Among all Canadian lighthouses the "flying buttress" towers are perhaps the most striking. There were originally nine of these towers, all built from a set of plans drawn by William P. Anderson, Chief Engineer and Superintendent of Lighthouses for the Department of Marine and Fisheries, and all built in a few years around 1910. Six of the nine survive. They are:

- Belle Isle Northeast, Newfoundland

- Escarpement Bagot (Bagot Bluff), Île d'Anticosti, Québec

- Pointe-au-Père, St. Lawrence River, Québec

- Caribou Island, Lake Superior, Ontario

- Michipicoten Island, Lake Superior, Ontario

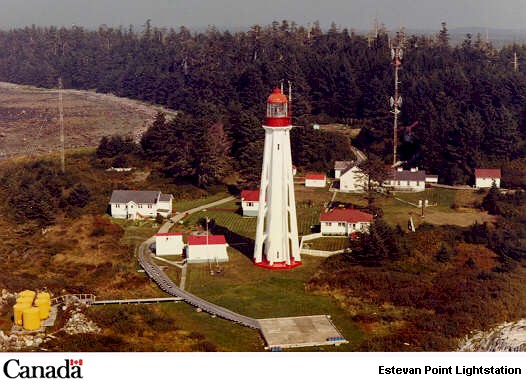

- Estevan Point, Vancouver Island, British Columbia

Three additional examples were demolished during the 1960s. They are:

- Cape Norman, Newfoundland

- Cape Bauld, Newfoundland

- Cape Anguille, Newfoundland

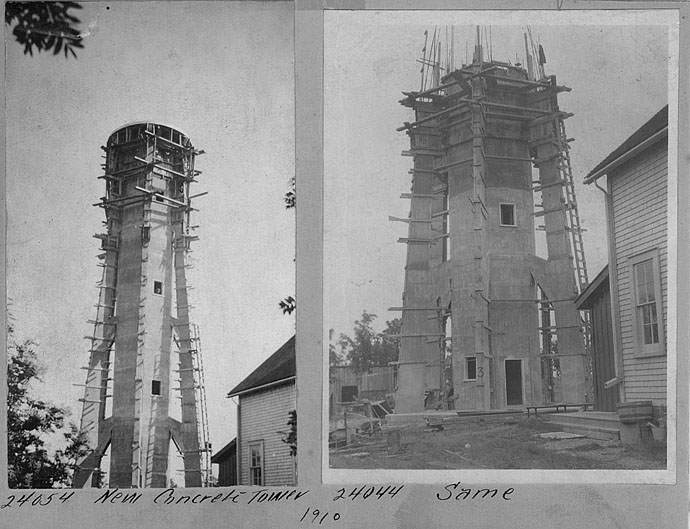

The photo at right is of the Caribou Island Light as it appeared a few years ago before the last of the light station buildings was removed. It shows the basic plan of the lighthouses clearly: a square central column with six graceful flying buttresses, supporting a large circular lantern room.

Caribou Island Light, Lake Superior

Canadian Coast Guard photo provided by Ron Walker

There is some disagreement between references as to the height of the Caribou Island Light but older references give the height as 104 ft (about 32 m). The tallest of the flying-buttressed towers, at 33 meters (108 ft), is apparently the Phare Pointe-au-Père near Rimouski, Québec. Although Point-au-Père has been inactive since 1975 it is preserved as a National Historic Site and the light station buildings now house a popular maritime museum, the Musée de la Mer. The lighthouse is completely restored and carries its original third-order Fresnel lens in the lantern. The museum and lighthouse are open daily from early June through mid October.

Phare Pointe-au-Père, Québec

Photo copyright Michel Forand; used by permission

Cape Norman Light

Dept. of Fisheries and Oceans photo

provided by Michel Forand

Belle Isle Northeast Light, Newfoundland

Canadian Coast Guard photo from Lighthouse Explorer Database

The nearby Belle Isle Northeast Light was built as a cylindrical cast iron tower in 1905. Three years later Anderson encased the tower in an octagonal concrete tower and added eight flying buttresses. This substantial upgrade made it possible for the lighthouse to support a much larger lantern and lens.

Canadian Coast Guard photo provided by Michel Forand