Chapter 8

SUMMARY OF ANTISUBMARINE WARFARE

WORLD WAR II

The opening hours of the war saw the U-boats already in position astride the approaches to the United Kingdom. Their aim throughout the war was to

sever the flow of merchant shipping to and from Great Britain, and in the attempt the battle was carried halfway around the world. The U-boats held the

initiative from the beginning until their disastrous defeat in the summer of 1943. Thereafter all their efforts were futile, and U-boat warfare, old

style, was at an impasse when the war ended. What the enemy might have accomplished with the new U-boats having high submerged speed is conjectural, but

there can be no doubt that they would have been a serious menace.

The actual achievements of the German, Italian, and Japanese U-boats during the war resulted in the Allies' loss of 2753 ships4 of 14,557,000 gross tons. The enemy also suffered considerable losses at sea. It is estimated that

733 German, 79 Italian, and 99 Japanese U-boats were sunk. A total of about 1500 U-boats were built by the enemy, however, to achieve these results.

There were, therefore, about three Allied merchant vessels sunk by U-boats for each U-boat sunk, about two merchant vessels sunk for each U-boat built.

In addition, the Allies were forced to maintain a large and costly antisubmarine effort which diverted their attention from other phases of the war. In

these terms the U-boat war was a profitable one for the enemy, even though the U-boats were ultimately defeated. If German U-boat operations only were

considered, this conclusion would be greatly strengthened. During the period prior to June 1943 they were, of course, unquestionably successful, whereas

subsequent operations were an equally complete success for the Allies.

The beginning of the war saw an immediate campaign of unrestricted U-boat warfare. The British had anticipated such a development and put a previously

planned convoy system in operation within a few days. The scale of effort was small, however, as there were only a small number of U-boats at sea, and the

antisubmarine craft available to the Allies could give only very weak escort to the convoys.

The U-boats concentrated their forces in the vicinity of Britain, making their attacks in daylight from periscope depth. Their tactics were highly

aggressive, and each U-boat scored heavily against Allied shipping. As a result they exposed themselves to counterattack by British surface craft, whose

Asdic-directed attacks proved to be much more effective than the Germans were expecting. Surprised and confused by the success of British escorts, the U-boats

devoted most of their attention to independent ships and those in convoy were relatively safe, even though weakly escorted.

In June of 1940 France fell to the German Army. The resulting worsening of the British strategical situation had a direct effect on the U-boat war. In the

first place the threat of a seaborne invasion of England confined large numbers of British air and surface craft to the east coast anti-invasion patrols and

diverted them from antisubmarine duties. In addition, the acquisition of bases on the Bay of Biscay cut down on the transit time of the U-boats and allowed

them to extend their operations farther into the Atlantic.

As a result of the effective counterattacks suffered by submerged U-boats, the Germans introduced a radical change of tactics. They began to attack on the

surface at night, a procedure that was characteristic of them during most of the war. They capitalized on the weakness of British escorts and made many of

--80--

the attacks on convoys, usually trailing the convoy until darkness, then coming in trimmed down on the surface for the attack, and retiring on the

surface at high speed.

This method was highly successful, and bold individual attacks rolled up large tonnages to the U-boats' credit. The risks were proportionately high,

however. By such tactics the outstanding U-boat aces, Prien, Kretschmer, and Schepke, each amassed totals of over 200,000 gross tons, but all three were

eventually sunk in March 1941.

One of the most significant countermeasures to these surfaced attacks was the introduction of radar; a makeshift aircraft set was first fitted to escorts

in November 1940. Its effectiveness was not great, however, during this early period. Various improvements in the convoy system were made by the British,

including the formation of escort groups, Admiralty control of routing, and a wide dispersion of convoy routes. As a result, U-boats had greater difficulty

in attacking convoys.

Early in 1941 the results of Germany's U-boat construction program began to be felt. In 1939 the Germans had only a small U-boat fleet, since their

hopes were for a short war. When the possibility of a long struggle with Britain became apparent, building of U-boats was given high priority. They were

commissioned at a rate of about 20 a month starting in 1941. There was a corresponding increase in U-boat personnel which, of course, resulted in a

widespread lowering in their general experience and capability. This was accentuated by the loss of some of the best trained crews.

In the summer of 1941, therefore, the bold tactics of individual night surfaced attacks on convoys were modified. The policy of wolf-pack attacks

came into use in an attempt to overwhelm the convoy escorts. The procedure was for the U-boat first contacting a convoy to withhold attack, trailing

the convoy and homing other U-boats to the scene so that a number could join in the attack, thus capitalizing to the full on the opportunity and reducing

the danger to the attacking U-boats. Complementary to this policy was a general movement of U-boats to the west and south in an effort to find independent

ships. This movement also gave freedom from the growing air cover in the vicinity of Britain.

As a result of these changes, the British were forced to adopt complete end-to-end escort of transatlantic convoys. They were aided in this effort

both by the German attack on Russia in June 1941 which ended the threat of' invasion of England and released craft for antisubmarine operations, and by

the entry of the U. S. Navy in convoy operations in September. Despite the great increase in number of U-boats at sea, Allied losses of merchant vessels

did not increase.

Another change introduced by the British during 1941 was to have a Profound effect on the antisubmarine war, in this case the contribution made by

aircraft. Air patrol had been effective in harassing the U-boats from the beginning, but very few successful attacks were made for lack Of suitable

weapons. The need for a depth bomb exploding at shallow depths was finally realized, and a 25-foot depth setting came into use. With this minor change

aircraft eventually became the equal of surface craft as killers of U-boats.

With the U. S. entry in the war at the end of 1941 the scope of U-boat operations expanded rapidly. The Germans had a large and rapidly growing

U-boat fleet, so that they were able to launch a full-scale offensive against the weakly protected shipping in U. S. coastal waters. They were at first

able to choose and sink their victims virtually unimpeded, and Allied losses reached catastrophic size, 140 ships of 698,000 gross tons in June 1942,

for example. Defenses were organized, however, which forced an eventual withdrawal of the U-boats. With the introduction of convoying in Eastern Sea

Frontier in May, losses in that area were reduced, while those in Gulf Sea Frontier soared. U-boat successes there were short-lived, though the Caribbean

remained a soft spot throughout the summer of 1942. Nevertheless the continued extension of convoying and air patrol drove the U-boats out of the coastal

areas by fall, and they then returned to the North Atlantic.

During this period U-boat activity in the Eastern Atlantic was at a standstill. Consequently British forces were free to begin a counteroffensive

against U-boats in transit from their bases to the operating areas in the Western Atlantic. Coastal Command aircraft patrolling the Bay of Biscay with

radar and searchlights inflicted considerable damage on the U-boats during the summer, until countered by German search-receiver development.

As a direct effort to make up the heavy shipping losses, the Allies started an intensive building program during 1942. Despite all their efforts,

however, U-boats sank ships faster than they were built until about the end of the year.

--81--

In October it was evident that the U-boats were returning to the North Atlantic in force. Attacks on transatlantic convoys were their objective,

and they operated in the mid-ocean gap which could not be reached by land-based air patrol. This gave them freedom to operate on the surface and gather

very large wolf packs - often ten or more and occasionally as many as 30 to 40. A concerted attack of this sort often led to breaks in the escort formation

and disorganization of the defense.

Nevertheless the vast convoys for the North African invasion made their way from Britain without serious losses because of the complete air coverage

provided for them. Routine trade convoys were less fortunate as the tonnage lost topped 700,000 in November. Against a U-boat fleet which was able to

maintain about 100 U-boats at sea, even the more efficient escorts which were fitted with S-band radar were inadequate. Heavy losses continued during

the winter, mostly in the North Atlantic, but also in other widespread areas where diversionary U-boats were operating.

In the spring of 1943 the convoy defenses were bolstered by a limited amount of aircraft patrol in the mid-ocean gap, which proved to be extraordinarily

effective. A small number of VLR aircraft became available in March, and the USS Bogue [CVE] also sailed in support of the convoys. Considerable numbers

of U-boats were sunk, but they continued to attack in force until early May when they were driven off from ONS 5 in the decisive convoy battle of the war.

After May 17 no ships were sunk in the North Atlantic for some time.

While aircraft were thus distinguishing themselves in the defense of convoys, the Coastal Command offensive against transit U-boats was also bearing

fruit. S-band radar was introduced early in 1943, and the number of sightings and attacks soared. During May, 37 U-boats were sunk in the Atlantic, 11

of them in the Bay of Biscay. The success of these operations continued until the end of the summer.

By July the U-boats had dispersed to try to find a soft spot in Allied defenses. They failed completely, and found themselves attacked even in mid-ocean

by CVE-based aircraft. In Atlantic waters a total of 34 U-boats were sunk, mostly by aircraft. The result of such disastrous losses was a complete defeat

of the U-boats, in which they gave up aggressive surfaced operations and submerged during daylight hours to avoid aircraft. Ultra-conservative tactics were

employed in crossing the Bay of Biscay.

Having thus lost their mobility, the U-boats accomplished nothing until September and October when they attempted to make a come-back against the North

Atlantic convoys by employing acoustic homing torpedoes against the escorts. They were beaten off with heavy losses-22 U-boats sunk during October in

operations against convoys in order to sink three merchant vessels and one escort. An attempt to attack the convoys between the United Kingdom and Gibraltar

was then made, but it was also frustrated and the U-boats forced into a completely defensive position.

For the rest of the winter they adopted a policy of maximum submergence, designed to give them safety from Allied attack. Virtually no ships were

sunk. The number of U-boats at sea declined markedly, and every effort was made to develop an effective search receiver for S-band radar to give them

immunity from detection by the Allies.

It was not until the invasion of Normandy in June 1944 that the U-boats showed any signs of aggressive action. Their effort to attack shipping in

the English Channel was short-lived, however, as heavy air and surface patrols prevented them from achieving any success. They soon abandoned the

surface in favor of Schnorchel operation which gave them virtual immunity from detection by aircraft. By lying on the bottom the were able to utilize

the poor sound conditions and frequent wrecks to gain considerable safety from Asdic. Operating in this way limited successes against shipping in

British coastal waters were achieved during the summer, while sinkings of U-boats became less and less frequent.

In August and September the U-boats withdrew from the Biscay bases to Norway, and then settled down to a small-scale offensive around Britain. They

met with some success at first, but by the spring of 1945 Allied surface craft had learned to deal with them under those conditions, and the Allied

victories on land deprived them of bases and shore facilities. Their only chance for regaining the upper hand was the new high submerged speed U-boat,

Type XXI, but due to production difficulties and the general German collapse none of them made an operational patrol against the Allies.

With the German surrender in May 1945, U-boat warfare was to all intents and purposes ended. Japanese U-boats caused the Allies no serious concern

during the remainder of World War II.

--82--

TABLE 1. Average Monthly Shipping Losses and Construction of Allied and Neutral Nations.

(By period and cause of loss and in thousands of gross tons.)

| Cause |

Period I

Sept 39 -

June 40 |

Period II

July 40 -

Mar 41 |

Period III

Apr 41 -

Dec 41 |

Period IV

Jan 42 -

Sept 42 |

Period V

Oct 42 -

June 43 |

Period VI

July 43 -

May 44 |

Period VII

Jun 44 -

Apr 45 |

World

War II

Sept 39 -

Apr 45 |

| Sunk by U-boats |

106 |

224 |

175 |

508 |

394 |

105 |

57 |

214 |

| Sunk by aircraft |

29 |

61 |

76 |

70 |

21 |

35 |

8 |

41 |

| Sunk by ships |

14 |

87 |

17 |

40 |

7 |

4 |

2 |

23 |

| Sunk by mines |

58 |

27 |

20 |

11 |

9 |

5 |

15 |

20 |

| Sunk by other enemy action |

16 |

5 |

34 |

26 |

5 |

2 |

3 |

12 |

| Total sunk by enemy action |

223 |

404 |

322 |

655 |

436 |

151 |

85 |

310 |

| Sunk by marine casualty |

58 |

52 |

40 |

49 |

55 |

32 |

39 |

46 |

| Total losses - all causes |

281 |

456 |

362 |

704 |

491 |

183 |

124 |

356 |

| New construction |

57 |

114 |

175 |

515 |

1026 |

1160 |

850 |

580 |

| Net monthly (loss) or gain |

(224) |

(342) |

(187) |

(189) |

535 |

977 |

726 |

224 |

| |

| Shipping available in million gross tons |

40.0 |

37.8 |

34.7 |

33.0 |

31.3 |

36.1 |

46.9 |

55.0 |

TABLE 2. Average Number of U-boats sunk monthly - World-wide by periods and cause of sinking.

| Cause |

Period I

Sept 39 -

June 40 |

Period II

July 40 -

Mar 41 |

Period III

Apr 41 -

Dec 41 |

Period IV

Jan 42 -

Sept 42 |

Period V

Oct 42 -

June 43 |

Period VI

July 43 -

May 44 |

Period VII

Jun 44 -

Apr 45 |

World

War II

Sept 39 -

Apr 45 |

| Sunk by surface craft |

2.1 |

1.7 |

3.0 |

3.6 |

7.2 |

7.5 |

8.8 |

5.0 |

| Sunk by S/C and A/C |

0.1 |

0.3 |

0.2 |

0.9 |

1.2 |

2.1 |

1.4 |

0.9 |

| Sunk by aircraft |

0.3 |

0.2 |

.04 |

2.2 |

9.3 |

11.3 |

10.0 |

5.1 |

| Sunk by submarine |

0.2 |

0.3 |

.04 |

1.3 |

1.4 |

1.3 |

1.5 |

1.0 |

| Sunk by other or unknown causes |

0.5 |

0.6 |

0.7 |

0.4 |

0.8 |

0.8 |

2.6 |

1.0 |

| Total sunk |

3.2 |

3.1 |

4.7 |

8.4 |

19.9 |

23.0 |

24.4 |

13.0 |

TABLE 3. Approximate German U-boat position.

(Ocean-going U-boats only - 500 tons or more.)

| Period |

At start of period |

Constructed |

Sunk |

At end of period |

|

|

30 |

15 |

23 |

22 |

|

|

22 |

45 |

13 |

54 |

|

|

54 |

174 |

28 |

200 |

|

|

200 |

200 |

50 |

350 |

|

|

350 |

178 |

142 |

385 |

|

|

385 |

250 |

215 |

400 |

|

|

400 |

180 |

234 |

350 |

--83--

|

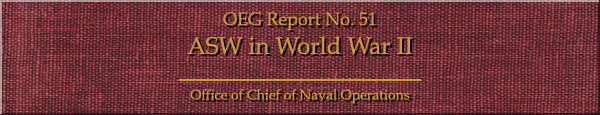

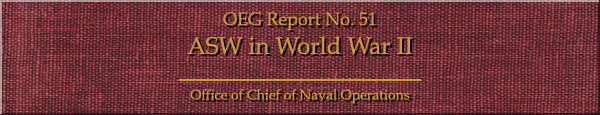

FIGURE 1. U-boat and antisubmarine operations for the seven periods of World War II. |

--84--

The outstanding statistical facts of the antisubmarine war are summarized in the following tables and charts:

- Figure 1 - presents figures measuring the magnitude and effectiveness of U-boat and antisubmarine operations for

the seven periods of World War II. The "remarks" attached explain the outstanding characteristics of each period.

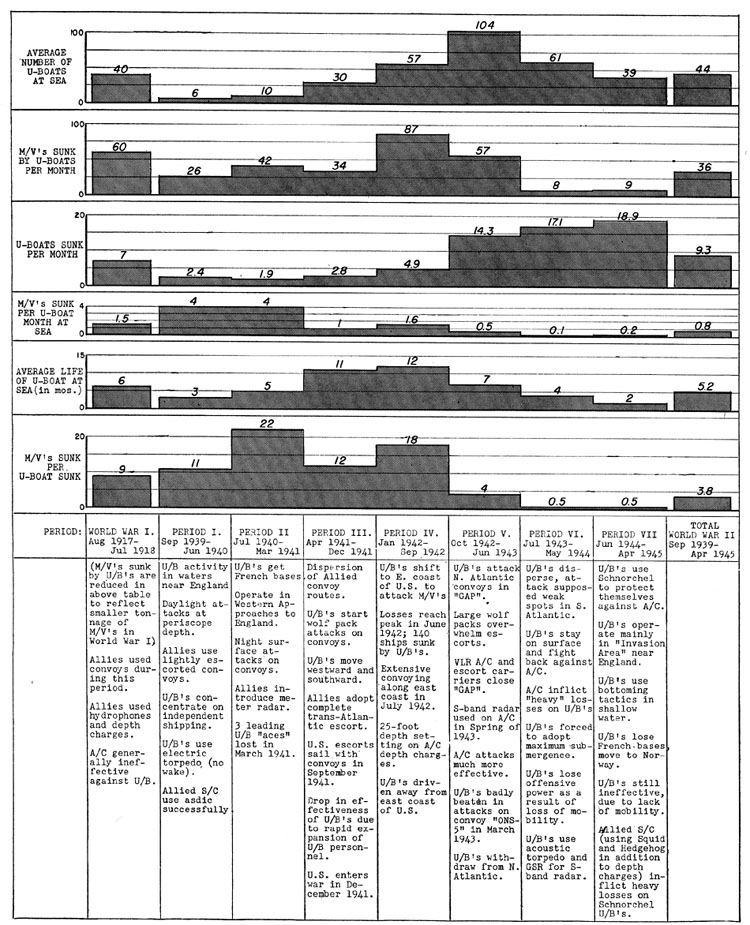

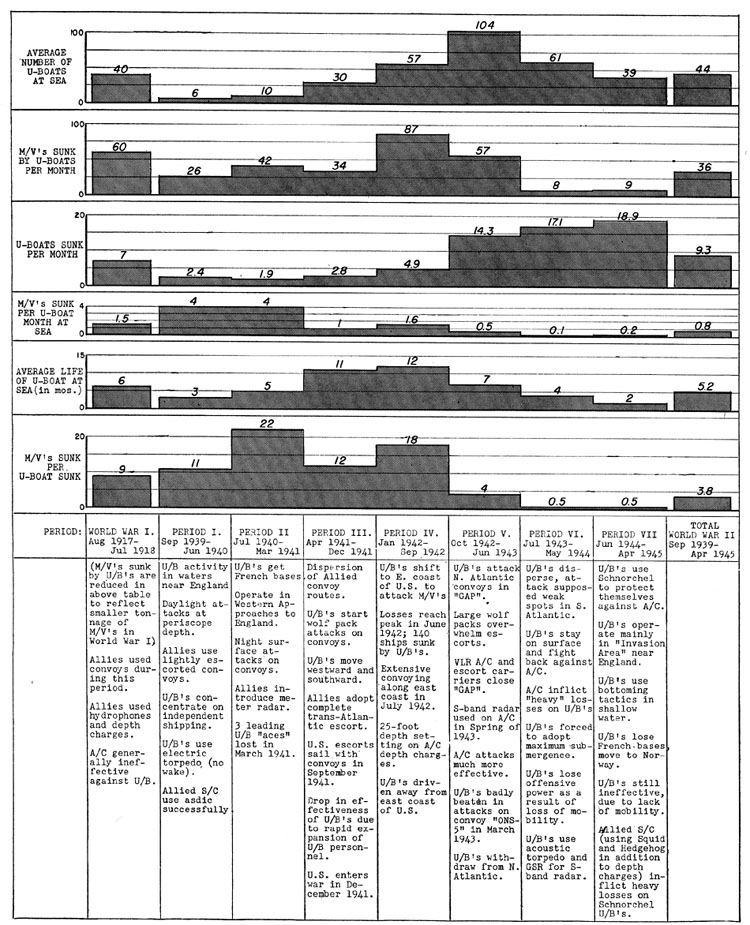

- Table 1 - presents Allied shipping losses due to various causes and gains through construction for each period.

- Figure 2- summarizes the information of Table 1 in graphical form.

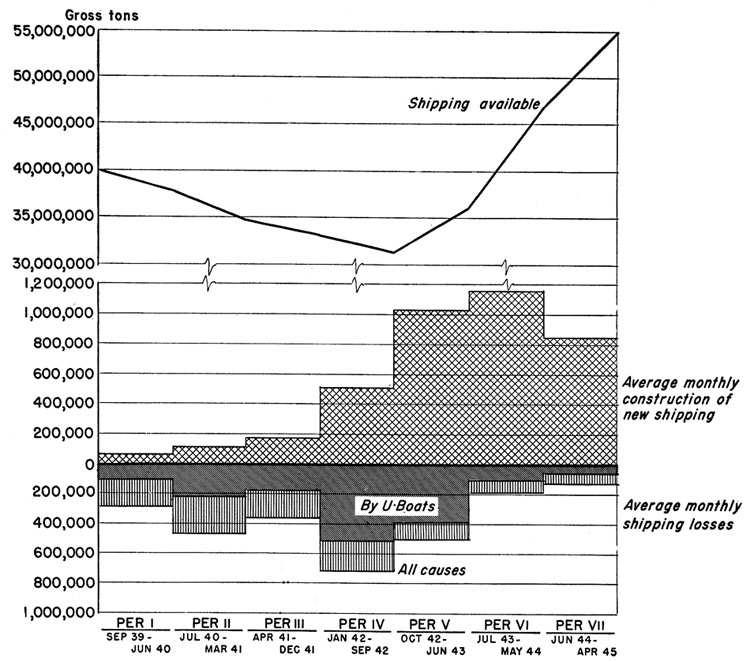

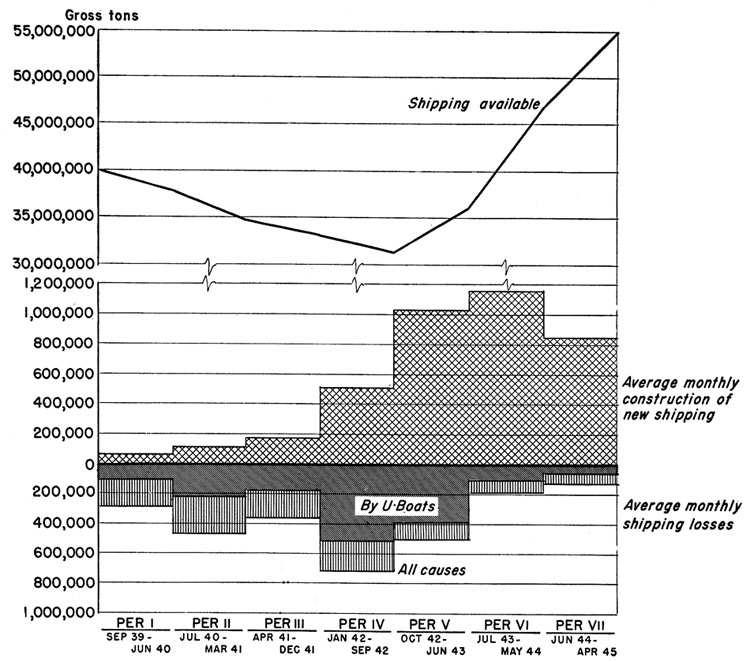

- Table 2 - presents the average number of U-boats sunk monthly by cause for each period.

- Figure 3 - summarizes the information of Table 2 in graphical form.

- Table 3 - presents German U-boat losses gains through construction for each period.

- Table 4 - presents total shipping losses and boat sinkings for each period.

- Table 5 - gives the effectiveness of Allied attacks by aircraft and surface craft on U-boats in the Atlantic and Mediterranean for each period.

|

FIGURE 2. Status of Allied merchant fleet during World War II. |

--85--

|

FIGURE 3. Monthly U-boat sinkings by period and cause of sinking. |

TABLE 4. Shipping sunk by U-boat and U-boats sunk, by period (World-wide).

| Period |

Ships sunk by U-boat |

U-boats sunk |

| Number |

1000 gross tons |

German |

Italian |

Japanese |

Total |

|

|

256 |

1,058 |

23 |

9 |

--- |

32 |

|

|

379 |

2,020 |

13 |

15 |

--- |

28 |

|

|

325 |

1,580 |

28 |

14 |

--- |

42 |

|

|

878 |

4,575 |

50 |

15 |

11 |

76 |

|

|

603 |

3,546 |

142 |

16 |

18 |

180* |

|

|

192 |

1,150 |

215 |

10 |

27 |

252 |

|

|

117 |

618 |

234 |

--- |

35 |

269 |

|

|

3 |

10 |

28 |

--- |

8 |

36 |

|

|

2,753 |

14,557 |

733 |

79 |

99 |

915* |

* Includes 4 Vichy French U-boats.

--86--

TABLE 5. Quality of Allied attacks on U-boats.

(By period - in Atlantic and Mediterranean.)

| Period |

Aircraft

Percent resulting in at least |

Surface Craft

Percent resulting in at least |

| Some damage |

Sinking of U-boat |

Some damage |

Sinking of U-boat |

|

|

10 |

1 |

Satisfactory data are not available for this early period. |

|

|

10 |

2½ |

|

|

25 |

2½ |

|

|

20 |

3 |

15 |

5 |

|

|

25 |

10 |

25 |

10 |

|

|

40 |

25 |

30 |

20 |

|

|

35 |

18 |

35 |

30 |

--87--

*** This Page Intentionally Left Blank ***

--88--

Table of Contents

Previous Chapter (7) *

Next Section (Part II)

Footnotes

Transcribed and formatted for HTML by Rick Pitz for the HyperWar Foundation