2019: Volume 11, Issue 1 - Table of Contents

Transitioning from Apps to "App"ortunities for Students:

Examining the Educational Value of App Production

Grace Y. Choi

University of Missouri

Abstract

Application (app) is a prominent technology that affects many people’s daily lives. Recently, apps have gone beyond fulfilling individuals’ personal needs to be used in a broader context: education. One educational area that can greatly benefit from apps is media literacy. By acquiring media literacy skills, students can become critical producers and consumers of media. Although there are in-depth discussions about media literacy education, apps are still new topics that need to be discussed further. Thus, to demonstrate apps’ educational potential, I created an educational Android app called The Adventure of Mia and Ed (Media). Using this project as a case study, this article examines the experience of app production and argues that app production should be incorporated in students’ education. The analysis indicates that app production process can increase students’ researching, analyzing, and networking skills. However, there are possible downsides to app production due to apps’ visual concentration, ethical issues, and expenses. These findings illustrate that with proper guidance, educators and researchers can utilize apps’ multifaceted strengths to elevate students’ learning experiences.

Introduction

Today, there is a new superhero that is recognized more than red-caped Superman fighting bald-headed evil Lex Luthor. The new superhero character is a red-feathered bird fighting bald-headed evil pigs called Angry Birds, and it has become the new household name because of the application (app). Mikael Hed, CEO of Rovio that created Angry Birds, announced that users downloaded the app over 1.7 billion times as of early 2013 (Dredge, 2013). Due to its popularity, Angry Birds has been made into animations, books, and merchandise to provide more entertainment to consumers. However, Angry Birds is not the only prevalent app as there are many different types of apps from social media to tools. According to Apple and Google, users downloaded 50 billion apps from Apple’s App Store while they downloaded 48 billion apps from Google Play as of early 2013 (Perez, 2013). Apps are high in demand, and although people can easily see how apps are expanding popular culture, apps were quickly put into practical use and were not limited to just popular culture themes. As people use apps on a daily basis, they are influencing different areas of people’s lives.

One area where apps are making a significant change is education. The New Media Consortium’s 2012 Horizon Report named apps as emerging technology that has profound potential to significantly impact K-12 teaching and learning (Johnson, Adams, & Cummins, 2012). Also, in various app stores, people can find various apps under the Education category where apps are specifically created for educational purposes. Phil Schiller, Apple’s SVP of Marketing, stated that there were 20,000 education and learning iPad apps alone in 2012 (Rao, 2012). Although apps are increasingly affiliated with education, it is uncertain what kinds of activities or lessons students are learning from these app innovations. Are students actively engaged in apps in schools or are they just using apps to satisfy their entertainment needs? The reality of app usage in classrooms is disappointing as American Institutes for Research found that out of 245 classrooms observed, only 39 percent of classrooms were using iPads, and 59 percent of apps downloaded on students’ devices were non-academic apps (Margolin et al., 2014). Not only are apps sparingly used in educational settings, but also students are not actively engaged with apps. It might be true that there are many existing educational apps that provide sufficient learning lessons to students; however, teachers are likely choosing apps for students, and they are not making choices about what apps they use in classrooms. Moreover, students are continuously playing a passive role as consumers and users of apps as a result of company’s mass production of apps. In order for this app technology to be truly educational, students and educators should explore another area of educational possibility within the world of app design – the act of actually thinking out and building an app. By doing so, they can transition from consumers to producers and learn media literacy skills, which is defined as “the ability to access, analyze, evaluate, and create media in a variety of forms” (Center for Media Literacy [CML], 2011, para. 3). Engaging in app production can lead to untapped educational potential in teaching students the art of app design. Therefore, in order to demonstrate this transition, I created an educational app called The Adventure of Mia and Ed, and using this experience as a case study, this article examines app production from an educational perspective.

More specifically, I created this app to fulfill two purposes. The first purpose was to demonstrate that a student, who does not have any computer coding skills and digital media production background, could engage in self-digital media production to create an app using multiple affordable resources. Once students learn how to successfully create apps, the gap between producers and consumers can begin to close, and anyone can create apps to express their unique voices. The second purpose was to examine the process of constructing an app to identify positive educational characteristics of app production. It is easy for people to focus on the final app to see what it can do; however, app production can be just as valuable as app developers are learning to construct their messages in a digital platform. Therefore, this project aims to examine app production as digital literacy education to see how students can actively engage with apps and what learning lessons are embedded within this app production.

Background

Application (app) refers to a downloadable computer program for handheld computer devices, such as mobile smartphones and tablets. Apps are divided into two platforms: Android and Apple. The platform of app mainly depends on if people have either an Android or Apple device. Once people get access to either Apple’s App Store or Google Play, they can browse through various apps using categories. As of 2015, there are 24 different categories in Apple’s App Store, and there are 30 categories in Google Play. Also, these apps can be divided into two types: informational and experiential. While informational apps are designed to give straight facts and information, experiential apps provide interactive experiences, such as games, to users (Bellman, Potter, Treleaven-Hassard, Robinson, & Varan, 2011). A commerce aspect is prominent within these two general types of apps. App users can frequently encounter “in game purchases” and shopping apps where they can easily encounter purchase options. Even for free apps, their content is not fully guaranteed to be free as “in app purchases” are necessary to access more content and advance features. It is easy for app users to make app purchases because their Apple and Google accounts are integrated in app stores. Thus, with a click of a button, app users can make a purchase. For younger app users, this can be problematic because they can carelessly and accidently make purchases. However, some apps are equipped with parental consents, which prevents younger app users from purchasing and accessing inappropriate materials. Even though some apps have these hidden features, it is undeniable that the app world as a whole has extensive content; hence, whether people need to find a local restaurant or to have fun, apps became a part of people’s lives to assist them in their personal needs.

Apps have gone beyond serving personal needs to be used for education. For example, many school leaders from various educational levels have realized the potential educational benefits of apps, and they are gradually adopting them in their institutions. For example, Dr. Rhett Allain, Associate Professor of Physics at Southeastern Louisiana University, utilized the Tracker video analysis to obtain data of bird flying motions in Angry Birds to demonstrate how he used velocity and accelerations to calculate the slingshot and the red bird’s sizes (Allain, 2010). Instead of using a general textbook example, he incorporated popular media as visual aids and primary resources to explain physics. Moreover, by describing his steps to students, Dr. Allian can teach them on obtaining their own data from the app to calculate different physic problems, which then the app becomes a personalized learning tool for students. Conceptualizing about science can be difficult because of many complex equations and theories to memorize from textbooks. Although teachers and students have historically used textbooks to access information and find educational examples, incorporating a popular entertainment, like apps, alongside textbooks can elevate learning by creating emotional interaction. Researchers found that users of pleasing aesthetics are likely to receive more satisfaction and pleasure (Rogers, Sharp, & Preece, 2011). Because apps, like Angry Birds, provide high quality graphics, engaging context, and opportunity to play, students can be more emotionally attach to participate in the curriculum.

App developers are also creating educational apps to be used in different classrooms. Simon Wood and Pablo Romero (2010) developed an iPhone app called Move Grapher, which helps students to learn about physics by using sensors on iPhones to translate students’ physical movements (walking, running, etc.) into kinematic graphs. By testing their app in the classroom, they found that the iPhone mobile device was a useful platform because it has a GPS service that can sense movements, its screen size was ideal to produce graphs, and the device had established popularity among students that increased the participation. In the testing stage, researchers found that most students were able to easily utilize and understand the app. The students’ experience with the app confirmed creators’ method to identify the iPhone mobile device’s strengths and constructed their app to take advantage of these strengths. Thus, understanding mobile devices’ characteristics is important to meet individual subject’s educational needs. App developers also integrate apps with other medium’s strengths. Israel, Marino, Basham, and Spivak (2013) conducted a participatory research where they observed 89 fifth graders designing paper prototypes of an educational app about circuits and electricity. By analyzing students’ designs, researchers found that all students designed their apps as games and incorporated visually appealing content. In addition, students’ game app designs were similar to foundational components found in video game designs, which suggest that video games are a significant influencing factor in educational apps (Israel, Marino, Basham, & Spivak, 2013).

App developers are also merging different media, such as radio and apps, to be used as an educational tool. Elisabeth Soep (2011) observed an after school program in California called Youth Radio that developed the Mobile Action Lab to help students to produce apps. They made various apps that include All Day Play, which is their radio station app that hosts independent artists and disc jockeys who are free from corporatization. She found that making an app encouraged students to think about community needs and social issues, such as thinking about how can an app decrease reckless spending and what messages need to be heard in the community? Also, she noticed that even after the program was over, students were inspired to produce apps on their own. This observation signifies that when students are guided to properly use technology in a team setting to discuss about designing an app, learning about coding, and rising of potential problem, such as sexting and cyberbullying, they can become self-directed learners to engage in app production. Moreover, because app technology has the ability to combine multiple media and content, students can have one-stop experience to become multimedia users.

Other professions are also using apps outside of educational settings. For example, Jessica Gosnell, a speech-language pathologist at Children’s Hospital Boston, used the “whiteboard” app as a communication assessment tool for evaluating patients, recording sessions, and creating task lists for patients, which have been useful and successful for both speech-language pathologist and patients (Dunham, 2001). Moreover, many speech-language pathologies found useful clinical apps from the Special Education section in the Apple’s App Store. This showed that apps that were originally created for an educational setting can be used outside of school contexts where other people can learn to customize their apps for their needs. Although there is limited literature on educational apps, these examples provide a background on how researchers, app developers, students, and other professions are incorporating apps into their lives to learn about their uses. Furthermore, these people’s positive experience with apps illustrate the importance of studying app technology as people can have various learning experiences, especially when it comes to media literacy education.

Theoretical Approaches

The essential focus of this article is media literacy education, and although it is still a developing concept, it has various deeply rooted theoretical approaches that can be acknowledged. First, media literacy can be traced back to the communication theorist Marshall McLuhan. In Understanding the Media, McLuhan (1964) argued that the medium, not the content in that medium, helps people to perceive and interact with the world. He goes on to emphasize that technology is important because media have different structures on how they influence and engage people. He illustrates this concept by providing examples of “cool” and “hot” media. “Hot” media, like radio and photography, does not need complete audience involvement because they mostly rely on one human sense and the information is straightforward; however, “cool” media, like television and cartoons, require active participation from audiences in which they need to organize and extract the meaning (McLuhan, 1964). As for apps, while they can be “hot” media as people are focused on using their functions, apps also can be “cool” media as people identify alternative uses of apps and make their own apps through app production. These engagements with both “hot” and “cool” media require people to be media literate and become active users of various technologies.

Whereas McLuhan emphasized the technological aspect of media, cultural theorist Stuart Hall examined the importance of examining the messages of media, which is a core aspect of media literacy. In “Encoding/Decoding,” Hall (1980) analyzed how media messages are produced and circulated. Messages are interpreted in various ways because audiences are not passive so they will analyze given messages. He acknowledges the importance of the production process because it encodes the messages, but he puts greater emphasis on the decoding part of message because that is where transferring of unintended messages can happen. Also, because connotative meanings of symbols and signs in media messages can represent different ideologies throughout cultures, the decoder should be careful not to assume that there is one universal meaning that applies to everyone (Hall, 1980). Hence, it is important for decoders to have the necessary skills to interpret messages, which can be learned through media literacy education.

In the digital age, a participatory culture encourages people to create media messages – the concept that is emphasized in digital literacy education. According to Henry Jenkins (2006), a participatory culture is defined as “a culture with relatively low barriers to artistic expression and civic engagement, strong support for creating and sharing creations, and some type of informal mentorship whereby experienced participants pass along knowledge to novices” (p. xi). As digital media technologies, such as apps, expand, the participatory culture has enabled average consumers to “archive, annotate, appropriate, and recirculate media content in powerful new ways” (Jenkins, 2006, p. 8). In order to do this, people need to have appropriate skills and knowledge to confidently use ever-changing media technologies to fulfill their goals. These acts also signify that people no longer just decode messages, but they can also be a part of the encoding process where they can construct messages. By doing so, they are critically thinking about media messages, which can increase their media literacy skills. Engaging in app production is a participatory culture, and students can learn more about apps while increasing their digital media production skills.

The Project: The Adventure of Mia and Ed

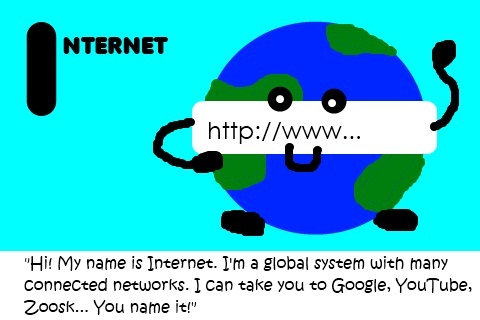

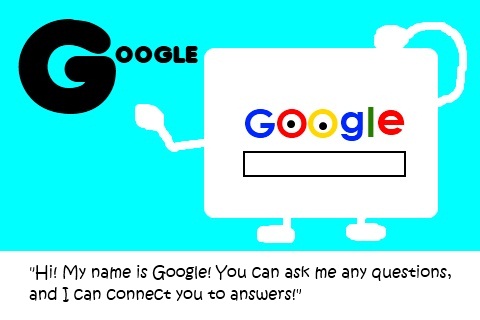

Applying theoretical framework of media literacy education, and in order to go beyond just being users of commercialized apps, I created an app, called The Adventure of Mia and Ed, to understand more about apps. The Adventures of Mia and Ed (Figure 1) is an Android app that includes a story and a quiz to teach younger students about various Internet related technologies and media. The story part of the app tells Mia and Ed characters’ adventures in the Digital Land. The adventure consisted of helping a laptop character named Lappy to defeat an evil virus named Y2K by learning various Internet and media related characters starting from A through Z (Figure 2). The quiz part will test students about what they learned. The goal of this app was to help children to familiarize with technologies and media as characters in the story so children can conceptualize technologies and media as more than just tools and think of them as “friends” who can provide learning opportunities. This is where the title of the app, The Adventure of Mia and Ed, comes from. When both names, Mia and Ed, are combined, the word “media” is formed. Thus, the story is not just about characters, but it is about a child, who reads this story, learning through the adventure of media.

The Adventure of Mia was a self-directed and a single person project that took about a month. The app production of The Adventure of Mia and Ed had different stages. First stage began with the story development. Because this app’s ideal audience is children, the story had to be easily understood. Hence, I applied a frequently used children’s storyline of going on an adventure into the app’s story. The story starts with two characters, Mia and Ed, who enter into the Digital Land by discovering a magical computer in their home. They discover a laptop character named Lappy who tells them the Digital Land is frozen by an evil virus named Y2K. They need to defeat Y2K by learning media characters starting from A through Z. Children will learn about characters and their functions. When they feel confident about knowing these characters, they can enter into Y2K’s quiz that asks five questions about random characters. When they pass the quiz, they save the Digital Land. Through this story, the goal of this app is to help a child to gain an informative knowledge and deeper understanding of Internet.

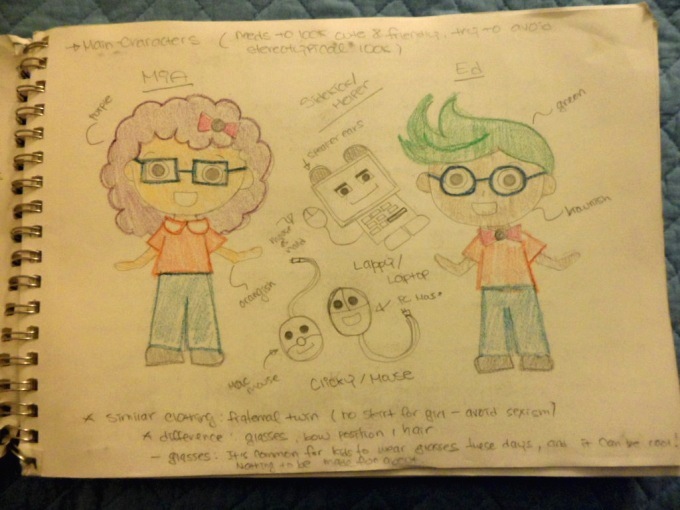

The designing process came after the story development. The design of the app was first roughly sketched out in a drawing book. In this drawing book, characters’ developments, the narrative, the title, fonts, explanations, and the app icon were created as rough drafts (Figure 3). Several screen frames of a smartphone and app icon’s templates were printed to draw possible story scenes and app icons. Because this app’s target audience is children, I emphasized on cute graphics and vibrant colors to increase the visual appeal. I then transformed rough sketches into digital sketches by Paint.NET computer program. There were few software options, such as Adobe Photoshop, Adobe Illustraror, Paint, ArtRage, and Paint.NET. However, I specifically chose Paint.NET because it is free software, has its own online community, and has more advanced functions than other basic programs. These factors are important because although Adobe software will result in highest quality, I want to suggest an efficient resource for those who will follow my methodology to produce their own apps. When the story and design stages were completed, I decided on the platform of the app. There were two choices: Apple and Android app. Android app was chosen for two reasons. First, the Android app can reach a wider audience than the Apple app. According to the 2012 Nielson Mobile Insights, within 49.7% of U.S. mobile owners who have smartphones, 48% have Android phones while 32.1% have Apple iPhone (Tippin, 2012). This statistic shows that it is better to target Android phone users because if this growth continues in the future, it can foreshadow the Google Play’s domination in apps that can expose the app to a greater number of people. Moreover, it is more effective to make an Android app because Google Play is available in many different affordable gadgets while Apple’s App Store is only available through Apple products.

Secondly, making an Android app is more affordable than an Apple app. In order to make an Android app, the developer needs to pay one time registration fee of twenty-five dollars. However, in order to make an Apple app, the developer needs to pay ninety-nine dollars yearly for the developer program and registration. Therefore, affordability and reachability were two main reasons that made The Adventure of Mia and Ed an Android app.

I constructed the Android app through a platform called Buzztouch website. Buzztouch is web-based free software that allows the user to design and manage the content of either Android or Apple app without coding (“About Buzztouch,” 2012). Learning computer codes can be complex and time consuming, thus, using this platform has helped to simplify the app making process. However, because this platform is still developing and has its own complex interface that uses limited plugins instead of codes, the user must need to take time to get used to the site and proactively ask questions in the forum. After creating the app in Buzztouch, I downloaded app codes to the Eclipse. Eclipse is free downloadable software where Android app developers insert app codes. App developers can fix their codes and run codes in the simulator where they can see their apps in the Android phone interface. After checking app codes, they were packaged into Android Application Package (APK) file. Subsequently, I created my app developer profile, accepted developer distribution agreement, paid registration fee, and uploaded APK file to the Google Play website. It took about 5 hours for the app to be found in the Google Play website and its app store.

Discussion

The first purpose of this project was to see if a person without computer coding and digital media production experience can create an app. It was achieved as I was able to produce The Adventure of Mia and Ed app at the end. The completion of this project signifies that app technology is not just about consumption or admiration, but it can be about a new opportunity to participate in a digital media world. While some students and educators, who have limited technology experience, might be hesitant to participate in app technology because it is an unfamiliar territory, with proper resources and motivations, they can participate in app production to create their unique apps. Although there is no certainty that they will produce the next Angry Birds app or anything close to that, app production revealed to be not an impossible task. Especially for students, who are full of creativity and constantly developing their skills, this can be an empowering process where they can get to see their ideas come into life. In addition to creating their own app, they can receive unique hands-on educational experience through app production.

App Production Process and Its Benefits

The second purpose of the project was to see if app production process has any educational value. It was discovered that there were various learning opportunities throughout different stages of app production. First, the planning stage of app production can enable students to learn about developing an idea. The planning process consists of designing and laying out details of app content, such as sketching scenes (Figure 4). In order to plan, students need to develop an idea for their app. Thinking about an idea for their apps is important because it can encourage students to research realistic problems. Especially when app production is framed as educational experience in class, educators can help students to think about purposes of their apps and if they can help to solve a problem. Although there are many apps that are created for entertainment purposes, there are other apps, such asFlashlight and Pill Identifier, which can be used to fulfill simple purposes. By knowing that app developers can influence people’s daily lives, students can be encouraged to research about society’s needs and envisage how their apps can support users in satisfying those needs. Moreover, they can bring their own cultural issues to the table. For example, there was an app called Filipino or Not (no longer available)? This app was a game app where users answer questions about Filipinos representations in media. By using this app, users can understand about Filipino culture and reflect on their assumptions based on what they saw on media. These examples illustrate that with proper guidance from educators, students can be intrinsically motivated to produce apps because they can choose personal topics, like learning about their cultures, so they can be self-fulfilled. Furthermore, students can be extrinsically motivated to produce apps because they can pick app topics that can positively impact the world.

After forming ideas for their app, students can learn to critically analyze their ideas because they are immersed in simulations. Simulation is defined as “the ability to interpret and construct dynamic models of real-world processes” (Jenkins, 2009, p. 41). In simulations, students rephrase their idea into various messages, create directions on where different components of apps will connect together, and test out their plan in the production. In the app production, simulations are when students are creating digital versions of their app images (Figure 5) and inserting codes into simulators in software. In simulations, students will often find that their plans for an app will not turn out to be what they expected. I had to scratch out many interactive components for The Adventure of Mia and Ed because it did not work out no matter how I repeatedly tried inserting codes into Buzztouch and Eclipse software. However, encountering with obstacles from experimentations gives students a chance to discover alternate answers. Because there are many possibilities in app production, students need to make many trial and error attempts to find answers that work and satisfy their goals. Although many students will be frustrated by this process, they will be motivated to fix problems because they are personally involved with this project as they have previously established important purposes to their apps. Thus, participating in simulations teaches students to be flexible because they have to continuously modify their models and learn to manipulate their data to test out different variables (Jenkins, 2009). Additionally, since everyone’s data is different due to their personalized apps, students need to fix their problems and create directions on their own. However, although they will have individualized app projects, since they are interacting in a same platform to modify codes, they can also collaborate with other students in their class to find answers together. By discussing about their experiences and methods in simulation, students can push each other to be critical of their work.

Another stage of app production that students can learn from is the story development stage, which can help to increase students’ writing skills. Especially story apps, like The Adventure of Mia and Ed, can help students to engage in creative writing because they are engaged in a storytelling process. One definition of story is described as “an audience’s understanding of the chronological development of the narrative” (Booth, 2009, p. 374). In order to develop a story, students need to create a structure of beginning, middle, and end, and they also need to identify how they will tell a story and what messages they will convey. This requires students to create some kind of a storyboard where they can practice writing their stories and lay out different components. Carefully planning out their stories is important because as app developers, students have become creators of media messages in which other people are in a position to analyze their content. Because they now have extra responsibility as media creators, they have to continuously write and constantly revise their stories so they can accurately and creatively translate their unique stories to messages, and messages to ideas.

Being able to participate in a storytelling process in app production is also important because it gives voices to students. Whether it is short, long, fictional, or non-fictional, the story is built upon a natural, organic, and authoritative narrative voice (Lambert, 2010). For example, when students decide to make a travel app about a trip to Europe, they are reexamining their experiences and narrating from their perspective. Even for creating a fantasy story app, students are involved in creative expression. Furthermore, when students are making a utility app like Flashlight, they are also creating their own storylines for users to follow to turn on the flashlight in a customized setting. Even though turning on a light using an app might sound like a simplistic task, different app developers can create their own steps for users to get to the light button. When students are telling their stories, they are also engaged in a creative process to design their stories. This is valuable because it gives students an opportunity to creatively express themselves through words, images, and sounds, which students can reflect upon their self-efficacy (Jenkins, 2009). By doing so, students can discover new insights about themselves that can build self-confidence through voicing their ideas. Hence, not only are they creating stories in apps for other people, they also are finding their own uniqueness through their stories. Students’ uniqueness is embedded in their apps, and they contribute to how each app can be distinctive from other apps.

The ability to express their uniqueness can be empowering to students because they tend to lack a voice, or the ability to affect change, in school. In most schools, their activities include following rules, listening to teachers, doing homework, and taking standardized exams. These activities create boundaries for students where they are limited by what they are given. Therefore, because students’ voices are suppressed in the traditional learning system, participating in app production can give a freedom to students so they can tell various stories using their unique voices.

When students have finalized their stories and ideas, they can learn to network with different levels of developers in the testing stage of app production. App technology is still developing with newer apps, and many people are trying to find easier ways to produce apps. In researching app resources, I found very few free platforms where apps can be produced. Also, in the process of creating app codes, there were many technical errors in Eclipse and Buzztouch that could not be fixed by an inexperienced student. Thus, because there are limited free resources and unpredictable technological challenges, students need to actively seek out information by networking with other app developers through forums and online communities. Especially for students, networking is essential as they are likely to lack technology experience and external resources. Networking can be a learning opportunity because it can help students to increase their communication skills and interact with various people. They need to able to clearly formulate their questions and thoughts into words so others, who are from various backgrounds, can easily understand to help them. These interactions with app developers can be also overwhelming as students can be inundated with information; thus, students need to analyze gathered knowledge to identify which resources are most useful. Networking is a crucial part to app production for those who are inexperienced, and it can help students to connect with various people. However, in the process, they need to become critical users to select information that specifically pertain to their needs.

Networking has another benefit, as it is also more than acquiring information and communicating with other people who have the same interests. Networking is about having the skills to effectively spread ideas and media products (Jenkins, 2009). Students do not just receive information from networking, but they also need to know how to give information back to the network. This can be done in various ways. When they have made some progress in their production process, students can help out other beginners who are new to app production. In addition, when students submit their apps to the app market at the completion of their app production, they are communicating with app reviewers and other developers who helped with and provided feedback for their apps. This can be seen by Buzztouch’s Facebook page where many app developers post links to their apps to showcase their products. Other Buzztouch users comment on them and praise them for their efforts. There are also other online communities, like MacRumors and AndroidForums, where students can interact with other users by introducing their apps and telling their journeys on making apps. By interacting with others through networking in various forums, students can gain skills to open up a discussion about their apps in their app production process.

Lastly, the overall app production process creates an appreciation for app technology. It is easy for people to take apps for granted because they are easily consumed and always accessible. However, by making their own apps, they can recognize the complexity of the app making process. For example, Angry Birds looks like a simple point and shoot game; however, it started its development in March 2009 with 10 people and was released to the public in December 2009 (Ridney, 2010). This example demonstrates that making an app takes many resources and efforts. By engaging in app production, students can understand complex steps to create an app. Completing these steps adds to celebration for those students who made an app, and they can reflect on their efforts to see how they overcame with different obstacles.

Educators and parents can also learn to appreciate the value of app technology by observing its educational effects on their students. This is necessary because according to the interviews conducted by Ito (2009), many parents and educators regard students’ time with new media as a “waste of time,” and they place many restrictions on students’ usage of new media at home and schools. However, because students can learn to analyze messages, develop their own messages, and connect with other people by engaging in an app production, adults can realize the importance of supporting their students’ engagements in this educational practice.

Potential Drawbacks to App Production

While app production has many educational benefits, there are also limitations to app production that cannot be overlooked. One downside to making an app is that students might be too focused on designs. When students are researching about other apps, they can see that most of popular apps are made with advanced visual presentations. These observations can add more pressure to students to produce equivalent graphics in their apps. However, they will find that creating high quality graphics require more advance skills using expensive tools, and their apps might look more simplistic than what they have originally planned. Although students can work on creating attractive visuals, which can help to increase their creativity and graphic skills, it can prevent students from working on other aspects of apps, such as encoding meaningful messages and providing practical functions in their apps. In educational context, because the main purpose their apps is more important than how pretty they are going to look, students need to be guided to prioritize their goals and not to be discouraged by high quality visuals in mainstream apps.

Additionally, focusing on visuals can discourage students from thinking about how their apps can trigger other human senses, such as hearing and touching. This is necessary because if students are contributing new ideas to apps, they should developing innovative ideas that are different from other apps that mainly focus on visual aspects. Critics can argue that apps already incorporate other senses like hearing and touching. Instead of continuously heightening app users’ visual sense, student app developers should find ways to go beyond visual technology so users can enhance their multi-senses. For example, researchers at the University of California at San Diego are working together with Samsung to create a component in televisions and cellphones that can release scents that match the content (Smalley, 2011). Although this development might not be practical for students’ projects due to their skills, students can work with other teams and researchers so they can engage in creating innovative ways to further current apps. This requires educators to partner with other organizations to connect their students with more experienced technicians. Through various collaborations, students can produce educational apps in which their users will be able to smell various flowers from all over the world without traveling, touch a range of fruits to feel different textual qualities, hear the sound of weather in addition to temperature indicated numbers, and exercise between classes guided by motion sensors in apps. Hence, it is important for students to go beyond repetitive design focus in existing apps and should be encouraged to think of new ideas.

Students should be also guided when they are making their apps because there are many ethical issues to consider. People have become more vulnerable, and they have less control over their information because new media technologies make it easier for anyone to capture and distribute information (Ess, 2009). Many apps require a user to create an account or sign up using Facebook, Twitter, or Google accounts. If students want to integrate social media into their apps, they should be responsible to protect their users from the danger of exposing their personal information. This means that they need to learn about Internet security and safety, and how they can incorporate that into their apps.

In addition, students need to beware of what content they are putting in their apps. Not only does this apply to circulating inappropriate content, but students should also be cautious of plagiarism, that is, taking other people’s content without permission. Therefore, as people’s vulnerability increases, distributors should have increased responsibility so they will not harm others (Ess, 2009). Because there are no ethical guidelines for apps, and students are creating their unique expressions as they communicate through apps, they might not realize that they are circulating inappropriate content or creating offensive apps. Hence, students should obtain guidance from either educators or experienced app developers so they are reflective on their choices when working with apps.

Going beyond apps, devices’ limitations should be considered because students cannot engage in app production in the first place unless they have devices. This limitation can lead to participation gap, which is defined as “the unequal access to the opportunities, experiences, skills, and knowledge that will prepare youths for full participation in the world of tomorrow” (Jenkins, 2009, p. xii). One factor that causes a participation gap is expenses. If students are producing their apps by themselves, they have to find a way to get these devices. If app production is incorporated in school curriculum, schools need to purchase devices, such as tablets, for students and educators. Although there are various options for device types, these devices’ costs might be unrealistic for both students and schools. As of 2015, cost of Apple products, likeiPads, range from $269 to $1,079. Non-Apple products, such as Samsung Galaxy Tabs, are not anyway cheaper as their costs are similar to Apple products. Especially for schools, because they cannot just get one device, purchasing multiple devices will result in a higher cost. For example, the Auburn school committee in Maine has approved to spend $200,000 for 285 iPad 2 tablets for kindergarteners to use apps for learning letters, reading books, and finger paintings (Aamoth, 2011). Although there is an option to decrease expenses by purchasing refurbished electronics from stores or getting sponsored from organizations, like Computer Recycling Center, by sacrificing the price, there will be unpredictability in quality that can cost more through tech supports. Furthermore, even if students and schools manage to get devices, they might need to purchase apps, other software, and fees. Hence, putting all necessary costs together, app production can be costly for students and schools who do not have extensive budgets. This means that there will be a divide between students who can and cannot participate in app production due to the affordability, which can create a separation in knowledge. Money should not restrict some students from receiving digital literacy education, but it is a realistic concern when it comes to providing an opportunity to engage in app production to students.

Conclusion

The overall purpose of this paper and project was to examine characteristics of app technology by specifically looking at app production and its educational potential. This examination was necessary because while apps are widely used, app production is not emphasized and its educational implications are not yet explored. This article identified some educational benefits in participating in app production. First, it is possible for a person without technical skills to make an app because there are platforms, such as Buzztouch, that can help with making an app. It does not only take skilled coders to create an app, but anyone can be self-directed to engage in app production. Also, students can acquire specific skills, such as researching, writing, and networking, as they are necessary for making an app. However, students need proper guidance when they are engaged in app production because there are a few considerations, such as visual concentration, expenses, and participation gap.

There were a few limitations to this project. First I had limited time and resources to build The Adventure of Mia and Ed, which prevented more professional finish to the app, such as high quality graphics and interactive components. For example, I had to cross out many plans from my original sketches, such as allowing students to insert their names on the screen, because I could not find the way to make it work. For other researchers, they can concentrate more on making apps that are comparable to top listed apps, to prove that ordinary students can produce professional quality apps.

The emphasis on app production should encourage people to see that apps are not just about entertainment or for personal needs, but they can be practical tools to enhance the current educational system. By using this project as a starting point, other researchers and scholars can implement app curricula in actual classrooms to observe students’ interaction with apps and gather their perspectives and establish criteria to measure educational value of apps and app production. Also, researchers and scholars can partner with non-profit organizations, such as App Camp for Girls, or university’s program, such as Massachusetts Institute of Technology’s Center for Mobile Learning, to strengthen their app curricula and impact a greater number of students. For critical and cultural studies scholars, they can continue to incorporate and analyze digital media production, and not just digital media products, to a create bridge between producers and observers. Digital media production is a significant part of studying media, and scholars from various academic and methodological backgrounds, in spite of their limited media production skills, should engage in production to understand diverse perspectives of studying media.

In the end, education can go beyond the traditional route, and it can be innovating through incorporating digital media technology. Hence, there needs to be more research on how apps can be utilized in education so various students can get their “app”ortunities. By doing so, little angry birds who are bored and frustrated by the current education can transition to become learning birds to successfully fly away to the new world.

Author Bio

Grace Y. Choi (Ph.D., University of Missouri) is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Humanities and Social Sciences at DigiPen Institute of Technology. Her research interests include digital literacy education, digital production, social media, media effects, and creativity, and her work is focused on making real-world impacts on education and culture.