Chapter Three

WEATHER AND THE CONTROL OF AIRCRAFT

A. IMPORTANCE OF WEATHER.

B. SOURCES OF WEATHER INFORMATION.

C. WEATHER INFORMATION FROM RADAR.

D. WEATHER AND STATIONING THE COMBAT AIR PATROL.

E. WEATHER AND INTERCEPTION.

F. STACKING OF COMBAT AIR PATROLS.

G. INTERCEPTING A SINGLE BOGEY.

H. WEATHER AND THE CONTROLLED INTERCEPTION.

I. WIND AND LANDING.

--15--

Figure 24.

Chapter 3

WEATHER AND CONTROL OF AIRCRAFT

A. IMPORTANCE OF WEATHER

In conducting air operations weather directly affects the amount and type of flying as well as the effectiveness of aerial missions. In offensive operations, weather influences the type of attack, numbers and deployment, and time and direction of approach to the target area. Since the enemy may also take advantage of meteorological conditions in timing their attacks against us, weather also influences the number and positioning of our defensive aircraft.

B. SOURCES OF WEATHER INFORMATION

There are various sources of weather information available to CIG to aid in control of aircraft.

1. General area forecasts issued by the command center on the basis of reports from far-flung weather stations from the Arctic to the tropics.

2. Local aerological department reports.

3. Ship's own radars.

Figure 25.

--17--

4. Special weather reconnaissance flights.

5. Spot reports by combat air patrols and other routine flights.

A combination of available weather information aids the CIC officer in stationing the CAP, making successful interceptions, homing aircraft, giving navigational data to pilots, and passing on reliable information to the bridge and to the OTC. A knowledge of weather conditions outside his immediate area is vitally important to the OTC in planning action for the immediate future.

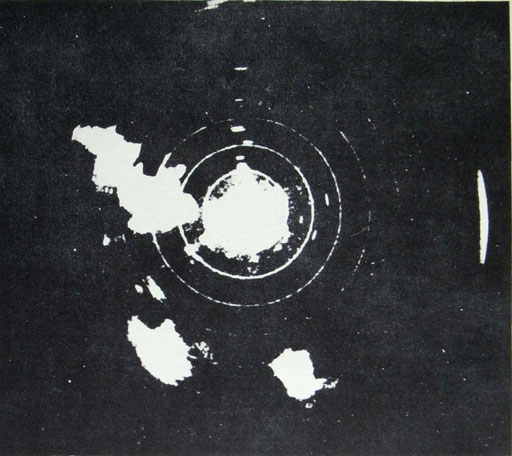

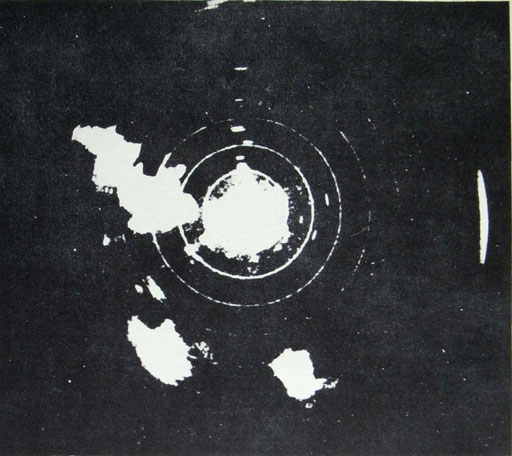

Figure 26.--Radar echo from a thunderstorm on the PPI scope (40 mile sweep with 5 mile markers). Scanning in elevation disclosed the vertical extent of this storm to be 40,000 foot. (S-band system). Right lenticular spot at the outer edge of the circle is 0° azimuth. Irregular large bright area at azimuth 190° is thunderstorm.

C. WEATHER INFORMATION FROM RADAR

Useful weather information can be obtained from radars, which does not replace but merely supplements the regular aerological data.

Radar operators can distinguish weather indications by the saturation and the unsteadiness of the echo on the A-scope, the shape and brightness on the PPI and by the elevation angle limits.

The following are PPI characteristics of various weather types:

--18--

1. A thunderstorm echo--bright, dense central area with indistinct boundaries.

2. A convective cloud echo--scattered as in a random manner, moving with direction and velocity of the general circulation.

3. An orthographic thunderstorm echo--will show little geographic movement.

4. A cold front echo--usually arranged in a line.

5. A warm front echo--hazy and usually covers very wide area.

6. A line squall echo--long, narrow, and moves rapidly.

7. A shower echo--generally less intense than thunderstorm with a hazy structure.

The lower frequency (meter wave) radars rarely are of much weather help, though they may occasionally detect heavy rain storms.

D. WEATHER AND STATIONING OF THE CAP

The altitude and disposition of CAP may depend very largely on the latest pilot report concerning "mattress," "quilt," "blanket," and "pillow." In good visibility the controller puts the CAP at normal stations, but if clouds exist, he may have to keep some planes above cloud cover and some below for a sound defense of the force.

Heavy winds aloft combined with cloud cover also affect the stationing of the CAP. Such conditions make it difficult for the planes to hold their stations. Therefore, wherever possible, the CAP should be placed where it can maintain visual contact with the base. If it is necessary to keep planes at very high altitudes or out of sight contact, the controller must constantly track his planes on a PPI to prevent them from drifting off station.

All pilots must learn the proper use of YE-YG/ZB and other homing equipment for keeping station when visibility is reduced. By careful tuning of ZB gear an experienced pilot can maintain an assigned position within a YE-YG letter sector. Alternatively he may fly a short patrol line across two or three sectors. In neither case is sight contact necessary even though his base may be a carrier under way.

Planes equipped with air-borne radar may use that gear to assist in keeping station.

E. WEATHER AND INTERCEPTION

When conducting an interception, the controller depends on his CAP for weather reports--particularly visibility and the presence of cloud layers or stacks--in the immediate vicinity. If all is clear, his primary concern is the utilization of any advantage the sun might produce. When the enemy has been discovered to be*a group of planes, and if it does not complicate an otherwise simple interception, interception should be from a position up-sun with 3 to 4 thousand feet altitude advantage. When the enemy is a single plane, the altitude advantage may be lessened so as to increase the chance of making a tallyho.

On the basis of local CAP reports, the controller must keep all pilots informed of radical weather change at the base.

Cloud conditions may vary on different bearings and at different ranges and altitudes.

If the flight leader knows the bogey's height and bogey s range, he is the best judge as to how a cloud formation or weather front should be handled, reporting action taken to the controlled.

F. STACKING OF COMBAT AIR PATROLS

The presence of cloud layers or frontal conditions greatly complicates the controller's problems. Utilizing the best altitude estimates of approaching enemy planes and his picture of cloud and visibility conditions, he must decide whether to send his fighters above or below a cloud layer, to split them, or to control them through the clouds.

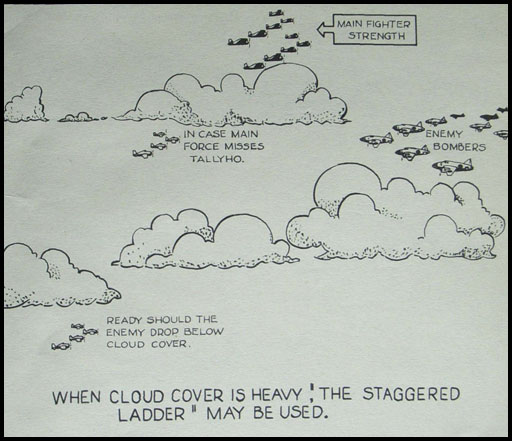

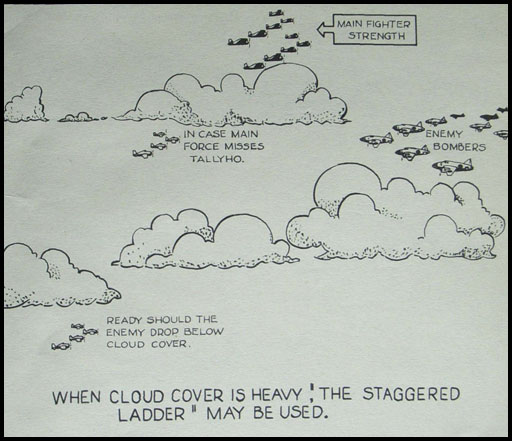

As the enemy continues to develop and to exploit his knowledge of our radar characteristics and limitations along with the advantages clouds provide him, it has been found necessary to disperse defensive fighters in altitude, bearing, and range when intercepting sizeable enemy groups. Such dispersion may be known as "a staggered ladder" in which the greatest number are generally at the best estimated intercepting altitude and most directly in line with the incoming enemy.

Backing up these fighters is a second group flying somewhat astern of and below the lead

--19--

RADAR SCOPE SHOWS TYPHOON MOVEMENT OVER 4% HOUR PERIOD

This picture was taken at 1100 at which time the center of the typhoon was 39 miles distant, bearing 077° (T). Wind was 57 knots, with gusts to 66 knots. Ceiling was less than 500 feet; visibility, 800 to 1,200 yards. The sea was very high--20 to 40 feet. |

Taken at 1200, this picture shows the typhoon center 40 miles distant, bearing 055° (T). Wind in gusts exceeded 75 knots from 315° (T). Ceiling was less than 500 feet, and visibility 600 to 1,000 yards. Seas were very high to mountainous----40 feet plus. |

At 1300 the storm was nearest the ship which submitted this record. The center was 35 miles distant, bearing 026° (T). Wind in gusts exceeded 75 knots. Ceiling and visibility were practically zero-zero. Seas were high and mountainous-40 feet plus. |

The picture taken at 1530, shows the circular cloud and precipitation pattern of the typhoon, the center of which is now off the scope. Winds were 41 knots with gusts to 60 knots from 250° (T). Ceiling was 7,000 to 8,000 feet with isolated cloud patches at 1,000 feet. Visibility ahead was 6,000 yards; astern, 1,000 yards. Seas were high--12 to 20 feet. |

| Figure 27.--Typhoon on the PPI scope. |

--20--

group and generally below any intermediate cloud layers (this group may be split to cover top and bottom of clouds). The controller uses these to strike any enemy planes which split and come down from the initial group. They may be ordered merely to assume a "backstop" station and pick off whatever they see; or, if the radar picture is sufficiently clear, they may be controlled on interceptions.

A third group of fighters (if available), generally the smallest in number, may be sent out behind the other two groups at low altitude to intercept whatever enemy planes have thus far escaped and are pressing in their attack on our forces. This group normally flies below the lowest cloud layer or at a maximum altitude of not over 3,000 feet.

This is one type of group deployment which may serve as a guide. Others may be devised to fit the needs of the particular weather and visibility conditions.

G. INTERCEPTING A SINGLE BOGEY

If a single bogey is thought to be taking advantage of scattered clouds, cloud banks, or layers, a division can be utilized as a single unit, or can be split in two sections and used to cover simultaneously the top and bottom of the cloud formation. In such disposition the division may still be controlled as a unit or each

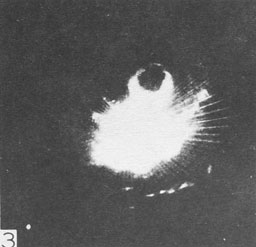

Figure 28.--The "staggered ladder."

--21--

section may be controlled separately and joined up at the completion of the interception.

H. WEATHER AND THE CONTROLLED INTERCEPTION

Working against cloud or haze conditions, the lighters may heed close control. A "head-on" interception is a good visibility interception, and the chances of tactical surprise are greatly enhanced if tactical use is made of the sun, i.e., if the controller interposes his fighters between the enemy and the sun. When visibility is restricted, it may be necessary to employ a "controlled" interception in which the controller places his fighters in the most strategic position to sight and initiate attack against the enemy.

Enemy aircraft often approach through a front or through stacked clouds. If it is not feasible to have friendly fighters go on through to complete the interception, the fighters may be orbited at the most likely position the bogey is expected to break through. As soon as he does emerge, the fighters should be in a position to tallyho and attack.

I. WIND AND LANDING

Winds always affect landing and launching operations. This effect is minimized, in fast carrier forces by their having sufficient available speed. Other forces with less available speed (i.e. CVE's) are adversely affected by lack of wind. This is overcome by the use of the catapult when necessary. When night fighters are to be landed, it is necessary to inform them of velocity and direction of the wind even though the ship may be on a landing course.

--22--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (2)

Next Chapter (4)