|

Find Environmental Information |

About Us |

Volunteer |

Site Map

|

Stacey Isaac

Spring 2001

Most of us can quickly come up with a list of ways that we as humans are destroying the natural environment. The items on our list often involve things like rainforest destruction and overpopulation; phenomena that we have little direct control over. However, the issue of invasive species strikes a little closer to home, maybe even as close as your front yard. Invasive species are responsible for significant ecosystem destruction all over the world. This article first outlines the global problem then it focuses on Chinese privet as an invasive species that is widely used for landscaping in the Triangle area.

The United States Department of the Interior defines "exotic species" as taxa that occur "in a given place as a result of direct or indirect, deliberate or accidental actions by humans." The word "taxa" simply refers to a class of organisms. "Invasive Species" are taxa outside of their native ranges (i.e. exotic species) that threaten the survival or reproduction of native plants or animals or threaten to reduce biological diversity (1).

The problem of invasive species is of worldwide proportion. Environmentalists say that exotic plant species in Mozambique put pressure on vital wetlands exacerbating floods that killed hundreds of people (2). In the US many experts now agree that invasive species are the second-most important threat to native species in this country. (Habitat destruction is viewed as the leading threat (3).)

Surveys have shown that gardening is the most popular outdoor activity in North America (4). Many people see their gardens as their source of exercise, accomplishment and simply as their link to the natural world. However, as innocent as this pastime may seem, it has led to one of the largest threats to natural plant species. While gardeners are not the only ones responsible for species introduction, they have been introducing exotic plants to this country for centuries. Invasive species are spreading so rapidly that "the unique differences of regional plant communities are blurring" (3). Conservative estimates claim that 2,000 alien plant species have established themselves in the United States. Of this number, experts feel that some 350 species should be considered as serious or dangerous invaders.

Invasive plants have been calculated as having infested 100 million acres in the US. These plants are believed to be spreading at the rate of 14 percent a year. They consume 4,600 acres of wildlife habitat a day and currently severely infest at least 1.5 million acres of national park land (5). According to a government report, "Invasive Plants: Changing the Landscape of America," introduced species now comprise between 8 to 47 % of the total flora of most states (6).

Every species, whether it is a bacterium, a mammal or a plant, has a specific part of the world where it has existed for thousands of years. Over time, natural forces and physical phenomena like climate, soil conditions, availability of moisture, incidence of fire and interactions among species have directed the distribution of organisms in nature. The species native to North America are generally considered to be those that occurred on the continent prior to European settlement (7).

The Nature Conservancy has divided the United States into 63 "ecoregions" based on climate and geology. About 8 of these ecoregions occur in the southeastern part of the country. Generally, any plant existing outside these 8 ecoregions are considered to be "exotic" to the southeastern US. Other terms that are synonymous with "exotic" are "non-native," "alien," "foreign," "introduced", and "non-indigenous".

"Invasive species" refers both to organisms brought from other continents as well as organisms moved from one locality in the US to another (7). It is important to remember that not all non-native species become invasive. Indeed, some organisms do not even survive in the location to which they have been introduced. However, in cases where the organism is able to survive, its survival often leads to its becoming naturalized in the new area. If the organism displays rapid growth and spreads easily in the new location, establishing itself over large areas, then it is not only considered exotic, but also invasive.

It is worth noting also that not all exotic species should be considered harmful. After all, corn, wheat and oats form the basis of the agricultural industry and supply a large proportion of the diet of the US. These exotic plants also generate huge amounts of revenue as export products (7). In addition, most exotic species tend to develop into invasives in climates similar to where they evolved, often at or near the same latitude (8).

With respect to exotic plants, the term "weed" is very popular. A weed is basically a plant that is considered to be "out of place." Classification as a "weed" lies totally in the eye of the beholder. Weeds can be either a native or a non-native plant. In some cases, invasive exotic plants are referred to as "natural area weeds."

The term "noxious weed" also has a very specific meaning. "Noxious" is a legal designation that is used specifically for plant species that have been determined to be major pests of agricultural ecosystems. The law actually mandates these plants to certain restrictions and they are regulated by the US Department of Agriculture. "Noxious Weed Boards" can designate plants as "noxious" at the state or county level. Though noxious weeds achieve that status through their harmful effects on agriculture, they are often also harmful to natural areas (9).

Invasive plants tend to have certain characteristics that give them the competitive advantage over native species. These include strong vegetative growth; for example, they may spread easily by rhizomes or suckers. They may also produce an abundance of seeds, have a high seed germination rate, produce long-lived seeds or rapidly mature to sexual reproduction (7). Another good clue that an exotic plant has invasive potential is the ability of the plant to spread by multiple methods, e.g. both asexual and sexual mechanisms (8). Whatever their methods of successful growth and reproduction, these plants overwhelm natural vegetation.

Another important contributor to the success of "invasives" is the fact that they are introduced to an area that is void of their natural predators and competitors. Thus, there is no natural control or check on growth and reproduction of these species. As an ecosystem evolves, natural interrelationships develop among the organisms and their natural environment. If a plant did not evolve in the given area such relationships, especially the competitive, host-pest, and predation relationships in this case, do not exist. Hence, the plant proliferates unhindered.

Invaders reduce the amount of light, water, nutrients, and, space available to native species. They can also change hydrological patterns, soil chemistry, moisture holding capacity, erodibility, and fire regimes (7). Some exotics are able to hybridize with native plant relatives. The results of such a situation are unnatural and potentially unfavorable changes to the plant's genetic pool. Other exotic plants act as reservoirs for plant pathogens. These pathogens can infect other plants, including native species and desirable ornamental plants.

Exotic plants may even contain toxins that are lethal to specific organisms. Invasive plants are also known to disrupt plant-animal associations such as pollination, seed dispersal and host-plant relationships. They can replace nutritious native plant foods with lower quality sources. Invasives can also increase erosion along riverbanks, shorelines and roadsides. Certain aquatic plant species have clogged lakes and waterways, altering and weakening these ecosystems. These same plants have often disrupted water treatment and supply facilities (10).

The financial costs incurred because of exotics are difficult to estimate. However, federal estimates are that in general invasive species cost the country 123 billion dollars every year (11). Also, about half of all species designated as threatened or endangered are in competition with or are preyed on by non-native species (12). As native plant species decline, the animals that depend on them for food are also at risk. Species that have very specific diets are at greatest risk. Thus some of the costs involved in protecting and conserving these native species are actually incurred because of invasive species. The 2002 Department of the Interior budget for National Parks includes a total of 49.5 million dollars for the National Resource Challenge, which involves the management of non-native or invasive species. This figure was larger than the 2001 figure by 20 million dollars. Over 2 million dollars of this increase is attributable to the control of invasive species (5).

In Guam the brown tree snake was introduced from New Guinea via military aircraft during World War II (13). This one species is responsible for having eliminated 10 out of the 13 native bird species, 6 of 12 native lizard species and 2 of the islands 3 bat species (12). The snake has inflicted over 200 harmful bites on people. It has caused over 1,200 power outages by intruding into electronic equipment or climbing on power lines. The Interior Department is spending 4.5 million dollars every year to prevent the spread of this snake from Guam (14).

In California, a recent arrival, the glassy-winged sharpshooter is an invasive insect that carries the plant pathogen, Xylella fastidiosa. The bacterium causes a plant disease that has cost the state 40 million dollars in damages to its grape crop. The costs are even higher when the effects on related industries like the raisin, wine and related tourist industries are considered. In fact, altogether, a 35 billion annual cost has been calculated (12).

With respect to plants, purple loosestrife, Lythrum salicaria, was introduced from Europe as an ornamental plant during the early 1800s. This plant now invades the wetlands of 48 states, costing 45 million dollars a year in control and other indirect costs. This species out-competes 44 native plant species and places wildlife that depend on these native plants at risk (6). The plant can produce 2.7 million seeds per plant every year and it spreads across about 480,000 additional hectares of wetlands each year (12).

The issue of invasive species is a relatively new area of concern. There is still a lot of controversy, even among experts, as to which plants are truly invasive and which are not (8). Some plants are easier to class as invasive than others. Kudzu is one example that there is no dispute over: it is definitely considered invasive. Kudzu is native to Asia, however the plant is now common in the southeast U.S and is found as far north as Pennsylvania . It is extremely common in the Triangle area. A little more ambiguity exists when it comes to classifying plants like Butterfly Bush (Buddleja davidii). This plant is native to China and Japan, but is now grown in this area for the high fragrance and nectar of it blossoms (15). In fact, Will Cook regards this plant as "the number one butterfly magnet" for central North Carolina. Some experts say it is not a problem in this area, while others feel that is has serious potential as an invasive species.

Chinese privet (Ligustrum sinense) is a plant that experts agree is causing damage as an invasive species in the Triangle. The Department of Agriculture regards the plant as one of the 14 species "with the potential to adversely affect management objectives" of North Carolina's National Forests (16, 17).

While botanists may be extremely concerned about the effects of Chinese privet, most local homeowners are unaware of the problems that this plant is causing. Some greenhouses and nurseries in the area actually supply this plant to local gardeners. A telephone survey of greenhouses and plant shops in the Triangle area revealed that many did have Chinese privet available for purchase at about fifteen dollars for a three-gallon pot. None of these shops advised purchasers on the invasive nature of the plant. Indeed, some shop owners were unaware of any deleterious effects of the plant. Brian Stubbs of a local greenhouse stated that the plant is very popular among buyers in the spring and summer. Most shops reported a general preference for the variegated version of privet. This form of the plant, according to Stubbs, is semi-sterile and only grows 5 to 6 feet (18). However, some customers prefer to pay the same price to receive the invasive form of the plant.

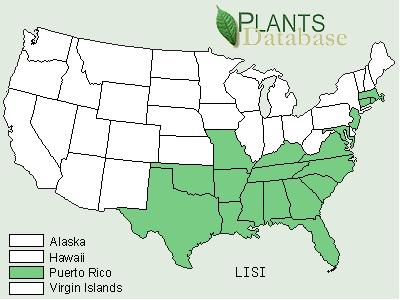

Chinese Privet was introduced to the US from China in 1852 for use as an ornamental shrub. The plant may have started to escape cultivation as early as the 1930s in Louisiana. It can now be found from Florida to the southern parts of New England. It stretches as far west as eastern Kansas, Oklahoma and Texas (19).

Figure 1. Plant Distribution by State. Source: USDA, NRCS, PLANTS Database (20)

Chinese privet often occurs along fences, stream banks and forest margins. It tends to form very dense stands at forest edges where it out-competes all other species, to be the only plant species in some cases. Gardeners use the plant mainly as a hedge. It is usually grown as a mass of plants, but sometimes an individual plant is grown. It produces a profusion of small white flowers (19).

The plant is very successful because of its effective reproductive mechanisms. Chinese privet reproduces both asexually and sexually. Huge numbers of seeds are produced and then spread by birds, especially songbirds and bobwhite quail. The seed is enclosed in a berry that birds feed on. They later discharge the seeds and so aid in dispersal of the plant. Plants used in landscaping provide a source of seeds for invading disturbed areas nearby. Disturbed areas can be natural, e.g. a tree fall or erosion in a forest, or artificial, e.g. abandoned farmland. The plant flowers from March to July and its fruits ripen from September to November. The fruits' persistence through winter (21) aids in the great success of the species. The plant can also propagate itself vegetatively from root suckers.

Chinese privet is a shrub with a height of 5 to 12 feet, but can grow to the size of a small tree of up to about 30 feet in height (19). It is a member of the olive family (22). Chinese privet has an extensive, but shallow root system. The plant branches abundantly and its branches arch down. The leaves are evergreen to semi-deciduous and elliptical in shape. Leaf blade dimensions are about 1 inch wide and two inches long. The two leaves at each node are arranged opposite to each other. Nodes are usually less than an inch apart along the stem. Chinese privet can be distinguished from other less invasive privets by the fine hairs (trichomes) on its twigs and underside of its leaves. The plant's white flowers occur in clusters. These clusters are normally cone-shaped and are produced in abundance. Each flower has four petals. Their odor is not pleasant. Certain parts of the flower eventually develop into a blue-black berry (19). The berry is very fleshy, but also contains a hard seed and is about a quarter inch in diameter (22).

Figure 2. Chinese Privet in bloom. Source: University of Florida, Center for Aquatic and Invasive Plants (23)

Chinese privet is versatile, able to survive a wide range of habitats, soil and light conditions. However, the plant thrives in wet damp conditions, loves mesic soils and abundant sunlight. As a result it is common around old homesites, low woodlands, bottomlands, streamsides and forest margins.

Chinese privet is harmful not only to ecosystems, but to humans as well. Ingestion of the plant's berries can lead to death in humans. The toxic berry causes abdominal pain, nausea, vomiting, diarrhea, headache, weakness and cold, clammy skin (24). The unpleasant odor of the flowers can cause respiratory irritation in areas where the plant is abundant (19).

Dense stands of Chinese privet may habor the tick Ixodes scapularis Say. This organism is a suspected vector of Lyme disease in the southern US. Chinese privet may also act as a host plant for the weevil Ochyromera ligsutri (25).

Chinese privet is very popular in landscaping because of its attractive white flowers, dark green foliage, resistance to most insects, dust and air pollution, and general hardiness (21).

Privet is also useful as windbreaks in reducing erosion. The fact that the fruits remain intact on the plant for a long time suggests that wildlife do not care for it. However, birds do consume some of the fruit. The plants provide habitat for wildlife in some cases (21). Privet foliage seems to be an important source of food for deer in northwestern Georgia. Stromayer et al found that cutting privet so that deer can reach it may be a sustainable and inexpensive way of maintaining deer forage availability.

Chinese privet tends to dominate the shrub layer of any habitat that it invades. It changes the natural species composition of the ecosystem by choking out native plant species. Privet shades out all herbaceous plants. In North Carolina thousands of acres of land have been invaded by this plant (22). It has particularly affected the bottomland and riparian habitats of the Nantahala and Pisgah National Forests in North Carolina (16).

Schweinitz's Sunflower (Helianthus schweinitzii) is endemic to the piedmont of the Carolinas. Only 10 populations are known to exist in North Carolina and 6 in South Carolina. The populations in North Carolina exist in the counties of Union, Stanly, Cabarrus, Mecklenberg and Rowan. The populations that once existed in Stokes and Montgomery counties have been eradicated. Chinese privet is an aggressive competitor of this endangered plant (26). The two species thrive under similar environmental conditions and therefore occupy the same habitat. The aggressive nature of Chinese privet gives it the competitive edge over this native plant. Thus Chinese privet provides a serious threat to the remaining 10 populations of Schweinitz's Sunflower in North Carolina.

In the article "Designing Stormwater Wetlands for Small Watersheds" the North Carolina Cooperative Extension asks residents to avoid Chinese privet. The article warns of the potential of non-natives like Chinese privet to convert a diverse ecosystem into a monoculture. Residents are advised not to introduce this plant and to even remove it if it begins to establish itself early in the wetland's development.

It is recommended that homeowners in the Triangle not plant Chinese privet in their yards and gardens. In cases where the plant already exists, it should be removed. Several options are available for removal.

Simple removal by hand is adequate for smaller plants. The underground parts of the plant must be removed to avoid resprouting. Tools like the mattock may be useful in removal of underground parts (19). Mowing or cutting repeatedly will not eradicate this plant. Some sources say that this will only serve to control the spread while other sources say that it will actually enhance the plant's spread. These mechanical methods are only effective when privet numbers are still small and cutting should be done as close to the ground as possible. On a larger scale, e.g. in natural areas, heavy equipment may be used, but the disturbance that this will cause to the soil may make the area even more susceptible to subsequent invasion (19). Mechanical methods are particularly useful in very sensitive areas where herbicides cannot be used.

Herbicides present an alternative method of eradication that does not disturb the soil as much as mechanical methods. The disadvantages associated with herbicide use include possible laws that may restrict their use and possible damage to non-target species. However, glyphosate herbicides have been effective against actively growing privet. Johnny Randall, a leading authority on non-native plants, recommends Roundup ™ as the best glyphosate herbicide in combating Chinese privet (27). According to Randall this is the safest herbicide, and it is available at a reasonable cost from most plant shops and greenhouses.

The trunk of the plant should be cut and the concentrated herbicide applied directly to the cut surface. Randall prefers this method since it can be done anytime of year, except during periods of freezing. Also, the chemical stays in the root and is then translocated throughout the rest of plant and the herbicide is biodegradable. Other active ingredients that are effective are triclopyr and metsulfuron. A foliar application in the late summer is also recommended. Herbicide application should be done in late fall after most native plants have dropped their leaves or in early spring when most natives are at less risk because they are still dormant.

There are two main options in terms of herbicide application. The first, called basal-bark treatment involves applying the chemical to the base of the shrub. However, this was found to cause leaves to drop so quickly that the herbicide's effectiveness was reduced since the chemical was not transported to other parts of the plant. The second method is the cut-surface treatment, where the stem of the plant is cut near the base and the herbicide is applied directly to the cut surface. This was discussed above and is the preferred method. In either case resprouting may occur if the plant is not left undisturbed for about a year after treatment to allow for thorough translocation (19). Cutting holes at the top of the freshly felled stump allows for better absorption of the chemical by the plant.

Biological control has not proven to be a feasible option for the control of privet thus far. However, a foliage-feeding insect, Macrophya punctumalbum, that is native to Europe is a pest to privet. A fungal leaf spot Pseudocercospora ligustri harms the plant as well as a root crown bacteria Agrobacterium tume-faciens (19). Nectriella pironi is another pest-pathogen of Chinese privet and creates galls on the plant. The weevil O. ligsutri was mentioned earlier as a pest to this invasive plant. Further studies are needed to test the possible role of this weevil as a seed predator of Chinese privet in the control of the plant (25).

In California and Idaho sheep and cattle grazing has been used to control invasive plant species (28). Randall, who works with the North Carolina Botanical Gardens, says that they conducted brief experiments with goats in the Botanical Gardens. However, even though the goats loved privet, they were nonselective in their eating, therefore placing native species at risk. He suggests that the use of goats in the winter when invasive species tend to be the only green foliage has potential as a method of controlling Chinese privet in this area (27).

Fire has also been investigated as a means of exotic plant control since some native plants actually benefit from occasional burning. Although fire has been used to kill large stems of privet, resprouting after the burning eliminates fire as a very effective eradication method. However, the use of fire as a pretreatment for herbicide application has shown some success (19).

Brown and Pezeshki experimented with waterlogging as a tool in controlling Chinese privet in western Tenessee. However, their results showed that the plant is capable of withstanding both short- and long-term flooding, thus flooding is not likely to eradicate the species from bottomland stands (29).

Apart from eradicating the plant where it already exists certain preventative measures are also noteworthy. Chinese privet, like most invasive plant species, takes advantage of disturbance to natural areas. Therefore, activities such as unnecessary clearing of natural vegetation should be avoided. Gardeners are encouraged to become familiar enough with plants that they can recognize native species from invasive ones. There are resources such as universities, arboreta, local nature centers, plant societies, and offices of the department of agriculture that can assist residents in identifying invasive plants (7).

Residents should use plants that are native to the area or at least those that are not known to be invasive. As invasive plants exploit bare soil, it is important to replace an invasive plant with a native one; otherwise the invasive plant normally reinvades the vacant area. Cook recommends planting yaupon (Ilex vomitaria) or other native hollies like I. glabra instead of privet for those who want to attract the birds. Other native options also include Eastern red cedar (Juniperus virginiana), a native juniper that the birds love as well (30).

In addition to tending to their own gardens, residents can also get involved in invasive plant eradication at the community level. Residents can offer to assist in removal projects of these harmful plants and promote native alternatives. Concerns over invasive species should be discussed with nurseries and greenhouses. These suppliers of invasive plants need to be provided with information about the harmful effects of plants that they may be selling. Clearly, the public needs to be better informed on the threat posed by invasive species to native plants.

For a good set of definitions that are necessary in understanding the concept of invasive species, and examples of invasive plant species in the United States, see:

· Alien Plant Working Group (No date) "Weeds Gone Wild: Alien Plant Invaders of Natural Areas." Plant Conservation Alliance

· A. Schwarz (1999) "Plants to avoid." Invasive Exotic Plant Species of the Southeastern United States. (Chapel Hill, NC: North Carolina Botanical Garden). 5 pages.

The following sources are excellent for information on the magnitude of the invasive species problem. They give monetary costs associated with controlling and managing these species.

·

Alien Plant Working Group (No

date) "Weeds Gone Wild: Alien Plant Invaders of Natural Areas." Plant

Conservation Alliance (Internet: Plant Conservation Alliance).

http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/

·

ENN News (1998)

"Non-native weeds invading America's landscape." Environmental

News Network, Thursday, April 30, 1998.

http://www.enn.com/enn-news-archive/1998/04/043098/weeds_21787.asp

·

ENN News (1999) "BLM to

intensify war on weeds." Environmental News Network,

Thursday, April 8, 1999.

http://www.enn.com/enn-news-archive/1999/04/040899/weeds_2558.asp

·

Invasive species Fact sheet,

July 11, 2000.

http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/press/doiinvsp.htm

·

Center for Biological

Informatics of the US Geological Survey (2001) "The Nation's Biological

Information System." January 16, 2001.

http://www.invasivespecies.gov/.

For a range of specific invasive species and the problems that they have caused see:

·

Secretary of Transportation

(1999) "Policy statement on invasive alien species." US Department of

Transportation, April 22, 1999.

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/inv_dot.htm

·

Center for Biological

Informatics of the US Geological Survey (2001) "The Nation's Biological

Information System." January 16, 2001.

http://www.invasivespecies.gov/.

· ENN News (1999) "Alien species: A slow motion explosion." Environmental News Network, July 7, 1999.

A comprehensive and concise source on kudzu (a particularly notorious invasive weed) is:

·

C. Bergmann, J. M. Swearingen

(1997) "Kudzu." Plant Conservation Alliance, Alien Plant Working

Group.

http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/fact/pulo1.htm

Kudzu seems to be one of the best documented invasive plant species, so a simple internet search will reveal countless other sources if you want more.

A good article dealing with Butterfly bush (another potentially invasive plant) and its uses in NC is:

·

W. Cook (No date) "Some

Great Plants for Attracting Butterflies in Central North Carolina."

http://www.duke.edu/~cwcook/plants4leps.html

Again, more details on Butterfly bush can be found through simple Internet searches.

The two best sources for physical characteristics of Chinese privet were:

·

V. Boyce (No date)

"Invasive Alien Plant Species of Virginia - Chinese Privet (Ligustrum

sinense)." Virginia Native Plant Society. 1 page.

http://www.vnps.org/invasive/FSLIGUS.html

·

USDA, USGS (1997)

"Noxious Weeds of North America - Noxious Weed Guide" US

Department of Agriculture, US Geological Survey, December 29, 1997. 8

pages.

http://dogwood.itc.nrcs.usda.gov:90/weeds/firstdraft/ligustrum.html#top

(site no longer available as of June 2002)

For maps showing distribution of Chinese privet, the following is an excellent site:

·

NRCS, USDA (2001)

"Plants Profile." Natural Resource Conservation Service.

http://plants.usda.gov/cgi_bin/plant_profile.cgi?symbol=LISI

Another good site for characteristics of Chinese privet is:

·

D. A. Mikowski, W. Stein (No

date) "Ligustrum L. - privet." (Corvallis, Oregon: Pacific Northwest

Research Station). 9 pages.

www.wpsm.net/Ligustrum.pdf

The effects of Chinese privet on the ecosytems in North Carolina are well illustrated in:

·

USFWS (2001)

"Schweinitz's Sunflower." US Fish And Wildlife Service,

Division of Endangered Species - Species Accounts. 3 pages.

http://endangered.fws.gov/i/q/saq6o.html

·

V. Boyce (No date)

"Invasive Alien Plant Species of Virginia - Chinese Privet (Ligustrum

sinense)." Virginia Native Plant Society. 1 page.

http://www.vnps.org/invasive/FSLIGUS.html

·

USDA (1998) "Monitoring

& Evaluation Report FY 1998 - An Annual Look at Implementation and

Effectiveness of the Forest Plans." National Forests in North Carolina,

United States Department of Agriculture. 52 pages.

http://www.cs.unca.edu/nfsnc/nepa/fy98monitoringreport.pdf

1. A. Schwarz (1999) "Plants to avoid." Invasive

Exotic Plant Species of the Southeastern United States. (Chapel Hill, NC: North

Carolina Botanical Garden). 5 pages.

http://www.co.mecklenburg.nc.us/coeng/Recycle/invsve.pdf

2. No author (2001) "South Africa to Weed Out Invasive Plants." Planet Arc, February 8, 2001. 2 pages.

3. ENN News (1998) "Non-native weeds invading America's

landscape." Environmental News Network, April 30, 1998

(Internet).

http://www.enn.com/enn-news-archive/1998/04/043098/weeds_21787.asp

4. C. Clarke (2001) "Native plants." Environmental

News Network, February 9, 2001.

http://www.enn.com/enn-news-archive/2001/02/02092001/quiz_41880.asp

5. NPS (2001) National Parks - Departmental Highlights:

Preserving our National Parks.

http://www.doi.gov/budget/2002/02Hilites/toc.htm

6. ENN News (1999) "BLM to intensify war on weeds." Environmental

News Network, Thursday, April 8, 1999 (Internet).

http://www.enn.com/enn-news

archive/1999/04/040899/weeds_2558.asp

7. Alien Plant Working Group (No date) "Weeds Gone Wild:

Alien Plant Invaders of Natural Areas." Plant Conservation Alliance

(Internet: Plant Conservation Alliance).

http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/

8. McLean (2001) Personal communication, February, 2001 (Durham, NC).

9. Federal Noxious Weed Act: Sec. 2814. Management of

undesirable plants on Federal lands.

http://www.aphis.usda.gov/ppq/bats/fnwsbycat-e.html

10. USFWS (No date) "Threats from Invasive Species." US

Fish and Wildlife Service.

http://invasives.fws.gov/Index7.htm

11. US DOI (2000) "Invasive species Fact sheet." US

Department of the Interior, July 11, 2000.

http://www.nps.gov/plants/alien/press/doiinvsp.htm

12. Center for Biological Informatics of the US Geological

Survey (2001) "The Nation's Biological Information System." Last

Updated 01/16/01.

http://www.invasivespecies.gov/

13. Secretary of Transportation (1999) "Policy statement

on invasive alien species." US Department of Transportation, April 22,

1999.

http://www.fhwa.dot.gov/environment/inv_dot.htm

14. ENN News (1999) "Alien species: A slow motion

explosion." Environmental News Network, July 7, 1999

(Internet).

http://www.enn.com/enn-news-archive/1999/07/070799/pestbeatsfire_3747.asp

15. C. R. Artaud (1997) Tri-ology 36(3), edited by

N. C. Coile and W. N. Dixon.

http://doacs.state.fl.us/~pi/enpp/97-may-juneall.htm

16. USDA (1998) "Monitoring & Evaluation Report FY

1998 - An Annual Look at Implementation and Effectiveness of the Forest

Plans." National Forests in North Carolina, United States Department of

Agriculture. 52 pages.

http://www.cs.unca.edu/nfsnc/nepa/fy98monitoringreport.pdf

17. The other 13 species are tree-of-heaven, silk tree, oriental bittersweet, ground ivy, Japanese honeysuckle, Microstegium vimineum, Miscanthus sinensis, princess tree, Canada bluegrass, kudzu, multiflora rose, sheep sorrel and Japanese spirea.

18. B. Stubbs (2001) Personal communication, February 19, 2001 (Durham, NC).

19. USDA, USGS (1997) "Noxious Weeds of North America -

Noxious Weed Guide" US Department of Agriculture, US Geological Survey,

December 29, 1997. 8 pages.

http://dogwood.itc.nrcs.usda.gov:90/weeds/firstdraft/ligustrum.html#top

20. USDA (2000) "Ligustrum sinense Lour. - Chinese

privet." USDA - Plant Resources Conservation Service, December 6, 2000. 3

pages.

http://plants.usda.gov/plants/cgi_bin/plant_profile.cgi?symbol=LISI

21. D. A. Mikowski, W. Stein (No date) "Ligustrum L. -

privet." (Corvallis, Oregon: Pacific Northwest Research Station). 9 pages.

http://www.wpsm.net/Ligustrum.pdf

22. V. Boyce (No date) "Invasive Alien Plant Species of

Virginia - Chinese Privet (Ligustrum sinense)." Virginia Native

Plant Society. 1 page.

http://www.vnps.org/invasive/FSLIGUS.html

23. University of Florida, Center for Aquatic and Invasive

Plants (No date) "Ligustrum sinense / Chinese privet."

Aquatic, Wetland and Invasive Plant Particulars and Photographs (Gainesville,

FL: Univ of Florida).

http://aquat1.ifas.ufl.edu/ligsin.html

24. A. B. Russell (No date) "Poisonous Plants of North

Carolina." Department of Horticultural Science, North Carolina State

University (Raleigh, NC: NCSU). 3 pages.

http://www.ces.ncsu.edu/depts/hort/consumer/poison/Ligusja.htm

25. J. P. Cuda, M. C. Zeller (1998) "First Record of Ochyromera

Ligustri (Coleoptera: Curculionidae) from Chinese Privet In Florida." Florida

Entomologist, December 1998, 81(4):582.

http://www.fcla.edu/FlaEnt/fe81p582.htm

26. USFWS (2001) "Schweinitz's Sunflower." US

Fish And Wildlife Service, Division of Endangered Species - Species Accounts.

3 pages.

http://endangered.fws.gov/i/q/saq6o.html

27. J. Randall (2001) Personal communication (Durham, NC).

28. ENN News (1999) "Cattle graze for the

environment." Environmental News Network, Tuesday, March 30,

1999.

http://www.enn.com/enn-news-archive/1999/03/033099/graze_2378.asp

29. C. E. Brown, R. Pezeshki (2000) "A Study On

Waterlogging as a Potential Tool to Control Ligustrum Sinense

Populations in Western Tennessee." Wetlands 20:3, September

2000.

http://www.sws.org/wetlands/abstracts/volume20n3/BROWN.html

30. W. Cook (2001) "Some Great Plants for Attracting Birds

in Central North Carolina." January 10, 2001. 5 pages.

http://www.duke.edu/~cwcook/plants4birds.html

At the time she wrote this article, Stacey Isaac was a student at North Carolina Central University.

Thanks to Carol B. Rawleigh, copy editor.

"God made all the creatures and gave them our love and our fear,

To give sign, we and they are his children, one family here."

- Robert Browning, Saul, 1855.

Help us improve this page! Please share your comments, questions and suggestions.

http://ecoaccess.org/info/wildlife/pubs/chineseprivet.html

Last update:

2002/09/05 00:15 GMT-4

Send Feedback@ ~ About Us ~ Volunteer ~ Site Map

Site Credits: Content and Design ~ (Open Source) Free Software ~ Benefactors

EcoAccess helps you find and share useful environmental information online.

Web Site Release 5.0.2 (2003-05-08) Copyright © 1998 - 2003 EcoAccess