secured from General

Quarters at 2320. At the time the transport had been traveling at a speed of 10

knots in the northernmost column, with the moon on its south or port side. It is

believed that rather than expose themselves against the moon to AA fire the

enemy planes contented themselves with attacking the northernmost ships.

VESSEL TORPEDOED

As the Chase was

forming a convoy out of the Gulf of Salerno, Italy, with the Andromeda on

the port beam, Stanton astern, and Carroll on the starboard beam, there was an

explosion, on September 11, at 0030, believed to be & depth charge. At 0135,

the screen contacted some "E" boats and fired at them. At 0130 the Rowan was

torpedoed by an "E" boat. The Bristol, which continued to stand by and search

for the attacker picked up 70 survivors. The Chase continued with the convoy,

and on September 14 moored at Mers-el-Kebir, Algeria.

FLOTILLA AT SALERNO

LCI'S UNDER HEAVY FIRE

"Some found the

landing tough," related Lieutenant (jg) Arthur Farrar, USCGR, whose LCI

was part of the

--129--

THROUGH THE GAPING DOORS OF LANDING CRAFT, MOTORIZED

INVASION EQUIPMENT HURRIEDLY ROLLS ASHORE AT PAESTUM

--130--

large invasion

force at Salerno. "We found no opposition," he said, with masterly

understatement, "except for occasional dive-bombing and strafing planes that

kept sneaking in. The one-plane attacks came on an average of one every hour.

Night raids were something else. They were terrific and would occur around 2300

and 0400. The Germans lit up the entire area with so many flares it was possible

to read a paper by the light. Several LCI's got very close calls but none were

destroyed. The 319 received the most serious damage when a plane that was

falling strafed on the way down, causing casualties to some of the gun crew. The

follow-up work was about the same as for the other invasion. We were based in

Sicily for the operation and spent some time ashore. The flotilla was commended

for its work and ordered to England. We were told it was because ours was the

best LCI group in the Mediterranean."

ASSIST VESSELS UNDER ENEMY FIRE

"The real work of

the large LCI's began when the going was the roughest and toughest", said

Lieutenant (jg) Charles Greene, of the Coast Guard, in reviewing operations in

the Salerno area, "for their work was to tow and assist vessels aground, under

enemy fire! Our vessel, Landing Craft, Infantry (large) was assigned as a part

of four of such vessels in our group, including the flagship, to proceed in one

of the very first convoys, with approximately thirty other navy landing craft,

consisting of LCT's and a few British craft. Our duties were to carry troops,

supplies, and fuel for the smaller LCT's and to discharge same upon landing in

Italy, then stand by in the battle area and act as salvage vessels, to assist

those craft which were aground, hit by enemy fire, or stranded on the beach.

REFUEL SMALLER CRAFT

"We departed from

our North African base in the early afternoon, a couple of days before the

actual landings took place, and we proceeded through the swept channels

and mined areas en route to a pre-designated harbor in northern Sicily (then

Allied-occupied) for a short overnight stop to refuel the smaller craft which

could not carry sufficient fuel or supplies. Our escorts consisted of one

British destroyer-corvette, and a few PC's and SC's--small protection when one

considers the final destination, with no rendezvous planned till we reached that

area, right in the enemy's front yard! . . . We arrived at our first overnight stop

right on schedule, and the refueling process was completed in four or five

hours. The LCT's and SC's came alongside our LCI's, while we were at anchor, and

moored for the time required to get fuel lines laid out, and the Diesel oil

pumped over to them . . ."

SPOTTED BY ENEMY PLANE

That night they

lay at anchor, in cruising formation, each ship maintaining a full sea and

gun watch, for they expected trouble from enemy bombers. But nothing

happened that evening. Early the next morning, about 0530, on September 7th, all

the vessels got underway upon orders from their flotilla flagship, and sailed on

the final leg of their mission. They cruised without disturbance from any enemy

action until 1300 o'clock on the 8th, when their small convoy was spotted by an

enemy reconnaissance plane heading for his home grounds. "He took one quick turn

around us, at very high altitude, out of range of our small 20 mm's and

--131--

U.S. COAST GUARDSMEN AND NAVY BEACH BATTALION MEN ARE SHOWN HUGGING THE SHAKING

BEACH AT PAESTERNUM, JUST SOUTH OF SALERNO, AS A NAZI BOMBER UNLOADS ON THEM

--132--

departed for his

airfield with the news of our coming," said Lieutenant Greene. "Our British

destroyer escort had the only large calibre guns capable of reaching the plane,

and he fired a few rounds at the enemy, with no result except to bring home to

all that here we were, discovered, and in enemy waters--thirty miles from his

own bases and only one large vessel for any protection which might be deemed adequate."

FLOTILLA ATTACKED BY PLANE

On the afternoon

of the second day, the flotilla was suddenly attacked and strafed by a

German ME-109F. Describing the battle that ensued, Lieutenant Greene said

that his ship was in Battle Condition No. 2 when General Quarters rang. "All

guns were manned as the plane approached but we were forced to hold our fire

because a sister ship was abeam to port, about 150 yards distant, and the

approaching aircraft made its approach from that bearing, thus presenting us

with the situation of killing our own friends in the nearby vessel. We held our

fire as he dove, watching for a chance to give him a few bursts, but as he came

down, a Flak ship and destroyer fired at him, from long range, The Flak ship

scored a hit, but as the enemy plane came down at terrific speed, all his guns

were blazing at us. The other LCI(L) commenced firing and later claimed several

hits also, but the Messerschmitt's guns never ceased till he crashed between our

two LCI's, showering us with shrapnel and debris. His aim was good,

unfortunately, for we received numerous bullet holes in our vessel, and had five

men hit. One of the wounded was our No. 2 gunner, who was shot above the heart.

The other four men received shrapnel wounds, one in his eyes, causing permanent

blindness, and the others minor wounds in face, legs, and arms."

WORK IS CONTINUED SHORTHANDED

Through that

enemy action, Lieutenant Greene's vessel lost one fourth of its crew and had to

continue work shorthanded. The wounded were taken to a British hospital ship and

cared for, while their shipmates carried on the fight even more intensely. As

the Lieutenant remarked, "When your men are hit--or you ,-- then it is all seen

in a different light'." Not a man complained of overwork, loss of sleep, or bad

food, considering those discomforts as inconsequential. The work had to be done,

and it was done, regardless. Two days later, they were ordered to stand by

Salerno harbor to await a rendezvous for a return to Africa, where they were to

be refueled, reprovisioned, and pick up reinforcements for our troops. When they

left Salerno Bay that afternoon, every man was worn out from lack of rest,

dirty, and practically "out on his feet," but their faces were smiling and it

was thumbs up for victory.

LCI'S ATTACKED EN ROUTE TO SALERNO AREA--FIRE ON ENEMY

"All was quiet

for another hour," Lieutenant Greene continued, "then at 1400, we were

subjected to a dive bombing attack out in the sun, by four Italian fighter

planes. Our first warning of danger came when the destroyer opened fire,

startling everyone; his guns had no sooner barked than a group of bombs fell

into the sea, astern of him; one of these missed our flagship, which was in the

lead, and about seven hundred yards distant, by a very close margin. Estimates

ran as low as ten to fifteen feet, abeam to port. The entire vessel was hidden

by the water geyser thrown up by the explosion,

--133--

THESE TWO BROTHERS MET FOR THE FIRST TIME SINCE THEY

ENLISTED WHEN THEY BOTH PARTICIPATED IN THE INVASION OF SALERNO, ITALY. THEY ARE

COAST GUARDSMAN JOSEPH H. BLUE, LEFT, AND ALOYSIUS BLUE, U.S. NAVY

--134--

and we later

discovered that four of her gyro repeaters and magnetic compasses had been put

out of commission by the near-miss. At this time all crews were at general

quarters, in full war gear. One plane, identified as a Macchi 2001 fighter had

the audacity to dive right over the stern of our convoy and fly up its second

column, at a height of not more than 100 feet! No ships opened fire on him as

they feared hitting their own men, but he came so close to our craft that we

felt our fellow-men to be safe enough from our fire to open up. Guns No. 1, 2,

and 3 tracked him to within 400 yards, then all commenced firing; at this time I

was stationed up forward on our No. 1 gun, and observed the tracers to miss the

plane by a wide margin--trouble; too much lead angle and that is unusual.

The No. 2 gunner was a cool boy; he

waited and saw his chance to fire just at the right time, with the result that

he placed at least a dozen 20 mm shells into the enemy plane, each striking it

just abaft the cockpit on the port side. Evidently the plane was armored, as the

only noticeable effect was his wabbling antics in flight, and a loss of about 50

feet of altitude, this bringing him down to about our height above the water. He

gunned his engine and zoomed away--headed for home."

ONE LCT IN FLAMES

The flotilla did

not escape unscathed, however, for one of the LCT's, the 624, was hit

squarely by a bomb and burst into flames. The survivors were picked up and the

craft sank in a few minutes. The oil slick on the surface burned for hours.

"Miraculously, we were not attacked again that afternoon or evening," Lieutenant

Greene reported, "for by that evening our large convoys with bigger ships had

arrived, and were a few miles astern of us. The enemy bombers went after them

and let us go." That evening, just after dusk, the convoys astern were subjected

to an air attack, but they defended themselves well and men in the flotilla

observed three flaming airplanes streak out of the sky in as many minutes and

crash into the sea, burning and illuminating the horizon where they fell.

RAGING INFERNO ON D-DAY

"It was D-day

(9th September) and H-hour (0330) a few minutes away; we could see Mt.

Vesuvius sputtering and flaring up on our port side, every minute or so," the

Lieutenant went on, giving a vivid description of the battle scene. "Though the

night was dark, there were all kinds of lights to be seen--flares, gun flashes,

and the colored signal lights: red lights, green lights, white lights, flashing

and steady. We stared at our watches, awaiting H-hour.--Suddenly we knew it had

arrived. Countless gun flashes and explosions rent the air, both from ship to

shore and vice versa. Tracer streams criss-crossed everywhere, and in several

places we could see lines of fire running parallel to each other, but from

opposite directions. The heavy batteries on the cruisers and destroyers opened

up and displayed a beautiful yet awe-inspiring sight. You could see, following

the yellow gun flashes, the path of the large projectiles as they took flight,

not rapidly in a breath-taking ruse, but slowly. The shells appeared as red-hot

rivets, easily recognized that rose slowly in a curving path till they levelled

off, moved on a few more seconds, then dipped, fell slowly to earth, and

exploded in a glaring flash. There was so much to see that

--135--

COMPARING CLOSE CALLS WITH DEATH WAS A FAVORITE

CONVERSATIONAL SUBJECT AMONG SOLDIERS AND COAST GUARDSMEN

ABOARD A COAST GUARD-MANNED TRANSPORT RETURNING FROM SALERNO

--136--

it was difficult

to watch and grasp the immensity of the whole operation. It was tremendous. And

it appeared more so when we realized that here, before our eyes, an alien force

was present, and with its power and military might was seeking to destroy the

defenders of a whole nation so that it might conquer that nation!"

LANDINGS HEAVILY REPELLED

The invasion

craft were due to go off that beach--a raging inferno of exploding shells

and smoke--at H-hour plus 30 minutes, and stand by there for further

orders. And when the time came, they were there. Landings by LCT's with their

tanks, and LCI's with their troops were to take place at H-hour plus 50-60

minutes, but this was not possible with any degree of success, because enemy

resistance was unusually strong. However, small craft were able to sneak in

under the barrage of fire and discharge enough infantrymen to keep the enemy

busy ashore, temporarily. Meanwhile, the large cruisers and destroyers were

fighting it out with shore batteries and German tanks. Tanks had been brought to

the beaches at Salerno by the Germans to repel the invasion. Our large ships had

to fight off the tanks for we had none of our armored vehicles ashore to speak of.

ENEMY FORCED TO RETREAT

Fighting had not

diminished noticeably by 1030 the next morning, D-day, but our planes came

over and spotted and bombed every enemy shore installation. Our larger ships

then fought a duel with the enemy forcing them to retreat and permit the landing

of tanks, trucks, men, and supplies. British destroyers and cruisers moved near

shore and shelled German tanks, which were entrenched in the hills and firing

down into Salerno Bay at the Allied vessels. Destroyers laid smoke screens to

shield the landing barges and small craft from enemy view. One small boat was

struck by an 88 mm tank shell on his starboard quarter and began to belch smoke

before he raced away out of gun range at full speed. But the landings proceeded

according to plans.

ALLIED SUPERIORITY IN THE AIR MAINTAINED

During daylight,

German planes made only quick, hit-run attacks. They made lightning fast

strafing or bombing raids and then zoomed away into the hills,

flying close to the ground. The Allies had air superiority, and were using P-38

fighters and Spitfires for air coverage. Although a few dogfights did take

place, the Germans seemed to have great respect for the P-38, not staying long

once they were seen and chased by the Allied airmen.

ENEMY ATTACKS AT NIGHT

The worst hours

were during the night. The enemy bombers struck just after dusk, their

raids lasting from a few minutes to an hour and a half. Men rushed to

battle stations as General Quarters was sounded as many as four times during one

sea watch--four hours. "These attacks presented the worst aspect of the whole

operation, for we, on the small craft, could not see the planes or shoot at

--137--

COAST GUARDSMAN STEPHEN G. FERKO, SEAMAN FIRST CLASS, OF

ASHLEY, PA., ASHORE AT AN ITALIAN PORT POSES WITH A NEW CHUM

--138--

them, our guns being of too small a caliber, but we could hear the

roar of engines as they dove, dropped flares, then came back to lay their eggs,"

Lieutenant Greene reported. "Very discernible above the noise of anti-aircraft

gunfire were the high-pitched whine and whistle of bombs which fell and struck

nearby. Close ones always detonated with a terrific roar, and small craft like

ours would vibrate from the concussion."

MEN AWAKE PRACTICALLY ALL DAY AND NIGHT

"The raids forced

the officers and men to stay awake practically all night long," the

Lieutenant continued, "and when you remember that our work of

unloading transports of their troops and supplies took all the daylight

hours, then you may well realize how much sleep was gotten. No one, I am sure

got more than one hour's unbroken rest at only one time. Men would be relieved

from gun stations, but would fall to the deck where they were and try to catch a

few minutes' sleep. Chow was carried to the men at their gun stations by mess

cooks. After three days and nights of this, human nerves became taut. Men would

jump, startled at noises caused by the slamming of a hatch or the clatter of a

falling helmet."

OFFICIAL REPORT OF FLOTILLA BY CAPTAIN IMLAY

Captain Miles H.

Imlay, USCG, Commander of LCI(L) FLOTILLA FOUR, of the U.S. Amphibious Force,

sent an official report, dated September 14, 1943, to the Commander in Chief,

United States Fleet.1

The report rich with detail, includes suggestions of great

value in future amphibious combat operations, as regards the handling of LCT convoys.

IMLAY AGAIN DECORATED

As in the

Sicilian landings, so in the landings on the Italian mainland, Captain

Imlay played a leading role, and was decorated. His citation follows: "For

exceptionally meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding services to

the Government of the United States as Commander of the LST Convoy of a Major

Task Force during the amphibious assault upon Italy in September 1943. Charged

with the difficult assignment of bringing the vessels under his command safely

through the hazardous course between Bizerte, Tunisia and the Gulf of Salerno,

Italy. Captain (then Commander) Imlay performed his essential duties with

outstanding skill, successfully reaching the designated assault beaches at the

assigned time despite extremely adverse weather conditions and fierce enemy

aerial opposition. By his keen judgment, brilliant leadership and tenacious

devotion to duty, units containing vehicles and equipment necessary for the

accomplishment of the attack were unloaded in accordance with previous landing

plans, thereby contributing materially to the success of our forces in this

vital war area."

--139--

THIS U.S. COAST GUARDSMAN HAS A USEFUL SOUVENIR OF THE FIGHTING IN THE NAPLES AREA --

AN ITALIAN MAIL BAG

--140--

THE COMMUNICATIONS ASPECT

Lieutenant (later

Lt. Comdr.) Ed C. Phillips, USCGR, Communications Officer aboard the USS Bibb

from April 23, 1943, to June 2, 1944, sent in the following account of Coast

Guard operations in the Italian campaign, from the Communications angle:

It may be of

general interest in considering Coast Guard participation in the late war for a

general report from the communications aspect in connection with convoy

operations between this country and the Mediterranean.

Most of the UGS-GUS (U.S.-Gibraltar-Mediterranean) convoy task forces were headed by Coast Guard

cutters as flag ships, carrying a U.S. Navy officer aboard as the task force

commander. The task forces themselves were made up of both Navy and Coast Guard

destroyers and destroyer escorts. Convoy operations in the Atlantic were

conducted under a command arrangement with the British Admiralty which divided

operational control between American and British authorities at a CHOP line

located at approximately 30 degrees west longitude. Communication requirements,

therefore, necessitated considerable experience in both American and British operations.

During the early

days of the war there were marked differences in the communication methods of

these two allied services. Such differences were considerably lessened in later

operations due to combined communication agreements and the combined use of

certain of our coding devices. Most of the early convoys destined for the

Mediterranean and beyond were turned over to British task forces at Gibraltar

for escort beyond that point. Communications during the early operations were in

many cases carried out under considerable confusion. New code books were called

for and familiarity with British operations was essential.

In later

operations the U.S. task forces continued their convoy escort duties into the

Mediterranean as far as Bizerte. Because the Mediterranean area was an active

war theater, and because theater operations called for communication activities

of a different type than those experienced in the purely Atlantic operations,

the theater command evolved a plan for the use of liaison communication officers

within the Mediterranean area in an effort to smooth over the difficulties

resulting from the differences in operating methods, etc. This plan in practice

was very successful and, in this writer's opinion, was a most desirable and

farsighted move on the part of the authorities responsible.

In actual

practice the plan worked as follows: As a convoy approached Gibraltar one of the

escorts was sent ahead to enter the port and there pick up an American liaison

officer who had previously been trained in British communications operations.

This officer was supplied with all the latest communication

--141--

A COAST GUARDSMAN GUARDS TWO SLIGHTLY WOUNDED NAZI PRISONERS ABOARD A U.S. COAST

GUARD-MANNED COMBAT TRANSPORT OFF SALERNO, ITALY

--142--

operational information, code books, routing information, and other matters of vital

interest to the task force commander. Upon boarding the task force flag ship, he

served on the staff of the task force commander throughout the period that the

task force was in the Mediterranean waters and was placed ashore at Gibraltar as

the task force departed from the area.

During the days

of the war covering this period, this writer made seven or eight round trips as

the Communications Officer aboard one of the C.G. flag ships of the type

mentioned and had an adequate opportunity to observe the remarkable progress and

improvements made in naval communications, both within the U.S. Naval service

and as they were applied jointly to combined operations. In retrospect, it seems

hardly possible that what was done could have been done in the time available.

The Communications organization of the Navy became geared in a very short time

to a pitch of activity which allowed a task force of naval vessels to shepherd

large convoys, in some cases amounting to 100 vessels at a time across the

Atlantic and into the actual war theater with a minimum of uncertainty and lack

of information.

Reports of other

convoys, their positions, courses and speeds, the reports of enemy submarine

movements, the reports of movements of our own and allied naval units, and the

reports of neutral shipping were regularly received over the U.S. and British

fox schedules. Such information, of course, enabled the escort vessels to

maintain a continuous plot of the movements of all surface and underwater

vessels, both friendly and enemy, at all times. One must have been on actual

convoy operations to appreciate the utter confusion which can be caused by the

unexpected appearance in the path of a large convoy of even a friendly vessel,

to say nothing of the havoc that can be caused by an enemy unit.

It is doubtful

whether any other service played a greater part in the remarkable record of

convoy operations than that of the naval communications service. Aside from the

fact that a large portion of the actual convoy operations were conducted by

Coast Guard vessels and Coast Guard personnel, who became most proficient in

naval communications matters, no special credit in this phase of the operations

can be claimed by Coast Guard Communications, as such.

ACCOUNT OF CHARLES P. GIAMMONA, COX, USCGR

It was a dark,

misty morning when we started in for Salerno. We heard the night before that

Italy had given up, but we were taking no chances. Our control boats gave us the

O.K. signal and the first wave started in before sun-up. As soon as the first

boats hit the beach the Germans started to open up from the hills. I was in the

fourth group going in, and it was like walking into a sheet of fire. We had

swell air support, but the shells were splashing all about us.

--143--

AN AMERICAN CARGO SHIP HIT BY NAZI DIVE BOMBERS DURING THE INVASION OF SICILY. FIRE

STARTED BY BOMBS DROPPED AMIDSHIPS SPREAD RAPIDLY TO THE SHIP'S MUNITIONS SUPPLY

--144--

We call them

"whistling death." You can hear them whistle, then splash. I had learned from

Sicily that it is the ones you don't hear that you have to watch out for.

The beach was

wide and flat and as we hit the sand and unloaded the troops they seemed to

concentrate on us. Those boys had plenty of guts. They couldn't see the enemy

but they went right in and they were plenty sore, too.

After our troops

were unloaded we pulled up the ramp and started back. We were congratulating

each other on getting the guys in safely. All you think about is getting the

boys in. Once the men are on the beach you know your job is done - for a while.

We hoisted the ramp and started back to get another load when all of a sudden

something happened. I didn't hear anything, but I felt as if I was hit by a

sledge hammer and was numb all over. We were hit on the starboard side by a

shell. I figured the boat was done for and I tried to get up. My lifebelt was

blown off completely and my trouser legs were in shreds. My medal and dog chain

were blown off my neck. Fortunately, my water canteen and jacket absorbed plenty

of the shrapnel and they probably saved me. My buddies picked me up and laid me

across the engine hatch and the coxswain gave me some morphine, but I still hurt

all over.

We ran into a PC

boat on the way back to the ship and they put me on board. A pharmacist's mate

fixed me up with some sulfa drugs and while I was lying on the deck the PC kept

firing, and I jumped every time a shell was ejected.

Finally I was

transferred to a transport and a doc dug out some of the shrapnel. Later they

gave me two pints of blood plasma, and I think I owe somebody a pint because I

gave a pint to the blood bank when I was a civilian in Chicago, and the first

chance I'll pay it back, too.

FIRST HAND ACCOUNT OF SALERNO INVASION

William F. Forsythe, Coast Guard Combat Cameraman sent in the following description of the

invasion of Italy at Salerno:

These amphibious

landings are getting monotonous in a ghastly sort of way. They're getting

tougher as we go along, and don't let anybody kid you that the United States

isn't paying a price for such places as Sicily and Salerno, Of course the radio

reports and newspaper headlines sound very encouraging to the folks back home

but there's a lot of American boys getting killed, but I suppose that's the

price of war.

I was stationed

aboard a Coast Guard-manned assault transport for the attack on the Italian

mainland. Just before we arrived at

--145--

U.S. SOLDIERS WITH A SURRENDERED ITALIAN FLAG AT A VILLA A FEW MILES FROM THE

BEACH AT PAESTUM, ITALY

--146--

the rendezvous

one section of our convoy was attacked heavily by enemy bombers. The ack-ack

looked like about a thousand Roman candles together. They finally went away and

we proceeded to our rendezvous area.

There was some

heavy firing north of us about 10 miles but, none in our immediate vicinity.

"When the first few assault waves went in it was comparatively quiet, but when

they landed and the ramps went down the bottom dropped out. The Germans had

concealed machine gun nests that did a lot of damage to our first few waves.

After daylight the Germans were pushed back from the beach about a mile and

started laying it in with mortars and 88's. I was leaving the ship about 2 hours

after daylight when two high altitude bombers dropped their load near us. After

they left I proceeded in to the beach. The shelling was so heavy there that we

had to wait out about a mile until it lifted.

Coast Guardsmen

ran LCVP's in to the shore and the soldiers unloaded them. (An LCVP is a landing

craft for vehicles and personnel). The Army engineers removed the mines on the

beach. These engineers, incidentally, are all veterans of the Sicily and Africa

campaigns. The Coast Guardsmen meanwhile took temporary charge of German

prisoners.

All this time the

Germans had fallen back to their prepared positions about three miles from the

beach and were continually laying in on the beach and in the water their mortar

shells and 88's. We had excellent aircraft protection but once in a while a

Messerschmitt would sneak through and strafe the beach. Incidentally, those 88's

sure make a noise and for some reason they certainly do spread the shrapnel.

Upon returning to the ship I made shots of unloading and wounded coming aboard.

There was very little enemy activity during daylight near our ship but that

night I think everybody in the German air force, even Goering himself, must have

been flying over us. We had the misfortune of a full moon until about midnight.

I hate to say that the Germans are lousy bombers cause my remarks might bounce

back on me but anyhow they didn't hit anything that night--but they sure scared

most people.

The next morning

things were fairly quiet and unloading went on in great haste. Then nightfall

again, and the same old routine. Those Germans were certainly anxious for us to

taste those bombs. We expended on this ship alone thousands of rounds of

ammunition in a few hours. Then about midnight we shoved off. There must have

been somebody tickling the stern of this ship because she really did get up the speed.

I have covered a

great many stories in my 15 years as a news-photographer but I have never yet

seen anything to equal the grit and courage of the soldier from Texas who had to

have his leg amputated as a result of machine gun bullets. A young Coast

Guardsman gave blood to help this boy through his operation. It's little

incidents like this that make this world not a bad place to live in after all.

The last thing the soldier said as I left him was "How about getting

--147--

INVADING AMERICAN COAST GUARDSMEN AND SOLDIERS MAKE FRIENDS

WITH AN ITALIAN FAMILY NEAR THE BEACH AT PAESTUM

--148--

some pictures of my of my operation?"

The boat crews

that manned the invasion boats certainly deserve the credit for continually

running back and forth into the beach in the face of heavy enemy fire.

Coast Guardsman

Bernard J. Miller, BM2/C, attached to the Dickman, acted as wave commander for a

unit of British boats. When the first 88 hit his boat, he attempted to run It

out of the line of fire but evidently the British engineer of the boat must have

been wounded, and when the second one hit they had to bail out. Both 88's hit

the boat amidship and killed approximately 20 soldiers. After remaining in the

water for about an hour, he was picked up by a British support boat and taken

aboard a British transport.

Ensign Walter R.

Samuelson, USCG, also of the Dickman, silenced two machine gun nests long enough

for the troops to leave the boat safely. Meanwhile, Coast Guard Coxswain, Jack

N. Miller, of the Dickman, stayed at the wheel of the landing craft in spite of

enemy machine gun fire, which knocked off part of the steering wheel and threw

splinters in his hands and face. He brought the boat in to the shore.

Coast Guardsman

Philip E. Barnard, CBM, of the Dickman, headed the crew of a landing craft which

was hit by one of the German 88's. After the ramp of their boat was hit while

they were returning from the beach following the unloading, two of the crew

members were seriously wounded and taken off by a support boat. Barnard and one

other Coast Guardsman brought the boat back to their transport alone after a

hard struggle.

ITALIANS COOPERATIVE

A gratifying

feature of the Mediterranean campaign was the attitude of the Italian people.

After momentary and quite understandable confusion, the Italian civilians

welcomed our troops. They regarded the Americans not as invaders but as

liberators who were freeing Italy from the twin tyrannies of Fascist misrule and

Nazi domination. Most of the Italian troops were in German-occupied areas and

for the most part were unable to offer effective resistance to the Germans, who

were disarming them. However, some Italian units fought bravely against the

Germans, and Italian civilians rendered very effective aid in sabotaging German

installations and communications, and in guerrilla operations. The Italian Fleet

was placed at the disposal of the Allies. Marshal Badoglio urged the Italian

people to give us the fullest cooperation in attacking the enemy.

ARMISTICE SIGNED WITH ITALY

Political events

of that period far outran the military program. On September 3, 1943,

Italian commissioners signed an armistice with representatives of the

Allied headquarters in Sicily. This agreement provided for the surrender of the

Italian Navy, for placing all Italian resources and facilities at the disposal

of the Allies, and anticipated Italy's ultimate participation in the war on the

Allied side. Because large German forces were known to be in Italy,

--149--

TWO CAPTURED MEMBERS OF A GERMAN PANZER DIVISION THAT MADE IT HOT FOR THE AMERICANS

AT SALERNO TELL AN AMERICAN ARMY OFFICER AND A COAST GUARDSMAN WHAT THE BATTLE

LOOKED LIKE FROM THE GERMAN SIDE

--150--

the announcement

of the armistice was withheld until September 8th. As early as August 18, 1943,

Allied leaders at the Quebec conference were said to have asked General

Eisenhower to advance the date of an invasion of Italy in view of the collapse

of the Fascist regime and the pending armistice negotiations.

ONLY GERMAN OPPOSITION MET

On September 3,

the same date on which the armistice was signed, the British Eighth Army

under General Montgomery, landed on the eastern coast of the Straits of Messina

between Villa San Giovanni and Reggio Calabria. This landing was opposed only by

the German 1st Parachute Division, and General Montgomery's forces made rapid

progress. The important Italian naval base at Taranto was occupied by a British

landing force on September 9th. On the same day units of the United States Fifth

Army, under command of Lieutenant General Mark Clark, together with British

forces, landed on the Gulf of Salerno in a bold attempt to cut off German forces

in southern Italy. General Eisenhower, realizing the hazardous nature of this

attempt, used a familiar baseball expression to describe it: "It is now time to

step up to the plate and try for a home run."

BITTER FIGHTING

John Folk, Chief

Photographer's Mate of the Coast Guard, in giving the following account,

said that the invasion of Gela, in Sicily, was a "pink tea" compared with the

invasion of the Italian mainland. Far from being able to cut off the Germans in

the south, General Clark's army was forced to fight for its life from the very

outset. For seven days, from September 9 to September 15, bitter fighting raged

on the Salerno beachhead. "I went in with the first wave from our ship, the

Dickman," said Folk. "Our task force landed near the town of Pasternum, south of

Salerno. We were flanked on the left by British forces and on the right by

Germans. The enemy was prepared for us. The beach where we landed contained

hundreds of mines. Heavy artillery up in the hills dropped a constant rain of

shells on us."

FOXHOLES NO PROTECTION

"Immediately upon

hitting the beach, I made for some sparse cover about seventy-five yards

from the water's edge and proceeded to dig in," Folk continued. "Unfortunately,

I had picked out the hottest spot for my foxhole. For about an hour I was forced

to stay there. Shells were screaming over my head and landing on the beach. They

actually clipped the grass above me. Two of them hit extremely close to me. One

hit the ground just a few yards away, and the concussion kicked me in the chest

like a mule . . . Those foxholes were a very good place to be when the enemy had

the range. I picked a piece of hot shrapnel out of my life jacket which was

lying on the ground. A souvenir!

DIVINE HELP SEEN

"As soon as our

forces got the guns that were giving us such a hot reception, I ventured

out to begin making a few pictures," said the photographer. "Enemy guns up in

the hills were very well hidden and difficult to erase; much more so than in

Sicily. My stuff this time probably won't be so spectacular as at Gela. There

--151--

--152--

won't be any

bombing shots, as we had marvelous air cover for this job. In one day, before

noon, our fighter planes knocked down twenty enemy aircraft of their way to

attack us, and repelled forty attempted raids . . . God rode the bridge with us

again on this trip, and after my cruise to date. I am certainly humble in His

presence. Please inform Headquarters that there are no Atheists on board this ship."

EXPERIENCES ON A PATROL CRAFT

Two U.S. Coast

Guardsmen, whose dauntless little Patrol Craft led the invasion into Licata,

Sicily and the Gulf of Salerno, Italy, then stood by as a reference ship doing

highly important work for the protection and direction of the invasion fleets

while the shooting war broke loose all about it, later gave vivid descriptions

of their experiences.

John Raymond

Herdt, USCG, Soundman 3/C, and Arthur Robert Davison, USCG, Fireman 1/C, were

among the casualties of the Italian campaign, who later fully recovered due to

excellent medical attention both in the war zone and later at the Naval Hospital

in the Charleston Navy Yard. They were wounded in the legs by shrapnel from

shells shot at them by a German plane. Davison was manning a 20-mm machine gun

while Herdt was about five feet behind him passing the ammunition as fast as the

gun could take it when the shell struck the deck and exploded between them. Six

of their gun crew were splattered with shrapnel from the same shell. Four others

later returned to duty.

Their little

craft was patrolling the beach at Salerno early on the morning of the invasion,

September 9, when the enemy plane dropped a flare over the ship and then

strafed its decks unmercifully. This scrappy little Coast Guard craft was in

the vanguard of the invasion fleets on reconnoitering duty in both the landings

on Sicily and Italy. Then it stood by to direct the invasion barges into the

harbor, its guns bristling in anticipation of the enemy aerial attacks, which came.

It went through

similar operations at Licata in Sicily where, as a reference vessel, it

approached the Sicilian shore about two or three hours ahead of the fleet, and

anchored 1,500 yards off shore to direct the invasion barges into the harbor.

Three searchlights played on the ship from behind the enemy shore batteries for

hours, but nothing happened. "Talk about suspense," said fireman Davison, "I

always heard about that in books and movies, now I know what suspense really

means. Did you ever figure what it would be like sitting in the electric chair

waiting for them to turn on the juice? Well, that's what it was like, I'm glad

they didn't turn it on, though."

--153--

A COAST GUARD-MANNED PATROL CRAFT

--154--

Soundman Herdt's

description of the approach to Salerno follows: "We drifted in toward the shore

and cut off our motors. We'd start up one of our motors every once in a while

trying to keep our position in the swells. We had left the convoy about 6

o'clock on the evening of the 8th and had gone ahead of it at increased speed.

When we got close to Salerno, several miles off shore, it was about midnight.

The Germans started bombing our convoy about that time. We heard the German

planes come over and saw them bombing the convoy off in the distance. Our ships

were about three miles behind us at the time.

"Our ships were

firing their anti-aircraft guns. We could see their tracers. The sky was just

red with them. We heard a big explosion and a big flash. That was when they got

one of our Navy tugs, A German bomber came over us and our forward gunner,

firing thirteen rounds of the 20MM gun, caught it in the right motor and brought

it down. It flared into flames, hit the water and disappeared. This occurred

just off the Isle of Capri.

"At the zero

hour, early on the morning of the ninth, we were in our position and could see

the convoy coming up slowly. Our skipper hollered to the LSTs and the LCIs,

giving them their position and they went into the beach. The enemy gun positions

on the shore began firing at us at this time.

"When our troops

began making their landings, there were big explosions, fires and we could see

some of our smaller barges get blown to bits. Our cruisers and British cruisers

and destroyers opened up on the beach and shelled the h-- out of them. Then there

really were some big explosions. It looked like the whole beach was on fire.

"That's about all I remember of the actual landing before I got hit.

"You know," Herdt

continued, "we didn't really worry about anything while we were going into the

beach. You don't have time. Everybody is excited, of course. But we all stuck

together pretty close on our ship.

"Davison was

manning a gun and I was standing right by the hatch of the after magazine,

passing ammunition, and we were caught in the flares when the planes came over.

There was a lot of gun firing and something hit the deck. It was a shell that

splattered us all. It was early in the morning and dark shortly before the

planes came. But when they dropped flares, the whole scene was lit up like a

Christmas tree.

--155--

COAST GUARD MANNED PATROL CRAFT

--156--

"From what I've

seen of invasions, they aren't very pleasant. Shells and bombs and flares are

exploding everywhere, lighting up the sky all around you. I wasn't really

scared. It was kind of exciting and I was just excited until afterward.

"Yes, you just

sweat it out," chimed in Davison. "And I don't mind admitting that I was awfully

nervous, especially when I knew the ship's anchor was down as it was at one time

in the Sicily invasion."

"That was the

time we anchored right off the shore of Licata," Herdt said. "We weren't

attacked and never could figure that out. We were a good two hours ahead of the

convoy and all the time we anchored there, there were three searchlights from

the beach practically on us all the time. Everybody was worried about the

searchlights. We didn't worry about anything else. We thought we were going to

get it all the time and the popular remark after the lights were shot out was:

'I've aged about ten years tonight even if we get out of this.'"

Both Herdt and

Davison were awarded the Purple Heart Medal in the Naval Hospital at Oran by

Commodore C. M. Yates, Commanding Officer, U.S. Navy Operating Base, Oran, Algeria.

RESULTS ACHIEVED

AMERICAN-BRITISH JOINT PLANNING SUCCESSFUL

The landings at

Salerno called for the same joint and meticulous planning as the assault

upon Sicily. Above all, with Americans commanding British, and

British commanding Americans, the operations provided one of the finest

examples of the complete cooperation and unity of purpose of the British and

United States Navies fighting side by side in action. It was the first occasion

in which the American and British Navies were in action together against the

enemy in full force and in a new type of warfare. The perfect cooperation and

harmony of the Allied Navies in that very severe test augured well for the

Allied cause in the Pacific as well as in the other theatres of war. Without the

support of the Allied Navies, experts agreed, Salerno would never have fallen

into our hands, and it was more than likely that the Fifth and Eighth Armies

would have remained in the heel of Italy. As it was, the Army landed

successfully on the mainland of Italy in the face of determined opposition by

superior forces of the enemy.

CRISIS SUCCESSFULLY PASSED

After the failure

of the Fifth Army to break out of the Salerno beachhead, everything depended on

the rate of advance of the British Eighth Army, which now assumed the role

of a relief force. On September 10, General Montgomery's array reached Pizzo, 45

miles north of Reggio Calabria. Two days later, part of his

--157--

LT. GRADY R. GALLOWAY

--158--

army occupied the

important port of Brindisi; and on September 17, advance elements of the British

Eighth Army made contact with patrols of the American Fifth Army outside

Salerno. The first great crisis of the Italian campaign was successfully passed.

NAPLES AND FOGGIA CAPTURED

After the first

failure to entrap German forces in the south, the immediate Allied objectives

were the great Italian air base at Foggia, and the port of Naples. With Naples

and Foggia in Allied hands, General Eisenhower's troops would have both a

first-class port of supply and a first class air base at their disposal. Foggia

was occupied by the British Eighth Army on September 28, and on October 1,

advance patrols of the Fifth Army entered the outskirts of Naples. Before

retreating from Naples and Foggia, the Germans had systematically destroyed

these bases, and an immense amount of work was required to put them into shape

for use.

GERMAN DIVISIONS PINNED DOWN

Bitter fighting

in the next months, although disappointing from the territorial or political

view, were not without important bearing on the over-all picture of the

war. Approximately twenty German divisions were pinned down in Italy that could

not be used against the Red Army or against the main Allied invasion of Europe.

Considerable enemy resources were being expended in a non-decisive theatre. A

steady attrition cut down the effectiveness of German units, though they fought

in Italy with all their veteran skill and accustomed tenacity.

MANY OFFICERS AND MEN WERE DECORATED

Lieutenant (jg)

Grady R. Galloway was awarded the Silver Star for action in the initial assault

at Salerno, Italy, where he played a conspicuous part in the invasions of Africa

and Italy. His citation, issued in the name of the President, reads: "For

conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action while serving as Amphibious

Scout and Beach Marking Officer during the amphibious assault at Salerno, Italy,

on September 9, 1943. Displaying great daring and outstanding skill, Lieutenant

(then Lieutenant, Junior Grade) Galloway placed his craft in the center of the

landing beach within two-hundred yards of enemy machine-gun emplacements. When

intense hostile fire swept the area as the first wave of boats attempted to

land, he coolly directed the "firing of a rocket barrage, overcoming immediate

enemy resistance and enabling our forces to beach successfully. Lieutenant

Galloway's inspiring leadership and tenacious devotion to duty in the face of

grave peril were in keeping with the highest tradition of the United States

Naval Service."

James Edward

Hasburgh, was promoted to Chief Boatswain's Mate for shepherding 24 landing

boats from his Coast Guard manned transport into the shell-torn beach at

Salerno, without losing a single craft. It was a small-boat journey of more than

twenty miles. Two days after the Salerno landings, Hasburgh escaped with his

life by a quick dive into a

--159--

CAPTAIN RAYMOND J. KAUEBKAN, U.S. COAST GUARD, PRESENTS

THE PURPLE HEART TO FIVE MEN WOUNDED DURING THE SALERNO ACTION. FROM LEFT TO

RIGHT THE COAST GUARDSMEN ARE: JAMES M. HAMBLIN, POTOMAC MILLS, VIRGINIA;

CLARENCE W. HOLLON, 2216 ARLINGTON AVE., MIDDLETON, OHIO; STEPHEN A.

SPRINGSTEEN, GARDEN AVENUE, GREENLAWN, LONG ISLAND, NEW YORK; JACK N. MILLER,

ROUTE 2, EUSTACE, TEXAS; AND CHESTER WITOWSKI, 8344 MAXWELL, DETROIT, MICHIGAN

--160--

foxhole. His

landing boat had broached to on the beach after a heavy swell, and he had

received permission to have a bulldozer give his stalled craft a shove into the

surf. Just then a Nazi bomber suddenly swept down. Hasburgh jumped in one

direction and landed in a foxhole. Two Army officers in charge of the bulldozer

jumped for another spot. They were found dead without a mark on their bodies.

This was attributed to concussion caused by the bombs when they exploded.

Other citations were as follows:

Lieutenant Commander Bernard Edward Scalan, United States Coast Guard: "For conspicuous

gallantry and intrepidity in action while serving as a Boat Group Commander

during the amphibious assault at Salerno, Italy, on September 9, 1943. Braving

intense fire from enemy shore emplacements, Lieutenant Commander Scalan

skillfully marshalled and led the first and succeeding boat waves to the

assigned assault beach, maintaining effective control of landings in spite of

fierce enemy opposition. Lieutenant Commander Scalan's brilliant leadership and

tenacious devotion to duty contributed immeasurably to the success of our

assault operations in a vital area and were in keeping with the highest

traditions of the United States Naval Service."

Philip E.

Barnard, Chief Boatswain's Mate, United States Coast Guard: "For exceptionally

meritorious conduct in the performance of outstanding service to the Government

of the United States while attached to the U.S. S. Joseph T. Dickman during the

amphibious assault at Salerno, Italy, on September 9, 1943. In the face of

intense, accurate enemy gunfire, Barnard skillfully maneuvered his heavy landing

craft to a successful landing on the correct beach and expeditiously unloaded

the assault troops and vehicles. Although his boat was badly damaged and three