For fifteen months after the agreement made, the 16th December 1846, between the British Government and the Lahor Darbar, the Panjab remained apparently quiescent under the control and guidance of a British officer. That officer was not always Sir Henry Lawrence. After administering the affairs of the Sikh State for less than a year, that distinguished officer had, to recover his shattered health, accompanied the retiring Governor-General, Lord Hardinge, to England.

But during the few months of his tenure of office Si Henry Lawrence had laid down the principles upon which he proposed to guide and reform the administration of the Panjab, The chief of these was English supervision. With this object lie had deputed two of the ablest of the officers placed at his disposal – men already famous, and both of whom have an imperishable record in the Temple of Fame, Herbert Edwardes and John Nicholson – to Bannu, a district in the Derajat, north of Dera Ismail Khan, a portion of the Panjab territory, which, though nominally ceded to it by the Afghans, had neither been completely conquered nor thoroughly occupied. Ultimately it was arranged, Nicholson’s services being at the time required elsewhere, that Edwardes should proceed to Bannu alone, and this arrangement was carried out. It was a bold step indeed to send to a country which had never been properly subdued,

one month’s march from Lahor, to control its inhabitants, a solitary Englishman. But the result proved the correctness of the view taken by Sir Henry Lawrence, alike of the selected Englishman and of the feasibility of the task to him entrusted.

To other parts of the Panjab, likewise, Sir Henry deputed officers of his selection. His brother, George Lawrence,94 not the least able and the least distinguished of a very remarkable family, was sent to the still more distant post of Peshawar. Accompanying him was a promising young officer, Lieutenant Bowie, already noted for the sureness of his judgment. To Attock had been sent Herbert; to Hazarah, Abbott of the Artillery, the noblest and gentlest of men, endowed with a heart which comprehended all mankind, and who had previously, alone and unattended, made the romantic and dangerous journey from Herat to Khiva and Bokhara, and thence to the frontier of Russia, for the purpose of negotiating the freedom from slavery of Russian subjects detained in those countries; to other difficult districts, John Nicholson, already referred to, Lake, an officer of the Engineers, of cool and calm judgment, Reynell Taylor, Lewin Bowring, afterwards Chief Commissioner of Maisur, Cocks, and some others. The main instructions given to these officers were to report freely to Sir Henry regarding the state of the several districts, to resettle the country, to make recommendations as to reforms, and to do their best to maintain peace and order, and to instil confidence as to the intentions of the British into the people.95

It may well be doubted, judging from the knowledge we now possess, whether, even if Sir Henry Lawrence had remained at his post, the system of controlling the Sikh Darbar by means of reports received from British officers at the extremities of the Panjab could have long resisted the strong national feeling which was silently growing up throughout the country. The fact is that neither Lord Hardinge, Sir Henry Lawrence, nor any of the able coadjutors of the latter, recognised the fact that though the Sikh army had been decisively beaten at Sobraon, the Sikh people had never felt themselves subdued. On the very morrow of their great defeat, the soldiers, and the classes from whom the soldiers were enlisted, had recognised that they had been betrayed; that they and their country had been sacrificed to the chiefs who were now reaping the reward, thanks to the protection afforded them by the foreigner, of their combined cowardice and treason. At the very time, then, when the English officers I have enumerated were performing the dangerous duties allotted to them with marked success among the rude tribes on the extremities of the kingdom, within the Khalsa itself there was being nurtured a feeling which tended every day to render certain, at no distant day, a national rising.

It was not to be expected that the English officers deputed to outlying districts on the frontier, inhabited, be it remembered, not by Sikhs, but by tribes who had been subdued by the Sikhs, should realise the thoughts which coursed through the heart of the Sikh nation. They were, after time had allowed their true position to become understood, regarded for the most part as the friends of the tribes, as their protectors against the oppression of the nearest Sikh authorities. The officers in question, recognising this feeling on the part of the populations amongst whom their lot was cast, reported, with just pride, to Sir Henry the success of their mission. Nor is it to be wondered at that Sir Henry, coming in contact at Lahor

with the chiefs who had betrayed their own people in the late campaign, should consider that the reports of his officers justified him in looking forward to a long period of tranquillity in the province of which he had the control.

It is certain that unless Sir Henry Lawrence had been satisfied that affairs in the Panjab were progressing in a satisfactory manner, he would not have yielded to the wish expressed by Lord Hardinge that he should accompany him to England at the end of 1847; nor, unless Lord Hardinge had been impressed by the same view, would he have signalised the last few months of his administration by a reduction of the army; nor would his friends have declared, as they loudly declared on his departure, that there would not be another shot fired in India for another ten years.96

The successor of Sir Henry Lawrence was the Foreign Secretary of the Indian Government, Sir F. Currie. An able Foreign Secretary, Sir F. Currie had had little experience of administration, still less of the administration of a country peopled by a race of warriors only half subdued, and chafing every day under the recollection of the means by which they had been subdued; warriors, whose chiefs, the men whom he had to control, were as smooth-tongued, as slippery, and as oily as the subordinates with whom he had had to deal in the early days of his official life. Moreover, it must be recollected that, as Foreign Secretary, Currie had been the recipient of the secret reports of Lawrence, and that when he relieved him of his office he was prepared thoroughly to endorse the opinions regarding the tranquillity of the country to which Sir Henry had given utterance.

And yet the period in question was really most critical. Smooth as was the outer surface, the currents below were in violent commotion. The true Sikh leaders, the leaders who preferred independence to servitude, however gilded, had taken

their measures with the Sikh soldiery, and were waiting only for their opportunity.

It is just possible, seeing what sort of a man Sir Henry Lawrence was, that, had he remained at Lahor, the opportunity would not have been given, and that, under any circumstances, he would have dominated the situation. His noble bearing, his gentle manner, his lofty character, had already gained for him respect, and, it is not too much to say, in some cases, even affection, even from those who were plotting against the English. It is certain, moreover, that Sir Henry Lawrence would not have given to the confederates the opportunity of which they took advantage; as certain, that, had an outbreak occurred in his time, he would have met it in a different manner.

The crisis which occurred soon after Sir F. Currie had assumed the control at Lahor occurred in this wise:–

Mulraj, eldest son of Sawan Mall, had succeeded his father in 1844 as Diwan or Governor of Multan. The conditions of the succession were, that while the Diwan should transmit a certain fixed amount yearly to the Lahor Darbar he might keep for himself the remainder. These terms had been enjoyed by his father with so much advantage, that, on his death, after an administration of twenty-three years, he had left £900,000 to be divided amongst his sons!

On his accession, Mulraj was expected to pay to the Lahor Darbar a fee of thirty lakhs of rupees. He was quite prepared to pay that amount, but the Government at Lahor was in a state of revolution, and the matter stood over, therefore, until after the abortive invasion of India.

In 1816, after the close of the war, the Lahor Government, during the premiership of Lal Singh, demanded payment, and sent a detachment of troops to enforce it. Either confident in his strength, or imbued with contempt for the Darbar, Mulraj refused compliance, and, meeting force by force, defeated the Darbar troops near Jhang. The British then

intervened, and it was finally settled that Mulraj should give up the district of Jhang, north of Multan, and comprising nearly one-third of the province theretofore held by him; that he should pay twenty lakhs as the succession-fee; and that the revenues of the districts still left in his charge should be raised in amount by rather more than a third. Mulraj expressed himself well pleased with this arrangement.

Faithfully did Mulraj fulfil the engagements he then made. But he did not satisfy the Lahor Regency. Complaints reached that body and its controller, Sir Henry Lawrence, to the effect that the weight of Mulraj’s little finger was heavier than his father’s loins. Called upon to remedy the evils complained of, Mulraj fired up. The summons was, he contended, outside the agreement he had made with the Darbar, and which he had faithfully kept. He might have added that the revenue demanded from two-thirds of his father’s territory exceeding by one-third the amount which his father had paid from the whole, rendered necessary an increase of taxation. After some fruitless interchange of communications, Mulraj, on learning that Sir Henry Lawrence was about to leave for England, came to Lahor and tendered resignation of his office (November 1847).97

Sir Henry Lawrence had left Lahor for England when Mulraj arrived. Mr. John Lawrence, therefore, received him. With him, after much but fruitless persuasion not to persist in his idea, Mulraj came to the following agreement:– First: That his resignation should be accepted, but should be kept a profound secret from the Lahor Darbar. Secondly: That it

should take effect from the end of the following April, up to which time Mulraj was to account for the revenue. Thirdly: That two or three months before his actual ‘resignation, two British officers should proceed to Multan to be initiated by Mulraj into the state of the country, and ultimately to be installed by him in charge of it.98 This agreement settled, Mulraj returned to his government.

Sir F. Currie was unable to assume charge of the office held by Sir Henry Lawrence till the 6th March. Meanwhile, notwithstanding the engagement to secrecy, the story of Mulraj’s intended resignation had been noised abroad. The consequence was that when Sir Frederick arrived, considering the pledge to secrecy to be at an end, he insisted, against Mr. Lawrence’s remonstrance,99 on consulting the Lahor Darbar. Before doing so, however, he wrote to Mulraj to request him to withdraw his resignation. Mulraj refused. Sir F. Currie, then, in consultation with the Darbar, resolved to carry out the third clause of the agreement made between Mr. John Lawrence and Mulraj, and to send to Multan two English officers to be initiated into the affairs of the province. He selected for this purpose Mr. P. A. Vans Agnew, of the Civil Service, and Lieutenant W. A. Anderson, of the Bombay Fusiliers.

I must ask the reader always to bear in mind that Multan was, considered the strongest fortress in the Panjab; that Sher Singh, who subsequently led the popular movement, was a prominent member of the Regency, and believed to be extremely well affected to British interests; and that the word had been passed to all the able-bodied men in purely Sikh villages that the time was approaching when their services would be urgently required.100 With the knowledge of these incontestable facts it

is difficult, looking back, to resist the conclusion that the resignation of Mulraj, proposed the moment Sir Henry Lawrence had quitted Lahor, was part of a deep scheme to inveigle the English into hostilities, at the hottest season of the year, against the strongest fortress in the Panjab, to be detained there until the general rising, already determined upon, should be accomplished. The father of Mulraj, though of low origin, had been emphatically one of Ranjit Singh’s men. Mulraj had been brought up in the same school. In common with the Sikh nation, they loathed the idea of being dragged at the chariot wheels of the conqueror, who, they one and all believed, had not vanquished them in fair fight.

Still, however clear this may appear to us, who, with the knowledge of subsequent events, can trace their cause, it can easily be understood how it was a sealed letter to every Englishman at that time in authority. The arrangements made with respect to the Panjab were so perfect, the contentment of the people was so assured, the reforms introduced by the English were so popular, that it was heresy to dream of Sikh disaffection. And, in point of fact, no one on the spot did dream of it.101

With a light heart, then, Currie despatched Agnew and Anderson to Multan, there to be tutored by, and ultimately to relieve, Mulraj. To escort them there was detailed a body of about fourteen hundred soldiers of the Sikh army. Of these, the infantry, upwards of six hundred in number, were hill-men,

the troops least affected to the Khalsa, and therefore likely to be influenced by a display of manly qualities on the part of their officers; the cavalry, regular and irregular, Patans and Sikhs, numbered about seven hundred, and there was an excellent troop of horse artillery. The whole were commanded by a Sikh officer, Sirdar Khan Singh, who was to succeed Mulraj as Nazim, or Governor, of the Multan districts.

Regard being had to the fact that the infantry of the escort were hill-men, very lukewarm in their devotion to the Khalsa, wisdom would have dictated to the two British officers the advisability of accompanying them in the march to Multan. But the hot season had set in, and it was pleasanter to travel by water. By water, then, the two English officers and the new Nazim, Sirdar Khan Singh, proceeded, whilst the troops, left to themselves, marched by land. The result was, that, on the 18th April, the two parties, the troops and their commanders, met each other for the first time in front of Multan. They encamped then at the ‘I’dgah, a spacious Muhammadan building, within cannon-shot of the north face of the fort, and about a mile from Mulraj’s own residence, a garden house outside the fort, called Am Khas.

Into the events which immediately followed, it is not necessary to enter into great detail. They are very simple. Mulraj and the British officers exchanged visits on the 18th, and it was arranged that on the following morning Mulraj should make over the fort to Sirdar Khan Singh.

Early on the morning of that day that official and the two British officers, accompanied by Mulraj, entered the fortress; were shown all over it, received the keys, planted sentries from the men of their own escort, mustered Mulraj’s garrison, endeavoured to allay the sullen feeling of which they gave evidence at being thrown out of employment, and set out to return to their camp.

On their way, crossing the bridge over the ditch, one of the

late garrison, standing upon it, struck Agnew from his horse with his spear. Agnew jumped up to return the blow with his riding-stick, when the man rushed in with his sword and inflicted two severe wounds on the Englishman. A crowd collected: soon the news was noised in the fort; the late garrison came pouring forth, set upon Anderson and cut him down, leaving him for dead. Mulraj, at the first signs of tumult, put spurs to his horse, and forced his way to his private house. Anderson was carried, seemingly dead, by the men of his escort to the ‘I’dgah; Agnew was, about the same time, extricated from the mob by Sirdar Khan Singh, lifted on to his elephant, and conveyed to the same building.

Of the two Englishmen, Agnew was the less injured. In the trying situation in which he was placed he displayed the calmness, the courage, I might even add, the generosity, of his race. Unwilling to condemn Mulraj for an outbreak which might well have been caused by the fanaticism of a solitary soldier, he wrote to him (11 a.m.) to express his utter disbelief in his culpability, and to beg him to prove his good opinion by seizing the guilty parties and coming himself to the ‘I’dgah. Three hours later, as Mulraj gave no sign, Agnew despatched letters to Herbert Edwardes at Bannu, and to General van Cortlandt, Governor for the Sikhs of the province of Dera Ismail Khan, to ask for assistance. At 4 o’clock a message came from Mulraj to the effect that he could neither give up the guilty nor come himself, as he, after some efforts, had been forced to desist from attempting to control the storm; “that all the garrison, Hindu and Muhammadan, were in rebellion, and the British officers had better see to their own safety.”

The die, in fact, had been cast. Whether Mulraj designed that the outbreak should occur at that particular time, or in that particular manner, may be doubted; but, the outbreak having occurred, he had but one thought – to place himself at the head of the movement. The messenger who had conveyed

to Agnew the reply of Mulraj returned to find his master presiding at a council of his chiefs! That same night Mulraj, to prevent their flight, carried off the whole of the carriage cattle of the English officers and of their escort!

Agnew, undismayed, showed a bold front to the foe. He had still the escort and their six guns. If he and his comrade had only but marched with that escort and won their esteem! It was too late to think of that now! Still, he placed his guns and posted his troops in the manner best calculated to offer successful resistance. He made, too, one effort, unhappily fruitless, to induce the chiefs round Mulraj to obey the orders of the Lahor Regency. Presently guns opened upon his position, alike from the fort and the private house of Mulraj. Then emissaries came to tempt the escort. Despite of all the efforts of Agnew, they succeeded. Before the sun set all the troops – horse, foot, and artillery – had gone over, “except Sirdar Khan Singh, some eight or ten faithful horsemen, the domestic servants of the British officers, and the munshis of their office.”102

“Beneath the lofty centre dome of that empty hall (so strong and formidable that a very few stout hearts could have defended it),” continues the author from whom I have just quoted, “stood this miserable group around the beds of the two wounded Englishmen. All hope of resistance being at an end, Mr. Agnew had sent a party to Mulraj to sue for peace. A conference ensued, and, ‘in the end,’ say the Diwan’s judges, ‘it was agreed that the officers were to quit the country, and that the attack upon them was to cease.’ Too late! The sun had gone down; twilight was closing in; and the rebel army had not tasted blood. An indistinct and distant murmur reached the ears of the few remaining inmates of the ‘I’dgah, who were listening for their fate. Louder and louder it grew, until it became a cry – the cry of a multitude for blood! On they

came, from city, suburbs, fort; soldiers with their arms, citizens, young and old, and of all trades and callings, with any weapons they could snatch.”

Then was consummated the murder of the two gallant Englishmen. The head of Agnew was severed from his body, whilst Anderson, who, since he had been brought in grievously wounded from the fort, had been incapable of stirring from his bed, was backed to pieces with swords. Sirdar Khan Singh, faithful to the last, was conveyed a prisoner into the presence of Mulraj, laden with taunts and insults!

I have said that at 2 o’clock on the day on which he was assaulted, Van Agnew had despatched a letter, asking for aid, to Edwardes. The letter reached Edwardes at Dera. Fath Khan, ninety miles from Multan, on the afternoon of the 22nd of April. With the prompt resolution which ever characterised him Edwardes at once transmitted a despatch to the British Resident at Lahor, informing him of the attack made upon the two Englishmen, and announcing his own intention of marching upon Multan with the raw native levies103 of whom he could dispose. Leaving Edwardes, for the present, I must precede his letter to Lahor.

Sir Frederick Currie received the first news of the outbreak at Multan on the 21st of April. He rather made light of it, considered the affair unpremeditated, and that though Mulraj’s conduct was very suspicious, yet that his share in the outrage was doubtful. Impressed with the idea that Mulraj was very unpopular both with the army and the people, and that it was quite possible lie might have been urged to extreme measures by “unfriends”104 desirous of effecting his ruin, he deemed, at the moment, that the crisis would be adequately met by the despatch against Multan of a force composed of

seven battalions of infantry, two of regular cavalry, twelve hundred irregular horsemen, and three troops or batteries of artillery – all belonging to the Khalsa army – to proceed or be stopped according to the accounts he might receive in the next twenty-four hours. Such a force he despatched accordingly.

When, two days later, Currie received an account of the attack upon, but not of the massacre at, the ‘I’dgah, he was as fax off as ever from arriving at a just conclusion. Still implicitly trusting the Sikh sirdars, and wrongly attributing the movement to “Patan counsel and machination,”105 he directed the Sikh sirdars, “all the chiefs of the greatest note,” with the few Sikh troops at Lahor, to take part in the operations already ordered, intending to support them with the British moveable column, stationed at Lahor. The idea of a general conspiracy on the part of the Sikh chiefs and population never having entered his head, Currie was sanguine enough to believe that a demonstration only would be sufficient.106

The receipt, the next day, of a more complete account of the events at the ‘I’dgah, comprising the murder of the two British officers, caused another modification in the views of the Resident. The facility with which the Sikh escort had gone over to Mulraj, for the first time aroused within his mind that, possibly, the entire Sikh army might follow their example. He abandoned, then, at once, as impracticable, his dream of a demonstration, recalled the order given to the officer commanding the British moveable column, and informed the Sikh sirdars that they must put down the rebellion themselves!

The Sikh sirdars, all men, in the view of the British Resident, “implicitly to be relied upon,” did not view matters quite in the light in which they presented themselves to the mind of that high official. They declared themselves unable to coerce

Mulraj without the aid of British troops; and, admitting that their own men could not be depended upon, urged that they should not be employed at all in the operations against Multan. Sir F. Currie, then, recommended that the British army should itself undertake the operation, not in the interests of the Sikh Government, but – his mind curiously running on the Patan scare – to prevent the Afghans establishing themselves upon the Indus!107 On the same date he wrote to the Commander-in-Chief, Lord Gough, recommending that a British force should at once move upon Multan, capable of reducing the fort and occupying the city, independent of any assistance, or in spite of any opposition, from the Sikh troops.

Lord Gough, however, who was at Simla, conceived that at the advanced season of the year operations against Multan would be uncertain in their results, if not altogether impracticable. He therefore not only declined to commit himself to the plan urged by Currie, but even deprecated the weakening of Lahor in view to the very uncertain disposition of the Sikh army. In this view the Governor-General concurred.108

The siege, then, having been postponed till the autumn, it is time we should return to Edwardes. .

We left that officer at Dera Fath Khan preparing to march with his raw levies, numbering only about sixteen hundred men, against Multan. Between him and that fortress flowed two broad and rapid rivers. Writing to his friend Reynell Taylor at Bannu to send him a regiment of infantry and four guns “sharp,” he crossed the Indus, reached Leia on the 25th April, and was joined there by many of the Patan gentry of the neighbouring districts. Mulraj, hearing of this movement, sent a

force against him. On its approach Edwardes evacuated Leia, recrossed the Indus, and effected a junction, on the night of the 3rd May, with a Patan force under General Van Cortlandt. Four days later Mulraj recalled his army from Leia, and Edwardes at once occupied that place with a picket. Whilst Van Cortlandt, then, under orders from Lahor, proceeded to enter the trans-Indus territories of Mulraj, Edwardes waited at Dera Fath Khan till the situation between Leia and Multan should develop itself. Learning on the 15th May, from his picket, that a Sikh force had arrived within striking distance of that place, he crossed the Indus during the night with two hundred men, and, joining his picket, repulsed the enemy with the loss of all their zumburaks (falconets) and twelve men killed. Four days later the loyal Biluchis and Patans defeated the Sikh party near Dera Ghazi Khan, and took possession of that place for the English. This victory deprived Mulraj of all his Trans-Indus dependencies. Edwardes then occupied Dera Ghazi Khan, and watched thence the movements of the enemy. Learning at length that Mulraj’s best army had taken the field to secure the country between the Indus and the Chinab, Edwardes, now joined by the loyal Nuwab of Bahawalpur, marched against it, met it at the village of Kinairi on the Chinab, and, after a contest which lasted nine hours, completely defeated it. The effect of this victory was to deprive Mulraj of the country between the Indus and the China)), and of nearly all between the Chinab and the Satlaj. Following it up, Edwardes, reinforced by Van Cortlandt, and joined by Lake, pushed on towards Multan, met the last army of Mulraj, commanded by that chief in person, at Sadusam, close to the walls of the fortress, completely defeated it, and confined the enemy thenceforth to the city and its defences. They never again emerged from it except to resist the siege of the British army. This is not the place to do justice to the energy, the daring initiative, the greatness of character displayed by Herbert Edwardes. Alone, unsupported, he achieved a result of which

a British army might have been proud. And it is not too much to affirm that had he been then and there supported by a few British troops and guns, placed under his own orders, he might have taken the fortress, and possibly have nipped the rising in the bud!109

Meanwhile, whilst Edwardes and his gallant comrades were thus combating, with means of their own manufacture, against the chief who had revolted against the Lahor Darbar, Sir F. Currie was preparing, in concert with that Darbar, and in correspondence with the Governor-General and the Commander-in-Chief, for the autumn siege of Mullin. But before the autumn arrived, the horizon had become more clouded still. In the month of July a plot was discovered in which the Rani Janda, “who had more wit and daring than any of her nation,”110 was seriously implicated. The chief conspirators were brought to trial and were hanged, and the Rani was exiled to the fort of Chunar, there to be kept as a state prisoner. Information reached Lahor about the same time that the Hazarah was shaky, and that a suspicious movement had been observed in that province. Notwithstanding the confidence justly felt by Currie in Abbott, the English representative in the Hazarah, and the assurances of Chattar Singh, father of Sher Singh, a prominent member of the Lahor Council of Regency, that there was nothing really to be apprehended, there was sufficient disturbance in the air to cause great anxiety to a man in the position of the British Resident. Just at this crisis Currie was cheered by the news of the battle of Sadusam, and incited to action by the recommendations from Edwardes which accompanied that news. At once, then, on his own responsibility, he directed the British brigade at Lahor to march upon Mullin. Currie’s conduct in this respect was confirmed very

grudgingly by the Governor-General. As for the Commander-in-Chief, in the promise of facility and aid he despatched to the Resident he took care to remind him that the troops had been ordered to move upon his responsibility. Upon Lord Gough, however, it devolved to arrange for the strength and composition of the British force to be employed.

It was speedily decided that the Lahor brigade should be reinforced by that at Firuzpur. The force would then consist of about seven thousand five hundred men, including two European regiments, the 10th and the 32nd, with a proportion of artillery, including a siege train, and cavalry, and would be commanded by General Whish, the commander of the brigade at Lahor. Currie, meanwhile, in concert with the Regency, had decided to despatch a purely Sikh force to Tolomba, under the command of the ablest of its members, Sher Singh Atariwala. This force, consisting of about five thousand men, was not, however, content with marching to Tolomba, but pushed on, on the 6th July, to Multan.

Whish left Lahor with his brigade on the 24th July, and encamped at Sital-ki-mari, before Multan, on the 18th August. The following day he was joined by the Firuzpur brigade, commanded by Brigadier Salter. Whish found Edwardes’s army, now composed of fourteen thousand infantry and over eight thousand irregular cavalry, encamped at Surajkund, about six miles distant. His first care was to lessen that distance by bringing Edwardes two miles nearer to the fortress, a movement which was not accomplished without some hard fighting, in which Lake and Pollock – now Sir Frederic Pollock – distinguished themselves.

Pending the arrival of the siege train, Whish and his chief Engineer, Major Napier – now Lord Napier of Magdala – closely reconnoitred the fort. The two officers named, with a small party of the staff, crept forward into the ‘I’dgah, and thence made a leisurely observation. They emerged with the conviction

that “it was no contemptible place of arms.” They could do nothing, however, till the arrival of the siege guns, and those guns reached the camp only on the 4th September.

But before their arrival an event occurred which greatly affected the course of action. The threatened outbreak in the Hazarah had taken place, and Chatter Singh, father of the Sher Singh who commanded the Darbar troops before Multan, had placed himself at the head of it. It is true that Sher Singh cleared himself, in the opinion of Lieutenant Edwardes, from any complicity in his father’s conduct; but the fact that that father was at the moment at the head of a great national movement was not encouraging. Under these somewhat unfavourable auspices, the siege of Multan began (7th September 1848). I do not propose to coo more than give a summary of it. On the 9th, a night attack made upon some gardens in front of the trenches, though conducted with great gallantry, and illustrated by the splendid valour of Lieutenant Richardson, of the Indian Army, and of Captain Christopher, of the Indian Navy, both of whom showed the way to their followers, was repulsed.111 On the 12th, Whish, after a very hot encounter, productive of loss on both sides, especially on that of the Sikhs, cleared his front, gaining a distance in that direction of eight or nine hundred yards, and driving the enemy into the suburbs. The place seemed now at the mercy of the British general. He was within easy battering distance of the city walls. A few days more, and Multan would have been his. But, just at this critical moment, he was baffled by an action which, though foreseen by some acute minds,112 had not been provided against. On the morning of the 14th September, Sher Singh and his whole force gave their adhesion to the national movement, and entered Multan!

In consequence of this defection General Whish at once raised the siege, but remained encamped before the place, at first on the field of Sadusam, later on a more convenient spot close to the suburbs of the town, waiting for reinforcements or orders: He remained there inactive, but still in a way blockading the town, till the 27th December, when, reinforcements having arrived, he resumed the siege. Long before that period the decisive action of the national movement had passed to another part of the country. To that part I propose, now, to transport the reader.

The rising of Chattar Singh, the defection of Sher Singh, the consequent raising of the siege of Multan, brought matters in the Panjab to a crisis. There could no longer be any doubt. The Khalsa had resolved to strike a great blow for independence.

The Government of India was neither blind nor deaf to the signs of the time. The Governor-General, Lord Dalhousie, in a famous speech delivered at Barrakpur, which resounded all over India, declared that as the Sikh people wished war “they should have it with a vengeance.” The Commander-in-Chief, Lord Gough, issued, early in October, a general order announcing the formation, at Firuzpur, of an army, to be styled “the army of the Panjab,” under his own personal command.

Whilst this army was assembling, Cureton with a brigade of cavalry, and Colin Campbell113 with a brigade of infantry, were directed to march from opposite directions on Gujranwala, a small fort about three days’ march from Lahor, which it was expected the Sikhs would occupy. Cureton, who arrived there first, found the place unoccupied. So much, at this time, did the British undervalue their enemy, that a very general impression prevailed that if Cureton and Campbell had pushed on from Gujranwala they would have finished the war!

Similarly Brigadier Wheeler’s brigade, which, since the month

of August, had been engaged, under the direction of Mr. John Lawrence, in putting down the national movement in the Jalandhar Doab, and Brigadier Godby’s brigade, were pushed on, about the 3rd of November, towards the Ravi.

The entire army formed by Lord Gough, including the three brigades already mentioned and the division under General Whish still before Malian, was composed of seven brigades of infantry, four of cavalry, and a numerous artillery. It numbered about seventeen thousand infantry and four thousand cavalry. Of the former arm, however, between four and five thousand were with General Whish. The army, then, which Lord Gough found under his own immediate direction when, after crossing the Satlaj and the Ravi, he arrived at the small village of Noiwala, thirteen miles from the Chinab, on the 20th of November, consisted of about twelve thousand five hundred infantry, of whom one-fourth were Europeans, and three thousand five hundred cavalry, comprising three British regiments.114

Ten miles from the British camp, and three only from the banks of the Chinab, near the walled town of Ramnagar, lay detachments of the Sikh army. They were encamped in an open plain covered with a low scrub jungle extending to the river. Midway between their position and the river was a small grove.

The position was admirably chosen. From it the Sikh commander, who was no other than Sher Singh Atariwala, whose desertion to Mulraj had caused the raising of the siege of Mahan, could intercept the movements of the ruler of Kashmir, Gulab Singh; could cover his communications with his father in the Derajat; and could draw his supplies from the productive districts in the upper part of the Chinab. Such a position was

worth fighting for. Indeed, Sher Singh would have been justified in seeking an opportunity to bring the British to action to maintain it.

Apparently, however, Sher Singh regarded the ground about Ramnagar as not worth fighting for. For, when, on the morning of the 22nd of November, Lord Gough moved with a force composed of cavalry and artillery, supported by an infantry brigade115 and two batteries of artillery, to reconnoitre the position of the enemy, Sher Singh directed the detachments on the left bank to recross the river by the ford and to rejoin him on the right bank.

Lord Gough belonged essentially to a “fighting caste.” In the presence of an enemy he could think only of how to get at him. At that time of supreme excitement all ideas of strategy, of tactics, of the plan of the campaign, vanished from his mind. How a momentary triumph might be gained became his dominant and fixed thought. On the occasion of which I am writing a calm and cool leader would have rejoiced to see an enemy voluntarily abandoning, in the face of a military demonstration, a splendid military position, and retreating to a country where supplies were difficult and whence he could not control the ruler of Kashmir. He would even have aided him by making the demonstration more pronounced. But no thought of that kind ever entered the brain of Lord Gough. He had joined and placed himself at the head of the advanced party of cavalry that morning “unknown to the majority of his staff,”116 and he now saw the enemy retiring without his striking a blow! Little reeked he of the fact that his own advanced

party was few in numbers, that he had left the main body of his troops behind him without orders and without a head; it never occurred to him to reflect that in all probability the Sikhs were but retiring to a selected position, covered with heavy guns, on the right bank of the river. He thought of nothing but that the enemy were escaping him when they were within measurable distance of his small force. Rendered wild at this thought he dashed his cavalry and horse artillery at them as they were crossing the ford.

The horse-artillery guns of Lane and Warner, opening upon the enemy engaged in a movement of retreat, caused them at first some slight loss; but as the British guns pressed on, they came, as might have been expected, under the fire of the enemy’s guns on the right bank, a fire so superior to their own that their position became untenable. The English then endeavoured to retire. But this had become a matter of great difficulty. Their guns, one of them especially, had become deeply embedded in the heavy road of the river bank. It was difficult to extricate them, and, after superhuman efforts, the English, to save the remainder, were forced to abandon that one.

To cover the retreat of the British artillery Captain Ouvry, with a squadron of the 3rd Light Dragoons, made a gallant charge on a body of the enemy who had taken up a position on an islet surrounded by stagnant pools. This charge was followed by others; but the Sikh infantry, cool and resolute, maintained on the cavalry a galling fire, and then, as the charges ceased, advanced to capture the abandoned gun.

Burning with indignation at the very idea of the enemy carrying off a trophy in the very first action of the campaign, Colonel Havelock, commanding the 14th Light Dragoons, demanded and obtained permission to drive the enemy back. The 14th, accompanied by the 5th Native Light Cavalry, charged, then, upon the advancing Sikhs with so much fury

that they rolled them back in disorder. Hoping then to recover the gun, the 14th pursued their advantage, and dashed forward to the ground on which it lay. But here, not only did the heavy sand tell on the horses, but they came within range of the batteries on the right bank. Under cover of this fire, too, the Sikh infantry rallied and returned to the charge. In the fight that followed Havelock was slain. Cureton, who had witnessed the charge, galloping down to withdraw the 14th from the unequal contest, was shot through the heart. The cavalry then fell back, leaving the gun still in the sand. During the day the enemy succeeded in carrying it off.

Such was the combat of Ramnagar, an affair entailing considerable – the more to be regretted because useless – loss on the British army. The object aimed at – the retirement of the Sikhs to the right bank – had been gained by the mere display of the British troops. The subsequent fighting was unnecessary butchery, which caused the loss to the British army of two splendid officers, Cureton and Havelock, and eighty-four men, killed, wounded, and missing. Besides this, it gave great encouragement to the Sikhs, who could boast that in their first encounter they had met the British not unequally.

The Sikhs, having crossed to the -right bank of the Chinab were now in the strong but inhospitable territory between that river and the Jhelam. A really great commander would have been content that they should remain there, eating up their scanty supplies, until Multan should have fallen, when, with a largely increased army and greatly enhanced prestige, he could assail them with effect. The true course and position of the English commander, was, in fact, to use the language of the most competent critic of the time, “marked out by the manifest objects of the enemy. To remain in observation on the left bank of the Chinab; to regard himself as covering the siege of Multan and holding Sher Singh in check till that place fell; to cover Lahor and cut off all supplies from the districts on the left bank of

the Chinab reaching the enemy; jealously to watch the movements of the latter, whether to the northward or southward: these should have been Lord Gough’s objects. So long as Sher Singh was disposed to have remained on the right bank of the China, Gough should have left him undisturbed, and patiently have awaited the fall of Multan117.”

But Gough cared for none of these things. He saw only the enemy. The enemy being on the right bank, he must cross to that bank and get at him. His mission, as he read it, was to seek the enemy wherever he could be found, attack him, and beat him. Larger aims than this lay outside the range of his mental vision.

The English general prepared, then, to dislodge the enemy from the right bank, and to cross the China. To make a direct attack on his position would have been dangerous; for the right bank was considerably higher than the left, and the ford across it was covered by a very powerful artillery. But rivers rarely present a serious obstacle to a resolute commander. This was especially the case with the Chinab in the cold months of the year, for at that season the stream contracts itself to a comparatively narrow channel, fordable in many places. It was not difficult, therefore, for Lord Gough to turn the position of the army which faced him on the right bank.

Between Ramnagar, which had now become the head-quarters of the British army, and the town of Vazirabad, some twenty-five miles to the east of it, on the same side of the river, were three fords across the Chinab – the fords of Ghari, of Ranikan, and of Ali Sher; the first-named being eight, the others about thirteen, miles distant from the British camp. There was also a ford

opposite Vazirabad itself. Lord Gough had before him, then, a choice of passages across the river.

But, extraordinary fact although, as I have shown, time did not press him, although sound policy would have induced him to remain altogether where he was, yet so eager was Gough to “get at” the enemy, that he would not spare a single day to have the fords I have named properly examined.118 He would appear to have been satisfied with the report of his staff that the fords were practicable, but that they were strictly watched by a numerous and vigilant enemy. Such “strict watching” has not, under other leaders, prevented British officers from making the strictest examinations. There was plenty of time for such, for, anxious as was Gough to look the enemy in the face, he could not put in action the turning movement till the heavy guns should have arrived, and those reached him only on the 30th November.

The very next day Lord Gough directed his divisional general of cavalry, Sir Joseph Thackwell, to march, at 1 o’clock in the morning, with the force destined for the turning movement, upon the ford of Ranikan. His force consisted of three troops of horse artillery, two light field batteries, two 18-pounders; of the 3rd Light Dragoons, the 5th and 8th Native Light Cavalry, the 3rd and 12th Irregulars; of the 24th and 61st Regiments of the Line, and of the 25th, 31st, 36th, 46th, 56th, and four companies of the 22nd Native Infantry – in all about eight thousand men. It was accompanied- by a pontoon train. The infantry was commanded by Brigadier-General Sir Colin Campbell.

Thackwell had resolved to cross by the ford of Ranikan on the ground that, being further from the position of the enemy than that of Ghari, it would not be so fiercely disputed; but,

to make assurance doubly sure, he detailed a small force to secure if possible the ford in front of Vazirabad.

To assure the success of the movement Thackwell was undertaking, silence, secrecy, and despatch were absolutely requisite. All three, on this occasion, were conspicuous by their absence.119 Not only did the camp-followers raise an astounding din, but the infantry, unprovided with a guide, became entangled in the intricacies of the vast camp, and finding it impossible, owing to the intensity of the darkness, to see, and difficult to feel, their way, did not reach the rendezvous till two hours after the appointed time. As a natural consequence, the turning force, instead of reaching Ranikan at eight o’clock, as had been laid down in the programme, arrived there only at eleven o’clock.

Thackwell rode to the front to reconnoitre. The view that met his gaze was not encouraging. He saw before him a broad river-bed – far broader here than in front of Ramnagar – the water flowing swiftly over which was divided into four separate channels, with sandbanks, and, as the natives reported, with dangerous quicksands. The opposite bank was out of range and was guarded by the enemy.120

Thackwell, Colin Campbell, and other high officers, spent three hours in debating the course to be pursued. Evidently the ford of Ranikan presented great and previously unthought-of difficulties. By degrees one and all recognised the impossibility of attempting it. Campbell then counselled a return to camp, but Thackwell, wishing to prove the matter to the utmost, resolved to attempt the ford at Vazirabad. He accordingly resumed the march, and reached his destination at six o’clock in the evening.

Here, too, but for the fortunate unforeseen and unexpected, he might have been again disappointed. But this time a good genius, in the shape of a man who, already great, afterwards astonished the world by his brilliant feats of war, the illustrious John Nicholson, had made his task easy. John Nicholson was at this time a political officer attached to the head-quarters of the army, for the purpose of facilitating the communications of its chief with, and of bringing his own influence to bear upon, the nobles and people of the country. On this occasion, foreseeing the difficulties which might possibly baffle Thackwell at the fords, Nicholson had ridden forward with a few of the Patan horsemen whom he had raised and trained, and secured at Vazirabad seventeen large boats. These constituted the acceptable present which gladdened the heart of Thackwell as he rode into Vazirabad.

Darkness had already set in. It was one great fault of the Sikh army, as apparent in this campaign as in that which was concluded at Sobraon, that they trusted too much to the darkness of the night. Not accustomed to attempt night surprises themselves, they posted no guards. But for this, under the circumstances, Thackwell might have been again baffled. The darkness of the night and the neglect of the Sikhs, however, greatly befriended him.

Thackwell wisely resolved to take advantage of these two circumstances to cross at once, and gain a footing on the right bank.

The result showed how fatal would have been the attempt had the enemy been on the alert. On the assurance of Nicholson’s Patans that the enemy were not watching on the other side, the guns were first crossed over. Of the two brigades of infantry, one, Pennycuick’s, then passed over in the boats. The other, Eckford’s, attempted wading; but, after mastering the first and second branches of the stream, they were brought to a dead stop by the third, and were forced to bivouac for

the night on a sandbank. Of the cavalry, Tait’s Irregulars crossed the ford as indicated by stakes: not, however, without the loss of some men from drowning.

The troops who had crossed, as well, it can easily be imagined, as those who had stuck half-way, passed a miserable night. They were all more or less wet; the cold was the intense, cutting cold of a Panjab December night; they had eaten nothing, or but little, all day; they had no food with them, and they were unable to light fires lest they should attract the enemy. The agony of such a situation is simply indescribable.

But the darkest hour comes to an end. With daylight, and the glorious sun which soon followed daylight, the men revived. They had at least an undisturbed footing on the right bank, and their comrades were crossing. Food would soon give them back their strength, and a brisk march restore their circulation. At length, by about noon, all the force had passed over except the 12th Irregulars and two companies of the 22nd Native Infantry. These were detailed to escort the useless pontoon train back to Ramnagar.

It was 2 o’clock before the men had finished their meal and were ready to march. Meanwhile Thackwell and Colin Campbell were discussing the line of advance to be adopted. They knew nothing of the country in which they were. They had only, then, to push on by the compass in the direction of the enemy. They marched that afternoon about twelve miles, to Duriwal, without encountering the Sikhs. There Thackwell received a message from Gough congratulating him on his successful passage, and urging him to attack the enemy in flank the following day, whilst he should assail him in front.

The next day this order was countermanded. After marching six miles, Thackwell received a despatch from the Commander-in-Chief forbidding him to attack till he should be joined by Godby’s brigade, which was to cross at the ford of Ghari. To facilitate this junction, Thackwell then directed his march

towards the three villages of Tarwalur, Rattai, and Ramukhail; but, too intent on the idea of holding his hand to Godby, he made the mistake of not occupying the line of those villages, and of throwing out his advanced guards and pickets well in front of them.121 Instead of so doing, he encamped on the grassy plain in front of the larger village of Sadulapur, having the three villages I have named in front of him.

Whilst they are breakfasting, let us cross the river and see what Lord Gough was doing at Ramnagar.

Lord Gough, we have seen, had despatched Thackwell to effect the turning movement early on the morning of the 1st December. It was not till midday of the 2nd that he learned the complete success of the operation. To distract the enemy’s attention from Thackwell, then, he immediately opened a heavy fire upon the enemy’s position on the opposite bank. The Sikhs replied by directing a return fire from the few guns which effectually guarded the ford, and which were so placed, that, though the fire of the British artillery was admirable, it could not, from the width of the river, silence them.122

Whilst the artillery fight was thus raging, Sher Singh was made aware of Thackwell’s successful passage and his subsequent movement. The idea which flashed across his mind was an idea worthy of a great commander. He resolved to march at once to crush Thackwell before Gough could possibly come to his support. He would then deal with Gough.

He broke up his camp, then, without delay, and drew back his whole force about two miles, preparatory to the contemplated movement. Meanwhile he gradually slackened his artillery fire against the British, until at length it ceased altogether.

But the movement to the rear was scarcely effected when other thoughts came over the mind of the Sikh leader. What if Lord Gough, encouraged by the cessation of fire, should cross

at once? He would be between two fires. He somewhat modified his plan, then, and, leaving the larger moiety of his forces to amuse Gough, marched with ten thousand men against Thackwell. This change in resolution was a half measure, and in war half measures rarely succeed. The action of Lord Gough proved that audacity on this occasion would have been justifiable. For that general, completely deceived, renounced the idea he had communicated to Thackwell, of immediate crossing. He spent the night of the 2nd in pushing forward breastworks and batteries, just as if a formidable enemy had been in front of him. It was not till the night of the day following that he discovered the abandonment by the enemy of his position, nor was he able to bring his army to the opposite bank till after Sher Singh had met Thackwell and was taking up a new position on the left bank of the Jhelam! Audacity was, therefore, not wanting on one side only.123

Whilst Gough was thus throwing up his earthworks and his batteries, Sher Singh was marching against Thackwell. He caught him about 11 o’clock on the 3rd, just as the English leader had taken up the position I have already described, in front of Sadulapur and behind the three villages. Thackwell’s men had but just piled arms and fallen out, when, suddenly, a peculiar sound was heard overhead, and, on looking up, a shell was discovered bursting in mid-air, between the British line and the villages in front – a distance of about half a mile of level turf. After this came round shot.124 It was Sher Singh who had thus surprised the British, badly posted facing three villages which he now held. In that supreme hour he must have deeply

regretted that he had not brought with him his whole army! The English troops at once fell in. The infantry deployed, and the advanced guard, which by this time was about equidistant between the enemy and the British main body, was ordered to fall back. When this had been accomplished, Thackwell, in order to have a clear space in front of him, retired about two hundred yards further.

Meanwhile, Sher Singh, still wanting in audacity, had contented himself with holding the three villages, and in pouring in a continuous fire from his guns. This fire could not have failed, under ordinary circumstances, to produce a murderous effect; but on this occasion its result was minimised in consequence of the precaution taken, on the advice of Colin Campbell, by the British general, to make his infantry throw themselves on the ground.

For nearly five hours the British force sustained this fire without replying. At last, at nearly 4 P.M., Thackwell’s patience was exhausted, and he ordered his guns to reply. The artillery duel then continued till sunset, varied only by two feeble attempts made by the Sikhs to turn both flanks of the British force. That on the left was baffled by Biddulph’s Irregular Cavalry and Warner’s troop of Horse Artillery, supported by the 5th Light Cavalry; that on the left by Christie’s Horse Artillery, the 3rd Light Dragoons, and the 8th Light Cavalry.

By sunset the firing on both sides ceased, and Sher Singh, still haunted by the fear lest Gough should take advantage of the night to cross, fell back on his position without loss and without pursuit. The loss of the British was only seventy-three.

Such was the artillery combat of Sadulapur, dignified, in the inflated language of the British commanders of the day, with the name of a battle. It must be a strange kind of battle in which, by the admission of the general, “the infantry had no

chance of firing a shot, except a few companies on the left of the line,” to repulse a turning movement, and the cavalry never charged, No, Sadulapur was nothing more than an artillery combat. The armies never came to close quarters; the English, because Sher Singh held a very strong position in the three villages, and the ground between them and their position was unfavourable to an advance; the Sikhs, because their leader feared to commit himself to a battle when he might, at any moment, hear the guns of Lord Gough thundering on his rear. There can be no doubt but that his want of audacity in not bringing up his whole army lost him a great opportunity; for no position could have been weaker than that of the English – and in war opportunities do not return.125

Meanwhile, Lord Gough, still encamped at Ramnagar pending the construction of a bridge of boats across the Chinab, had, on the 4th, despatched Sir Walter Gilbert with the 9th Lancers and the 14th Light Dragoons to the right bank of that river. Gilbert returned to report that the enemy had disappeared. Sher Singh had, in point of fact, fallen back during the night of the 3rd on his main body, and, in view of taking up a new position on the Jhelam, had marched a few miles in that direction.

“The ill-advised passage of the Chinab,” writes the most competent critic of this campaign,126 “the failure to strike a blow, and the withdrawal of the enemy intact to positions of their own choosing, were doubtless sufficiently irritating” to the British commander-in-chief. If the passage of the Chinab was to be justified at all, it could only be justified by following it up by a rapid advance on the enemy. Under the circumstances it was simply a useless piece of bravado. In spite of it, Gough with his main army was still chained to the left bank; he had no reserves; the commissariat arrangements were still incomplete; a feeling of insecurity was beginning to arise in Lahor; Multan was still unsubdued; Wheeler’s brigade was still busy in the Jalandhar Dab. In spite of Lord Gough’s bulletins, which imposed upon nobody, it was universally felt that up to that point the campaign had been a failure.127 The public, in fact, had lost all the confidence they ever possessed, never very much, in the military capacity of Lord Gough.

Nor, with time, did matters improve. After his affair at Sadulapur Thackwell had pushed on, in a blind sort of manner, after the enemy. He had been joined by Godby’s brigade at 9 a.m. of the 4th, and by the 9th Lancers and 14th Light Dragoons on the evening of the same day. On the 5th he moved to Helah, a mud village which had arisen on the accumulated debris of other villages. From this place, if he had only known it, Sher Singh and his army were distant only ten miles. But, so vicious was the system of reconnoitring, and so hostile to the English was the feeling of the people, that although Thackwell sent out two large observation parties of cavalry and artillery, these returned to camp only to report that they had seen, indeed, small bodies of the Sikhs, but that the villagers persistently asserted that Sher Singh had already crossed the Jhelam.

On the 18th December, the bridge of boats being ready, Gough crossed to the right bank, and marched forthwith to within three miles of the position which Thackwell still held at Helah. Sher Singh, well informed of the British movements, thought the moment opportune to march on Dinghi, a post from which he threatened the ford at Vazirabad and Vazirabad itself. He so imposed upon the English general that the latter resolved on the moment to fall back on Gujrat, and actually sent orders to Thackwell to support him in that movement. Under inspiration happier than his own, however, he cancelled the order, and despatched instead a brigade of cavalry and three guns to guard the ford. The army remained in Helah and its immediate vicinity.

The Governor-General, Lord Dalhousie, had been very unwilling to give his sanction to a general attack upon the main Sikh army until Multan should have fallen. His position in this respect was not very logical. Holding the views he did, he should have kept the British army on the left bank of the Chinab. Once having allowed Gough to cross, he should have urged him to immediate action. By his steering a middle course, by his allowing Gough to move to the right bank and then holding his hand, there came about a state of affairs which might be regarded almost as alarming.

Gough was still halted at Helah, when, in the beginning of January, the important fortress of Atak on the Indus, held till then by Lieutenant Herbert, surrendered to the Sikhs. The fall of Atak effected an immediate change in the views of Lord Dalhousie. Regarding it as an event which let loose the besieging army led by Chattar Singh, father of the Sikh commander-in-chief, and which opened the way for the advance of an Afghan contingent, for which it was known that chief had been negotiating, he at once, 10th January, sent pressing orders to Gough to strike, if he should deem himself strong enough, an effectual blow at the enemy in his front, and to strike it “with the least possible delay.”

In consequence of these instructions Gough broke up his camp near Helah, and advanced, at daylight on the 12th, to Dinghi, some twelve miles distant. Here he received information, subsequently proved to be true, that the Sikh army was in position some fourteen miles distant, that its left rested on the low hills of Rasul its centre on the village of Fathshah-ki-chak, its right on Ming.

That afternoon Gough summoned some of the officers whom he most trusted to confer with him on the best mode of carrying out the Governor-General’s instructions. Amongst the officers so summoned was one who had but recently joined the camp. The high character borne by this officer more than warranted the extension to him of the summons to attend the meeting, and it was upon the advice he gave that the commander-in-chief decided to act.

The officer in question – after alluding to the fact, a report of which had been made to head-quarters, that though the front of the enemy’s position was covered by a thick belt of jungle, yet along the frequented road which led from Dinghi straight upon Ras it the country was more open – pointed out that a line which extended from Basal to Mung must be thin and weak, and recommended, therefore, that the British army should march on Rasul and, taking the enemy in flank, should double up his line, thrust it back upon Fathshah-ki-chak and Mung, into a country void of supplies, where he would be hemmed in between rivers he could not cross, and thus cut him off from the fords of the Jhelam, sever his communication with Chattar Singh and with Atak, and render it impossible for him to receive further aid in men and provisions. This plan, constituting an echelon attack quite in the style of the Great Frederic,128 was, I have said, adopted by Lord Gough.

In the chapter immediately preceding, when I introduced Lord Gough to the reader, I described him as a general the

reverse in one respect of Clive, of Adams, of Wellesley, of Masséna, and of other great captains who were remarkable for their clearness of vision and coolness under the roar of cannon, inasmuch as he, under the same circumstances, forgot all his previous plans and sought only to get at the enemy. The events which followed the deliberations of the 12th January illustrate this remarkable feature of his character.

Gough had resolved, I have said, on an echelon attack on the enemy. It was intended that Gilbert’s division, forming the extreme right, should force the left of the enemy, whilst “the heavy and field artillery, massed together, should sweep in enfilade the curvilinear position of their centre and right”; that then, as soon as Gilbert had shaken and broken up the left, Campbell, till then kept in reserve with the massed artillery, should, with Gilbert and the cavalry, “throw himself fairly perpendicularly across the left centre of the opposing force, and hurl it to the southward.”129

Full of carrying out this plan, Gough marched from his ground early on the morning of the 18th January. “It was one of those pleasant mornings,” writes Captain Lawrence-Archer, himself a combatant, “peculiar to the cold season of upper India. The air was still and bracing, and the increasing warmth of sunshine, in an almost unclouded atmosphere, produced the glow so welcome after the cold of the early dawn.” After proceeding five or six miles, Gough halted and sent on the Engineers to reconnoitre. They returned about 10 o’clock to report the road clear and practicable for guns, and that the enemy were marching down from Rasul apparently to take up a position in the plain. The view which had been urged upon him being thus confirmed, Gough pushed on along the road to Rasa He had not, however, progressed very far when deserters informed him, through the political agent, Major Mackeson, that the enemy were in some strength on the left of the British

advancing column in the neighbourhood of the villages Mujianwala and Chilianwala. On receiving this information, Gough, renouncing the plan of the previous evening, quitted the Rasul road and inclined to the left. Further information having made known to him that small detachments of the enemy’s horse had been visible on the plain in advance of the mound and village of Chilianwala, and their infantry on the mound itself, he turned directly to the left and marched straight on that point, leaving the Rasul road in the rear of, and parallel to, his line when it was deployed.130

The Sikh detachment at the mound of Chilianwala, for it was no more, did not await the threatened attack, but fell back precipitately upon its main line by the idling road. Gough speedily gained the vacated mound, and from its summit obtained a good view of the enemy’s position. To bring his army in front of and parallel to it he had to bring his left forward. Whilst this movement was being effected he had time to examine in detail the enemy’s position. He saw them – to the number of about twenty-three thousand131 – their right facing Chilianwala, about two miles from that village, but less from the British line, which was deploying about five hundred yards in front of it, their left resting on the high ground of Rasul. There was a great interval between the left of their right wing and the right of the centre. “It was evident,” writes Durand, “that the enemy occupied a position too extended for his numbers.” His extreme right was refused, and inclined back towards Mung.

When the British army had deployed it was noticed that its line of infantry, solid and compact, did little more than oppose a front to Sher Singh’s centre. It is true it somewhat overlapped it, with the result, however, that its left brigade (of Campbell’s division) faced the gap of which I have spoken as existing between the Sikh right wing and centre.

Gough had no intention of engaging. It was 2 o’clock in the afternoon, and his troops had been under arms since daybreak. He gave orders, therefore, to his Quartermaster-General to take up ground for encampment. Meanwhile, pending the completion of that officer’s labours, the troops piled arms.

But Sher Singh was determined to force on a battle that afternoon. Knowing the temperament of the British commander, that the fire of artillery was the music which would make him dance, he despatched to the front a few light guns and opened fire on the British position.

The fire was distant and the effect innocuous, but the insult roused the hot Irish blood of the leader of the English army. It “drew” him, in fact, precisely in the manner designed by Sher Singh. He at once directed his heavy guns to respond, from their position in front of Chilianwala, to the fire of the enemy. The distance from the enemy’s advanced guns was from fifteen to seventeen hundred yards. Yet the density of the jungle prevented the English gunners from getting any sight of the Sikhs, and they had to judge their distance by timing the seconds between the report and the flash of the hostile guns. Their fire failed to silence that of the enemy, for Sher Singh, determined to complete the drawing operation he had so well begun, sent the whole of his field artillery to the front, and, the Sikhs, excellent gunners, maintained an equal contest with their foe.

This was more than Gough could stand. A thorough believer in the bayonet, and looking upon guns as instruments which it was perhaps necessary to use but which interfered with real

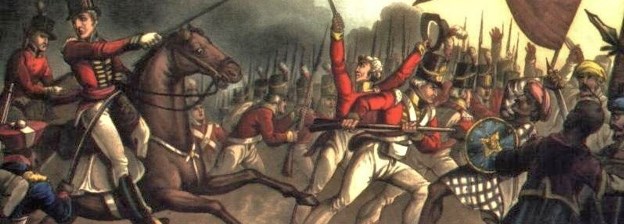

The Battle of Chilianwala, 13 January 1849

fighting, he, wild with excitement, ordered his infantry to advance and charge the enemy’s batteries.

The order of the English line was as follows:– Of the infantry, Sir Walter Gilbert’s division occupied the right, but he was flanked by Pope’s brigade of cavalry, strengthened by the 14th Light Dragoons, and three troops of artillery under Lieutenant-Colonel Grant. In the centre were the heavy guns under Major Horsford. The left was formed of General Colin Campbell’s infantry division, flanked by White’s brigade of cavalry and three troops of horse artillery under Lieutenant-Colonel Brind. The field batteries were with the infantry divisions, between the intervals of brigades. The reserve was commanded by Brigadier Penny, and Brigadier Hearsey protected the baggage.132

The reckless nature of the order given by the Commander-in-Chief – viz. to carry the guns in front at the point of the bayonet – may be judged from the fact that between those guns and the troops on the British left who were to carry them was very nearly a mile of dense and unknown jungle. However, British soldiers, well led, shrink from no impossibility; and on this occasion the divisional commanders, at all events, were men of tried experience and ability. Gough’s orders, then, were obeyed. The British line pressed on. I propose first to accompany the left, led by Colin Campbell.

I have stated that Campbell’s left brigade (Hoggan’s) overlapped the right of Sher Singh’s centre, and faced, therefore, in the original formation, a blank space. Pushing on towards the enemy, the right brigade then naturally came full in front of Sher

Singh’s right centre, which had been strengthened by many guns. Though the fire of these guns had been rapid,133 the brigade had suffered comparatively little, until, breaking out of the jungle, it came to a more open space in front of the guns. Now the storm of shot and grape thickened, and the gallant brigade charged; but the jungle had necessarily disordered the formations, and, having to charge over about three hundred yards, the men were winded before reaching the guns, and broke from the charging pace at the moment that it was most important to have continued it. The brigade fell, then, unavoidably into some confusion; more especially as the pools of water in front of the enemy’s battery obliged some of the men to make a detour. In doing this many of them began to load and fire. The result was that in a very brief space all order had disappeared. After a short interval of time, however, the scattered groups, finding themselves within reach of the guns, charged home as if with one mind, bayoneted the gunners, and for a moment held them!

But only for a moment. As the smoke cleared away, the Sikhs, noticing the small number of the men who had made that desperate rush, rallied; and, reinforced by infantry from the rear, recovered the battery; then, aided by their cavalry, drove back the brigade almost to the point which it occupied at the beginning of the action.

Colin Campbell, all this time, was with the left (Hoggan’s brigade). That brigade, facing, as I have said, the long gap between the left of the right division of the Sikh army, commanded by Atar Singh, and the right of the centre division, with which was Sher Singh, had, pushing on without meeting with opposition, penetrated the gap, and, wheeling to the right, had placed itself on the flank of the Sikh centre. This position,

however, was not so advantageous as it would at a first glance seem to be; for, whilst the right of the Sikh centre, wheeling in an incredibly short space of time, opposed a firm front to the British brigade, the entire right division, breaking from the opposition offered to their advance by the cavalry of Thackwell and the guns of Brind, wheeled to their left and fell on the rear and the left flank of Campbell. The latter, then, soon found himself engaged in front, flank, and rear – his sole chance of success resting on the courage and discipline of his men. The faith which Colin Campbell ever possessed in the British soldier was proved on this occasion to be well founded, for never did men deserve better of their country than, “during that mortal struggle, and on that strange day of stern vicissitudes,” did the gallant 61st.134

Leaving Campbell thus making head against considerable odds, I must proceed with the reader to the British right. There Gilbert had to encounter difficulties not less great than those which the other divisional leader had encountered. He, too, had to storm batteries, supported by infantry, and covered by jungle, in his front; and, what was worse, when he was deeply engaged with the enemy, he had to see his flanks uncovered – the left by the defeat of Pennycuick’s brigade, the right by the repulse of the cavalry, presently to be related. Nor had his own front attack been entirely successful. The left regiment of his right brigade, the 56th Native Infantry, after making head with great gallantry against superior numbers, and losing eight officers and three hundred and twenty-two men killed and wounded, had been forced back. The Sikhs, availing themselves of the gap thus produced, had separated the two brigades the one from the other, and these found themselves now, like Hoggan’s brigade on the left, assailed, each on its own account,

on front, rear, and flanks In this crisis, when everything seemed to frown on the British army, the behaviour of the Bengal Horse Artillery was superb. Splendid as is the record of that noble regiment, it may be confidently asserted that never did it render more valuable, more efficacious service to its country, never did it tend more to save a rash and headstrong general from the defeat he deserved, than on that memorable 13th January. The battery of Dawes attached to Gilbert’s division was, at the crisis I have described, of special service. “In spite of jungle and every difficulty,” records Durand, “whenever, in a moment of peril, he was most needed, Dawes was sure to be at hand; his fire boxed the compass before evening, and Gilbert felt and handsomely acknowledged the merit and the valour of Dawes and his gunners.”135

I have stated that whilst Gilbert’s left had been uncovered by the defeat of Pennycuick’s brigade, and his centre broken by the crushing in of the 56th Native Infantry, his right had been exposed by the repulse of the British cavalry. It happened in this wise.

The cavalry on the right was commanded by Brigadier Pope, an officer in infirm health. It included a portion of the 9th Lancers, the 14th Light Dragoons, the 1st and 6th Light Cavalry. “Either by some order or misapprehension of an order,”136 this brigade was brought into a position in front of Christie’s horse artillery – on the right of Gilbert’s division – thus interfering with the fire of his guns and otherwise hampering it. Before Pope could rectify his mistake, a body of the enemy’s horsemen, suddenly emerging from the jungle, charged his brigade, and one of them singling out Pope, cut him across the head with a tulwar. The brigade, taken by surprise, had halted, waiting for orders. In consequence of the

severe wound of the commander, no orders came, and the brigade, left to itself, and threatened by another body of horsemen, dashed, panic-stricken, to the rear, rushing over and upsetting guns, gunners, and gun-wagons in their headlong rout. The Gurchuras, whose inferior numbers did not justify this scare, pursued their flying enemy closely, dashed amongst the guns, cut down Major Christie, completely taken by surprise, and many gunners with him, captured all the guns of Christie’s troop and two of Huish’s, and would have penetrated to the general staff but for the gallantry of the 9th Lancers. These rallied behind the guns and checked the body of Gurcharas. A few of the latter, however, did advance to within a short distance from the Commander-in-Chief – so near, indeed, that his escort of cavalry prepared to charge. They were, however, dispersed by a few rounds of grape.

Up to this point the battle had gone badly for the British. We have seen the left brigade of the left division fighting for dear life, surrounded on three sides; the right brigade of the same division driven back almost to its starting point; the two brigades of the right division separated from each other, and each surrounded; the cavalry and horse artillery, which should have covered the extreme right, defeated, and six guns captured. Lord Gough must have been very sensible of the critical state of affairs when he ordered up Penny’s reserve to replace Pennycuick’s brigade. But all order had disappeared; the several regiments, it might in some cases be said the several groups of each regiment, were fighting for themselves, and Penny’s brigade, sent to reinforce Campbell, somehow found itself attached to Gilbert’s division.

Gough had now to depend mainly upon his infantry; and the stout men who composed that infantry did not fail him. On the right the pertinacity and the high courage of the 29th Foot and the 2nd Europeans (now 104th Regiment) gradually wore down the enemy; on the left, Campbell, repulsing every

attack, succeeded at last in forcing the Sikhs to give ground. On both flanks these successes were followed by a final charge, and the British cheer, sounding exulting even over the roar of artillery and the rattle of musketry, borne by the breeze to the ears of the Commander-in-Chief, was the first announcement to that gallant soldier that he might cease his anxiety, for that the day, if not won, was saved.