|

Find Environmental Information |

About Us |

Volunteer |

Site Map

|

Nick Lutz

Fall 2000

If you can stand the heat, summer in North Carolina is a beautiful time. For many, nothing is more rewarding or enjoyable than an evening outside working in the yard, playing a game or just relaxing with a cold drink. Unfortunately these pleasant times can be easily tarnished by the appearance of an uninvited guest, the mosquito. A trip out to the tomato patch quickly turns into a frantic swatting session followed by hours of itching and scratching.

|

Through my experience as a local mosquito control officer I have found that many people believe swarms of biting mosquitoes to be simply an unpleasant fact of summer. People are often amazed to discover that many of the mosquitoes that drive them indoors were born and raised in their very own yard. They are unaware that a few simple actions , such as removing unnecessary water from around their homes, could greatly reduce their numbers. While I must stress that an effective mosquito control program requires the cooperative effort of individuals and all their neighbors, combined with local and state government, a great starting point is personal awareness and knowledge. This article will focus on the Asian Tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus, a species of mosquito relatively new to North Carolina (1). I am focusing on this species because it tends to generate a large portion of public complaints and is one whose unique habits and characteristics tie its local population levels very closely with human activity (2). This means that individual mosquito control practices can have a significant impact on its population. Also, although so far it is only a problem because of its bite, it is a species that may prove to be a significant disease vector (3). |

Figure 1. Asian Tiger Mosquito. |

Figure 2. Adult Asian Tiger mosquito. |

To understand why mosquitoes are a problem, how they spread disease and how they can be controlled, it is first important to have a general understanding of their biology, life cycle and habits. Mosquitoes are relatively small, long-legged, two-winged insects belonging to the Order Diptera and the Family Culicidae (4). There are approximately 165 species of mosquito in America and approximately 56 species in North Carolina (5). A. Life HistoryMosquitoes have four distinct stages of life, which consist of egg, larva, pupa, and adult (33). The first three stages occur in water with the adult stage consisting of a freeflying insect that feeds on man, other animals or the juice of plants. B. EggsMosquitoes generally lay their eggs directly on the water or the just above the water line on damp soil or vegetation. The eggs of the Asian Tiger mosquito are laid on the sides of containers or tree holes just above the water level. When the water rises the eggs can hatch. The eggs of Asian Tiger mosquitoes and many other mosquito species can survive long periods of drying before the necessary flooding occurs. |

C. LarvaeThe larvae of all mosquitoes live in water. Depending on species, this will consist of permanent ponds and marshes, temporary flood waters such as ditches, low lying areas, or woodland pools, and water contained in treeholes, leaves of plants or artificial containers. Mosquito larvae can live in almost any water except flowing streams, and the open water of lakes and seas. While mosquito larvae get their food from the water most must come to the surface to breathe. The larval period consists of four developmental instars, or intermediate growth forms, which require from 4 days to 2 weeks to complete. Rate of development depends on factors such as water temperature and food supply. The colder the water the slower the rate of development. At the end of each instar the larva sheds its skin or molts. After its fourth molt a pupa is produced. D. PupaeAs with larvae, the pupae always require an aquatic environment. Pupae do not feed but for most species must come to the surface for air. Depending on water temperature and species this stage lasts from one day to several weeks. At the end of the pupal stage its skin splits open and the adult works its way out to the surface of the water and is soon ready to fly away. |

Figure 3. Mosquito Life Stages. |

An equal number of males and females are produced from eggs. Males generally reach adulthood first and in some species remain in the area in order to mate with females soon after their emergence. Asian Tiger Mosquitoes will often mate near the host when the female has come to obtain a blood meal (34).

Only females feed on blood. Most species require a blood meal before they lay fertile eggs. While only one mating will fertilize a female's lifetime supply of eggs she generally requires a blood meal for every batch of eggs she lays. The cycle of feeding, laying eggs and feeding again can be repeated many times in the life of one mosquito.

The life span of mosquitoes is unclear. Some species tend to live for one or two months while species that hibernate can live for up to six months or more.

Mosquito species demonstrate varying preferences in their choice of sources for blood meals. Some species prefer to feed on birds while others may prefer domestic animals and others prefer man. These preferences tend to be exclusive but not always. This means that a species that generally feeds on birds may accept a human host when the opportunity presents itself. Asian Tiger mosquitoes tend to prefer to feed on mammals, such as man or domestic animals but will feed on birds if no other host is available (35). The practice of obtaining many blood meals over the course of a lifetime combined with the potential practice of feeding on different classes and species of hosts helps explain how diseases can be transferred from one species of host to another.

The time of day mosquitoes feed also varies. Some species feed only during the day while others feed during the early morning and evening and others at night (6). Asian Tiger mosquitoes characteristically feed in the afternoon and occasionally in the morning (36).

Populations of the Asian Tiger mosquito first became established and were detected in Harris County, Texas in 1985 (7). Since then known infestations have been reported as far east as Florida and Georgia, north to Maryland and Delaware (9), and as far west as Chicago, Minnesota and Nebraska (8)

Figure 4. Distribution Map.

Source: Moore and Mitchell (1997) (13)

The Asian Tiger mosquito is known as a "container breeder" due to its practice of depositing its eggs in small pockets of contained water rather than swamps, marshes, or water-holding ditches, which are used by many mosquito species. It has been speculated that the Asian Tiger mosquito originated as a forest species that deposited its eggs in water-holding tree holes and leaf axils. Over time the Asian Tiger mosquito has adapted to the presence of humans and their tendency to provide an abundance of water-holding containers. This relationship has created a prosperous environment for the Asian Tiger mosquito where now a large portion of the population is produced in containers provided by humans.

The Asian Tiger mosquito will deposit eggs in almost any water-holding container in urban, suburban, rural and forested areas. The primary habitats of larvae are artificial containers such as flowerpots, cans, buckets, ornamental ponds, birdbaths, old tires, cemetery vases, and clogged rain gutters. Asian Tiger mosquitoes also still utilize natural containers such as tree holes, bamboo stumps, and leaf axils. As long as water remains in these containers long enough to complete their larval and pupae stages Asian Tiger mosquitoes will use these items to successfully reproduce (9, 10).

The Asian Tiger mosquito as its name suggests originates from the continent of Asia. There its range extends from New Guinea, westward to Madagascar, and northward through India, Pakistan and China to about the latitude of Seoul, Korea and Northern Japan (9).

Evidence suggests that Asian Tiger mosquitoes arrived in America from northern Asia via shipments of used truck tires containing eggs and or larvae (11). In Asia the used tires are often stored out of doors where they are allowed to accumulate rainwater. This creates an environment suitable for females to lay eggs. The tires are then shipped to various locations in America where they are once again left outside and allowed to accumulate rainwater. The mosquito eggs hatch and the young mosquitoes develop and emerge into their new American environment.

The flight range of the adult Asian Tiger mosquito is limited to a distance of 100-300 yards and they have not been observed to fly in strong winds (12, 13). It seems likely that the rapid spread of Asian Tiger mosquitoes has been aided by the distribution of used tires containing eggs across state lines and across the country (9). Once the new immigrants reach adulthood at a tire dump they will soon begin laying eggs in already present domestic tires. When these tires are shipped to various locations they deliver with them the mosquitoes they carry. This theory was supported by Moore and Mitchell, (13) who during the early period of Asian Tiger mosquito dispersal demonstrated a relationship between the appearance of Asian Tiger mosquitoes and the proximity of interstate highways and tire dumps.

Another method of transport relates to flower vases placed at cemetery gravesites (15). These vases are often used by the Asian Tiger mosquito for egg-laying. When the flowers die the vases are often reused, possibly at another cemetery. When the eggs develop the mosquitoes are once again released into a new environment.

The exact implications of the introduction of Asian Tiger Mosquitoes still remain unclear. It has shown itself to be an aggressive daytime biter, being most active in early morning and late afternoon (12). Generally it is the species that provokes the majority of mosquito complaints in areas where it occurs (2,16). Crans describes the Asian Tiger mosquito as "more aggressive than the Yellow Fever Mosquito, seeks hosts over a broader range of human activity, and has a bite that results in considerably more irritation" (17).

Viruses that are carried by mosquitoes are called arborviruses (arthropod-borne viruses). Most arborviruses occur in wild animals; most commonly birds and small mammals. In North Carolina eastern equine encephalitis (EEE) and LaCrosse encephalitis are the two most common types of arborviruses (18). West Nile Virus (WNV) is also an arborvirus that has recently been identified in several eastern states. WNV may potentially spread to North Carolina in the near future (19).

Generally arborviruses are spread from animal to animal or bird to bird by mosquito bites. Occasionally an infected mosquito will bite a person or domestic animal and pass the virus on to them (19). Several of the Asian Tiger mosquito's habits and characteristics have raised concerns within the scientific community regarding its potential as a disease vector within the United States. O'Meara et al. says, "North American strains of A. albopictus show a high degree of vector competence (ability to carry and transmit a virus) to several important arborviruses. The ability of A. albopictus to occupy a wide variety of habitats further enhances its chances of being a vector species." (3)

In the lab, vector competence studies show the Asian Tiger mosquito to be a competent vector of many arborviruses including EEE, dengue, Japanese encephalitis, West Nile and yellow fever viruses. In the real world, from field samples collected around the United States, only two viruses of public health importance have been isolated from ATM. EEE has been isolated from Asian Tiger mosquitoes on only one occasion in Polk County, Florida 1991 (21) and Cache Valley virus was isolated from a pool in Jasper County, IL (20).

The Asian Tiger mosquito has demonstrated itself to be an efficient transmitter of dengue fever in tropical areas of the Orient (17). Although dengue fever has been largely eliminated from the continental US since the 1940's it still occurs in the Caribbean fairly commonly. The threat of reintroduction by a traveler carrying the disease is an ongoing possibility (16). Once reintroduced the Asian Tiger mosquito could possibly aid in the disease's spread. To date the presence of Asian Tiger mosquitoes has not caused an increase in the number of dengue fever cases in the US.

The Asian Tiger mosquito has also shown the potential to transmit Dirofilaria immitis (canine heartworm) in the lab (22). However, another study suggested that North Carolina's strains of Asian Tiger mosquitoes demonstrated little potential as vectors of canine heartworm (23).

The Asian Tiger mosquito is not a transmitter of malaria. Malaria is spread by a different genus known as Anopheles (23). Although mosquitoes that potentially carry malaria do exist in North Carolina, disease transmission is rarely seen in the United States.

In summary the Asian Tiger mosquito has the potential to carry and transmit many dangerous arborviruses. This, combined with its opportunistic feeding habits, increases the possibility that it will do so. Despite its potential public health impact, according to Moore and Mitchell, "in terms of its role as an arborvirus vector, evidence is lacking to incriminate A. albopictus as the vector in even a single case of human disease in the United States." (24)

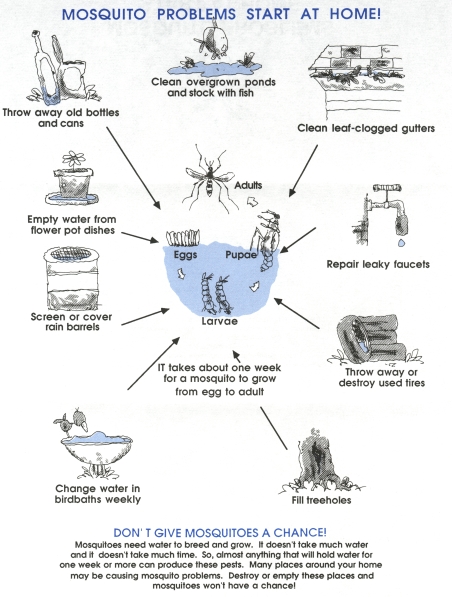

As stated earlier Asian Tiger mosquitoes are container breeders. Eliminating any and all water holding devices is a good way of reducing the potential for mosquito infestations. Because this is not always possible or feasible other methods of control can be utilized.

Eliminating mosquito-producing habitats includes removing all unnecessary water-holding containers and frequently changing the water in others (every 5 to 7 days). To help control all mosquito species, filling low areas and potholes with soil or draining water-holding low areas is recommended.

Figure 5. Eliminating Mosquito Habitats.

Source: NCDENR info

pamphlet (32)

If habitat removal is not feasible or desirable (such as a garden pool) other methods are possible. Biological control implies the destruction of larvae by predators or pathogens.

At the moment the best method of biological control is the addition of a larval-eating fish. Several species, including the mosquito fish Gambusia affinis and the guppy Poecilia reticulata, have demonstrated themselves to be very effective. In my experience I have never found a water body that contained a healthy population of small fish that also contained high numbers of larvae.

Bacillus thuringiensis israeliensis (Bti) is a bacterial compound that effectively controls mosquito larvae. It is sold commercially under many trademark names such as Bactimos, Teknar, and Vectobac in various forms such as liquids, granules, and briquettes. After being consumed by larvae, the bacteria release toxins that cause paralysis of the midgut and death within about a day. The microorganisms released into the environment do not self-perpetuate, so re-application is required. This larvicide is very selective and does not harm fish other aquatic organisms, plants, wildlife, pets or humans.

Bti is the only larvicide used by my mosquito control program in the Town of Chapel Hill. It has proven to be very effective with no undesirable side effects. Duration of effectiveness is one to two days depending on type of application. Briquettes (donuts) can be reasonably purchased at stores such as Lowe's or Home Depot and are slow-release formulas effective up to a month. Always read and follow manufacturer's instructions (25).

Nontoxic insect growth-regulating hormone is another larvicide used by mosquito control agencies. Brand name Altosid in granular form, it is spread by hand or using a seed spreader and functions by preventing larvae from growing to adulthood (26).

A final method sometimes used to control larvae is a monomolecular surface film applied to waters containing larvae. This alcohol-based, biodegradable film creates an impermeable layer on the surface of the water that prevents larvae and pupae from reaching the surface to breath, resulting in suffocation (26).

Adulticiding involves spraying chemicals into the air by either a truck with a sprayer or airplane to kill adult mosquitoes. This method provides only temporary control as mosquitoes migrate back into sprayed areas from unsprayed areas. Also larvae and pupae are not affected by spraying and will therefore continue to emerge and repopulate a sprayed area (25).

One obvious way to avoid mosquitoes is to stay indoors during periods when mosquitoes are most active, such as early morning and evening. If this is not possible, stay away from areas that are shaded, humid and calm. Mosquitoes bite less frequently in open, sunny areas with a little wind. Long pants and sleeves also deter mosquitoes and light-colored clothes make you less attractive to them (37).

Some personal protection from mosquitoes can be achieved through the use of insect repellents. DEET (N, N-diethyl-meta-toluamide) is the most effective repellent ingredient. Many products are available that contain from 5% to 95% DEET. Good Housekeeping conducted a product test and found that repellents containing 10-15% DEET to be very effective (38).

Morris and Day suggest that although DEET is an effective repellant, high concentrations make you feel unpleasantly oily and can melt plastic, watch crystals and paint finishes. They go on to say that some people are allergic to DEET and infants and children are more sensitive to it than adults. To minimize adverse reactions use repellant sparingly, avoid DEET concentrations greater than 50%, avoid applying repellant to portions of children's hands that may come into contact with eyes and mouth and wash repellant off skin after coming indoors (37).

If you wish to avoid DEET all together, Good House Keeping tested another product, Avon Skin-So-Soft Bug Guard plus sunblock, which contained no DEET, and found it to be very effective (38). Morris and Day suggest this as a good product for children, but advised that it is not effective for all people and will need to be reapplied more frequently (37).

Installing and maintaining tight-fitting window screens and doors will help keep mosquitoes out of your home (27). Citronella candles are often used to repel mosquitoes from an area out of doors. These work best when there is little air movement to disperse the chemical too quickly.

The Mosquito Magnet is a new device on the market. It functions by mimicking warm-blooded mammals by emitting a plume of heat and carbon dioxide and moisture. Mosquitoes locate their prey by utilizing sensors that detect heat and carbon dioxide. Mosquitoes are attracted to the device where they are vacuumed in and held in a trapping device where they dehydrate and die. According to the manufacturer one device will control mosquitoes within an acre of land (28). At present the cost of approximately $1,000 per unit is prohibitive but this device may prove very effective in certain circumstances.

Electric bug zappers are not effective in reducing mosquito populations. Although they do kill lots of insects, only a small portion of them are mosquitoes. They are more likely to kill beneficial insects and the light they emit attracts more mosquitoes to your yard than if you don't have one (37). Electronic mosquito repellers that emit high frequency sound to repel mosquitoes have not been shown to be effective (38).

Claims that certain plants such as the citrosa plant Pelargonium citrosum will repel mosquitoes are not supported by scientifically based test results (39). Bats and birds such as purple martins do consume mosquitoes as part of their regular diet. Erecting nesting boxes for these natural predators near your home may attract them to the area but their feeding activity is not sufficiently selective to cause noticeable reductions in mosquito numbers (37).

The exact implications of the Asian Tiger Mosquito's introduction to America remains to be seen. William Hawley describes the Asian Tiger Mosquito as "an ecological generalist capable of rapid evolution and, with the aid of man, speedy colonization of new habitats" (40). In the thirteen or so years since it was identified in America it has managed to spread over about one quarter of the country. How far it will continue to spread is unclear. In its homeland and elsewhere it is a major vector for several arborviruses. So far in Americait has not been responsible for the transmission of any human disease. What is clear is that the Asian Tiger Mosquito is highly adapted to an environment with man and a climate like ours in North Carolina.

The best way to control mosquitoes, especially Asian Tiger mosquitoes, is to remove larval habitats. This is done by eliminating unneeded containers and by frequently emptying the water from other containers, such as birdbaths and pet watering dishes. If the water cannot be removed, stocking with larvae-eating fish or treating it with Bti will serve to eliminate most larvae. By getting your neighbors involved as well as your local mosquito control agency it is possible to take back your yard during the summer months. Although the mosquito can never be eliminated it is certainly possible to minimize its impact on your life.

NC DENR, Public Health Pest Management, Mosquitoes Information Pamphlet

C. G. Moore, C. J. Mitchell (1997) "Aedes albopictus in the United States: Ten-Year Presence and Public Health Implications." Emerging Infectious Diseases, July-Sept 1997, 3(3).

The Why Files, Mosquito Bytes

D. B. Francy, C. G. Moore, D. A. Eliason (1990) "Past, Present and Future of Aedes Albopictus in the United States." J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 6: 127-132, 128.

North Carolina Public Health Pest Management,

Mosquitoes: General Information, page 2.

www.deh.enr.state.nc.us/phpm/pages/Mosquitoes.htm

G. F. O'Meara, A. D. Gettman, L. F. Evans, G. A. Curtis (1993) "The Spread of Aedes albopictus in Florida." American Entomologist, Fall 1993: 163-171, 171.

H.D. Pratt, C. G. Moore (1993) "Mosquitoes of Public Health Importance And Their Control." US Department of Health and Human Services, page 13.

Brunswick County, North Carolina:

Operation Services, Mosquito Control, page 1.

http://www.co.brunswick.nc.us/os5.asp

D. Springer, T. Wuithiranyagool (1986) "The discovery and distribution of Aedes albopictus in Harris County, Texas." J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 2: 217-219, 217.

Pratt and Moore (1993), page 23.

W. J. Crans (No date)

"The Asian Tiger Mosquito in New Jersey."

Rutgers Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet # FS845, The New Jersey

Mosquito Control Association, Inc., New Jersey Agricultural Experiment

Station Publication No. H-40101-01-95, page 1 of 3.

http://www-rci.rutgers.edu/~insects/tiger.htm

R. Novak (1992)

"The asian tiger mosquito, Aedes albopictus."

Wing Beats 3(3):5, page 1.

http://www.rci.rutgers.edu/~insects/sp8.htm

O'Meara, G.F. (1997)

"The Asian Tiger Mosquito in Florida."

Document ENY-632, Cooperative Extension Service,

Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida,

page 1 of 5.

http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/BODY_MG339

Novak (1992), page 2.

North Carolina Public Health Pest Management (2001)

"Biological Data on 25 Common Species of Mosquito Found in

Coastal North Carolina", page 1 of 2.

http://www.deh.enr.state.nc.us/phpm/pages/html/biological_data.html

C. G. Moore, C. J. Mitchell (1997)

"Aedes albopictus in

the United States: Ten-Year Presence and Public Health Implications."

Emerging Infectious Diseases, July-Sept 1997, 3(3), figure 1,

page 2 of 8.

www.cdc.gov/ncidod/eid/vol3no3/moore.htm

G. F. O'Meara, A. D. Gettman, L. F. Evans, G. A. Curtis, (1993) "The Spread of Aedes albopictus in Florida." American Entomologist, Fall 1993: 163-171, 165.

G. F. O'Meara (1997)

"The Asian Tiger Mosquito in Florida."

Document ENY-632, Cooperative Extension Service,

Institute of Food and Agricultural Sciences, University of Florida,

page 4 of 5.

http://edis.ifas.ufl.edu/BODY_MG339

W. J. Crans (No date)

"The Asian Tiger Mosquito in New Jersey."

Rutgers Cooperative Extension Fact Sheet # FS845,

The New Jersey Mosquito Control Association, Inc.,

New Jersey Agricultural Experiment Station Publication No. H-40101-01-95,

page 2 of 3.

http://www-rci.rutgers.edu/~insects/tiger.htm

NC Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Environmental Health, Public Health Pest Management Section (No date) "Mosquito Viruses... Some Facts." Information Pamphlet.

NC Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Environmental Health, Public Health Pest Management Section (No date) "West Nile Virus: Frequently Asked Questions." Information Pamphlet.

Moore and Mitchell (1997), page 4.

Mitchell et al (1992) "Isolation of Eastern Equine Encephalitis Virus from Aedes albopictus in Florida." Science 257: 526-527, 527.

E. Konishi (1989) "Susceptibility of Aedes albopictus and Culex tritaeniorhynchus Collected in Miki City, Japan to Dirofilaria immitis." Entomology Society of America 26(5): 420-424, 423.

C. S. Apperson, B. Engber, J. F. Levine (1989) "Relative Suitability of Aedes albopictus and Aedes Aegypti in North Carolina to Support Development of Dirofilaria immitis." J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 5(3):377-382, 383.

Pratt and Moore (1993), page 31.

Moore and Mitchell (1997), page 7.

Pratt and Moore (1993), pp 58-71.

Brunswick County, pp 2 and 3.

Pratt and Moore (1993), pp 72-74.

Mosquito Magnet by American Biophysics Corp.

http://www.mosquitomagnet.com/

ENT/rsc-6 (No date)

"Mosquito Control Around The Home and in Communities."

http://www.ces.edu/depts/ent/notes/Urban/mosqcon.htm

NC Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Environmental Health, Public Health Pest Management Section (No date) "Asian Tiger Mosquitoes... Some Facts." Information Pamphlet.

NC Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Environmental Health, Public Health Pest Management Section, "Mosquitoes... Some Facts." Information Pamphlet.

NC Department of Environment and Natural Resources, Division of Environmental Health, Public Health Pest Management Section (No date) "Mosquito Problems Start At Home!" Information Pamphlet.

Pratt and Moore (1993), pp 13-19.

W. A. Hawley (1988) "The Biology of Aedes Albopictus, Review Article." J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 4(supp. 1):1-39, 25.

Hawley (1988), page 23.

Hawley (1988), page 22.

J. F. Day, C. D. Morris (1993) "Avoiding and Repelling Mosquitoes and Other Biting Nasties, A Florida Mosquito Control Factsheet." Florida Medical Entomology Laboratory, University of Florida, March 1993.

Good Housekeeping (2000) "The Buzz on Bug Repellents, Good Housekeeping Institute Report." Good Housekeeping, August 2000, page 67.

B. M. Matsuda et al (1996) "Essential oil analysis and field evaluation of the citrosa plant Pelargonium citrosum as a repellant against populations of Aedes mosquitoes." J. Am. Mosq. Control Assoc. 12(1):69-74, 74.

Hawley (1988), page 30.

At the time he wrote this, Nick Lutz was the mosquito control officer for Orange County and a student at North Carolina Central University.

Thanks to Carol B. Rawleigh, copy editor.

"God made all the creatures and gave them our love and our fear,

To give sign, we and they are his children, one family here."

- Robert Browning, Saul, 1855.

Help us improve this page! Please share your comments, questions and suggestions.

http://ecoaccess.org/info/wildlife/pubs/asiantigermosquitoes.html

Last update:

2002/07/08 13:22 GMT-4

Send Feedback@ ~ About Us ~ Volunteer ~ Site Map

Site Credits: Content and Design ~ (Open Source) Free Software ~ Benefactors

EcoAccess helps you find and share useful environmental information online.

Web Site Release 5.0.2 (2003-05-08) Copyright © 1998 - 2003 EcoAccess