Date: Tue, 9 Nov 2004 13:49:30 EST

The Effects of Compost Tea on Golf Course Greens:

Presidio Golf Course, San Francisco CA

Christa Conforti1, Marney Blair1, Kevin Hutchins2, and Jean Koch1

CConforti_at_presidiotrust.gov

1. Presidio Trust, San Francisco, California, USA

2. Arnold Palmer Golf Management Company, San Francisco, California, US=

A

Abstract

In an attempt to reduce the need for pesticides and improve the overall

health of turf and soil, the Presidio Golf Course conducted a field trial t=

o

evaluate the effects of compost tea applications on golf course greens unde=

r

real-world conditions. Greens were sprayed at a rate of one gallon of compo=

st tea per

1000 ft2 for twelve months. Applications occurred weekly during times of hi=

gh

disease pressure, and bi-weekly during times of moderate or low disease

pressure. Turf was evaluated for color, density, root depth, and disease an=

d weed

infestation. Soil was tested for carbon dioxide and oxygen level. Turf trea=

ted

with compost tea had longer root length, and less microdochium patch than

untreated turf. Treated turf did not differ from untreated turf in color, d=

ensity,

soil carbon dioxide, soil oxygen, or weed infestation. Compost tea has beco=

me

an integral part of the Presidio Golf Course pest management and the overal=

l

turf maintenance program. Further trials are needed to evaluate various

application rates and application methods to determine the full potential e=

ffects of

compost tea on golf course turf and soils.

Introduction

Pest management on golf courses has traditionally included regular pesticid=

e

applications, particularly on greens. Many of these pesticides have the

potential to harm wildlife, humans, or move into groundwater. Golf courses =

are under

increasing scrutiny and pressure to minimize the use of synthetic turf care=

chemicals (Balogh and Anderson 1992; Walker and Branham 1992). This pressur=

e

comes both from within the golf course industry and from environmental and=

community groups (Dinelli 2000; USGA 1996). Because of this, many golf cour=

se

managers are looking for effective alternatives to chemical pesticides and=

fertilizers. Compost tea, or aqueous extract of compost (Bess 2000), has be=

en used in

agriculture to suppress various fruit and vegetable diseases (Quarles 2001;=

Hoitink et al. 1997; Brinton 1995). Work with compost tea to suppress turf=

diseases and reduce fertilizer needs on golf courses is a relatively new en=

deavor

(Ingham 2001).

The aim of this field trial was to evaluate the effects of a twelve-month

compost tea regimen, under the conditions of a working San Francisco golf c=

ourse.

This trial was not intended to be narrowly focused, precisely controlled

study. Rather, it was intended to determine if the regular use of compost t=

ea was

feasible within an environmentally conscious golf course superintendentâ=

€™s turf

management program, and if this use would reduce the severity of the primar=

y

foliar turf diseases common to this course: microdochium patch (pathogen

Microdochium nivale) and anthracnose (pathogen Colletotrichum graminicola).=

The

trial also aimed to determine if the use of compost tea would increase soil=

microorganism and nutrient levels.

Materials and Methods

This trial was conducted from November 2000 through November 2001, at the

Presidio Golf Course in San Francisco California, on two creeping bentgrass=

(Agrostis spp.) greens. Varieties of bentgrass on both greens were SR1119, =

SR1020,

and SR1019. Both greens were sodded with this blend of bentgrass one year

prior to the beginning of the trial, and they were maintained at a mowing h=

eight

of between 0.125 and 0.18 inches. Both greens were subject to foot-traffic =

of

approximately 70,000 rounds of golf during the duration of the trial. Each=

green was divided in half for the purpose of the trial; one side received c=

ompost

tea applications while the remaining side received no compost tea. All othe=

r

maintenance practices including mowing, fertilizer applications, dew-remova=

l,

and soil aerification, were uniform across each green. No pesticide

applications occurred on these greens during this trial.

Compost and compost teas were made on-site. Compost was made from equal par=

ts

wood chips, grass clippings, and horse manure plus horse bedding. The recip=

e

for this compost blend was produced with the help of Woods End Lab, ME. Aft=

er

compost was made, biodynamic preparations (Pfeiffer 1984) were added to the=

compost windrows. Mature compost was taken from compost piles no less than =

four

months old that had previously been maintained at 135°F for three to f=

ive

days. Compost tea was brewed in a fifty-gallon Growing Solutions Microbrewe=

râ for

the first six months of the trial, and in a one-hundred-gallon Growing

Solutions System100â for the last six months. Before each brewing cycl=

e, water was

placed in the brewer and de-chlorinated by aerating the water for at least =

one

hour. Additives, such as molasses and a compost tea catalyst by Growing

Solutions (made of sea kelp, cane sugar, rock dust, and yeast) were added t=

o the

de-chlorinated water. Compost was then placed in the brewer baskets. One

five-gallon bucket of compost was used in the Microbrewerâ, and approx=

imately two

five-gallon buckets of compost were used in the System100â. Brewing o=

ccurred for

eighteen to twenty-four hours, respectively. The resulting compost tea was=

transferred to a spray rig and applied to the turf within four hours of bre=

wing

time. Quality testing of the compost and compost tea was performed quarterl=

y

during the trial. Testing was performed by Soil Foodweb, Corvallis OR.

The compost tea was applied through a Smith Co. Spray Star 1600 boom spraye=

r

with a fifteen-foot boom. Compost tea was mixed with de-chlorinated San

Francisco municipal water, and sprayed at a rate of 1-gallon compost tea/10=

00 ft2.

Applications occurred weekly during periods of high disease pressure (Novem=

ber

through March), and biweekly during moderate to low disease pressure (April=

through October). Applications generally occurred in the early morning befo=

re

7:30 am. Application methods alternated between (a) drench applications in =

which

the spray was watered in with five to ten minutes of irrigation following t=

he

application, and (b) foliar applications, in which the spray was left on th=

e

surface of the green.

Analytical Methods

Each experimental green was divided into quadrants (two treated with compos=

t

tea, two untreated) for the following evaluations:

Percentage turf affected by weeds and disease symptoms were recorded weekly=

for one randomly selected square foot per quadrant.

A subjective rating of turf color and turf density on a scale of 1-10 was

recorded weekly for one randomly selected square foot per quadrant.

Root depth was measured monthly by pulling a soil profile sample with a soi=

l

probe, to determine thatch and root depth (inches).

Soil CO2 level, and soil O2 level were measured monthly by placing a soil g=

as

meter approximately two inches deep into the soil beneath the turf.

For all turf and soil characteristics except disease occurrence, data was

graphed as time series plots of the mean value for each sample date, and an=

ANOVA

for each characteristic versus treatment and date was performed on data fro=

m

last ten months of the trial. For disease occurrence, data was graphed as t=

ime

series plots of the mean disease occurrence for each sample date within the=

time span of high disease pressure, and an ANOVA for disease occurrence ver=

sus

treatment and date was performed on data from time span of high disease

pressure.

Results

Root Depth

Figure 1 shows a time series plot of the root depth for treated and untreat=

ed

turf. During the first two months of the trial, root depth of turf treated=

with compost tea did not significantly differ from untreated turf (P=0.12=

0).

During the last ten months of the trial, turf treated with compost tea did =

root

significantly deeper than untreated turf (P=0.001). Mean root depths (n=

=4)

during the last ten months of the trial for treated and untreated turf were=

2.49,

and 1.89 inches, respectively.

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

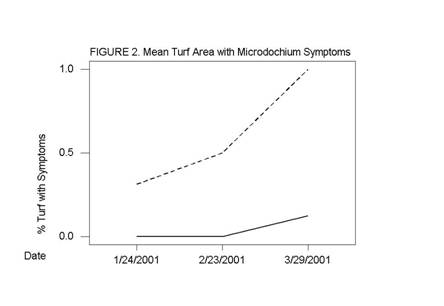

Microdochium Patch

Figure 2 shows a time series plot of the microdochium patch symptoms during=

times of highest microdochium disease pressure, for treated and untreated t=

urf.

During this time, turf treated with compost tea showed less microdochium

patch symptoms than untreated turf (P<0.001). Mean percent turf areas with=

microdochium symptoms (n=4) on treated and untreated turf were 0.042%, an=

d 0.604%,

respectively.

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

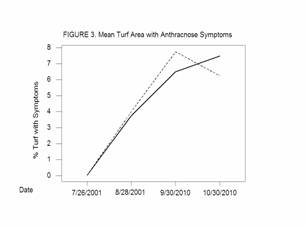

Anthracnose & Weeds

Figures 3 and 4 show time series plots of mean anthracnose damage (n=4) f=

or

times of high anthracnose disease pressure, and mean weed infestations (n=

=4)

throughout the trial. Turf treated with compost tea did not significantly d=

iffer

from untreated turf in terms of anthracnose symptoms (P=1.0) or weed

infestation (P=0.519).

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

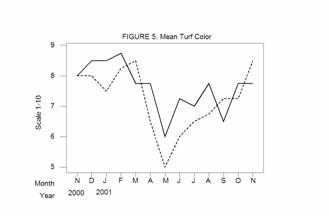

Turf Color & Turf Density

Figures 5 and 6 show time series plots of mean turf color (n=4) and mean =

turf

density (n=4) throughout the trial. Turf treated with compost tea did not=

significantly differ from untreated turf in color (P= 0.112) or density

(P=0.110).

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

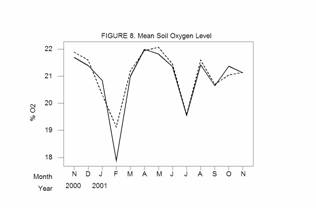

Soil CO2 & Soil O2

Figures 7 and 8 show time series plots of mean soil CO2 levels (n=4) and =

mean

soil O2 levels (n=4) at a soil depth of two inches. Turf treated with com=

post

tea did not significantly differ from untreated turf in soil CO2 (P= 0.25=

2)

or soil O2 levels (P= 0.584).

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

____ treated

_ _ _ untreated

Conclusions

The use of compost tea on golf course greens suppressed the severity of

microdochium patch although anthracnose was not affected. The difference in=

mean

root depth during the last ten months of the trial was 0.60 inches, or a 31=

.7%

increase. The difference in microdochium patch symptoms was 0.562%. While t=

hese

differences were small, they were significant within the context of a golf=

course green. On turf that is under the stress of a 0.125-inch mowing heigh=

t and

the foot-traffic of 70,000 rounds of golf per year, and under the foggy

conditions of San Francisco, both of these differences are substantial. Sin=

ce a

deeper root system allows turf to better withstand foot traffic and thresho=

lds

for turf diseases on golf greens are very low, these differences were

significant to the golf course superintendent.

Areas that warrant further study include increasing the compost tea

application rate or adjusting the application method to move the compost te=

a into the

soil profile, and adjusting the recipe of the compost and compost tea to

improve microbial aspects of the compost tea. Quality tests run during the =

trial

showed high bacterial levels and moderate fungal levels in the compost tea =

(data

not shown). Increasing the temperature during brewing, testing various

catalysts, or allowing the microbe populations in the compost to further ma=

ture and

stabilize might possibly improve the quality of the compost tea and influen=

ce

the results.

More study is needed to fully understand how to use compost tea to its

greatest benefit on golf course greens. However, due to the results of this=

trial,

and additional work done to improve the application protocol, compost tea h=

as

become an integral part of the pest management and general turf management=

program on all Presidio Golf Course greens.

References

Balogh, J.C., and J.L. Anderson. 1992. Environmental impacts of turfgrass

pesticides. p. 221-353. In J.C. Balogh and W.J. Walker (ed.) Golf Course

Management and Construction: Environmental Issues. Lewis Publishers, Chelse=

a, MI.

Bess, V.H. 2000. Understanding Compost Tea. BioCycle. 41(10):71-72.

Brinton, W., M. Droffner. 1995. The control of plant pathogenic fungi by us=

e

of compost teas. Biodynamics. 197:12-16.

Dinelli, Dan. 2000. IPM on Golf Courses. The IPM Practitioner, 22(8):1-8.

Hoitink, H. A. J., Stone, A. G., and Han, D. Y. 1997. Suppression of plant=

diseases by composts. HortScience. 32:184-187.

Ingham, E.R. 2001. The Compost Tea Brewing Manual, 2nd Ed. Soil Foodweb Inc=

.,

Corvallis, OR.

Pfeiffer, E. 1984. Using Biodynamic Compost Preperations and Sprays.

Biodynamic Farming and Gardening Association. San Francisco, CA.

Quarles, W. 2001. Compost tea for organic farming and gardening. The IPM

Practitioner. 23(9)1-8.

USGA. 1996. USGA 1996 Turfgrass and Environmental Research Summary The Unit=

ed

States Golf Association, Golf House, Far Hills, NJ.

Walker, W.J., and B.Branham. 1992. Environmental impacts of turfgrass

fertilization. P. 105-219. In J.C. Balogh and W.J. Walker (ed.) Golf Course=

Management and Construction: Environmental Issues. Lewis Publishers, Chelse=

a, MI.

Elaine R. Ingham

Soil Foodweb Inc., Corvallis, Oregon

Soil Foodweb Inc., Port Jefferson, New York

Soil Foodweb Institute, Lismore Australia

Soil Foodweb Institute Cambridge, New Zealand

Laboratorios de Soil Foodweb, Culiacan, Mexico

Soil Foodweb Inc., Jerome, Idaho

Soil Foodweb Inc., South Africa

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image002.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image004.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image006.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image008.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image010.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image012.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image014.jpg)

(image/jpeg attachment: clip_image016.jpg)