Chapter 6

SIXTH PERIOD

AIRCRAFT DEFEAT U-BOATS ATTEMPTED COME-BACK AND

FORCE ADOPTION OF MAXIMUM SUBMERGENCE

JULY 1943 - MAY 1944

AS A RESULT of the heavy losses they experienced in their battle against the North Atlantic convoys during the previous period the U-boats

withdrew from the North Atlantic and temporarily abandoned their wolf-pack tactics. After a marked lull in U-boat activity in June, the enemy

made his first, and most strenuous, effort to regain the initiative in July 1943. The 85 U-boats at sea in the Atlantic were widely dispersed

and simultaneous campaigns were conducted in regions that had been soft spots for the U-boats in the past, such as the Caribbean, Brazilian,

and Freetown Areas. To withdraw from the strategically important North Atlantic was a confession of defeat, but the enemy must have anticipated

a rich harvest from surprise attacks in comparatively lightly protected areas.

If so, the enemy was probably sadly disappointed. World-wide shipping losses as a result of U-boat action in July were only 44 ships of

244,000 gross tons, considerably less than the monthly average during the preceding period. The heaviest losses occurred in the Indian Ocean,

mostly in the Mozambique-Madagascar Area, where 15 ships of 82,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats while no U-boats were sunk. This was the

highest monthly total of the war for shipping losses to U-boats in the Indian Ocean. About six German U-boats of the 1200-ton U-Kreuzer class

were probably responsible for most of these sinkings.

About 15 U-boats operated in the Caribbean Sea and off the Brazilian coast as far south as Rio de Janeiro. They sank 19 ships during July,

but were forced to pay a heavy price for these successes as nine U-boats were sunk by shore-based aircraft in these areas. This eliminated

another soft spot from the list of areas where U-boats felt they could operate safely.

July 1943 was marked by the successful invasion of Sicily, which took place without the loss of any shipping to U-boats. Only five ships

were sunk by U-boats in all of the Mediterranean at the cost of seven U-boats sunk by the Allies.

Despite the meager results achieved, the U-boats suffered the heaviest losses of the war in July 1943 as the world-wide total of U-boats

destroyed during the month reached 46. This was the first month of the war in which the number of U-boats sunk exceeded the number of merchant

vessels sunk by U-boats. Of the 46 U-boats sunk during July, 37 were destroyed in the Atlantic where aircraft experienced their greatest successes

of the war. Shore-based aircraft destroyed 28 U-boats in the Atlantic while carrier-based aircraft accounted for another six. The aircraft from

the U. S. escort carriers operated in regions outside the range of shore-based aircraft and were able to prevent the U-boats from achieving any

successes in their attacks against the mid-Atlantic convoys. These attacks by carrier-based aircraft must have finally convinced the U-boats

that they were no longer safe from air attack anywhere in the Atlantic.

Allied antisubmarine forces inflicted the greatest damage on the enemy in the Bay of Biscay and its approaches as 14 U-boats were sunk in

the Biscay-Channel Area and another six in the Gibraltar-Morocco Area. Although aircraft crews had to face the increased antiaircraft fire of

surfaced U-boats proceeding in formation during the daytime, this presented them with a large proportion of Class A targets and over 25 per

cent of the attacks resulted in the sinking of the U-boat. The crowning success of the month occurred on July 30 when a whole group of three

outward bound U-boats was sunk, two by Coastal Command aircraft and the third by the Second Escort Group. Two of these three U-boats were

supply U-boats, and this plus the loss of two other supply U-boats elsewhere severely curtailed later U-boat operations. This incident was

also marked by one of the odd coincidences of the war when U-461 was sunk by the Sunderland aircraft U/461.

--44--

Four additional U-boats were sunk in the Bay of Biscay by Coastal Command aircraft during the first two days of August, and the U-boats were

forced to change their tactics in making the transit of the Bay. They reverted to surfacing at night for the minimum time necessary for the charging

of batteries and, in addition, hugged the coast of Spain to get as far as possible from Allied air bases.

The more cautious tactics adopted throughout the Atlantic in August 1943 marked the failure of the first attempted come-back by the U-boats. Only

four ships were sunk by U-boats in the Atlantic during the month, all during the first week of August and all south of the Equator. The world-wide

shipping losses to U-boats in August were only 15 ships of 87,000 gross tons as the U-boats sank six ships in the Indian Ocean and five in the

Mediterranean.

The average number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic during August declined to about 60, and most of them were homeward bound by the end of

the month. There was no doubt that, as a direct consequence of the loss of a number of supply U-boats and also of the heavy losses suffered by

U-boats in the operating areas, the campaigns in the Caribbean and Brazilian Areas were curtailed, and the U-boats returned to base about two

weeks earlier than they would otherwise have done.

The number of U-boats sunk during August continued to be satisfactory, considering the smaller number of targets available and the more

cautious tactics adopted by the U-boats. Aircraft attacks accounted for 18 of the 25 U-boats sunk throughout the world. Aircraft from the USS

Card turned in a particularly notable performance by sinking five U-boats during the month. New evidence of the gradual disappearance of all

soft spots was indicated by the sinking of three U-boats in the Caribbean-Brazilian Area and two U-boats in the Freetown Area. One U-boat was

also sunk in the Indian Ocean, the first in 1943.

As the lull in U-boat activity continued during August and the first three weeks of September, the Allies attempted to maintain the initiative

by carrying the battle into the Biscay transit areas. Escort groups were moved closer to the Spanish Coast in an effort to sever the new U-boat

routes. However, Germany reacted strongly to this new threat, bringing out a new weapon, the radio-controlled, jet-propelled glider bomb. These

were released by German bombers against the escort groups in the Bay. HMS Egret was sunk by this new weapon late in August and two other ships

were damaged. The escort groups were withdrawn from the Bay offensive in September, as a result of these attacks and renewed U-boat activity in

the North Atlantic.

This resumption of the battle against the vital North Atlantic convoys marked the second attempt of the U-boats to regain the initiative. It

was on September 19, 1943, that it first became evident that Convoys ONS 18 and ON 202 were being shadowed by U-boats. That night, attacks developed

against both convoys, but the escorts of ONS 18 were able to drive the U-boats off without suffering any losses.

Convoy ON 202 was attacked later that night and HMS Lagan was torpedoed. This was the first ship torpedoed in the Atlantic in September. It was

also the first indication that the U-boats were using a new weapon, the acoustic homing torpedo (Gnat or T-5). HMS Lagan had been detached to follow

up an HF/DF bearing and had obtained a radar contact which faded when the range was about 3000 yards. She was within about 1200 yards of the assumed

diving position when she was hit by a torpedo which blew off her stern. She was taken in tow and reached harbor. In the morning two merchant ships

of Convoy ON 202 were also torpedoed.

During the forenoon the two convoys were ordered to join, forming one convoy of 63 ships and about 15 escorts. That evening two escorts were

sunk, one while hunting a U-boat, the other while following up a radar contact. Despite these losses, the attempts which the U-boats made on the

convoy during the night failed. Early on the 21st, the convoy was rerouted to the southward in order to get within range of Newfoundland-based

aircraft. However, heavy fog prevented much air cover that day and also hampered the U-boats. The U-boats, estimated to be 15 or 20 in number,

had the worst of it that night. Thanks to HF/DF fixes by the escorts, the U-boats were prevented from sinking any ships and in the early hours

of the 22nd, one of the pack was rammed and sent to the bottom by HMS Keppel.

Liberators gave cover throughout the day but the convoy was rather opened up by night and the U-boats again attacked in strength. Just before

midnight one escort was sunk, later three merchant vessels were torpedoed and one more ship was sunk early that morning. The U-boats kept in

contact with the convoy during the 23rd, but the attacks made by escorting Liberators from Newfoundland so deterred

--45--

|

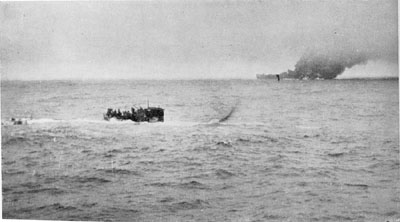

FIGURE 1. Bombs explode close aboard in attack by aircraft from USS Card, August 7, 1943, off

the Azores. Note antiaircraft guns. |

them that their attacks that night were halfhearted and they lost contact with the convoy next day.

In all, six merchant vessels and three escorts had been sunk, and another escort damaged. Three U-boats were sunk, two by covering aircraft and

one by an escort. Although heavy losses were inflicted on the escorts by the acoustic torpedo, on only three occasions did U-boats succeed in firing

torpedoes at the convoy. The U-boats were more reluctant then ever to press home their attacks, and as soon as they were detected, they made every

effort to escape, either at high speed on the surface or by going deep. HF/DF was again of great value in determining the direction of impending attacks.

The actual results of this battle would probably have proved disappointing to the enemy but captured documents indicate that the U-boats greatly

overestimated the damage inflicted by the acoustic torpedoes. In addition, they felt that the heavy fog was largely responsible for saving the convoy

from much heavier losses. This probably accounts for the greatly increased effort they made against the North Atlantic convoys in October 1943.

The world-wide shipping losses to U-boats in September were 20 ships of 119,000 gross tons, only slightly higher than the August losses. In

addition to the six ships sunk in the North Atlantic, two were sunk in the Brazilian Area, six in the Mediterranean and six in the Indian Ocean.

About five German U-boats appeared to be responsible for the sinkings in the Indian Ocean and there was evidence that they were using Penang as a

temporary base. The more cautious tactics of maximum submergence served to reduce the number of U-boats sunk during

--46--

|

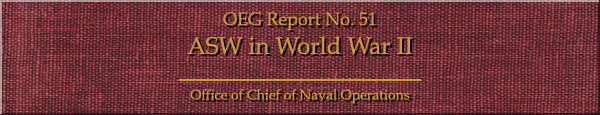

FIGURE 2. Crew of U-664 abandon ship after attack by aircraft from USS Card, August 9, 1943;

U-boat is settling by the stern, and life-rafts are visible at the right. |

September to only 10. By the end of September 1943, however, the Italian Fleet had surrendered, and 29 Italian U-boats had come under Allied

control.

Encouraged by their supposed successes in September, the U-boats increased their attack against the North Atlantic convoys. The downward trend

in the number of U-boats at sea was reversed, and there were about 75 U-boats at sea in the Atlantic in October as compared to only about 50 in

September. Over 40 U-boats were concentrated in the Northwest and Northeast Atlantic Areas and the days of wolf-pack attacks on convoys seemed

to have returned.

However, this time the U-boats suffered a much more decisive defeat than the one they had experienced in May 1943. First of all, the U-boats

had trouble in locating Allied convoys because of evasive routing, and they were able to inflict losses on only three of the North Atlantic convoys

during October. Then again, the U-boats were not attacking with the same aggressiveness they had shown in the past, and they were able to sink only

three merchant vessels and one escort. Moreover, the U-boats had to pay the prohibitive price of over seven U-boats sunk for each merchant vessel

sunk as 22 U-boats were sunk during October in the Northwest and Northeast Atlantic Areas. Aircraft played a major part in this decisive setback of

the U-boats destroying 17 of the 22 U-boats sunk in these areas. Carrier-based aircraft accounted

--47--

for six of these 17 U-boats with four of the kills due to aircraft from the USS Card. In two cruises, aircraft from the USS Card had made 19

attacks, nine of which resulted in A or B assessments. This second cruise closed with the gallant action in which the USS Borie, one of the escorts

of the USS Card, was lost.

On the night of October 31, after having severely damaged one U-boat reported by a plane from the USS Card, the USS Borie made radar contact with

another U-boat. Sonar contact was obtained and a depth-charge attack brought the U-boat to the surface. The U-boat tried to escape on the surface,

but the Borie opened fire and then rammed the U-boat at 25 knots, riding over the U-boat's forecastle and pinning it under. The two ships remained

in this position for about 10 minutes with the U-boat exposed to fire from the Borie's 4-inch and 20-mm guns, Tommy guns, revolvers, rifles, and

shotguns. One of the U-boat's crew was killed by a sheath knife thrown from the Borie's deck while another was knocked overboard by an empty 4-inch

shell case. At length, the U-boat got under way, with the Borie, now severely damaged, in full pursuit maintaining gunfire. A torpedo was fired at

the U-boat but missed. The range was then closed again and, as the attempt to ram failed, three depth charges were fired straddling the U-boat.

Another torpedo was then fired passing within 10 feet of the U-boat's bow. A main battery salvo struck the U-boat's diesel exhaust and the U-boat

immediately slowed, stopped, and surrendered. About 15 members of the crew abandoned ship and the U-boat sank stern first. The entire action from

the initial contact until the U-boat sank lasted one hour and four minutes. Unfortunately, the ramming resulted in serious damage to the Borie and

she had to be abandoned later in the day.

The world-wide shipping losses to U-boats in October were about the same as in September. Only 20 ships of 97,000 gross tons were sunk, but the

number of U-boats sunk increased to 27 reflecting the increased U-boat activity. The U-boats were forced to disengage again in their battle against

the North Atlantic convoys and their second attempt at a comeback had failed. The first promising results of the acoustic torpedo were not maintained,

and during October this new weapon had singularly little success. By way of countermeasures the Allies developed a towed noise-making device (U. S.

FXR - British FOXER) and new step-aside tactics in attacking U-boats. By the end of October the British had been granted the use of the Azores by Portugal,

and air bases were immediately established greatly extending Allied air coverage of the Atlantic.

A fundamental change in U-boat tactics was observed in November 1943 as the U-boats made their third, and most feeble, attempt to regain the initiative.

As a result of the heavy losses inflicted on the U-boats by aircraft in October, and also influenced by the Allied air bases on the Azores, the U-boats

were compelled to adopt a mode of existence which favored their survival rather than the most effective employment against shipping. In order to favor

their chances of survival, the U-boats remained completely submerged during the daytime, thereby avoiding Allied air patrols. They surfaced at night to

charge batteries and to follow-up and attack any convoys within reach. Small groups of U-boats were disposed along the probable course of the convoy,

about one (lay's run apart, so that each pack would be able to attack the convoy for only one night. To compensate for this loss of mobility of the

U-boats, enemy long-range reconnaissance aircraft were used to locate our convoys and to pass on information to the U-boats.

As most of the enemy's long-range aircraft were based in France, these new U-boat tactics were tried out on the convoy route between the United

Kingdom and Gibraltar. Four north-bound convoys were attacked by the U-boats with very little success, as only one ship was sunk while several U-boats

were destroyed. Fortunately, the attacks on these convoys came after Allied aircraft had moved into the Azores and strong support by both escort groups

and shore-based aircraft brought the convoys safely through the concentrations of U-boats. These attacks also provided Azores-based aircraft with their

first kill as a Flying Fortress sank a U-boat at daybreak on November 9.

After the failure of this third attempt at staging a come-back the U-boats reconciled themselves to remaining on the defensive for the remainder of

this period. The world-wide shipping losses to U-boats dropped to their lowest level since Pearl Harbor as only 13 ships of 67,000 gross tons were

sunk during November 1943. There was a spurt of activity in the Panama Sea Frontier as three ships and one schooner were sunk by U-boats. Not a single

ship was sunk in the North Atlantic Convoy Area during the month, while four ships were sunk in the Indian Ocean and three in the Mediterranean. German

aircraft, making

--48--

extensive use of torpedoes and glider bombs, had become a greater menace to the Mediterranean convoys than were the U-boats. Aircraft sank seven

ships of over 60,000 gross tons in the Mediterranean during November, six of them off the coast of North Africa between Iran and Bizerte. Early in the

month, the enemy's attempt to reinforce the diminishing number of U-boats in the Mediterranean was largely frustrated as three of the five U-boats making

the attempted entry were sunk.

In all, 18 U-boats were sunk during November, about half by aircraft and half by surface craft. These U-boat kills were rather widely distributed. The

Second Escort Group sank two U-boats using a creeping attack. This method of attack was developed to take care of deep U-boats and involved one ship's

keeping contact with the deep U-boat at a distance and directing the attacking ship onto the unsuspecting U-boat. The attacking ship proceeded silently

at slow speed in order to surprise the U-boat before it could start any violent evasive maneuvers. When the attacking ship was over the U-boat, it would

drop a large pattern of depth charges.

Two large U-boats, apparently headed for the Indian Ocean, were sunk in the South Atlantic during November by U. S. aircraft based on Ascension Island.

These sinkings were particularly valuable as the Indian Ocean was one of the few remaining areas where the exchange rate was still favorable to the U-boats.

The sinking of a U-boat headed for the Indian Ocean might be considered equivalent to the saving of ten ships, which the average U-boat would probably sink

in the Indian Ocean before it itself would be sunk.

Barrier patrols by aircraft in the South Atlantic paid off during the last week of December 1943 and the first week of January 1944. Five enemy merchant

vessels attempted to return from Japan to Germany and were in the South Atlantic heading north. One of the five enemy blockade runners made port, badly

damaged, three were sunk by ships and aircraft of the Fourth Fleet in the Brazilian Area, and another was sunk by British-based aircraft in the approaches

to the Bay of Biscay. This was the last attempt the enemy made to run the blockade with merchant vessels, but U-boats continued to make occasional trips

between Germany and Japan.

World-wide shipping losses to U-boats stayed at the same low level as only 13 ships of 87,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats in December 1943. Although

over half of the 60 U-boats at sea in the Atlantic were concentrated in the North Atlantic Convoy Area, not a single ship was sunk there. All the sinkings

were due to small numbers of U-boats operating in distant areas. Five ships were sunk in the Indian Ocean, three in the Freetown Area, and one in the

Mediterranean. The other four ships were stink in American coastal waters extending from Cape Hatteras to Aruba. However, the U-boats' policy of remaining

submerged during the daytime re-sulted in only seven U-boats being sunk during December, the lowest monthly total in 1943.

The shipping losses to U-boats in December were overshadowed by the surprise air attack on Bari Harbor, on the east coast of Italy, on December 2.

This attack, made by about 25 bombers, resulted in the loss of 16 ships and damage to 10 others. The heavy losses were due in part to the explosion of

several ammunition ships.

The U-boats sank only 13 ships of 92,000 gross tons in January 1944. Two of these ships were sunk from North Atlantic convoys. Three ships were sunk

in the Barents Sea Area from a convoy headed for Russia while eight ships were sunk in the Indian Ocean. The main concentration of about 25 U-boats in

the North Atlantic moved gradually eastwards, towards the west coast of Ireland, in an apparent attempt to locate Allied convoys. This move did not

succeed as no ships were sunk in the Northeast Atlantic Area while seven U-boats were destroyed there. However, only 11 U-boats were sunk in January

as the U-boats continued their cautious tactics of maximum submergence. Fear of the impending invasion may have played its part in keeping the U-boats

within short range of the French coast.

February 1944 marked the fourth successive month in which fewer than 20 ships and less than 100,000 gross tons of shipping were sunk by U-boats.

Only 18 ships of 93,000 gross tons were sunk during the month, ten of them in the Indian Ocean, six in the Mediterranean, and only two in the Atlantic,

one near Iceland and one in the Freetown Area. About half of the 60 U-boats at sea in the Atlantic were concentrated in the North Atlantic, west of the

United Kingdom. However, the North Atlantic convoys passed through this concentration of U-boats without suffering any losses while severe losses were

inflicted on the U-boats. The world-wide total of U-boats sunk mounted to 22 in February, as ten were destroyed in the Northeast Atlantic Area.

--49--

|

FIGURE 3. Crew of U-550 prepare to abandon ship after attack by USS Joyce, Gandy and Peterson,

200 miles off New York, April 16, 1944. SS Pan Pennsylvania burning in the background. |

The outstanding achievement of the month was the 27-day patrol of the Second Escort Group, in the course of which six U-boats were sunk in a period

of 20 days. Every U-boat contacted was hunted to destruction. Four hours and 106 depth charges were required, on the average, to kill each of these six

U-boats. Combined creeping and follow-up attacks were responsible for the destruction of four of them. Against these successes must be recorded the loss

of HMS Woodpecker to an acoustic torpedo. In contrast to these attacks, HMS Spey, fitted with the latest type of Asdic gear including the Q attachment

and the Type 147B depth predictor, destroyed two U-boats in two days, each in a matter of minutes. Single patterns of ten depth charges forced the U-boat

to the surface in each case.

Another outstanding feature of the month's operations was the first sinking of a U-boat as the result of an initial MAD contact. U-boats had, during

the previous months, approached on the surface at night and passed through the Straits of Gibraltar in the daytime entirely submerged. They made only

enough speed to maintain trim, while the current carried them through. Allied ships, operating in the Straits, faced bad sound conditions, because of the

variation in the density of the water. Echo ranging was unreliable and listening was not of much value either, as the U-boats proceeded at very slow speeds.

This situation presented an ideal set-up for the use of MAD. An MAD barrier patrol was started across the Straits in January 1944, in order to prevent

the submerged passage of U-boats into the Mediterranean. Two PBY's of VP63 were flying on this patrol on February 24 when an MAD contact was obtained.

Shortly afterward, two British destroyers and other planes arrived on the scene. The U-boat was attacked with retro-bombs from the MAD planes, depth charges

and gunfire from the destroyers, and depth bombs from the other aircraft before it was destroyed. This MAD barrier patrol probably destroyed another U-boat

attempting to make the passage in March.

During March 1944 there were some signs of the breaking up of the concentrations of U-boats in favor of a general dispersion across the North Atlantic

convoy lanes. There was an increase in the shipping losses to U-boats as 23 ships of 143,000 gross tons were sunk throughout the world. Losses were again

heaviest in the Indian Ocean where 11 ships were sunk, but the German U-boats operating there were seriously inconvenienced by the sinking in the South

Indian Ocean of two tankers which had been refueling

--50--

|

FIGURE 4. U-550 sinks. |

them. No ships were sunk in the Indian Ocean during the remaining two months of this period. Seven ships were sunk in widely scattered parts

of the Atlantic in March, four in the Mediterranean, and one in the Barents Sea Area.

The number of U-boats sunk increased for the third successive month as 23 U-boats were destroyed in March, the same as the number of ships sunk

by U-boats. Two of the longest U-boat hunts of the war occurred at about this time, one lasting 30 hours and the other 38 hours before the U-boats

were destroyed. The Second Escort Group accounted for two more U-boats in March, bringing its total up to 14. One of these was sunk with the cooperation

of aircraft from the escort carrier, HMS Vindex.

The escort carrier groups contributed greatly to the campaign in March, sinking nine U-boats in the Atlantic. Aircraft from HMS Chaser, using rockets,

participated in the sinking of three U-boats. Aircraft and escorts of the USS Bogue participated in the sinking of one U-boat while two other U-boats

were sunk by escorts of the USS Block Island. Toward the latter part of the month, the USS Block Island task group, operating in a probable refueling

area near the Cape Verde Islands, sank two more U-boats. Sono-buoys were used in this operation.

In the Mediterranean, the enemy lost five U-boats out of the comparatively small number remaining there. Two of these were sunk in a raid by U. S.

Army Liberators on the U-boat base at Toulon. The lack of sightings in the Bay of Biscay caused Coastal Command to send its aircraft closer to the French

coast and a U-boat was probably sunk by hits from 6 pounder gunfire from a Mosquito. A Catalina from Capetown sank a U-boat about 400 miles south of the

Cape of Good Hope.

The average number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic dropped to 50 in April 1944 as the enemy continued to conserve his U-boats in anticipation of a

major effort against the threatened invasion. U-boat patrol dispositions were rather sparse and wide-flung and great importance seemed to be attached to

the gathering of meteorological information, in aid of military and air planning. Only nine ships of 62,000 gross tons were sunk by U-boats during the

month, seven in the Atlantic and two in the Mediterranean.

For the first time in 14 months, not a single ship was sunk by U-boats in the Indian Ocean. However, the most disastrous event of the month occurred

there, when on April 14 an ammunition ship exploded in Bombay harbor, completely destroying 14 ships and damaging nine others. As partial compensation

--51--

for this disaster, the world-wide losses due to enemy action reached a new low for the war as only 13 ships of 82,000 gross tons were stink in April.

Starting in April, the U. S. ocean escorts of the UGS convoys continued past Gibraltar into the Mediterranean as far as Bizerte before being relieved

by British escorts. Each of these three April convoys was subjected to the familiar Nazi air attack near Algiers as a result of which three ships were

sunk and five damaged.

On the night of April 20, the Germans made an unsuccessful attack with human torpedoes at Anzio, and both prisoners and craft were taken. These craft

consisted of two torpedoes, one mounted about 6 inches above the other. The "mother" (upper) torpedo was modified to hold a human pilot who guided the

craft and released the normal lethal torpedo attached underneath when within firing range.

Considering the inactivity of the U-boats, it was remarkable that 16 of them were sunk during April. The escort carrier groups accounted for six of these.

The average number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic declined to only about 40 in May 1944. However, a large number of U-boats, which normally would

have been operating in the Atlantic, was apparently being held in Biscay ports and in Baltic and Norwegian ports for use against the forthcoming invasions.

World-wide shipping losses to U-boats were lower than they had ever been before as only four ships of 24,000 gross tons were stink by U-boats during May.

Three of these ships were sunk in the Brazilian Area and one in the Mediterranean. Total shipping losses from all causes also dropped to a new low as only

12 ships of 40,000 gross tons were lost during May.

The most notable achievement of the U-boats during May was the sinking of the escort carrier, USS Block Island. Early in the month one of her planes

assisted while the USS Buckley, one of her escorts, finished off a German U-boat after a short (16 minutes) but thrilling surface engagement involving

gunfire and ramming. On May 29, while the task group was searching for a U-boat suspected to be in the vicinity, the Block Island was struck by three

torpedoes in a short interval. One of the escorts had her stern blown off. Shortly thereafter, the other escorts made contact with the U-boat and probably

sank her after two Hedgehog attacks. The gallant career of the Block Island came to an end later in the day when she had to be abandoned.

Despite the enemy's attempt to conserve his U-boats for the imminent invasion, the number of U-boats sunk during May 1944 was 29, the highest figure

since the record total of 46 in July 1943. The leading area in the sinking of U-boats during May was the Northern Transit Area, East, where ten U-boats

were destroyed during the month, nine of them by aircraft. Three of these were sunk by aircraft from HMS Fencer which was escorting a convoy from Russia

in the early days of the month. During the latter part of May, a considerable increase was noted in the number of Baltic U-boats en route to the Atlantic

via the Iceland-Faroes passage. For some time past the operations of Allied submarines against enemy shipping in Norwegian waters had prevented aircraft

from making sweeps in this area. The enemy may have thought that he could safely relax his precautions in this area as many of these U-boats were traveling

on the surface. Coastal Command aircraft quickly exploited this soft spot, sinking six U-boats during the latter part of the month.

The small number of U-boats in the Mediterranean was further depleted as four U-boats were destroyed there in May while another was sunk while attempting

to pass through the Straits of Gibraltar. This was the third successful attack on a U-boat as a result of an initial MAD contact. The four successful attacks

in the Mediterranean demonstrated the importance of persistence and the value of close cooperation between air and surface units. Three of the four hunts

involved aircraft as well as surface craft and the durations of the actions ranged from 22 hours to 76 hours. This record action, which began on May 14,

was culminated on the 17th with the sinking of a U-boat after a continuous hunt of 76 hours involving eight ships and three planes. The U-boats in the

Mediterranean fought back strenuously, sinking one merchant vessel and two escorts and damaging four other ships during the month.

The outstanding event of the month, and probably the outstanding achievement of the U-boat war by a single ship, was the performance of the destroyer

escort, USS England, in the Pacific from May 19, 1944 to May 31. During this brief period, the USS England destroyed five Japanese U-boats and was assigned

the major credit in the destruction of a sixth U-boat. The Hedgehog was the primary weapon used in achieving these results. This series of attacks resulted

from the suspicion that a force of about five Japanese U-boats was patrolling the line of the Equator, to the

--52--

northeast of the Admiralty Islands. The USS England was accompanied by USS George and Raby when they swept through this area. The outstanding

performance of the England is the more remarkable in that it was her first contact with the enemy.

There was some credible evidence from aircraft sightings and attacks in the final week of May 1944 that two or more U-boats were at sea in the

Western English Channel, off the French coast. This proved to be a preview of the nature of U-boat operations in the next period as, for the first

time since the early days of the war, the U-boats returned to the hazardous shallow coastal waters in the vicinity of England. This operation was

possible only because the U-boats could take advantage of the use of Schnorchel and thereby reduce their exposure to aircraft attacks.

| 6.2 |

COUNTERMEASURES TO THE U-BOAT |

During this period, the U-boats tried several modifications of their previous wolf-pack tactics in an effort to gain the upper hand in their

attacks on Allied convoys.

The first modification in tactics was made in September 1943 in the attacks on the North Atlantic convoys. It was based on the use of the acoustic

torpedo and involved attacking the escorts first, with the objective of reducing the convoy defenses to a point where the merchant vessels would become

easy prey for the U-boats. Although some escort vessels were sunk, the objective was never accomplished; because at this stage of the war the Allies were

using a larger number of escorts with the convoys and had a sufficiently large number of antisubmarine ships available that the loss of a few escorts

would not seriously handicap future convoys. These U-boat tactics might have proved more effective in the early days of the war when the number of

antisubmarine ships available to the Allies was extremely limited.

The second modification was made in November 1943 in the attacks on the convoys between Gibraltar and the United Kingdom. This change in tactics

was forced on the U-boats by the heavy Allied air coverage of the North Atlantic which prevented the U-boats from operating on the surface in the

daytime and thereby prevented the concentration of a large number of U-boats around a convoy. The tactics adopted by the enemy involved stationing

small packs of U-boats along the path of the convoy. Long-range aircraft from Bordeaux were used to shadow Allied convoys during the day. Reports of

the air reconnaissance were passed on to the U-boat packs, which then attempted to maneuver into a favorable position for a night attack. This change

in tactics came a little late, too, since flying facilities had become available in the Azores in October 1943. Several convoys were intercepted by the

U-boats, but strong support by escort groups and land-based aircraft brought the convoys safely through with only negligible damage.

The third modification in U-boat tactics, made after the setback in November 1943, involved the almost complete abandonment of the old, highly

organized wolf-pack attacks. Concentrations of U-boats were still maintained in the North Atlantic but attacks were generally made by individual U-boats

who happened to find themselves in a favorable position to attack a convoy. Although these U-boat tactics were much less effective against Allied

shipping, they did enable the U-boats to remain submerged during the daytime. The scarcity of supply U-boats may have also been a factor in this drastic

modification of wolf-pack tactics, which had been predicated on high-speed surface operations of the U-boats, requiring high fuel consumption.

These futile attempts by the U-boats had very little success. Only about six ships a month were stink by U-boats from Allied convoys. The tonnage sunk

from convoys by the U-boats was only about 40 per cent of the total tonnage stink by them. The degree of safety reached by convoyed shipping during this

period is well illustrated by the experiences of the North Atlantic trade convoys (HX, SC, ON, ONS). Of the 900 ships that sailed monthly in these convoys,

only about 1 1/2 were sunk each month by U-boats. This represented a loss rate of only about one sinking per 600 transatlantic trips. This high degree of

safety from U-boats was typical of the other convoy systems as well.

One of the primary reasons for the ineffectiveness of the U-boats against Allied convoys was poor U-boat morale, as evidenced by their failure to press

home attacks on convoys once they were detected. It is not difficult to see the reasons for this lack of aggressiveness. In the early months of 1943,

Allied bombers had reduced the Biscay ports to heaps of stones. Though they could not get at the U-boats in their shelters, these raids deprived the

U-boat crews

--53--

of all but the most primitive facilities after they had come back, through continually mined waters, from long, exhaustive, dangerous, and now

unsuccessful patrols. To reach the North Atlantic, the U-boats had to proceed submerged through the Bay of Biscay for the first five or six days of

their patrol, surfacing for only a few hours after midnight. To find the convoy, the U-boats had to pass through the areas remorselessly swept by

covering aircraft, and when the U-boats sighted the convoys, they found more numerous and better equipped escorts manned by more highly trained crews.

An analysis of attacks on shipping by U-boats, indicating some of the factors governing the safety of ships against U-boat attacks, was made during

this period and had considerable influence on Allied measures for the protection of shipping. This study indicated that the safety of independent ships

depended very much on the speed of the ship, with the 12-to-14 knot region being critical. A 12-knot ship had about three times the probability of being

sunk as a 14-knot ship making the same trip. The explanation of this appears to be that the U-boat cannot, in general, follow a ship of 14 knots or above

for any length of time and if it is not in a suitable position to make a submerged attack immediately, the ship will escape. The U-boat can follow slower

ships on the surface, at a suitable distance, working round to a position from which it can attack on the surface at night.

Speed was a significant factor in the safety of convoyed shipping only when air escort was present. This study showed that the 9-knot convoys were

considerably safer than the 7-knot convoys when air cover was available. When there was no air escort, the U-boat could proceed towards the convoy at

high surface speeds and the extra 2 knots did little to prevent the U-boat from overhauling it. Another striking result which emerged from this analysis

was that the number of ships sunk was roughly independent of the size of the convoy as long as the number of escorts was the same. This meant that large

convoys would lose, on the average, a smaller percentage of ships to U-boat attack and they would also be more economical in the use of escorts.

The average size of the North Atlantic trade convoys increased gradually during this period, rising from about 46 in March 1943 to about 57 in March

1944. In April 1944 certain changes were made in the North Atlantic convoy schedules in order to allow several escort groups to be withdrawn from convoy

duty for use in the invasion. The HX and ON convoy speeds were changed from 10 knots to 8, 9, and 10 knots in rotation, with the suffix S, N, and F

designating these respective speeds, while the slow SC and ONS convoys were abolished. The average sailing interval between convoys stayed at 7½ days

so that only four convoys sailed each way monthly, instead of six. This produced a substantial increase in the average size of these convoys. The average

size of these convoys was 98 in May 1944 and HXM 292, consisting of 135 ships and six escorts, was the largest convoy of the war to that date.

The danger from U-boat attack in the Western Atlantic was so low during most of this period that it was possible to allow some shipping from the U. S.

coastal convoys to sail independently whenever a lull in U-boat activity occurred. The program was kept flexible in order to maintain a balance between

the increased safety of convoyed shipping and the loss of time due to ships waiting in ports for convoys and sailing at slower convoy speeds. Fast merchant

vessels (generally 11 knots and over), with the exception of those carrying high priority cargo, were able to sail independently along the coast during much

of this period. Whenever the danger of a U-boat attack appeared imminent, independent shipping was ordered into port to await the next convoy. In some cases,

where safety permitted, entire convoys were dispersed and the ships proceeded alone to their destination.

The battle between U-boats and aircraft reached its climax at the beginning of this period, in July 1943. The U-boats, equipped with improved

antiaircraft armament in the form of the quadruple 20mm gun, were traveling on the surface during the daytime and were fighting back against aircraft.

They also traveled through the Bay of Biscay in groups for mutual protection.

As a result of their disastrous experience in July 1943 when 34 U-boats were sunk in the Atlantic by aircraft, the U-boats were forced to abandon

these aggressive tactics. The enemy realized that the U-boats were beaten and decided upon more cautious tactics that favored self-preservation of the

U-boat fleet until new technical equipment and modified U-boats could turn the tide. These new

--54--

tactics involved complete submergence of the U-boats (luring the daytime. The fact that aircraft had swept the U-boats from the surface during

the daylight hours constituted a real triumph for the Allies, as U-boats, robbed of their aggressiveness and mobility, lost a great deal of their

effectiveness.

The new tactics first became apparent in August 1943 in the critical Bay of Biscay transit area. The U-boats reverted to surfacing at night for

the minimum time necessary for charging batteries. In addition, they made the transit hugging the coast of Spain, where it was rather difficult for

the LeighLight Wellingtons to patrol because of their limited range.

These changes had a profound effect on the Bay of Biscay campaign, and the productivity of Allied flying was greatly reduced. About 7000 hours

were flown monthly in the Bay during the 5-month period from August 1943 through December 1943. These flying hours yielded only 12 sightings, six

attacks, and one kill a month. Thus, although the flying effort was greater than during the preceding peak period (February 1943 - July 1943), the

results achieved were only one-fifth as great. Only part of this decrease can be explained by the drop in the number of U-boat transits from 100 a

month in the previous period to only about 45 a month during this period. The average number of sightings per 1000 hours on patrol dropped to only

two and only 25 per cent of the U-boat transits were sighted. The efficiency index (sightings per 1000 flying hours on patrol per 100 U-boat transits)

dropped from nine in the previous period to only four.

The U-boats' policy of maximum submergence during the daytime put great pressure on the development of suitable equipment and tactics to enable the

air offensive to be maintained during the night. Considerable effort was devoted to the development of searchlights and flares that would improve the

low effectiveness of night attacks, and the first attack on a U-boat by a U. S. searchlight-equipped plane was made in December 1943 by a PBM from

Trinidad. In addition, squadrons were trained in night operations from escort carriers.

Coastal Command made a great effort to increase the amount of effective night flying in the Bay of Biscay by increasing the number of long-range

searchlight-equipped planes. Leigh lights were fitted to Liberators as well as to additional squadrons of Wellingtons. The effectiveness of this

increased amount of night flying was counteracted by the U-boats' use of the Naxos GSR, which detected Allied S-band (10-cm) radar. The enemy started

fitting his U-boats with this equipment in October 1943. The net effect of these changes was a small increase in the number of sightings in the Bay of

Biscay. About 20 sightings and 15 attacks were made monthly in the Bay during the first five months of 1944. However, the effectiveness of Allied flying

in the previous peak period was not even approached.

U. S. Navy planes participated in the Bay of Biscay offensive during this period under the operational control of Coastal Command. When the U-boat

situation along the East Coast of the United States started easing up in August 1943, the U. S. Army Anti-Submarine Command was withdrawn from antisubmarine

operations. The U. S. Army Air Forces squadrons which had been operating in England were relieved by U. S. Navy Liberators. The U. S. Navy planes in

England constituted Fleet Air Wing 7.

Carrier-based aircraft emerged as one of the most dangerous enemies of the U-boat during this period. The U. S. escort carriers took the offensive

against the U-boat in regions outside the range of shorebased aircraft, especially in possible refueling areas for the U-boats. This offensive was

remarkably successful and rendered most of the Atlantic unsafe for surfaced U-boats.

The U. S. escort carrier [CVE] operating with a screen of about four destroyers or destroyer escorts, composed a task group, assigned to antisubmarine

warfare in the Atlantic. The primary mission of the task group was to protect convoys while the secondary mission was to search out and destroy the

U-boats. These task groups operated with the convoys between the United States and Gibraltar. That the primary mission was accomplished may be seen

from the fact that 2200 ships crossed the Atlantic in the GU and UG convoys from May 1943 through December 1943 and only one ship was sunk by U-boat

action.

A study of attacks made by U. S. CVE-based aircraft during this period provides some evidence that their secondary mission was also fulfilled. About

28 days were spent in U-boat waters on the average cruise and about 50 plane hours were flown per day. While in U-boat waters, one sighting was made for

every 600 flying hours. Sixty of the 68 sightings studied resulted in an attack and about 40 per cent

--55--

of the attacks resulted in the sinking of the U-boat. The high quality of these attacks was due in a large part to the ability of the fast

CVE-based planes to surprise the U-boat and attack it while it was still on the surface. Another factor in the success of these attacks was the

cooperation between the F4F fighter planes, who strafed the U-boat, and the TBF bombers.

The British escort carriers, operating in the very bad weather of the Arctic, played a major role in getting the Russian convoys through. The

North Russian convoys were started again about November 1943 after having stopped running in March 1943. The sinking of the Scharnhorst was the

most publicized part of this battle. The U-boats accomplished much less against these convoys during this period than in the past. During the period

from December 1943 through May 1944, the U-boats sank only five merchant vessels and two destroyers from these convoys while 11 U-boats were sunk.

British escort carriers played a major role, contributing six of the 11 U-boat kills. In one round trip of 16 days, with only eight days of operational

flying, Swordfish planes from HMS Chaser sighted 21 U-boats, attacked 15, and with the aid of surface craft sank three of them.

Rocket projectiles were used very successfully by the British carrier-based aircraft during this period. The first rocket attacks by U. S. planes

were made in January 1944 by aircraft from the USS Block Island. The U-boat was sunk; however, it was difficult to decide whether the sinking was due

to the rockets or to depth charges which were also used in the attack.

The lethality of aircraft attacks during this period was more than twice as high as it had been in the previous period. About 25 per cent of the

aircraft attacks made on the U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean resulted in the destruction of the U-boat while about 40 per cent of the attacks

resulted in at least some damage to it. The effectiveness of aircraft attacks in the first half of 1944 was lower than the peak reached during the last

half of 1943 when some U-boats were still staying on the surface and fighting back. This falling off in effectiveness also reflected the U-boats' tactics

of maximum submergence during the daytime as a much larger proportion of aircraft attacks, during the first half of 1944, were made at night. The

accuracy of night attacks was always much lower than that of day attacks.

| 6.2.3 |

Scientific and Technical |

The decisive defeat suffered by the U-boats during the previous period seemed to have stimulated German scientific and technical progress and a

number of radical changes were made in U-boat weapons and equipment during this period.

One of the changes in U-boat weapons involved the replacement of the quadruple 20-mm antiaircraft gun mount by a new rapid-firing 37-mm antiaircraft

gun. U-boat torpedoes were equipped with FAT gear for use against convoys. This gear caused the torpedo to describe a zigzag course and thereby increased

the probability of a hit. The major change in U-boat weapons was the introduction of the T-5 torpedo, a 21-inch electrically driven acoustic homing torpedo.

The speed of the T-5 torpedo was about 25 knots and its range about 6000 yards. This torpedo homed on the noise of the target's propellers and its homing

radius on a 15-knot escort was usually over 500 yards.

The Allies immediately introduced countermeasures to the acoustic torpedo. The British twin FOXER (towed parallel-bar noisemakers used to decoy the

acoustic torpedo from the ship) was born three months before the first acoustic torpedo attack took place. A complete escort group was fitted with twin

FOXERS 17 days after the first attack. U. S. ships were fitted with FXR gear, which was similar to the British equipment but involved only a single

noisemaker. Ships towing noisemakers or proceeding at speeds greater than 24 knots or less than 7 knots were considered to be relatively safe from

acoustic torpedo attacks. Other ships were instructed to use the step-aside procedure when conducting attacks on U-boats which might fire an acoustic

torpedo. This was a special tactical maneuver, involving a radical change in course when the U-boat is approached, designed to remove the escort vessel

from the most probable danger area from acoustic torpedoes.

The use of these towed noisemakers was unpopular on many ships due to the inconvenience involved in streaming and recovering the gear, to the

reduction in maneuverability, and also to the interference with the sonar equipment. However, the noisemakers were undoubtedly effective against

the acoustic torpedo. About 32 escorts and 19 merchant vessels are estimated to have been hit by acoustic torpedoes during the war. Very few of

these casualties occurred when either the recommended tactical procedure was used, or the towed noisemakers were working

--56--

properly. Although the acoustic torpedo was more likely to score a hit than a normal torpedo, there were many cases of malfunctioning of the

delicate mechanisms involved and those torpedoes that did hit were less likely to sink the ship due to the fact that they usually hit in the stern.

The radar battle continued to play a prominent part in the U-boat war during this period. In the summer of 1943, Admiral Doenitz said, "The methods

in radio location which the Allies have introduced have conquered the U-boat menace." However, the German High Command did introduce some effective

countermeasures in the fields of radio communication and radar detection during this period, mainly because German Intelligence finally became aware

of the nature of Allied equipment.

The major German scientific effort was put into the development of a search receiver that could detect Allied radar transmissions. At the beginning

of this period the enemy still had no idea as to what had caused the huge increase in sightings and attacks on U-boats. The German search receiver had

been improved by the fitting of a drum-shaped aerial (wire-basket) which did not have to be removed when the U-boat dived. A better receiver (Wanz G-1)

had been perfected and was being fitted on U-boats. This served to reduce the amount of radiation from the set itself but did not help the U-boat situation

at all as it could only detect radiation of wavelengths greater than 120 cm. The Germans then introduced the Borkum receiver, a much less sensitive crystal

detector covering the 75- to 300-cm band, which produced no radiation at all.

Serious as were the immediate effects of these errors of judgment for the Germans, they extended far beyond their original limits. They engendered in

the minds of U-boat captains a fear lest they should betray their presence, and with this fear a distrust of Admiral Doenitz' technical advisers.

Finally, in September 1943, the U-boat command recognized that 10-cm radar was being used against them. The German Air Force had captured the blind

bombing aid, H2S, which operated on the 10-cm band, in March 1943 and after a period of six months this information finally filtered through to

the German Navy. As the simplest countermeasure, and still under the influence of their fear of radiating, the Germans produced in October 1943 a

crystal detector receiver, the Naxos, for the 8- to 12-cm band. The first models were crude portable units mounted on a stick. They were not pressure-tight

and had to be passed below before diving. The maximum theoretical ranges on Allied radar sets varied from about 5 to 10 miles, but there was a

considerable loss of efficiency under operational conditions.

The introduction of the Naxos search receiver did reduce the number of sightings and attacks on U-boats and the number of disappearing contacts on

Allied radar sets increased. However, many U-boats continued to be surprised successfully, due to the low efficiency of the gear, and it was evident to

the Germans that they still did not have the final solution to the radar problem. The U-boat command took the step of sending to sea a U-boat fully

equipped to investigate every type of Allied radar and carrying one of their best technicians with operational experience. He sailed from St. Nazaire

in U-406 on February 5, 1944, and was captured when the U-boat was sunk by HMS Spey on February 18. A similarly equipped U-boat suffered the same fate

in April 1944. These losses probably set back the German radar countermeasures program considerably.

Since the Allies were well aware of the potential effectiveness of an S-band search receiver, there were frequent false alarms reporting the

introduction of a new GSR before any existed. The intelligence about Naxos, the increase in disappearing radar contacts, and the drop in U-boat

sightings produced immediate Allied reactions. There were a few cases where S-band radar sets were turned off. Steps were taken to develop attenuators,

which caused a slow and steady decrease in transmitted power as the range closed, in order to confuse GSR operators. An interim tactic of a "tilt-beam"

approach to reduce signal intensity as the range closed was proposed but this proved rather difficult to carry out in actual practice. In addition,

increased pressure was put on the development and fitting of X-band radar (3-cm wavelength).

The general conclusion was that S-band radars should not be turned off, due to their much greater search width as compared to visual search and also

to the fact that the Naxos sets were inefficient and sightings and attacks continued to be made on U-boats with GSR. In addition, the very fact that

aircraft were causing the U-boats to submerge, thereby blinding and partially immobilizing them, greatly reduced the effectiveness of the U-boats in

sinking ships.

The Germans produced a number of other developments

--57--

|

FIGURE 5. Attack by U. S. Navy Liberators (VPB-107) between the coast of Brazil and Ascension Island,

November 5, 1943. Note the radar antenna in its fairing on the left side of the conning tower, and just forward of it, an early form of the Naxos

search-receiver antenna. The guns are still pointing at the previous position of the aircraft, while the gun crews seek cover from the 20-mm fire

from the aircraft's turrets. |

in the radar field. A radar decoy spar, designed to give false radar echoes was introduced, but proved ineffective. Some work was done on radar

camouflage, with the object of developing rubber coatings for the U-boats that would deflect or absorb radar echoes. Earlier, there had been some

attempt to use these rubber coatings against sonar, too. However, the difficulties of producing rubber coatings that would work under operational

conditions at sea were very great. The Germans also continued their experiments with infrared searchlights and receivers and took steps to prevent

the detection of U-boats by imagined Allied infrared equipment.

During this period, the U-boats finally began to appreciate the danger from Allied shipborne HF/DF as the result of a special Y party going to

sea on a specially equipped U-boat. The U-boat command connected their diminishing success to some extent with their communications and tightened

them up considerably. The lengths of messages were reduced and the frequencies used were changed more often. These shifts, while they made HF/DF

both ashore and afloat more difficult, did not seriously reduce its use or effectiveness. They did make the task of U-boats attacking convoys more

difficult.

The most revolutionary technical development of this period was the fitting of Schnorchel to U-boats. The Schnorchel (or snout) is an extensible

mast, consisting of an air induction trunk and a diesel exhaust line which are enclosed in a metal fairing. The cross

--58--

|

FIGURE 5. Close-up of U-1229, a 740-ton U-boat under attack by aircraft from USS Bogue, which later

sank it. Note the extended Schnorchel just forward of the conning tower. |

section of this fairing is streamlined with the maximum dimension about 20 inches. The mast is about 26 feet in length and when raised is a

few inches lower than the top of the extended periscope. The Schnorchel enables a U-boat to travel on its diesel engines at periscope depth at

speeds of about 6 knots and also to charge batteries without surfacing. In essence, it was a defensive weapon, designed to reduce the amount of

time the U-boat had to spend on the surface and consequently to reduce the danger from air attack.

The idea of an extensible air intake, which would enable a U-boat to charge its batteries while submerged, had been current in the German Navy

in pre-war years but was first brought forcibly to its attention by the capture, in 1940, of two Dutch submarines fitted with such equipment. No

steps were taken to follow up this idea while things were going well for the U-boats, and it was not developed until the end of 1943, after aircraft

had gained the upper hand over U-boats. The first U-boats were not fitted with Schnorchel until February 1944, and it was not until June 1944, the

start of the next phase of the U-boat war, that its effect on U-boat operations became significant.

The U. S. Navy introduced during this period a number of new devices designed to improve the sonar performance of its ships. The Bearing Deviation

Indicator [BDI] was one of the most helpful of these sonar aids. BDI was used with standard echo-ranging

--59--

equipment to let the operator see, for every ping, whether the target producing the echo was to the right or left of the bearing of the projector.

The operator could, therefore, determine the bearing of the target with greater accuracy and rapidity than with standard echo-ranging equipment alone.

Two new types of depth charges came into use on U. S. ships during this period. The Mark 8 depth charge was fitted with a magnetic proximity fuze

which was designed to detonate when within lethal range of the U-boat. The Mark 9 depth charge was steel-cased and shaped so as to have a fast sinking

rate, thereby reducing the blind time and consequently the effect of U-boat maneuvers. Both these new depth charges were designed to increase the lethality

of surface craft attacks on U-boats.

The British also improved the antisubmarine equipment on their ships during this period, but along different lines than the U. S. Navy. The Squid,

which is designed to throw depth charges ahead of the ship and is automatically controlled and operated, came into service at the beginning of 1944.

It employs a 3-barreled mortar, electrically fired, designed to discharge bombs ahead of the attacking ship. These bombs closely resemble depth charges

in weight and explosive effect but have the following advantages over depth charges:

- They are projected with accuracy to a known point, well ahead, while the attacking ship is still in Asdic contact with the U-boat.

- They have a reliable underwater course.

- They have a much higher sinking speed.

- They incorporate a new type of fuze which is set automatically to the required depth with a high degree of accuracy.

The depth is set on the fuzes electrically from the new Type 147B Asdic depth predictor. The mortars are fired automatically from the Asdic

range recorder. The three charges are thrown to the points of an equilateral triangle. When two mortars are fitted, as in frigates, the pattern

is in two depth layers.

The Type 147B Asdic depth predictor was developed primarily for use with the Squid, so as to obtain a measurement of the depth of the U-boat

just before the projectiles are fired. However, the Type 174B depth predictor, in conjunction with the appropriate range and bearing recorders and

Q attachment, can also be used in Hedgehog and depth-charge attacks. Type 147B uses a fan-shaped beam of high-frequency sound (50 kc) which may be

depressed down to 45° below the horizontal. The beam of sound is broad in the horizontal plane (30° to 40° on either bow) and narrow in

the vertical plane (2° to 3° off axis). Trials have shown that the set is capable of setting the Squid fuzes to within about 20 feet of the

depth of the U-boat, provided it is below 100 feet. At shallower depths it is not possible to get accurate measurements. It is possible to make accurate

attacks on U-boats at depths down to some 800 feet, provided that the Q attachment is fitted.

| 6.2.4 |

Sinkings of U-boats |

The average number of U-boats sunk or probably sunk monthly reached a peak of 21 a month during this period. The record monthly score of the war

was reached in the first month, July 1943, when 46 U-boats were destroyed throughout the world. Of the total of 234 U-boats destroyed during this 11

month period, 199 were German, 28 were Japanese, and 7 were Italian. The 180 U-boat sinkings in the Atlantic were rather widely distributed with the

leading areas being the Northwest Atlantic Area with 34 kills, the Northeast Atlantic Area with 29 kills, and the Biscay Channel Area with 28 kills.

Aircraft continued to be the leading U-boat killers during this period accounting for 122 alone (52 per cent of the world-wide total) and another

22 (9 per cent of total) with the cooperation of surface craft. Carrier-based aircraft accounted for 40 of the 144 kills in which aircraft participated.

Ships accounted for 79 U-boats (34 per cent of total), and Allied submarines accounted for the other 11 U-boats (5 per cent of total).

The quality of surface craft attacks continued to improve steadily through this period as the crews became more experienced and improved weapons and

equipment became available. About 30 per cent of the surface craft attacks made on U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean during this period resulted

in at least some damage to the U-boat while 20 per cent of the attacks resulted in the sinking of the U-boat. The lethality of these attacks was twice as

high as it had been during the previous period. A study of British assessed attacks during this period indicated that about three patterns were dropped

in the average attack on a U-boat. The probability of sinking a U-boat was about 6 per cent for the average depth-charge pattern and about 11 per cent

for the average Hedgehog pattern.

--60--

| 6.3.1 |

From the U-boat's Point of View |

To interpret the results of the U-boat war during this period correctly, it is important to realize that the German High Command appreciated, at

the beginning of this period, that the U-boats had been decisively defeated in the crucial battle against the North Atlantic convoys. The enemy also

realized that the old type of U-boat would have to be modified radically before it could again be a serious menace to the Allied supply lines across

the Atlantic.

The solution reached by the German High Command was the development of an entirely new type of U-boat, more immune from radio location, with much

greater submerged speed, and an entirely new and quicker method of production. The first sketch of what was to be the new prefabricated Type XXI U-boat

was made in July 1943. By December 1943 all designs were finished, including full-scale wooden mockups. In February 1944 it was decided to stop the

construction of the old-type U-boats, except that those that had already been laid down were to be completed, and to concentrate on the production of

the new prefabricated U-boats.

The general strategy of the enemy was to keep the U-boat fleet in being until the new U-boats would be ready, when they could return to the offensive

again. In line with this policy, the Schnorchel was valuable as an interim measure, to reduce the danger from air attack and to enable the U-boats to

operate in inshore waters in the event of invasion. The main aim of the U-boats during this period was self-preservation, although they would attempt

in the meantime to sink as much Allied shipping as they could without suffering excessive losses. In addition, keeping the U-boats at sea served to tie

up large Allied forces in the protection of shipping, thereby keeping them from being used against Germany in other ways.

During the last half of 1943, the U-boats made several attempts at conducting offensive operations but each time they were beaten back with heavy

losses. Thereafter, the U-boats seemed to realize that, if they were to accomplish their primary mission of self-preservation, they could not undertake

any large-scale offensives against shipping. The number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic dropped steadily, reaching a minimum of about 40 in May 1944.

The main functions of these U-boats, during the first five months of 1944, were probably reconnaissance, weather reporting, forcing the Allies to convoy

shipping, and waiting for the invasion. They made no attempt to sink a large amount of Allied shipping. This is clearly reflected in the results achieved

by the U-boats during this period.

World-wide shipping losses to U-boats reached a new low as only about 17 ships of 101,000 gross tons were sunk monthly by U-boats. This was only

about one-fourth the amount sunk monthly by U-boats during the previous period. Only about 45 per cent of these sinkings took place in the Atlantic,

as about 40 per cent occurred in the Indian Ocean and another 15 per cent in the Mediterranean. The worldwide number of U-boats sunk monthly reached

a peak of about 21 a month during this period. The world-wide exchange rate reached a new low of only 4/5 of a ship (4800 gross tons) sunk by the

average U-boat before it itself was sunk.

U-boat activity in the Mediterranean was slightly lower than in the preceding period. Sicily was invaded in July 1943 and the Mediterranean was

considered open for Allied shipping, although almost all of it was forced to travel in convoy. Only 36 merchant vessels were sunk by U-boats during

this period at a price of 23 U-boats sunk.

Shipping losses to German and Japanese U-boats in the Indian Ocean were at a slightly higher level than previously as 71 ships were sunk during

this 11 month period. However, this was the first period in which there was some evidence of countermeasures against the U-boats in the sinking of

seven U-boats. This was one of the few areas where the exchange rate was still favorable for U-boat operations as 10 ships were sunk by U-boats for

each U-boat sunk.

Japanese U-boats were strictly on the defensive in the Pacific and spent most of their time in supplying isolated outposts. Despite the fact that

the bulk of the shipping in the Pacific sailed independently, only one merchant vessel was sunk by U-boats during this 11-month period, while Allied

forces, mostly surface craft and submarines, sank 24 Japanese U-boats in the Pacific.3

The average number of U-boats at sea in the Atlantic during this period was only 61, about 40 percent less than the average number at sea during

the previous period. These U-boats sank only eight ships of 44,000 gross tons per month in widely scattered areas of the Atlantic. The average U-boat

in the Atlantic

--61--

reached a new low in offensive power as it was able to sink only 1/8 of a ship (700 gross tons) per month at sea.

Despite the meager results achieved by the average U-boat and the smaller number of U-boats at sea, the number of U-boats sunk in the Atlantic

continued to increase as 16 were sunk monthly during this period. The average life of a U-boat at sea in the Atlantic during this period was, therefore,

only about 4 months, half the average life of a U-boat at sea in the previous period. This meant that the average U-boat at sea in the Atlantic was

able to sink only i2 of a ship (2800 gross tons) before it itself was sunk. The magnitude of the disaster which the U-boats suffered during this period

may be roughly measured by the fact that the exchange rate (ships sunk per U-boat sunk) was about nine times as high in the previous period, the battle

against the North Atlantic convoys, and about 38 times as high in the peak period, the first 9 months of 1942.

These figures reflected the growing strength and efficiency of Allied surface and air craft and the widening gap between Allied weapons and equipment

and that of the U-boats. They also confirmed the German High Command's appreciation, at the beginning of this period, that the old-type U-boat could not

compete any longer with Allied antisubmarine forces. The only consolation the enemy could have, at the end of this period, was that the U-boat losses

would probably have been much larger than they actually were if the U-boats had actually continued their large-scale offensive against Allied shipping.

This is indicated by a comparison of the 16 U-boats sunk monthly in the Atlantic with the 37 U-boats sunk in July 1943 and the 25 U-boats sunk in

October 1943, the months in which the U-boats attempted offensive operations.

By operating their U-boats as they did, the Germans were able to maintain their large U-boat fleet for the invasion. About 250 new German U-boats

were constructed during this period while only about 200 German U-boats were sunk so that the Germans had over 400 U-boats at the end of this period.

| 6.3.2 |

From the Allies' Point of View |

The Allied and neutral nations lost about 184,000 gross tons of shipping monthly from all causes during this period, only about a third

of the monthly shipping losses during the preceding period, while the construction of new merchant shipping ran at about 1,160,000 gross

tons monthly, slightly higher than during the preceding period. Consequently, there was a net gain of about 976,000 gross tons a month in

the amount of shipping available.

The shipping available to the Allies had increased by almost 11,000,000 gross tons during this period to a total of about 7500 ships of

47,500,000 gross tons. About 10,500,000 gross tons of this total consisted of tankers. October 1943 was the first month in which the total

shipping available was larger than the 40,000,000 gross tons of shipping available at the start of the war, in September 1939. It took over

four years to replace the heavy shipping losses caused mostly by U-boat action in the early years of the war.

By the end of this period, the shipping crisis had definitely passed and the Allies had sufficient shipping available to undertake the

invasion. In fact, construction of new merchant shipping had started tapering off in 1944 after reaching a peak of 1,500,000 gross tons in

December 1943. Part of this tapering off was due to the conversion of shipyards to the construction of the faster Victory ships which took

about twice as long to build as the slower Liberty ships.

Of the 184,000 gross tons of shipping lost monthly from all causes, 147,000 gross tons were lost as a result of enemy action. U-boats

accounted for 101,000 gross tons a month, about 69 per cent of the total lost as a result of enemy action. Monthly shipping losses due to

enemy aircraft were higher than in the preceding period, amounting to 34,000 gross tons a month, about 23 per cent of the total due to enemy

action. Shipping losses from enemy surface craft, mines, and other enemy action were even lower than in the preceding period, totaling only

22,000 gross tons a month, or 8 per cent of the total.

The major task of the Allies during this period had been accomplished. Sufficient supplies and men had been landed in England during this

period to enable the Allies to undertake the invasion of Europe in June 1941. Although the U-boats were no longer the serious menace the),

had been in the past, the large U-boat fleet based on both flanks of the English Channel constituted a potential threat to the success of

the invasion. The immediate problem facing the Allies, at the end of this period, was to prevent the U-boats from attacking the large

concentration of shipping that would be carrying troops and military equipment across the Channel during the invasion. From a long-term

point of view, it was necessary to

--62--

maintain the numerical and technical superiority of Allied antisubmarine forces over the U-boats. Allied antisubmarine forces faced the

problem of preventing the U-boats from ever cutting the large and continuous flow of supplies that would be required by Allied fighting

forces in Europe.

--63--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (5) *

Next Chapter (7)

Footnotes

Transcribed and formatted for HTML by Rick Pitz for the HyperWar Foundation